Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to systematically review the findings of publications addressing the epidemiology of anal HPV infection, anal intraepithelial neoplasia and anal cancer in women.

Data Sources

We conducted a systematic review among publications published from January 1, 1997 to September 30, 2013 in order to limit to publications from the combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) era. Three searches were performed of the National Library of Medicine PubMed database using the following search terms: “women and anal HPV”, “women anal intraepithelial neoplasia”, and “women and anal cancer.”

Study Eligibility Criteria

Publications were included in the review if they addressed any of the following outcomes: (1) prevalence, incidence, or clearance of anal HPV infection, (2) prevalence of anal cytological or histological neoplastic abnormalities, or (3) incidence or risk of anal cancer. Thirty-seven publications addressing anal HPV infection and anal cytology remained after applying selection criteria, and 23 anal cancer publications met the selection criteria.

Results

Among HIV-positive women, prevalence of HR-HPV in the anus was 16-85%. Among HIV-negative women, prevalence of anal HR-HPV infection ranged from 4 - 86%. The prevalence of anal HR- HPV in HIV-negative women with HPV-related pathology of the vulva, vagina and cervix compared with women with no known HPV-related pathology, varied from 23-86%, and 5-22%, respectively. Histologic anal HSIL (AIN 2+) was found in 3-26% of the women living with HIV, 0-9% among women with lower genital tract pathology, and 0-3% for women who are HIV-negative without known lower genital tract pathology. The incidence of anal cancer among HIV-infected women ranged from 3.9-30 per 100,000. Among women with a history of cervical cancer or CIN 3, the IR of anal cancer ranged from 0.8-63.8/100,000 person-years, and in the general population, the IRs ranged from 0.55-2.4/100,000 person-years.

Conclusions

This review provides evidence that anal HPV infection and dysplasia are common in women, especially in those who are HIV-positive or have a history of HPV-related lower genital tract pathology. The incidence of anal cancer continues to grow in all women, especially those living with HIV, despite the widespread use of cART.

Keywords: Anal Cancer, anal intraepithelial neoplasia, epidemiology, HPV, systematic review

Introduction

Squamous cell cancer of the anus (SCCA) incidence has been increasing over the past several decades, among women and men. Historically women have had a higher incidence of anal cancer than men, and recent publications have shown that the incidence rate for cancers of the anus, anal canal and anorectum in all ages and races of women has more than doubled, with an increase from 0.946 per 100,000 in 1975 to 1.827 per 100,000 in 2008.1 It is estimated that 3,000 cases of anal cancer related to HPV occur in women in the United States each year.

Recently, many epidemiologic studies have highlighted the increase in anal cancer of certain sub-populations of men; specifically, men who have sex with men and HIV-positive individuals have a significantly higher incidence of cancer compared to the general population.2 There have been fewer publications addressing the changing epidemiology of anal cancer among women, and these publications have demonstrated that the risk of anal cancer has significantly increased among HIV-positive women,3 with the incidence of anal cancer in HIV-positive women increasing from 0 between 1980 and 1989 to approximately 11 per 100,000 in the years between 1996 and 2004.4 Thus, SCCA, is a growing problem for women in the United States, especially those who are HIV-positive.

SCCA shares biologic similarities with cervical cancer, including detectable precancerous lesions and high-risk (HR) human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. HPV has been detected in 99% of cervical cancers and 80 to 90% of anal cancers, with HR HPV types 16 or 18 detected in about 70% of cervical and 80% of anal cancers.5 Thus, anal HPV infection, in conjunction with other yet to be determined factors, leads to the development of high-grade squamous anal intraepithelial lesion (AIN 2+), a likely precursor to anal cancer.6,7

As programmatic screening for cervical cancer with cytology has been associated with markedly decreased incidence and mortality of cervical cancer, anal cytology (from a Dacron swab inserted into the anal canal) has been evaluated as a screening method for anal neoplasia. Individuals with abnormal anal screening cytology are referred for a colposcopic evaluation of the anus called high resolution anoscopy (HRA) where the anal canal is examined with a colposcope after the application of 5% acetic acid and/or lugol solution and lesions are biopsied for histologic diagnosis. A growing body of literature has utilized screening of the anal canal using HRA and anal detection of HPV. However, the majority of literature evaluating the epidemiology of anal HPV infection, anal neoplasia and anal cancer has focused on HIV-positive men who have sex with men.

Objective

The aim of this paper is to systematically review and to summarize the findings of publications addressing the epidemiology of anal HPV infection, anal neoplasia and anal cancer in women.

Methods

We performed a systematic review for publications of anal HPV infection, anal histological and cytological abnormalities in women, and anal cancer in women published from January 1997 to September 30, 2013. Because the publications evaluating HPV-related disease were so heterogeneous (different methodologies for HPV testing, different types of publications, different types of cohorts), and because we wanted to include as many publications as possible to get a full perspective of the research that has been done to date, we conducted a systematic review rather than a meta-analysis. We confined the search to publications published after January 1, 1997 in order to limit the publications to the combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) era.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

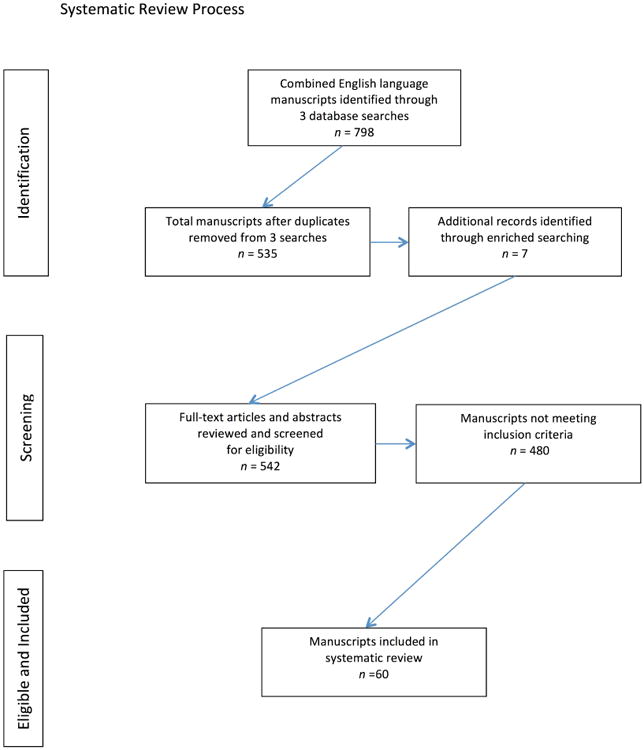

We performed three searches of the National Library of Medicine PubMed database using the following search terms: “women” and “anal HPV”, “women” and “anal intraepithelial neoplasia”, and “women” and “anal cancer”. The searches were limited to humans, published in English language with full text available during the time period specified. The searches produced a total of 798 manuscripts. After duplicate papers, review papers, and other non-relevant papers were removed, a total of 535 papers remained for screening. We also enriched the search by examining germane journals and reviewed reference lists from retrieved publications to identify additional manuscripts not captured by the searches. Seven additional manuscripts were identified as meeting inclusion criteria through this method.

Study Selection Criteria

All potentially relevant publications were then evaluated by 4 individuals and were included in this review if they addressed any of the following outcomes: (1) prevalence, incidence, or clearance of anal HPV infection, (2) prevalence of anal cytological or histological neoplastic abnormalities, or (3) incidence or risk of anal cancer. Publications were excluded if they were case reports, did not include original data, did not include women, or did not stratify data by gender, or did not report results related to the aforementioned outcomes. Initial search terms yielded 244 publications for anal HPV infection and cytological and histological pathology; 37 publications addressing anal HPV infection and anal cytology remained after applying selection criteria, with 23 publications that presented findings on both outcomes. Two-hundred and ninety-one publications were identified for the anal cancer search terms, of which 23 met selection criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1. Systematic Review Process for searching Published Literature with Defined Search Terms from January 1, 1997 through September 30, 2013.

