Abstract

In utero, hypoxia is a significant yet common stress that perturbs homeostasis and can occur due to preeclampsia, preterm labor, maternal smoking, heart or lung disease, obesity, and high altitude. The fetus has the extraordinary capacity to respond to stress during development. This is mediated in part by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and more recently explored changes in perirenal adipose tissue (PAT) in response to hypoxia. Obvious ethical considerations limit studies of the human fetus, and fetal studies in the rodent model are limited due to size considerations and major differences in developmental landmarks. The sheep is a common model that has been used extensively to study the effects of both acute and chronic hypoxia on fetal development. In response to high-altitude-induced, moderate long-term hypoxia (LTH), both the HPA axis and PAT adapt to preserve normal fetal growth and development while allowing for responses to acute stress. Although these adaptations appear beneficial during fetal development, they may become deleterious postnatally and into adulthood. The goal of this review is to examine the role of the HPA axis in the convergence of endocrine and metabolic adaptive responses to hypoxia in the fetus.

Keywords: fetus, cortisol, adipose, hypoxia

mammalian fetuses, and in particular fetuses from long-gestational length pregnancies such as humans (primates) and ruminants, have the ability to respond to and/or adapt to stress during gestation to survive the potentially harsh intrauterine environment and continue to term. Postbirth, both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis via cortisol and the adrenomedullary/sympathetic nervous system via catecholamines serve as homeostatic regulators in response to acute and chronic stress. In larger mammalian fetuses, these systems exhibit maturation in late gestation and serve similar roles, providing the fetus with the means to respond to intrauterine stressors. Activation of these two mechanisms leads to rapid glucose, renal, and cardiovascular changes (35, 62, 88, 180) as well as slower adaptive modifications of gene expression to combat potential long-term effects (3, 4, 51, 120, 181). Although these responses to hypoxic stress may often be beneficial acutely, they have the potential to be deleterious, especially under sustained periods of hypoxic stress.

The influence of hypoxia during fetal development is of particular importance due to its potential to induce or “program” alterations in endocrinology and metabolism long after birth. It has been recognized for more than two decades that an “adverse intrauterine environment” could lead to offspring predisposed to a variety of related disorders, including cardiovascular disorder, metabolic disorder, and obesity as adults. This so-called programming, also referred to as the “fetal origins of adult disease hypothesis,” describes how an adverse intrauterine environment can trigger adaptive or maladaptive changes in the developing fetus to overcome the hostile conditions and survive (9, 12, 13, 15, 147). This adverse environment imprinted during development can increase the susceptibility of the fetus to acquire cardiovascular and metabolic pathologies later in life (10, 15–17, 45, 46, 97, 111). Although the original hypothesis was derived largely from observations of offspring from malnourished or undernourished pregnancies, later studies have expanded to include the impact of a variety of so-called intrauterine stressors. This has been reviewed in more detail by Godfrey and Barker (69) and Calkins and Devaskar (30).

Fetal hypoxia is a common stressor that occurs during pregnancy as the result of a variety of situations, including maternal under- or malnutrition, preeclampsia, preterm labor, smoking, heart or lung disease, obesity, and exposure to high altitude (14, 40, 48, 73, 91, 125, 150). Therefore, due to its prevalence, hypoxia likely plays a key role in the influence of an adverse intrauterine environment on the developing fetus. The impact of hypoxia on the fetus is dependent on a wide range of variables, including gestational age, severity, and duration of hypoxia, as well as confounders such as acidemia and hypercapnia.

When considering changes in response to hypoxic stress, the HPA axis is key due to its role in growth and maturation of the fetus. The HPA axis, through regulation of glucocorticoid biosynthesis (138, 157), dictates differentiation and maturation of key organ systems, including lung, liver, and kidney, and regulation of metabolism, including lipolysis, glycogenolysis, and protein catabolism (37, 108, 115). Acutely, activation of the HPA axis leads to a significant increase in cortisol (2, 23, 24, 80, 87), a glucocorticoid that plays a critical role in governing metabolism by influencing plasma glucose, lipid, and protein concentrations as well as immune regulation, inflammation, and cardiovascular function. Under chronic stress conditions, cortisol production is associated with hyperglycemia, immune suppression, excess adipose deposition, bone loss, and hypertension (38, 148, 169). Therefore, the ability of the fetal HPA axis to adapt to limit cortisol production under conditions of chronic stress is crucial for maintaining normal development during gestation. The HPA axis must mature to permit the normal ontogenic rise in cortisol in preparation for birth (19, 76, 105, 126, 138, 157) while allowing for an acute response to a secondary stressor.

Another key regulatory mediator influenced by hypoxia in the fetus is perirenal adipose tissue (PAT). In sheep, ∼80% of fetal adipose tissue deposition occurs in the perirenal-abdominal region (165). During late gestation, fetal mass expands and adipose tissue develops and responds to hormonal and nutritional perturbations that can alter lipid storage and release as well as induce secretion of leptin (140). Early changes in adipose function in response to hypoxia may play a role in fetal programming due to the influence of leptin and gene expression on metabolic processes and the possible overlap between leptin and cortisol regulation.

One of the biggest roadblocks to advancement of our understanding of fetal adaptive responses to hypoxia is an appropriate model. Because of obvious ethical considerations, there are little data on the effect of hypoxia on endocrine and metabolic alterations in human fetuses. Additionally, although there are programming studies of the effects of hypoxia in rodents, due to the small size and developmental maturity of the fetus, they are not ideal for fetal endocrine and metabolic studies. Fetal studies have also been conducted in nonhuman primates, but they are limited due to the tremendous cost and lack of availability of animals. The sheep has become a major animal model for studying the impact of hypoxia on the developing fetus due to its relatively long gestational period, similarity of endocrine and physiological systems, and relative ease of fetal and maternal instrumentation.

Throughout this review, we will highlight key findings in relation to the impact of hypoxia on the complex interactions between the endocrine and metabolic responses of the fetus in the fetal HPA axis and PAT. Although as described previously the majority of information has been derived from studies utilizing the ovine fetus, wherever possible we will draw correlates from human and nonhuman primate studies.

Acute Hypoxia

As described above, from a clinical perspective, fetal hypoxia can occur as a result of a wide range of maternal conditions. In an effort to mimic some of these conditions, multiple models of hypoxia have been developed, varying in degree and duration. Acute hypoxia can be induced through maternal hypoxia (6, 42), blood flow restriction (ischemia) (177), or umbilical cord occlusion (UCO; asphyxia) (63, 70, 172) for a duration of a few minutes to several hours. Differential responses may occur in response to varying degrees of altered Po2, and hypoxia ischemia may be associated with metabolic changes; however, the key activator of the fetal stress response is the decrease in Po2. In response to acute hypoxia, there is a rapid release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP) from the hypothalamus, which triggers adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion from the anterior pituitary, followed by glucocorticoid production in the fetal adrenal cortex, proportional to the degree and duration of hypoxia. This swift response of the HPA axis to acute stress emphasizes the critical role glucocorticoids play in limiting the physiological impact of stress and maintaining fetal homeostasis.

Several studies conducted in the fetal sheep examined the effects of acute hypoxemia induced by reduction in maternal oxygen or by restriction of uteroplacental blood flow by UCO. Akagi and Challis (6) showed that moderate maternal hypoxia (Po2 reduced by 8.4 mmHg) for 1 h increased fetal plasma AVP and ACTH in 106- to 117-days gestation (dG) fetuses. In later-gestation fetuses (131 dG), Unno et al. (172) observed increased fetal plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations following a 50% reduction in blood flow by UCO. Furthermore, several studies found that acute episodes (1–48 h) of fetal hypoxemia (induced by maternal hypoxia or UCO) resulted in increased CRH mRNA in the fetal hypothalamus, proopiomelanocortin (POMC) mRNA in the fetal pituitary, and increased circulating AVP, ACTH, and cortisol concentrations in fetal plasma (7, 24, 26, 36, 87, 106, 129, 149, 161). Although the response of the HPA axis to stress is best seen in the late-gestation fetus, as the fetal HPA has matured and become fully responsive (58), changes in fetal plasma cortisol concentrations in response to acute hypoxemia have been reported in the ovine fetus as early as 120 dG (23). Together, the results of these studies exemplify the integrated response of the HPA axis to acute hypoxic stress.

