Abstract

Functional neuroplasticity in response to stimulation and motor training is a well-established phenomenon. Transcutaneous stimulation of the spine is used mostly to alleviate pain, but it may also induce functional neuroplasticity, because the spinal cord serves as an integration center for descending and ascending neuronal signals. In this work, we examined whether long-lasting noninvasive cathodal (c-tsCCS) and anodal (a-tsCCS) transspinal constant-current stimulation over the thoracolumbar enlargement can induce cortical, corticospinal, and spinal neuroplasticity. Twelve healthy human subjects, blind to the stimulation protocol, were randomly assigned to 40 min of c-tsCCS or a-tsCCS. Before and after transspinal stimulation, we established the afferent-mediated motor evoked potential (MEP) facilitation and the subthreshold transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)-mediated flexor reflex facilitation. Recruitment input-output curves of MEPs and transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) and postactivation depression of the soleus H reflex and TEPs was also established. We demonstrate that both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS decrease the afferent-mediated MEP facilitation and alter the subthreshold TMS-mediated flexor reflex facilitation in a polarity-dependent manner. Both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS increased the tibialis anterior MEPs recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold, intermediate, and maximal intensities and altered the recruitment input-output curve of TEPs in a muscle- and polarity-dependent manner. Soleus H-reflex postactivation depression was reduced after a-tsCCS and remained unaltered after c-tsCCS. No changes were found in the postactivation depression of TEPs after c-tsCCS or a-tsCCS. Our findings reveal that c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS have distinct effects on cortical and corticospinal excitability. This method can be utilized to induce targeted neuroplasticity in humans.

Keywords: brain stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, neuroplasticity, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transspinal evoked potential, motor evoked potential

the brain and spinal cord are prone to functional and structural changes that can occur in distributed neural networks underlying motor behavior (Joseph 2013). Neuronal plasticity can be induced via repetitive, paired, or continuous electrical stimulation (Rossini et al. 2015). For example, high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), repetitive TMS paired with peripheral nerve stimulation at long interstimulus intervals, and repetitive paired TMS pulses at I-wave periodicity increase motor evoked potential (MEP) sizes and thus potentiate corticospinal excitability (Pascual-Leone et al. 1994; Stefan et al. 2000; Thickbroom et al. 2006). Similarly, low-frequency repetitive TMS and TMS paired with peripheral nerve stimulation at shorter intervals have depressant effects on corticospinal excitability (Chen et al. 1997; Wolters et al. 2003). Possible mechanisms accounting for these neurophysiological changes are those underlying learning and memory, known as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) (Dan and Poo 2006; Rioult-Pedotti et al. 2000; Stefan et al. 2002).

Corticomotoneuronal connections have a systematic synaptic pattern with alpha motoneurons (Bawa and Lemon 1993; Edgley et al. 1997), and corticospinal systems corresponding to each leg interact at the spinal level (Brus-Ramer et al. 2009). These potent characteristics of corticomotoneuronal connections along with their distinct ability to change after electrical stimulation (Carmel et al. 2010) support the notion that long-lasting stimulation of the spinal cord can influence cortical and corticospinal excitability. In anesthetized spinal cats, polarizing currents passed across the spinal cord in a dorsal-ventral direction alter the amplitude of membrane potentials and the excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) of spinal motoneurons (Eccles et al. 1962). Furthermore, repetitive stimulation produces hyperpolarization of nerve terminals, thereby enhancing synaptic transmission via postactivation potentiation (Hubbard and Willis 1962).

Electrical stimulation delivered epidurally or transcutaneously to the spinal cord generates compound action potentials or transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) in arm and leg muscles with distinct neurophysiological characteristics (Einhorn et al. 2013; Knikou 2013a, 2013b, 2014; Maruyama et al. 1982). TEPs are mediated mostly by direct nonsynaptic activation of motoneurons and indirect transsynaptic excitation of descending projections and local spinal interneuron circuits (Maruyama et al. 1982; Sharpe and Jackson 2014). In people with spinal cord injury, current delivered transcutaneously or via epidural stimulation increases motor activity of paralyzed muscles (Harkema et al. 2011; Jilge et al. 2004), induces rhythmic locomotor-like motor activity (Minassian et al. 2007), and entrains output of previously silent muscles during robotic-driven assisted stepping (Minassian et al. 2015). These modulatory effects on motor output can be mediated by plastic changes in a network(s) of cortical or spinal circuits, but it is not known whether long-lasting noninvasive transspinal stimulation can induce neuroplasticity.

We have demonstrated that the transspinal stimulation-induced TEPs in arm and leg muscles are increased when the excitability of peripheral nerves is altered or when descending and ascending inputs are synchronized to meet at the spinal cord (Einhorn et al. 2013; Knikou 2013a, 2013b, 2014). On the basis of these findings, we hypothesized that transspinal stimulation induces cortical, corticospinal, and spinal neuroplasticity. To test our hypotheses, we delivered cathodal (c-tsCCS) and anodal (a-tsCCS) transspinal constant-current stimulation for 40 min. Cortical neuroplasticity was assessed based on changes in the amount of afferent-mediated MEP facilitation and subthreshold TMS-mediated flexor reflex facilitation. Corticospinal neuroplasticity was assessed based on changes in the amplitude of resting MEPs and MEP recruitment input-output curves. Spinal plasticity was assessed based on changes in the amplitude of resting TEPs, recruitment curves of TEPs, and amount of soleus H-reflex and TEP postactivation depression. Part of this study has been published in abstract form (Knikou et al. 2015).

METHODS

Subjects

Twelve healthy subjects (5 men, 7 women; 24 ± 1.67 yr, mean age ± SD) with right leg dominance participated in this study. All subjects gave their written consent to the experimental procedures, which were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki after full Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval by the City University of New York IRB committee. Subjects with tooth implants, metal implants in the body, assistive hearing devices, pacemaker, history of seizures, or history of depression and those who were taking medications known to alter central nervous system (CNS) excitability were excluded from the study. The blood pressure of all participants was monitored periodically during the experiments, and no significant changes were noted. MEPs and spinal reflexes were recorded with subjects seated (hip angle, 120°; knee angle, 160°; ankle angle, 110°) with both feet supported by foot rests. Transspinal stimulation was delivered with subjects supine. Both knee joints were flexed at 30°, and ankle joints were supported by foot rests positioned in neutral. The supine position was selected because TEP amplitude depends on the position of the body (Danner SM, Krenn M, personal communication).

Recordings.

In all subjects, electromyography (EMG) was recorded bilaterally from the medial gastrocnemius (MG), soleus (SOL), tibialis anterior (TA), rectus femoris (RF), vastus medialis (VM), medial hamstrings (MH), and hip adductor gracilis (GRC) muscles via single bipolar differential electrodes (MA300-28, Motion Lab Systems, Baton Rouge, LA). EMG signals were amplified, filtered (10-1,000 Hz), sampled at 2,000 Hz (1401 plus running Spike 2, Cambridge Electronics Design), and stored as coded data files on a password-protected personal computer for off-line analysis.

Stimulation

Transcranial.

Single TMS pulses over the left primary motor cortex were delivered with a Magstim 2002 stimulator (Magstim) with a double-cone coil (diameter 110 mm) placed so the current of the coil flowed from a posterior to an anterior direction. Procedures were similar to those we have previously utilized (Hanna-Boutros et al. 2015; Knikou 2014; Knikou et al. 2013). The point where the lines between the inion and glabellum and the left and right ear tragus met was marked on an EEG cap. The center of the double-cone coil was placed 1 cm posterior to and 1 cm to the left of this intersection point. With the double-cone coil held at this position, the stimulation intensity was gradually increased from zero and MEPs recorded from the right TA, SOL, and MG muscles were observed on a digital oscilloscope. When TA MEPs could not be evoked at low stimulation intensities with the subject at rest in three of five consecutive TMS pulses, the magnetic coil was moved by a few millimeters to the left and the procedure was repeated. When the optimal position was determined, the TA MEP resting threshold was established and corresponded to the lowest stimulation intensity that induced repeatable MEPs with peak-to-peak amplitude of at least 100 μV in three of five consecutive single TMS pulses (Rossini et al. 2015). All subjects wore a mouth guard and earplugs to minimize discomfort due to TMS. Subjects answered a post-TMS questionnaire the day after the experiment. A few subjects reported mild but short-lived headaches.

Transspinal.

TEPs in leg muscles were elicited via a single cathode electrode (Uni-Patch EP84169, 10.2 cm × 5.1 cm, Wabasha, MA) placed along the vertebrae equally between the left and right paravertebral sides. The T10 spinous process was identified via palpation. Because of its size, the electrode covered from T10 to L2 vertebral levels. These vertebral levels correspond to L1 to S2 spinal segments and thus to the segmental innervation of the muscles from which TEPs were recorded in this study (Kendall et al. 1993). Two reusable self-adhered electrodes (anode; same type as the cathode), connected to function as a single electrode, were placed on the left and right iliac crests. The cathode and anode electrodes were connected to a constant-current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK) that was triggered by Spike 2 scripts. The cathode electrode was held under constant pressure throughout the experiment and maintained in place via Pre-Wrap.

Posterior tibial nerve.

A stainless steel plate electrode (anode) 4 cm in diameter was placed and secured proximal to the right patella. Rectangular single-pulse stimuli of 1 ms were delivered to the tibial nerve at the popliteal fossa. The most optimal stimulation site was established via a handheld monopolar stainless steel head electrode used as a probe (Knikou 2008). An optimal stimulation site corresponded to the site at which the M wave had a shape similar to that of the H reflex at low and high stimulation intensities, and at low stimulus intensities an H reflex could be evoked without an M wave (Knikou 2008). When the optimal site was identified, the monopolar electrode was replaced by a pregelled disposable electrode (cathode; Suretrace, Conmed, Utica, NY) that was maintained under constant pressure throughout the experiment.

Medial arch of the foot.