Data Extraction

For all publications, we recorded the following variables: study location, years of study, methodology, number of participants, and a description of the study population including HIV-status. We grouped together publications from the same cohort or population in our tables when appropriate and included the most recent and complete prevalence data presented. The final column in each table allowed us to present the unique findings from each publication. For publications evaluating HIV-positive women, we recorded the effect of HIV viral load on HPV detection, cytologic or histologic outcomes based on whichever the primary outcome reported was reported in the paper. For the anal HPV publications, we recorded the method of HPV testing, incidence/prevalence findings, and concurrent cervical HPV testing findings, if available. Methods of HPV testing included PCR, and hybrid capture2 (HC2). The publications varied by overall HPV types detected (high risk or oncogenic HPV genotypes only or high risk combined with low risk) as well as which specific HPV genotypes were included. Of note, there is lack of standardization of HPV testing in the anus (as in the cervix). HPV testing by PCR allows for the identification of specific high and low risk HPV genotypes, but HC2 testing does not allow for HPV genotyping, only aggregate data for high risk genotypes or low risk genotypes are available through HC2 tests. In addition, PCR has been shown to have a higher sensitivity for detecting low-level HPV infection compared to HC2.8,9

For the anal cytology publications we recorded prevalence of abnormal anal cytology findings, criteria for undergoing high-resolution anoscopy (HRA), number of individuals who received HRA and prevalence of abnormal histologic findings. Several publications evaluated both anal HPV prevalence and prevalence of abnormal anal cytology. For those publications that presented both outcomes, we divided the outcomes and presented the HPV findings with all the other HPV publications, and the cytology findings with the other cytology publications. For the anal cancer publications, we recorded the anal cancer incidence described in each publication and included the standardized incidence ratio if available and other factors associated with increased incidence of anal cancer identified by the publication.

Results

Study Characteristics

A total of 60 publications were included in the review. Many of the publications were conducted in women with specific risk factors for anal cancer. Of the anal HPV prevalence publications, 10 publications specified that the population included only HIV-positive women. Among the publications that did not specify HIV infection, 6 publications were conducted in women with a history of abnormal cervical cytology or IN1+ of the lower genital tract, 1 publication was conducted among women with non-HIV related immune suppression and 9 publications were conducted in the general female population. Among the publications evaluating anal cytological findings, 14 publications evaluated study cohorts of HIV-positive women, twelve publications evaluated study cohorts of women with abnormal cervical cytology or intraepithelial neoplasia (IN) 1+ of the lower genital tract; and seven publications assessed anal cytology among the general population. Among the anal cancer publications there were 7 publications among HIV-positive women, 7 publications evaluated women with a history of HPV-related disease of the vulva or cervix, and 9 publications included women from the general population.

Synthesis of Results

Anal HPV infection in HIV-positive women

There were ten publications, utilizing 7 different study cohorts that specifically evaluated the prevalence and/or incidence of anal HPV infection in HIV-positive women (Table 1). With the exception of two papers,8,10 all publications reported data on HR-HPV. The prevalence of anal HR HPV was calculated from baseline, point prevalence or cross-sectional data from the seven study cohorts.8,11-16 Two publications calculated incidence of new anal HPV infections from cohort studies.15,17 Six of the seven study cohorts were from the United States.8,11-15 Most publications used polymer chain reaction (PCR) to test for HPV although the publications differed in HPV types detected (see table 1 footnotes). Three publications utilizing PCR combined LR and HR HPV for their prevalence data.8,10,17 One publication used both PCR and hybrid capture 2 test (HC2),8 and one cohort used HC2 only.11,15 Prevalence of HPV in the anus (16-85%) was higher than that of the cervix (17-70%) in the majority of publications. Concordant HPV genotypes between the anus and cervix were found in 9-16% of HIV-positive women (compared with only 2% having concordant HPV genotypes in the HIV- matched cohorts).

Table 1. HR-HPV anal infection in HIV-positive women.

| Study | Location | Years of study | Study design | No. of subjects | Population (age)* | Methodology for HPV testing | Anal HR- HPV Prevalence n (%) | Cervical HR- HPV Prevalence n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durante12 | US | 1995-1998 | Baseline data from cohort study | 86 | HIV+ with negative anal cytology (M=38) | PCR1 | 38 (44) | 27 (31) |

|

| Goncalves16 | Brazil | 1996-1997 | Cross-sectional | 102 | HIV+ | PCR2 | 44 (43) | 51 (37) |

|

|

Hessol 200913 Hessol 201329 |

US | 2001-2003 | Point prevalence data within a cohort study | 470 | HIV+/WIHS | PCR3 | 188 (40) | 81 (17) |

|

| Kojic14 | US | 2004-2006 | Baseline data from cohort study | 120 | HIV+/SUN (Mdn=38) | PCR4 | 102 (85) | 84 (70) |

|

|

Tandon11 Baranoski15 |

US | 2006-2010 | Baseline prevalence and incidence data from cohort study | 100 | HIV+ (M=40) | HC2 | 16 (16)5 | 24 (24) |

|

| The following publications did not separate the findings based on LR vs. HR HPV | |||||||||

| Location | Years of study | Study design | No. of subjects | Population (age)* | Methodology for HPV testing | Anal (HR + LR) HPV Prevalence n (%) | Cervical (HR + LR) HPV Prevalence n (%) |

|

|

|

Mullins17 Moscicki 200310 |

US | 1996-2001 | Cohort study | 183 | HIV+ adolescent (REACH) (M=17) | PCR (HR + LR) | 59 (32)6 | ….. |

|

| Palefsky8 | US | 1995-1997 | Point prevalence data within a cohort study | PCR: 223 HC2 242 |

HIV+/WIHS (M=40) | PCR (HR + LR) HC2 (HR + LR) |

170 (76)6 182 (75)6 |

106 (53) |

|

Mean or median age reported when available: M = mean, Mdn = median

HPV = human papillomavirus, HR = high risk; LR = low risk, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, HC2 = hybrid capture 2

WIHS = Women's Interagency HIV Study

SUN = Study to Understand the Natural History of HIV/AIDS in the Era of Effective Therapy

OR = Odds Ratio

REACH = Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health

aRR = Adjusted Relative Risk

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, and 73

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, 82

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 66

HR types 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 73, 82, IS39

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68

HPV prevalence only reported as combined LR + HR types

The most common prevalent HPV types identified in the anus were 16, 53, 45, 52, 18 and 35 (compared with the concurrent cervical HPV types 16, 52, 53, 58, and 31). Baranoski et al.,15 reported the incidence of new anal HR-HPV infections was 74/1,000 person years for HIV-positive women over an average follow-up time of 704 days. Risk factors for prevalent anal HPV included cervical HPV,8 CD4 < 200,8 smoking,14 and perianal warts.10,17 CD4 ≥ 50014 was shown to be significantly protective for anal HPV infection. Of note, reported history of anal intercourse was not associated with anal HPV.8,14 Only one publication, Palefsky et al., 8 evaluated the effect of most current HIV viral load on the detection of both high risk and low risk HPV types by both HC and PCR, and did not find any differences in detection of HPV using either method between individuals with high HIV viral load compared to low HIV viral load.

Anal HPV infection in predominantly HIV negative female cohorts

Eighteen publications (representing 13 different study cohorts) reported data on anal HPV prevalence, incidence, or clearance in women not known to be HIV positive (Table 2). The 13 study cohorts varied widely by age, recruitment criteria, population pool and other inclusion criteria. Six of the cohorts were recruited from women attending colposcopy clinics;18-23 however, the inclusion criteria among these cohorts varied from an abnormal referral cervical cytology, to histologic CIN3+.

