Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic conditions and limited access to healthcare experience stressful challenges due to the burden of managing both their conditions and their daily life demands. Resilience provides a mechanism of adapting to stressful experiences. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize the evidence about interventions to enhance resiliency in managing hypertension or type-2 diabetes in vulnerable populations, and to assess the efficacy of these interventions on clinical outcomes.

Methods

We searched multiple databases from early inception through February 2015 including randomized controlled trials that enrolled patients with type-2 diabetes or hypertension. All interventions that targeted resilience in vulnerable populations were included. Data were synthesized to describe the characteristics and efficacy of resilience interventions. We pooled the total effects by calculating standardized mean difference using the random-effects model.

Results

The final search yielded seventeen studies. All studies were conducted in the United States and generally targeted minority participants. Resiliency interventions used diverse strategies; discussion groups or workshops were the most common approach.

Conclusions

Interventions aimed at enhancing the resiliency of patients from vulnerable groups are diverse. Outcomes were not fully conclusive. There was some evidence that resilience interventions had a positive effect on HbA1c levels, but not blood pressure. The incorporation of resiliency-oriented interventions into the arsenal of prevention and management of chronic conditions appears to be an opportunity that remains to be better investigated and exploited, and there is need to pursue further understanding of the core components of any intervention that claims to enhance resilience.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence from the past 50 years of observational and interventional research show inconsistent results in effective management or improving adherence to treatment or outcomes of chronic conditions1. This finding suggests that interventions using a disease-centered approach might be insufficient, and that there is a need to look further into patient-centered processes that empower patients to deal with the demands of their chronic conditions2–4. Resilience –defined usually as an intrinsic mechanism of facing, managing or adapting to stressful experiences and maintain balance–is often recognized as an internal process that patients exploit to mobilize their coping abilities5. In recent years, resiliency-training programs have been developed to help patients improve their psychosocial wellbeing as a key factor to improving their overall health. Interventions oriented to enhancing patient’s resilience skills, especially amongst the most vulnerable populations, could help them manage their chronic condition through better adherence to prescribed medical regimens, achievement of control targets, and ultimately, improved health outcomes.

Hypertension and type-2 diabetes mellitus are highly prevalent cardiometabolic conditions that are associated with high mortality and morbidity when not treated or controlled properly6,7, especially in vulnerable populations8,9. In addition, poor adherence to drug treatment and lifestyle changes remain a challenge for health professionals such as cardiologists. It is necessary to find new ways of supporting patients’ efforts to follow physicians’ recommendations to manage their chronic conditions10. The management of hypertension and type-2 diabetes add new workload or demands to already existing daily life tasks10; this is a challenging process, especially for vulnerable populations, i.e. those who have limited healthcare resources or access to health services and/or low socioeconomic status11–14.

The concept of vulnerability has been widely used to explain health inequalities; however, it has not become an integral part of clinical practice. Conveying the constructs of resilience and vulnerability, both commonly used in the fields of psychology and social sciences, to a clinical audience can contribute towards improving the understanding of the broader context of the patients’ challenges and opportunities for bettering the care of chronic conditions. We conducted a systematic review of existing interventions aimed to introduce or enhance resilience in vulnerable populations with hypertension or type-2 diabetes. We hope our results will initiate a necessary discussion around the importance of recognizing the burden rising from chronic care management by taking into consideration patient-centered interventions.

METHODS

This review followed the recommended PRISMA guidelines15. The analytic framework of this systematic review is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analytic Framework

Definition of vulnerable populations

Vulnerable populations were defined as social groups with an increased relative risk of or susceptibility of suffering adverse health outcomes, having reduced probabilities of receiving timely and quality care for their chronic conditions, or those who have less opportunities to put into practice the treatment and recommendations suggested to them regarding the management of their chronic condition16. We included ethnic minorities as vulnerable populations, along with those of low socioeconomic status or living within a limited-resources setting, as these have been identified widely as fundamental causes of increased susceptibility or vulnerability to disease conditions and/or with socioeconomic obstacles to receiving appropriate and timely health care17,18.

