Abstract

Background

Breast and cervical cancers have emerged as major global health challenges and disproportionately lead to excess morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) when compared to high-income countries. The objective of this paper was to highlight key findings, recommendations, and gaps in research and practice identified through a scoping study of recent reviews in breast and cervical cancer in LMICs.

Methods

We conducted a scoping study based on the six-stage framework of Arskey and O’Malley. We searched PubMed, Cochrane Reviews, and CINAHL with the following inclusion criteria: 1) published between 2005-February 2015, 2) focused on breast or cervical cancer 3) focused on LMIC, 4) review article, and 5) published in English.

Results

Through our systematic search, 63 out of the 94 identified cervical cancer reviews met our selection criteria and 36 of the 54 in breast cancer. Cervical cancer reviews were more likely to focus upon prevention and screening, while breast cancer reviews were more likely to focus upon treatment and survivorship. Few of the breast cancer reviews referenced research and data from LMICs themselves; cervical cancer reviews were more likely to do so. Most reviews did not include elements of the PRISMA checklist.

Conclusion

Overall, a limited evidence base supports breast and cervical cancer control in LMICs. Further breast and cervical cancer prevention and control studies are necessary in LMICs.

Introduction

As a global health priority, cancer is rapidly emerging as a visible and prevalent challenge differentially impacting low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared with high-income countries (HICs) [1–4]. With substantial differences between HICs and LMICs regarding health resources, environment, infrastructure, technology, and medical personnel, addressing prevention and treatment of cancer in LMIC settings may require a different evidence base [5–7]. Given the varying local resources and capacity, extrapolating from research conducted by and for HICs could lead to inappropriate conclusions and strategies [8–10]. That said, for complex non-communicable diseases like cancer, diagnosis and treatment can, similarly, be technically and medically complicated [3]. Making presumptions about the inability of LMICs to adopt best-practices identified elsewhere is equally problematic [11] since relative success in many LMICs with preventing and controlling other technically-intensive complex diseases like HIV was perhaps more successful (in some logistical aspects) than initially expected [12]. An evidence base developed within LMICs is necessary to inform optimal and effective care and successful strategies for cancer control, while avoiding erroneous assumptions and extrapolations from work done in high-income countries [13].

Though considerable regional variation exists, the cumulative probability of breast cancer for women aged 15–79 years in less developed countries in 2010 was 3.8% (95% CI: 3.4–4.1), closer to 50% higher than the rate from 1980 (2.4%; 95% CI: 2.1–2.9) [14]. The cumulative probability of cervical cancer for women aged 15–79 years in less developed countries in 2010 was 1.2% (95% CI: 0.9–1.6), slightly lower than the rate in 1980 (2.6%; 95%CI:1.7–3.3).[14] The cumulative probability of death from breast cancer for women aged 15–79 years in less developed countries in 2010 was 2.1% (95%CI: 1.7–2.3) a two-fold increase from 1980 levels (1.1%; 95% CI: 1.0–1.3) [14]. For cervical cancer the cumulative probability of death in 2010 was 0.5% (95%CI: 0.3–0.7) a third of what it was in 1980 (1.5%: 95% CI 1.0–1.9) [14]. Cancer patterns globally are anticipated to continue shifting [15], as infection-related cancers begin to decline and cancers relating to diet, lifestyle, and hormones increase, particularly in less developed countries [16].

To date, a wide range of systematic and non-systematic literature reviews have been conducted examining breast and cervical cancer control in LMICs. The purpose of this paper was to conduct a scoping study assessing the current status of published evidence for best practices across the care continuum for breast and cervical cancer in LMICs and to identify common themes and gaps that could be addressed with future research and systematic reviews. Specifically, the guiding research question was what reviews have indicated best practice for prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship for breast and cervical cancer in LMICs. Researchers often undertake such “scoping studies” to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity and identify gaps in the existing literature [17]. Given the wide range of study designs utilized in LMICs, a scoping study—essentially a “reviews of reviews”—is ideal to ascertain current evidence around breast and cervical cancer control in LMICs.

Methods

A scoping study of breast and cervical cancer control in LMICs was conducted following the six-stage framework of Arskey and O’Malley [18] and the additional recommendations of Levac et al. [17]. This type of methodological approach attempts to systematically locate literature and classify it, but does not aim to exclude studies based on methodological quality nor to produce quantitative syntheses. Instead, scoping reviews aim to describe and summarize research findings on a specific topic and to highlight research gaps. The six stages of the framework and our specific methods are outlined below.

1. Research question

Following the recommendations of Levac et al. [17], we linked our research question (“What reviews have indicated best practice for prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship for breast and cervical cancer in LMICs?”)with the purpose of the scoping study (“Identify key themes, recommendations, and research/ practice gaps for breast and cervical cancer control in LMICs”). Our primary interest was to examine the range of reviews on breast and cervical cancers in LMICs and identify priority areas for future systematic reviews and future research where the research base is lacking.

2. Identification of relevant studies

Searches in PubMed, Cochrane Review, and CINHAL were conducted with the following inclusion criteria: 1) published between 2005-February 2015, 2) focus on women with breast and cervical cancer, 3) focused on LMICs countries, 4) review article, and 5) published in English language. Subsequently, the search strategy for breast cancer reviews in PubMed included: ("Breast Neoplasms" (MeSH)) AND "Developing Countries" (MeSH); Filters: review; published in the last 10 years). For cervical cancer searches breast cancer was replaced by ("Uterine Cervical Neoplasms"(MeSH)). For details on MeSH subheadings please see S1 Text. In addition, “developing countries(MeSH)” was replaced by the keyword “low-income countries” and “low-income country” and unique reviews were included in the review. A few reviews [n = 3] that were not initially detected in our search because they focused on specific countries, or lacked a keyword match, but were identified by our research team as relevant to our objective were included.