Table 2. HR-HPV anal infection in predominantly HIV-negative female cohorts.

| Study | Location | Years of Study |

Study design |

No. of subjects |

Population (age)* |

Methodology for HPV testing |

Anal HR- HPV Prevalence n (%)** |

Cervical HR- HPV Prevalence n (%)** |

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park21 | US | 2006-2007 | Cross- sectional | 92 | IN2+ lower genital tract (including Ca) (HIV+ :N=1) (M=32) | PCR | 33 (36)1 | ….. |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Valari22 | Greece | 2009-2011 | Cross-sectional | 235 | IN1+ (including cervical Ca: N=20 and vulva Ca: N=1) (M=34) | PCR mRNA (flow) |

72 (31)2 19 (8)3 |

91 (39) 60 (26) |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Veo23 | Brazil | ….. | Cross-sectional | 40 | CIN3 (M=33) | HC2 | 9 (23)4 | 39 (98) |

|

|||||||||||||||

| 40 | Gynecology clinic (no CIN 3) (M=40) | HC2 | 2 (5)4 | 3 (8) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Goodman 200825 Shvetsov28 |

US | 1998-2003 | Cohort study | 431 | Subset of Hernandez (2005) *** (M=39) | PCR | 96 (22)5 | 143 (33) |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Goodman 201026 | US | 1998-2008 | Cohort study | 751 | Subset of Hernandez (2005) *** (M=34) | PCR | ….. | ….. |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Hernandez 201327 | US | 2008-2009 | Cross-sectional | 211 | Women, community (M=40) | PCR | 8 (4)6 | 11 (5) |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Pierangeli et al.30 | Italy | 2005-2011 | Cross-sectional | 134 | HIV-proctology clinic ¥ (M=42) | PCR | 18 (13)7 | 13/108 (12) |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Hessol 200913 Hessol 201329 |

US | 2001-2003 | Point prevalence within a cohort study | 185 | HIV-(WIHS) (M=29) | PCR | 28 (15) | 13 (1) |

|

|||||||||||||||

| The following publications did not separate the findings based on LR vs.HR HPV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Years of study | Study design | No. of subjects | Population (age)* | Methodology for HPV testing | Anal (HR + LR) HPV Prevalence n (%) |

Cervical (HR + LR) HPV Prevalence n (%) |

|

||||||||||||||||

| D'Hauwers18 | Belgium | 2007-2008 | Cross-sectional | 96 | Colposcopy clinic: N=61 Gynecology clinic: N=35 (M=30) |

PCR (HR+LR) | HR+LR 54 (56) **8 |

HR+LR 59 (61) ** |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Crawford19 | UK | 2009-2010 | Cross-sectional | 100 | Colposcopy clinic (M= 34) | PCR (HR +LR) HPV16 HPV31 |

84 (90) **#9 52/93 (56) 20/93 (22) |

96 (96)** 55 (53) 24 (24) |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Heraclio20 | Brazil | 2008-2009 | Cross-sectional | 303 | CIN1+ (including Cervical Ca: N=26) (HIV+ :N=8) | PCR (LR + HR) | 255 (84)**10 | ….. | ….. | |||||||||||||||

| Castro31 | Costa Rica | 2004-2005 | Cross-sectional | 2107 | Women, community (22-29 years) | PCR HR+LR PCR HR only |

666 (32) ** 464 (22)11 |

768 (36) ** n/a |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Hernandez 200524 | US | 1998-2004 | Baseline data from cohort study | 1378 | Women, community | PCR (LR + HR) | 368 (27)**12 | 369 (27) ** |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Mullins17 Moscicki 200310 |

US | 1996-2001 | Cohort study | 82 | HIV-adolescent (REACH) (M=17) | PCR (HR + LR) | 11 (13) ** | ….. |

|

|||||||||||||||

| Palefsky8 | US | 1995-1997 | Point prevalence within a cohort study | PCR: 57 HC2: 67 |

HIV- Subset of WIHS (M=40) | PCR (HR + LR) HC2 (HR + LR) |

24 (42)**13 HC2: 20 (30) |

12 (24) | ….. | |||||||||||||||

Mean or median age reported when available: M = mean, Mdn = median

Publications reporting only combined HR and LR HPV data (and not separating out the HR HPV): Castro, Crawford et al., D'Hauwers, Goodman et al. (2010), Heraclio et al., Hernandez et al., and Palefsky et al.

Note that these publications are a subset of the cohort from Hernandez (2005) with sufficient follow-up

Cohort has no history of HPV-related pathologies

Seven anal specimens were unable to be evaluated for HPV.

HPV = human papillomavirus, HR = high risk; LR = low risk, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, HC2 = hybrid capture 2

WIHS = Women's Interagency HIV Study

REACH = Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health

CIN = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia,

IN1+ = intraepithelial neoplasia of the lower genital tract (cervical, vaginal or vulvar) grade 1 or higher

HR types 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35,39, 45, 51–53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82, and IS39

HR types not stated

Flow cytometry for E6&7 mRNA of 14 high-risk HPV types (not stated)

HR types not stated

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 70, 73, and 82

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68; possible HR 26, 34, 53, 66, 70, 73, and 82

HR types 6 E6, 11 E6, 16 E7, 18 E7, 31 E6, 33 E6, 35 E6, 39 E7, 45 E7, 51 E6, 52 E7, 53 E6, 56 E7, 58 E6, 59 E7, 66 E6, 67 L1 and 68 E7

HR types 16, 31, 33, 53, 59, 45, 56, 18, 66; probable HR-HPV types 26, 35, 39, 51, 52, 58, 68, 69, 70, 73, 82, IS39; LR-HPV types 6, 11, 40, 42, 54, 61, 72, 81, CP6108; undetermined risk types 55, 62, 64, 67, 71, 83 and 84

HR types not stated

HR types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68/73b

HR types 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71,72, 73, 81, 82, 83, 84, CP6108, and IS39

HR types 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 32, 33, 35, 39, 40, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 66, 68, 69, 70, 73, AE2, Pap 155, Pap 291, 2, 13, 34, 42, 57, 62, 64, 67, 72, W13B

The majority of publications were cross-sectional. Study cohort size ranged from 40 to 2,107 participants. Eleven of the publications were done in the United States,8,10,13,17,21,24-29 four in Europe,18,19,22,30 and three in Central/South America.20,23,31 The vast majority of publications used PCR to test for HPV. Eight publications utilized PCR combined LR and HR HPV for their prevalence data.8,10,17-20,24,31 Two publications used PCR and either HC2 or flow cytometry,8,22 and one publication used only HC2.23 Ten publications reported prevalence of anal HR-HPV infection in their study cohorts ranging from 4 - 36%.13,21-23,25-30 The prevalence of anal HR- HPV in women with HPV-related pathology of the vulva, vagina and cervix compared with women with no known HPV-related pathology, varied from 23 - 36%21-23 compared with 4-22%13,23,25,27-30 respectively. Veo et al.,23 reported the prevalence of HPV in the anal canal of the women with CIN III was greater than in the women without CIN III (p=0.014). Several publications found that detection of cervical HPV were associated with prevalent anal HPV infection.22-25,27,31 Other risk factors for anal HPV detection among HIV-negative women include: reported history of anal intercourse;31 number of lifetime partners;25,31 and history of perianal and/or vulvar condyloma.17 Hernandez (2013) et al.,27 found that age < 30 increased the risk for anal HPV and Goodman et al.,25 found that age > 45 decreased the likelihood of anal HPV.