Interventions targeting resilience

There is a lack of consensus about any single theoretical framework to guide the development or application of programs to enhance resilience19. Thus, when selecting interventions for this review, we included any intervention that used similar or related constructs, including hardiness, challenge, coping, stress management or depression management, self-efficacy and problem-solving for vulnerable individuals with hypertension and type-2 diabetes (See Table 1). We did not exclude studies that had resiliency training as only one part of the intervention; neither did we exclude those that did not use the term “resiliency training”. We also included self-management interventions that had a component targeted at improving the patient’s psychosocial wellbeing. Because resiliency training is different from self-management support, we excluded studies that focused solely on education of self-management without consideration to resiliency constructs.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

| Topic | Population | Study type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion |

|

Vulnerable populations:

|

Randomized control trials Quasi-experimental studies |

| Exclusion | Exclusively related to self-management or adherence to drugs or lifestyles. | Elderly, Women (if that is the only characteristic that refers to their vulnerability). | Review articles Letters Editorials Systemic review |

Literature search and study eligibility

We conducted a literature search regarding any intervention used to introduce, train, teach or enhance resilience in vulnerable population to manage hypertension and/or type-2 diabetes or its complications. We included randomized controlled trials that enrolled vulnerable individuals diagnosed with or taking medications for hypertension and/or type-2 diabetes. We did not limit our search to any type of comparator. We expanded our search to include all languages, and searched selected databases from inception through February 2015 as the latest date of inclusion.

A comprehensive literature search was constructed (Appendix 1 in Online Supplement) and conducted by an expert reference librarian with input from study investigators (AMAD, JJM). Our search included the electronic databases MEDLINE™, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, and Scopus, using various combinations of controlled vocabulary supplemented with key words to search for constructs related to interventions aiming to deal with resilience in vulnerable population. Six reviewers worked in duplicate and independently (ML, MAP, GS, MC, GV and JA), identified quasi-experimental and randomized trial studies eligible for further review by screening abstracts and titles. If a study was deemed relevant, the article was obtained and then reviewed in full text for further thorough duplicate and independent assessment (MAP/GM, ML/JJM). Manual cross-referencing for possible studies was conducted, and duplicates were excluded. Discrepancies were adjudicated by a third party (ABO, MAP or ML) or by consensus. Studies not reporting outcomes within the a priori domains or not reporting them at the level of the randomized participants (e.g. reporting changes in team or group culture as measured in different post-intervention samples) were not included in the meta-analysis.

Data Extraction

Data extraction from each study was done in duplicate by two co-authors (ML and MAP). They extracted data on patient demographics, study baseline characteristics, study design variables, study aim, sample size, intervention and comparator types and characteristics, definition of resilience, and reported clinical outcome measures for each study. We also extracted variables related to patient-oriented outcomes that included self-empowerment, increased coping resources, personal strain, stress management, acceptance, mindfulness, depression, self-efficacy, reduction of social stressors, problem solving, quality of life, diabetes distress.

Quality Assessment

To appraise the risk of bias (study quality), we used the Cochrane Collaboration recommended criteria in assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials20. A summary of the risk of bias within each study (ABO, ML) is summarized in Appendix 2 in Online Supplement.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest included measuring and characterizing interventions targeting resilience and their effect on clinical outcomes, e.g. changes in blood pressure or changes in HbA1c.

Statistical analysis

For the quantitative analysis, we extracted data regarding sample size, HbA1c means and standard deviation (SD) at the longest follow-up period reported in each trial. We also extracted data for SBP means although this information was not used for meta-analysis.

We pooled the total effects across different interventions assessing the same or similar constructs of resilience by calculating standardized mean difference (SMD) between intervention and control/other intervention groups. We pooled data by the inverse variance method in random effect meta-analysis (DerSimonian and Laird random-effect models21). To measure the overall heterogeneity across the included studies, we used I2 statistic, where I2 >50% suggests high heterogeneity.

Pre-specified subgroups included the type of control group used (usual care or other intervention that may or may not involve resilience components). The purpose of this subgroup analysis was to determine a difference in the effect according to study characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 13.0 for Windows (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, US).

