Abstract

Intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) is platelet aggregation-inducing molecule and is involved in activation of aggregation associated molecules. This study was carried out to understand the Ca2+-antagonistic effect of ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro), an oleanane-type saponin in Panax ginseng. G-Ro, without affecting leakage of lactate dehydrogenase, dose-dependently inhibited thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, and the half maximal inhibitory concentration was approximately 155 μM. G-Ro inhibited strongly thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i, which was strongly increased by A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS compared to G-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS. G-Ro increased the level of cAMP and subsequently elevated the phosphorylation of inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor I (IP3RI) (Ser1756) to inhibit [Ca2+]i mobilization in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. Phosphorylation of IP3RI (Ser1756) by G-Ro was decreased by PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS. In addition, G-Ro inhibited thrombin-induced phosphorylation of ERK 2 (42 kDa), indicating inhibition of Ca2+ influx across plasma membrane. We demonstrate that G-Ro upregulates cAMP-dependent IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation and downregulates phosphorylation of ERK 2 (42 kDa) to decrease thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i, which contributes to inhibition of ATP and serotonin release, and p-selectin expression. These results indicate that G-Ro in Panax ginseng is a beneficial novel Ca2+-antagonistic compound and may prevent platelet aggregation-mediated thrombotic disease.

1. Introduction

The full platelet aggregation by physiological agonists (i.e., thrombin, ADP, and collagen) is absolutely essential for the formation of a hemostatic plug when normal blood vessels are injured. This physiological event is underlied by an elevation of cytosolic free Ca2+ level ([Ca2+]i) and can also cause circulatory disorders, such as thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarction [1–3]. Accordingly, inhibiting [Ca2+]i-elevation by platelet agonists is a promising approach for the prevention of thrombosis. Elevation of [Ca2+]i by agonists is dependent on the mobilization from intracellular Ca2+ stores (endoplasmic reticulum or dense tubular system) and the influx of extracellular Ca2+ across plasma membrane (PM) [1–3]. It is known that thrombin, a platelet agonist, stimulates platelet aggregation by binding to the Gq-coupled proteinase-activated receptor, which is involved in activating phospholipase C-β (PLC-β). Activated PLC-β hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DG) [4–7]. Moreover, IP3 mobilizes cytosol free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) from dense tubular system (DTS) by binding to IP3 receptor type I (IP3RI). The increased [Ca2+]i activates both the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of myosin light chain (20 kDa) and the DG-dependent phosphorylation of pleckstrin (47 kDa) to induce granule secretion (i.e., dense body and α-granule) and platelet aggregation [8, 9]. The Ca2+-antagonistic effects of cAMP and cGMP are mediated via cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA and PKG), which phosphorylates substrate protein, IP3RI. The action of IP3RI is inhibited by its phosphorylation, and IP3RI phosphorylation is involved in inhibition of [Ca2+]i mobilization [10–12]. Therefore, phosphorylating IP3RI is very useful for evaluating the Ca2+-antagonistic effect of substances or compounds. With regard to the influx of extracellular Ca2+ across PM, it is well known that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI3K and PI4K) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) are involved in the entry of extracellular Ca2+ across PM by activating the Ca2+-permeable channel protein and human transient receptor potential channel (hTrp1) coupling with IP3R type II (IP3RII) [13–18].

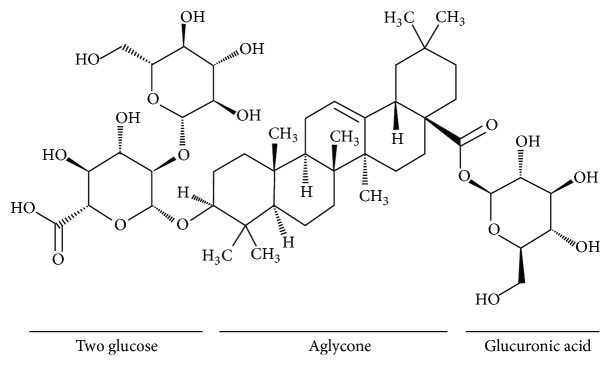

Ginseng, the root of Panax ginseng Meyer, has been used frequently in traditional oriental medicine and is known to have various pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammatory action, antioxidation, antitumor, antidiabetes, and antihepatotoxicity [21, 22]. In recent, it is reported that Korean red ginseng has an effect on cardiovascular disease, which is characterized with regard to reduction of blood pressure and arterial stiffness by inhibition of Rho kinase [23], anticoagulation by prolonged prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin time [24], endothelium relaxation by nitric oxide-cGMP pathway [25], and inhibition of hypercholesterolemia-induced platelet aggregation [26]. In our previous report, we demonstrated that total saponin from Korean red ginseng (TSKRG) is a beneficial traditional oriental medicine in platelet-mediated thrombotic disease via suppression of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and thromboxane A2 synthase (TXAS) to inhibit production of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) [27]. It is reported that ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro, Figure 1) has no inhibitory effect on collagen-elevated [Ca2+]i [28]. However, in this study, we showed that G-Ro attenuates thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i via cAMP-dependent IP3RI phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of ERK in human platelets. This study provides novel information for antiplatelet effects of G-Ro in ginseng.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of ginsenoside Ro. Ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro), an oleanane-type saponin, is contained in Panax ginseng Meyer [19, 20] and is composed of oleanolic acid as aglycone and two glucose and one glucuronic acid as sugar component [19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ginsenoside Ro (G-Ro, Figure 1) was obtained from Ambo Institute (Daejeon, Korea). Thrombin was purchased from Chrono-Log Corporation (Havertown, PA, USA). ATP assay kit was purchased from Biomedical Research Service Center (Buffalo, NY, USA). Serotonin ELISA kit was purchased from Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Corporation (Nordhorn, Germany). A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, G-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS, and 2-acetoxymethyl (Fura 2-AM) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay kit, cAMP enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit, and cGMP enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Anti-IP3-receptor type I, antiphosphor-IP3-receptor type I (Ser1756), anti-ERK (1/2), antiphosphor-ERK (1/2), anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (HRP), and lysis buffer were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-β-actin was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse monoclonal to CD62P (p-selectin) antibody was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane was from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence solution (ECL) was from GE Healthcare (Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.2. Preparation of Washed Human Platelets

