Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the urinary microbiota in women planning treatment for urgency urinary incontinence and to describe clinical associations with urinary symptoms, urinary tract infection and treatment outcomes.

Study Design

Catheterized urine samples were collected from female multi-site randomized trial participants without clinical evidence of urinary tract infection and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to dichotomize participants as either DNA sequence-positive or sequence-negative. Associations with demographics, urinary symptoms, urinary tract infection risk, and treatment outcomes were determined. In sequence-positive samples, microbiotas were characterized on the basis of their dominant microorganisms.

Results

Over half [51.1% (93/182)] of the participants’ urine samples were sequence-positive. Sequence-positive participants were younger (55.8 vs. 61.3, p=0.0007), had a higher body mass index (33.7 vs. 30.1, p=0.0009), had a higher mean baseline daily urgency urinary incontinence episodes (5.7 vs. 4.2, p<0.0001), responded better to treatment (decrease in urgency urinary incontinence episodes −4.4 vs. −3.3, p=0.0013) and were less likely to develop urinary tract infection (9% vs. 27%, p=0.0011). In sequence-positive samples, eight major bacterial clusters were identified; seven clusters were dominated by a single genus, most commonly Lactobacillus (45%) or Gardnerella (17%), but also other taxa (25%). The remaining cluster had no dominant genus (13%).

Conclusions

DNA sequencing confirmed urinary bacterial DNA in many women without signs of infection and with urgency urinary incontinence. Sequence status was associated with baseline urgency urinary incontinence episodes, treatment response and post-treatment urinary tract infection risk.

Keywords: Microbiota, Microbiome, Urinary Bacteria, Urgency Urinary Incontinence, Urinary tract infection, Cystitis

Introduction

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is a heterogeneous condition usually attributed to abnormalities in detrusor neuro-muscular functioning and/or signaling. However, most incontinence experts suspect that UUI etiology is likely more complex. Current first line treatment for UUI is behavioral and/or pharmacologic, but many affected patients have persistent symptoms. Thus, the group of women affected by the generic symptom of UUI may have multiple, heterogeneous etiologies.

The Anticholinergic Versus Botulinum Toxin A Comparison (ABC) Trial was a 10-center, double-blind, double-placebo-controlled randomized trial in which women received either one intradetrusor injection of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxin A and daily oral placebo or daily oral anticholinergic medication and one intra-detrusor injection of saline1. The ABC study was designed and conducted prior to knowledge that the female lower urinary tract (bladder and/or urethra) contains bacterial communities (termed the female urinary microbiome).

Growing evidence suggests that the female urinary microbiota may play a role in certain urinary disorders such as UUI2. Our research team previously described the female urinary microbiota of women with UUI3 using catheterized urine samples obtained at baseline from patientparticipants in a randomized clinical trial for the treatment of UUI who did not have clinical urinary tract infection (UTI)1. Previously, we also compared various techniques to verify that transurethral catheterization was an appropriate method to collect urine samples with minimal vulvo-vaginal contamination4. This current analysis goes beyond the initial testing of the prior samples to formally characterize the female urinary microbiota by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Relationships between sequence status, microbiota characteristics and clinical variables of interest, including treatment response and post-treatment UTI risk, were also assessed.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Specimen Acquisition

The full methods of the trial and the primary outcome of the ABC trial have been published1, 5. Briefly, the trial randomized women without neurologic disease with moderate-to-severe UUI, defined as having ≥5 episodes of UUI per 3-day period. Participants were anticholinergic drug naive or had previously used ≤2 anticholinergic medications other than the study drugs. Exclusion criteria included a post-void residual volume ≥150 mL or previous therapy with oral study medications or onabotulinumtoxin A.

The primary outcome was reduction from baseline in mean episodes of urgency urinary incontinence (UUIE) per day over the 6-month period, as recorded in 3-day diaries submitted monthly. Secondary outcomes included resolution of UUI symptoms, quality of life, use of catheters, and adverse events including UTI, which was defined as a positive standard urine culture with >105 colony-forming units of a known uropathogen or treatment with antibiotic for UTI within 6 months of randomization. Following treatment, intermittent catheterization was recommended if post-void residual was either >300mL or >150mL with “moderate” to “quite a bit” of bother associated with incomplete voiding.

All subjects were free of clinical UTI prior to study injection, as determined by a negative nitrite and leukocyte esterase result on a urine dipstick evaluation of a catheterized specimen. Urine culture was not required. Following baseline assessment and prior to injection, subjects provided a baseline catheterized urine sample, which was placed at −80°C within 1 hour; the frozen samples were batch-shipped on dry ice to Loyola University Chicago for 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Staff and investigators were blinded to clinical information during laboratory research analyses.

16S rRNA Sequencing

DNA was isolated in a laminar flow hood to avoid contamination. Genomic DNA was extracted from 1 ml of urine using previously validated protocols6–8. Variable region 4 (V4) of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified via a two-step nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol, using modified universal primers 515F and 806R, as previously described6, 87. Two quality controls assessed the contribution of extraneous DNA from laboratory reagents: a DNA extraction negative control with no urine added and a PCR negative control with no template DNA added. The final PCR product was purified from unincorporated nucleotides and primers using Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and Agencourt AMPure XP-PCR magnetic beads (Beckman coulter). Samples were normalized to equal DNA concentration, as determined by Nanodrop spectroscopy (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The sample library and the PhiX sequencing control library (Illumina) were denatured and added to the 2×250 bp sequencing reagent cartridge, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina).

DNA Sequence Analysis

Illumina MiSeq post-sequencing software preprocessed sequences, removing primers and sample indices. The open-source program mothur (v1.31.2) combined paired end reads and removed contigs (overlapping sequence data) of incorrect length (<285 bp, ϣ00 bp) and/or contigs containing ambiguous bases9. The remaining modified sequences were aligned to the SILVA reference database10. Chimeric sequences were removed using UCHIME. The remaining sequences were taxonomically classified using a naïve Bayesian classifier and the RDP training set v9, and clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs)11. METAGENassist was used to link OTU nomenclature to taxonomic assignments12.