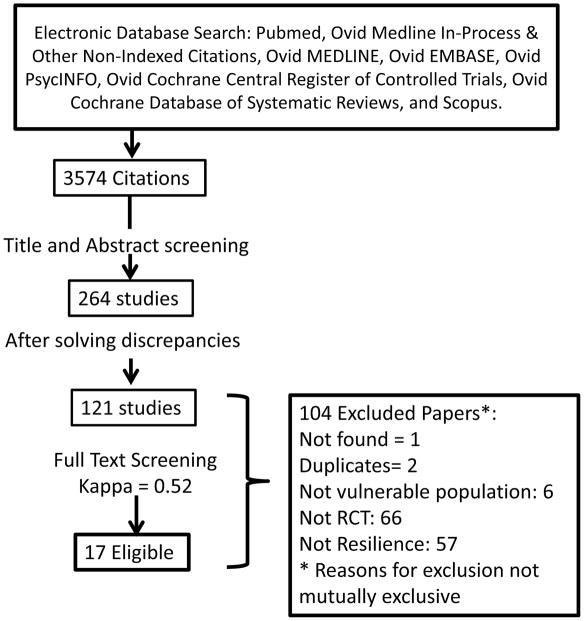

RESULTS

The initial search identified 3,574 citations and after abstracts and full text screening, only 17 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram

The risk of bias was moderate to high, mainly due to lack of clarity of methodological approach to address blinding, randomization, and selective outcomes reporting as summarized in Appendix 2.

Study characteristics

Seventeen intervention studies were included in the review; all studies described interventions deployed in the US. None of the studies focused on diabetes complications. Of the seventeen selected studies, sixteen were RCTs3,22–36 and one was a pre-post study37. Five studies were pilot/feasibility studies29,31,32,36,37. Three studies targeted patients with hypertension27,28,36, thirteen described interventions in patients with diabetes3,22–26,29,30,32–35,37, and one study targeted patients with both conditions31 (Online Table S1).

There was a wide variety of number of participants in each intervention. Seven3,22,29–32,36 out of seventeen studies had one hundred or fewer participants (Online Table S2).

All but two studies28,30 were aimed at low-income participants. These two studies targeted Korean Americans who had recently migrated to the US. Most of the interventions targeted an ethnic minority in the US. Seven22–24,26,32,34,37 targeted Latinos—referred to as Hispanic, Latino, Mexican Americans or Spanish speaking, three interventions targeted African Americans29,31,36, and one targeted “ethnic minorities”, mostly Latinos and Chinese Americans33. Four described their population as “low income” but upon closer scrutiny ethnic minorities represented more than 50% of the participants3,25,27,35.

Characteristics of interventions addressing resilience

Interventions were very heterogeneous in terms of the constructs of resilience they used. The most common constructs were: promoting self-empowerment22, enhancing self-confidence or self-esteem30,36, providing skills to manage concerns and feelings about the impact of the illness on their life23, providing skills managing problems and formulating their own solutions23,26,31,32,35, helping patients manage competing life priorities29, developing acceptance and mindfulness3, becoming more assertive in the patient-clinician interaction25, and improving their emotional health through stress-management25,28,36. Four studies included the promotion of psychosocial wellbeing as part of the self-management program22,31,33,34. None of the studies used the same approach to define the construct of resiliency, yielding a variety of surrogate or proxies of resiliency.

Interventions used different strategies to achieve their goals related to resiliency enhancement. Most studies used discussion sessions (or workshops) with various frequencies and lengths3,22–25,27,29–32,34,36 (Online Table S2), five studies used peer support or lay leaders to help patients cope with their chronic condition22,31,34,35,37, two provided telephone counselling28,37. Two interventions used telephone calls for follow-up of the educational sessions31,35 and another one used it for providing self-management support33. One intervention included family members for social support24.

Use of cultural competence

Only two interventions mentioned the concept of cultural competence in the background section23,30. Kim et al. (2009) justified the use of cultural competence by stating that “researchers have found that currently available interventions for ethnic minority groups with diabetes type 2 are largely inadequate and ineffective because of insufficient integration of cultural framework and tailored strategies, which often results in suboptimal outcomes”30. Brown et al. (2005) operationalized cultural competence as “employing the preferred language, integrating cultural dietary preferences, emphasizing social activities and family participation, and holding open nonjudgmental discussions of cultural health beliefs and practices”23.