The medial arch of the right foot was stimulated with a 30-ms pulse train with a constant-current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer) at a site at which at the lowest stimulation intensities TA responses in the right leg were evoked, with absent responses in the ipsilateral SOL and/or MG muscles. The bipolar electrode was replaced by two disposable pregelled Ag-AgCl electrodes (Suretrace adhesive gel electrodes; Conmed) that were maintained in place via Pre-Wrap. The TA flexor reflex behavior in response to low and high stimulation intensities was reestablished, and the lowest stimulus intensity that induced an initial EMG response in the right TA muscle was identified as reflex threshold.

Transspinal Stimulation for Neuroplasticity

Eligible participants received randomly c-tsCCS (n = 11) or a-tsCCS (n = 9) on two different days at least 4 wk apart. c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS were delivered for 40 min (480 single 1-ms pulses at 0.2 Hz) at similar intensities (c-tsCCS: 61.2 ± 4.73 mA; a-tsCCS: 64.4 ± 4.86 mA). The stimulation intensity was selected based on the amplitude of the TA and SOL TEPs. Specifically, the TA TEPs were matched to be equivalent to the TA MEPs recorded at 1.2 resting MEP threshold, and the SOL TEPs were matched to be equivalent to the soleus H reflex that was ∼20–30% of the maximal M wave. Electrodes were positioned in a manner similar to that utilized to evoke TEPs in both leg muscles. However, the polarity of the electrodes was switched to deliver either c-tsCCS or a-tsCCS through a single electrode to the thoracolumbar enlargement.

Neurophysiological Tests Conducted Before and After c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS

The neurophysiological tests described below were conducted before and after transspinal stimulation randomly within and across subjects. The time at which each neurophysiological test was conducted after 40 min of c-tsCCS or a-tsCCS varied significantly and ranged from 15 to 60 min after transspinal stimulation.

Cortical neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity at the cortical level was assessed by establishing changes in the amounts of 1) afferent-mediated TA MEP facilitation and 2) subthreshold TMS-mediated TA flexor reflex facilitation (Fig. 1A). Stimulation of mixed peripheral nerves delivered 20–50 ms before TMS induces a significant facilitation of MEPs (Kasai et al. 1992; Khaslavskaia et al. 2002; Mariorenzi et al. 1991; Nielsen et al. 1997) that coincides with absent changes in soleus H reflex and cervicomedullary evoked potentials (Mariorenzi et al. 1991; Roy and Gorassini 2008). Thus afferent-mediated facilitation of MEPs is mostly cortical in origin. The medial arch of the foot, stimulated at twofold sensory threshold, preceded the TMS pulses at the conditioning-test (C-T) intervals of 0, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 ms. The C-T intervals correspond to the time between the onset of the conditioning pulse train to the medial arch of the foot and the onset of the TMS test stimulus. Across subjects, control and conditioned MEPs were recorded randomly at 1.2 ± 0.009 (47.45 ± 2.16% maximum stimulator output) resting MEP threshold for c-tsCCS and at 1.28 ± 0.03 (46.78 ± 2.53% maximum stimulator output) resting MEP threshold for a-tsCCS. Under control conditions and at each C-T interval, 15 TA MEPs were recorded at a stimulation frequency of 0.1 Hz.

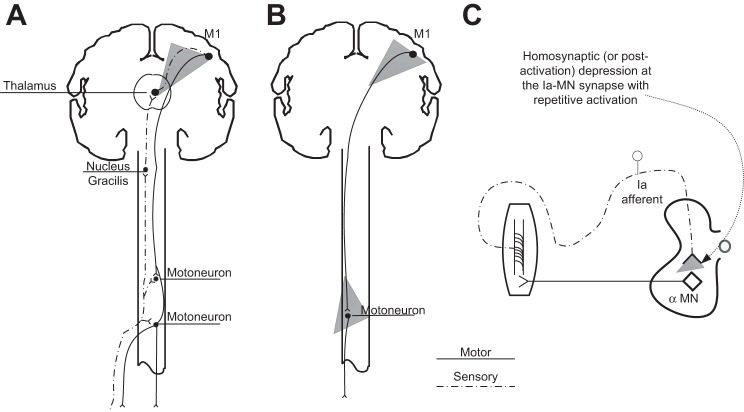

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagrams of the neuronal pathways/circuits undergoing neuroplastic changes after long-lasting transspinal stimulation. A: afferent-mediated tibialis anterior (TA) motor evoked potential (MEP) facilitation and subthreshold transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)-mediated flexor reflex facilitation were established to assess cortical plasticity. B: changes in the TA MEP recorded at 1.2 TA MEP resting threshold and TA recruitment input-output curves were established to assess corticospinal plasticity. C: postactivation depression of the soleus H reflex and transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) was established to assess spinal plasticity. MN, motoneuron. Gray filled triangles indicate the site for each neurophysiological test conducted to probe neuroplasticity.

TMS delivered at an intensity that does not evoke direct depolarization of spinal α-motoneurons modulates segmental spinal reflexes, ongoing EMG activity, and MEPs mostly through cortical interneuronal circuits because descending spinal cord volleys are suppressed upon paired TMS (Di Lazzaro et al. 1998). Subthreshold TMS increases the polysynaptic spinal TA flexor reflex size when TMS pulses are delivered 40–100 ms after the end of the test pulse train stimulation (Mackey et al. 2015). By convention these intervals are negative. Furthermore, at the negative C-T intervals of 40–80 ms, the delay is sufficient for the interaction between conditioning TMS and test afferent volleys to occur at the somatosensory cortex.

In this study, subthreshold conditioning TMS was delivered at 0.7 ± 0.005 TA MEP resting threshold for c-tsCCS and at 0.71 ± 0.009 TA MEP resting threshold for a-tsCCS. The effects of subthreshold TMS on the innocuous TA flexor reflex evoked by medial arch foot stimulation were established at C-T intervals that ranged from −80 ms (TMS delivered after foot stimulation) to 20 ms (TMS delivered before foot stimulation). Flexor reflexes for c-tsCCS were elicited at 1.36 ± 0.07 and for a-tsCCS at 1.50 ± 0.12 TA flexor reflex threshold. Under control conditions and for each C-T interval, 10 TA flexor reflexes at a stimulation frequency of 0.1 Hz were recorded.

Corticospinal neuroplasticity.

Corticospinal neuroplasticity after transspinal stimulation was assessed by establishing changes in the TA MEP recorded at 1.2 TA MEP resting threshold and from changes in the TA MEP recruitment curve (Fig. 1B). For each subject, the TA MEP recruitment curve was assembled starting from stimulation intensities corresponding to 0.6 TA MEP resting threshold until maximal amplitudes were obtained. TA MEPs for both cases were recorded at similar stimulation intensities for each subject before and after a-tsCCS and c-tsCCS.

Spinal neuroplasticity.

Spinal neuroplasticity was assessed by establishing changes in the 1) TEP recruitment curves and 2) amount of soleus H-reflex and TEP postactivation depression (Fig. 1C). TEPs in response to cathodal transspinal stimulation were recorded at interstimulus intervals of 5 s and 1 s and at different intensities to assemble the TEP input-output recruitment curve. At the intensity at which most TEPs of ankle muscles were 30% of their maximal amplitude, 10 TEPs elicited every 5 s (or 0.2 Hz) or every 1 s (1 Hz) were recorded. For each recruitment curve assembled, at least 80 TEPs at different stimulation intensities were recorded. To establish the soleus H-reflex postactivation depression, the maximal M wave following posterior tibial nerve stimulation was evoked, measured as peak-to-peak amplitude, and saved for off-line analysis. The stimulus intensity was then adjusted to evoke an H reflex on the ascending part of the recruitment curve that ranged from 20% to 40% of the maximal M wave across subjects (Knikou 2008). Twenty soleus H reflexes were recorded randomly at interstimulus intervals of 5 s and 1 s, as well as upon paired pulses at an interstimulus interval of 50 ms and a stimulation frequency of 0.2 Hz.

Off-Line Data Analysis

MEPs, TEPs, M waves, H reflexes, and flexor reflexes were measured as the area of the full-wave-rectified EMG signal (Spike 2, Cambridge Electronics Design). The latency of the TA MEP and TEP of each muscle was measured based on the cumulative sum technique on the rectified waveform average (Brinkworth and Türker 2003; Ellaway 1978; Knikou 2014).

For each subject, the TA MEP recorded at different stimulation intensities (recruitment curve) was normalized to the maximal associated MEP size recorded before 40 min of transspinal stimulation. A Boltzmann sigmoid function (Eq. 1) was fitted to all recorded normalized MEPs plotted against the stimulation intensity. The MEP slope and stimuli corresponding to MEP threshold and maximal MEP were estimated based on Eqs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The predicted MEP threshold intensity was used to normalize the TMS intensities. This was done for each subject separately so that MEP amplitudes at different stimulation intensities could be grouped across subjects based on multiples of MEP resting threshold. The average normalized MEP size was calculated in steps of 0.05 MEP resting threshold for each subject and then across subjects. This was done separately for MEPs recorded before and after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS and for TEP recruitment curves recorded bilaterally from distal and proximal leg muscles.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The soleus H reflex recorded at 0.2 Hz and at 1 Hz and upon paired pulses at 0.2 Hz was normalized to the associated maximal M wave. TA MEPs conditioned by sensory stimulation and TA flexor reflexes conditioned by subthreshold TMS were normalized to the unconditioned associated control value. The average amplitude of the conditioned MEPs or flexor reflexes from each subject was grouped based on time, C-T interval, and transspinal stimulation polarity.