The data regarding incidence and clearance of anal HR HPV infection were reported from the Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health Project (REACH) and Hawaii Cohorts. The REACH cohort (mean age 17) reported an incident anal HR-HPV infection rate of 5.3/100 person-years,17 whereas the Hawaii cohort (mean age 39) reported an incident anal HR-HPV infection rate of 19.5/1000 person-months.25 In this Hawaii cohort the mean duration of anal HR HPV infection was 5 months (compared to cervical HR HPV infections which lasted a mean of 8 months) and the clearance rate of anal HPV was 9.16/100 woman-months.28 A longitudinal study of cervical and anal HPV infection (Hawaii cohort) found the risk of anal HPV infection after cervical infection with concordant genotype was 20.5 (95% CI, 16.3–25.7); compared with the risk of a cervical HPV infection after an anal HPV infection with a concordant genotype was 8.8 (95% CI, 6.4–12.2).26

Results of anal cytology and histology in women

Tables 3 and 4 summarize publications that evaluated abnormal anal cytology and/or histology in women. Ten publications reported results for only women living with HIV,11,12,14,15,32-37, three publications reported comparative results for both HIV-positive and negative women.10,13,38

Table 3. Prevalence of abnormal anal cytology and histology in HIV-positive women.

| Study | Location | Years of study |

Sample size |

Population (Age)* |

Subjects with abnormal anal cytology |

Criteria for HRA (n) |

Subjects with AIN (histology) n (% with HRA) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All abnormal n (%) |

HSIL or ASC-H n (%) |

AIN1-3 n (%) |

AIN2-3 n (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abramowitz32 | France | 2003-2004 | 150 | HIV+ ID clinic | ….. | ….. | All 150 women underwent anoscopy | 10 (7)1 | ….. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chaves33 | Brazil | 2006-2008 | 184 | HIV+ STD clinic (M=36) | 26 (14) | 0 | ….. | ….. | ….. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Durante12 | US | 1995-1998 | 100 | HIV+ (M=35) | 14 | 0 | ….. | ….. | ….. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gaisa34 | US | 2009-2012 | 556 | HIV+ ID clinic (M=48) | 233 (42%) | 29 (5%) | Abnormal anal cytology (170) | 115 (68) | 45 (26) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gingelmaier35 | Germany | 2007-2008 | 104 | HIV+ gynecology clinic (M=38) | 13 (13) | 2 (2) | Abnormal anal cytology (13) | 6 (46) | 4 (31) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hessol 200913 | US | 2001-2003 | 470 | HIV+ (WIHS) (M=33) | ….. | ….. | Abnormal anal cytology (n/a) | 68 (92)2 | 37 (50)2 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Holly38 | US | 1995-1997 | 235 | HIV+ (WIHS) | 61 (26) | 2 (1) | Abnormal anal cytology (46) | 33 (72) | 14 (30) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hou36 | US | 2008-2010 | 715 | HIV+3 (M=49) | 75 (10) | 4 (0.6) | Abnormal anal cytology (75) | 54 (72) | 29 (29) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kojic14 | US | 2004-2006 | 120 | HIV+ (SUN) (M=38) | 46 (38) | 4 (3) | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moscicki 200310 | US | 1996-2001 | 162 | HIV+ adolescents (REACH) (M=17) | 34 (21) | 4 | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tandon11 | US | 2006-2007 | 100 | HIV+ ID clinic (M=40) | 17 (17) | 0 | Abnormal anal cytology or HR-HPV infection (HC2) (14) | 10 (10) | 3 (3) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baranoski15 | 2006-2010 | 33 | 0 | Abnormal anal cytology or HR-HPV infection (HC2) (36) | ….. | 12 (12) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tatti39 | Argentina | 2005-2011 | 31 | HIV+ IN1-3 (M=37) | ….. | ….. | All participants (31) | 16 (52) | 8 (26) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weis37 | US | 2006-2008 | 204 | HIV+ ID clinic (M=40) | 64 (31) | 1 (0.5) | Abnormal anal cytology (51) | 50 (98) | 35 (69) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Mean Age reported when available: M = mean

HSIL = high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion

ASC-H = Atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out high grade

HRA = high resolution anoscopy

ID = infectious disease

CIN = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

VaIN = vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

VIN = vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

PAIN = perianal intraepithelial neoplasia

AIN = anal intraepithelial neoplasia

IN1+ = intraepithelial neoplasia of the lower genital tract (cervical, vaginal or vulvar), grade 1 or higher

WIHS = Women's Interagency HIV Study

SUN = Study to Understand the Natural History of HIV/AIDS in the Era of Effective Therapy

REACH = Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health

h/o = history of

combined AIN1-3 as “dysplasia”

numbers don't add because grade of the lesion was defined as the more advanced diagnosis on cytology or histology. If no histological data was available, grade based only on cytology.

no gross anal disease on physical exam

Table 4. Prevalence of abnormal anal cytology and histology in predominantly HIV- female cohorts.

| Study | Location | Years of study |

Sample size | Population (age)* |

Subjects with abnormal anal cytology |

Criteria for HRA (n) |

Subjects with AIN (histology) n (% with HRA) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any n (%) |

HSIL or ASC-H n (%) |

AIN1-3 n (%) |

AIN2-3 n (%) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calore46 | Brazil | Not stated | 49 | CIN1+ by cytology (no gross anal lesions) (M=32) | 29 (59) | 14 (29) | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D'Hauwers18 | Belgium | 2007-2008 | 93 | H/o abnormal cervical cytology: N=58 Normal screening: N=35 (M=30) | 10 (11) | 0 | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

El Naggar 201341 El Naggar 201242 |

US | 2006-2010 | 324 | IN1+ (including cervical Ca: N=4) (HIV+: N=16) (other immunosuppression: N=12) (M=39) |

18 (6) | 1 (0.3) | All participants (324) | 64 (20) | 28 (9) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heraclio20 | Brazil | 2008-2009 | 324 | CIN1+ (Including cervical Ca: N=26) (HIV+ : N=8) | 102 (31) | 10 (3) | All participants (324) | 13 (4) | 8 (2) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jacyntho43 | Brazil | 2003-2004 | 184 | IN1-3 (72% < age 40) | ….. | ….. | All participants (184) | 32 (17) | 6 (3) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 74 | No h/o IN1-3 (72% < age 40) | All participants (74) | 2 (3) | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Koppe44 | Brazil | 2008-2010 | 106 | IN1-3 (38) | ….. | ….. | All participants (106) | 11 (10) | 5 (5) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 74 | HIV-(no IN1-3) (M=50) | All participants (74) | 1 (1) | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Park21 | US | 2006-2007 | 102 | IN2+ lower genital tract (including Ca) (HIV+: N=1) (M=32) |

9 (9) | 2 (2) | Abnormal anal cytology (7) | 7 (100) | 0 | ….. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Santoso40 | US | 2006-2009 | 205 | Women with genital intraepithelial neoplasia (HIV+ : N=10) | 12 (6) | 0 | All participants (205) | 25 (12) | 17 (8) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Likes47 | US | 2006-2009 | 310 | abnormal cervical cytology or vulvar lesion (M=40) | Immune-competent | ….. | ….. | All participants (310) | 61 (19) | 26 (8) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | Immune-compromised1 | All participants (33) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tatti39 | Argentina | 2005-2011 | 404 | Immune-competent IN1-3 (M=30) |

….. | ….. | ….. | 104 (26) | 16 (4) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46 | Immune-compromised IN1-3 (HIV-)2 (M=40) |

All participants (46) | 15 (33) | 4 (9) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valari22 | Greece | 2009-2011 | 235 | IN1+ (including Ca: N=21) (M=34) |

….. | ….. | Abnormal anal cytology or positive HPV DNA or mRNA (25) | 8 (32) | 0 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hessol 200913 | US | 2001-2003 | 185 | HIV- (WIHS) (M=29) |