Elements of cultural competence were present in five other studies: Lynch (2014)31 culturally-tailored nutrition education for an African American population; Rosal et al. (2005)32 tailored the intervention to the literacy needs of Hispanics and used culturally familiar experiences to deliver the intervention (soap operas). Glasgow et al. (2013)27 reported designing a culturally and literacy appropriate intervention by using fourth grade reading level and Latino and African American recipe books; and Brown et al.’s (2013)24 intervention was tailored to Mexican Americans “in terms of language, dietary recommendations, social emphasis, family participation, and incorporation of cultural health beliefs”. Horton et al. (2007)37 described that they took into account characteristics of Hispanics to develop the intervention such as the reluctance of Hispanics “to place their own health needs above those of their family”. Horton et al. (2007)37 also clarified that the peer support model they used had been shown to be acceptable to this population. Thom et al. (2013)35 and Hill-Bridges et al. (2011)29 used –if/when necessary–the mother tongue of the participants to ensure the appropriateness of their intervention.

Effect on hypertension control

None of the three studies that aimed at reducing blood pressure through resilience enhancement recorded improvements in blood pressure control. Interventions in these studies varied widely, e.g. counseling28, internet-based educational sessions27, and cognitive mediation training36. Given the small number of studies and lack of reported effects, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

Effect on diabetes control

Of the fourteen studies that aimed at diabetes control through resilience enhancement, six reported improvements in HbA1c when comparing the intervention vs. the control group3,29–32,35. Four reported no impact22,26,33,34, and four reported improvements when comparing baseline measurements against follow-up measurements in the intervention group23–25,37. Interventions in these studies varied widely, however, heterogeneity was not observed (I2 = 0%, p-value = 0.62) and meta-analysis was pursued (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest Plot

Meta-analysis: Effect on HbA1c

Only seven studies had more than three months of follow-up and reported HbA1c means and SD. Pooled effects are shown in Figure 3, indicating a reduction (non standardized) in HbA1c of −0.43 (95% CI −0.68; −0.17).

When compared to usual care, the interventions aimed at resilience were associated with statistically-significant improvements in HbA1c levels (pooled SMD −0.18; 95% CI −0.31 to −0.06; I2 = 0.8%). Resilience interventions showed a trend towards improvement in HbA1c when compared to other interventions, though this was not statistically significant (pooled SMD −0.14; 95% CI −0.29 to 0.01; I2 = 0.0%) as shown in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

In this systematic review we found diverse and inconsistent evidence about the effect of interventions benefiting resilience in diabetes and hypertension management in vulnerable populations. Interventions aimed at enhancing resilience (constructs) significantly improved HbA1c levels in patients with type-2 diabetes when compared to usual care, but there was no comparable effect when compared to other interventions. Discussion groups or workshops were the most common intervention tested. Resilience was addressed through different constructs such as enhancing capacity or ability to manage stress, self-empowering, problem solving or mental health. The wide variety of strategies made it impossible for us to assess a set of common characteristics for successful interventions, however cultural competence was a recurring component of most of the interventions analyzed. Therefore, the design, evaluation and incorporation of resiliency-oriented interventions into the arsenal of prevention and management of chronic conditions appear to be a challenging opportunity that remains to be sufficiently investigated.

Comparison with existing literature

Five recent systematic reviews have focused on resiliency and/or interventions targeting at vulnerable populations with a chronic condition19,38–41. Two reviews assessed interventions aimed at improving some aspect of chronic diseases management in ethnic minorities40,41. Wilson et al. found that access to healthcare is hindered by healthcare providers’ limited awareness of the cultural practices and beliefs of patients41. Our review points to the relevance of including a cultural competence approach when working with minority populations. Although none of the studies we reviewed provided information about training clinicians on cultural competence, such training has been identified as an important competency for provision of chronic care42.