Statistics

Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) was performed to determine the effect of time and C-T interval on the overall amplitude of TA MEPs conditioned by cutaneous stimulation. Two-way RM ANOVA was performed to determine the effect of time and C-T interval on the overall amplitude of TA flexor reflexes conditioned by subthreshold TMS. Three-way RM ANOVA was performed to establish the effect of polarity, time, and C-T interval on the MEPs conditioned by cutaneous stimuli and on the flexor reflexes conditioned by subthreshold TMS. The same analysis was performed to assess the effects of polarity, time, and muscle on the percent change of TEPs and soleus H reflexes recorded at different stimulation frequencies. Post hoc Bonferroni, Holm-Sidak, or Student-Newman-Keuls t-tests for multiple comparisons were used to test for significant differences between polarity, time, muscle, and C-T interval. Additional ANOVA and paired t-tests or rank sum tests were performed for each group and between groups as needed. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Group data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Cortical Plasticity After Transspinal Stimulation: Afferent-Mediated MEP Facilitation

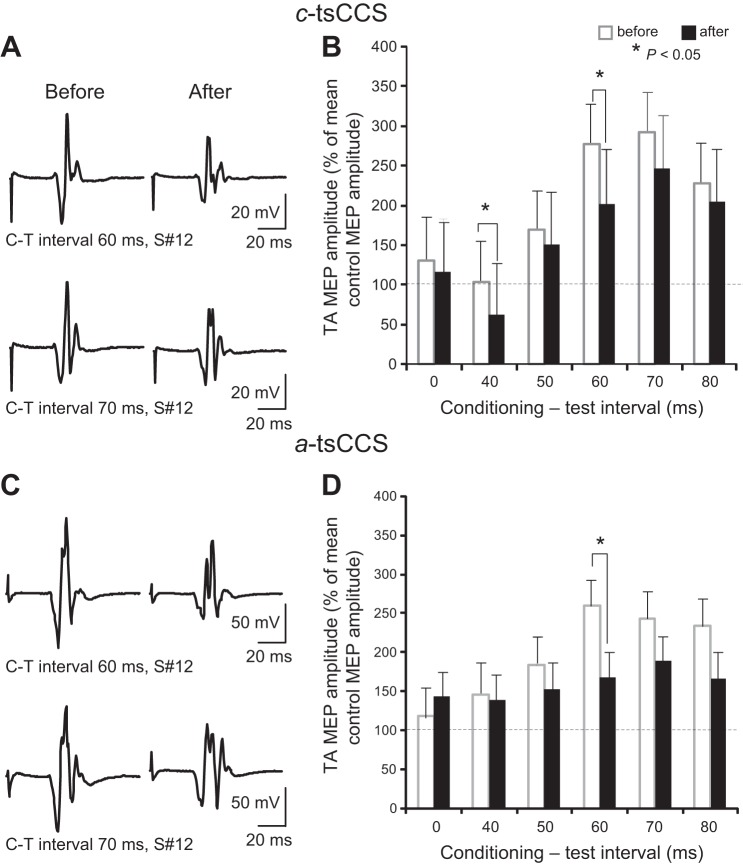

Figure 2, A and C, illustrate waveform averages (n = 15) of MEPs from one representative participant (subject 12) recorded at intervals at which sensory foot stimulation was delivered 60 or 70 ms before TMS after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS. Note that the size of TA MEPs decreased regardless of stimulus polarity.

Fig. 2.

Cortical plasticity after transspinal stimulation: afferent-mediated MEP facilitation. A and C: nonrectified waveform averages of TA MEPs conditioned by sensory stimulation from a representative subject [subject (S#)12] before and after 40 min of cathodal (c-tsCCS) and anodal (a-tsCCS) transspinal constant-current stimulation. C-T interval, conditioning-test interval. B and D: overall amplitude of TA MEPs conditioned by sensory stimulation from all subjects. x-Axis shows the C-T interval between the conditioning sensory stimulation and the test TMS. y-Axis shows the TA MEP as % of the control MEP size. Error bars indicate SE.

In the c-tsCCS group, the conditioned TA MEP amplitude was significantly different based on time of testing [F(1,4) = 8.76, P = 0.004] and C-T interval [F(1,4) = 10.02, P < 0.001] (Fig. 2B). Specifically, the conditioned TA MEPs were significantly reduced after c-tsCCS compared with those observed before c-tsCCS at C-T intervals of 40 and 60 ms (Fig. 2B). In the a-tsCCS group, the conditioned MEP amplitude from all subjects was significantly different based on time of testing [F(1,4) = 8.76, P = 0.004] and C-T interval [F(1,4) = 10.02, P < 0.001]. The conditioned TA MEPs from all subjects were significantly reduced after a-tsCCS at the C-T interval of 60 ms (Fig. 2D). For c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS groups, three-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of time [F(1,4,1) = 8, P < 0.001] and C-T interval [F(1,4,1) = 10.02, P < 0.001] but not of stimulation polarity [F(1,4,1) = 0.134, P = 0.71]. However, post hoc Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons revealed that at C-T intervals of 40 ms (t = 3.17, P = 0.002), 50 ms (t = 3.84, P < 0.001), and 60 ms (t = 3.18, P = 0.002) the effect of a-tsCCS was stronger compared with that of c-tsCCS.

Cortical Plasticity After Transspinal Stimulation: TMS-Mediated Flexor Reflex Facilitation

Figure 3, A and C, illustrate waveform averages (n = 10) of conditioned TA flexor reflexes from two representative subjects (subjects 7 and 10) at an interval that subthreshold TMS was delivered 60 ms after medial arch foot stimulation before and after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS. Note that the amplitude of the conditioned TA flexor reflexes for both participants was increased after c-tsCCS but decreased after a-tsCCS.

Fig. 3.

Cortical plasticity after transspinal stimulation: subthreshold TMS-mediated flexor reflex facilitation. A and C: nonrectified waveform averages of TA flexor reflexes conditioned by subthreshold TMS in 2 representative subjects (subjects 7 and 10) before and after 40 min of c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS. B and D: overall amplitude of TA flexor reflexes conditioned by subthreshold TMS from all subjects. x-Axis shows the C-T interval between the conditioning subthreshold TMS and medial arch test stimulation. y-Axis shows TA flexor reflex size as % of control reflex values. Error bars indicate SE.

In the c-tsCCS group, the conditioned TA flexor reflex amplitude from all subjects was significantly different based on time of testing [F(1,7) = 8.27, P = 0.005] and C-T interval [F(1,7) = 6.75, P < 0.001], but an interaction between them was not found [F(1,7) = 0.31, P = 0.94]. Post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls tests for multiple comparisons revealed that the overall amplitude of the conditioned TA flexor reflexes was increased at the C-T intervals of −80, −70, −60, and −50 ms after c-tsCCS (Fig. 3B). In the a-tsCCS group, the conditioned TA flexor reflex amplitude from all subjects was significantly different based on time of testing [F(1,5) = 6.37, P = 0.013] and C-T interval [F(1,5) = 3.78, P = 0.004], but an interaction between them was not found [F(1,5) = 0.34, P = 0.88]. Post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls tests for multiple comparisons revealed that the TA flexor reflex facilitation at the C-T interval of −50 ms was reduced after a-tsCCS compared with that observed before a-tsCCS (Fig. 3D).

For c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS groups, three-way RM ANOVA showed a significant effect of polarity [F(1,1,5) = 12.55, P < 0.001] and C-T interval [F(1,1,5) = 8.96, P < 0.001] and an interaction between time and polarity [F(1,1,5) = 17.91, P < 0.001]. On the basis of these results, it is evident that c-tsCCS potentiates facilitation of TA flexor reflexes by subthreshold TMS while a-tsCCS decreases this facilitation.

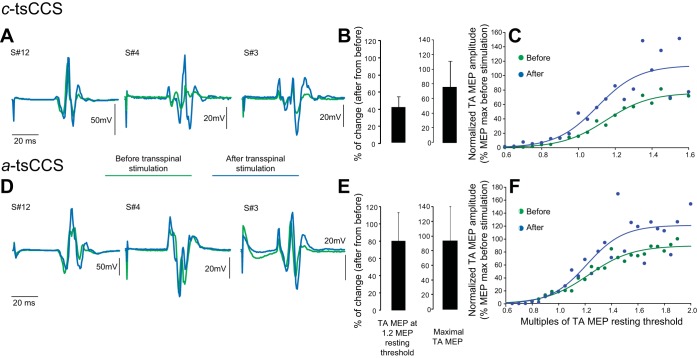

Corticospinal Plasticity After Transspinal Stimulation

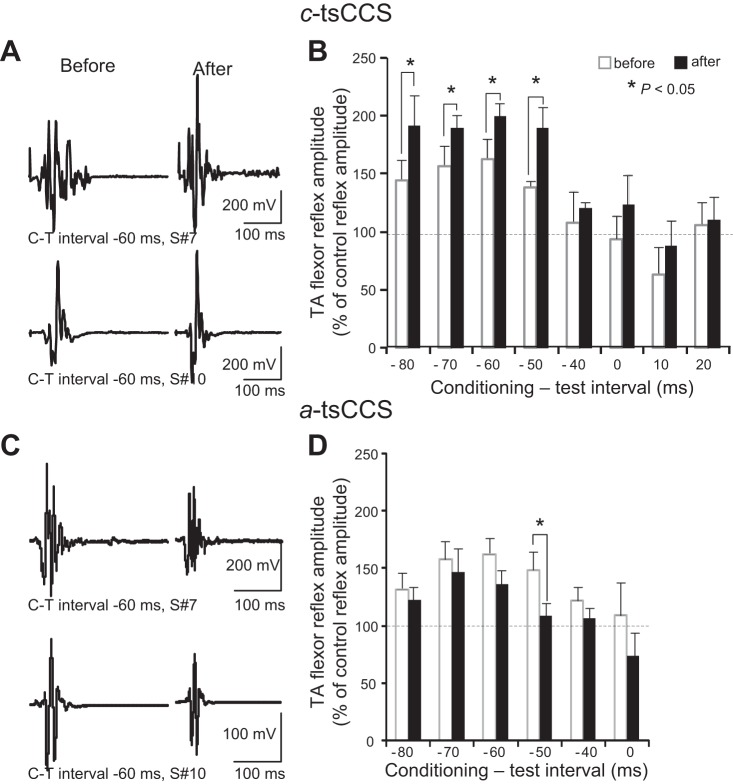

The latency of the TA MEP recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold did not change in the c-tsCCS (before: 31.24 ± 0.78 ms, after: 31.15 ± 0.71 ms; P = 0.46) or a-tsCCS (before: 31.56 ± 0.76 ms, after: 31.43 ± 0.79 ms; P = 0.45) group. Figure 4, A and D, illustrate nonrectified waveform averages of TA MEPs recorded at 1.2 TA MEP resting threshold from three representative participants (subjects 12, 4, and 3) before and after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS. Note that both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS increased the MEP amplitude.