While the response to an acute hypoxic insult results in upregulation of the HPA, prolonged elevated cortisol levels lead to fetal growth restriction and, in ruminants, activation of the parturition cascade and early birth of the small fetus (66, 154). To further examine the effects of hypoxia as a fetal stress, the response of the fetal HPA axis to repeated hypoxic perturbations or prolonged hypoxia over the course of several days has been investigated. Unno, et al. (172) found that after repeated UCOs, fetal anterior pituitary responsiveness was maintained with increased levels of plasma ACTH released after each UCO, but adrenocortical responsiveness was blunted; despite elevated ACTH, cortisol levels remained similar to basal levels by the 12th UCO. Green et al. (70) subjected 112- to 116-dG fetal sheep to repeated UCOs and saw increased plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations, but this response was attenuated after 4 days. These studies show that whereas fetal CRH/AVP and ACTH remained elevated in fetal plasma, cortisol returned to basal levels by the end of the hypoxic insult.

As term approaches, glucose production increases as cortisol and catecholamine concentrations increase in the fetus (57). In its role as a glucocorticoid, cortisol regulates metabolism by influencing plasma glucose concentrations. Along with cortisol, plasma glucose levels and fetal growth and development are also regulated by insulin, a hormone secreted from pancreatic β-cells in response to increased plasma glucose concentrations that stimulates cellular uptake of glucose (56). Insulin secretion is tightly coupled to plasma glucose concentration, maintaining a relatively constant insulin-to-glucose ratio. However, in response to an acute hypoxic challenge, several studies found that the fetus had decreased insulin secretion (18, 84, 182) accompanied by increased norepinephrine and epinephrine secretion (18, 41) and increased cortisol and corticosterone secretion (83). Further studies showed that hypoxic stress acts through an α2-adrenergic mechanism to induce inhibition of insulin secretion (82, 84, 98, 158). Jackson et al. (82) showed that acute hypoxemia (2 h, 126–128 dG) in the sheep fetus resulted in increased catecholamine secretion and reduced insulin concentrations, suggesting that fetal insulin production is mediated in part through sympathoadrenal stimulation. Together these studies suggest that glucocorticoids and catecholamines play a role in regulating insulin and glucose in response to hypoxia. Limesand et al. (100) observed that the increase in glucocorticoid elevated plasma glucose and circulating catecholamines prevented hyperinsulinemia, but together they resulted in hyperlactacemia and hypocarbia, showing a direct impact on fetal metabolism. In response to hypoxia, however, gluconeogenesis was initiated, and the excess lactate generated was used as a substrate for hepatic glucose production (100). This sympathoadrenal suppression of insulin secretion may act as a mechanism to conserve glucose and oxygen for essential organs such as the brain and heart (28, 64) but if sustained could result in reduced birth weight (82). In the human fetus, Zamudio et al. (187) found that women living at high altitude experienced chronic hypoxia that resulted in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), which was potentially initiated by fetal hypoglycemia; there were decreased circulating fetal glucose concentrations and consumption. This suggests altered placental metabolism that spares oxygen for fetal use but limits glucose availability for fetal growth. IUGR as a result of altered glucose metabolism has also been reported in a rat model of hypoxia by Lueder et al. (104). They observed that maternal exposure to 5 days of 10% ambient oxygen in the third trimester resulted in similar fetal plasma glucose concentrations between hypoxic and control but increased relative glucose utilization of hypoxic fetal tissues accompanied by acidosis, suggesting anaerobic metabolism and increased glycolysis in the hypoxic fetus.

In response to changes in metabolism, cortisol works to restore homeostasis to allow for the continued growth and development of the fetus. In the case of recurring acute hypoxic stress, continuous bursts of cortisol can become detrimental to fetal development, as excess glucocorticoids have been shown to lead to a growth-restricted fetus that is often delivered preterm (20, 66, 113, 127, 141, 154, 172). From these results, the ovine fetus has demonstrated an adaptation in the HPA axis, where there is dissociation in the response between the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and the adrenocortical response to brief repeated hypoxic stress or prolonged hypoxia over several days. Whereas CRH/AVP and ACTH levels remain elevated, cortisol returns to basal levels to allow for normal growth and development of the fetus.

Chronic Hypoxia

Experimentally, chronic hypoxia (over days to weeks or even months) can be initiated early or late in gestation and can be induced through placental embolization (29, 61), placental restriction, secondary to nutrient restriction (53, 143), or by high altitude resulting in moderate continuous hypoxia with normal pregnancy duration and no accompanying growth restriction (2, 75, 80, 89). Because the HPA axis matures in the latter third of gestation and increases in responsiveness as the fetus nears term (32, 95, 96, 124, 132, 134, 146, 173), studies often measure the effects of hypoxia in late gestation.

Gagnon et al. (61) and Murotsuki et al. (116) examined the effects of fetal placental embolization (30% reduction in arterial Po2) for 10 days in 122-dG sheep. It resulted in progressive hypoxemia with reduced fetal plasma ACTH but increased prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and maintained cortisol (61, 116). Infusions of PGE2 have been shown to increase cortisol levels in fetal sheep (78, 99, 103, 167, 168, 183, 184), and PGE2-induced cortisol production was not affected by hypophysectomy (99). This suggests that PGE2 may be involved in an adaptation to maintain basal fetal cortisol levels when ACTH is reduced and indicates that additional factors other than ACTH play a role in regulating cortisol production in the ovine fetus.

Another method of experimentally induced chronic hypoxia is through placental restriction (PR) via caruncletomy (143, 145). Phillips et al. (135) performed caruncletomies prior to mating to reduce the number of placentomes formed in ewes. This resulted in gestational hypoxia, with fetal arterial Po2 reduced by 30%. This highly successful model by Phillips et al. (135) allows for hypoxia throughout the entire course of gestation. However, the hypoxia is accompanied by nutrient restriction and IUGR. Due to PR-induced hypoxia, there was decreased POMC mRNA in the fetal pituitary and higher cortisol levels compared with control despite similar levels of plasma ACTH at 140 dG (135). From these results, they hypothesized that the HPA axis adapts to operate at a new set point in the growth-restricted fetus in response to nutrient restriction.

The fetal response to stress includes changes in cardiovascular and metabolic elements regulated by catecholamines (3, 43, 130, 136). Regulation of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), the enzyme responsible for catecholamine production, is classically thought to be affected by glucocorticoids in most species (21, 166, 179), with increases in glucocorticoid stimulating PNMT expression in adrenomedullary cells (105, 159, 174). However, in growth restriction models of hypoxia via carunclectomy, Coulter et al. (44) showed that dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) and encephalin-containing peptide immunostaining was decreased, and Adams et al. (4) observed decreased PNMT expression. In high-altitude induced long-term hypoxia (LTH), fetal plasma epinephrine concentrations were shown to be attenuated in response to superimposed acute hypoxia compared with normoxic controls despite similar basal plasma catecholamine levels, with no changes in norepinephrine (90). Glucocorticoid receptor expression was unaffected by LTH in the adrenal medulla; however, there were deficits in catecholamine biosynthesis and decreased expression of PNMT, tyrosine hydroxylase, and DBH that may be due to decreased nicotinic receptor subunit expression in the LTH fetal adrenal (51). These changes in catecholamine regulation indicate reduced sensitivity to glucocorticoids in the LTH fetus and could affect the transition from fetus to newborn, impacting both metabolism and cardiovascular function.

The effects of chronic hypoxia have also been investigated in a high-altitude-induced LTH ovine model, where ewes are maintained at 3,820 m beginning at approximately day 40 of gestation and continuing through to near-term (139–141 dG, term is ∼145 days, hypoxic fetal Po2 is ∼18 mmHg, and normoxic is ∼23 mmHg). In this model, the fetus has adapted to hypoxia such that pregnancies are of normal duration, fetuses are not growth restricted, and there is no accompanying acidosis (75, 89). Initial studies examining the effects of LTH on the ovine fetus showed that basal immunoreactive ACTH and cortisol concentrations were similar to normoxic control fetuses (75, 118). However, subsequent studies revealed that LTH stimulated hypothalamic drive, which enhanced expression of POMC and processing to ACTH with increased concentrations of ACTH1–39 and key POMC precursors (POMC and 22-kDa ACTH) in plasma (118). Despite higher basal levels of ACTH1–39, cortisol concentrations were not increased above normoxic controls in near-term fetuses.