3. Study selection

Two members of the abstraction team reviewed each manuscript for two study selection criteria: 1) a focus on cervical and breast cancer in LMICs, and 2) reflected a literature review rather than empirical research itself. A third member of the abstraction team resolved discrepancies regarding which studies to include.

4. Charting the data

The abstraction team consisted of eight of the authors. Two members of the abstraction team reviewed each manuscript. Items abstracted included: type of review (consensus statement—a comprehensive analysis by a panel of experts; systematic review—organized method of locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature; or non-systemic review—a narrative review of a body of literature but not systematically), cancer care continuum (based on the U.S. National Cancer Institutes definitions: prevention, detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship [19]), focus (general objective), research findings/recommendations, research/practice gaps, and limitations. A third member of the abstraction team resolved discrepancies.

5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

We include a descriptive numerical summary of the reviews and a qualitative thematic analysis by the synthesis team to summarize findings across the cancer care continuum. The synthesis team was divided into three groups focusing on: 1) cervical cancer; 2) breast cancer; and 3) general themes. Each group reviewed the abstraction tables for themes separately and then the entire team met and discussed the themes that emerged and how best to report the results. A second round of data abstraction occurred after our synthesis meeting to capture more information about the themes identified. We assessed whether studies were based on LMICs (predominantly, partially, little, none from LMIC settings), the geographical focus of the review (global, LMIC, or a specific country), whether methods (e.g. strategy, terms, sources, inclusion/exclusion criteria) were described clearly (yes, no). Finally to summarize and collate the topic areas of each review, the abstraction team determined if a review focused on technological/behavioral interventions and implementation science themes. Reviews were categorized by topic based on if they reviewed studies regarding the theme, made recommendations based on the theme, both, or neither. Reviews were labeled behavioral or technical intervention if the authors assessed that the reviewed studies included an intervention design that focused either on changing behaviors (e.g. education) or technical (e.g. technological innovation in screening). In determining a review’s consideration of implementation science, we judged the inclusion of four major themes relying on Peters et al, 2009 [20] and 2013 [21]: governance, organizational-improvement, workforce capacity, and person- or community-centeredness (Table 1).

Table 1. Implementation science themes.

| Implementation science theme | Key terms | Example from reviews |

|---|---|---|

| Governance | Policy, regulation, financing, public education, needs, constraints, barriers, and partnerships | “National policies are the platform for effective immunization programs” [71]. |

| Organizational improvement | Implementation, quality improvement, quality assurance, performance management, guidelines, and systems strengthening. | “Where one or two dedicated staff had been designated to manage the services (coordinating facility activities, managing the screening itself, notifying women of test results, and ensuring follow-up care), services functioned much more effectively” [115]. |

| Workforce capacity | Training, continuing education, and peer learning | “Health professional education should address surveillance for breast cancer recurrence and second primary cancers, including patient characteristics and other risk assessments” [93]. |

| Community- or person-centeredness | Community empowerment, participation, information and education, social marketing, community-managed services, public health approaches, and community mobilization | “A key feature of a self-collected HPV testing strategy (SC-HPV) is the move of the primary screening activities from the clinic to the community” [24]. |

Reporting in this analysis adheres to the PRISMA guidelines for reporting results of systematic reviews (S1 Table) [22]. PRISMA stands for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

6. Consultation

The manuscript was shared with the entire research team for feedback, insights, and editing.

Results

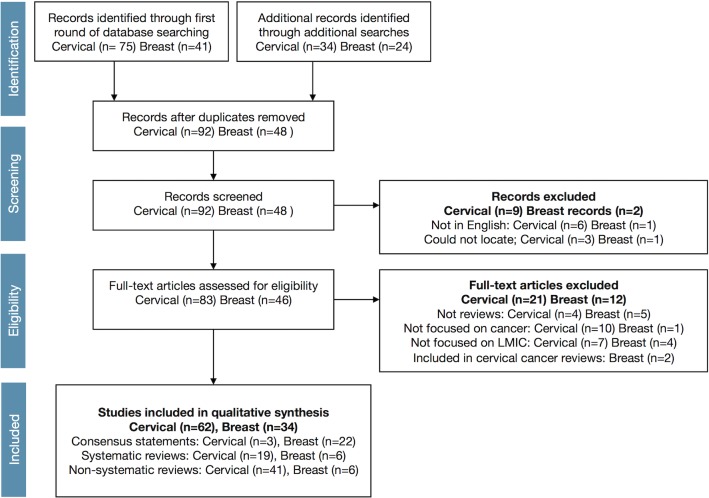

The search strategy implemented resulted in 62 reviews of cervical cancer and 34 reviews of breast cancer in LMIC settings that met our eligibility criteria (Fig 1). Cervical and breast cancer reviews differed substantially (Table 2). The cervical cancer literature reflected a substantially larger volume and distribution of both systematic [14, 23–40] and non-systematic reviews [12, 41–80], while the breast cancer literature predominantly consisted of consensus statements [81–102], with fewer systematic [103–108] or non-systematic [109–115] reviews. The cervical cancer literature also contained three consensus statements [116–118].

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram for review of manuscripts.