Fig. 4.

Corticospinal plasticity after transspinal stimulation. A and D: nonrectified waveform averages of TA MEPs recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold before and after 40 min of transspinal stimulation. B and E: % of change of TA MEPs at 1.2 MEP resting threshold and % of change of maximal MEP sizes from all subjects of each group before and after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS. C and F: TA MEP recruitment curves from all subjects of each group before and after transspinal stimulation. x-Axis shows multiples of TA MEP resting threshold. y-Axis shows TA MEP sizes as % of the associated maximal MEP size obtained before transspinal stimulation.

The TA MEP amplitude recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold from all subjects increased by 41.03 ± 12.38% and the maximal MEP amplitude increased by 74.31 ± 34.74% after c-tsCCS (Fig. 4B). The TA MEP recruitment curves support increased corticospinal excitability of the leg motor cortex area after c-tsCCS (Fig. 4C). RM ANOVA showed that the actual normalized MEP amplitudes recorded at different intensities changed significantly as a function of time [F(1,11) = 11.95, P < 0.001] for stimulation intensities of 55%, 60%, and 70%, which correspond largely to 1.2 MEP resting threshold intensities. The predicted maximal MEP amplitude from the sigmoid function fitted to each MEP recruitment curve separately changed from 97.79 ± 8.3% before c-tsCCS to 164.3 ± 27.7% after c-tsCCS (t = 91, P = 0.021).

In the a-tsCCS group, the average TA MEP amplitude recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold from all subjects increased by 80 ± 33.14% and the maximal MEP amplitude increased by 85.08 ± 42.51% (Fig. 4E). The TA MEP recruitment curves before and after a-tsCCS from all subjects support increased corticospinal excitability of the leg motor cortex area (Fig. 4F). The predicted maximal MEP from the sigmoid function fitted to each MEP recruitment curve separately changed from an overall mean amplitude of 113.21 ± 9.97% before a-tsCCS to 146.96 ± 24.9% after a-tsCCS (t = 77, P = 0.48). However, RM ANOVA showed that the actual normalized MEP amplitudes recorded at different intensities changed significantly as a function of time [F(1,14) = 41.09, P < 0.001] for stimulation intensities of 67 up to 85 (in increments of 3), which largely correspond to intensities of 1.3 MEP resting threshold and maximal MEPs.

For c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS groups, two-way RM ANOVAs on the MEP recruitment curve sigmoid function parameters showed a significant effect of polarity [F(1,1) = 7.022, P = 0.012] but not of time [F(1,1) = 1.37, P = 0.24] for m function, a significant effect of polarity [F(1,1) = 8.19, P = 0.007] but not of time [F(1,1) = 0.8, P = 0.37] for MEP slope, a nonsignificant effect of polarity [F(1,1) = 0.27, P = 0.6] and time [F(1,1) = 2.53, P = 0.24] for stimuli at MEP threshold, a significant effect of polarity [F(1,1) = 7.59, P = 0.009] but not of time [F(1,1) = 0.083, P = 0.77] for stimuli at MEP maximal, and a nonsignificant effect of polarity [F(1,1) = 0.001, P = 0.96] but a significant effect of time [F(1,1) = 6.17, P = 0.01] for maximal MEP amplitude.

Spinal Plasticity After Transspinal Stimulation: Recruitment Curves of TEPs

TEPs were present at similar latencies in left and right leg muscles, with shorter latencies observed for the RF and MH muscles compared with the more distal ankle flexors/extensors (Table 1), consistent with the TEP latencies we have previously reported (Knikou 2013a, 2013b). The latency of TEPs tested in all leg muscles at an interstimulus interval of 5 s did not change before and after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS (for all TEP latencies before and after P > 0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Latency of transspinal evoked potentials before and after 40 min of transspinal stimulation

| R TA | R MG | R SOL | R RF | R MH | R GRC | R VM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-tsCCS | |||||||

| Before | 15.58 ± 0.5 | 16.97 ± 0.79 | 19.51 ± 0.58 | 11.74 ± 1.36 | 12.54 ± 0.37 | 12.63 ± 0.67 | 9.60 ± 0.58 |

| After | 15.46 ± 0.59 | 16.48 ± 0.64 | 20.04 ± 0.55 | 10.46 ± 0.65 | 12.79 ± 0.37 | 12.44 ± 0.64 | 9.67 ± 0.57 |

| a-tsCCS | |||||||

| Before | 16.97 ± 0.89 | 18.08 ± 1.02 | 19.54 ± 0.87 | 12.88 ± 1.12 | 13.22 ± 0.33 | 14.04 ± 0.64 | 10.24 ± 0.78 |

| After | 16.35 ± 1.03 | 17.64 ± 0.91 | 19.06 ± 0.76 | 11.13 ± 0.96 | 13.25 ± 0.59 | 15.13 ± 0.17 | 9.66 ± 0.73 |

| L TA | L MG | L SOL | L RF | L MH | L GRC | L VM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-tsCCS | |||||||

| Before | 15.36 ± 0.45 | 17.16 ± 0.50 | 19.14 ± 0.65 | 10.89 ± 0.81 | 12.64 ± 0.33 | 12.28 ± 0.65 | 9.28 ± 0.38 |

| After | 15.57 ± 0.66 | 17.65 ± 0.76 | 18.98 ± 0.72 | 10.97 ± 0.93 | 12.71 ± 0.21 | 12.07 ± 0.86 | 9.16 ± 0.40 |

| a-tsCCS | |||||||

| Before | 16.81 ± 0.86 | 17.52 ± 0.61 | 19.98 ± 0.71 | 9.13 ± 0.71 | 12.53 ± 0.91 | 11.15 ± 0.68 | 9.95 ± 0.70 |

| After | 16.18 ± 0.79 | 17.68 ± 0.78 | 20.05 ± 0.53 | 9.73 ± 0.97 | 12.90 ± 0.57 | 12.68 ± 0.81 | 9.84 ± 0.53 |

Values (in ms) are means ± SE.

c-tsCCS, a-tsCCS, cathodal and anodal transspinal constant-current stimulation; R, right; L, left; TA, tibialis anterior; MG, medial gastrocnemius; SOL, soleus; RF, rectus femoris; MH, medial hamstrings; GRC, hip adductor gracilis; VM, vastus medialis.

Latencies before and after transspinal stimulation for all transspinal evoked potentials P > 0.05.

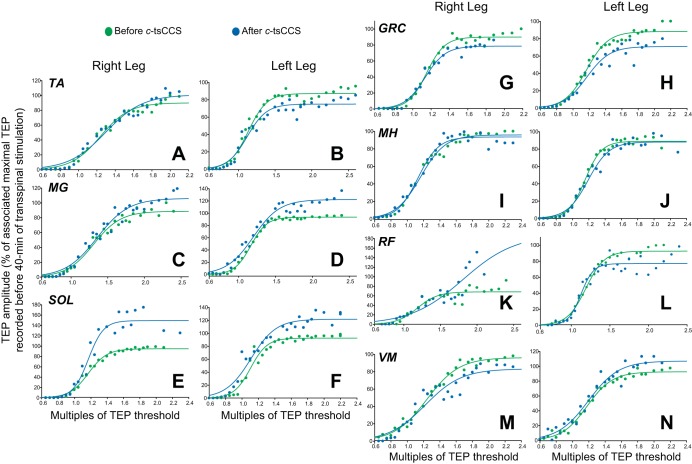

Figure 5 illustrates the mean TEP amplitude from all subjects and muscles at different intensities (recruitment curves) before and after c-tsCCS. For TEPs recorded from right leg muscles, c-tsCCS changed the recruitment order and increased the predicted maximal amplitude based on the sigmoid function fit for the SOL (P = 0.03; Fig. 5E) and RF (P = 0.04; Fig. 5K) and decreased for the hip adductor GRC (P = 0.007; Fig. 5G). For TEPs recorded from left leg muscles, c-tsCCS changed the recruitment and increased the predicted maximal amplitude based on the sigmoid function fit for the MG (P = 0.04; Fig. 5D) and SOL (P = 0.04; Fig. 5F) and decreased for the TA (P = 0.02; Fig. 5B) and GRC (P = 0.02; Fig. 5H).

Fig. 5.

Spinal plasticity after c-tsCCS. TEP recruitment curves: recruitment input-output curves of TEPs recorded bilaterally from the TA, medial gastrocnemius (MG), soleus (SOL), gracilis (GRC), medial hamstrings (MH), rectus femoris (RF), and vastus medialis (VM) muscles from all subjects. x-Axis shows multiples of TEP resting threshold. y-Axis shows TEP sizes as % of the associated maximal TEP size obtained before transspinal stimulation.