Similar to our findings on clinical outcomes for type-2 diabetes, Attridge et al.’s review found short to medium-term effects on glycemic control through delivering culturally appropriate health education interventions for ethnic minorities with type-2 diabetes. These authors argue that public health measures tend to be decided by health professionals, with little or no reference to the needs of minority communities40. Cultural competent resiliency training could provide an avenue to improve the health status of the vulnerable groups we seek to serve. Clear homogeneous definitions of both resiliency and resiliency training are not yet available, posing an important challenge. A recent meta-analysis by Leppin et al. to evaluate the efficacy of resiliency training programs targeted at patients with chronic conditions concluded that it is necessary to better define the resilience construct19. This lack of a standard definition of resiliency is consistent with our findings and with Windel’s43 review on resilience measurement scales.

In order to overcome the difficulty of not having a single consistent definition of resiliency, Cal et al. conducted a systematic review of resiliency and chronic conditions excluding interventions that did not use a resilience scale. The authors found an inverse correlation between resiliency scores and the progression of chronic diseases, suggesting that resilience may influence the process of illness and health outcome38.

Finally, Walton-Moss et al. conducted a systematic review of community-based cardiovascular health interventions in vulnerable populations39 and found that behavioral change interventions, such as those targeting physical activity or smoking, were challenging to implement and those aiming at reducing blood pressure were the most promising. In comparison with Walton-Moss’s review, our study expands into exploring the impact of resilience-focused interventions for vulnerable populations in two major chronic conditions: diabetes and hypertension.

Main challenges in researching resilience in vulnerable populations

While there is evidence about benefit in clinical outcomes from resiliency training efforts such as improving stress and mental wellness44, this evidence, in accordance with our findings, showed a paucity of rigorous and clear head-to-head comparisons of interventions specifically targeting resilience. Thus, there is a strong need to improve understanding of the core components of any intervention that claims to enhance resilience. Despite some indications that improving resilience is likely to yield major benefits, especially in the care of people with chronic conditions, there is no harmonization or clear guidance on what aspect of resilience should be acted upon.

Enhancing resilience aims to take into consideration the values patients hold, their cultural practices, the challenges they face, and the demands they shoulder. In so doing, it is assumed that patients’ capacity and abilities to manage their conditions will be improved, thus adding towards a broader goal of delivering the best care possible. The results of our review suggest that clinicians ought to be involved in the effort towards researching resilience-oriented interventions, as well as improving understanding of their patient’s social context and cultural values.

We acknowledge that the concept of vulnerability, and henceforth of vulnerable populations, requires major clarifications of successful interventions, including where and among whom and under which circumstances these interventions should be applied, especially in terms of chronic conditions. A resilience-enhancing intervention, given its strong cultural grounding, may differ if it targets low-income Asian population living in their country of origin from one oriented to a different ethnic group that experience, for example, international migration. These concepts, of namely how best to characterize resilience (the what) and how best to target groups in need (the whom) require careful thought to avoid a one-size fits all type of approach. In the same vein, an approach that targets resilience in larger populations, be it vulnerable or not, opens exciting avenues to explore new opportunities that are particularly important considering the huge demand to address unmet needs in cardiac care and chronic non-communicable diseases at the global level45,46.

Limitations

There was heterogeneity in the interventions (type and framework) delivered as well as the characteristics of the population at which they were aimed. Additionally, resilience definitions varied and therefore relied on the authors’ description. The small number of participants as well as the presence of pilot studies with short follow-up made it difficult to assess the success of the interventions described and limited their generalizability. However, our study included the best available evidence, strengthened by the inclusion of randomized controlled trials, rigorous methodological approach, the expansive and comprehensive literature search, the inclusion of all publication languages, and selecting studies in duplicate. Additionally, and to our knowledge, our review provides the best available evidence of the effect of such measures within this type of population, providing direction and rationale for future research.

Recommendations

Our review highlights existing challenges for current clinical training in cardiology and practice with vulnerable populations. It signals the importance of moving away from a disease-centered approach towards an incorporation of patient-centered processes aimed at empowering patients to deal with the demands of their conditions in context-relevant and culturally appropriate ways.

Given the diversity of studies and strategies to promote resilience it is not possible to state the minimum characteristics in terms of length, frequency, format or setting in which such interventions ought to occur in order to have positive clinical outcomes. However, it seems that cultural competence is an important factor in such interventions.