This apparent discordance between elevated ACTH and normal basal cortisol levels became even more interesting in response to a superimposed acute secondary stressor. Surprisingly, in the LTH fetuses in response to hypotension or UCO, both ACTH and cortisol increased, but the cortisol response was greater compared with the response in normoxic fetuses (2, 80, 117). Further studies by Myers et al. (120) demonstrated reduced expression of ACTH receptor (ACTH-R),CYP17, and CYP11A1 with no changes in CYP21 or steroidogenic acute regulator (StAR) in the late-gestation LTH fetal adrenal cortex compared with normoxic controls. This suggests that reduced steroidogenic capacity in the LTH fetus may play a role in the apparent disconnect between basal ACTH and basal cortisol levels. However, mechanisms must exist to allow for a heightened cortisol response to acute stress despite the lowered expression of these key steroidogenic enzymes. The fetus has developed such that, despite elevated basal plasma ACTH, normal ontogenic maturation of cortisol production is maintained and the prepartum exponential rise is preserved (75), as well as the capacity to respond to an acute secondary stress (2). These adaptations indicate that the hypothalamic-pituitary portion of the axis responds to hypoxia as a stress by increasing the synthesis and release of ACTH secretagogues and activating the stress response. However, adaptive responses at the level of the adrenal cortex suppress excess stimulation under basal conditions.

As described above, in the LTH fetal adrenal cortex, there is decreased expression of CYP11A1 and CYP17, two key enzymes mediating cortisol synthesis, as well as decreased ACTH receptor expression (120). The reduction of these factors would result in attenuated adrenal responsiveness to ACTH and limited cortisol production. Along with these changes, however, there is an increase in the spent form of StAR protein (30 kDa), indicating increased transport of cholesterol into the inner mitochondrial membrane for the first step in cortisol biosynthesis. This could balance the adaptations of elevated basal plasma ACTH1–39 but reduce adrenal responsiveness to maintain basal levels of plasma cortisol similar to those observed in normoxic fetuses. In the LTH adrenal cortex, there are no changes in splicing factor-1 (SF-1) or DAX-1 expression, key transcription factors for ACTH-R, CYP11A1, and CYP17. This suggests that activation of these transcription factors is altered possibly via phosphorylation state or increased recruitment of corepressors (155).

The mechanisms involved in these adaptations have not been fully elucidated; however, nitric oxide (NO) may play a major role in regulating cortisol production intracellularly in the LTH fetal adrenal cortex. Tsubaki et al. (170) examined adrenal tissue and observed increased expression of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) in adrenal tissue that colocalizes with CYP17 in LTH fetuses, suggesting that NO plays a role in regulation of adrenal steroidogenesis. Monau et al. (109) also showed that eNOS is the dominant NOS isoform in the ovine fetal adrenal cortex, and eNOS mRNA and protein expression are increased in the LTH adrenal primarily in CYP17-expressing cells in the cortisol-producing zona fasciculate. Subsequent studies by Monau et al. (110) showed that NO reduced ACTH-mediated cortisol production in LTH fetal adrenocortical cells (FACs) in vitro, whereas inhibition of NOS activity increased cortisol production in LTH cells, with no effect on normoxic cells. Furthermore, ACTH reduced eNOS activation via phosphorylation in LTH FACs (123) and NO-dependent inhibition of ACTH-induced cortisol production, which further supports the role of NO in regulating cortisol production in the LTH fetal adrenal (171). This may be possible by NO competing with the oxygen-binding site of CYP11A1 and CYP17 (74, 170), disrupting the heme-oxygen complex attack by the enzyme on the steroid substrate. The increased release of NO under basal conditions would limit cortisol synthesis, whereas elevated ACTH release and signaling due to a secondary stress would inhibit NOS activity and remove NO inhibition, resulting in enhanced cortisol production in the LTH fetus. This provides a mechanism (NO) for the capability of the LTH fetus to overcome the reduced steroidogenic enzyme gene expression and mount an enhanced cortisol response to acute stressors. However, the question remains as to what factor(s) is involved in the decreased expression of the key steroidogenic machinery in response to LTH. Contributing to the changes in eNOS expression and activation, extracellular mechanisms, like those mediating endothelial and vascular responses to hypoxia such as VEGF or NF-κB as well as intracellular upstream factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), may play a role in regulating the fetal adrenal response to LTH (22, 27, 33, 60, 131, 142, 156, 175). However, these mechanisms are relatively unexplored in the fetal adrenal, and further investigations into the mechanisms involved in regulating eNOS activity and NO interactions with cortisol production are needed.

PAT and Leptin

One factor that may play a role is leptin. This 16-kDa protein derived from adipose tissue is most widely recognized for its role in appetite regulation in the adult (5, 86). However, leptin has also been clearly demonstrated to regulate adrenal steroid biosynthesis. In adult bovine adrenocortical cells, leptin suppressed cortisol output in response to ACTH stimulation, and this effect was mediated through a reduction in CYP17 and CYP11A1 expression (25, 93). Furthermore, leptin is a hypoxia-inducible gene (102). This adipocyte-derived hormone, like in human fetuses (101), circulates in the fetal sheep and increases in abundance in perirenal adipocytes as gestation progresses (185, 186). As in other metabolic tissues, maternal conditions and intrauterine stressors, such as hypoxia, influence fetal PAT.

In sheep, similar to the human, ∼80% of fetal adipose tissue deposition occurs in the perirenal-abdominal region (137, 139, 140, 164). Fetal PAT differentiation is initiated in midgestation and expands during late gestation with a concomitant increase in hormone receptor populations (140). Importantly, this adipose tissue depot works as an endocrine organ to produce leptin (140). As PAT begins to develop, it also responds to hormonal and nutritional perturbations in the fetus, which in turn affects lipid storage and release.

The extracellular regulation of cortisol and the fetal response to hypoxia may be regulated by leptin along with the intracellular regulation of cortisol production by NO in the fetal adrenal, as described above. When infused into the late-gestation ovine fetus, leptin attenuated the prepartum increase in fetal plasma ACTH and cortisol (79, 107, 186). Ducsay, et al. (50) found that plasma leptin was elevated in the LTH fetus compared with normoxic controls, with PAT and placenta expressing higher levels of leptin mRNA. Also, OB-Ra (the inactive short isoform) leptin receptor expression was reduced in the LTH hypothalamus, whereas OB-Rb (the active long-form isoform) expression was increased in the adrenal (50), suggesting the potential for enhanced leptin activity in the fetal adrenal. Thus, leptin appears to be a hypoxia-inducible gene in the ovine fetus with the capacity to inhibit cortisol biosynthesis at the adrenocortical level.

Subsequent studies showed that StAR, ACTH-R, CYP11A1, and CYP17 expression were lower in the LTH fetus (49) and that a 96-h leptin infusion into late-gestation spontaneously hypoxemic fetal sheep downregulated CYP21 mRNA and ACTH-R and StAR mRNA and protein (160), indicating reduced adrenal responsiveness and a reduced capacity to produce cortisol. A 4-day infusion of a leptin receptor antagonist restored expression of CYP11A1 and CYP17 in the LTH fetus to levels similar to normoxic but did not affect fetal plasma ACTH or cortisol (49), demonstrating that LTH regulation of leptin can influence adrenal steroidogenic enzyme expression.

Although leptin plays a role in regulating the response of the HPA and adipose tissue to chronic stress, it appears to work alongside cortisol and the adrenal to facilitate the fetal adaptation to hypoxia. Understanding the role of leptin in the intrauterine environment and the influence it has on the fetal HPA axis will help determine the long-term metabolic consequences of early life events and may include the ability of leptin to influence the development of obesity and its comorbidities.

