Abstract

Gastric cancer, a highly heterogeneous disease, is the second leading cause of cancer death and the fourth most common cancer globally, with East Asia accounting for more than half of cases annually. Alongside TNM staging, gastric cancer clinic has two well-recognized classification systems, the Lauren classification that subdivides gastric adenocarcinoma into intestinal and diffuse types and the alternative World Health Organization system that divides gastric cancer into papillary, tubular, mucinous (colloid), and poorly cohesive carcinomas. Both classification systems enable a better understanding of the histogenesis and the biology of gastric cancer yet have a limited clinical utility in guiding patient therapy due to the molecular heterogeneity of gastric cancer. Unprecedented whole-genome-scale data have been catalyzing and advancing the molecular subtyping approach. Here we cataloged and compared those published gene expression profiling signatures in gastric cancer. We summarized recent integrated genomic characterization of gastric cancer based on additional data of somatic mutation, chromosomal instability, EBV virus infection, and DNA methylation. We identified the consensus patterns across these signatures and identified the underlying molecular pathways and biological functions. The identification of molecular subtyping of gastric adenocarcinoma and the development of integrated genomics approaches for clinical applications such as prediction of clinical intervening emerge as an essential phase toward personalized medicine in treating gastric cancer.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Gene expression profiling, Molecular subtyping, Molecular classification

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second leading cause of cancer death and the fourth most prevalent malignancy worldwide, accounting for 8% of cancer incidence and 10% of cancer deaths [1]. In the United States, about 21,000 cases of gastric cancer (61% are men and 39% are women) were diagnosed and about 10,000 patients died from this disease in 2012 [2]. Many factors such as ineffective screening, diagnosis, and treatment approaches contribute to the high incidence and mortality rates of GC [3,4].

Tumor staging has been established and validated as the best predictor of patient survival. Besides tumor node metastasis (TNM) staging, gastric cancer clinic has two well-recognized classification systems, the Lauren classification that subdivides gastric adenocarcinoma into intestine and diffuse types and the alternative World Health Organization system that divides gastric cancer into papillary, tubular, mucinous (colloid), and poorly cohesive carcinomas. Both classification systems enable a better understanding of histogenesis and biology of gastric cancer yet have a limited clinical utility in guiding patient therapy, especially when dealing with the molecular heterogeneity of gastric cancer [5,6]. The TNM classification is the most important tool for planning treatment in oncology and for assessing the patient's prognosis. However, even the latest edition of the TNM classification has limited power to capture the complex cascade of progression events that derived from the heterogeneous clinical behavior of GC [7].

In the past decade, much progress has been made in identifying more accurately molecular GC subtypes by gene expression profiling based on microarray technologies [8]. Such advances hold a great promise in improving prognosis and identifying more appropriate therapies [9]. High-throughput large-scale molecular profiling data provide rich information that is unobtainable from morphological or clinical examinations alone. Unprecedented whole-genome-scale data have been catalyzing and advancing the molecular subtyping approach.

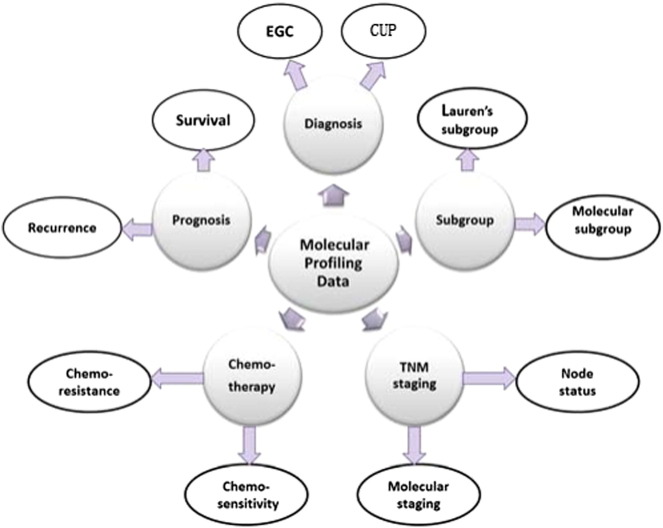

Here we cataloged and compared published gene expression profiling signatures in GC as well as more integrated genomic features of GC from gene expression, somatic mutation, chromosomal instability, Epstein–Bar Virus (EBV) virus infection, and DNA methylation. We highlighted the consensus patterns across these signatures, identified their associated molecular pathways, and underscored their prediction power of GC stratification and chemotherapy sensitivity. Fig. 1 outlines the contents of this review which focuses on applications of gene expression profiling in diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic intervention of GC.

Fig. 1.

Applications of molecular profiling in diagnosis and treatment of GC. The applications of gene expression profiling in GC include diagnosis, subgroup, TNM staging, treatment, and prognosis evaluation. EGC: early gastric cancer; CUP: cancer of unknown primary site.

2. Molecular diagnosis of GC

Gene expression signatures have successfully been identified to determine, differentiate, and categorize subtypes of GC as well as to solve some diagnostic dilemmas [8]. In early gastric cancer (EGC), tumor invasion is confined to the mucosa or submucosa regardless of the presence of lymph node metastasis or not [10]. Gene expression analysis identified a signature that differentiated EGC from normal tissue [10]. Boussioutas et al. analyzed 124 tumor and adjacent mucosa samples and explored the molecular features of gastric cancer, which could be discerned that readily defined premalignant and tumor subtypes, using DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling [11]. The identification of molecular signatures that are characteristic of subtypes of gastric cancer and associated premalignant changes should enable further analysis of the steps involved in the initiation and progression of gastric cancer. Vecchiet al. derived 1024 genes (52% up-regulated and 48% down-regulated) that were differentially expressed in 19 EGC samples when compared with 9 normal tissues [12]. The up-regulated genes are involved in cell cycle, RNA processing, ribosome biogenesis, and cytoskeleton organization, while the down-regulation genes are implicated in specific functions of the gastric mucosa (digestion, lipid metabolism, and G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway). Nam et al. [13] also identified a 973-gene signature to differentiate EGC from normal tissue using the microarray data from the matched tumor and adjacent non-cancerous tissues of 27 EGC patients [13]. They further demonstrated that the up-regulated genes in EGC tissues were correlated with cell migration and metastasis. Kim et al. demonstrated that 60 genes were gradually up or down-regulated in succession in normal mucosa, adenoma, and carcinoma samples by comparing the expression profiles of these tissues from eight patient-matched sets. Thus, molecular classification seems very promising for molecular diagnosis of EGC [14].

Both chronic gastritis (ChG) and intestinal metaplasia (IM) are involved in intermediate stage of GC, the former characterized by a mitochondria-related gene expression signature while the latter characterized by markers of proliferation [11]. Since ChG has mitochondria gene expression signature, it might be interesting to test whether such a signature is related to the metabolic subtype signature of GC [15]. Indeed, the differential expressed gene set between ChG and IM is largely overlapped with the GC metabolic signature (P = 0.00085, hypergeometric test).