Human platelet-rich plasma (PRP) anticoagulated with acid-citrate-dextrose solution (0.8% citric acid, 2.2% sodium citrate, and 2.45% glucose) was obtained from Korean Red Cross Blood Center (Changwon, Korea). PRP was centrifuged for 10 min at 125 g to remove a few red blood cells and white blood cells and was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,300 g to obtain the platelet pellets. The platelets were washed twice with washing buffer (138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.36 mM NaH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, and 1 mM Na2EDTA, pH 6.5). The washed platelets were then resuspended in suspension buffer (138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.36 mM NaH2PO4, 0.49 mM MgCl2, 5.5 mM glucose, and 0.25% gelatin, pH 6.9) to a final concentration of 5 × 108/mL. All of the above procedures were carried out at 25°C to avoid platelet aggregation from any effect of low temperature. The Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy Public Institutional Review Board (Seoul, Korea) approved these experiments (PIRB12-072).

2.3. Measurement of Platelet Aggregation

Human washed platelets (108/mL) were preincubated for 3 min at 37°C in the presence of 2 mM exogenous CaCl2 with or without substances and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) for 5 min. Aggregation was monitored using an aggregometer (Chrono-Log, Corporation) at a constant stirring speed of 1,000 rpm. Each aggregation rate was calculated as an increase in light transmission. The suspension buffer was used as the reference (transmission 0). G-Ro was dissolved in platelet suspension buffer (pH 6.9).

2.4. Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity Assay

Human platelet cytotoxicity was determined by the leakage of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from cytosol. Human washed platelets (108/mL) were incubated for 5 min at 37°C with various concentrations of G-Ro and then centrifuged at room temperature for 2 min at 12,000 g. The supernatant was measured by LDH assay kit (Cayman Chemical) at an optical density of 490 nm. LDH leakage is expressed as the percentage of the total enzyme activity in platelets completely lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100.

2.5. Determination of Cytosolic Free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i)

PRP was incubated with 5 μM Fura 2-AM at 37°C for 60 min. Because Fura 2-AM is light sensitive, the tube containing the PRP was covered with aluminum foil during loading. The Fura 2-loaded washed platelets were prepared using the procedure described above and 108 platelets/mL were preincubated for 3 min at 37°C with or without G-Ro in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) for 5 min for evaluation of [Ca2+]i. Fura 2 fluorescence was measured with a spectrofluorometer (SFM 25, BioTeck Instrument, Italy) with an excitation wavelength that was changed every 0.5 sec from 340 to 380 nm; the emission wavelength was set at 510 nm. The [Ca2+]i values were calculated using the method of Grynkiewicz [29].

2.6. Measurement of cAMP and cGMP

Washed human platelets (108/mL) were preincubated for 3 min at 37°C with or without various concentrations of G-Ro in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) for 5 min for platelet aggregation. The aggregation was terminated by the addition of 80% ice-cold ethanol. cAMP and cGMP were measured with Synergy HT Multi-Model Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.7. Western Blot for Analysis of IP3RI and ERK Phosphorylation

Washed platelets (108/mL) were preincubated with or without G-Ro in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 for 3 min and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) for 5 min at 37°C. The reactions were terminated by adding an equal volume (250 μL) of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM ATPase, alkaline and acid phosphatase, protein phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitor Na3VO4, 1 μg/mL serine and cysteine protease inhibitor leupeptin, and 1 mM serine protease and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.5). Platelet lysates containing the same protein (15 μg) were used for analysis. Protein concentrations were measured by using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, USA). The effects of G-Ro on IP3RI phosphorylations were analyzed by western blotting. A 6–8% SDS-PAGE (1.5 mm gel) was used for electrophoresis and a PVDF membrane was used for protein transfer from the gel. The dilutions for anti-IP3RI, antiphosphor-IP3RI (Ser1756), anti-ERK (1/2), antiphosphor-ERK (1/2), and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP were 1 : 1000, 1 : 1000, 1 : 1000, 1 : 1000, and 1 : 10000, respectively. The membranes were visualized using ECL. Blots were analyzed by using the Quantity One, Version 4.5 (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.8. Determination of ATP and Serotonin Release

Washed platelets (108/mL) were preincubated for 3 min at 37°C with or without G-Ro and other reagents in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL). The reaction was terminated and centrifuged with 200 g at 4°C for 10 min, and supernatants were used for the assay of ATP and serotonin release. ATP release was measured in a luminometer (BioTek Instruments) using an ATP assay kit. Serotonin release was measured with a Synergy HT Multi-Model Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) using serotonin ELISA kit.

2.9. Determination of p-Selectin Release

Washed human platelets (108/mL) were preincubated for 3 min at 37°C with or without substances in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL). The platelets were reconstituted by ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) 250 μL and cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-human CD62P (10 μL) in PBS (pH 7.4), containing 0.09% sodium azide and 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 60 min at 4°C in the dark room. Next, platelets were washed three times by ice-cold PBS and resuspended by 0.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Alexa Fluor 488 anti-human CD62P binding to platelets was determined using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using CellQuest software.