….. | ….. | Abnormal anal cytology | 7 (9) | 2 (3) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Holly38 | US | 1995-1997 | 61 | HIV-(WIHS) | 5 (8) | 0 | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moscicki 200310 | US | 1996-2001 | 67 | HIV- adolescents (REACH) (M=17) |

4 (6) | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pierangeli30 | Italy | 2005-2011 | 109 | HIV- proctology clinic4 (M=42) |

38 (35) | 0 | ….. | ….. | ….. | ….. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moscicki 199945 | US | 1994 | 410 | HIV-family planning clinics (M=23) | 16 (4) | 0 | Abno mal anal cytology (9) | 5 (56) | 2 (22) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Age or mean age reported when available: M = mean

HSIL = high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion

ASC-H = Atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out high grade

HRA = high resolution anoscopy

CIN = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

VaIN = vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

VIN = vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

PAIN = perianal intraepithelial neoplasia

AIN = anal intraepithelial neoplasia

IN1+ = intraepithelial neoplasia of the lower genital tract (cervical, vaginal or vulvar), grade 1 or higher

Ca = cancer

WIHS = Women's Interagency HIV Study

REACH = Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health

h/o = history of

Immune-compromised-- 16 were HIV-positive, 5 were transplant patients, 7 had lupus and 1 had diabetes, 1 had celiac Bruce disease and 1 had Crohn's disease.

Immune compromised by other causes—HIV- but otherwise not specified.

Study reports “high fallout rate” but rate not specified-- (4/19 with + HPV, and unknown of abnormal cytology)

Women seen at a proctology clinic with no history of HPV-related pathologies

Twelve publications evaluated study cohorts of women with abnormal cervical cytology or IN1+ of the lower genital tract. Five of these 12 publications included a small number of HIV+ women,20,21,40-42 one publication included a cohort of HIV-positive women with IN1-3 (compared with HIV-negative immune compromised and HIV-negative immune competent with IN1-3),39 and two publications included a comparative cohort of women without a history of IN1-3.43,44 Two publications included only women from the general population.30,45 The prevalence of cytologic high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) was 0 - 5% of women living with HIV,10-12,14,15,33-38 0 - 29% among women with lower genital HPV disease,18,20,21,40,41,46 and 0 – 0.3% among women who were HIV-negative with unspecified or no known genital HPV.10,13,30,38,45 Among HIV-positive women, 5 publications evaluated the effect of HIV viral load on abnormal anal cytologic findings, and none of the publications found that HIV viral load was associated with detection of abnormal anal cytology.11,15,33,35,38

Twenty publications reported histology results from high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) (Tables 3 and 4). HRA examination was done on all participants in seven publications.20,39-41,43,44,47 In the remaining ten reports, HRA was performed only on those with abnormal anal cytology13,21,35-37,45 or as in the publications on those with abnormal anal cytology or anal HPV infection.11,15,22 Abramowitz et al.,32 reports on biopsies from simple anoscopy. Histologic anal HSIL (AIN 2+) was found in 3-26% of the women living with HIV,11-15,32-39 0 – 9% among women with lower genital tract pathology,20-22,39-44,47 and 0-3% for women who are HIV-negative without known lower genital tract pathology.13,43-45 In a publication of women with intraepithelial neoplasia (IN) 1+ who were either HIV-positive, immunosuppressed and HIV-negative, or immunocompetent, the prevalence of AIN2/3 was 26%, 9%, and 4% respectively (p<0.001).39 Among HIV-positive women, 4 publications the effect of HIV viral load on histologic diagnosis of Histologic anal HSIL (AIN 2+).13,17,32,36 Hou et al36 found that poor HIV-control was associated with a higher percentage of histologic anal HSIL detection in a univariate analysis of 75 women. Mullins et al17 found that poor HIV-control was associated with a higher risk of anal condyloma (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.12-2.17) in a multivariable analysis, but there was no effect of HIV viral load control on anal dysplasia risk in 278 HIV-infected adolescent women. The other two publications did not find an association between HIV virologic control and histologically defined anal dysplasia.

Anal cancer in women

Twenty-three publications describing the incidence rates (IR) or standardized incidence ratio (SIRs) of anal cancer involving women were included in this review (Table 5). Of these publications, 11 included women in the North America48-58 and the majority of the other publications were from Europe (United Kingdom and Scandinavia).59-71 Seven publications identified women living with HIV.50-53,64-66 Four publications evaluated the IR or SIR in women with CIN3, cervical cancers or other HPV-related genital cancers,48,49,61,62 and three other publications evaluated the SIR of anal cancer in women with genital warts.59,60,63 Nine publications reported IRs and risk factors of anal cancer within the general population.54-58,68-71

Table 5. Incidence of anal cancer in women.

| Study | Location | Years of study |

Population | Study design | Total no. of patients in cohort |

No (%) women in cohort |

Risk factor | Anal cancer incidence (95% CI) in women per 100,000 person-years |

Standardized Incidence Ratio (SIR) for Anal Cancer and other Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Blomberg59 Friis60 1 |

Denmark | 1978 – 2008 | Patients with genital warts† | Danish National Patient Register | 49,088 | 32,933 (67) | Genital warts | Not Reported |

|

| Chaturvedi48 | Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, US | Varies by registry2 | One-year survivors of cervical cancer† | 13 population based cancer registries from 5 countries | 104,760 | 104,760 (100) | Cervical cancer | 63.8 (no CI reported) |

|

| Edgren61 | Sweden | 1968-2004 | Women aged 18-50 with history of CIN 3 | Sweden National Registry | 3,747,698 | All Women | CIN 3 |

|

|

| Evans62 | UK | 1960-1999 | Thames Cancer Registry | CIN 3: 59,519; Cervical cancer: 21,605 | All Women | CIN 3 or cervical cancer |

|

|

|

| Nordenvall63 | Sweden | 1965 – 1999 | Hospitalized patients with condylomata acuminata† | Sweden inpatient register and nationwide registers | 10,971 | 9,286 (85) | Genital warts | 4.8 (No CI reported) |

|

| Saleem49 | US | 1973 – 2007 | Patients with either in situ or invasive cervical, vulvar, or vaginal neoplasm† | SEER | 189,206 | All Women | HPV-related gynecologic neoplasm | 0.8 (No CI reported) |

|

| Hessol50 | US | 1994-2001 | HIV-positive women over the age of 18 | Women's Interagency HIV study & SEER | 1559 HIV-positive women 391 HIV-negative | All Women | HIV | Not reported |

|

| Fordyce51 | US | 1981 – 1994 | Women with AIDS, ages 15-69 | New York State Cancer Registry and New York City AIDS registry | 15,146 | All Women | HIV | Not reported | |

| Franzetti64 | Italy | 1985-2011 | HIV-positive patients† | L Sacco Department of Clinical Science at the University of Milan | 5,924 | 1,542 (26) | HIV | 13.8 (no CI reported) |

|

| Frisch (JNCI)52 | US | 1995 -1998 | Patients with HIV/AIDS† | AIDS-cancer registry match in 11 state and metropolitan locations4 | 309,365 | 51,760 (40) | HIV | 3.9 (No CI reported) |

|

| Lanoy65 | France | 2006 | HIV-positive patients with incident cases of cancer† | ONCOVIH cohort and FHDH | 53,853 | Not Reported | HIV | Not Reported |

|

| Piketty66,67 5 | France | 1992-2008 | HIV positive patients | French Hospital Database on HIV | 109,771 | Not Reported | HIV | 9.4 (No CI Reported) |

|

| Silverberg53 | US, Canada | 1996-2007 | HIV-positive and negative women† | NA-ACCORD, SEER | 8,842 HIV-positive women 11,653 HIV-negative women | 20,495 | HIV | 30 (17-50) |