The ABC trial was conducted with full IRB approval at all participating sites. All samples were processed in duplicate and characterized as sequence-positive, sequence-negative or inconclusive. A sequence-negative sample was one in which DNA was not amplified in either technical replica. To avoid accidentally sequencing rare contaminants, we conservatively considered samples to be negative if DNA amplification was not visible on an agarose gel. A sequence-positive sample was one in which DNA was amplified from both replicas, the replicas had a Euclidian distance score less than 0.3, and the dominant genus (>45% sequences per sample), if present, was the same in both replicas. Samples not meeting these criteria were deemed inconclusive and disregarded from further analysis (n= 12). For each sequence-positive sample, percent reads were calculated and replicates were then averaged for downstream analysis.

To display the average sequence abundances, a histogram was produced, color-coded by bacterial taxa. Euclidean distance was calculated between samples and the complete method was used for hierarchical clustering in the statistical package R v2.15.1. The resulting dendrogram was divided into 8 urotypes7. The rare urotypes were grouped into an “other” category, condensing the original 8 urotypes to a total of 5 urotypes for use in the analysis (Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, Gardnerella/Prevotella, Diverse, and Other) plus the negative category. These urotypes, along with the sequence-negative group, were then compared to participant demographics, symptoms at baseline and clinical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Differences were examined descriptively at baseline, as were changes in clinical outcome measures for individuals defined as sequence-positive and sequence-negative, as well as for individuals classified by urotype, further described below. The differences in binary baseline and outcome measures across these two categorical measures of sequence were examined via contingency tables, with p values generated from Chi-squared tests and differences in mean values for continuous measures evaluated using general linear models. Because all analyses were considered descriptive, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons and p values should be interpreted accordingly. To compare the mean abundance of the top 10 most abundant taxa, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3.

Results

Approximately half (51.1%, 93/182) the urine samples were sequence-positive. Table 1 displays demographics and baseline characteristics of participants relative to sequence status; the mean age was 58.5 years and most participants were white (77%). Sequence-positive subjects were younger (55.8 +/− 12.2 vs. 61.3 +/−9.0 years, p=0.0007), had a higher body mass index (33.7 +/− 7.3 vs. 30.1 +/− 6.6 kg/m2, p=0.0009) and had a higher mean number of baseline UUIE (5.7 +/− 2.5 vs. 4.2 +/− 2.1 per day, p<0.0001). Race, ethnicity, prior anticholinergic use, or study treatment assignment did not differ between sequence-positive and sequence-negative cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Sequence Status

| Characteristic | Overall | Sequence Positive | Sequence Negative |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, N | 182 | 93 | 89 | 0.0007 |

| Mean (SD) | 55.8 (12.2) | 61.3 (9.0) | ||

| Median (Min-Max) | 55.8 (31.1–85.4) | 61.2 (43.1–83.1) | ||

| Ethnicity, N (%) | 0.054 | |||

| Hispanic | 23 (25%) | 12 (13%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 70 (75%) | 77 (87%) | ||

| Race, N (%) | 0.15 | |||

| White | 68 (73%) | 73 (82%) | ||

| Non-White | 25 (27%) | 16 (18%) | ||

| BMI, N | 93 | 89 | 0.0009 | |

| Mean (SD) | 33.7 (7.3) | 30.1 (6.6) | ||

| Median (Min-Max) | 32.8 (20.5–52.4) | 28.8 (18.7–48.5) | ||

| Menopausal Status, N (%) | 0.059 | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 17 (20%) | 8 (9%) | ||

| Post-menopausal | 70 (80%) | 77 (91%) | ||

| Prior anticholinergic use, N (%) | 0.97 | |||

| Yes | 52 (56%) | 50 (26%) | ||

| No | 41 (44%) | 39 (44%) | ||

| Baseline Urgency Urinary Incontinence Episodes (UUIE) Stratum, N (%) | 0.0036 | |||

| 5 to 8 | 11 (12%) | 26 (29%) | ||

| 9+ | 82 (88%) | 63 (71%) | ||

| Baseline UUIE, N | 93 | 89 | <0.0001 | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.66 (2.5) | 4.20 (2.1) | ||

| Median (Min-Max) | 5.00 (1.7–12.0) | 3.67 (1.7–9.7) | ||

| OABq** Symptom Severity, N | 93 | 89 | 0.78 | |

| Mean (SD) | 68.1 (18.8) | 68.8 (18.5) | ||

| Median (Min-Max) | 70 (16.7–100) | 70 (26.7–100) | ||

| OABq** HRQL, N | 93 | 89 | 0.80 | |

| Mean (SD) | 45.6 (20.7) | 46.3 (24.0) | ||

| Median (Min-Max) | 47.7 (0–90.8) | 46.2 (6.2–98.5) | ||

| Treatment, N (%) | 0.47 | |||

| Active onabotulinumtoxin A | 42(45%) | 45 (51%) | ||

| Active anticholinergic medication | 51 (55%) | 44 (49%) |

p-value, testing sequence positive versus negative

OABq: Overactive Bladder quantitative

Sequence-positive subjects responded better to treatment with a larger decrease in baseline UUIE (−4.4 +/− 2.7 vs. -3.3 +/− 1.9, p=0.0013) with no evidence of interaction with treatment group (p=0.92). In both groups, sequence-positive subjects were less likely to develop UTI after initiation of study anti- incontinence treatment (9% vs. 27% post treatment UTI’s, p=0.0011) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes by Sequence Status

| Characteristic | Sequence Positive | Sequence Negative | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary tract infection, N (%) | 0.0011 | ||

| Yes | 8 (9%) | 24 (27%) | |

| No | 85 (91%) | 65 (73%) | |

| Change in UUIE, N | 90 | 89 | 0.0013 |

| Mean (SD) | −4.36 (2.7) | −3.32 (1.9) | |

| Median (Min-Max) | −4.03 (−11.7 – 0.7) | −3.17 (−9.3 – 2.5) | |

| OABq Symptom Severity Change, N | 90 | 89 | 0.37 |

| Mean (SD) | −46.8 (23.8) | −43.7 (22.7) | |

| Median (Min-Max) | −48.1 (−86.7 – 11.1) | −44.4 (−93.3 – 9.2) | |

| OABq HRQL Change, N | 90 | 89 | 0.60 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.2 (21.9) | 37.3 (25.2) | |