Table 2. Descriptive summary of breast and cervical cancer reviews in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

| Cervical cancer | Breast cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 63 | n = 36 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Type of reviews | ||

| Consensus statements | 3 (5) | 23 (64) |

| Systematic reviews | 18 (29) | 6 (17) |

| Non-systematic reviews | 43 (68) | 7 (19) |

| Cancer care continuum (categories not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Prevention | 41 (65) | 4 (11) |

| Detection | 32 (51) | 10 (28) |

| Diagnosis | 15 (24) | 10 (28) |

| Treatment | 16 (25) | 12 (33) |

| Survivorship | 3 (5) | 5 (14) |

| All | 1 (2) | 12 (33) |

| Data from LMIC | ||

| Predominantly (>80%) | 22 (35) | 6 (17) |

| Partially (30–<80%) | 29 (46) | 6 (17) |

| Little (1–<30%) | 12 (19) | 24(67) |

| Review focus on: | ||

| Global issues | 18 (29) | 1 (3) |

| LMIC | 37 (59) | 30 (83) |

| One region | 3 (5) | 2 (6) |

| One country | 4 (6) | 3 (8) |

| Methods clearly described | ||

| Yes | 14 (22) | 11 (31) |

| No | 49 (78) | 25 (69) |

Cervical cancer and breast cancer reviews also differed in their focus and content (Table 2). Cervical cancer reviews focused more on prevention and detection, while breast cancer reviews focused more on diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship, or more general aspects of all dimensions. Few of the breast cancer reviews referenced research and data from LMICs themselves; cervical cancer reviews were more likely to do so. Cervical cancer reviews were more globally focused, while breast cancer reviews focused more specifically on low-income regions. The wide majority of reviews in both areas (breast and cervical cancer) did not present transparent methods. Few studies reported even a subset of PRISMA elements [22].

Themes were identified if reviewed, recommended, or both, within a particular paper (Table 3). Most reviews included both (recommended and reviewed) regarding technical and behavioral interventions (Table 3). Frequently, reviews provided recommendations on a topic without first presenting an analysis of the literature on that topic. For instance, cervical cancer reviews (Table 4) tended to include recommendations around issues of governance and systems development. Similarly, both cervical and breast cancer reviews (Table 5) included recommendations around workforce capacity and person/community-centeredness. Breast cancer reviews (Table 3) were more likely to include recommendations around topics actually reviewed in all themes.

Table 3. Emerging thematic areas from breast and cervical cancer reviews in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

| Cervical cancer | Breast cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 63 | n = 36 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Technical/behavioral interventions a | ||

| Both reviewed and recommended | 42 (67) | 33 (92) |

| Reviewed | 7 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Recommended | 11 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Neither | 3 (5) | 3 (8) |

| Governance b | ||

| Both reviewed and recommended | 19 (30) | 16 (44) |

| Reviewed | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Recommended | 21 (33) | 3 (8) |

| Neither | 21 (33) | 17 (47) |

| Systems development c | ||

| Both reviewed and recommended | 15 (24) | 15 (42) |

| Reviewed | 4 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Recommended | 21 (33) | 5 (14) |

| Neither | 23 (37) | 16 (44) |

| Workforce capacity d | ||

| Both reviewed and recommended | 10 (16) | 14 (39) |

| Reviewed | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Recommended | 11 (17) | 6 (17) |

| Neither | 41 (65) | 16 (44) |

| Person/community centeredness e | ||

| Both reviewed and recommended | 11 (17) | 12 (33) |

| Reviewed | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Recommended | 8 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Neither | 43 (68) | 21 (58) |

Note: “Reviewed” indicates that the publication reviewed studies that pertained to this theme. “Recommended” indicates that the publication presented recommendations on the given subject.

a Include reviews that assess technical or behavioral interventions

b Includes reviews that discuss policy, regulation, financing, public education, needs, constraints, barriers, and partnerships.

c Includes reviews that discuss considerations of organizational improvement would have commented on topics such as implementation, quality improvement, quality assurance, performance management, guidelines, and systems strengthening.

d Includes reviews that discuss training, continuing education, and peer learning.

e includes reviews that discuss considerations of community empowerment, participation, information and education, social marketing, community-managed services, public health approaches, and community mobilization

Table 4. Reviews of cervical cancer in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

| Authors | Year | Care continuum. a | Focus | Data from LMICs | Trans-parent methods | Tech./ Behav. Inter-vention | Gover-nance | Health systems included | Work-force capacity | Person or comm. Centered-ness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONSENSUS STATEMENT | ||||||||||

| Bradley et al. | 2005 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Jacob et al. | 2005 | T | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Tangjitgamol et al. | 2009 | De, Di, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| SYSTEMATIC–QUALITATIVE | ||||||||||

| Bello et al. | 2011 | P | Region | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Chamot et al. | 2010 | T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cunningham et al. | 2014 | P | Region | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Elit et al. | 2011 | De, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Fesenfeld et al. | 2013 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Gravitt et al. | 2011 | P, De, Di | Global | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Katz et al. | 2010 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| McClung & Blumenthal | 2012 | T | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Rizvi et al. | 2006 | All | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Sankaranarayanan et al. | 2006 | De | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Sankaranarayanan et al. | 2012 | Di | Global | X | X | X | ||||

| Tsu et al. | 2005 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Williams-Brennan | 2013 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| SYSTEMATIC–QUANTITATIVE | ||||||||||

| Arbyn et al. | 2008 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Bradford & Goodman | 2013 | De | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Cuzick et al | 2008 | P, De, Di, T | Global | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Datta et al. | 2006 | Di, T, S | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Forouzanfar et al | 2011 | P | Global | X | X | X | ||||

| Sauvaget et al. | 2011 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| NON-SYSTEMATIC | ||||||||||

| Adefuye et al. | 2013 | P | Region | X | X | |||||

| Almonte et al. | 2011 | P, De | Global | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Anorlu et al. | 2007 | De, Di, T | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Batson et al. | 2006 | P | Global | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Belinson et al. | 2010 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Bharadwaj et al. | 2009 | P | Country | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Bradford et al. | 2013 | P, De | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Bradley et al. | 2006 | De, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Chirenje | 2005 | All | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Cronje | 2005 | P, De, Di, T | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cronje | 2011 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Denny | 2005 | P, De, Di | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Denny | 2012 | P, De, Di, T | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Denny (Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.) | 2012 | All | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Denny et al. | 2006 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Garcia-Carranca and Galvin | 2007 | P, De, Di | Global | X | X | X | ||||