Metabolic Gene Expression

Along with the production of leptin, other factors in adipose tissue are affected by hypoxia and may have a metabolic impact on the fetus. In the fetal sheep, as well as in the human, PAT has classically been considered a brown fat deposit [brown adipose tissue (BAT)]. It expresses uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) (34, 39, 47), which increases proton conduction of the inner mitochondrial membrane and catalyzes adaptive thermogenesis (31, 163). This enables the rapid generation of a significant amount of heat, and expression is most abundant in the newborn (163).

The fetal perirenal adipose depot in the LTH fetus, however, has been characterized with an unusual brown fat phenotype; there are mixed populations of multilocular deposits typical of white fat and unilocular fat deposits that are more common in brown fat. Leptin expression is more typical of white fat, and it is equally distributed in unilocular and multilocular adipocytes, with UCP1 staining distributed throughout the PAT. This unique phenotype has been termed “beige” fat, with white adipose tissue (WAT; myf +5 lineage) expressed as BAT (myf −5) (34, 47, 71, 81, 133, 151). Within PAT, Myers et al. (119) showed upregulation of UCP1, deiodinase 2 (DIO2), 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (11β-HSD1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ, and PPAR coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) mRNA. LTH appears to enhance brown fat functionality through upregulation of these hallmarks of the brown fat phenotype. Increased 11β-HSD1 and DIO2 would allow adipose tissue to increase the BAT phenotype without systemic increases in cortisol or triiodothyronine (T3), preventing deleterious effects on fetal growth and organ function. Along with upregulated brown fat gene expression, Myers et al. (121) found increased mRNA of transcription factors that regulate expression of NRF2 and mtTFA, genes that govern mitochondrial function, further indicating a BAT phenotype. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) has also been shown to enhance the beige/BAT phenotype of adipose tissue (55), and LTH enhanced hepatic FGF21 expression coupled with enhanced expression of FGF21 receptors in PAT (Myers DA and Ducsay CA, unpublished observations). This could serve as another mechanism of LTH-induced enhancement of changes in PAT.

The fetal adaptation to LTH in adipose tissue appears to involve increased leptin production and regulation of basal cortisol, as described above, as well as enhanced activation of adipose tissue. In the newborn, abdominal adipose is important for nonshivering thermogenesis and is regulated by UCP1 (31, 163). By increasing UCP1 expression, the fetus ensures adequate thermogenesis in the event of birth into oxygen-limited conditions. UCP1 expression is regulated by cortisol and T3 (67, 114), and increases in 11β-HSD1 and DIO2 indicate increased capacity for local synthesis and regulation by these hormones in the adipose tissue. This enhanced brown fat phenotype in anticipation of birth into a potentially hostile environment creates a balance between the upregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis while downregulating adrenal responsiveness to maintain basal cortisol levels.

These changes in the LTH fetus, however, are not maintained postnatally. After birth, LTH lambs lose their brown fat phenotype; Ducsay et al. (52) and Symonds et al. (163) showed that expression of UCP1, PGC-1α, and PR domain-containing protein 16 (PRDM16) decrease postbirth, implying a lineage derived from WAT and not BAT. Although the beige fat phenotype is initially protective of adiposity, decreases in UCP1, PGC-1α, and PRDM16 suggest a predisposition of the lamb to fat deposition. In the transition from fetus to neonate, there is a shift toward an enhanced white fat phenotype that may result in greater adiposity as the newborn matures; decreased BAT has been shown to result in obesity and related metabolic disorders that develop later in life (77, 81, 152).

The combined increased PAT expression and release of leptin, increased adrenocortical leptin receptor (OB-Rb) expression, and increased zona fasciculata-specific eNOS expression and activity (NO release) would limit the ability of elevated fetal plasma ACTH to stimulate cortisol production under basal conditions. Overcoming these mechanisms may allow for increased synthesis and release of cortisol in response to an acute secondary stressor.

Conclusions

The influence of hypoxia on the developing fetus has clearly been shown in the HPA axis and adipose tissue in the ovine model. A variety of other studies have shown changes in response to hypoxia in the macaque as well as the human. Hypoxia in the human fetus has been associated with both maternal and fetal conditions, including high altitude, maternal heart disease or pulmonary hypertension, preeclampsia, and placental insufficiency. These conditions often result in IUGR, preterm delivery, or stillbirth (1, 65, 72, 73, 85, 94, 112, 122). Maternal smoking also leads to hypoxia in the human and has been associated with IUGR (8, 54, 92, 144, 176, 178), and low birth weight is a significant risk factor for the development of obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes (11, 14, 68, 69, 128, 153). Studies in a nonhuman primate model, Japanese macaques, show that a high-fat diet reduces uterine volume blood flow, resulting in undernourished fetuses and an increased incidence of stillbirth (59). These studies show a dramatic effect of hypoxia on the growth potential of the fetus by either preventing full development or predisposing the fetus to numerous detrimental disorders.

The sheep has emerged as a major model for studying the effects of hypoxia on the fetus. When challenged with an acute stress, the fetal HPA axis is activated to release cortisol to counteract the perturbation and return the fetus to homeostasis. Sympathoadrenal inhibition of insulin secretion in response to hypoxia ensures adequate glucose for essential functions to restore homeostasis. In the case of a chronic stress such as long-term hypoxia, several studies have shown the remarkable ability of the fetus to adapt to circumvent growth restriction and preterm birth.

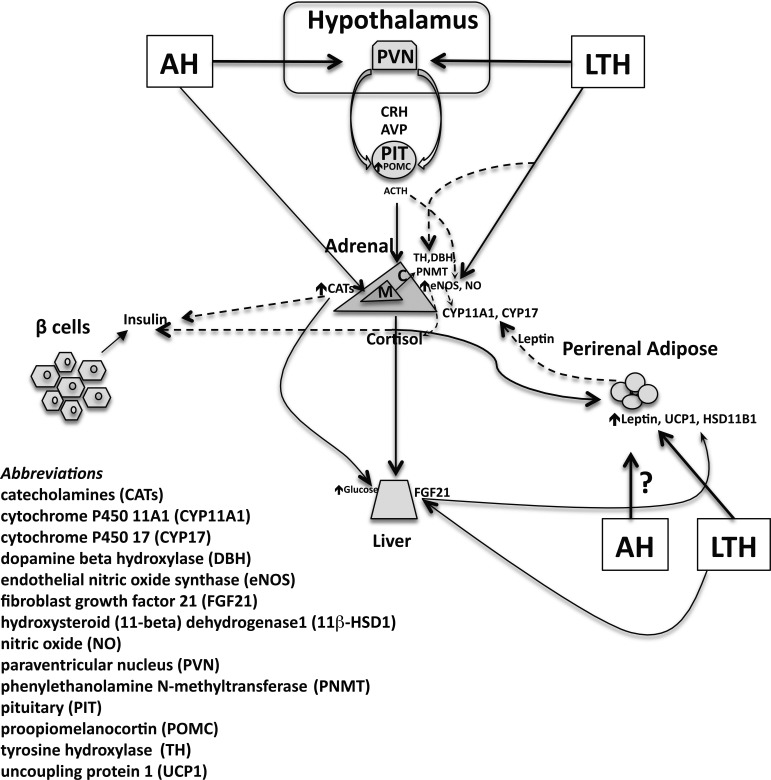

Hypoxia is a potent stressor that commonly affects the developing fetus and can result in adaptations in both the HPA axis as well as the adipose tissue. This complex interplay is summarized in Fig. 1, which illustrates the effects of both acute hypoxia and LTH. In the LTH fetus, the HPA adapts such that despite the upregulation of hypothalamic CRH/AVP and pituitary ACTH under basal conditions, adrenal production of cortisol is maintained at normoxic levels. However, in response to an acute secondary stressor, the production of cortisol is enhanced beyond the stress response in normoxic controls. This proposes an adaptation of the system that maintains cortisol levels required for growth and development but is combined with a programmed heightened response to acute stress. This mechanism may be mediated by NO production in adrenal cortical cells as well as by leptin production in fetal PAT.

Fig. 1.

Adaptive responses of the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to hypoxia. The diagram summarizes endocrine and metabolic adaptations to both acute (AH) and long-term hypoxia (LTH). The solid-line arrows illustrate stimulatory effects, whereas the dashed-line arrows denote inhibitory influences. CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; AVP, arginine vasopressin.