| Median (Min-Max) | 37.5 −9.0 – 96.7) | 36.9 (−28.8 – 93.8) |

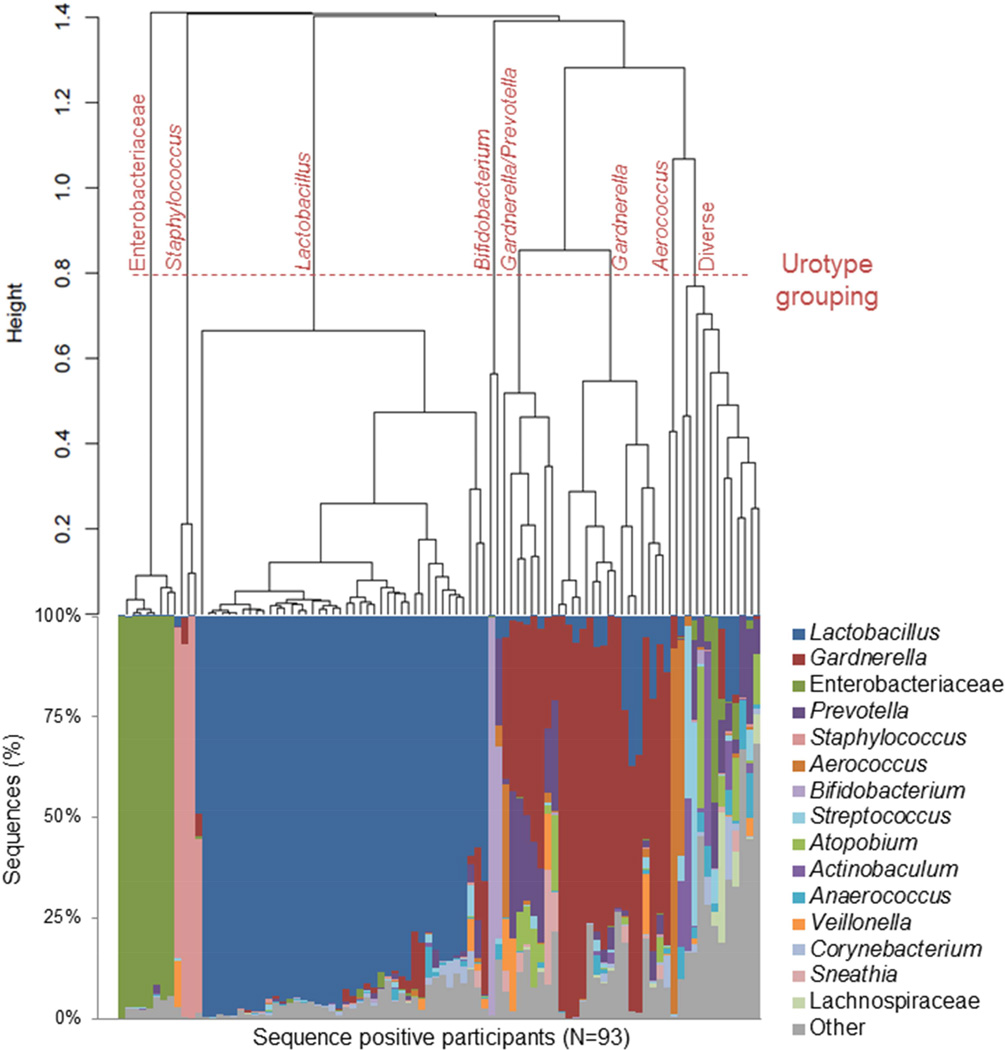

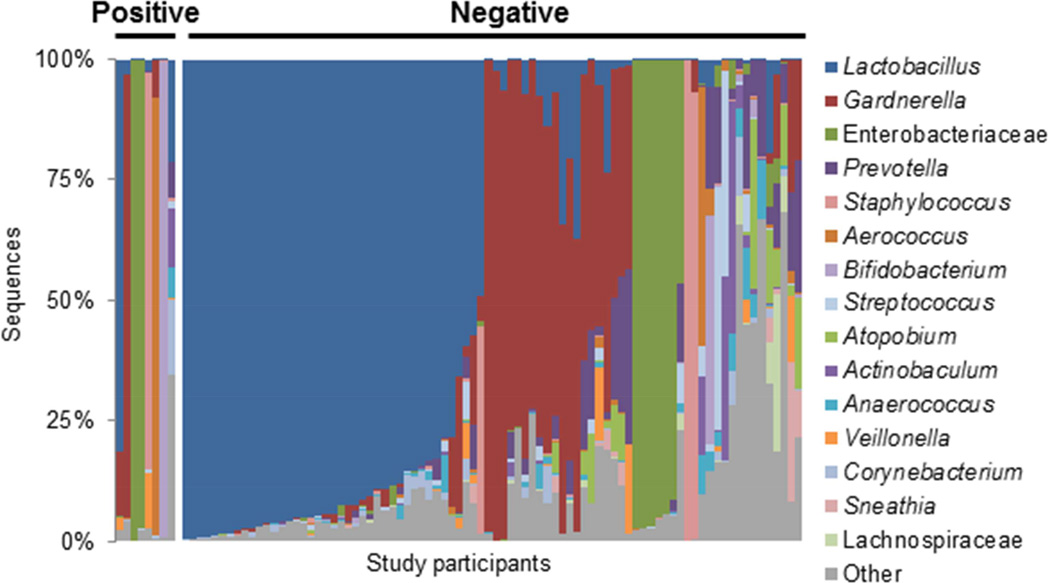

In sequence-positive urines, hierarchical clustering revealed eight major urotypes, as shown by the horizontal line (Figure 1, top). In seven of these urotypes, a single bacterial genus or family dominated (i.e., represented >45% total sequences in a sample) (Figure 1, bottom). For example, in the first urotype, Enterobacteriaceae accounted for >90% of the total sequences in all of the eight samples. Nearly half of the sequence positive urines were dominated by the genus Lactobacillus (45%), followed by Gardnerella (17%), Gardnerella/Prevotella (9%), Enterobacteriaceae (9%), Staphylococcus (3%), Aerococcus (2%) and Bifidobacterium (2%). The remaining cluster was labeled “Diverse” to signify those (13%) without a dominant genus. While these more diverse samples were often composed of different genera, they grouped together (Table 1, bottom). Each urotype was observed in samples from ≥2 performance sites and several urotypes were observed at multiple clinical sites (Table 3).