2.10. Statistical Analyses

The experimental results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation accompanied by the number of observations. Data were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). If this analysis indicated significant differences among the group means, then each group was compared by the Newman-Keuls method. Statistical analysis was performed according to the SPSS 21.0.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of G-Ro on Thrombin-Induced Human Platelet Aggregation

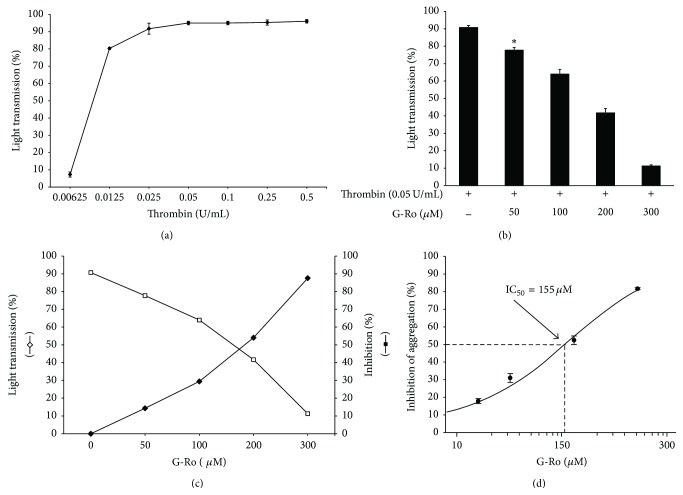

The concentration of thrombin-induced maximal human platelet aggregation was approximately 0.05 U/mL (Figure 2(a)). Therefore, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) was used as the human platelet agonist in this study. When washed human platelets (108/mL) were activated with thrombin, the aggregation rate was increased up to 90.7 ± 1.2%. However, various concentrations of G-Ro (50, 100, 200, and 300 μM) dose-dependently reduced thrombin-stimulated platelet aggregation (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)), and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was approximately 155 μM (Figure 2(d)).

Figure 2.

Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation. (a) The concentration threshold of thrombin on human platelet aggregation. (b) Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation. (c) The inhibitory effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation. (d) The IC50 value of G-Ro in thrombin-stimulated human platelet aggregation. Measurement of platelet aggregation was carried out as described in “Section 2.” The rate of inhibition by G-Ro was recorded as the percentage of the thrombin-induced aggregation rate. The IC50 value of G-Ro was calculated according to the 4-parameter log fit method. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets.

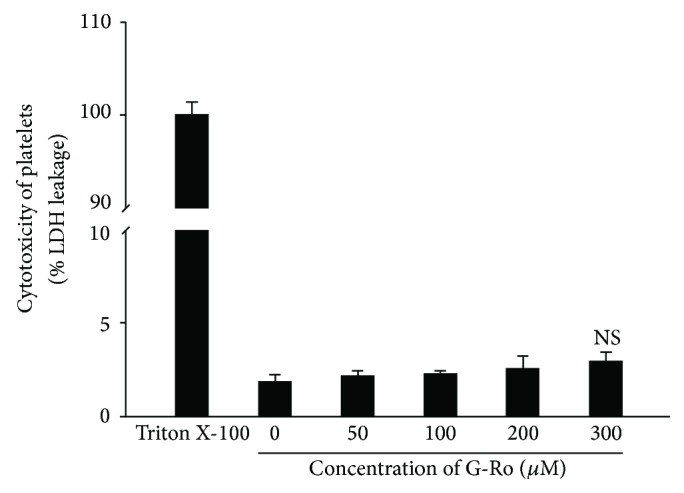

3.2. Effects of Cytotoxicity of G-Ro to Human Platelets

Cytotoxicity of drugs is evaluated by cytosolic LDH leakage, which is different from platelet aggregation or granule secretion by platelet agonists [30–32]. Therefore, we investigate the effect of G-Ro on cytotoxicity to human platelets. When human platelets (108/mL) were treated by membrane detergent Triton X-100 as a positive control, LDH was potently released (Figure 3). However, G-Ro (50 to 300 μM) that inhibited thrombin-induced platelet aggregation did not release LDH as compared to that by Triton X-100. LDH leakage by various concentrations of G-Ro (50, 100, 200, and 300 μM) was 2.1% (at 50 μM of G-Ro), 2.2% (at 100 μM of G-Ro), 2.5% (at 200 μM of G-Ro), and 2.9% (at 300 μM of G-Ro), respectively, which were not significantly different from that (1.8%) by resting platelets (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of G-Ro on cytotoxicity. Measurement of cytotoxicity was carried out as described in “Section 2.” For a positive control, 0.1% Triton X-100 was used to treat platelets. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). NS, not significant versus without G-Ro, control.

3.3. Effects of G-Ro on Elevation of Cytosolic Free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i)

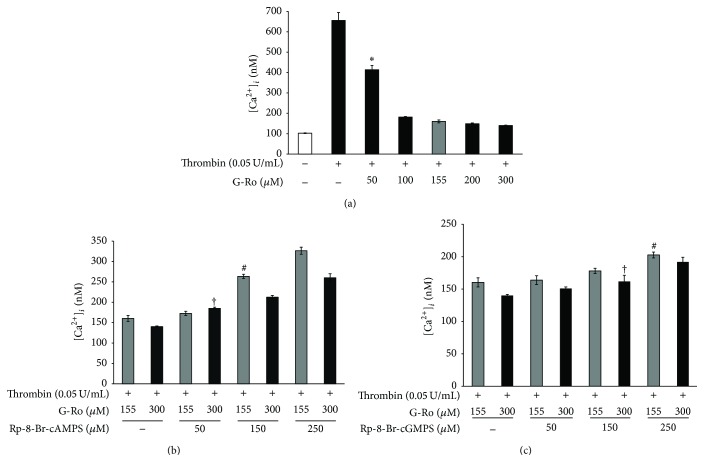

Because [Ca2+]i is essential for platelet activation by agonists, we investigated the effect of G-Ro on Ca2+-antagonistic activity. As shown in Figure 4(a), thrombin increased [Ca2+]i level from 102.4 ± 0.5 nM, the basal level, to 655.7 ± 38.7 nM (Figure 4(a)). However, G-Ro dose-dependently (50 to 300 μM) decreased thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i (Figure 4(a)). If G-Ro-mediated decrease of [Ca2+]i level resulted from cAMP/PKA-pathway or cGMP/PKG-pathway, the G-Ro-reduced [Ca2+]i level would be increased by inhibitors of PKA or PKG. Accordingly, we investigated the effects of PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS and PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS on IC50 (155 μM) and 300 μM of G-Ro-reduced [Ca2+]i level, which is to observe an apparent elevation of [Ca2+]i by their inhibitors. As shown in Figure 4(b), the PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (50 to 250 μM) dose-dependently increased the [Ca2+]i level as compared with those (160.3 ± 7.1, 140.1 ± 1.8 nM) by G-Ro (155, 300 μM) in the thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (Figure 4(b)). As shown in Table 1, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM) increased G-Ro-decreased (155, 300 μM) [Ca2+]i levels to 103.6% and 85.8%, respectively. But Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (250 μM) increased G-Ro-decreased (155, 300 μM) [Ca2+]i levels to 26.4% and 36.9%, respectively (Table 1, Figure 4(c)).