In this review, we have described the novel roles of NO and leptin in regulating cortisol biosynthesis in the LTH fetal adrenal. As described above, both NO and leptin appear to play significant roles in regulating the fetal adaptation to chronic hypoxia. NO seems to work via intra-adrenal regulation, potentially inhibiting steroidogenic enzyme activity via competition at the heme-oxygen binding site of CYP11A1 and CYP17 (74, 170) to inhibit cortisol biosynthesis. This inhibition is overcome by dramatically elevated stress levels of ACTH, resulting in reduced NOS activity and enhanced cortisol production (110). Leptin may function via extra-adrenal regulation, reducing steroidogenic enzyme expression (25, 93) and possibly inhibiting glucocorticoid secretion (186). Together, these factors work at the level of the adrenal to facilitate appropriate cortisol responses both in the normal ontogenic rise near term and in response to a secondary stress. Both NO and leptin are capable of inhibiting cortisol synthesis; however, the exact mechanisms are still undetermined. Further studies investigating the mechanisms responsible for these changes in the fetal HPA axis in response to chronic hypoxia and the coordination of NO and leptin to allow for normal fetal growth and development will help determine how the fetus survives and continues to term.

In adipose tissue, there is a unique beige phenotype developed in response to LTH. There is an upregulation of expression of the BAT phenotypic genes UCP1, DIO2, 11β-HSD1, PPARγ, and PGC-1α that would ensure adequate nonshivering thermogenesis and indicate reduced adiposity. These genes, however, become downregulated after birth, shifting toward a WAT phenotype and predisposing the newborn to fat deposition. If the fetus was born into a hypoxic environment, this adaptation would be beneficial, but in a normoxic environment this could have a significant detrimental lifelong impact resulting in a variety of metabolic disorders, including obesity and diabetes.