|

| Benard54 | US | 1998-2003 | Incident cases of HPV-associated cancers, Women ≥ 20 years of age | CDC, NPCR, SEER, BRFSS data | 138,043 | 95,961 (70) | General Population | 2.14 (2.10, 2.19) |

|

| Brewster68 | UK | 1975-2002 | Incident cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus† | Scottish Cancer Registry | Not Reported | Not Reported | General Population | 0.557 |

|

| Fisher55 | US | 1985 -1992 | Incident cancers of the lower anogenital tract in women† | Michigan Tumor Registry | Not Reported | Not Reported | General Population | 0.7 (No CI Reported) |

|

| Frisch (Cancer)56 | US | 1973 – 1996 | Incident cases of squamous cell carcinoma of cervix, vulva, vagina, anus, penis, and tonsils† | SEER (Hawaii and 8 other locations)8 | Not Reported | Not Reported | General Population |

|

|

| Jin69 | Australia | 1982-2005 | Incident cases of invasive anal cancer† | Australian National Cancer Statistics Clearing House database | Not Reported | Not Reported | General Population | 1.10 (1.02 – 1.18)*9 Rate adjusted to the 2001 US standard population |

|

| Joseph57 | US | 1998-2003 | Incident cases of all types of anal cancer | NPCR, SEER (83% of US population) | Not Reported | Not Reported | General Population | 1.51 (1.48 –1.54)* rate adjusted to the 2000 US standard population |

|

| Nelson58 10 | US | 1973-2009 | Incident cases of anal adenocarcinoma (AAC) or anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) | SEER database | Not Reported | Not Reported | General Population | 2.4 (2.3 – 2.5)*11 Rate adjusted to the 2000 US standard population |

|

| Nielsen70 | Denmark | 1978 – 2008 | Incident cases of anal cancer | Danish Cancer Registry and Danish Registry of Pathology | 5.5 million | Not reported | General Population | 1.48*12 (No CI reported) |

|

| Robinson71 | UK | 1960-2004 | Incident cases of anal, vulvar, vaginal, cervical, and penile cancers† | Thames Cancer Registry | 12 million | Not reported | General Population | 1.18*13 (No CI reported) |

|

age standardized incidence rate

No age range reported

SIR = standardized incidence ratio

Denmark 1943 – 1998, US SEER 1973 – 2001, Sweden 1958 – 2001, Norway 1953 – 1999, Finland 1953 – 2001

Cancers of rectum and anus combined

Atlanta, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Los Angeles, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York City/State, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle

for time period 2005 – 2008

for time period 1998 – 2002

San Francisco-Oakland, Detroit, Atlanta, Seattle, Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, and Utah

for the time period 2000 – 2005

Data in the table is from58, is a previous analysis of the same data

for time period 1997 - 2009

for the time period 2003 – 2008

for time period 2000 – 2004

The incidence of anal cancer among HIV-positive women ranged from 3.9-30 per 100,000 among the 4 publications that reported incidence rates.52,53,64,66 The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) ranged from 3.2 to 41.2 compared to the general population.50,51,64,66 There was only one publication that compared HIV-positive and HIV-negative women and found that the SIR for HIV-positive women was 18.5 and the SIR for HIV-negative women studied was 0.50 In addition, other publications demonstrated that the standardized incidence ratio was higher among subsets of HIV-positive women. For example, Piketty et al.,66 and Silverberg et al.,53 found that the SIR among women diagnosed more recently (2005-2008 for Piketty and 2004-2007 for Silverberg) were both higher than SIRs in earlier years. Other publications also found that the SIR and relative risk (RR) among younger women was higher than among older women.52,66 Of note, the lowest SIR (3.23) included only women through 1994, and therefore did not include women diagnosed during the era of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) era.51

Among women with a history of cervical cancer or CIN 3, the IR of anal cancer ranged from 0.8-63.8/100,000 person years;48,49,61,62 however, it should be noted that the 63.8/100,000 IR reported by Chaturvedi et al.,48 included rectal cancers as well as anal cancers. The SIRs ranged from 1.8,48 (including women with rectal cancer) to 13.649. The SIRs for anal cancer in women with genital warts ranged from 7.8,59 to 9.0.63

In the general female population, the IRs ranged from 0.55/100,000 person-years to 2.4/100,000 person-years.54-58,68-71 Nelson et al.,58 reported the highest incidence rate (2.4, CI 2.3-2.5) and included cases through 2009, which is the most up to date publication. Multiple publications from different countries found that the incidence of anal cancer has been increasing over the past several decades.56-58,69-71 In addition, several publications also reported that individuals with lower median household income had significantly higher rates of anal cancer.54,68

Comment

Main Findings

Our systematic review of the literature revealed that anal HPV infection in women is prevalent in general, and comparable to rates of cervical HPV infection. In particular, HIV positive women and women with HPV-related pathology of the lower genital tract were found to have high rates of HR -HPV infection, high rates of high-grade anal intraepithelial lesions (AIN 2+) on biopsy, and elevated rates of anal cancer. Of note, few longitudinal publications evaluating anal HR HPV infection and AIN 2+ on women have been conducted, thus there are few publications describing the natural history of HR HPV infection in HIV-positive, or HIV negative women. In addition, for all populations, the retrospective publications evaluating anal cancer incidence in women demonstrate a significant increase in anal cancer incidence during the last several decades.

The prevalence of HR-HPV anal infection appears to be higher among women who are HIV-positive and women with HPV-related lower genital tract disease compared with that in the general population. Publications with both HIV-positive and negative cohorts found that HIV infection was associated with an increased prevalence of anal HPV,8,13 consistent with the findings of a meta-analysis on anal HPV infection in men who have sex with men (MSM), which reported a greater pooled prevalence of anal HR-HPV in HIV-positive men than in HIV-negative men (p=0.010).72

Interestingly, all of the reporting simultaneously collected specimens for HPV from the cervix and the anus found comparable or higher detection rates of HR-HPV in the anus compared with the cervix. Most publications found that HPV infection of the cervix was a significant risk factor for anal HPV. In addition, there was significant concordance of HR-HPV genotypes between the cervix and anus. Reported history of prior anal intercourse was not a consistent risk factor for anal HPV. This data supports the likelihood that HPV has a field effect on the lower genital tract; that anal HPV is often found in women who have no history of anal receptive intercourse, and that anal HR HPV infection is as prevalent if not more prevalent than cervical HR HPV infection.

Comparison with Existing Literature

Although we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis with the publications identified for this review because of the heterogeneity in outcomes, and the small numbers of publications per outcome for women, the findings from our systematic review of women can be broadly compared to the meta-analysis and review by Machalek et al.,72 These authors conducted a meta-analysis reviewing publications evaluating the incidence and prevalence of HPV-16, -18, anal squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs) and anal cancer among men who have sex with men (MSM). Their review drew upon 31 publications evaluating HPV prevalence and 19 estimates of cytological abnormalities, and 11 publications evaluating the incidence of anal cancer. The authors were able to derive pooled prevalence and incidence estimates of both HPV-16 and -18 infection and high grade SIL (AIN 2+) lesions. In Machalek's review, the pooled incidence of high-risk HPV was 73.5 (95% CI 63.9-83.0) and 37.3 (27.4-47.0) for HIV-positive MSM and HIV-negative MSM respectively. These estimates are generally higher than the incidence and prevalence of high-risk HPV infection among both HIV-positive and negative women in the publications we reviewed.