Figure 4.

Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization. (a) Effects of G-Ro on [Ca2+]i level in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. (b) Effects of G-Ro on [Ca2+]i level in the presence of A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). (c) Effects of G-Ro on [Ca2+]i level in the presence of G-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cGMPS). [Ca2+]i was determined as described in “Section 2.” The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets, # p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (155 μM), and † p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (300 μM).

Table 1.

Effects of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS and Rp-8-Br-cGMPS on [Ca2+]i mobilization.

| [Ca2+]i (nM) | Increase (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| G-Ro (155 μM) + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 160.3 ± 8.1 | — |

| G-Ro (155 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM) + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 326.3 ± 9.0 | 103.6(1) |

| G-Ro (155 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (250 μM) + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 202.6 ± 4.6 | 26.4(2) |

|

| ||

| G-Ro (300 μM) + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 140.1 ± 1.8 | — |

| G-Ro (300 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM) + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 260.3 ± 9.9 | 85.8(1) |

| G-Ro (300 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (250 μM) + thrombin (0.05 U/mL) | 191.8 ± 7.3 | 36.9(2) |

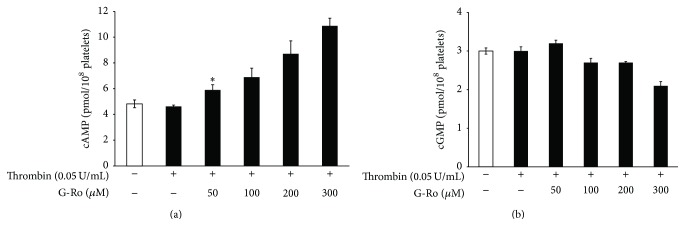

3.4. Effects of G-Ro on cAMP and cGMP Production

Because it was confirmed that inhibition of [Ca2+]i level by G-Ro is dependent on cAMP/PKA and cGMP/PKG, next, we investigated whether G-Ro increases cAMP and cGMP production in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. As shown in Figure 5(a), thrombin weakly decreased cAMP level, but G-Ro (50 to 300 μM) dose-dependently increased thrombin-attenuated cAMP level. With regard to cGMP, thrombin did not change cGMP level as compared with that of basal level; on the contrary, cGMP appears to be decreased by G-Ro (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

Effects of G-Ro on cAMP and cGMP production. (a) Effects of G-Ro on cAMP production in thrombin-induced platelets. (b) Effects of G-Ro on cGMP production in thrombin-induced platelets. cAMP and cGMP were determined as described in “Section 2.” The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets.

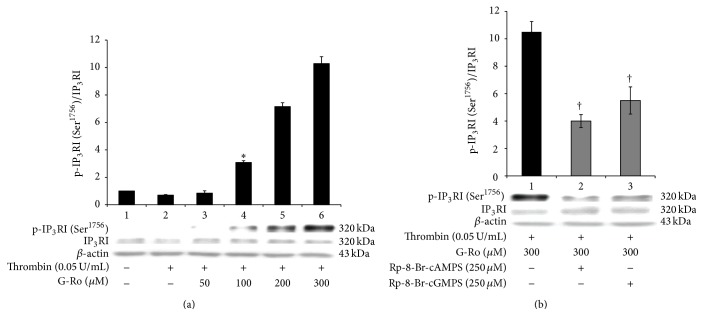

3.5. Effects of G-Ro on Inositol 1, 4, 5-Trisphosphate Receptor Type I (IP3RI) (Ser1756) Phosphorylation

G-Ro (50 to 300 μM) dose-dependently increased phosphorylation [IP3R (Ser1756)] of IP3RI (Ser1756) and the ratio of p-IP3RI (Ser1756) to IP3RI in thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation (Figure 6(a) Lanes 3 to 6). To know whether IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation by G-Ro was resulted from cAMP/PKA-pathway or cGMP/PKG-pathway, we investigated an apparent inhibitory effect of their inhibitors on IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation by 300 μM of G-Ro that potently stimulates the phosphorylation of IP3RI (Ser1756). As shown in Figure 6(b), Lane 2, PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS decreased G-Ro-increased p-IP3RI (Ser1756) in thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS also decreased G-Ro-induced p-IP3RI (Ser1756) (Figure 6(b), Lane 3). But inhibitory degree by PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS was lower as compared with that by PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS.

Figure 6.

Effects of G-Ro on inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor type I (IP3RI) (Ser1756) phosphorylation. (a) Effects of G-Ro on IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation. Lane 1, unstimulated platelets (base); Lane 2, thrombin (0.05 U/mL); Lane 3, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (50 μM); Lane 4, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (100 μM); Lane 5, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (200 μM); Lane 6, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM). (b) Effects of G-Ro on IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation in the presence of A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) and G-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cGMPS). Lane 1, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM); Lane 2, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM); Lane 3, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (250 μM). Western blotting was performed as described in “Section 2.” The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets; † p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (300 μM).