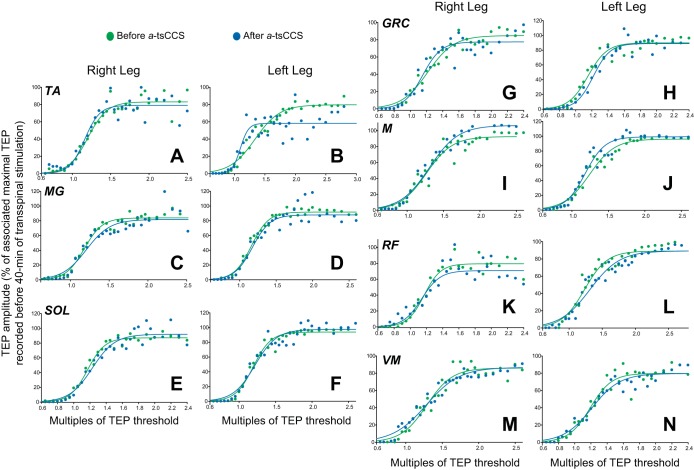

Figure 6 illustrates the mean TEP amplitude from all subjects and muscles at different intensities (recruitment curves) before and after a-tsCCS. No significant changes in the recruitment order or maximal TEP amplitudes were found for TEPs recorded from the right leg muscles (P > 0.05). A tendency for a-tsCCS to negatively affect the recruitment of the left MG and SOL TEPs was noted (Fig. 6, D and F). However, a statistically significant difference between the predicted maximal TEP amplitudes before and after stimulation was not found (P > 0.05). A nonsignificant effect of time was found for the sigmoid function m (P = 0.35), slope (P = 0.73), and stimuli corresponding to TEP threshold (P = 0.7) and maximal TEP amplitude (P = 0.73). These results are for the left SOL TEP, but similar findings were found for all remaining TEPs.

Fig. 6.

Spinal plasticity after a-tsCCS. TEP recruitment curves: recruitment input-output curves of TEPs recorded bilaterally from the TA, MG, SOL, GRC, MH, RF, and VM muscles from all subjects. x-Axis shows multiples of TEP resting threshold. y-Axis shows the TEP sizes as % of the associated maximal TEP size obtained before transspinal stimulation.

For c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS groups, three-way RM ANOVA on the predicted maximal TEP amplitudes recorded from ankle muscles showed a significant effect of polarity [F(5,1,1) = 10.98, P = 0.001], and an interaction between time and polarity [F(5,1,1) = 7.98, P = 0.005], but not for muscle [F(5,1,1) = 0.73, P = 0.59]. In contrast, three-way RM ANOVA on the predicted maximal TEP amplitudes recorded from knee/thigh muscles showed a significant effect of muscle [F(7,1,1) = 2.45, P = 0.02] but not a significant effect of stimulus polarity [F(7,1,1) = 0.08, P = 0.77] with an exception for the right GRC (t = 2.17, P < 0.05), right VM (t = 3.66, P < 0.05), and right RF (t = 0.077, P < 0.05) muscles. An interaction between muscle and time was also found [F(7,1,1) = 1.87, P = 0.033].

Spinal Plasticity After Transspinal Stimulation: Postactivation Depression

The altered multisegmental spinal output described above may be due to changes in spinal inhibition induced by transspinal stimulation. To elucidate this, we recorded TEPs and soleus H reflexes at an interstimulus interval of 5 s and 1 s before and after transspinal stimulation.

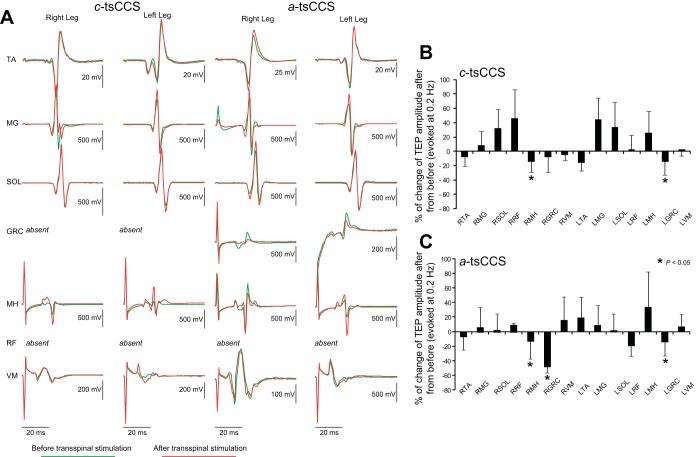

Figure 7A illustrates TEPs from one participant (subject 12) before and after 40 min of c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS elicited at an interstimulus interval of 5 s. It should be noted that the shape of TEPs induced by cathodal stimulation is similar to those evoked by anodal stimulation (see Fig. 2 in Knikou 2013b), but similarities and/or differences in the neurophysiological properties of TEPs evoked by anodal and cathodal stimulation require further investigation. Figure 7, B and C, illustrate the overall percent change in TEP sizes recorded at an interstimulus interval of 5 s after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS from all subjects. TEP sizes from thigh muscles (right MH, right/left GRC) were decreased (P = 0.003) after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS, while no differences were found for the remaining TEPs.

Fig. 7.

Spinal plasticity after 40 min of a-tsCCS and c-tsCCS: TEPs recorded at 0.2 Hz. A: nonrectified waveform averages of TEPs from 1 representative subject before and after 40 min of c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS. TEPs were recorded at an intensity equivalent to 1.2 TEP resting threshold at 0.2 Hz. B and C: overall % change for each TEP recorded at 0.2 Hz after transspinal stimulation from the associated TEP recorded before transspinal stimulation. x-Axis shows the muscle from which TEPs were recorded. Error bars indicate SE.

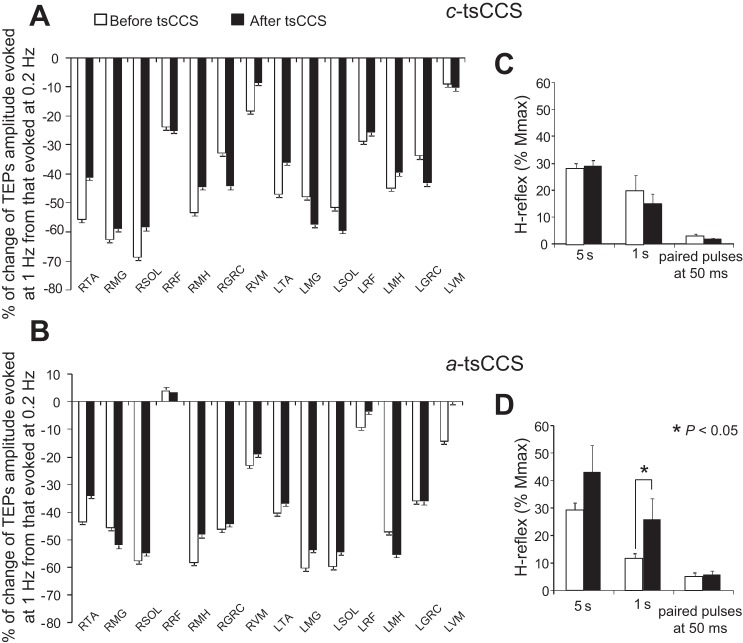

TEP postactivation depression is easily recognized by the overall percent change observed in the TEP amplitude when evoked at 1 s from 5 s before transspinal stimulation (Fig. 8, A and B). The percentage of change in TEP amplitude from all subjects was statistically significant different across muscles [F(12,1) = 8.52, P < 0.001] but not based on time of testing [F(12,1) = 0.52, P = 0.46] or on their interaction [F(12,1) = 0.6, P = 0.82] after c-tsCCS. Similarly, no difference was found for TEP sizes evoked at 1 s before and after a-tsCCS.

Fig. 8.

Spinal plasticity after 40 min of c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS: postactivation depression. A and B: % of change for each TEP evoked at an interstimulus interval of 1 s from the associated TEP recorded at an interstimulus interval of 5 s before and after transspinal stimulation from all subjects. x-Axis shows the muscle from which TEPs were recorded. C and D: amplitude of soleus H reflexes from all subjects before and after c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS at interstimulus intervals of 5 s and 1 s and following paired pulses at an interstimulus interval of 50 ms at a constant stimulation frequency (0.2 Hz). Soleus H reflexes were normalized to the maximal M wave. Error bars indicate SE.

c-tsCCS did not affect the soleus H-reflex size evoked at 5 s (P = 0.63) or 1 s (P = 0.16) or after paired pulses at an interstimulus interval of 50 ms at a constant stimulation frequency of 0.2 Hz (P = 0.16; Fig. 8C). a-tsCCS reduced the amount of soleus H-reflex depression at low frequencies, i.e., at an interstimulus interval of 1 s (P = 0.039; Fig. 8D), but did not affect the H-reflex size at 5 s (P = 0.11). Repeated-measures ANOVA on the normalized H reflexes from all subjects showed a significant effect of interstimulus interval [F(1,1,1) = 15.1, P < 0.001] but not of polarity [F(1,1,1) = 1.4, P = 0.23] or time [F(1,1,1) = 2.7, P = 0.1]. A significant interaction between polarity and time [F(1,1) = 4.88, P = 0.031] was found.

DISCUSSION

Transspinal constant-current long-lasting stimulation induced cortical, corticospinal, and spinal plasticity in healthy human subjects. Our results support our hypothesis that prolonged transcutaneous stimulation over the thoracolumbar enlargement can induce functional neuroplasticity. The neurophysiological changes and mechanisms of neuroplasticity after transspinal stimulation along with limitations of this study are discussed below.