Cancer of unknown primary site (CUP) is a well-recognized clinical disorder, accounting for 3–5% of all malignant epithelial tumors [12]. CUP can be identified based on conserved tissue-specific gene expression [16]. It has been shown that gene expression profiling can identify tissue of origin with an accuracy rate between 33% and 93% [17]. Anthony et al. applied a 92-gene CUP assay to tumor samples from patients with CUP. Fifteen of 20 cases (75%) were correctly predicted, i.e., those predicted CUPs were the actual latent primary sites that were identified after the initial diagnosis of CUP. This assay has been successfully applied to many other cancers such as breast, colorectal, and melanoma [18].

These gene signature-based methods can also be used to identify specific treatment for GC patients, i.e., targeted therapies. In a large prospective trial (n = 289), a gene expression signature was developed to predict the tissue of origin in most patients with CUP. The median survival time was 12.5 months for patients who received assay-directed site-specific therapy compared with the use of empiric CUP regimens. Patients whose CUP sites were predicted to have more responsive tumor types survived longer than those predicted to have less responsive tumor types [19]. These findings suggest that tumor molecular profiling can improve the treatment of patients with CUP and should be included in the standard evaluation [19].

While some great progresses have been made on molecular diagnosis based on gene expression profiling and many hospitals have built up facilities for molecular diagnosis, these technologies are still expensive and immature. Thus, reliable and cost-effective molecular diagnosis tools based on gene expression signatures have a broad development potential.

3. Molecular subtyping of GC

Histologically, GC shows great heterogeneity at both architectural and cytological levels and often has several co-existing tissue types such as well-developed tubular architecture and signet ring cell. The primary histopathologic classification used for GC was first described in 1965 by Lauren [20]. This classification simply divides gastric adenocarcinoma morphologically into two types: the diffuse and the intestinal types. The relative frequencies for intestinal, diffuse, and indeterminate types are approximately 54%, 32%, and 15%, respectively [21]. The intestinal type often has more well-developed tubular architecture while the diffuse type often includes poorly cohesive cells or signet ring cells [22]. Moreover, the diffuse type gastric cancer tends to carry germline mutations in genes involved in the cell adhesion protein E-cadherin; in contrast, the intestinal type is associated with atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and Helicobacter pylori infection [6]. However, such classification systems do not correspond well with the degree of malignance and survivability [23]. A recent study showed that alterations of tumor-related genes did not match the histopathologic grades in gastric adenocarcinomas [5]. Furthermore, the levels of pathological differentiation are barely consistent with the prognosis ones [5,24]. The lack of a well-established grading system for gastric cancer remains as a major obstacle hindering a better clinical practice in GC.

To have better GC stratification for clinical utility, extensive efforts have been made to classify gastric tumors based on gene expression profiling. Manish et al. [25] analyzed gene expression profiling of gastric adenocarcinoma samples from 36 individual primary tumors and developed a 785-gene signature to classify gastric cancer [25]. Based on epidemiologic, histopathologic, anatomic, and molecular evidence, they classified gastric cancer into 3 subtypes—proximal non-diffuse, diffuse, and distal non-diffuse gastric cancer. An independent study shows that more than 85% of the samples were classified correctly by the 785-gene signature. The diagnostic potential of this molecular classification was further improved by using histopathologic, anatomic, and epidemiologic information.

Moreover, gene expression profiling can be utilized for the development of response to treatments. Based on the gene expression profiling data from 37 GC cell lines, Tan et al. derived a signature of 171 genes to predict two major intrinsic genomic subtypes, G-INT, and G-DIF [26]. The G-INT cell lines were significantly more sensitive to 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin but more resistant to cisplatin than the G-DIF cell lines. In a subsequent study, Zheng et al. identified gene expression patterns to validate three subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma (proliferative, metabolic, and mesenchymal) [15]. Further, other levels of cancer genome features, such as genomic instability, TP53 mutations, and DNA hypomethylation, have been found in the tumors of the proliferative subtype. Cancer cells of the metabolic subtype are more sensitive to 5-fluorouracil than the other subtypes. Meanwhile, tumors of the mesenchymal subtype contain cells with characteristics of cancer stem cells and are particularly sensitive to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT-mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors (PI3K-AKT-mTOR). It is very likely that this approach holds a promise toward personalized treatment.

4. Molecular prediction of TNM staging

The lymph node status (N classification) is a strong predictor of the outcome, and lymph node metastases usually lead to poor prognosis. However, how to predict lymph node metastasis from primary tumor is almost impossible using only pathological data. Gene expression profiling data have been utilized for this purpose.

Ken et al. developed a 92-gene signature to stratify patients with lymph node metastasis and they achieved an accuracy of 92% [27]. These genetic signatures for predicting the lymph node status can help surgeons select patients who may benefit from extended lymph node dissection. Clinica et al. screened primary gastric cancer gene expression profiles to decide whether extended lymph node dissection is necessary [28]. In this study, gene expression was first measured in frozen tumor samples obtained from 32 patients with primary gastric adenocarcinomas and then a 136 gene signature was identified to predict lymph node status. The exceptional performance (96.8% prediction accuracy) suggests that this approach can be used to tailor the extent of lymph node dissection on an individual patient basis. Cui et al. analyzed 54 pairs of matched cancer and adjacent reference tissues and identified gene expression signatures for predicting cancer grades and stages [27]. Specifically, a 10-gene signature was identified to predict early stage (stage I + II) with an accuracy of 90% and a 9-gene signature was defined to predict advanced stage cancer (stage III + IV) with an accuracy of 84%.

Moreover, gene expression-based prediction on survival can have a better performance than TNM staging. Zhang et al. reported a similar result based on a microarray study of 72 GC samples [29]. These samples were divided into two sets, a training set with 39 samples and a validation set with 33 samples. A panel of ten genes was identified in the training set as a prognostic marker that was correlated to overall survival and further verified in the validation set. Compared with the traditional TNM staging system, this ten-gene prognostic marker showed consistent prognosis results and thus was complementary to the current staging system.