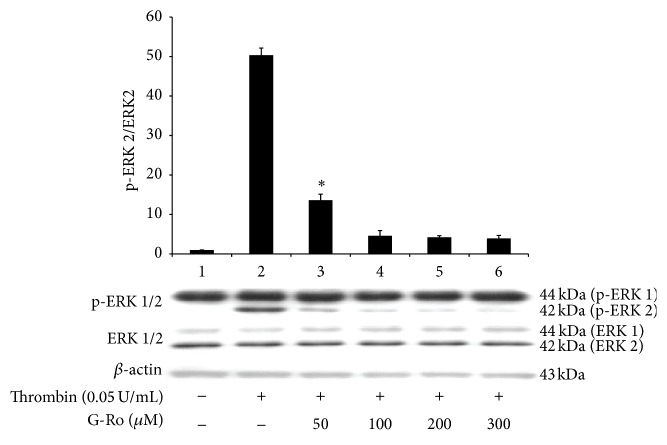

3.6. Effects of G-Ro on Dephosphorylation of ERK

It is known that Ca2+ mobilized from DTS (ER) is involved in phosphorylation of PI3K and ERK to influx extracellular Ca2+ [13, 14, 17, 18]. Here, we investigated the effect of G-Ro on dephosphorylation of ERK (1/2). As shown in Figure 7, in unstimulated platelets, ERK 1 (44 kDa) phosphorylation only was observed (Figure 7, Lane 1). Thrombin potently phosphorylated both ERK 1 (44 kDa) and ERK 2 (42 kDa) (Figure 7, Lane 2). However, G-Ro (50 to 300 μM) dose-dependently inhibited thrombin-induced phosphorylation of ERK 2 (42 kDa), and the ratio of p-ERK 2 to ERK 2 (42 kDa) (Figure 7, Lanes 3 to 6).

Figure 7.

Effects of G-Ro on dephosphorylation of ERK. Lane 1, unstimulated platelets (base); Lane 2, thrombin (0.05 U/mL); Lane 3, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (50 μM); Lane 4, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (100 μM); Lane 5, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (200 μM); Lane 6, thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM). Western blotting was performed as described in “Section 2.” The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets.

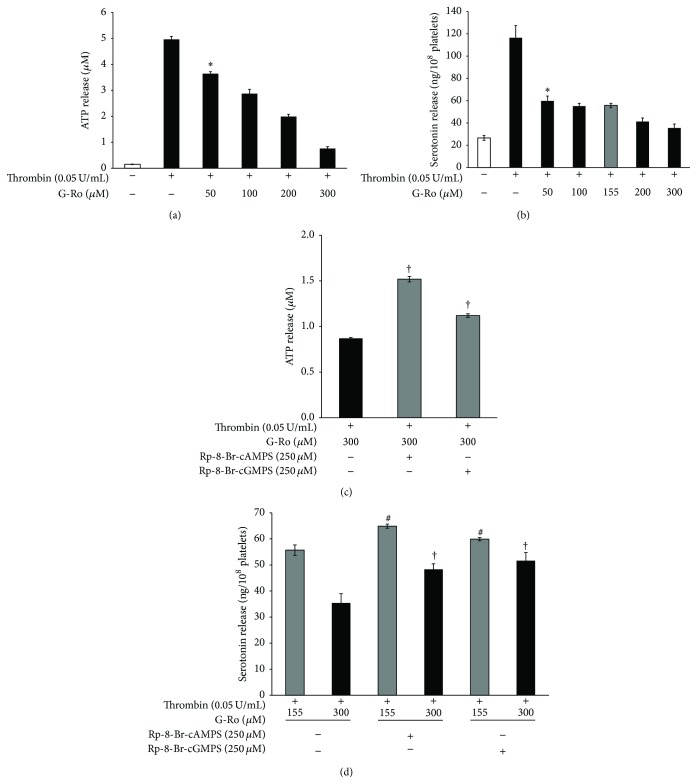

3.7. Effects of G-Ro on ATP and Serotonin Release from Dense Body

Dense body contains nucleotides (ATP and ADP) and serotonin; these are released by collagen- or thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i and subsequently involve amplification of platelet activation [33–36]. Because G-Ro decreased thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i level, we investigated whether G-Ro is involved in inhibition of ATP and serotonin release. G-Ro (50 to 300 μM) dose-dependently inhibited thrombin-induced ATP (Figure 8(a)) and serotonin release (Figure 8(b)). Next, we investigated whether the inhibition of ATP and serotonin release by G-Ro was dependent on cAMP/PKA-pathway and cGMP/PKG-pathway. G-Ro-downregulated (300 μM) release of ATP and serotonin was significantly increased in the presence of PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS and PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (Figure 8(c)). In addition, these inhibitors significantly elevated G-Ro-decreased (155, 300 μM) serotonin release (Figure 8(d)).

Figure 8.

Effects of G-Ro on ATP and serotonin release. (a) Effects of G-Ro on ATP release in thrombin-activated platelets. (b) Effects of G-Ro on serotonin release in thrombin-activated platelets. (c) Effects of G-Ro on ATP release in the presence of A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) and G-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cGMPS). (d) Effects of G-Ro on serotonin release in the presence of A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) and G-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cGMPS). Determination of ATP and serotonin release was carried out as described in “Section 2.” The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets, # p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (155 μM), and † p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (300 μM).