Figure 1. The urinary microbiota profile of sequence positive participants.

The urinary microbiota profiles of sequence positive participants cluster together, as demonstrated in the dendrogram (top), and by the dominant bacterial taxa present, as depicted in the histogram (bottom). The dendrogram was based on clustering of the Euclidean distance between urine samples and each line represents a separate individual. Urine samples that possessed the same dominant bacterial taxa grouped together in the dendrogram and were classified into the following urotypes, as shown by the dashed horizontal line: Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, Gardnerella/Prevotella, Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, Aerococcus and Diverse. The placement of the urotype grouping line provided clear distinction of urine samples by the dominant genera, while maintaining clusters that contain at least 2 urine samples. The histogram displays the bacterial taxa detected by sequencing as the percentage of sequences per urine by sequence positive participants (N=93). Each bar on the x-axis represents the urinary microbiota sequence-based composition of a single participant. The y-axis represents the percentage of sequences per participant with each color corresponding to a particular bacterial taxon. Bacteria were classified to the genus level with the exception of Enterobacteriaceae and Lachnospiraceae, which could only be classified to the family level. The 15 most sequence abundant bacterial taxa were displayed and the remainder of the taxa, including unclassified sequences, were grouped into the category “Other”.

Table 3.

Urotype distribution among collection locations. For each urotype, we verified that the samples came from at least two study sites, to rule out bias due to the collection location.

| Urotype | N | Site ID |

|---|---|---|

| Aerococcus | 2 | 08, 22 |

| Bifidobacterium | 2 | 02, 16 |

| Diverse | 12 | 02,07,15,17,18,21 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 8 | 02,06,07,17,18 |

| Gardnerella | 16 | 02,06,07,15,16,17,18,22 |

| Gardnerella/Prevotella | 8 | 02,07,08,18,22 |

| Lactobacillus | 42 | 02,06,07,14,15,16,17,18,21,22 |

| Staphylococcus | 3 | 02,17 |

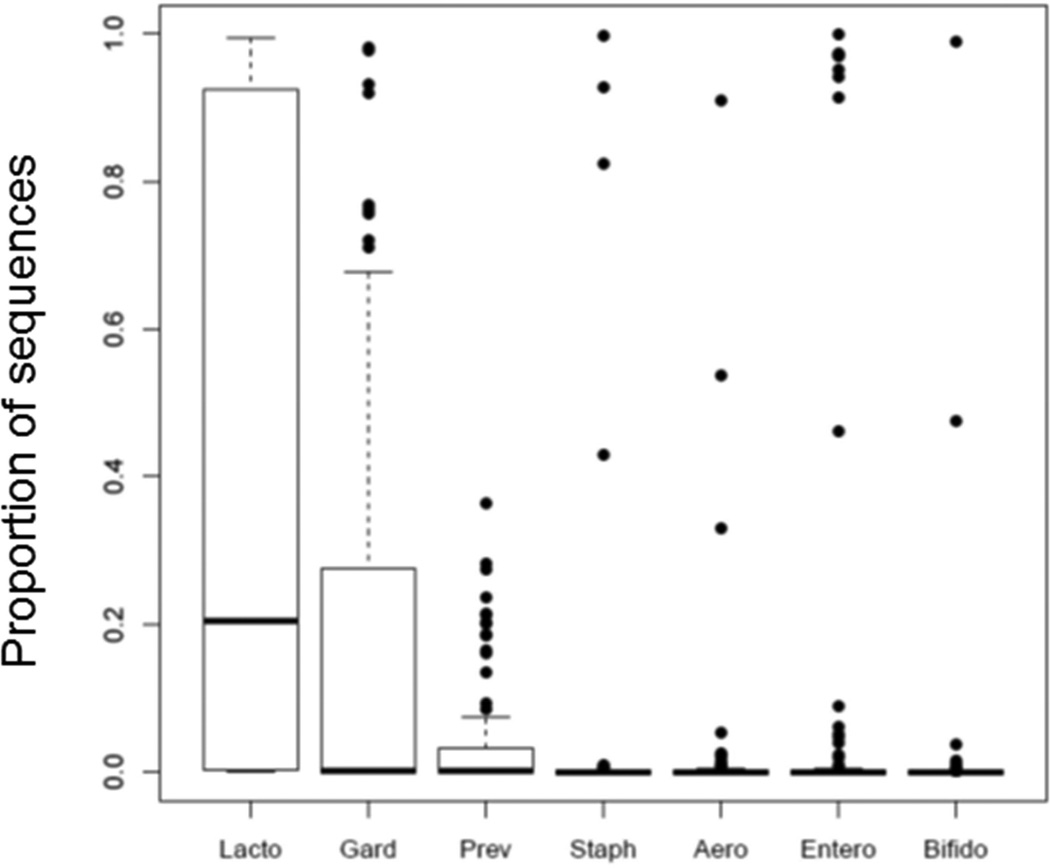

Most sequence-positive samples had a dominant genus (Figure 1). To assess the prevalence of these genera in samples where they did not dominate, we calculated the proportion of sequences belonging to the dominant taxon of each urotype across all sequence-positive samples. Figure 2 demonstrates that nearly all the sequence-positive samples contained Lactobacillus (with a median 20% Lactobacillus sequences per urine sample). With the exception of Gardnerella, the other urotype-defining taxa were less commonly detected in samples outside those they dominated.

Figure 2. Distribution of dominant taxa in urine of all sequence positive participants.

The sequence proportion of dominant taxa (taxa that accounted for greater than 45% of the sequences in at least one sample) were graphed for the sequence positive samples (N=93). The boxplots represent the 25th, 50th and 75th percentile of the sequence proportion, while points represent outliers. Lactobacillus was detected in the majority of urine samples and the sequence abundance ranged from 0 to 100% of the total sequences per sample. The median amount of Lactobacillus sequences detected per urine was 20%. Gardnerella was the second most frequently detected genus, with 43% of samples containing >1% Gardnerella sequences Whereas Staphylocccus, Aerococcus, Enterobacteriaceae and Bifidobacterium were detected in high abundance in a few samples, they were present at very low levels or not at all in the remainder of samples. For example, Staphylococcus and Aerococcus were detected at >45% of total sequences in only 3 and 2 samples, respectively. Lacto, Lactobacillus; Gard, Gardnerella; Prev, Prevotella; Staph, Staphylococcus; Aero, Aerococcus, Entero, Enterobacteriaceae, and Bifido, Bifidobacterium.