The quality of evidence is low mainly due to imprecision (various samples sizes and wide intervals), indirectness (difference in interventions and outcomes) and inconsistency (varied size effects and point estimates). Despite the diverse and inconsistent evidence about the effect of interventions benefiting resilience in hypertension and diabetes management in vulnerable populations, we found that interventions aimed to enhance (some constructs of) resilience significantly improved HbA1c levels in patients with type-2 diabetes. Given the similarities in terms of the demands that the healthcare management of chronic conditions impose to patients, and considering that many of these conditions occur concomitantly instead of in isolation, we anticipate that findings in the field of type-2 diabetes can well inform practice in other areas of clinical cardiology.

We believe that any intervention that aims at helping patients from vulnerable groups manage their chronic condition must include a well-defined resiliency component. This will ensure that suggestions made by clinicians are realistic, sensitive and respectful of patient’s specific needs. This review has shown how resilience and vulnerability are not alien for cardiac care and chronic diseases. Indeed, addressing them can open pragmatic paths to ensure adequate design of interventions with a special emphasis on implementation science, with the common goal of improving overall health.

Supplementary Material

e-Table 1. Summary of included studies characteristics

e-Table 2. Characteristics of interventions and comparators

Acknowledgments

To various members of the CRONICAS Centre of Excellence in Chronic Diseases at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia who provided advice throughout different phases of the process, especially Francisco Diez-Canseco. Additionally, our team is extremely grateful to the support provided by Patricia J Erwin, PLS and Victor Montori, MD at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, U.S.A.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