5. Molecular prediction of response to chemotherapy

Gene expression can also be used to predict whether a GC patient responds to certain therapies. Such approaches would help provide additional predictive information for personalized treatment. Pathologic complete response to chemotherapy indicates that some tumors are extremely sensitive to chemotherapy [30]. However, it remains extremely challenging to predict chemotherapy sensitivity based on histopathological data. Several microarray assays have been developed for this purpose (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gene expression profiling associated with sensitivity or resistance to anticancer drugs in GC.

| Signature | Samples | Drugs | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | Three sensitive and one resistant GC cell line | Cisplatin | Patterns of gene expression alteration after exposure to cisplatin/5-flu | Wesolowski and Ramaswamy[62] |

| 250 genes | Ten chemoresistant and 4 parent GC cell lines | Cisplatin | Offered gene information with acquired resistance | Kang et al. [65] |

| 13 genes | Eight GC cell lines | 5-FU | Provided biomarkers for 5-FU sensitivity/resistance | Park et al. [37] |

| 23 genes | 35 GC cases | 5-FU | Gave information regarding chemoresistance factors | Suganuma et al. [38] |

| 69 genes/5 flu and 45 genes/cisplatin | Three GC cell lines | 5-FU | Predicted responses to 5-flu | Ahn et al. [66] |

| 39 genes | NA | 5-FU | 39-gene signature with 5-FU resistance | Szoke et al. [67] |

| 119 genes | Seven GC cases | 5-FU/cisplatin | Distinguished chemosensitive state from the refractory state | Kim et al. [39] |

| four genes | Three cell lines and 37 GC | Paclitaxel | Provided new markers for resistance to paclitaxel | Murakami et al. [68] |

| NA | 30 cancer cell lines | 5-FU | constructed profiles of resistance against each chemotherapy agent | Gyorffy et al. [69] |

| NA | 45 cancer lines including 12 GC cell lines | 53 drugs | Established a sensitivity database for JFCR-4andatabase of the EGF | Nakatsu et al. [34] |

| 12 genes | 19 cell lines and 30 GC | 8 drugs | Developed prediction models of the 8 anticancer drugs | Tanaka et al. [33] |

| 85 genes | 13 GC cell lines | 16 drugs | Acted as markers for chemosensitivity in chemo-naive GC patients | Jung et al. [35] |

| seven genes | 20 GC cases and 19 GC validation | Doxorubicin | Predicted the response of GC to doxorubicin | Hao et al. [70] |

| MRP4 | One GC cell line(SGC7901) | Cisplatin | MRP4 is a DDP resistance candidate gene | Yan-Hong et al. [71] |

| NA | Three GC cell lines | Parthenolide | Enhanced chemosensitivity to paclitaxel in the treatment | Itsuro et al. [72] |

| NA | Three GC cell lines | Vorinostat | Vorinostat improved the outcomes of GC patients | Sofie et al. [73] |

| NA | Three GC cell lines | Metformin | Metformin inhibited GC cell and proliferation | Kiyohito et al. [74] |

At the early genome expression profiling stage, it has been shown that chemotherapy-sensitive tumors have significantly different gene expression than that from chemotherapy-resistant cases [31,32]. Tanaka et al. analyzed a microarray data from 19 cancer cell lines, including 2 GC cell lines, and developed a 12-gene signature to predict the response to 8 drugs (5-FU, CDDP, MMC,DOX, CPT-11, SN-38, TXL, and TXT) [33]. The signatures have the power to predict accurately not only the in vitro efficacy of the drugs but also GC patients' response including survival, time to treatment failure, and tumor growth to 5-FU. Nakatsu et al. established a panel of 45 human cancer cell lines (JFCR-45), including 12 stomach cancer cell lines [34]. They assessed the chemosensitivity of JFCR-45 to 53 anticancer drugs by growth inhibition experiments and built up a sensitivity database for JFCR-45 to anticancer drugs. Using these databases, they have identified gene signatures that can predict chemosensitivity of gastric cancer. Jung et al. developed G-matrix (gene expression database) and C-matrix (chemosensitivity database) from 13 gastric cancer cell lines treated with 16 anticancer agents using 22 K human oligo chips and identified an 85-gene signature be associated with chemosensitivity of gastric cancer with respect to the major anticancer drugs [35]. Recently, Ivanova et al. generated a comprehensive cohort including mRNA expression, DNA methylation, and cisplatin response data from 20 gastric cancer cell lines [36]. A panel of 291 genes was found to be differently expressed between the top four cell lines most sensitive to cisplatin and those most resistant lines. Notably, BMP4 was overexpressed in the cisplatin-resistant cell lines. Furthermore, BMP4 expression was significantly up-regulated (P = 4.53 × 10− 5; 2.25-fold enrichment) in 197 gastric cancer samples when compared with non-malignant gastric tissues. In primary tumors, BMP4 promoter methylation levels were inversely correlated with BMP4 expression, and GC patients with high BMP4 expression in tumor exhibited significantly worse prognosis. These results suggested that BMP4 epigenetic and expression status may represent promising biomarkers for GC cisplatin sensitivity.

The major cause of treatment failure for GC is the development of acquired resistance to chemotherapy. Gene expression signatures can be used to identify subgroups that will acquire resistance to chemotherapy. Such a strategy would provide additional predictive information for individualized treatment. Park et al. analyzed genes expression profiling of 5-FU sensitive and/or resistant GC cell lines [37]. A 13-gene signature was identified to predict response to 5-FU. Suganuma et al. identified a 23-gene signature for DDP resistance (cisplatin-resistance) by comparing the gene expression in 22 pairs of DDP-resistant tumor samples and surrounding normal tissues [38]. Similarly, Kim et al. compared the expression profiles from gastric cancer biopsy specimens obtained at a chemosensitive state with those obtained at a refractory state and identified 119 genes associated with acquired resistance to 5-FU/Cisplatin [39]. In another study, Kim et al. compared the gene expression profiling of 22 pre-CF (cisplatin and fluorouracil)-treated samples with that of the matched post-CF-treated samples and identified 72 differentially expressed genes as a signature for acquired resistance [40]. The 72-gene signature was an independent predictor for the time to progression and survival. In a similar study, they analyzed 90 gastric cancer patient samples and 34 healthy volunteers' samples using microRNA gene profiling. In total, 82 samples were used as a training set to discover candidate markers correlated to chemotherapy response, and 8 samples were used for validation. Fifty-eight microRNAs were found to be capable of discriminating patients who are likely or unlikely to respond favorably to CF therapy, suggesting that such a microRNA predictor can provide a useful guidance for personalized chemotherapy [41]. Taken together, genomic signatures derived from gene expression proofing have the capacity to connect clinical intervention especially in predicting sensitivity and resistance to specific chemotherapy regimens.

6. Molecular prognosis of GC

Another important function of GC Gene expression profiling is to predict which gastric cancer patients have good or poor clinical outcomes (Table 2). Many studies have shown that gene expression signatures can classify tumors into intrinsic subtypes and predict the survival of GC patients [26]. Several genomic studies also show that gene expression profiling can predict patients with a high risk for recurrence and thus can potentially improve clinical practice [42–44]. Now it is evident that gene expression techniques may significantly improve our ability to predict the risk of recurrence and to tailor the treatment for each individual gastric cancer patient.

Table 2.