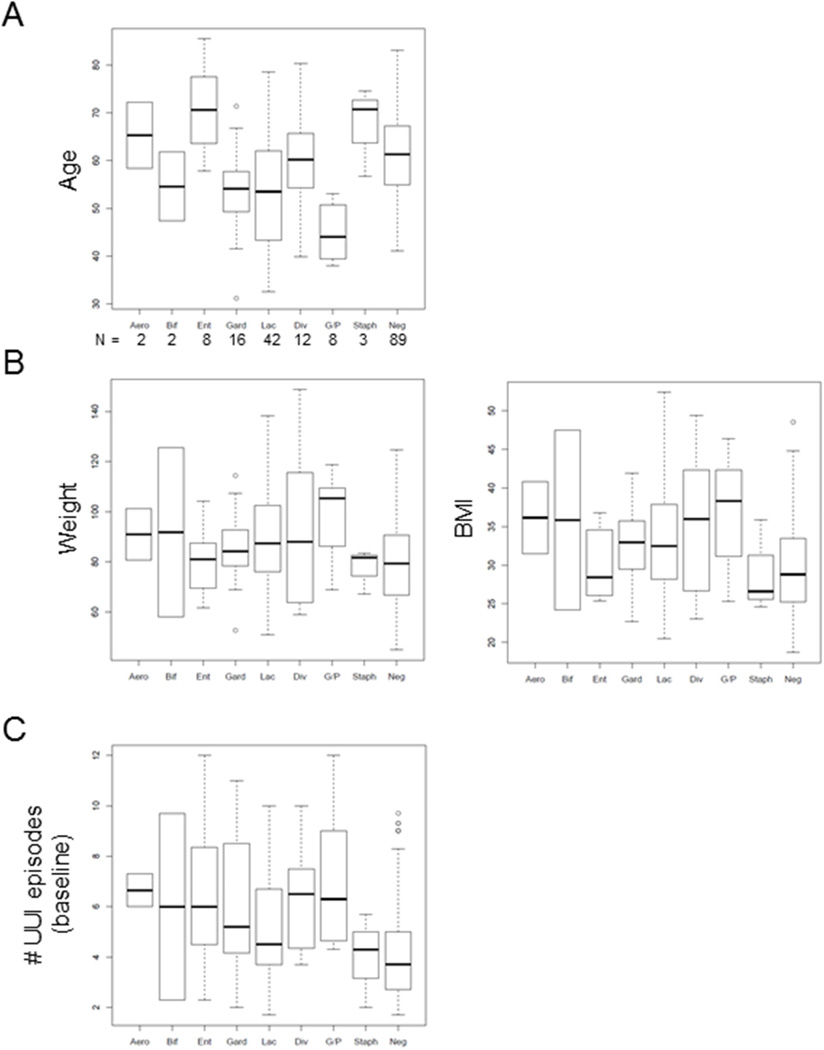

Cluster analysis (Figure 1) revealed eight major urotypes: Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, Gardnerella/Prevotella, Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, Aerococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Diverse. Although some major clusters (especially Lactobacillus, Gardnerella and Diverse) branched into sub-clusters, for further analyses, we treated these sub-clusters as one urotype. We also combined the less common urotypes (Gardnerella/Prevotella, Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, Aerococcus and Bifidobacterium) together (Other). We compared these five urotypes and the sequence-negative group to baseline demographic and clinical variables. Whereas race, ethnicity and menopausal status were similar across urotypes, age (p=0.005) and body mass index (p=0.014) differed (Table 4). Additional analysis detected an upward trend for age with the Enterobacteriaceae-dominant and Staphylococcus-dominant urotypes and a downward trend with the Gardnerella/Prevotella-dominant urotype (Figure 3A). Body mass index tended to be lower in the Enterobacteriaceae-dominant, Staphylococcus-dominant and sequence negative groups (Figure 3B). Whereas symptom severity was similar across urotypes, baseline UUIE differed by incontinence severity (p=0.046) and frequency (p<0.0001) (Table 4). While Staphylococcus-dominant and sequence-negative groups showed a trend towards lower baseline UUIE (Figure 3C), the number of urine samples representing these urotypes was small and the analysis lacked statistical power. Treatment response (change in UUIE, p=0.0017) and development of post-treatment UTI (p=0.0058) differed among the 5 urotypes (Table 5).

Table 4.

Baseline Characteristics as a Function of Urotype.

| Characteristic | Lactobacillus | Gardnerella | Diverse | Other | Negative | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.0005 |

| Mean (SD) | 53.2 (11.5) | 53.7 (10.0) | 61.0 (11.2) | 59.5 (14.0) | 61.3 (9.0) | |

| Median | 53.5 | 54.2 | 60.3 | 58.4 | 61.2 | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | 0.24 | |||||

| Hispanic | 10 (24%) | 5 (31%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (17%) | 12 (13%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 32 (76%) | 11 (69%) | 8 (67%) | 19 (83%) | 77 (87%) | |

| Race, N (%) | 0.20 | |||||

| Caucasian | 28 (67%) | 11 (69%) | 11 (92%) | 18 (78%) | 73 (82%) | |

| Non-Caucasian | 14 (33%) | 5 (31%) | 1 (8%) | 5 (22%) | 16 (18%) | |

| BMI, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.014 |

| Mean (SD) | 33.8 (7.6) | 32.6 (5.2) | 35.2 (8.7) | 33.3 (7.3) | 30.1 (6.6) | |

| Median | 32.5 | 32.5 | 36.0 | 32.8 | 28.8 | |

| Menopausal Status, N (%) | 0.22 | |||||

| Pre-menopausal | 10 (26%) | 4 (22%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (6%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Post-menopausal | 29 (74%) | 14 (78%) | 10 (83%) | 17 (94%) | 77 (91%) | |