The interactive adaptive responses at the level of the HPA axis and adipose tissue play a key role in the immediate response to hypoxia. It will be important to determine whether these systems are a unique response to LTH or are invoked as a general adaptive response to other intrauterine stressors that aid in fetal survival. More critically, however, will be our ability to determine the mechanisms involved in the adaptive responses to LTH. Although such adaptations are critical to survival under conditions of the chronic stress, they may have “unintended consequences” from the standpoint of fetal programming of adipose tissue and HPA axis function. The challenge for the future will be to further elucidate the mechanisms responsible for this shift in phenotype induced by LTH. Understanding epigenetic changes in adipose tissue induced by LTH may lead to new treatment modalities to reverse the untoward effects on adipose tissue. Suppression of 11β-HSD1 in adipose tissue or selective treatment with FGF21 to enhance the expression of the metabolically active beige adipose tissue coupled with new imaging techniques like thermal imaging to assess adipose tissue function (162) will not only enhance our knowledge of the role of LTH on programming but also help to ameliorate long-term effects.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants PO1-HD-31226 and R01-HD-51951.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.A.N., D.A.M., and C.A.D. drafted manuscript; E.A.N., D.A.M., and C.A.D. edited and revised manuscript; E.A.N., D.A.M., and C.A.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.No authors listed. ACOG technical bulletin. Pulmonary disease in pregnancy. Number 224—June 1996. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 54: 187–196, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi K, Umezaki H, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia alters ovine fetal endocrine and physiological responses to hypotension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R209–R217, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MB, McMillen IC. Actions of hypoxia on catecholamine synthetic enzyme mRNA expression before and after development of adrenal innervation in the sheep fetus. J Physiol 529: 519–531, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams MB, Phillips ID, Simonetta G, McMillen IC. Differential effects of increasing gestational age and placental restriction on tyrosine hydroxylase, phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, and proenkephalin A mRNA levels in the fetal sheep adrenal. J Neurochem 71: 394–401, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahima RS, Saper CB, Flier JS, Elmquist JK. Leptin regulation of neuroendocrine systems. Front Neuroendocrinol 21: 263–307, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akagi K, Challis JR. Hormonal and biophysical responses to acute hypoxemia in fetal sheep at 0.7–0.8 gestation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 68: 1527–1532, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akagi K, Challis JR. Threshold of hormonal and biophysical responses to acute hypoxemia in fetal sheep at different gestational ages. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 68: 549–555, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andres RL, Day MC. Perinatal complications associated with maternal tobacco use. Semin Neonatol 5: 231–241, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker DJ. Adult consequences of fetal growth restriction. Clin Obstet Gynecol 49: 270–283, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 301: 1111, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker DJ. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 95: 115–128, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barker DJ. Obesity and early life. Obes Rev 8, Suppl 1: 45–49, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barker DJ, Bagby SP, Hanson MA. Mechanisms of disease: in utero programming in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 700–707, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker DJ, Clark PM. Fetal undernutrition and disease in later life. Rev Reprod 2: 105–112, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker DJ, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 341: 938–941, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D, Wadsworth ME. Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 298: 564–567, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 2: 577–580, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassett JM, Hanson C. Prevention of hypoinsulinemia modifies catecholamine effects in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R1171–R1181, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassett JM, Thorburn GD. Foetal plasma corticosteroids and the initiation of parturition in sheep. J Endocrinol 44: 285–286, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry LM, Polk DH, Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Padbury JF, Ervin MG. Preterm newborn lamb renal and cardiovascular responses after fetal or maternal antenatal betamethasone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R1972–R1979, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betito K, Diorio J, Meaney MJ, Boksa P. Adrenal phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase induction in relation to glucocorticoid receptor dynamics: evidence that acute exposure to high cortisol levels is sufficient to induce the enzyme. J Neurochem 58: 1853–1862, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhavina K, Radhika J, Pandian SS. VEGF and eNOS expression in umbilical cord from pregnancy complicated by hypertensive disorder with different severity. Biomed Res Int 2014: 982159, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bocking AD, McMillen IC, Harding R, Thorburn GD. Effect of reduced uterine blood flow on fetal and maternal cortisol. J Dev Physiol 8: 237–245, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boddy K, Jones CT, Mantell C, Ratcliffe JG, Robinson JS. Changes in plasma ACTH and corticosteroid of the maternal and fetal sheep during hypoxia. Endocrinology 94: 588–591, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bornstein SR, Uhlmann K, Haidan A, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Scherbaum WA. Evidence for a novel peripheral action of leptin as a metabolic signal to the adrenal gland: leptin inhibits cortisol release directly. Diabetes 46: 1235–1238, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boshier DP, Holloway H, Liggins GC. Effects of cortisol and ACTH on adrenocortical growth and cytodifferentiation in the hypophysectomized fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol 3: 355–373, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouloumie A, Schini-Kerth VB, Busse R. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates nitric oxide synthase expression in endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 41: 773–780, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyle DW, Meschia G, Wilkening RB. Metabolic adaptation of fetal hindlimb to severe, nonlethal hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 263: R1130–R1135, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle JW, Lotgering FK, Longo LD. Acute embolization of the uteroplacental circulation: uterine blood flow and placental CO diffusing capacity. J Dev Physiol 6: 377–386, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calkins K, Devaskar SU. Fetal origins of adult disease. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 41: 158–176, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev 84: 277–359, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carey LC, Su Y, Valego NK, Rose JC. Infusion of ACTH stimulates expression of adrenal ACTH receptor and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein mRNA in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E214–E220, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, Koch CJ, Ratcliffe P, Moons L, Jain RK, Collen D, Keshert E. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature 394: 485–490, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casteilla L, Forest C, Robelin J, Ricquier D, Lombet A, Ailhaud G. Characterization of mitochondrial-uncoupling protein in bovine fetus and newborn calf. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 252: E627–E636, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Challis JR, Brooks AN. Maturation and activation of hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal function in fetal sheep. Endocr Rev 10: 182–204, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Challis JR, Fraher L, Oosterhuis J, White SE, Bocking AD. Fetal and maternal endocrine responses to prolonged reductions in uterine blood flow in pregnant sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160: 926–932, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev 21: 514–550, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chrousos GP. The role of stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome: neuro-endocrine and target tissue-related causes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24, Suppl 2: S50–S55, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke L, Buss DS, Juniper DT, Lomax MA, Symonds ME. Adipose tissue development during early postnatal life in ewe-reared lambs. Exp Physiol 82: 1015–1027, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Kramer MS. Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 338: 147–152, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen WR, Piasecki GJ, Cohn HE, Susa JB, Jackson BT. Sympathoadrenal responses during hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hypoxemia in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 261: E95–E102, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohn HE, Sacks EJ, Heymann MA, Rudolph AM. Cardiovascular responses to hypoxemia and acidemia in fetal lambs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 120: 817–824, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Comline RS, Silver M. The release of adrenaline and noradrenaline from the adrenal glands of the foetal sheep. J Physiol 156: 424–444, 1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coulter CL, McMillen IC, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Placental restriction alters adrenal medullary development in the midgestation sheep fetus. Pediatr Res 44: 656–662, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curhan GC, Chertow GM, Willett WC, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ. Birth weight and adult hypertension and obesity in women. Circulation 94: 1310–1315, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Ascherio AL, Stampfer MJ. Birth weight and adult hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in US men. Circulation 94: 3246–3250, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devaskar SU, Anthony R, Hay W Jr. Ontogeny and insulin regulation of fetal ovine white adipose tissue leptin expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R431–R438, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ducsay CA. Fetal and maternal adaptations to chronic hypoxia: prevention of premature labor in response to chronic stress. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 119: 675–681, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ducsay CA, Furuta K, Vargas VE, Kaushal KM, Singleton K, Hyatt K, Myers DA. Leptin receptor antagonist treatment ameliorates the effects of long-term maternal hypoxia on adrenal expression of key steroidogenic genes in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R435–R442, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ducsay CA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Kaushal KM, Myers DA. Long-term hypoxia increases leptin receptors and plasma leptin concentrations in the late-gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1406–R1413, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ducsay CA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Root BK, Kaushal KM, Myers DA. Long-term hypoxia modulates expression of key genes regulating adrenomedullary function in the late gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1997–R2005, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ducsay CA, Newby EA, Cato C, Singleton K, Myers DA. Long term hypoxia during gestation alters perirenal adipose tissue in the lamb: a trigger for adiposity (Abstract)? J Dev Orig Health Dis 4: 1194, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dyer JL, McMillen IC, Warnes KE, Morrison JL. No evidence for an enhanced role of endothelial nitric oxide in the maintenance of arterial blood pressure in the IUGR sheep fetus. Placenta 30: 705–710, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.England LJ, Kendrick JS, Gargiullo PM, Zahniser SC, Hannon WH. Measures of maternal tobacco exposure and infant birth weight at term. Am J Epidemiol 153: 954–960, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, Fox EC, Mepani RJ, Verdeguer F, Wu J, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E, Spiegelman BM. FGF21 regulates PGC-1α and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev 26: 271–281, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fowden AL. The role of insulin in fetal growth. Early Hum Dev 29: 177–181, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fowden AL, Mundy L, Silver M. Developmental regulation of glucogenesis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. J Physiol 508: 937–947, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fraser M, Braems GA, Challis JR. Developmental regulation of corticotrophin receptor gene expression in the adrenal gland of the ovine fetus and newborn lamb: effects of hypoxia during late pregnancy. J Endocrinol 169: 1–10, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frias AE, Morgan TK, Evans AE, Rasanen J, Oh KY, Thornburg KL, Grove KL. Maternal high-fat diet disturbs uteroplacental hemodynamics and increases the frequency of stillbirth in a nonhuman primate model of excess nutrition. Endocrinology 152: 2456–2464, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fulton D, Fontana J, Sowa G, Gratton JP, Lin M, Li KX, Michell B, Kemp BE, Rodman D, Sessa WC. Localization of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylated on serine 1179 and nitric oxide in Golgi and plasma membrane defines the existence of two pools of active enzyme. J Biol Chem 277: 4277–4284, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gagnon R, Murotsuki J, Challis JR, Fraher L, Richardson BS. Fetal sheep endocrine responses to sustained hypoxemic stress after chronic fetal placental embolization. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 272: E817–E823, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gardner DS, Fletcher AJ, Bloomfield MR, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Effects of prevailing hypoxaemia, acidaemia or hypoglycaemia upon the cardiovascular, endocrine and metabolic responses to acute hypoxaemia in the ovine fetus. J Physiol 540: 351–366, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gardner DS, Fletcher AJ, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. A novel method for controlled and reversible long term compression of the umbilical cord in fetal sheep. J Physiol 535: 217–229, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gardner DS, Jamall E, Fletcher AJ, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Adrenocortical responsiveness is blunted in twin relative to singleton ovine fetuses. J Physiol 557: 1021–1032, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giussani DA, Phillips PS, Anstee S, Barker DJ. Effects of altitude versus economic status on birth weight and body shape at birth. Pediatr Res 49: 490–494, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gluckman PD. Editorial: nutrition, glucocorticoids, birth size, and adult disease. Endocrinology 142: 1689–1691, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gnanalingham MG, Mostyn A, Forhead AJ, Fowden AL, Symonds ME, Stephenson T. Increased uncoupling protein-2 mRNA abundance and glucocorticoid action in adipose tissue in the sheep fetus during late gestation is dependent on plasma cortisol and triiodothyronine. J Physiol 567: 283–292, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Godfrey KM, Barker DJ. Fetal nutrition and adult disease. Am J Clin Nutr 71: 1344s–1352s, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Godfrey KM, Barker DJ. Fetal programming and adult health. Public Health Nutr 4: 611–624, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Green LR, Kawagoe Y, Fraser M, Challis JR, Richardson BS. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis with repetitive umbilical cord occlusion in the preterm ovine fetus. J Soc Gynecol Investig 7: 224–232, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guerra C, Koza RA, Yamashita H, Walsh K, Kozak LP. Emergence of brown adipocytes in white fat in mice is under genetic control. Effects on body weight and adiposity. J Clin Invest 102: 412–420, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guy ES, Kirumaki A, Hanania NA. Acute asthma in pregnancy. Crit Care Clin 20: 731–745, x, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hameed A, Karaalp IS, Tummala PP, Wani OR, Canetti M, Akhter MW, Goodwin I, Zapadinsky N, Elkayam U. The effect of valvular heart disease on maternal and fetal outcome of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 893–899, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hanke CJ, Drewett JG, Myers CR, Campbell WB. Nitric oxide inhibits aldosterone synthesis by a guanylyl cyclase-independent effect. Endocrinology 139: 4053–4060, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harvey LM, Gilbert RD, Longo LD, Ducsay CA. Changes in ovine fetal adrenocortical responsiveness after long-term hypoxemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 264: E741–E747, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hennessy DP, Coghlan JP, Hardy KJ, Wintour EM. Development of the pituitary-adrenal axis in chronically cannulated ovine fetuses. J Dev Physiol 4: 339–352, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Himms-Hagen J, Cui J, Danforth E Jr, Taatjes DJ, Lang SS, Waters BL, Claus TH. Effect of CL-316,243, a thermogenic β3-agonist, on energy balance and brown and white adipose tissues in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R1371–R1382, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hollingworth SA, Deayton JM, Young IR, Thorburn GD. Prostaglandin E2 administered to fetal sheep increases the plasma concentration of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and the proportion of ACTH in low molecular weight forms. Endocrinology 136: 1233–1240, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Howe DC, Gertler A, Challis JR. The late gestation increase in circulating ACTH and cortisol in the fetal sheep is suppressed by intracerebroventricular infusion of recombinant ovine leptin. J Endocrinol 174: 259–266, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Imamura T, Umezaki H, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia alters endocrine and physiologic responses to umbilical cord occlusion in the ovine fetus. J Soc Gynecol Investig 11: 131–140, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ishibashi J, Seale P. Medicine. Beige can be slimming. Science 328: 1113–1114, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jackson BT, Cohn HE, Morrison SH, Baker RM, Piasecki GJ. Hypoxia-induced sympathetic inhibition of the fetal plasma insulin response to hyperglycemia. Diabetes 42: 1621–1625, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jackson BT, Morrison SH, Cohn HE, Piasecki GJ. Adrenal secretion of glucocorticoids during hypoxemia in fetal sheep. Endocrinology 125: 2751–2757, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jackson BT, Piasecki GJ, Cohn HE, Cohen WR. Control of fetal insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R2179–R2188, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jensen GM, Moore LG. The effect of high altitude and other risk factors on birthweight: independent or interactive effects? Am J Public Health 87: 1003–1007, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jequier E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Ann NY Acad Sci 967: 379–388, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jones CT, Boddy K, Robinson JS, Ratcliffe JG. Developmental changes in the responses of the adrenal glands of foetal sheep to endogenous adrenocorticotrophin, as indicated by hormone responses to hypoxaemia. J Endocrinol 72: 279–292, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jones CT, Ritchie JW, Walker D. The effects of hypoxia on glucose turnover in the fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol 5: 223–235, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kamitomo M, Longo LD, Gilbert RD. Right and left ventricular function in fetal sheep exposed to long-term high-altitude hypoxemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H399–H405, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kato A, Umezaki H, Imamura T, Kaushal KM, Mlynarczyk M, Gilbert RD, Bucholz J, Longo LD, Ducsay CA. Catecholamine and cardiovascular responses to superimposed hypoxia following carotid body denervation in the long-term hypoxemic ovine fetus (Abstract). J Soc Gynecol Investig 9: 186A, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keyes LE, Armaza JF, Niermeyer S, Vargas E, Young DA, Moore LG. Intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and intrauterine mortality at high altitude in Bolivia. Pediatr Res 54: 20–25, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kolas T, Nakling J, Salvesen KA. Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of preterm births among parous women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 79: 644–648, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kruse M, Bornstein SR, Uhlmann K, Paeth G, Scherbaum WA. Leptin down-regulates the steroid producing system in the adrenal. Endocr Res 24: 587–590, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumar R. Prenatal factors and the development of asthma. Curr Opin Pediatr 20: 682–687, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Le Roy C, Li JY, Stocco DM, Langlois D, Saez JM. Regulation by adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), angiotensin II, transforming growth factor-beta, and insulin-like growth factor I of bovine adrenal cell steroidogenic capacity and expression of ACTH receptor, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, cytochrome P450c17, and 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Endocrinology 141: 1599–1607, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lebrethon MC, Naville D, Begeot M, Saez JM. Regulation of corticotropin receptor number and messenger RNA in cultured human adrenocortical cells by corticotropin and angiotensin II. J Clin Invest 93: 1828–1833, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Leon DA, Koupilova I, Lithell HO, Berglund L, Mohsen R, Vagero D, Lithell UB, McKeigue PM. Failure to realise growth potential in utero and adult obesity in relation to blood pressure in 50 year old Swedish men. BMJ 312: 401–406, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Leos RA, Anderson MJ, Chen X, Pugmire J, Anderson KA, Limesand SW. Chronic exposure to elevated norepinephrine suppresses insulin secretion in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E770–E778, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liggins GC, Scroop GC, Haughey KG. Comparison of the effects of prostaglandin E2, prostacyclin and 1–24 adrenocorticotrophin on plasma cortisol levels of fetal sheep. J Endocrinol 95: 153–162, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay WW Jr. Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1716–E1725, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Linnemann K, Malek A, Sager R, Blum WF, Schneider H, Fusch C. Leptin production and release in the dually in vitro perfused human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4298–4301, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lolmede K, Durand de Saint Front V, Galitzky J, Lafontan M, Bouloumie A. Effects of hypoxia on the expression of proangiogenic factors in differentiated 3T3-F442A adipocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27: 1187–1195, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Louis TM, Challis JR, Robinson JS, Thorburn GD. Rapid increase of foetal corticosteroids after prostaglandin E2. Nature 264: 797–799, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lueder FL, Kim SB, Buroker CA, Bangalore SA, Ogata ES. Chronic maternal hypoxia retards fetal growth and increases glucose utilization of select fetal tissues in the rat. Metabolism 44: 532–537, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Magyar DM, Fridshal D, Elsner CW, Glatz T, Eliot J, Klein AH, Lowe KC, Buster JE, Nathanielsz PW. Time-trend analysis of plasma cortisol concentrations in the fetal sheep in relation to parturition. Endocrinology 107: 155–159, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matthews SG, Challis JR. Levels of pro-opiomelanocortin and prolactin mRNA in the fetal sheep pituitary following hypoxaemia and glucocorticoid treatment in late gestation. J Endocrinol 147: 139–146, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McMillen IC, Muhlhausler BS, Duffield JA, Yuen BS. Prenatal programming of postnatal obesity: fetal nutrition and the regulation of leptin synthesis and secretion before birth. Proc Nutr Soc 63: 405–412, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meaney MJ, Viau V, Bhatnagar S, Betito K, Iny LJ, O'Donnell D, Mitchell JB. Cellular mechanisms underlying the development and expression of individual differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress response. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 39: 265–274, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Monau TR, Vargas VE, King N, Yellon SM, Myers DA, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in the ovine fetal adrenal. Reprod Sci 16: 865–874, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Monau TR, Vargas VE, Zhang L, Myers DA, Ducsay CA. Nitric oxide inhibits ACTH-induced cortisol production in near-term, long-term hypoxic ovine fetal adrenocortical cells. Reprod Sci 17: 955–962, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moore VM, Miller AG, Boulton TJ, Cockington RA, Craig IH, Magarey AM, Robinson JS. Placental weight, birth measurements, and blood pressure at age 8 years. Arch Dis Child 74: 538–541, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mortola JP, Frappell PB, Aguero L, Armstrong K. Birth weight and altitude: a study in Peruvian communities. J Pediatr 136: 324–329, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mosier HD Jr, Dearden LC, Jansons RA, Roberts RC, Biggs CS. Disproportionate growth of organs and body weight following glucocorticoid treatment of the rat fetus. Dev Pharmacol Ther 4: 89–105, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mostyn A, Pearce S, Budge H, Elmes M, Forhead AJ, Fowden AL, Stephenson T, Symonds ME. Influence of cortisol on adipose tissue development in the fetal sheep during late gestation. J Endocrinol 176: 23–30, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Munck A, Guyre PM, Holbrook NJ. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev 5: 25–44, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Murotsuki J, Challis JR, Johnston L, Gagnon R. Increased fetal plasma prostaglandin E2 concentrations during fetal placental embolization in pregnant sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173: 30–35, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Myers DA, Bell P, Mlynarczyk M, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia alters plasma ACTH 1–39 and ACTH precursors in response to acute cord occlusion in the ovine fetus (Abstract). J Soc Gynecol Investig 11: 249A, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Myers DA, Bell PA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia enhances proopiomelanocortin processing in the near-term ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R1178–R1184, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Myers DA, Hanson K, Mlynarczyk M, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia modulates expression of key genes regulating adipose function in the late-gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1312–R1318, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Myers DA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Bird IM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia represses the expression of key genes regulating cortisol biosynthesis in the near-term ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1707–R1714, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Myers DA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Term hypoxia increases expression of transcription factors governing mitochondrial function and replication in peri-renal adipose tissue in the late gestation ovine fetus (Abstract). Reprod Sci 16: 331A, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ness RB, Sibai BM. Shared and disparate components of the pathophysiologies of fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195: 40–49, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Newby EA, Kaushal KM, Myers DA, Ducsay CA. Adrenocorticotropic Hormone and PI3K/Akt Inhibition Reduce eNOS Phosphorylation and Increase Cortisol Biosynthesis in Long-Term Hypoxic Ovine Fetal Adrenal Cortical Cells. Reprod Sci 22: 932–941, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nicol MR, Wang H, Ivell R, Morley SD, Walker SW, Mason JI. The expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in bovine adrenocortical cells. Endocr Res 24: 565–569, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nordentoft M, Lou HC, Hansen D, Nim J, Pryds O, Rubin P, Hemmingsen R. Intrauterine growth retardation and premature delivery: the influence of maternal smoking and psychosocial factors. Am J Public Health 86: 347–354, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Norman LJ, Lye SJ, Wlodek ME, Challis JR. Changes in pituitary responses to synthetic ovine corticotrophin releasing factor in fetal sheep. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 63: 1398–1403, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Novy MJ, Walsh SW. Dexamethasone and estradiol treatment in pregnant rhesus macaques: effects on gestational length, maternal plasma hormones, and fetal growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 145: 920–931, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ong KK, Dunger DB. Perinatal growth failure: the road to obesity, insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease in adults. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 16: 191–207, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ozolins IZ, Young IR, McMillen IC. Surgical disconnection of the hypothalamus from the fetal pituitary abolishes the corticotrophic response to intrauterine hypoglycemia or hypoxemia in the sheep during late gestation. Endocrinology 130: 2438–2445, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Padbury JF, Roberman B, Oddie TH, Hobel CJ, Fisher DA. Fetal catecholamine release in response to labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol 60: 607–611, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Papapetropoulos A, Garcia-Cardena G, Madri JA, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 100: 3131–3139, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Penhoat A, Jaillard C, Saez JM. Regulation of bovine adrenal cell corticotropin receptor mRNA levels by corticotropin (ACTH) and angiotensin-II (A-II). Mol Cell Endocrinol 103: R7–R10, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem 285: 7153–7164, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Phillips ID, Ross JT, Owens JA, Young IR, McMillen IC. The peptide ACTH(1–39), adrenal growth and steroidogenesis in the sheep fetus after disconnection of the hypothalamus and pituitary. J Physiol 491: 871–879, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Phillips ID, Simonetta G, Owens JA, Robinson JS, Clarke IJ, McMillen IC. Placental restriction alters the functional development of the pituitary-adrenal axis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. Pediatr Res 40: 861–866, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Piech-Dumas KM, Sterling CR, Tank AW. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression by muscarinic agonists in rat adrenal medulla. J Neurochem 73: 153–161, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Poissonnet CM, Burdi AR, Garn SM. The chronology of adipose tissue appearance and distribution in the human fetus. Early Hum Dev 10: 1–11, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Poore KR, Canny BJ, Young IR. Adrenal responsiveness and the timing of parturition in hypothalamo-pituitary disconnected ovine foetuses with and without constant adrenocorticotrophin infusion. J Neuroendocrinol 11: 343–349, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Pope M, Budge H, Symonds ME. The developmental transition of ovine adipose tissue through early life. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 210: 20–30, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Poulos SP, Hausman DB, Hausman GJ. The development and endocrine functions of adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol 323: 20–34, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Reinisch JM, Simon NG, Karow WG, Gandelman R. Prenatal exposure to prednisone in humans and animals retards intrauterine growth. Science 202: 436–438, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Risinger GM Jr, Hunt TS, Updike DL, Bullen EC, Howard EW. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression by vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated by both stimulatory and inhibitory signals in response to growth factors. J Biol Chem 281: 25915–25925, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Robinson JS, Kingston EJ, Jones CT, Thorburn GD. Studies on experimental growth retardation in sheep. The effect of removal of a endometrial caruncles on fetal size and metabolism. J Dev Physiol 1: 379–398, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Robinson JS, Moore VM, Owens JA, McMillen IC. Origins of fetal growth restriction. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 92: 13–19, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Robinson JS, Owens JA, Owens PC. Fetal growth and fetal growth retardation. In: Textbook of Fetal Physiology, edited by Thorburn GD, Harding R. Oxford, UK: Oxford University, 1994, p. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Rose JC, Meis PJ, Urban RR, Greiss FC Jr. In vivo evidence for increased adrenal sensitivity to adrenocorticotropin-(1–24) in the lamb fetus late in gestation. Endocrinology 111: 80–85, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JH, Ravelli AC, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Bleker OP. Effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on adult disease in later life: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol 185: 93–98, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rosmond R. Role of stress in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30: 1–10, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Rurak DW. Plasma vasopressin levels during hypoxaemia and the cardiovascular effects of exogenous vasopressin in foetal and adult sheep. J Physiol 277: 341–357, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Salafia CM, Vogel CA, Bantham KF, Vintzileos AM, Pezzullo J, Silberman L. Preterm delivery: correlations of fetal growth and placental pathology. Am J Perinatol 9: 190–193, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, Scime A, Devarakonda S, Conroe HM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Rudnicki MA, Beier DR, Spiegelman BM. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454: 961–967, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Seale P, Conroe HM, Estall J, Kajimura S, Frontini A, Ishibashi J, Cohen P, Cinti S, Spiegelman BM. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 96–105, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Seckl JR. Glucocorticoid programming of the fetus; adult phenotypes and molecular mechanisms. Mol Cell Endocrinol 185: 61–71, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Seckl JR. Glucocorticoids and small babies. Q J Med 87: 259–262, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Sewer MB, Waterman MR. CAMP-dependent protein kinase enhances CYP17 transcription via MKP-1 activation in H295R human adrenocortical cells. J Biol Chem 278: 8106–8111, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Shen BQ, Lee DY, Zioncheck TF. Vascular endothelial growth factor governs endothelial nitric-oxide synthase expression via a KDR/Flk-1 receptor and a protein kinase C signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 274: 33057–33063, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Simmonds PJ, Phillips ID, Poore KR, Coghill ID, Young IR, Canny BJ. The role of the pituitary gland and ACTH in the regulation of mRNAs encoding proteins essential for adrenal steroidogenesis in the late-gestation ovine fetus. J Endocrinol 168: 475–485, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Sperling MA, Christensen RA, Ganguli S, Anand R. Adrenergic modulation of pancreatic hormone secretion in utero: studies in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 14: 203–208, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Stachowiak MK, Goc A, Hong JS, Poisner A, Jiang HK, Stachowiak EK. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in depolarized non-transformed bovine adrenal medullary cells: second messenger systems and promoter mechanisms. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 22: 309–319, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Su Y, Carey LC, Rose JC, Pulgar VM. Leptin alters adrenal responsiveness by decreasing expression of ACTH-R, StAR, and P450c21 in hypoxemic fetal sheep. Reprod Sci 19: 1075–1084, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Sug-Tang A, Bocking AD, Brooks AN, Hooper S, White SE, Jacobs RA, Fraher LJ, Challis JR. Effects of restricting uteroplacental blood flow on concentrations of corticotrophin-releasing hormone, adrenocorticotrophin, cortisol, and prostaglandin E2 in the sheep fetus during late pregnancy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 70: 1396–1402, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Symonds ME, Budge H. How promising is thermal imaging in the quest to combat obesity? Imag Med 4: 589–591, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Symonds ME, Budge H, Perkins AC, Lomax MA. Adipose tissue development—impact of the early life environment. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 106: 300–306, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Symonds ME, Mostyn A, Pearce S, Budge H, Stephenson T. Endocrine and nutritional regulation of fetal adipose tissue development. J Endocrinol 179: 293–299, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Symonds ME, Stephenson T. Maternal nutrition and endocrine programming of fetal adipose tissue development. Biochem Soc Trans 27: 97–103, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Tai TC, Claycomb R, Her S, Bloom AK, Wong DL. Glucocorticoid responsiveness of the rat phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase gene. Mol Pharmacol 61: 1385–1392, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Thorburn GD. The placenta, PGE2 and parturition. Early Hum Dev 29: 63–73, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Thorburn GD, Hollingworth SA, Hooper SB. The trigger for parturition in sheep: fetal hypothalamus or placenta? J Dev Physiol 15: 71–79, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J Psychosom Res 53: 865–871, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Tsubaki M, Hiwatashi A, Ichikawa Y, Hori H. Electron paramagnetic resonance study of ferrous cytochrome P-450scc-nitric oxide complexes: effects of cholesterol and its analogues. Biochemistry 26: 4527–4534, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Tsubaki M, Ichikawa Y, Fujimoto Y, Yu NT, Hori H. Active site of bovine adrenocortical cytochrome P-450(11) beta studied by resonance Raman and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopies: distinction from cytochrome P-450scc. Biochemistry 29: 8805–8812, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Unno N, Giussani DA, Hing WK, Ding XY, Collins JH, Nathanielsz PW. Changes in adrenocorticotropin and cortisol responsiveness after repeated partial umbilical cord occlusions in the late gestation ovine fetus. Endocrinology 138: 259–263, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]