Gene expression profiling for GC prognosis.

| Signature | Data set | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three oncogenic pathways | 25 GC cell lines of discover set and 300 cases of validation set | 3 oncogenic pathway combinations predicted clinical prognosis | Ooi et al. [75] |

| Two genomic subtypes (G-INT and G-DIF) | 37 GC cell lines of discover set and 521 cases of validation set | Associated with patient survival and response to chemotherapy | Tan et al. [26] |

| 98 genes | 40 cases of discover set and 19 cases of validation set | Predicted the overall survival | Yamada et al. [45] |

| Eight genes | Seven cases and four cases control | Had a predictive role in survival of metastatic patients | Lo Nigro et al. [46] |

| 82 genes signature | 30 pairs of gastric mucosa and cancer | Reflected the genetic information for hazard rate of recurrence | Kim and Rha [50] |

| Five genes | 33 cases of discover set and 125 cases of validation set | Independent prognostic factors for overall survival | Wang et al. [47] |

| Four genes | 48 cases | Predicted surgery-related survival | Xu et al. [76] |

| Six genes | 65 cases of discover set and 96 cases of validation set | Predicted the likelihood of relapse after curative resection | Cho et al. [49] |

| Two genes | Seven cases recurrence and four cases without recurrence | Acted as new prognostic biomarkers in predicting recurrence risk | Yan et al. [77] |

| hsa-miR-335 | 74 cases of discover set and 64 cases of validation set | Had the potential to recognize the recurrence risk | Yan et al. [78] |

| Three miRs | 45 cases | Predicted of recurrence of GC | Brenner et al. [79] |

| Two miRs | 65 cases of discover set and 57 cases of validation set | As a predictor of disease progression | Zhang et al. [80] |

| Five microRNA | 164 cases and 127 normal control | Expression levels of miRNAs indicated tumor progression stages | Kim and Chung [81] |

| CD26 | 32 cases of GIST | Played an important role in the progression of GISTs and serve as a therapeutic target | Yamaguchi et al. [82] |

| CCL18 | 90 cases of discover set and 59 cases of validation set | As an independent prognostic indicator | Leung et al. [83] |

| Three genes | 18 cases of discover set and 40 cases of validation set | Predicted surgery-related outcome | Chen et al. [84] |

| 22 genes | 56 cases of discover set and 85 cases of validation set | Be useful in prospective prediction of peritoneal relapse | Takeno et al. [48] |

| CD9 | senveGISTs of discover set and 117 GISTs of validation set | As potent prognostic markers in GIST | Setoguchi et al. [85] |

| 29 genes | 60 cases of discover set and 20 cases of validation set | Improved the prediction of recurrence in patients | Chen et al. [84] |

Gene expression data in tandem with clinical information have made it possible to construct the predictive models for the outcome of gastric cancer. Yamada et al. analyzed 40 endoscopic biopsy GC samples to identify a 98-gene signature that are significantly correlated with the overall survival [45]. In particular, PDCD6 was identified as a prognostic biomarker of GC through a multivariate analysis. Lo Nigro et al. compared gene expression profiling of 3 long-term survival cases with metastatic gastric cancer with that of 4 normal cases [46]. An 8-gene signature was identified to distinguish long survivors from the control cases. Wang et al. collected 158 gastric cancer patients, among which 33 cases were used as a training set and 125 cases for RT-PCR as a testing set [47]. A 5-gene signature was established for clinical and prognostic.

Recurrence and metastasis are the main causes for the death of GC patients. Genomic signatures have successfully been used to predict the relapse of GC. Peritoneal relapse is the most common pattern of tumor progression in advanced gastric cancer. Clinicopathological findings are often inadequate for predicting peritoneal relapse. Takeno et al. compared gene expression profiles of 38 relapse-free GC patients with those from 18 peritoneal relapse ones and developed a 22-gene signature to predict peritoneal relapse with an accuracy of 68% [48]. Cho also analyzed 65 gastric adenocarcinoma tissues and developed a risk score based on 6 genes to predict relapse of GC. This risk score was successfully tested in an independent cohort [49].

To establish prognostic index (PI) for each patient that reflects the genetic information, Kim et al. analyzed 30 pairs of gastric tumors and normal gastric tissues to develop genetic alteration score (GAS) for estimating patient's survival time by the cDNA microarray-based CGH [50]. GAS was based on 82 genes, and the prediction accuracy for recurrence was 83.33%. GAS was able to capture important genetic information for hazard rate of recurrence and distinguish a patient's recurrence status, survival status, and cancer stage status.

The development of predictive molecular models for GC treatment is still at an early stage, and those models need some substantial improvement for the use in clinical trials. High-quality studies should be conducted to develop accurate, reliable, and reproducible models for clinical practice. Only then will it be possible to use predictive models routinely to tailor GC treatment.

7. Comparison of predictive gene signatures in GC

Most genomic signatures were derived from data sets with a relative small sample size, raising the issue of reproducibility, especially when considering the heterogeneity nature of cancer. To examine whether those signatures are sample dependent or study specific, we systematically compared 21 gene signatures predictive of GC stages, chemotherapy response, and metastasis from 9 studies. These gene signatures had at least 70 genes and were derived from a relative larger sample population. Such selection criteria enable meaningful enrichment test.

As shown in Table 3, nine of the 21 signatures were from a recent study of GC subtypes with different responses to PI3-kinase inhibitors and 5-fluorouracil [15]. The signatures identified by Lei et al. [15] are the most comprehensive and significantly overlap with at least one signature in 7 of the other 8 studies. In this study, a cohort of 248 cases from Singapore (SG) were employed as discovering data set, with another cohort of 201 cases from Singapore and 70 cases from Australia (AU) for validation. Intriguingly, based on clinical traits, including Lauren's classification, stage of disease, a more detailed system can be obtained, involving DIF (diffused signature), INT (intestine signature), MET-sg (metabolic signature–Singapore), MET-au (metabolic signature–Australia), MES-sg (mesenchymal signature–Singapore), MES-au (mesenchymal signature–Australia), PRO-sg (proliferative signature–Singapore), and PRO-au (proliferative signature–Australia).

Table 3.

Descriptions of signatures used for a systematic comparison in Table 4.

| Signature | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CGH_Prog [50] | 70 | Prognosis signature of array CGH probes |

| DIF [15] | 78 | Expression signature of diffused type |

| G_DIF [26] | 79 | Diffusion type signature |

| MES [15] | 89 | Mesenchymal signature |

| G_INT [24] | 91 | Gastric intestine signature |

| INT [15] | 91 | Intestine signature |

| FU [35,38,39,52] | 131 | 5 Fu response signature |

| CDDP [35,38,39,52] | 224 | Cisplatin response signature |

| GA_NOR [50] | 264 | Gastric adenoma signature |

| AGC_NOR [11] | 309 | Advanced gastric cancer signature |

| MET_au [15] | 315 | Metabolic signature–Australia |

| GC_NOR [50] | 364 | Gastric carcinoma signature |

| CDDPFU [35,38,39,52] | 444 | 5 Fu and cisplatin response signature |

| AGC_Mut [83,84] | 446 | Advanced gastric cancer mutation signature |

| MET_sg [15] | 736 | Metabolic signature–Singapore |

| EGC_NOR [11] | 815 | Early gastric cancer |

| PRO_au [15] | 854 | Proliferative signature–Australia |

| EGC_Mut [85] | 857 | Early gastric cancer mutation signature |

| MES_au [15] | 1398 | Mesenchymal signature–Australia |

| PRO_sg [15] | 2244 | Proliferative signature–Singapore |

| MES_sg [15] | 2920 | Mesenchymal signature–Singapore |

Abbreviations and source literatures are listed in the first column of the table.