| Hoppenot et al. | 2012 | P, De, Di, T | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Juneja et al. | 2007 | De | Country | X | X | X | ||||

| Kane et al. | 2012 | P | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Karimi Zarchi et al. | 2009 | P | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Lowy et al. | 2012 | P | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Luciani et al. | 2009 | P, De | Global | X | X | X | X | |||

| Natunen et al. | 2011 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Parkhurst et al. | 2013 | P, De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Patro et al. | 2007 | De | Country | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Reeler et al. | 2009 | P, De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Safaeian et al. | 2007 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Sahasrabuddhe et al. | 2011 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Saleem et al. | 2009 | P | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Sankaranarayanan et al. | 2005 | P, De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Sankaranarayanan et al. | 2006 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Sankaranarayanan et al. | 2009 | P | Global | X | X | |||||

| Saxena et al. | 2012 | De | Country | X | X | X | X | |||

| Sherris et al. | 2005 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Stanley | 2006 | P | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Stanley | 2007 | P | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Steben et al. | 2012 | P, De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Tomljenovic et al. | 2013 | P | Global | X | ||||||

| Tsu et al. | 2012 | P, De, Di, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Woo et al. | 2011 | P | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Wright et al. | 2012 | P, De, Di, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X |

a P = prevention, De = detection, Di = Diagnosis, T = Treatment, S = survivorship, All = all aspects

Table 5. Reviews of breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

| Authors | Year | Care continuum. a | Focus | Data from LMICs | Trans-parent methods | Tech./ Behav. Inter-vention | Gover-nance | Health systems included | Work-force capacity | Person or comm. Centered-ness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONSENSUS STATEMENT | ||||||||||

| Anderson et al. | 2006 | All | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Anderson et al. | 2015 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Anderson et al. | 2008 | All | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Anderson et al. (Breast J). | 2006 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Bese et al. | 2008 | T | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Cardoso et al. | 2013 | T, S | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cleary et al. | 2013 | T | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Corbex | 2012 | De | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| El Saghir et al | 2008 | T | LMIC | X | ||||||

| El Saghir et al. | 2011 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Enui et al. | 2006 | T | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Enui et al. | 2008 | T | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Ganz et al. | 2013 | S | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Harford et al. | 2008 | All | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Harford et al. | 2011 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Lodge & Corbex | 2011 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Masood et al. | 2008 | Di | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Shyyan et al. | 2006 | Di | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Shyyan et al.l | 2008 | All | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Smith et al. | 2006 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Wong et al | 2009 | T | Region | X | X | X | ||||

| Yip et al. | 2011 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Yip et al. | 2008 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| SYSTEMATIC | ||||||||||

| Asadzadeh et al | 2011 | P, De | Country | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Chavarri-Guerra | 2012 | All | Country | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| El Saghir et al | 2007 | Di, S | Region | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Lee | 2012 | All | Country | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Patani et al. | 2013 | Di, T | Global | X | X | X | ||||

| Zelle and Baltussen | 2013 | De, Di, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| NON-SYSTEMATIC | ||||||||||

| Al-Foheidi et al. | 2013 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Kantelhardt et al. | 2008 | D, T | LMIC | X | X | X | X | |||

| Keshtgar et al | 2011 | De, Di | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Panieri | 2012 | De | LMIC | X | X | X | ||||

| Romeiu | 2011 | P | LMIC | X | ||||||

| Shetty | 2011 | De, Di | LMIC | X | X | |||||

| Yip and Taib | 2012 | All | LMIC | X | X | X | X | X |

a P = prevention, De = detection, Di = Diagnosis, T = Treatment, S = survivorship, All = all aspects

Discussion

Development of the evidence base for best practice around breast and cervical cancer across the cancer prevention-survivorship continuum is of primary importance to inform cancer control strategies in LMICs. In this scoping study, roughly twice as many reviews were identified relating to cervical cancer compared with breast cancer in LMICs. While cervical cancer predominates in morbidity and mortality in some areas of the world (e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa), overall breast cancer is more prevalent in LMICs than cervical cancer [14]. While systematic reviews of the literature from LMICs around breast and cervical cancer is lacking overall, it is particularly absent on breast cancer where only six systematic reviews were identified [16].

Evidence-based best practice arises from quality systematic reviews [118]. Production of the evidence base for both breast and cervical cancer, however, faces considerable challenges. Presently, most review papers addressing breast cancer in LMIC settings reflect consensus statements, likely the result of a lack of research in LMICs from which to form systematic (or even non-systematic) reviews. The majority of reviews around breast cancer in LMICs are not based on research generated from LMICs themselves, meaning that best practices and strategies developed in high-income regions are forming the basis, through extrapolation and perhaps erroneous assumption, for low-income regions. While most of the cervical cancer literature targeting LMICs considered for this scoping study reflected reviews that did include at least partial data generated from LMIC settings, most were not systematic reviews from which to form summaries and recommendations. The majority of reviews included in each category (breast and cervical) did not provide a transparent description of methods; hence, findings and recommendations likely could be biased, or inappropriate, based on incomplete or non-representative reviews of selected studies.

Without quality systematic reviews of breast and cervical cancer studies based on research and data from LMICs themselves or why the evidence reviewed is thought to be applicable to those countries, the evidence base will likely remain incomplete, poorly replicable, and potentially recommending inaccurate and inappropriate strategies. Additionally, reviews (especially in the cervical cancer literature) commonly over-reached the data evaluated and included recommendations on issues not reviewed elsewhere in the published paper. This over-reaching was concentrated mostly on issues of governance and systems development, essential components of cancer control but frequently not the focus of empirical research [119].