MAP, ML, ABO, GM and JJM are with the CRONICAS Centre of Excellence in Chronic Diseases at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract No. HHSN268200900033C. MAP is supported by a Post Doctoral Fellowship from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONCYTEC). ML is supported by Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health (R21TW009982). Antonio Bernabe-Ortiz is a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellow in Public Health and Tropical Medicine (103994/Z/14/Z). JJM is supported by Fogarty International Centre (R21TW009982), Grand Challenges Canada (0335-04), International Development Research Center Canada (106887-001), Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research (IAI CRN3036), Medical Research Council UK (M007405), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (U01HL114180), National Institutes of Mental Health (U19MH098780). The funders had no role in decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Absetz P, Haukkala A, Uutela A. Socioeconomic status and psychosocial mechanisms of lifestyle change in a type 2 diabetes prevention trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38:160–5. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregg J, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:336–43. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561–87. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradshaw BG, Richardson GE, Kumpfer K, et al. Determining the efficacy of a resiliency training approach in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:650–9. doi: 10.1177/0145721707303809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albers JW, Herman WH, Pop-Busui R, et al. Effect of prior intensive insulin treatment during the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) on peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes during the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1090–6. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) Jama. 2014;311:507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Guidelines for Primary Health Care in Low Resource Settings. Geneva: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendis S, Lindholm LH, Mancia G, et al. World Health Organization (WHO) and International Society of Hypertension (ISH) risk prediction charts: assessment of cardiovascular risk for prevention and control of cardiovascular disease in low and middle-income countries. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1578–82. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282861fd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May CR, Eton DT, Boehmer K, et al. Rethinking the patient: using Burden of Treatment Theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:281. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eton DT, Ridgeway JL, Egginton JS, et al. Finalizing a measurement framework for the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:117–26. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S78955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM, Mair FS. Understanding patients’ experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:235–43. doi: 10.1370/afm.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinhardt MA, Mamerow MM, Brown SA, Jolly CA. A resilience intervention in African American adults with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study of efficacy. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:274–84. doi: 10.1177/0145721708329698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:1041–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edward K. Chronic illness and wellbeing: using nursing practice to foster resillence as resistance. Br J Nurs. 2013;22:741–2. 4, 6. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.13.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanstone M, Giacomini M, Smith A, Brundisini F, DeJean D, Winsor S. How diet modification challenges are magnified in vulnerable or marginalized people with diabetes and heart disease: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13:1–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan AM, Gee GC, Laflamme DF. The Association between self-reported discrimination, physical health and blood pressure: findings from African Americans, Black immigrants, and Latino immigrants in New Hampshire. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17:116–32. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leppin AL, Bora PR, Tilburt JC, et al. The Efficacy of Resiliency Training Programs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. PLoS Med. :9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111420. 2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins PT, Altman DG, Gotzsche P, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ Open. 2011:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baig AA, Giese A, Locklin CA, et al. Picture good health: A church-based, photovoice intervention for latinos with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med; Conference: 36th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, SGIM 2013 Denver, CO United States. Conference Start: 20130424 Conference End: 20130427. Conference Publication: (var.pagings); 2013. pp. S148–S9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown S, Blozis SA, Kouzekanani K, Garcia AA, Winchell M, Hanis CL. Dosage effects of diabetes self-management education for Mexican Americans: the Starr County Border Health Initiative. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:527–32. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown S, Kouzekanani K, Garcia AA, Orlander PR, Hanis CL. Diabetes self-management and leptin in Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes: the Starr County border health initiative. Diabetes Educator. 2013;39:820–7. doi: 10.1177/0145721713505153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daly KD. Test of a culturally sensitive health empowerment intervention on stress, health promoting behaviors, blood glucose and blood pressure among diverse adults with type 2 diabetes from low-income households. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2012;73:3290. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:706–13. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Askew S, Purcell P, et al. Use of RE-AIM to address health inequities: Application in a low-income community health center-based weight loss and hypertension self-management program. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2013;3 (2):200–10. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0201-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han H-R, Kim J, Kim KB, et al. Implementation and success of nurse telephone counseling in linguistically isolated Korean American patients with high blood pressure. Patient Education & Counseling. 2010;80:130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill-Briggs F, Lazo M, Peyrot M, et al. Effect of problem-solving-based diabetes self-management training on diabetes control in a low income patient sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:972–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1689-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim M, Han H-R, Song H-J, et al. A community-based, culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 2009;35:986–94. doi: 10.1177/0145721709345774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch EB, Liebman R, Ventrelle J, Avery EF, Richardson D. A self-management intervention for African Americans with comorbid diabetes and hypertension: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;11:130349. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosal M, Olendzki B, Reed GW, Gumieniak O, Scavron J, Ockene I. Diabetes self-management among low-income Spanish-speaking patients: a pilot study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29:225–35. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2903_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schillinger D, Handley M, Wang F, Hammer H. Effects of self-management support on structure, process, and outcomes among vulnerable patients with diabetes: a three-arm practical clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:559–66. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang TS, Funnell M, Sinco B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of peer leaders and community health workers in diabetes selfmanagement support: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37 (6):1525–34. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghorob A, Hessler D, De Vore D, Chen E, Bodenheimer TA. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:137–44. doi: 10.1370/afm.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb M, Beckstead J, Meininger J, Robinson S. Stress management for African American women with elevated blood pressure: a pilot study. Biological Research for Nursing. 2006;7:187–96. doi: 10.1177/1099800405283144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horton C, Flores C. Advancing diabetes self-management in the Mexican American population: a community health worker model in a primary care setting. Diabetes Educator. 2007;33 (Suppl 6):159S–65S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cal SF, Ribeiro de Sa L, Glustak ME, Barreto Santiago M. Resilience in chronic diseases: A systematic review. Cogent Psychology. 2015:2. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walton-Moss B, Samuel L, Nguyen TH, Commodore-Mensah Y, Hayat MJ, Szanton SL. Community-based cardiovascular health interventions in vulnerable populations: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29:293–307. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31828e2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attridge M, Creamer J, Ramsden M, Cannings-John R, Hawthorne K. Culturally appropriate health education for people in ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD006424. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006424.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson C, Alam R, Latif S, Knighting K, Williamson S, Beaver K. Patient access to healthcare services and optimisation of self-management for ethnic minority populations living with diabetes: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fouche C, Kenealy T, Mace J, Shaw J. Practitioner perspectives from seven health professional groups on core competencies in the context of chronic care. J Interprof Care. 2014;28:534–40. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.915514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Windle G, Bennet K, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011 Feb;:9–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:357–68. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, Feigl AB, Gaziano T, Mowafi M, Pandya A, Prettner K, Rosenberg L, Seligman B, Stein A, Weinstein C. The Global Economic Burden of Non-communicable Diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

e-Table 1. Summary of included studies characteristics

e-Table 2. Characteristics of interventions and comparators