The pooled prevalence of histological AIN2+ was found to be 29.1% (22.8-35.4) and 12.5% (9.8-15.4) among HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSMs respectively. The publications of anal HPV related disease in MSM included concurrent collection of anal HPV, anal cytology and high resolution anoscopy with directed biopsies at a single study visit. In comparison, in the majority of cohort studies conducted among women, the HRA was conducted based on abnormal anal cytology. Using this criteria, the prevalence of AIN 2+ among all female cohorts were lower than that that of MSM. Finally, Machalek et al.,72 reported that the pooled incidence of anal cancer was 45.9 per 100,000 (31.2-60.3) in the cART era and 5.1 per 100,000 (0-11.5) among HIV-positive and HIV-negative men respectively, these are higher estimates than the majority of anal cancer publications reported in our review. Thus, although the publications in women were too heterogeneous to conduct a meta-analysis, the pooled estimates from the review by Machalek et al., for high-risk HPV, AIN 2+ and anal cancer in HIV-positive and negative MSM all appear higher than those found in the majority of publications among women reviewed in our current review.

Strengths and Limitations

Our systematic review of the literature regarding anal HPV infection, neoplasia, and cancer in women revealed significant heterogeneity in both study design and findings, and results should be considered accordingly. The study cohorts included differing combinations of HIV-positive women, HIV- negative and women with unknown HIV status. In addition, a number of cohorts included women with HPV-related disease of the lower genital tract; however, the inclusion criteria varied from anogenital condyloma, vulvar lesions, abnormal cervical cytology, and specifically CIN3+. Furthermore, several publications did not separate non-oncogenic from oncogenic HPV genotype expression such that the findings cannot be compared to those publications only investigating oncogenic HPV. There was significant variance in the methodology for HPV testing from HC2 to PCR. Since cervical HPV infection has itself been identified as a risk factor for anal HPV infection,26 comparing publications that do not use a similar methodology to detect cervical HPV or HPV-related pathology will not represent the true relationship between HIV-status, cervical/vaginal/vulvar HPV-related disease and anal HPV infection. In addition, the publications of HIV-positive cohorts varied in their methods of accounting for immune reconstitution. Thus the findings vis a vis prevalence and risk factors of HPV anal infection detected in these publications varied dramatically.

Additional limitations should be considered. First, the heterogeneity of sampling methods utilized by the publications in this review may have over or under-estimated prevalence for each specific population, resulting in the large range of prevalences reported. Second, the majority of reported anal cytology results include publications that performed HRA only on those with abnormal cytology results, which may under-call the true rate of AIN2+. Third, some of the included publications reported composite anal cytological/histological diagnosis based on which was more advanced, which also only estimates true AIN2+ rates. Finally, our exclusion criteria were intentionally less rigorous in order to get a full perspective of the research that has been done to data, thus the data reported are extremely heterogeneous in regard not only to sampling method, but also study method and outcomes.

Conclusions and Implications

Despite the limitations of this review, the results of this review demonstrate the evolving importance of anal HPV-related pathology and cancer among women. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of anal HR-HPV infection, cytology, histology and anal cancer in women. Our findings show that anal HPV infection and dysplasia are common in women, especially in those who are living with HIV or have a history of HPV-related lower genital tract pathology. Furthermore, incidence of anal cancer continues to grow in all women and especially those living with HIV, despite the widespread use of cART. The lack of longitudinal data highlights the absence of conclusive knowledge in the prevention, detection, and management of anal HPV infection, dysplasia, and cancer in women. Further publications are needed to elucidate the natural history of anal HPV infection and HPV-related disorders of the anus in women in order to accurately and efficiently address this growing problem.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: NIH-funded program R01 CA163103, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN# 13-413), Michael E. DeBakey VA, Medical Center, Houston, TX, NIH-funded AIDS Malignancy Consortium U01 CA121947