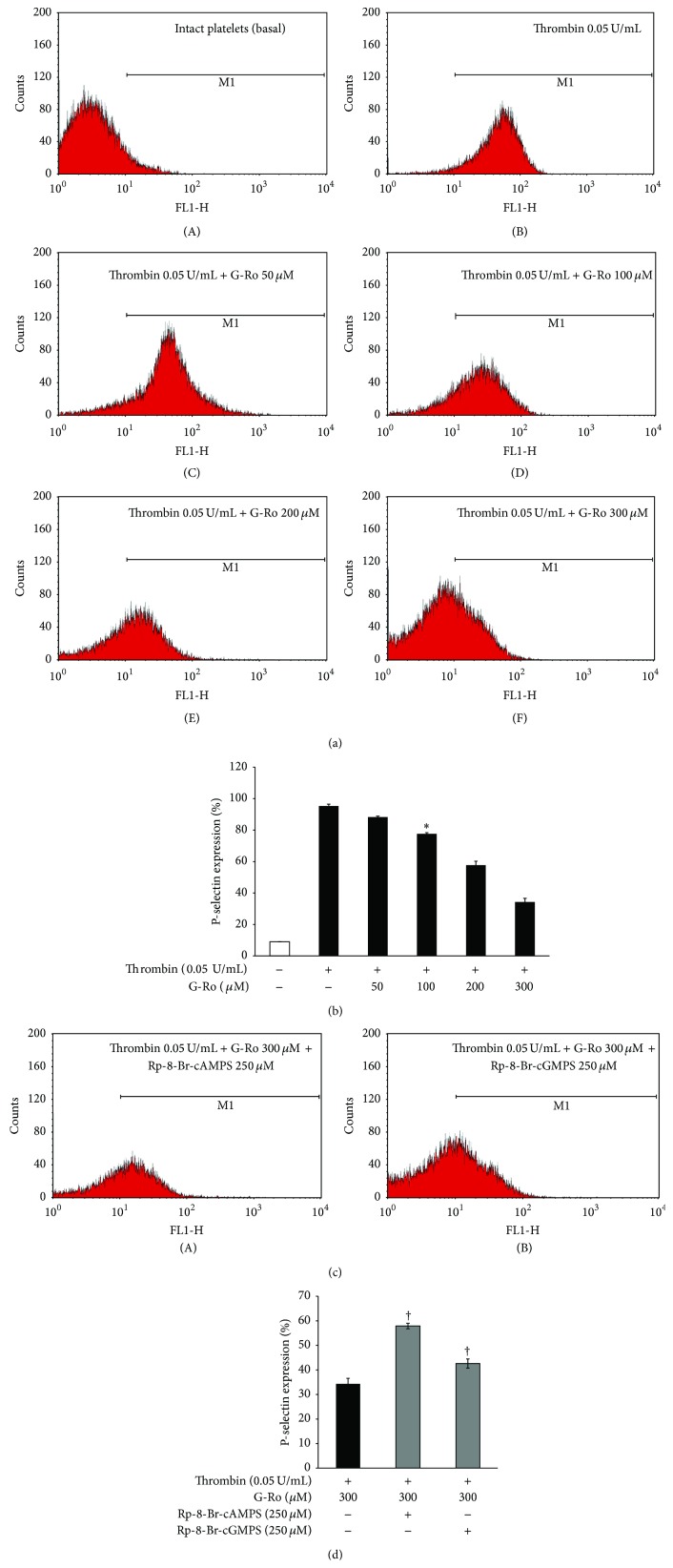

3.8. Effects of G-Ro on p-Selectin Expression

Compounds in α-granule of platelets are known to be involved in inflammation, coagulation, and angiogenesis [36]; these are also Ca2+-dependently released by various platelet agonists. In particular, p-selectin is released from α-granule and is reexpressed to the platelet surface [37] and subsequently is involved in inflammation by binding to the p-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 receptor on monocyte [38]. Therefore, we investigated the effect of G-Ro on p-selectin expression from α-granule. Thrombin stimulated the expression of p-selectin (Figure 9(a)-(B)) as compared with that by unstimulated platelets (Figure 9(a)-(A)). However, G-Ro (50 to 300 μM) dose-dependently inhibited thrombin-induced expression of p-selectin (Figures 9(a)-(C)~(F) and 9(b)). PKA inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS increased G-Ro-reduced (300 μM) p-selectin expression (Figures 9(c)-(A) and 9(d)), but PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS did not increase as compared with that by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Figures 9(c)-(B) and 9(d)).

Figure 9.

Effects of G-Ro on p-selectin expression. (a) The flow cytometry histograms on p-selectin expression. (A) Intact platelets (base); (B) thrombin (0.05 U/mL); (C) thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (50 μM); (D) thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (100 μM); (E) thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (200 μM); (F) thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM). (b) Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced p-selectin expression (%). (c) The flow cytometry histograms on p-selectin expression in the presence of A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) and G-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cGMPS). (A) Thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM); (B) thrombin (0.05 U/mL) + G-Ro (300 μM) + Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (250 μM). (d) Effects of G-Ro on thrombin-induced p-selectin expression in the presence of A-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) and G-kinase inhibitor (Rp-8-Br-cGMPS) (%). Determination of p-selectin expression was carried out as described in “Section 2.” The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). ∗ p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets; † p < 0.05 versus the thrombin-stimulated human platelets in the presence of G-Ro (300 μM).

4. Discussion

Thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i is involved in various cellular events to activate platelets, which leads to granule secretion and platelet aggregation. IP3 that is generated from PIP2 by agonists (i.e., thrombin, collagen, and ADP) mobilizes [Ca2+]i from Ca2+ store DTS via IP3RI. Depletion of the intracellular Ca2+ store by IP3 is known to connect the influx of extracellular Ca2+, which is stimulated by PI3K and ERK [14–18]. Even though G-Ro inhibited thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i, it is not unknown if G-Ro inhibited the production of IP3 via inhibition of phospholipase Cβ. The Ca2+-antagonistic reaction by cAMP and cGMP is mediated by PKA/IP3RI and PKG/IP3RI phosphorylation pathways, respectively. Even if G-Ro would not inhibit PLC-β activity and IP3 production in thrombin-activated human platelets, if G-Ro that elevates the level of cAMP stimulates IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation in thrombin-activated human platelets, this is a clear evidence that G-Ro is involved in inhibition of [Ca2+]i mobilization from DTS via cAMP/PKA/IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation pathway. In this report, we confirmed that G-Ro inhibited [Ca2+]i mobilization via IP3RI (Ser1756) phosphorylation by cAMP/PKA, which is supported from the result that cAMP inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS inhibited G-Ro-elevated phosphorylation of IP3RI (Ser1756) in thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation; if not so, A-kinase inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS would not increase G-Ro-decreased [Ca2+]i mobilization in thrombin-induced human platelet aggregation. It is well established that PI3K and ERK are involved in influx of extracellular Ca2+ across PM. Because Fura 2-loaded washed platelets were stimulated by thrombin in the presence of CaCl2 (2 mM), thrombin-evoked [Ca2+]i resulted from the Ca2+ mobilization from DTS by IP3 and the Ca2+ influx across PM by PI3K or ERK. Because G-Ro activated the phosphorylation of IP3RI (Ser1756) and the dephosphorylation of ERK 2 (42 kDa), the inhibition of thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i by G-Ro is thought to result from both phosphorylation of IP3RI (Ser1756) and dephosphorylation of ERK 2 (42 kDa) by G-Ro. It is known that IP3 induces serotonin release from platelet dense body, which means that IP3 is involved in serotonin release by elevating [Ca2+]i via IP3RI [39]. This reflects that G-Ro may be involved in inhibition of serotonin release by phosphorylating IP3RI (Ser1756).