| Prior anticholinergic use, N (%) | 0.71 | |||||

| Yes | 23 (55%) | 8 (50%) | 9 (75%) | 12 (52%) | 50 (56%) | |

| No | 19 (45%) | 8 (50%) | 3 (25%) | 11 (48%) | 39 (44%) | |

| Baseline UUIE Stratum, N (%) | 0.046 | |||||

| 5 to 8 | 6 (14%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) | 26(29%) | |

| 9+ | 36 (86%) | 14 (88%) | 12 (100%) | 20 (87%) | 63 (71%) | |

| Baseline UUIE, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.1) | 6.0 (2.8) | 6.2 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.9) | 4.2 (2.1) | |

| Median | 4.50 | 5.17 | 6.50 | 6.00 | 3.67 | |

| OABq Symptom Severity, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.49 |

| Mean (SD) | 65.2 (17.4) | 66.6 (19.1) | 69.2 (17.5) | 73.8 (21.4) | 68.8 (18.5) | |

| Median | 60.0 | 71.67 | 70.0 | 76.7 | 70.0 | |

| OABq HRQL, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.32 |

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (17.7) | 49.5 (21.2) | 42.9 (24.1) | 37.5 (22.5) | 46.3 (24.0) | |

| Median | 50.8 | 53.7 | 40.0 | 43.1 | 46.2 |

Figure 3. Demographic variable distribution by urotype, including the sequence-negative group.

Boxplots are shown comparing each urotype and the sequence negative group to A) age, B) weight, BMI and C) the number of UUI episodes at baseline for each participant. Aero=Aerococcus, Bif=Bifidobacterium, Ent=Enterobacteriaceae, Gard=Gardnerella, Lac=Lactobacillus, Div = diverse, G/P =Gardnerella/Prevotella, Staph=Staphylococcus and Neg = sequence-negative group. N stands for the number of samples within each group.

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes as a Function of Urotype.

| Characteristic | Lactobacillus | Gardnerella | Diverse | Other | Negative | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTI, N (%) | 0.0058 | |||||

| Yes | 1 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (9%) | 5 (22%) | 24 (27%) | |

| No | 41 (98%) | 15 (94%) | 11 (91%) | 18 (78%) | 65 (73% | |

| Change in UUIE, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.0017 |

| Mean (SD) | −3.8 (2.3) | −4.9(3.0) | −5.2(1.9) | −5.0(3.1) | −3.3(1.9) | |

| Median | −3.61 | −4.08 | −5.53 | −4.90 | −3.17 | |

| OABq Symptom Severity Change, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.50 |

| Mean (SD) | −42.7 (24.7) | −48.0 (25.2) | −51.8 (18.5) | −51.1 (24.2) | −43.7 (22.7) | |

| Median | −45.0 | −46.7 | −48.3 | −54.4 | −44.4 | |

| OABq HRQL Change, N | 42 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 89 | 0.38 |

| Mean (SD) | 35.2 (19.7) | 36.4 (28.6) | 48.5 (17.4) | 43.8 (21.3) | 37.3 (25.2) | |

| Median | 33.5 | 35.3 | 48.5 | 46.4 | 36.9 |

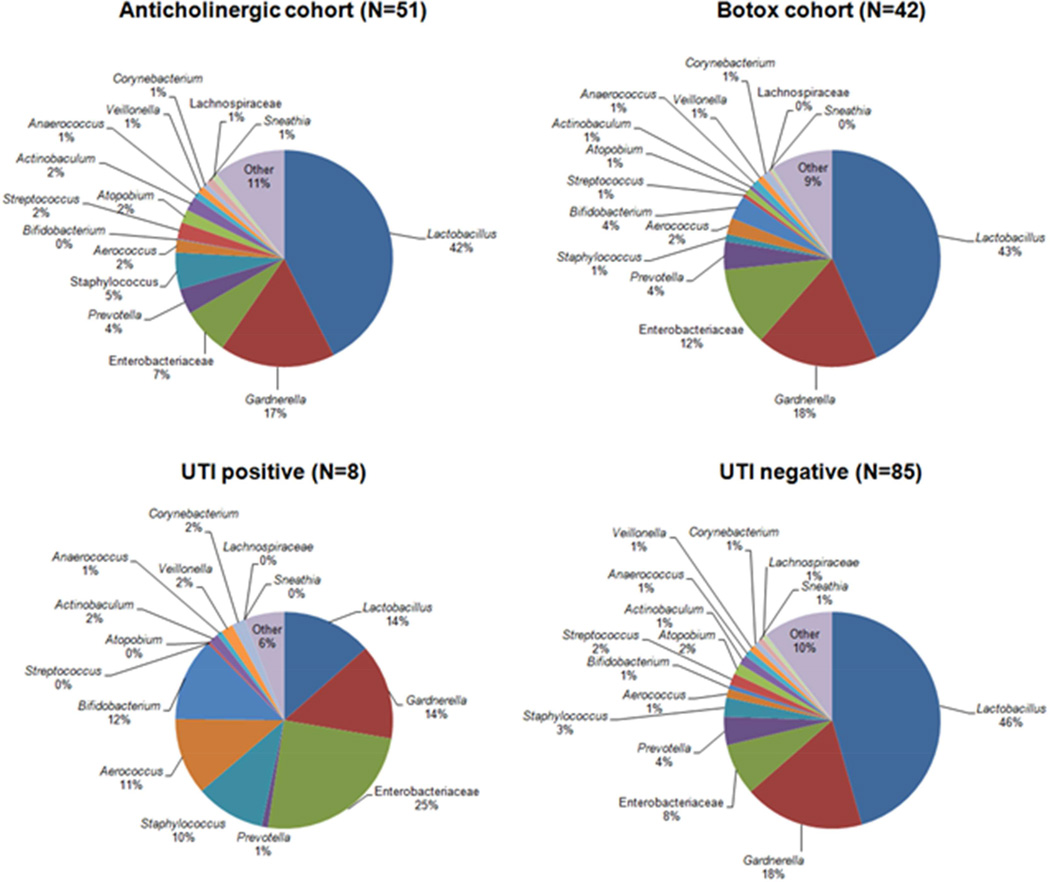

We compared the mean sequence abundance of sequence-positive participants by clinical variables. The two treatment cohorts (anticholinergic and onabotulinumtoxin A) displayed very similar mean sequence profiles at baseline, as predicted given randomized treatment assignment (Figure 4). However, the mean sequence profile of the sequence-positive women who developed a post-treatment UTI differed from those who did not develop a UTI. On average, sequence-positive women who developed a post-treatment UTI had fewer Lactobacillus sequences (14 vs. 46%, p=0.009) (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Comparison of average bacterial sequence abundance in urine by treatment group and UTI outcome.