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prevention CfDCa. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers--United States, 2004-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(15):258–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PS, et al. Incidence of Types of Cancer among HIV-Infected Persons Compared with the General Population in the United States, 1992–2003. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(10):728–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi AK. Beyond cervical cancer: burden of other HPV-related cancers among men and women. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4 Suppl):S20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, N A, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramowitz L, Jacquard AC, Jaroud F, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in anal cancer in France: The EDiTH V study. Int J Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/ijc.25671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moscicki AB, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, Villa LL. Chapter 5: Updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S3, 42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin-Hong PV, Palefsky JM. Human papillomavirus anogenital disease in HIV-infected individuals. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Da Costa M, Greenblatt RM. Prevalence and risk factors for anal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(3):383–391. doi: 10.1086/318071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Jay N, Berry JM, Darragh TM. High incidence of anal high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesions among HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual and bisexual men. Aids. 1998;12(5):495–503. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moscicki AB, Durako SJ, Houser J, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and abnormal cytology of the anus in HIV-infected and uninfected adolescents. Aids. 2003;17(3):311–320. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tandon R, Baranoski AS, Huang F, et al. Abnormal anal cytology in HIV-infected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(1):21 e21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durante AJ, W A, Da Costa M, Darragh TM, Khoshnood K, Palefsky JM. Incidence of anal cytological abnormalities in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention. 2003;12(7):638–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hessol NA, Holly EA, Efird JT, et al. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in a multisite study of HIV-infected and high-risk HIV-uninfected women. Aids. 2009;23(1):59–70. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831cc101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojic EM, C-U S, Conley L, et al. Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cytologic Abnormalities of the Anus and Cervix Among HIV-Infected Women in the Study to Understand the Natural History of HIV/AIDS in the Era of Effective Therapy (The SUN Study) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(4):253–259. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f70253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baranoski AS, Tandon R, Weinberg J, Huang FF, Stier EA. Risk factors for abnormal anal cytology over time in HIV-infected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):107 e101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goncalves MA, Randi G, Arslan A, et al. HPV type infection in different anogenital sites among HIV-positive Brazilian women. Infect Agent Cancer. 2008;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullins TL, Wilson CM, Rudy BJ, Sucharew H, Kahn JA. Incident anal human papillomavirus-related sequelae in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected adolescents in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013;40(9):715–720. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000431049.74390.b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Hauwers KW, Cornelissen T, Depuydt CE, et al. Anal human papillomavirus DNA in women at a colposcopy clinic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford R, G A, Kitson S, et al. High prevalence of HPV in non-cervical sites of women with abnormal cervical cytology. BMC cancer. 2011;11:473. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heraclio Sde A, Souza AS, Pinto FR, Amorim MM, Oliveira Mde L, Souza PR. Agreement between methods for diagnosing HPV-induced anal lesions in women with cervical neoplasia. Acta Cytol. 2011;55(2):218–224. doi: 10.1159/000320922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park IU, Ogilvie JW, Jr, Anderson KE, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and abnormal anal cytology in women with genital neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(3):399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valari O, K G, Karakitsos P, Valasoulis G, Founta C, Godevenos D, Dova L, Paschopoulos M, Loufopoulos A, Paraskevaidis E. Human papillomavirus DNA and mRNA positivity of the anal canal in women with lower genital tract HPV lesions: predictors and clinical implications. Gynecologic oncology. 2011;122(3):505–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veo CA, S S, Nicolau SM, Melani AG, Denadai MV. Study on the prevalence of human papillomavirus in the anal canal of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2008;140(1):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez BY, McDuffie K, Zhu X, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection in women and its relationship with cervical infection. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers and prevention. 2005;14(11):2550–2556. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman MT, S Y, McDuffie K, et al. Acquisition of anal human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in women: the Hawaii HPV Cohort study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;197(7):957–966. doi: 10.1086/529207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman MT, S Y, McDuffie K, et al. Sequential acquisition of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the anus and cervix: the Hawaii HPV Cohort Study. The Journal of i nfectious diseases. 2010;201(9):1331–1339. doi: 10.1086/651620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez BY, Ka'opua LS, Scanlan L, et al. Cervical and anal human papillomavirus infection in adult women in American Samoa. Asia Pacific journal of public health. 2013;25(1):19–31. doi: 10.1177/1010539511410867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shvetsov YB, Hernandez BY, McDuffie K, et al. Duration and clearance of anal human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among women: the Hawaii HPV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):536–546. doi: 10.1086/596758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hessol NA, Holly EA, Efird JT, et al. Concomitant anal and cervical human papillomavirusV infections and intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-infected and uninfected women. Aids. 2013;27(11):1743–1751. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283601b09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierangeli A, S C, Selvaggi C, et al. High detection rate of human papillomavirus in anal brushings from women attending a proctology clinic. The Journal of infection. 2012;65(3):255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castro FA, Quint W, Gonzalez P, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for anal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative women. Journal of Infectious Disease. 2012;206(7):1103–1110. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abramowitz L, Benabderrahmane D, Ravaud P, et al. Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and condyloma in HIV-infected heterosexual men, homosexual men and women: prevalence and associated factors. Aids. 2007;21(11):1457–1465. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281c61201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaves EB, Folgierini H, Capp E, von Eye Corleta H. Prevalence of abnormal anal cytology in women infected with HIV. J Med Virol. 2012;84(9):1335–1339. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaisa M, Sigel K, Hand J, Goldstone S. High rates of anal dysplasia in HIV-infected men who have sex with men, women, and heterosexual men. Aids. 2014;28(2):215–222. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gingelmaier A, Weissenbacher T, Kost B, et al. Anal cytology as a screening tool for early detection of anal dysplasia in HIV-infected women. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(5):1719–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou JY, Smotkin D, Grossberg R, et al. High prevalence of high grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-infected women screened for anal cancer. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(2):169–172. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318251afd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weis SE, Vecino I, Pogoda JM, et al. Prevalence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia defined by anal cytology screening and high-resolution anoscopy in a primary care population of HIV-infected men and women. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(4):433–441. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318207039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holly EA, Ralston ML, Darragh TM, Greenblatt RM, Jay N, Palefsky JM. Prevalence and risk factors for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(11):843–849. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tatti S, S V, Fleider L, Maldonado V, Caruso R, Tinnirello Mde L. Anal intraepithelial lesions in women with human papillomavirus-related disease. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2012;16(4):454–459. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31825d2d7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santoso JT, Long M, Crigger M, Wan JY, Haefner HK. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in women with genital intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):578–582. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ea1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ElNaggar AC, S JT. Risk factors for anal intrepithelial neoplasia in women with genital dysplasia. Obstetrics & gynecology. 2013;122(2 Part 1):218–213. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31829a2ace. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ElNaggar AC, Santoso JT, Xie HB. Keratosis reduces sensitivity of anal cytology in detecting anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(2):292–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacyntho CM, Giraldo PC, Horta AA, et al. Association between genital intraepithelial lesions and anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-negative women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):115 e111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koppe DC, Bandeira CB, Rosa MR, Cambruzzi E, Meurer L, Fagundes RB. Prevalence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in women with genital neoplasia. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(4):442–445. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182061b34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mosicki AB, Hills NK, Shiboski S, et al. Risk factors for abnormal anal cytology in young heterosexual women. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers and prevention. 1999;8(2):173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calore EE, Giaccio CM, Nadal SR. Prevalence of anal cytological abnormalities in women with positive cervical cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39(5):323–327. doi: 10.1002/dc.21386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Likes W, Santoso J, Wan J. A cross-sectional analysis of lower genital tract intraepithelial neoplasia in immune-compromised women with an abnormal Pap. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2013;287(4):743–747. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Gilbert ES, et al. Second cancers among 104,760 survivors of cervical cancer: evaluation of long-term risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(21):1634–1643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saleem AM, Paulus JK, Shapter AP, Baxter NN, Roberts PL, Ricciardi R. Risk of anal cancer in a cohort with human papillomavirus-related gynecologic neoplasm. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):643–649. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820bfb16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hessol NA, Seaberg EC, Preston-Martin S, et al. Cancer risk among participants in the women's interagency HIV study. Journal of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. 2004;36(4):978–985. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fordyce EJ, Wang Z, Kahn AR, et al. Risk of cancer among women with AIDS in New York city. AIDS public policy journal. 2000;15(3-4):95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frisch M, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Journal of the national cancer institute. 2000;92(18):1500–1518. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, et al. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clinical infectious diseases. 2012;54(7):1026–1034. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2910–2918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher G, Harlow SD, Schottenfeld D. Cumulative risk of second primary cancers in women with index primary cancers of uterine cervix and incidence of lower anogenital tract cancers, MIchigan, 1985-1992. Gynecological oncology. 1997;64(2):213–223. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frisch M, G MT. Human papillomavirus-associated anal carcinbomas in Hawaii and the mainland U. S. Cancer. 2000;88(6):1464–1469. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000315)88:6<1464::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joseph DA, Miller JW, Wu X, et al. Understanding the burden of human papillomavirus-associated anal cancers in the US. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2892–2900. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nelson RA, Levine AM, Bernstein L, Smith DD, Lai LL. Changing patterns of anal carcinoma in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(12):1569–1575. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blomberg M, Friis S, Munk C, Bautz A, Kjaer SK. Genital warts and risk of cancer: a Danish study of nearly 50 000 patients with genital warts. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(10):1544–1553. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friis S, Kjaer SK, Frisch M, Mellermkjaer L, Olsen JH. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, anogenital cancer, and other cancer types in women after hospitalization for condylomata acuminata. Journal of Infectious Disease. 1997;175(4):743–748. doi: 10.1086/513966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edgren G, Sparen P. Risk of anogenital cancer after diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a prospective population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(4):311–316. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans HS, Newnham A, Hodgson SV, Møllera H. Second primary cancers after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III and invasive cervical cancer in Southeast England. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nordenvall C, Chang ET, Adami HO, Ye W. Cancer risk among patients with condylomata acuminata. Internationa journal of cancer. 2006;119(4):999–893. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Franzetti M, Adorni Fulvio, PhD†, Parravicini Carlo, MD‡, Vergani Barbara, MD*, Antinori Spinello, M*, Milazzo Laura, MD*, Galli Massimo, MD*, Ridolfo Anna Lisa., MD* Trends and Predictors of Non–AIDS-Defining Cancers in Men and Women With HIV Infection: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study Before and After the Introduction of HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:414–420. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318282a189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lanoy E, Spano J, Bonnet F, et al. The spectrum of malignancies in HIV-infected patients in 2006 in France: the ONCOVIH study. International journal of cancer. 2011;129(2):467–475. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Picketty C, Selinger-Leneman H, Bouvier A, Belot A, Mary-Krause M, Duvivier C, Bonmarchand M, Abramowitz L, Costagliola D, Grabar S. Incidence of HIV-Related Anal Cancer Remains Increased Despite Long-Term Combined Antiretroviral Treatment: Results From the French Hospital Database on HIV. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(35):4360–4366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Picketty C, Selinger-Leneman H, Grabar S, et al. Marked increase in the incidence of invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected patients despite treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2008;22(10):1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283023f78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brewster DH, B LA. Increasing incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus in Scotland, 1975-2002. British journal of cancer. 2006;95(1):87–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin F, Stein AN, Conway EL, et al. Trends in anal cancer in Australia, 1982-2005. Vaccine. 2011;29(12):2322–2327. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nielsen A, Munk C, Kjaer SK. Trends in incidence of anal cancer and high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia in Denmark, 1978-2008. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(5):1168–1173. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robinson D, Coupland V, Moller H. An analysis of temporal and generational trends in the incidence of anal and other HPV-related cancers in Southeast England. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(3):527–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(5):487–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]