Areas of focus for the reviews included in this scoping study indeed reflect research priorities to date around breast and cervical cancer. Largely because of rapid advances in HPV testing, vaccination, and visual inspection, cervical cancer reviews are more focused on prevention and detection than other phases of the continuum; in fact, only a few cervical cancer reviews focused on survivorship. In contrast, breast cancer reviews were much less likely to focus on prevention and more likely to focus upon treatment and survivorship, topics where more global research has been completed. While the HPV vaccine has shifted the focus to prevention in cervical cancer, mammography has yet to spark this type of shift in breast cancer [120]. In terms of themes, most of the reviews for breast and cervical cancer address technical and behavioral interventions, with far less focus on implementation science such as governance, systems development, workforce capacity, and person- and community-centeredness approaches.

This scoping study has limitations. First, with many similar assessments, the search strategy could be incomplete and miss papers in other sources or that were not coded with keywords used in this search. In a few instances, reviewers identified other papers not captured by the original search strategy. Further, search terms may not have identified all reviews relevant to LMIC but instead only those that deal with studies in LMIC. Second, our search identified seven non-English studies that were not included in this review. Third, this study was not an exhaustive search across gray literature and all databases for review materials on breast and cervical cancer. In addition, gray literature was not the focus of this review only peer-reviewed and indexed articles as we wanted to best understand the gaps in systematic reviews on breast cancer and cervical cancer. Finally, our synthesis of the reviews was limited by the fact that most reviews were non-systematic reviews in cervical cancer and with a notable proportion of consensus statements in breast cancer without strong foundations in systematic methods. This study’s strengths, however, include a systematic methodology, a large and interdisciplinary collaborating team, and the juxtaposition of breast and cervical cancer literature together creating opportunity for comparison.

In order to provide evidence-based options in LMIC around cervical and breast cancer that are scalable, research needs to arise from LMIC settings and needs to address implementation science. Further research in low-resource settings rather than extrapolating from high-resources settings is indicated by the scoping study, particularly around breast cancer control. In addition, few of the reviews considered in this scoping study research include research that draws from implementation science or makes recommendations based on implementation science. Future research is needed across all implementation science themes, but workforce capacity and community- or person-centeredness were especially under-considered in the reviews included in this scoping study.

Demonstration is needed that shows existing therapies, diagnostic tests, and interventions developed elsewhere can be as effective and practical in LMIC areas through implementation-oriented research and assessments [121]. Complex technologies and therapies with demonstrated effectiveness elsewhere typically require different implementation strategies in LMIC regions [122–124], but can produce real population benefit [11]. Breast and cervical cancer control in LMIC regions will likely remain suboptimal with excess morbidity and mortality continually observed without LMIC-based systematic reviews of implementation strategies that can generate evidence-based recommendations. As more and more technological advances are made in both breast and cervical cancer control in LMICs, the issues around implementation science and systems development become even more critical to ensure access and appropriate resource allocation.

Supporting Information

(XLSX)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Centers Program (Cooperative agreements: 1U48DP005026-01S1, 1U48DP005010-01S1, and 1U48DP005023-01S1). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This review falls under the scope of work for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded Global and Territorial Health Research Network through the Prevention Research Centers Program, with the goal to translate chronic disease prevention research into practice. In addition to several partnering institutions, the Global Network Steering Committee consists of two CDC representatives who participated in the study design and review of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author had final responsibility to submit the report for publication.

References

- 1. Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul FM, Shulman LN, Alleyne G, Armstrong L, et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. The Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Organization WH. World Cancer Report 2014 [ePUB]. WHO int; http://appswhoint/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams C, Alleyne G, Asaria P, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. The Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sylla BS, Wild CP. A million africans a year dying from cancer by 2030: what can cancer research and control offer to the continent? International Journal of Cancer. 2012;130(2):245–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lodge M. Ignorance Is Not Strength: The Need For A Global Evidence Base For Cancer Control In Developing Countries. Cancer Control. 2013:153. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wild CP. The role of cancer research in noncommunicable disease control. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(14):1051–8. 10.1093/jnci/djs262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vineis P, Wild CP. Global cancer patterns: causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2014;383(9916):549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miranda J, Kinra S, Casas J, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Non‐communicable diseases in low‐and middle‐income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008;13(10):1225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miranda JJ, Zaman MJ. Exporting" failure": why research from rich countries may not benefit the developing world. Revista de saúde pública. 2010;44(1):185–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebrahim S, Pearce N, Smeeth L, Casas JP, Jaffar S, Piot P. Tackling non-communicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: is the evidence from high-income countries all we need? PLoS medicine. 2013;10(1):e1001377 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farmer P. Infections and inequalities: The modern plagues: Univ of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reeler A, Qiao Y, Dare L, Li J, Zhang AL, Saba J. Women's cancers in developing countries: from research to an integrated health systems approach. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(3):519–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMichael C, Waters E, Volmink J. Evidence-based public health: what does it offer developing countries? Journal of Public Health. 2005;27(2):215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1461–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maule M, Merletti F. Cancer transition and priorities for cancer control. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(8):745–6. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70268-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(8):790–801. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute. Cancer control continuum (March 10, 2015). Available from: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/od/continuum.html.