The average amount of bacterial sequences detected in the sequence positive urine of each randomized treatment cohort (anticholinergic versus botox) and UTI outcome cohort (positive versus negative) was calculated. The average bacterial sequence abundance profiles were similar between treatment cohorts, whereas the profiles differed between UTI outcome cohorts.

Figure 5. Urinary microbiota profiles by UTI outcome.

The 15 most abundant bacteria detected by sequencing were displayed as the percentage of sequences per sample on the y-axis. The vertical bars along the x-axis represent the microbiota profile of individual participants separated by UTI outcome. The urinary microbiota profiles of the eight UTI positive participants consist of the following urotypes: 1 Lactobacillus, 1 Gardnerella, 2 Enterobacteriaceae, 1 Staphylococcus, 1 Aerococcus, 1 Bifidobacterium and 1 diverse. The proportion of Lactobacillus-dominant urines and diverse urines is less in the UTI positive group compared to the UTI negative group.

Comment

Principal findings of the study

In adult women with UUI, the composition of the urinary microbiota is identifiable, variable and related to certain clinical variables of potential importance. As the female urinary microbiota has only recently been detected3, 4, 6, 7, 13–15, an expanded perspective is warranted. The current study demonstrates that the status of the female urinary microbiota (sequence-positive or sequence-negative) can be used to sub-classify women with UUI and that sequence-positive women can be further sorted by composition into urotypes, based on the dominant bacterial genus or family or the lack thereof. The clinical utility of such sorting is yet to be established. However, the likelihood that UUI is a heterogeneous urinary disorder could make this new approach useful for patient phenotyping.

Meaning of the findings

Although the ABC study was designed prior to knowledge of the female urinary microbiota and our analysis was not based on an a priori hypothesis, the current findings add to the growing evidence that document the existence and define the characteristics of the female urinary microbiota3, 4, 6, 7, 13–15. Further study of the differences in biomass (sequence positive vs. sequence negative) and the microbial diversity by specific and dominant organisms is likely to advance our knowledge of UUI. The composition of the urinary microbiota and its clinical relationships also requires further study in other clinically relevant groups, including women undergoing surgery for prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence, and those without lower urinary tract symptoms.

Clinical Implications

To understand potential clinical relationships with the female urinary microbiota, studies of comparison populations are clearly needed, including asymptomatic women and those affected by non-UUI urinary symptoms. In an unrelated, smaller study, we compared the female urinary microbiota of adult women with and without UUI7. The results of this previous study closely align with those of the current one. Approximately half the samples were sequence-positive and most of those were dominated by one genus, with the Lactobacillus and Gardnerella urotypes most common. However, several species were strongly associated with UUI. These included emerging uropathogens (e.g., Aerococcus urinae), Gardnerella vaginalis, and Lactobacillus gasseri. In contrast, Lactobacillus crispatus was associated with women without lower urinary tract symptoms.

The bladder is an environment with low bacterial abundance, unlike the gut or the vagina. Although bacterial DNA was not sequenced from approximately half of our participants’ urine samples, it is possible that these sequence-negative bladders are not sterile, but rather contain bacteria at low difficult-to-sequence levels. The existence of this sequence-negative status is clinically important, as this group was at significantly greater risk for post-treatment UTI. This finding will require further study; it is possible that certain organisms, such as Lactobacillus, play an important regulatory or protective role to challenge the growth of common uropathogens, such as E. coli.

Research implications

Combined with the extreme sensitivity of PCR, caution is needed in low abundance environments to appropriately distinguish true members of the urinary microbiota from rare contaminants. Thus, we conservatively considered samples that amplified weakly to be sequence-negative to avoid over-interpretation of microbiota components. Even so, it is notable that the improved methods used in the current study reproducibly detected bacterial DNA in the urine of 56% of women in this population, compared to 39% in our previous analysis3.

DNA-based techniques are increasingly popular for microbiota study because they can detect bacteria without culture. Indeed, several groups have used 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis to detect the microbiota in the lower urinary tract of adult women and men4, 6, 7, 13, 15–18. Clinical reliance on standard urine cultures has limited our consideration of bacteria as etiological contributors to idiopathic lower urinary tract disorders, including UUI. This is because standard urine culture techniques underestimate the composition and diversity of bacteria, especially those that inhabit the lower urinary tract. Expanded urine culture techniques have been recently developed and shown to significantly outperform the standard techniques6, 14, but these new methods were developed after the samples in this study were obtained. Importantly, recent studies using our newly developed expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) method have documented that bacteria detected by 16S rRNA sequencing are alive and thus the sequencing is not simply detecting DNA of dead organisms6, 7.

Strengths and weaknesses

Some investigators may consider our analysis limited because our operational definition of “clinically free of UTI” used a negative dipstick, rather than require that they have a negative standard urine culture at baseline. Given the significant limitations of standard urine culture6, 7, 14, however, we do not consider this a major limitation for the ABC study or this analysis. Furthermore, few samples included uropathogens, typically detected by standard urine culture (e.g., E. coli) that could be indicative of a UTI. Given the nature of the index study, which was aimed at clinical treatment of affected patients, there is no age-matched control population without UUI symptoms in this randomized trial. As one of the first studies of the female urinary microbiota, it is underpowered to definitively assess differences in the distribution of the urinary microbiota by race or certain other variables.