Neurophysiological Changes After Transspinal Stimulation

c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS decreased the afferent-mediated MEP facilitation (Fig. 2, B and D). Furthermore, c-tsCCS increased the subthreshold TMS-mediated TA flexor reflex facilitation but a-tsCCS decreased the subthreshold TMS-mediated TA flexor reflex facilitation (Fig. 3, B and D). These neurophysiological changes most likely reflect plasticity of cortical neuronal circuits. This is supported by the finding that the increased MEP sizes and firing rate of single TA motor units following stimulation of mixed peripheral or sensory nerves at similar time delays (Aimonetti and Nielsen 2001; Deletis et al. 1992; Deuschl et al. 1991; Devanne et al. 2009; Kasai et al. 1992; Khaslavskaia et al. 2002; Mackey et al. 2015; Nielsen et al. 1997; Roy and Gorassini 2008; Tamburin et al. 2001) coincide with absent changes in the cervicomedullary MEPs (Roy and Gorassini 2008), increases in intracortical excitation (Devanne et al. 2009; Di Lazzaro et al. 1999; Roy and Gorassini 2008), and absent changes of soleus H-reflex excitability (Mariorenzi et al. 1991). Furthermore, at the C-T intervals ranging from −80 to −50 ms, cutaneous afferents have ample time to reach the somatosensory cortex and via thalamocortical circuits (Fig. 1A) affect the conditioned MEPs' amplitude at the site of their origin. In addition, the parallel facilitation of flexor reflexes by subthreshold TMS before transspinal stimulation supports further involvement of cortical neuronal circuits, since subthreshold TMS suppresses the descending spinal cord volleys and the muscle responses evoked by a subsequent suprathreshold TMS pulse through corticocortical inhibitory circuits (Chen et al. 1998; Di Lazzaro et al. 1998; Kujirai et al. 1993).

Our findings suggest that transspinal stimulation can change activity in cortical neuronal circuits. Indeed, during spinal cord stimulation the cortical silent period is prolonged and the intracortical inhibition is increased (Schlaier et al. 2007). Moreover, cathodal transspinal direct-current stimulation (tsDCS) decreases intracortical inhibition, while anodal tsDCS decreases the amplitude of somatosensory evoked potentials (Bocci et al. 2015; Cogiamanian et al. 2008). In light of the similar effects of c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS on the afferent-mediated MEP facilitation and their different influences on the subthreshold TMS-mediated effects on the TA flexor reflex (compare Figs. 2 and 3), it is possible that the observed changes are the result of different cortical neuronal circuits on which transspinal stimulation has distinct influences.

While the changes observed on the afferent-mediated TA MEP facilitation and subthreshold TMS-mediated TA flexor reflex facilitation point toward cortical plasticity induced by transspinal stimulation, both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS potentiated corticospinal excitability. The TA MEPs recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold, intermediate, and maximal intensities were substantially increased after stimulation (Fig. 4, B, C, E, and F). The latencies and thresholds of MEPs recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold intensities remained unaltered, suggesting that the same neuronal populations were recruited by TMS before and after tsCCS, and that membrane excitability changes are not a major mechanism contributing to MEP facilitation.

The increasing MEP amplitudes with increasing stimulation intensities (recruitment curve) have been related to the strength of corticospinal projections (Chen et al. 1998) and are affected by the excitability state of cortical neurons, spinal motoneurons, and spinal interneurons (Devanne et al. 1997). However, MEPs recorded at different stimulation intensities can reflect the cortical map reorganization after ischemia and limb amputation (Ridding and Rothwell 1997). Thus, while a distinction between organizational and excitability changes cannot readily be made based on the experimental protocol we utilized, the MEP recruitment curve can provide information on cortical reorganization.

MEP excitability is influenced by single-pulse transspinal conditioning stimuli, is decreased when EPSPs for MEPs and TEPs are summated (Knikou 2014), and is increased at intervals consistent with MEP facilitation by peripheral nerve stimulation via cortical mechanisms (Roy and Gorassini 2008). Based on the summation of EPSPs induced by transspinal and transcranial stimulation, MEPs and TEPs likely share common neuronal pathways. This constitutes a possibility for LTP of synaptic transmission to account for the MEP facilitation we observed (Bennett 2000). While LTP typically results from repetitive stimulus pairs timed with presynaptic potentials to arrive before postsynaptic potentials, non-Hebbian LTP in the thalamus, cerebellar circuits, and spinal lamina I neurons has been reported (Naka et al. 2013; Piochon et al. 2013; Sieber et al. 2013). Increases in local field potentials of the gracile nucleus, changes in excitability of the primary motor cortex, and intracortical inhibition are reported after anodal and cathodal tsDCS in humans (Bocci et al. 2015; Lim and Shin 2011) and animals (Aguilar et al. 2011; Ahmed 2011). These findings along with our current results support the notion that transspinal stimulation increases corticospinal excitability in a non-polarity-dependent manner, opposite to that known for transcranial or transspinal DC stimulation in humans and anesthetized mice (Ahmed 2011; Nitsche and Paulus 2000).

In an effort to delineate whether transspinal stimulation induces spinal plasticity, we assessed changes in the TEP amplitudes recorded at different stimulation intensities (i.e., input-output recruitment curve) and changes in postactivation depression of the soleus H reflex and TEPs. c-tsCCS affected the stimulus/response TEP recruitment curves largely in a non-muscle-specific manner (Fig. 5). In contrast, a-tsCCS did not change the stimulus/response TEP recruitment curves recorded from extensors or flexors (Fig. 6). When TEPs were recorded at 0.2 Hz at similar stimulation intensities before and after 40 min of transspinal stimulation, both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS decreased the TEPs tested in knee flexors of both legs (Fig. 7, B and C). It should be noted that pathological activity of knee flexors contributes to pathological synergistic movements in neurological disorders. These findings suggest that c-tsCCS can simultaneously affect different motoneuron pools, and this may be related to the anatomical topography of spinal motoneurons within the gray matter and local synaptic and nonsynaptic neuroplasticity.

The amplitude of TEPs evoked every 1 s was reduced by as much as 60% from that of TEPs evoked every 5 s, especially in those recorded from the distal ankle muscles. This phenomenon, known as homosynaptic (or postactivation or low frequency) depression (Fig. 1C), is apparent in the soleus H reflex and occurs at the Ia afferent-motoneuron synapse because of reduced transmitter release from the previously activated Ia afferents (Pierrot-Deseilligny and Burke 2012). The presence of postactivation TEP depression in this study is opposite to what we have previously observed on a-tsCCS and transcutaneous magnetic stimulation of the spine in semiprone seated subjects (Einhorn et al. 2013; Knikou 2013a, 2013b), suggesting that body position is key to some of the neurophysiological properties of TEPs. However, postactivation TEP depression cannot readily be used to characterize TEPs as monosynaptic reflexes because α-motoneurons upon transspinal stimulation are depolarized mostly by transsynaptic actions (see Excitation of Neuronal Elements upon tsCCS).

c-tsCCS or a-tsCCS did not affect the postactivation depression of TEPs (Fig. 8, A and B), but a-tsCCS decreased the soleus H-reflex postactivation depression (Fig. 8D). The latter finding is consistent with the reduced soleus H-reflex postactivation depression and the progressive increase of soleus H-reflex excitability after a-tsDCS (Lamy et al. 2012; Winkler et al. 2010). In our study, H-reflex excitability represented by the H reflexes recorded at 0.2 Hz did not show significant changes after transspinal stimulation, a finding also reported after a-tsDCS or c-tsDCS (Winkler et al. 2010). The decreased soleus H-reflex postactivation depression may be the result of membrane potential changes of primary afferent fibers (Eccles et al. 1962), facilitating transmitter release at the Ia fiber-motoneuron synapse.

To summarize, both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS decreased afferent-mediated MEP facilitation, c-tsCCS increased TMS-mediated TA flexor reflex facilitation, and a-tsCCS decreased TMS-mediated TA flexor reflex facilitation. Furthermore, both c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS increased MEPs recorded at 1.2 MEP resting threshold, intermediate, and maximal intensities. While a-tsCCS did not alter the TEP recruitment curve, c-tsCCS changed their recruitment in a nonspecific pattern, but both a-tsCCS and c-tsCCS decreased the TEPs of knee flexors when recorded at a constant intensity. Finally, postactivation depression of TEPs remained unaltered but was decreased for the soleus H reflex after a-tsCCS and remained unaltered after c-tsCCS.

It is thus apparent that c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS delivered at identical levels of stimulation intensities can induce similar, opposite, or different effects. The differences in the effects of a-tsCCS and c-tsCCS on neuronal excitability suggest that these two types of stimulation act via different mechanisms. While c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS increased corticospinal excitability, subthreshold TMS-mediated flexor reflex facilitation, TEP amplitude, and postactivation depression of the soleus H reflex were affected differently based on the polarity of stimulation. While these differences may be related to interindividual variability of GABAA-GABAB-mediated inhibition and to a variety of neurochemical substances involved in spinal cord stimulation (Linderoth et al. 1992), a-tsCCS and c-tsCCS may have affected differently spinal inhibitory/excitatory interneurons. This is reflected by the opposing effects of DC stimulation on reciprocal inhibition directed from flexors to extensors and from extensors to flexors (Lackmy-Vallée et al. 2014). Additionally, current is known to induce concomitantly depolarization and hyperpolarization of neurons, dendrites, and axons based on their anatomical topography with respect to the stimulating electrode (Delgado-Lezama et al. 1999), thereby affecting neuroplasticity-mediated calcium and sodium channels (Nitsche et al. 2003) differently. Thus, while neurophysiological excitability changes by cathodal DC stimulation are related to membrane depolarization and by anodal DC stimulation to membrane hyperpolarization (Nitsche et al. 2003), it is possible that tsCCS induces both depolarization and hyperpolarization regardless of polarity. These arguments are supported by the differential effect of c-tsCCS on the motor output of knee and ankle muscles (Fig. 5).

Plasticity After Transspinal Stimulation

Long-lasting tsCCS induced cortical, corticospinal, and spinal plasticity in healthy human subjects. The neurophysiological changes described above likely involved changes in the synaptic efficacy between cortical interneurons and descending motor axons (Fig. 1A), descending motor axons and spinal motoneurons (Fig. 1B), and Ia afferents and motoneurons (Fig. 1C). Changes in the intrinsic properties of spinal motoneurons and resting membrane potentials of dendrites, axons, and afferent fibers (Armano et al. 2000; Camp 2012; Daoudal and Debanne 2003; Heckman et al. 2008) constitute plausible sites for nonsynaptic plasticity after long-lasting transspinal stimulation. Polarizing DC surface currents have been shown to produce parallel changes in spontaneous neuron activity, dendritic potentials, and membrane potentials of pyramidal tract cells (Creutzfeldt et al. 1962; Purpura and McMurtry 1965). Positive (anodal) currents increase and negative (cathodal) currents decrease these potentials (Creutzfeldt et al. 1962; Purpura and McMurtry 1965). While in this study we did not use direct current, constant-current stimulation at low frequencies can increase the probability that an EPSP will elicit an action potential, a nonsynaptic plasticity mechanism described as EPSP-spike plasticity (Daoudal and Debanne 2003). Thus it is highly likely that transspinal stimulation induced synaptic and nonsynaptic plasticity coherently, sharing common induction and expression mechanisms (Campanac and Debanne 2007).