- 20. Peters DH. Improving health service delivery in developing countries: from evidence to action: World Bank Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peters D, Tran N, Adam T. Implementation research in health: a practical guide Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chamot E, Kristensen S, Stringer JS, Mwanahamuntu MH. Are treatments for cervical precancerous lesions in less-developed countries safe enough to promote scaling-up of cervical screening programs? A systematic review. BMC women's health. 2010;10:11 10.1186/1472-6874-10-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gravitt PE, Belinson JL, Salmeron J, Shah KV. Looking ahead: a case for human papillomavirus testing of self-sampled vaginal specimens as a cervical cancer screening strategy. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2011;129(3):517–27. 10.1002/ijc.25974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katz IT, Ware NC, Gray G, Haberer JE, Mellins CA, Bangsberg DR. Scaling up human papillomavirus vaccination: a conceptual framework of vaccine adherence. Sexual health. 2010;7(3):279–86. 10.1071/SH09130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rizvi JH, Zuberi NF. Women's health in developing countries. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2006;20(6):907–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sankaranarayanan R, Nessa A, Esmy PO, Dangou JM. Visual inspection methods for cervical cancer prevention. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2012;26(2):221–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsu VD, Pollack AE. Preventing cervical cancer in low-resource settings: how far have we come and what does the future hold? International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2005;89 Suppl 2:S55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams-Brennan L, Gastaldo D, Cole DC, Paszat L. Social determinants of health associated with cervical cancer screening among women living in developing countries: a scoping review. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2012;286(6):1487–505. 10.1007/s00404-012-2575-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elit L, Jimenez W, McAlpine J, Ghatage P, Miller D, Plante M. SOGC-GOC-SCC Joint Policy Statement. No. 255, March 2011. Cervical cancer prevention in low-resource settings. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada: JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada: JOGC. 2011;33(3):272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McClung EC, Blumenthal PD. Efficacy, safety, acceptability and affordability of cryotherapy: a review of current literature. Minerva ginecologica. 2012;64(2):149–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fesenfeld M, Hutubessy R, Jit M. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2013;31(37):3786–804. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bello FA, Enabor OO, Adewole IF. Human papilloma virus vaccination for control of cervical cancer: a challenge for developing countries. African journal of reproductive health. 2011;15(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cunningham MS, Davison C, Aronson KJ. HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa: A systematic review. Preventive medicine. 2014;69:274–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cuzick J, Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Tsu V, Ronco G, Mayrand MH, et al. Overview of human papillomavirus-based and other novel options for cervical cancer screening in developed and developing countries. Vaccine. 2008;26 Suppl 10:K29–41. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Datta NR, Agrawal S. Does the evidence support the use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy as a standard in the management of locally advanced cancer of the cervix, especially in developing countries? Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)). 2006;18(4):306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sauvaget C, Fayette J-M, Muwonge R, Wesley R, Sankaranarayanan R. Accuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid for cervical cancer screening. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2011;113(1):14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Muwonge R, Keita N, Dolo A, Mbalawa CG, et al. Pooled analysis of the accuracy of five cervical cancer screening tests assessed in eleven studies in Africa and India. International journal of cancer. 2008;123(1):153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sankaranarayanan R. Overview of cervical cancer in the developing world. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2006;95 Suppl 1:S205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bradford L, Goodman A. Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention in Low-resource Settings. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2013. March; 56 (1): 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Batson A, Meheus F, Brooke S. Chapter 26: Innovative financing mechanisms to accelerate the introduction of HPV vaccines in developing countries. Vaccine. 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3/219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Reducing HPV-associated cancer globally. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa). 2012;5(1):18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sankaranarayanan R. HPV vaccination: the promise & problems. The Indian journal of medical research. 2009;130(3):322–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sherris J, Agurto I, Arrossi S, Dzuba I, Gaffikin L, Herdman C, et al. Advocating for cervical cancer prevention. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2005;89 Suppl 2:S46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anorlu RI, Ola ER, Abudu OO. Low cost methods for secondary prevention of cervical cancer in developing countries. The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal. 2007;14(3):242–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Belinson SE, Belinson JL. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening: practical aspects in developing countries. Molecular diagnosis & therapy. 2010;14(4):215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bharadwaj M, Hussain S, Nasare V, Das BC. HPV & HPV vaccination: issues in developing countries. The Indian journal of medical research. 2009;130(3):327–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bradford L, Goodman A. Cervical cancer screening and prevention in low-resource settings. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(1):76–87. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31828237ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chirenje ZM. HIV and cancer of the cervix. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2005;19(2):269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cronje HS. Cervical screening strategies in resourced and resource-constrained countries. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2011;25(5):575–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Juneja A, Sehgal A, Sharma S, Pandey A. Cervical cancer screening in India: strategies revisited. Indian journal of medical sciences. 2007;61(1):34–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kane MA, Serrano B, de Sanjose S, Wittet S. Implementation of human papillomavirus immunization in the developing world. Vaccine. 2012;30 Suppl 5:F192–200. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Karimi Zarchi M, Behtash N, Chiti Z, Kargar S. Cervical cancer and HPV vaccines in developing countries. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(6):969–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tomljenovic L, Shaw CA. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine policy and evidence-based medicine: are they at odds? Annals of medicine. 2013;45(2):182–93. 10.3109/07853890.2011.645353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saleem A, Tristram A, Fiander A, Hibbitts S. Prophylactic HPV vaccination: a major breakthrough in the fight against cervical cancer? Minerva medica. 2009;100(6):503–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adefuye PO, Broutet NJ, de Sanjose S, Denny LA. Trials and projects on cervical cancer and human papillomavirus prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccine. 2013;31 Suppl 5:F53–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cronje HS. Screening for cervical cancer in the developing world. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2005;19(4):517–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Denny L, Quinn M, Sankaranarayanan R. Chapter 8: Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries. Vaccine. 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3/71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Denny L. Cytological screening for cervical cancer prevention. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2012;26(2):189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Denny L. Cervical cancer: prevention and treatment. Discovery medicine. 2012;14(75):125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Denny L. The prevention of cervical cancer in developing countries. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2005;112(9):1204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Garcia Carranca A, Galvan SC. Vaccines against human papillomavirus: perspectives for controlling cervical cancer. Expert review of vaccines. 2007;6(4):497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hoppenot C, Stampler K, Dunton C. Cervical cancer screening in high- and low-resource countries: implications and new developments. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2012;67(10):658–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Natunen K, Lehtinen J, Namujju P, Sellors J, Lehtinen M. Aspects of prophylactic vaccination against cervical cancer and other human papillomavirus-related cancers in developing countries. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;2011:675858 10.1155/2011/675858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Parkhurst JO, Vulimiri M. Cervical cancer and the global health agenda: Insights from multiple policy-analysis frameworks. Glob Public Health. 2013;8(10):1093–108. 10.1080/17441692.2013.850524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Safaeian M, Solomon D, Castle PE. Cervical cancer prevention—cervical screening: science in evolution. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):739–60, ix. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sankaranarayanan R, Gaffikin L, Jacob M, Sellors J, Robles S. A critical assessment of screening methods for cervical neoplasia. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2005;89 Suppl 2:S4–s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Saxena U, Sauvaget C, Sankaranarayanan R. Evidence-based screening, early diagnosis and treatment strategy of cervical cancer for national policy in low- resource countries: example of India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(4):1699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stanley M. Prophylactic HPV vaccines: prospects for eliminating ano-genital cancer. British journal of cancer. 2007;96(9):1320–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stanley M. HPV vaccines. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2006;20(2):279–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Steben M, Jeronimo J, Wittet S, Lamontagne DS, Ogilvie G, Jensen C, et al. Upgrading public health programs for human papillomavirus prevention and control is possible in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2012;30 Suppl 5:F183–91. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tsu V, Murray M, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus vaccination in low-resource countries: lack of evidence to support vaccinating sexually active women. British journal of cancer. 2012;107(9):1445–50. 10.1038/bjc.2012.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Woo YL, Omar SZ. Human papillomavirus vaccination in the resourced and resource-constrained world. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2011;25(5):597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wright TC Jr, Kuhn L. Alternative approaches to cervical cancer screening for developing countries. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2012;26(2):197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Luciani S, Jauregui B, Kieny C, Andrus JK. Human papillomavirus vaccines: new tools for accelerating cervical cancer prevention in developing countries. Immunotherapy. 2009;1(5):795–807. 10.2217/imt.09.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Patro BK, Nongkynrih B. Review of screening and preventive strategies for cervical cancer in India. Indian journal of public health. 2007;51(4):216–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bradley J, Coffey P, Arrossi S, Agurto I, Bingham A, Dzuba I, et al. Women's perspectives on cervical screening and treatment in developing countries: experiences with new technologies and service delivery strategies. Women & health. 2006;43(3):103–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sahasrabuddhe VV, Parham GP, Mwanahamuntu MH, Vermund SH. Cervical cancer prevention in low- and middle-income countries: feasible, affordable, essential. Cancer prevention research [Philadelphia, Pa]. 2012;5(1):11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Almonte M, Sasieni P, Cuzick J. Incorporating human papillomavirus testing into cytological screening in the era of prophylactic vaccines. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2011;25(5):617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sankaranarayanan R, Ferlay J. Worldwide burden of gynaecological cancer: the size of the problem. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2006;20(2):207–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Anderson BO, Shyyan R, Eniu A, Smith RA, Yip CH, Bese NS, et al. Breast cancer in limited-resource countries: an overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative 2005 guidelines. The breast journal. 2006;12 Suppl 1:S3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Eniu A, Carlson RW, El Saghir NS, Bines J, Bese NS, Vorobiof D, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: treatment resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2269–81. 10.1002/cncr.23843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Smith RA, Caleffi M, Albert US, Chen TH, Duffy SW, Franceschi D, et al. Breast Cancer in Limited‐Resource Countries: Early Detection and Access to Care. The breast journal. 2006;12(s1):S16–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Anderson BO, Yip CH, Ramsey SD, Bengoa R, Braun S, Fitch M, et al. Breast Cancer in Limited‐Resource Countries: Health Care Systems and Public Policy. The breast journal. 2006;12(s1):S54–S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Shyyan R, Masood S, Badwe RA, Errico KM, Liberman L, Ozmen V, et al. Breast Cancer in Limited‐Resource Countries: Diagnosis and Pathology. The breast journal. 2006;12(s1):S27–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Anderson BO, Jakesz R. Breast cancer issues in developing countries: an overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative. World journal of surgery. 2008;32(12):2578–85. 10.1007/s00268-007-9454-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bese NS, Munshi A, Budrukkar A, Elzawawy A, Perez CA. Breast radiation therapy guideline implementation in low- and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2305–14. 10.1002/cncr.23838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cardoso F, Bese N, Distelhorst SR, Bevilacqua JL, Ginsburg O, Grunberg SM, et al. Supportive care during treatment for breast cancer: resource allocations in low- and middle-income countries. A Breast Health Global Initiative 2013 consensus statement. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2013;22(5):593–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Cleary J, Ddungu H, Distelhorst SR, Ripamonti C, Rodin GM, Bushnaq MA, et al. Supportive and palliative care for metastatic breast cancer: resource allocations in low- and middle-income countries. A Breast Health Global Initiative 2013 consensus statement. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2013;22(5):616–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Corbex M, Burton R, Sancho-Garnier H. Breast cancer early detection methods for low and middle income countries, a review of the evidence. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2012;21(4):428–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. El Saghir NS, Adebamowo CA, Anderson BO, Carlson RW, Bird PA, Corbex M, et al. Breast cancer management in low resource countries (LRCs): consensus statement from the Breast Health Global Initiative. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2011;20 Suppl 2:S3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. El Saghir NS, Eniu A, Carlson RW, Aziz Z, Vorobiof D, Hortobagyi GN. Locally advanced breast cancer: treatment guideline implementation with particular attention to low- and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2315–24. 