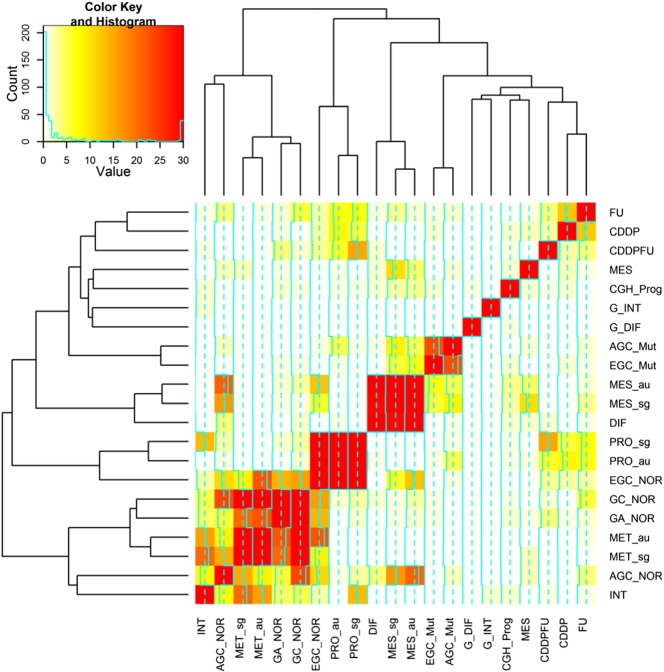

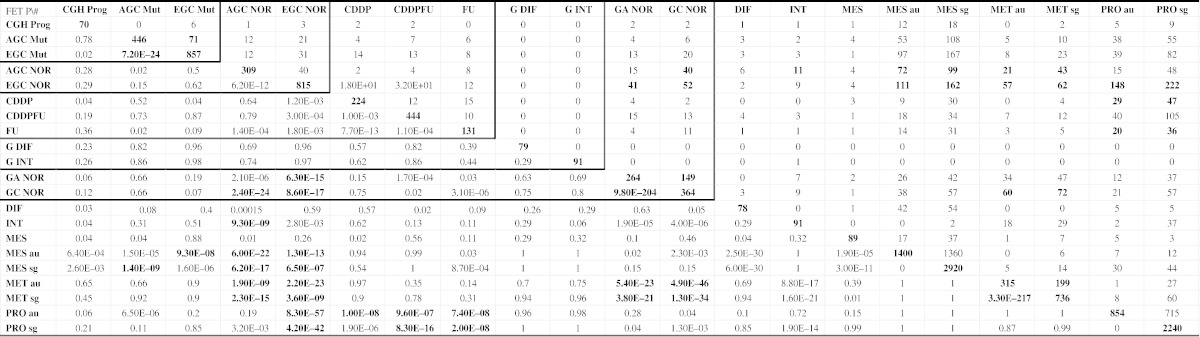

Table 4 and Fig. 2 show the overlaps between these signatures. To assess the statistical significance of an overlap between two differentially expressed gene signatures, we used the standard Fisher's exact test (FET) [51]. The INT signature significantly overlaps with MET-au and MET-sg, with FET P < 1.6E − 21 and P < 8.8E − 17, respectively. In contrast, the DIF signature overlaps more significantly with MES-sg and MES-au with FET P < 6.0E − 30 and P < 2.5E − 30, respectively, consistent to canonical Lauren's classification. The signature EGC_NOR (early gastric cancer signature) [12] highly overlaps with the proliferative signatures PRO_sg and PRO_au [15] with FET P < 4.2E − 42 and 8.3E − 57, respectively. Meanwhile, the signature AGC_NOR (advanced gastric cancer signature) is enriched in the MET signatures from the Singapore and Australia data sets [15] with FET P < 6.2E − 17 and 6.0E − 22, respectively, indicating the validity of this molecular subtype method. Moreover, the signature PRO_au [15] moderately overlaps with those chemotherapy response signatures, CDDP, CDDPFU, and FU [35,38,39,52] with FET P < 1.0E −8, 9.6E −7, and 7.4E −8, respectively, albeit with unknown mechanism. Interestingly, the signature EGC_NOR [12] significantly overlaps with GA_NOR [53] with FET P < 6.3E −15, and they share some important genes such as RBP2, FHL1, and NME1. RBP2 was found to be overexpressed in GC and plays some key roles in the process of gastric carcinogenesis [54,55]. FHL1, a tumor suppressor gene, is involved in migration, invasion, and growth in GC due to a loss-of-function mutation [56,57]. In summary, these signatures can improve our understanding the processes from benign tumor to malignant tumor of stomach.

Table 4.

Overlap between the gene signatures specified in Table 3. The diagonal of the matrix below represent the number of genes in each signature. The elements in the upper-right panel represent the number of genes shared by two signatures while those in the lower-left panel represent the corresponding p values computed based on the hypergeometric test.

Fig. 2.

Clustering analysis of gene sets based on the significance level of overlap between signatures. Details about the signatures can be found in Table 3. The similarity between two genes signatures was determined by lg(p value), where p value was based on the hypergeometric test.

8. Integrated genomic subtyping of GC

The large-scale molecular profiling data in GC at The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provide an excellent opportunity to develop advanced molecular classifiers and predictors for GC diagnosis and treatments. Based on the TCGA data in GC, four major molecular subtypes of GC were defined, and they include EBV-infected tumors, MSI tumors, genomically stable tumors, and chromosomally unstable tumors. The molecular classification not only serves as a valuable adjunct to histopathology but also shows distinct salient genomic features providing a guide to targeted agents [58].

Recently, Cristescu et al. analyzed gene expression data of 300 primary gastric tumors to establish four molecular subtypes linked to distinct patterns of molecular alterations, disease progression, and prognosis, which included MSS/EMT subtype, MSI subtype, MSS/TP53+ subtype, and MSS/TP53− subtype [59]. The MSS/EMT subtype includes diffuse-subtype tumors with the worst prognosis, the tendency to occur at an earlier age and the highest recurrence frequency (63%) of the four subtypes. MSI subtype contains hyper-mutated intestinal-subtype tumors occurring in the antrum, the best overall prognosis, and the lowest frequency of recurrence (22%) among the four subtypes. Patients of MSS/TP53 + and MSS/TP53 − subtypes have intermediate prognosis and recurrence rates, while the TP53-active group shows better prognosis. They also validated these subtypes in independent cohorts and showed that the four molecular subtypes were associated with not only recurrence pattern and prognosis but also distinct patterns of genomic alterations. These subtypes can provide a molecular subtyping framework for preclinical, clinical, and translational studies of GC.