A lot of agonists such as collagen, thrombin, and ADP increase [Ca2+]i to phosphorylate Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain (20 kDa), which is involved in granule secretion such as ATP and serotonin [8, 9] to intensify platelet aggregation. It is known that G-Ro does not reduce collagen-elevated [Ca2+]i level [40]; however, in this study, we confirmed that G-Ro decreases thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i level by stimulating the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of IP3RI (Ser1756) and dephosphorylation of ERK 2 (42 kDa). Therefore, it is thought that the inhibition of ATP and serotonin secretion by G-Ro resulted from the inhibition of IP3RI-mediated [Ca2+]i mobilization, and ERK 2-mediated (42 kDa) Ca2+ influx.

Platelet aggregation is generated at site of vascular wall injury and is involved in the formation of thrombus. During the formation of thrombus, platelets release cell growth proteins such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in α-granule [41, 42]. It is well established that PDGF and VEGF induce the proliferation of fibroblast, vascular smooth cells, and epithelial cells and subsequently enhance the rate of atherosclerosis lesion progression [43–47]. The progression of atherosclerosis is strongly induced by inflammatory cell such as monocyte/macrophage and neutrophil [48]. Although G-Ro has antiplatelet effects, if G-Ro does not inhibit inflammation by leukocyte, the progression of atherosclerosis lesion would be generated at site of vascular wall injury, and a question for antiplatelet effects of G-Ro might be raised. ATP and serotonin released from dense body are known to be involved in amplification of platelet aggregation [33–36], and p-selectin released from α-granule is known to be involved in causing of inflammation [36–38]. Because G-Ro inhibited the release of ATP, serotonin, and p-selectin, it is thought that G-Ro may inhibit aggregation-amplification and inflammation. In real, G-Ro is known to have anti-inflammatory activity in vivo and in vitro [49, 50]. It is well reviewed that ginsenosides have anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the production of various proinflammatory mediators (i.e., PGE2 and NO) [51]. With regard to the composition of G-Ro, Sanada et al. [19] reported that G-Ro is contained in Panax ginseng, and Choi [20] very well reviewed that G-Ro (0.045 w/w %) is contained in Panax ginseng, but not in Panax notoginseng (Sanchi ginseng). It has been reported that G-Ro inhibited arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation and fibrin formation in vitro [52] and activated fibrinolysis, indicating the inhibition of fibrin thrombi ex vivo [53].

Considering these previous reports [49–53], it is thought that G-Ro may have antithrombotic and antiatherosclerotic effects without generation of inflammation and progression of atherosclerotic lesion at site of vascular wall injury. Therefore, G-Ro is highlighted as a nontoxic antiplatelet compound together with effect that G-Ro did not affect LDH leakage.

In conclusion, the most important result of this study is that G-Ro cAMP-dependently phosphorylates IP3RI (Ser1756) and dephosphorylates ERK 2 (42 kDa) to reduce thrombin-elevated [Ca2+]i level, which contributed to attenuating the release of ATP, serotonin, and p-selectin. In addition, G-Ro could be clinically applied to the prevention of platelet-mediated thrombosis. Therefore, it is thought that G-Ro may represent a useful tool in the therapy and prevention of vascular diseases associated with platelet aggregation.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant (NRF-2011-0012143 to Hwa-Jin Park) from the Basic Science Research Program via the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Korea.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