10.1002/cncr.23836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ganz PA, Yip CH, Gralow JR, Distelhorst SR, Albain KS, Andersen BL, et al. Supportive care after curative treatment for breast cancer (survivorship care): resource allocations in low- and middle-income countries. A Breast Health Global Initiative 2013 consensus statement. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2013;22(5):606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Harford J, Azavedo E, Fischietto M. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: breast healthcare program resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2282–96. 10.1002/cncr.23841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lodge M, Corbex M. Establishing an evidence-base for breast cancer control in developing countries. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2011;20 Suppl 2:S65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Masood S, Vass L, Ibarra JA Jr, Ljung BM, Stalsberg H, Eniu A, et al. Breast pathology guideline implementation in low- and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2297–304. 10.1002/cncr.23833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Shyyan R, Sener SF, Anderson BO, Garrote LM, Hortobagyi GN, Ibarra JA Jr, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: diagnosis resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2257–68. 10.1002/cncr.23840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wong NS, Anderson BO, Khoo KS, Ang PT, Yip CH, Lu YS, et al. Management of HER2-positive breast cancer in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian Oncology Summit 2009. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10(11):1077–85. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70230-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Yip CH, Smith RA, Anderson BO, Miller AB, Thomas DB, Ang ES, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: early detection resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2244–56. 10.1002/cncr.23842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yip CH, Cazap E, Anderson BO, Bright KL, Caleffi M, Cardoso F, et al. Breast cancer management in middle-resource countries (MRCs): consensus statement from the Breast Health Global Initiative. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2011;20 Suppl 2:S12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. El Saghir NS, Khalil MK, Eid T, El Kinge AR, Charafeddine M, Geara F, et al. Trends in epidemiology and management of breast cancer in developing Arab countries: a literature and registry analysis. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2007;5(4):225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Anderson BO, Ilbawi AM; El Saghir NS. Breast Cancer in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs): A Shifting Tide in Global Health. Breast Journal, 2015. Jan-Feb; 21(1): 111–8. 10.1111/tbj.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Asadzadeh VF, Broeders MJ, Kiemeney LA, Verbeek AL. Opportunity for breast cancer screening in limited resource countries: a literature review and implications for Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(10):2467–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Patani N, Martin LA, Dowsett M. Biomarkers for the clinical management of breast cancer: international perspective. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2013;133(1):1–13. 10.1002/ijc.27997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zelle SG, Baltussen RM. Economic analyses of breast cancer control in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Systematic reviews. 2013;2:20 10.1186/2046-4053-2-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lee BL, Liedke PE, Barrios CH, Simon SD, Finkelstein DM, Goss PE. Breast cancer in Brazil: present status and future goals. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(3):e95–e102. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70323-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Chavarri-Guerra Y, Villarreal-Garza C, Liedke PE, Knaul F, Mohar A, Finkelstein DM, et al. Breast cancer in Mexico: a growing challenge to health and the health system. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(8):e335–43. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70246-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Keshtgar M, Zaknun JJ, Sabih D, Lago G, Cox CE, Leong SP, et al. Implementing sentinel lymph node biopsy programs in developing countries: challenges and opportunities. World journal of surgery. 2011;35(6):1159–68; discussion 5–8. 10.1007/s00268-011-0956-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Panieri E. Breast cancer screening in developing countries. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2012;26(2):283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Shetty MK. Screening and diagnosis of breast cancer in low-resource countries: what is state of the art? Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2011;32(4):300–5. 10.1053/j.sult.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Yip CH, Taib NA. Challenges in the management of breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Future oncology [London, England]. 2012;8(12):1575–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Al-Foheidi M, Al-Mansour MM, Ibrahim EM. Breast cancer screening: review of benefits and harms, and recommendations for developing and low-income countries. Medical oncology [Northwood, London, England]. 2013;30(2):471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Romieu I. Diet and breast cancer. Salud publica de Mexico. 2011;53(5):430–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Kantelhardt EJ, Hanson C, Albert U, Wacker J. Breast cancer in countries of limited resources. Breast Care, 2008. February; 3 (1): 10–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Bradley J, Barone M, Mahe C, Lewis R, Luciani S. Delivering cervical cancer prevention services in low-resource settings. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2005;89 Suppl 2:S21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Jacob M, Broekhuizen FF, Castro W, Sellors J. Experience using cryotherapy for treatment of cervical precancerous lesions in low-resource settings. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2005;89 Suppl 2:S13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Tangjitgamol S, Anderson BO, See HT, Lertbutsayanukul C, Sirisabya N, Manchana T, et al. Management of endometrial cancer in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian Oncology Summit 2009. The lancet oncology. 2009;10(11):1119–27. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70290-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Cochrane AL, Fellowship RC. Effectiveness and efficiency: random reflections on health services: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; London; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 119. Frenk J, Moon S. Governance challenges in global health. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(10):936–42. 10.1056/NEJMra1109339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Pinsky RW, Helvie MA. Role of Screening Mammography in Early Detection/Outcome of Breast Cancer Ductal Carcinoma In Situ and Microinvasive/Borderline Breast Cancer: Springer; 2015. p. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 121. Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, Hofman KJ. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. Jama. 2004;291(21):2616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kanavos P, Vandoros S, Garcia-Gonzalez P. Benefits of global partnerships to facilitate access to medicines in developing countries: a multi-country analysis of patients and patient outcomes in GIPAP. Global Health. 2009;5:19 10.1186/1744-8603-5-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kushner AL, Kamara TB, Groen RS, Fadlu-Deen BD, Doah KS, Kingham TP. Improving access to surgery in a developing country: experience from a surgical collaboration in Sierra Leone. Journal of surgical education. 2010;67(4):270–3. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Kibriya M, Ali L, Banik N, Khan AA. Home monitoring of blood glucose (HMBG) in Type-2 diabetes mellitus in a developing country. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 1999;46(3):253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.