Whole genomic sequencing has the capacity to define subtyping of GC at the DNA level. We summarized the recent advances in this direction in Table 5. These mutation signatures are anticipated to open a new avenue for targeted GC therapy.

Table 5.

Integrative gastric subtyping studies including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the Asia Cancer Research Group (ACRG), and diffusion gastric adenocarcinoma (DGC).

| System | Molecular subtypes | Sample size | Percentage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | 295 | |||

| EBV positive | 8.81 | TCGA [58] | ||

| MSI high | 21.69 | |||

| GS | 19.66 | |||

| CIN | 49.83 | |||

| ACRG | 300 | Cristescu et al. [59] | ||

| MSS/TP53 + | 35.70 | |||

| MSS/TP53 − | 26.30 | |||

| MSS/EMT | 15.30 | |||

| MSI | 22.70 | |||

| genomic alteration | Deng et al. [86] | |||

| FGFR2 | 9.00 | |||

| KRAS | 9.00 | |||

| EGFR | 8.00 | |||

| ERBB2 | 7.00 | |||

| MET | 37.00 | |||

| DGC-RHOA-Japan | 98 | Wang [87] | ||

| RHOA + | 14.70 | |||

| RHOA − | 85.30 | |||

| DGC-RHOA-HKU | 87 | |||

| RHOA + | 25.3 | Kakiuchi [88] | ||

| RHOA − | 74.7 | |||

| Mutation signature | 49 | Wong et al. [87] | ||

| TpT | 36.73 | |||

| CpG | NA | |||

| TpCp[A/T] | NA |

9. Biological functions underlying gene signatures in GC

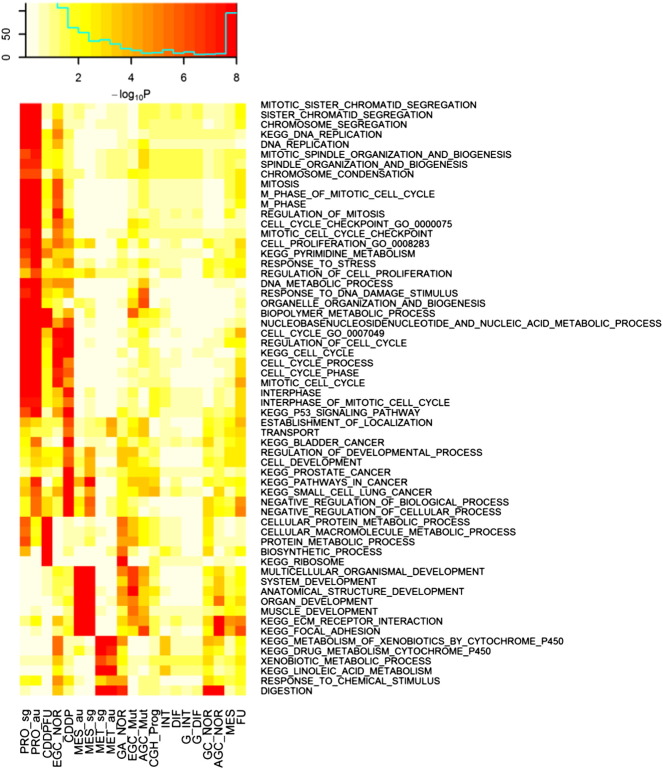

Gene signatures derived from gene expression profiling of tumor samples not only allow us to stratify GC cases as classifier but also enable us a better understanding of the underlying biological process and molecular pathways. Thus, we further examined the enrichment of gene signatures by intersecting these signatures with those gene sets listed in the MSigDB database [60].

The c2 and c5 sets in MSigDB version 5.0, including biological processes and KEGG pathways, respectively, were tested for enrichment in the gene signatures listed in Table 3. The result was represented by the heat map in Fig. 3. Many cancer-associated molecular pathways have been captured in terms of highly overlapped with GC gene signatures. Notably, the digestion and pyrimidine signaling pathways highly enriched in many signatures, indicating they are GC specific and related to inflammation.

Fig. 3.

Enrichment of MSigDB and gastric specific gene sets in the GC gene signatures. The c2 and c5 sets include biological processes and KEGG from MSigDB version 5.0 were employed for enrichment of the analysis of gene sets listed in Table 3.

10. Summary and prospective

The findings from the analysis of gene expression data in GC has a significant impact on our understanding of GC biology by bringing the concept of the heterogeneity of GC to the forefront of GC research and clinical practice [8]. Gene expression profiling technology will enable clinicians not only to estimate the likelihood that certain therapies will be beneficial but also to determine when and how to modify treatment options. More informed decision making will ultimately enable increased rates of response and survival [9,15,26,40,47]. High-throughput molecular techniques will not replace conventional clinical and pathological evaluation to classify GC but rather serve as an adjunct to known clinical methods.

Many gene signatures have been developed, but there is little overlap between those gene lists, and the reproducibility is usually very poor [8]. The poor reproducibility of these models is due to many intrinsic problems associated with heterogeneity in patient populations and tumors and microarray-based approaches. First, patient populations and treatments are diversified: different patient demographics and varied treatment regimens lead to variations into predictive classifiers. Distributions of age, race, and gender have a significant impact on molecular profiling [8]. Therefore, it is difficult to compare expression data from different treatment plans, and such inconsistency limits our ability to develop robust predictive molecular models. Second, the selection of samples is not consistent. Tumors vary in their composition and are highly heterogeneous for stromal and cancerous components. Micro-dissection is often used to ensure that a pure tumor cell population can be profiled. Intriguingly, stromal signatures have been shown to be informative for predicting chemo sensitivity, recurrence, and outcome [61]. Third, there are different profiling platforms and statistical analysis approaches. Biases in profiling platforms and analytic approaches further complicate the reproducibility. Therefore, it is essential that studies are designed and carried out thoughtfully to gain the most appropriate and relevant information. Fourth, there lacks large-scale independent validation. While many studies have used molecular profiling data to develop predictors for predicting treatment response and prognosis in GC, those models share a very limited number of genes. Thus, reliability and reproducibility of microarray data remain questionable unless their performance is confirmed at a relatively large scale.

Recently, several gene microarray-based tools have been commercially developed for clinical use in breast cancer [62,63]. Now the clinical practice of predictive arrays in gastric cancer is falling behind relative to breast cancer. A lot of factors contribute to this lag-behind, but perhaps the first and foremost is the drastically greater volume of research into predictive medicine in breast cancer [63]. Comparing to breast cancer, there are much less common and ongoing controversies in optional multimodality therapy in GC [52]. With more advanced technologies and expanding knowledge from a multitude of existing studies, more accurate subtypes of GC are likely to be teased out from the existing groups. Better characterization of genetic subtypes of gastric cancer may reduce the biological variation and allow the generation of more robust predictive signatures for individual tumor subtypes. Only then will it be possible to apply predictive genomics to clinical practice.