Hyuk-Woo Kwon and Jung-Hae Shin contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Heemskerk J. W. M., Sage S. O. Calcium signalling in platelets and other cells. Platelets. 1994;5(6):295–316. doi: 10.3109/09537109409006439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rink T. J., Sage S. O. Calcium signaling in human platelets. Annual Review of Physiology. 1990;52:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sage S. O. The Wellcome Prize Lecture. Calcium entry mechanisms in human platelets. Experimental Physiology. 1997;82(5):807–823. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge M. J., Irvine R. F. Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature. 1984;312(5992):315–321. doi: 10.1038/312315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattaneo M. The P2 receptors and congenital platelet function defects. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 2005;31(2):168–173. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidetti G. F., Lova P., Bernardi B., et al. The Gi-coupled P2Y12 receptor regulates diacylglycerol-mediated signaling in human platelets. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(43):28795–28805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m801588200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings L. K. Role of platelets in atherothrombosis. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2009;103(3):4A–10A. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishikawa M., Tanaka T., Hidaka H. Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation and platelet secretion. Nature. 1980;287(5785):863–865. doi: 10.1038/287863a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaibuchi K., Sano K., Hoshijima M., Takai Y., Nishizuka Y. Phosphatidylinositol turnover in platelet activation; calcium mobilization and protein phosphorylation. Cell Calcium. 1982;3(4-5):323–335. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(82)90020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz U. R., Walter U., Eigenthaler M. Taming platelets with cyclic nucleotides. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;62(9):1153–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavallini L., Coassin M., Borean A., Alexandre A. Prostacyclin and sodium nitroprusside inhibit the activity of the platelet inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and promote its phosphorylation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(10):5545–5551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinton T. M., Dean W. L. Cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation of the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor inhibits Ca2+ release from platelet membranes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1992;184(2):893–899. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90675-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosado J. A., Sage S. O. Phosphoinositides are required for store-mediated calcium entry in human platelets. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(13):9110–9113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosado J. A., Sage S. O. Coupling between inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and human transient receptor potential channel 1 when intracellular Ca2+ stores are depleted. Biochemical Journal. 2000;350(3):631–635. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3500631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosado J. A., Sage S. O. The actin cytoskeleton in store-mediated calcium entry. The Journal of Physiology. 2000;526(2):221–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosado J. A., Sage S. O. A role for the actin cytoskeleton in the initiation and maintenance of store-mediated calcium entry in human platelets. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2000;10(8):327–332. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(01)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosado J. A., Sage S. O. Role of the ERK pathway in the activation of store-mediated calcium entry in human platelets. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(19):15659–15665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m009218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosado J. A., Sage S. O. The ERK cascade, a new pathway involved in the activation of store-mediated calcium entry in human platelets. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2002;12(5):229–234. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(02)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanada S., Kondo N., Shoji J., Tanaka O., Shibata S. Studies on the saponins of ginseng. I. Structures of ginsenoside-Ro, -Rb1, -Rb2, -Rc and -Rd. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1974;22(2):421–428. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi K.-T. Botanical characteristics, pharmacological effects and medicinal components of Korean Panax ginseng CA Meyer. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2008;29(9):1109–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst E. Panax ginseng: an overview of the clinical evidence. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2010;34(4):259–263. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2010.34.4.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S.-K., Park J. H. Trends in ginseng research in 2010. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2011;35(4):389–398. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2011.35.4.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung I.-M., Lim J. W., Pyun W.-B., Kim H. Korean red ginseng improves vascular stiffness in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2010;34(3):212–218. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2010.34.3.212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wee J. J., Kim Y. S., Kyung J. S., et al. Identification of anticoagulant components in Korean red ginseng. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2010;34(4):355–362. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2010.34.4.355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung Y. H., Park K. Y., Jeon J. H., et al. Red ginseng saponin fraction A isolated from Korean red ginseng by ultrafiltration on the porcine coronary artery. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2011;35(3):325–330. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2011.35.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang S.-Y., Son D. J., Kim I.-W., et al. Korean red ginseng attenuates hypercholesterolemia-enhanced platelet aggregation through suppression of diacylglycerol liberation in high-cholesterol-diet-fed rabbits. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(6):778–783. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee D.-H., Cho H.-J., Kang H.-Y., Rhee M.-H., Park H.-J. Total saponin from Korean Red Ginseng inhibits thromboxane A2 production associated microsomal enzyme activity in platelets. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2012;36(1):40–46. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teng C.-M., Kuo S.-C., Ko F.-N., et al. Antiplatelet actions of panaxynol and ginsenosides isolated from ginseng. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—General Subjects. 1989;990(3):315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(89)80051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus A. J., Zucker-Franklin D., Safier L. B., Ullman H. L. Studies on human platelet granules and membranes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1966;45(1):14–28. doi: 10.1172/jci105318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goode D. J., Meltzer H. Y. Cytotoxic effects of imipramine on platelets. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1974;23(18):2629–2635. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujiwara Y., Banno H., Shinkai Y., Yamamoto C., Kaji T., Satoh M. Protective effect of pretreatment with cilostazol on cytotoxicity of cadmium and arsenite in cultured vascular endothelial cells. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2011;36(2):155–161. doi: 10.2131/jts.36.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmsen H., Day H. J. The selectivity of the thrombin-induced platelet release reaction: subcellular localization of released and retained constituents. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1970;75(5):840–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mustard J. F., Packham M. A. Factors influencing platelet function: adhesion, release, and aggregation. Pharmacological Reviews. 1970;22(2):97–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charo I. F., Feinman R. D., Detwiler T. C. Inhibition of platelet secretion by an antagonist of intracellular calcium. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1976;72(4):1462–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(76)80178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broos K., Feys H. B., De Meyer S. F., Vanhoorelbeke K., Deckmyn H. Platelets at work in primary hemostasis. Blood Reviews. 2011;25(4):155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarbock A., Polanowska-Grabowska R. K., Ley K. Platelet-neutrophil-interactions: linking hemostasis and inflammation. Blood Reviews. 2007;21(2):99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davì G., Patrono C. Mechanisms of disease: platelet activation and atherothrombosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(24):2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/nejmra071014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Authi K. S., Evenden B. J., Crawford N. Metabolic and functional consequences of introducing inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate into saponin-permeabilized human platelets. Biochemical Journal. 1986;233(3):707–718. doi: 10.1042/bj2330707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng C.-M., Kuo S.-C., Ko F.-N., et al. Antiplatelet actions of panaxynol and ginsenosides isolated from ginseng. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—General Subjects. 1989;990(3):315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(89)80051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro-Malaspina H., Rabellino E. M., Yen A., Nachman R. L., Moore M. A. Human megakaryocyte stimulation of proliferation of bone marrow fibroblasts. Blood. 1981;57(4):781–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holash J., Maisonpierre P. C., Compton D., et al. Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science. 1999;284(5422):1994–1998. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagai R., Suzuki T., Aizawa K., Shindo T., Manabe I. Significance of the transcription factor KLF5 in cardiovascular remodeling. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2005;3(8):1569–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz S. M., Reidy M. A. Common mechanisms of proliferation of smooth muscle in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Human Pathology. 1987;18(3):240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Packham M. A., Mustard J. F. The role of platelets in the development and complications of atherosclerosis. Seminars in Hematology. 1986;23(1):8–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz S. M., Ross R. Cellular proliferation in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 1984;26(5):355–372. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(84)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seppä H., Grotendorst G., Seppä S., Schiffmann E., Martin G. R. Platelet-derived growth factor is chemotactic for fibroblasts. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1982;92(2):584–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.2.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips D. R., Conley P. B., Sinha U., Andre P. Therapeutic approaches in arterial thrombosis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2005;3(8):1577–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuda H., Samukawa K.-I., Kubo M. Anti-inflammatory activity of ginsenoside Ro. Planta Medica. 1990;56(1):19–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim S., Oh M., Kim B., et al. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 by ginsenoside Ro attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophage cells. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park J. S., Cho J. Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of ginsenosides from Panax ginseng and their structural analogs. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2009;8(16):3682–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuda H., Namba K., Fukuda S., Tani T., Kubo M. Pharmacological study on Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. III. Effects of red Ginseng on experimental disseminated intravascular coagulation. (2). Effects of ginsenosides on blood coagulative and fibrinolytic systems. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1986;34(3):1153–1157. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuda H., Namba K., Fukuda S., Tani T., Kubo M. Pharmacological study on Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer IV. Effects of red ginseng on experimental disseminated intravascular coagulation. (3). Effect of ginsenoside-Ro on the blood coagulative and fibrinolytic system. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1986;34(5):2100–2104. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]