Excitation of Neuronal Elements upon tsCCS

The neuronal elements that were excited upon transcutaneous stimulation of the spinal cord need to be considered. Stimulation was delivered for all subjects at the T10–L2 vertebral levels to counteract differences in shape and thus neurophysiological properties based on stimulation level (Roy et al. 2012). The nonuniform shape of TEPs across muscles (Fig. 7A) supports the concept of excitation of different types of fibers. Several studies have proposed that TEPs are generated by excitation of dorsal column fibers, orthodromic excitation of motor axons, and antidromic excitation of muscle afferents leading to strong facilitation of motoneurons and altered transmission in reflex pathways to motoneurons (Coburn 1985; Hunter and Ashby 1994; Maertens de Noordhout et al. 1988).

Stimulation through surface electrodes placed similarly to those in the present study induces a current flow perpendicular to the spine with the concentration of the current located near the transspinal electrode (Minassian et al. 2007). Computational models of epidural or transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation over the lumbosacral cord demonstrated that Ia afferents in dorsal root fibers have significantly lower excitation thresholds compared with ventral root fibers and dorsal column fibers (Rattay et al. 2000), with the latter requiring triple the stimulation intensity (Danner et al. 2011). Furthermore, dorsal column fibers are insusceptible to excitation within the clinical range of 10 V (Rattay et al. 2000). Therefore, dorsal column fibers along with their collaterals could have been excited only when stimulation was delivered at high intensities, although this is unlikely (Danner et al. 2014). Based on differences between indirect (spinal stimulation) and direct (F wave) latencies, scan measurements of the distance between the dura and intervertebral foramina, and simulation studies, transspinal stimulation excites the nerve roots near their exit from the spinal column, near the emergence of the axons from the anterior horn cells, or close to the entry point of the dorsal root fibers (Danner et al. 2011, 2014; Ladenbauer et al. 2010; Mills and Murray 1986; Struijk et al. 1993). Although the exact excitation site cannot be determined from the present experiments, impulses following transcutaneous stimulation of the spinal cord traveled caudally and rostrally, affecting both descending motor inputs and ascending afferent inputs through synaptic and nonsynaptic actions changing motor cortex output at its origin site.

Limitations

Limitations of this study are that the number of tested subjects was small and the time course of excitability changes was not examined. However, the main scope of this exploratory research work was to assess prospective excitability changes of the CNS, allowing appropriate power analysis for future studies. Larger-scale neurophysiological research studies are needed to comprehensively characterize neuroplasticity after long-lasting transspinal stimulation in humans. In this study, no sham stimulation was applied. In our opinion, it is unlikely that the observed neurophysiological changes were due to a placebo effect, since the subjects were blind to the stimulation polarity and the effects of stimulation, while any change in muscle activity would have been identified by the surface EMG electrodes. In future studies, assessment of somatosensory and cervicomedullary evoked potentials, intracortical inhibition, intracortical facilitation, interhemispheric inhibition, and pre- and postsynaptic inhibition exerted on spinal motoneurons (Knikou 2008; Rossini et al. 2015) will contribute to a better understanding of the physiological changes underlying this intervention.