Conclusion

Women with UUI are a heterogeneous population on the basis of their baseline urine bacterial sequence status and/or urotype. Nearly half of female trial participants with UUI, without evidence of clinical infection, had a urotype that was typically dominated by a single genus, most often Lactobacillus or Gardnerella. These bacterial communities appear to have clinical relationships with baseline UUI symptoms, response to treatment and risk for post-treatment UTI. As research in this area expands and incorporates samples from other clinically relevant populations, we fully anticipate further refinements in our understanding of the role of the female urinary microbiota in health and disease. Our findings suggest that previously undetected bacteria in the bladder of women may have a role in UUI, providing expanded opportunities for prevention and improved treatment approaches for UUI, such as modification of the microbiota to improve response to UUI treatments. Our findings also suggest that some bacteria may play a protective role in the bladder as they do in other human biological niches. The potential for such a protective role warrants further study.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was supported by grants from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, (Duke: 2-U10-HD04267-12, Loyola: U10-HD054136, UAB: 2-U10-HD041261-11, Utah: U10-HD041250, Cleveland Clinic: 2-U10-HD054215-06, UCSD: 2-U10-HD054214-06, Magee: 1-U10-HD069006-01, UTSW: 2-U10-HD054241-06, Univ. of Michigan: U10-HD41249, Brown University/Womens and Infants Hospital: U10 HD069013, New Mexico: U10 HD069025, Pennsylvania: U10 HD069010, RTI International: U01 HD069031RT: 1-U01-HD069010-01 and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health

We would like to acknowledge and thank the Loyola University Chicago Health Sciences Division’s Office of Informatics and Systems Development (which was developed through grant funds awarded by the Department of Health and Human Services as award number 1G20RR030939-0 1) for their expertise and for the computational resources utilized in support of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Holly E. RICHTER, Ph.D., M.D.- Leadership: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Board of Directors (no compensation); Health Publishing: Up-To-Date; Consultant: Pelvalon, Kimberly Clark; Meeting Lecturer: Symposia Medicus: Research Grants: Univ of CA/Pfizer, NIDDK, NICHD, NIAID, NIDDK/Yale, Pelvalon; Expert Review – Alabama Board of Medical Examiners

- Anthony Visco, MD – Scientific Study/Trial: Pelvic Floor Disorders Network

- Ingrid NYGAARD, M.D. – Health Publishing: Received an honorarium from Elsevier as Editor-in-Chief for AJOG.

- Matthew D. BARBER, M.D., M.H.S – Scientific Study/Trial: Grants from NICHD, grants from foundation for Female Health Awareness, other from Elsevier, other from UptoDate, outside the submitted work.

- Joseph Schaffer, MD – Health Publishing: McGraw-Hill Publishing – Royalties for six years; Meeting Participant/Lecturer: Astellas/GSK Pharmaceuticals; Scientific Study/Trial: Boston Scientific, Health Publishing: McGraw-Hill Publishing.

- Pamela Moalli, MD, PhD – Scientific Study/Trial: Independent Research Agreement with ACell.

- Rebecca ROGERS, MD – Health Publishing: McGraw Hill – Royalties from textbook.

- Alan J. WOLFE, Ph.D. – Scientific Study/Trial: Investigator Initiated Grant from Astellas Pharmaceutical for a study outside the submitted work.

- Linda BRUBAKER, MD – Scientific Study/Trial: Grants from NICHD (funding source for this study) and NIDDK during conduct of the study. Health Publishing: Personal fees from Up-To-Date.

- The following authors report no conflict of interest: Dr. Meghan M. Pearce, Dr. Michael Zilliox, Ms. Krystal Thomas-White, Dr. Charles Nager, Dr. Vivian Sung, Dr. Ariana Smith, Dr. Tracy Nolen, Dr. Dennis Wallace, Dr. Susan Meikle and Dr. Xiaowu Gai.

Trial Registration:

This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov under Registration #: NCT01166438.References

References

- 1.Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, Nygaard I, Paraiso MFR, Menefee SA, et al. Anticholinergic therapy vs. OnabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208872. 10/04; 2012/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brubaker L, Wolfe A. The new world of the urinary microbiome in women. Am J Obset Gynecol. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brubaker L, Nager CW, Richter HE, Visco A, Nygaard I, Barber MD, et al. Urinary bacteria in adult women with urgency urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2014 Sep;25(9):1179–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, Rong R, Kenton K, Fitzgerald M, et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2012 Apr;50(4):1376–1383. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05852-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, Nygaard I, Paraiso MF, Menefee SA, et al. Anticholinergic versus botulinum toxin A comparison trial for the treatment of bothersome urge urinary incontinence: ABC trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(1):184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Mueller ER, et al. Urine is not sterile: Use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014 Mar;52(3):871–876. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02876-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Thomas-White K, Fok C, et al. The female urinary microbiome: A comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. MBio. 2014 Jul 8;5(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01283-14. e01283-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan S, Cohen D, Ravel J, Abdo Z, Forney L. Evaluation of methods for the extraction and purification of DNA from the human microbiome. PLoS One. 2012;3:e33865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011 Aug 15;27(16):2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arndt D, Xia J, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Guo AC, Cruz JA, et al. METAGENassist: A comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jul 01;40(W1):W88–W95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouts DE, Pieper R, Szpakowski S, Pohl H, Knoblach S, Suh MJ, et al. Integrated next-generation sequencing of 16S rDNA and metaproteomics differentiate the healthy urine microbiome from asymptomatic bacteriuria in neuropathic bladder associated with spinal cord injury. J Transl Med. 2012 Aug 28;10 doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-174. 174,5876-10-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khasriya R, Sathiananthamoorthy S, Ismail S, Kelsey M, Wilson M, Rohn JL, et al. Spectrum of bacterial colonization associated with urothelial cells from patients with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. J Clin Microbiol. 2013 Jul;51(7):2054–2062. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03314-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nienhouse V, Gao X, Dong Q, Nelson DE, Toh E, McKinley K, et al. Interplay between bladder microbiota and urinary antimicrobial peptides: Mechanisms for human urinary tract infection risk and symptom severity. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 8;9(12):e114185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong Q, Nelson DE, Toh E, Diao L, Gao X, Fortenberry JD, et al. The microbial communities in male first catch urine are highly similar to those in paired urethral swab specimens. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson DE, Dong Q, Van Der Pol B, Toh E, Fan B, Katz BP, et al. Bacterial communities of the coronal sulcus and distal urethra of adolescent males. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson DE, Van Der Pol B, Dong Q, Revanna KV, Fan B, Easwaran S, et al. Characteristic male urine microbiomes associate with asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection. PLoS One. 2010 Nov 24;5(11):e14116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]