The development and improvement of gene expression assays have led to some major breakthroughs in GC research, which will have the potential to influence the clinical treatment of patients. Although there are significant challenges in implementing genomic medicine in GC [8,64], the future genomic medicine will dramatically reshape how the disease is characterized and defined, how medicine is managed to patients, and how patients are given tailored therapies. The large-scale molecular profiling data in GC at The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provide an excellent opportunity to develop advanced molecular classifiers and predictors for GC diagnosis and treatment.

Author contributions

BZ conceived the idea and supervised the data analysis. BZ and XL wrote the manuscript. XL, YZ, and WS performed data analysis. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Aging (NIA) Award R01AG046170 (to B.Z.); the NIH/National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Award R21MH097156-01A1 (to B.Z.); the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Award R01CA163772 (to B.Z.); and the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Award U01AI111598-01 (to B.Z.).

References

- 1.1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61: 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Siegel R., Naishadham D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen L., Shan Y.S., Hu H.M. Management of gastric cancer in Asia: resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e535–e547. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin J.T. Screening of gastric cancer: who, when, and how. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(1):135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu G.Y., Liu K.H., Zhang Y. Alterations of tumor-related genes do not exactly match the histopathological grade in gastric adenocarcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1129–1137. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu B., El Hajj N., Sittler S. Gastric cancer: classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:251–261. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warneke V.S., Behrens H.M., Hartmann J.T. Cohort study based on the seventh edition of the TNM classification for gastric cancer: proposal of a new staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2364–2371. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brettingham-Moore K.H., Duong C.P., Heriot A.G. Using gene expression profiling to predict response and prognosis in gastrointestinal cancers-the promise and the perils. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1484–1491. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chibon F. Cancer gene expression signatures—the rise and fall? Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2000–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balasubramanian S.P. Evaluation of the necessity for gastrectomy with lymph node dissection for patients with submucosal invasive gastric cancer (Br J Surg 2001; 88: 444–9) Br J Surg. 2001;88:1133–1134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boussioutas A., Li H., Liu J. Distinctive patterns of gene expression in premalignant gastric mucosa and gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2569–2577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vecchi M., Nuciforo P., Romagnoli S. Gene expression analysis of early and advanced gastric cancers. Oncogene. 2007;26:4284–4294. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam S., Lee J., Goh S.H. Differential gene expression pattern in early gastric cancer by an integrative systematic approach. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1675–1682. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Eun JW, Lee H et al. Gene expression changes in patient-matched gastric normal mucosa, adenomas, and carcinomas. Exp Mol Pathol 90: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Lei Z., Tan I.B., Das K. Identification of molecular subtypes of gastric cancer with different responses to PI3-kinase inhibitors and 5-fluorouracil. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:554–565. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlidis N., Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379:1428–1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monzon F.A., Koen T.J. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: molecular approaches for identification of tissue of origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:216–224. doi: 10.5858/134.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greco F.A., Spigel D.R., Yardley D.A. Molecular profiling in unknown primary cancer: accuracy of tissue of origin prediction. Oncologist. 2010;15:500–506. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hainsworth J.D., Rubin M.S., Spigel D.R. Molecular gene expression profiling to predict the tissue of origin and direct site-specific therapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a prospective trial of the Sarah Cannon research institute. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:217–223. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polkowski W., van Sandick J.W., Offerhaus G.J. Prognostic value of Lauren classification and c-erbB-2 oncogene overexpression in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:290–297. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noda S., Soejima K., Inokuchi K. Clinicopathological analysis of the intestinal type and diffuse type of gastric carcinoma. Jpn J Surg. 1980;10:277–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02468788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontana M.G., La Pinta M., Moneghini D. Prognostic value of Goseki histological classification in adenocarcinoma of the cardia. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:401–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee O.J., Kim H.J., Kim J.R., Watanabe H. The prognostic significance of the mucin phenotype of gastric adenocarcinoma and its relationship with histologic classifications. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah M.A., Khanin R., Tang L. Molecular classification of gastric cancer: a new paradigm. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2693–2701. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan I.B., Ivanova T., Lim K.H. Intrinsic subtypes of gastric cancer, based on gene expression pattern, predict survival and respond differently to chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:476–485. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.042. [485 e471-411] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teramoto K., Tada M., Tamoto E. Prediction of lymphatic invasion/lymph node metastasis, recurrence, and survival in patients with gastric cancer by cDNA array-based expression profiling. J Surg Res. 2005;124:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchet A., Mocellin S., Belluco C. Gene expression profile of primary gastric cancer: towards the prediction of lymph node status. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1058–1064. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y.Z., Zhang L.H., Gao Y. Discovery and validation of prognostic markers in gastric cancer by genome-wide expression profiling. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1710–1717. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amini A., Sanati H. Complete pathologic response with combination oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy in an older patient with advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22:1024–1026. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32834a2c16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z., Liu Y., He H. Candidate genes influencing sensitivity and resistance of human glioblastoma to Semustine. Brain Res Bull. 2011;86:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youns M., Fu Y.J., Zu Y.G. Sensitivity and resistance towards isoliquiritigenin, doxorubicin and methotrexate in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cell lines by pharmacogenomics. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;382:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0541-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka T., Tanimoto K., Otani K. Concise prediction models of anticancer efficacy of 8 drugs using expression data from 12 selected genes. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:617–626. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakatsu N., Yoshida Y., Yamazaki K. Chemosensitivity profile of cancer cell lines and identification of genes determining chemosensitivity by an integrated bioinformatical approach using cDNA arrays. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:399–412. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung J.J., Jeung H.C., Chung H.C. In vitro pharmacogenomic database and chemosensitivity predictive genes in gastric cancer. Genomics. 2009;93:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivanova T., Zouridis H., Wu Y. Integrated epigenomics identifies BMP4 as a modulator of cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancer. Gut. 2013;62:22–33. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J.S., Young Yoon S., Kim J.M. Identification of novel genes associated with the response to 5-FU treatment in gastric cancer cell lines using a cDNA microarray. Cancer Lett. 2004;214:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suganuma K., Kubota T., Saikawa Y. Possible chemoresistance-related genes for gastric cancer detected by cDNA microarray. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:355–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H.K., Choi I.J., Kim H.S. DNA microarray analysis of the correlation between gene expression patterns and acquired resistance to 5-FU/cisplatin in gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim H.K., Choi I.J., Kim C.G. A gene expression signature of acquired chemoresistance to cisplatin and fluorouracil combination chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim C.H., Kim H.K., Rettig R.L. miRNA signature associated with outcome of gastric cancer patients following chemotherapy. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J., Yu J.C., Kang W.M., Ma Z.Q. Prognostic significance of intraoperative chemotherapy and extensive lymphadenectomy in patients with node-negative gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:400–404. doi: 10.1002/jso.22089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salem A., Hashem S., Mula-Hussain L.Y. Management strategies for locoregional recurrence in early-stage gastric cancer: retrospective analysis and comprehensive literature review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujiwara M., Kodera Y., Misawa K. Longterm outcomes of early-stage gastric carcinoma patients treated with laparoscopy-assisted surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada Y., Arao T., Gotoda T. Identification of prognostic biomarkers in gastric cancer using endoscopic biopsy samples. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2193–2199. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lo Nigro C., Monteverde M., Riba M. Expression profiling and long lasting responses to chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:1219–1228. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z., Yan Z., Zhang B. Identification of a 5-gene signature for clinical and prognostic prediction in gastric cancer patients upon microarray data. Med Oncol. 2013;30:678. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeno A., Takemasa I., Seno S. Gene expression profile prospectively predicts peritoneal relapse after curative surgery of gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1033–1042. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0854-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho J.Y., Lim J.Y., Cheong J.H. Gene expression signature-based prognostic risk score in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1850–1857. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim M., Rha S.Y. Prognostic index reflecting genetic alteration related to disease-free time for gastric cancer patient. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:421–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stathias V., Pastori C., Griffin T.Z. Identifying glioblastoma gene networks based on hypergeometric test analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willett C.G., Czito B.G. Chemoradiotherapy in gastrointestinal malignancies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim H., Eun J.W., Lee H. Gene expression changes in patient-matched gastric normal mucosa, adenomas, and carcinomas. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;90:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Resende C., Ristimaki A., Machado J.C. Genetic and epigenetic alteration in gastric carcinogenesis. Helicobacter. 2010;15(Suppl. 1):34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng J., Ge Z., Wang L. The histone demethylase RBP2 Is overexpressed in gastric cancer and its inhibition triggers senescence of cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:981–992. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asada K., Ando T., Niwa T. FHL1 on chromosome X is a single-hit gastrointestinal tumor-suppressor gene and contributes to the formation of an epigenetic field defect. Oncogene. 2013;32:2140–2149. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu Y., Liu Z., Guo K. Expression of FHL1 in gastric cancer tissue and its correlation with the invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;363:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cristescu R., Lee J., Nebozhyn M. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 2015;21:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nm.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liberzon A., Subramanian A., Pinchback R. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1739–1740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farmer P., Bonnefoi H., Anderle P. A stroma-related gene signature predicts resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2009;15:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nm.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wesolowski R., Ramaswamy B. Gene expression profiling: changing face of breast cancer classification and management. Gene Expr. 2011;15:105–115. doi: 10.3727/105221611x13176664479241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colombo P.E., Milanezi F., Weigelt B., Reis-Filho J.S. Microarrays in the 2010s: the contribution of microarray-based gene expression profiling to breast cancer classification, prognostication and prediction. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:212. doi: 10.1186/bcr2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCarthy J.J., McLeod H.L., Ginsburg G.S. Genomic medicine: a decade of successes, challenges, and opportunities. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang H.C., Kim I.J., Park J.H. Identification of genes with differential expression in acquired drug-resistant gastric cancer cells using high-density oligonucleotide microarrays. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:272–284. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahn M.J., Yoo Y.D., Lee K.H. cDNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in gastric cancer cells sensitive and resistant to 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin. Cancer Res Treat. 2005;37:54–62. doi: 10.4143/crt.2005.37.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Szoke D., Gyorffy A., Surowiak P. Identification of consensus genes and key regulatory elements in 5-fluorouracil resistance in gastric and colon cancer. Onkologie. 2007;30:421–426. doi: 10.1159/000104490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murakami H., Ito S., Tanaka H. Establishment of new intraperitoneal paclitaxel-resistant gastric cancer cell lines and comprehensive gene expression analysis. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4299–4307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gyorffy B., Surowiak P., Kiesslich O. Gene expression profiling of 30 cancer cell lines predicts resistance towards 11 anticancer drugs at clinically achieved concentrations. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1699–1712. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu H., Li N., Yao L. Prediction of doxorubicin sensitivity in gastric cancers based on a set of novel markers. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:963–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y.H., Wu Q., Xiao X.Y. Silencing MRP4 by small interfering RNA reverses acquired DDP resistance of gastric cancer cell. Cancer Lett. 2010;291:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sohma I., Fujiwara Y., Sugita Y. Parthenolide, an NF-kappaB inhibitor, suppresses tumor growth and enhances response to chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2011;8:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Claerhout S., Lim J.Y., Choi W. Gene expression signature analysis identifies vorinostat as a candidate therapy for gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kato K., Gong J., Iwama H. The antidiabetic drug metformin inhibits gastric cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:549–560. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ooi C.H., Ivanova T., Wu J. Oncogenic pathway combinations predict clinical prognosis in gastric cancer. PLoS Genet. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu Z.Y., Chen J.S., Shu Y.Q. Gene expression profile towards the prediction of patient survival of gastric cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yan Z., Xiong Y., Xu W. Identification of recurrence-related genes by integrating microRNA and gene expression profiling of gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:2166–2174. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yan Z., Xiong Y., Xu W. Identification of hsa-miR-335 as a prognostic signature in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brenner B., Hoshen M.B., Purim O. MicroRNAs as a potential prognostic factor in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3976–3985. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang X., Yan Z., Zhang J. Combination of hsa-miR-375 and hsa-miR-142-5p as a predictor for recurrence risk in gastric cancer patients following surgical resection. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2257–2266. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim M., Chung H.C. Standardized genetic alteration score and predicted score for predicting recurrence status of gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:1501–1512. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0597-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamaguchi U., Nakayama R., Honda K. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4100–4108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leung S.Y., Yuen S.T., Chu K.M. Expression profiling identifies chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 as an independent prognostic indicator in gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:457–469. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen C.N., Lin J.J., Chen J.J. Gene expression profile predicts patient survival of gastric cancer after surgical resection. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7286–7295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Setoguchi T., Kikuchi H., Yamamoto M. Microarray analysis identifies versican and CD9 as potent prognostic markers in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:883–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Deng N., Goh L.K., Wang H. A comprehensive survey of genomic alterations in gastric cancer reveals systematic patterns of molecular exclusivity and co-occurrence among distinct therapeutic targets. Gut. 2012;61:673–684. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wong S.S., Kim K.M., Ting J.C. Genomic landscape and genetic heterogeneity in gastric adenocarcinoma revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5477. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kakiuchi M., Nishizawa T., Ueda H. Recurrent gain-of-function mutations of RHOA in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:583–587. doi: 10.1038/ng.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]