Conclusions

This is the first report on neurophysiological excitability changes after 40 min of cathodal and anodal transspinal stimulation in healthy human subjects. Our findings demonstrate that c-tsCCS and a-tsCCS can induce changes in intracortical and corticospinal excitability and presynaptic inhibition of Ia afferents. We suggest that brain plasticity may be achieved through transspinal stimulation, an intervention that is ideal for people with neurological disorders due to brain or spinal lesions.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the New York State Department of Health, Spinal Cord Injury Research Board, Wadsworth Center (Contract No. C030173 to M. Knikou).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.K. conception and design of research; M.K., L.D., D.S., and M.M.I. performed experiments; M.K., L.D., D.S., and M.M.I. analyzed data; M.K. interpreted results of experiments; M.K. prepared figures; M.K. drafted manuscript; M.K. edited and revised manuscript; M.K., L.D., D.S., and M.M.I. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aguilar J, Pulecchi F, Dilena R, Oliviero A, Priori A, Foffani G. Spinal direct current stimulation modulates the activity of gracile nucleus and primary somatosensory cortex in anaesthetized rats. J Physiol 589: 4981–4996, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z. Trans-spinal direct current stimulation modulates motor cortex-induced muscle contraction in mice. J Appl Physiol 110: 1414–1424, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimonetti JM, Nielsen JB. Changes in intracortical excitability induced by stimulation of wrist afferents in man. J Physiol 534: 891–902, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armano S, Rossi P, Taglietti V, D'Angelo E. Long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability at the mossy fiber-granule cell synapse of rat cerebellum. J Neurosci 20: 5208–5216, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SN, Curio G, Lemon RN. EEG oscillations at 600 Hz are macroscopic markers for cortical spike bursts. J Physiol 550: 529–34, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawa P, Lemon RN. Recruitment of motor units in response to transcranial magnetic stimulation in man. J Physiol 471: 445–464, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MR. The concept of long term potentiation of transmission at synapses. Prog Neurobiol 60: 109–137, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocci T, Barloscio D, Vergari M, Di Rollo A, Rossi S, Priori A, Sartucci F. Spinal direct current stimulation modulates short intracortical inhibition. Neuromodulation (April 16, 2015). doi: 10.1111/ner.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkworth RS, Türker KS. A method for quantifying reflex responses from intra-muscular and surface electromyogram. J Neurosci Methods 122: 179–193, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Martin JH. Motor cortex bilateral motor representation depends on subcortical and interhemispheric interactions. J Neurosci 29: 6196–206, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp AJ. Intrinsic neuronal excitability: a role in homeostasis and disease. Front Neurol 3: 50, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanac E, Debanne D. Plasticity of neuronal excitability: Hebbian rules beyond the synapse. Arch Ital Biol 145: 277–287, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Berrol LJ, Brus-Ramer M, Martin JH. Chronic electrical stimulation of the intact corticospinal system after unilateral injury restores skilled locomotor control and promotes spinal axon outgrowth. J Neurosci 30: 10918–10926, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff C, Celnik P, Wassermann EM, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology 48: 1398–1403, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Tam A, Bütefisch C, Corwell B, Ziemann U, Rothwell JC, Cohen LG. Intracortical inhibition and facilitation in different representations of the human motor cortex. J Neurophysiol 80: 2870–2881, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn B. A theoretical study of epidural electrical stimulation of the spinal cord—Part II: Effects on long myelinated fibers. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 32: 978–986, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogiamanian F, Vergari M, Pulecchi F, Marceglia S, Priori A. Effect of spinal transcutaneous direct current stimulation on somatosensory evoked potentials in humans. Clin Neurophysiol 119: 2636–2640, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LG, Ziemann U, Chen R, Classen J, Hallett M, Gerloff C, Butefisch C. Studies of neuroplasticity with transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Clin Neurophysiol 15: 305–324, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt OD, Fromm GH, Kapp H. Influence of transcortical d-c currents on cortical neuronal activity. Exp Neurol 5: 436–452, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y, Poo MM. Spike timing-dependent plasticity: from synapse to perception. Physiol Rev 86: 1033–1048, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner SM, Hofstoetter US, Krenn M, Mayr W, Rattay F, Minassian K. Potential distribution and nerve fiber responses in transcutaneous lumbosacral spinal cord stimulation. IFMBE Proc 44: 203–208, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Danner SM, Hofstoetter US, Ladenbauer J, Rattay F, Minassian K. Can the human lumbar posterior columns be stimulated by transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation? A modeling study. Artif Organs 35: 257–262, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoudal G, Debanne D. Long-term plasticity of intrinsic excitability: learning rules and mechanisms. Learn Mem 10: 456–465, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deletis V, Schild JH, Berić A, Dimitrijević MR. Facilitation of motor evoked potentials by somatosensory afferent stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 85: 302–310, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Lezama R, Perrier JF, Hounsgaard J. Local facilitation of plateau potentials in dendrites of turtle motoneurones by synaptic activation of metabotropic receptors. J Physiol 515: 203–207, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G, Michels R, Berardelli A, Schenck E, Inghilleri M, Lücking CH. Effects of electric and magnetic transcranial stimulation on long latency reflexes. Exp Brain Res 83: 403–410, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanne H, Degardin A, Tyvaert L, Bocquillon P, Houdayer E, Manceaux A, Derambure P, Cassim F. Afferent-induced facilitation of primary motor cortex excitability in the region controlling hand muscles in humans. Eur J Neurosci 30: 439–448, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanne H, Lavoie BA, Capaday C. Input-output properties and gain changes in the human corticospinal pathway. Exp Brain Res 114: 329–338, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Restuccia D, Oliviero A, Profice P, Ferrara L, Insola A, Mazzone P, Tonali P, Rothwell JC. Magnetic transcranial stimulation at intensities below active motor threshold activates intracortical inhibitory circuits. Exp Brain Res 119: 265–268, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Rothwell JC, Oliviero A, Profice P, Insola A, Mazzone P, Tonali P. Intracortical origin of the short latency facilitation produced by pairs of threshold magnetic stimuli applied to human motor cortex. Exp Brain Res 129: 494–499, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Kostyuk PG, Schmidt RF. The effect of electric polarization of the spinal cord on central afferent fibres and on their excitatory synaptic action. J Physiol 162: 138–150, 1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgley SA, Eyre JA, Lemon RN, Miller S. Comparison of activation of corticospinal neurons and spinal motor neurons by magnetic and electrical transcranial stimulation in the lumbosacral cord of the anaesthetized monkey. Brain 120: 839–853, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn J, Li A, Hazan R, Knikou M. Cervicothoracic multisegmental transpinal evoked potentials in humans. PLoS One 8: e76940, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellaway PH. Cumulative sum technique and its application to the analysis of peristimulus time histograms. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 45: 302–304, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna-Boutros B, Sangari S, Giboin LS, El Mendili MM, Lackmy-Vallée A, Marchand-Pauvert V, Knikou M. Corticospinal and reciprocal inhibition actions on human soleus motoneuron activity during standing and walking. Physiol Rep 3: e12276, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema S, Gerasimenko Y, Hodes J, Burdick J, Angeli C, Chen Y, Ferreira C, Willhite A, Rejc E, Grossman RG, Edgerton VR. Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study. Lancet 377: 1938–1947, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Johnson M, Mottram C, Schuster J. Persistent inward currents in spinal motoneurons and their influence on human motoneuron firing patterns. Neuroscientist 14: 264–275, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JI, Willis WD. Mobilization of transmitter by hyperpolarization. Nature 193: 173–174, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JP, Ashby P. Segmental effects of epidural spinal cord stimulation in humans. J Physiol 474: 407–419, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilge B, Minassian K, Rattay F, Pinter MM, Gerstenbrand F, Binder H, Dimitrijevic MR. Initiating extension of the lower limbs in subjects with complete spinal cord injury by epidural lumbar cord stimulation. Exp Brain Res 154: 308–326, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph C. Plasticity. Handb Clin Neurol 116: 525–534, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai T, Hayes KC, Wolfe DL, Allatt RD. Afferent conditioning of motor evoked potentials following transcranial magnetic stimulation of motor cortex in normal subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 85: 95–101, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG. Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Khaslavskaia S, Ladouceur M, Sinkjaer T. Increase in tibialis anterior motor cortex excitability following repetitive electrical stimulation of the common peroneal nerve. Exp Brain Res 145: 309–315, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M. The H-reflex as a probe: pathways and pitfalls. J Neurosci Methods 171: 1–12, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M. Neurophysiological characteristics of human leg muscle action potentials evoked by transcutaneous magnetic stimulation of the spine. Bioelectromagnetics 34: 200–210, 2013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M. Neurophysiological characterization of transpinal evoked potentials in human leg muscles. Bioelectromagnetics 34: 630–640, 2013b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M. Transpinal and transcortical stimulation alter corticospinal excitability and increase spinal output. PloS One 9: e102313, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M, Dixon L, Santora D, Ibrahim MM. Targeted human cortical and spinal neuroplasticity by transpinal stimulation (Abstract). Soc Neurosci Abstr 2015: 2015-S-2039-SfN, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M, Hajela N, Mummidisetty CK. Corticospinal excitability during walking in humans with absent and partial body weight support. Clin Neurophysiol 124: 2431–2438, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Ferbert A, Wroe S, Asselman P, Marsden CD. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol 471: 501–519, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackmy-Vallée A, Klomjai W, Bussel B, Katz R, Roche N. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the motor cortex induces opposite modulation of reciprocal inhibition in wrist extensor and flexor. J Neurophysiol 112: 1505–1515, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenbauer J, Minassian K, Hofstoetter US, Dimitrijevic MR, Rattay F. Stimulation of the human lumbar spinal cord with implanted and surface electrodes: a computer simulation study. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 18: 637–645, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy JC, Ho C, Badel A, Arrigo RT, Boakye M. Modulation of soleus H reflex by spinal DC stimulation in humans. J Neurophysiol 108: 906–914, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CY, Shin HI. Noninvasive DC stimulation on neck changes MEP. Neuroreport 22: 819–823, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linderoth B, Gazelius B, Franck J, Brodin E. Dorsal column stimulation induces release of serotonin and substance P in the cat dorsal horn. Neurosurgery 31: 289–296, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey AS, Uttaro D, McDonough MP, Krivis LI, Knikou M. Convergence of flexor reflex and corticospinal inputs on tibialis anterior network in humans. Clin Neurophysiol pii: S1388–S2547(15)00640-9, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens de Noordhout A, Rothwell JC, Thompson PD, Day BL, Marsden CD. Percutaneous electrical stimulation of lumbosacral roots in man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 51: 174–181, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariorenzi R, Zarola F, Caramia MD, Paradiso C, Rossini PM. Non-invasive evaluation of central motor tract excitability changes following peripheral nerve stimulation in healthy humans. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 81: 90–101, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama Y, Shimoji K, Shimizy H, Kuribayashi H, Fujioka H. Human spinal cord potentials evoked by different sources of stimulation and conduction velocities along the cord. J Neurophysiol 48: 1098–1107, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KR, Murray NM. Electrical stimulation over the human vertebral column: which neural elements are excited? Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 63: 582–589, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian K, Hofstoetter US, Danner SM, Mayr W, Bruce JA, McKay WB, Tansey KE. Spinal rhythm generation by step-induced feedback and transcutaneous posterior root stimulation in complete spinal cord-injured individuals. Neurorehab Neural Repair pii: 1545968315591706, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian K, Persy I, Rattay F, Pinter MM, Kern H, Dimitrijevic MR. Human lumbar cord circuitries can be activated by extrinsic tonic input to generate locomotor-like activity. Hum Mov Sci 26: 275–295, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka A, Gruber-Schoffnegger D, Sandkühler J. Non-Hebbian plasticity at C-fiber synapses in rat spinal cord lamina I neurons. Pain 154: 1333–1342, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J, Petersen N, Fedirchuk B. Evidence suggesting a transcortical pathway from cutaneous foot afferents to tibialis anterior motoneurones in man. J Physiol 501: 473–484, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Fricke K, Henschke U, Schlitterlau A, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Henning S, Tergau F, Paulus W. Pharmacological modulation of cortical excitability shifts induced by transcranial direct current stimulation in humans. J Physiol 553: 293–301, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol 527: 633–639, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Sole J, Wassermann EM, Hallett M. Responses to rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain 117: 847–858, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Burke D. Spinal and Corticospinal Mechanisms of Movement. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Piochon C, Kruskal P, Maclean J, Hansel C. Non-Hebbian spike-timing-dependent plasticity in cerebellar circuits. Front Neural Circuits 6: 124, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purpura DP, McMurtry JG. Intracellular activities and evoked potential changes during polarization of motor cortex. J Neurophysiol 28: 166–185, 1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattay F, Minassian K, Dimitrijevic MR. Epidural electrical stimulation of posterior structures of the human lumbosacral cord. 2. Quantitative analysis by computer modeling. Spinal Cord 38: 473–489, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridding MC, Rothwell JC. Stimulus/response curves as a method of measuring motor cortical excitability in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 105: 340–344, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioult-Pedotti MS, Friedman D, Donoghue JP. Learning-induced LTP in neocortex. Science 290: 533–536, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini PM, Burke D, Chen R, Cohen LG, Daskalakis Z, Di Iorio R, Di Lazzaro V, Ferreri F, Fitzgerald PB, George MS, Hallett M, Lefaucheur JP, Langguth B, Matsumoto H, Miniussi C, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, Paulus W, Rossi S, Rothwell JC Siebner HR, Ugawa Y, Walsh V, Ziemann U. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord, roots and peripheral nerves: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical and research application. An updated report from an I.F.C.N. Committee. Clin Neurophysiol 126: 1071–1107, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy FD, Gibson G, Stein RB. Effect of percutaneous stimulation at different spinal levels on the activation of sensory and motor roots. Exp Brain Res 223: 281–289, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy FD, Gorassini MA. Peripheral sensory activation of cortical circuits in the leg motor cortex of man. J Physiol 586: 4091–4105, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaier JR, Eichhammer P, Langguth B, Doenitz C, Binder H, Hajak G, Brawanski A. Effects of spinal cord stimulation on cortical excitability in patients with chronic neuropathic pain: a pilot study. Eur J Pain 11: 863–868, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe AN, Jackson A. Upper-limb muscle responses to epidural, subdural and intraspinal stimulation of the cervical spinal cord. J Neural Eng 11: 016005, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber AR, Min R, Nevian T. Non-Hebbian long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses in the thalamus. J Neurosci 33: 15675–15685, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Kunesch E, Benecke R, Cohen LG, Classen J. Mechanisms of enhancement of human motor cortex excitability induced by interventional paired associative stimulation. J Physiol 543: 699–708, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Kunesch E, Cohen LG, Benecke R, Classen J. Induction of plasticity in the human motor cortex by paired associative stimulation. Brain 123: 572–584, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struijk JJ, Holsheimer J, Boom HB. Excitation of dorsal root fibers in spinal cord stimulation: a theoretical study. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 40: 632–639, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburin S, Manganotti P, Zanette G, Fiaschi A. Cutaneomotor integration in human hand motor areas: somatotopic effect and interaction of afferents. Exp Brain Res 141: 232–241, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thickbroom GW, Byrnes ML, Edwards DJ, Mastaglia FL. Repetitive paired-pulse TMS at I-wave periodicity markedly increases corticospinal excitability: a new technique for modulating synaptic plasticity. Clin Neurophysiol 117: 61–66, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler T, Hering P, Straube A. Spinal DC stimulation in humans modulates post-activation depression of the H-reflex depending on current polarity. Clin Neurophysiol 121: 957–961, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters A, Sandbrink F, Schlottmann A, Kunesch E, Stefan K, Cohen LG, Benecke R, Classen J. A temporally asymmetric Hebbian rule governing plasticity in the human motor cortex. J Neurophysiol 89: 2339–2345, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]