Abstract

1,3-Enynes containing allylic hydrogens cis to the alkyne function as three-carbon components in rhodium(III)-catalyzed, all-carbon [3+3] oxidative annulations to produce spirodialins. The proposed mechanism of these reactions involves the alkenyl-to-allyl 1,4-rhodium(III) migration.

Keywords: allylation, C–H activation, enynes, homogeneous catalysis, rhodium

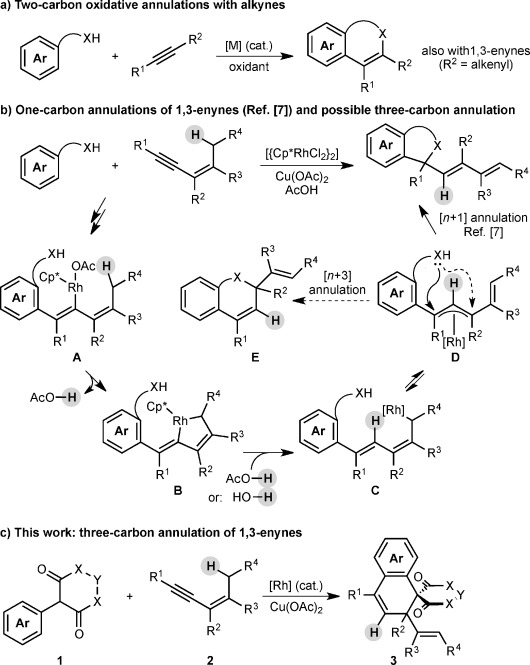

Transition metal-catalyzed oxidative annulations of alkynes[1] that proceed by directing group-promoted C(sp2)–H functionalization[1, 2] are versatile methods for heterocycle[3] and carbocycle[4] synthesis. Alkynes, including 1,3-enynes,[5] serve as two-carbon components in these reactions (Scheme 1 a). However, analogous reactions that result in three-carbon annulation are currently underdeveloped,[6] and addressing this shortcoming would expand the range of products accessible using C–H functionalization/oxidative annulation chemistry.

Scheme 1.

Catalytic oxidative annulations of alkynes and 1,3-enynes.

Using rhodium(III) catalysis, we recently discovered a new mode of oxidative annulation of 1,3-enynes that contain allylic hydrogens cis to the alkyne, in which they act as one-carbon components (Scheme 1 b).[7] The proposed mechanism[7] involves the 1,4-rhodium(III) migration[8, 9] of alkenylrhodium species A to give σ-allylrhodium(III) species C via rhodacycle B. Following isomerization of C into the electrophilic π-allylrhodium(III) species D, nucleophilic trapping by the directing group gives the product of [n+1] annulation. Given the isomerization of C into D, there exists the possibility for cyclization to occur at a different position of the extended π-system to give E, a product of [n+3] annulation (Scheme 1 b).[6]

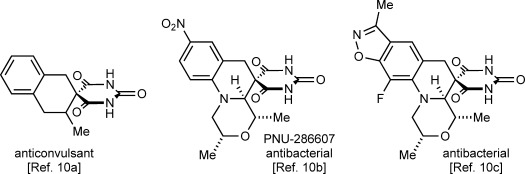

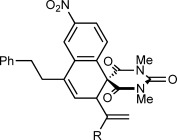

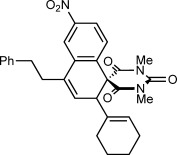

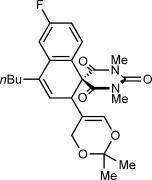

Herein, we describe the realization of this possibility in rhodium(III)-catalyzed reactions of 2-aryl cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyls 1 with 1,3-enynes 2 to give spirodialins 3 (Scheme 1 c). The majority of the products obtained are spirocyclic barbiturates, which are of interest given the well-established medicinal importance of the barbiturate motif, and the biological activity of structurally related spirocycles (Figure 1).[10]

Figure 1.

Biologically active spirocyclic barbiturates.

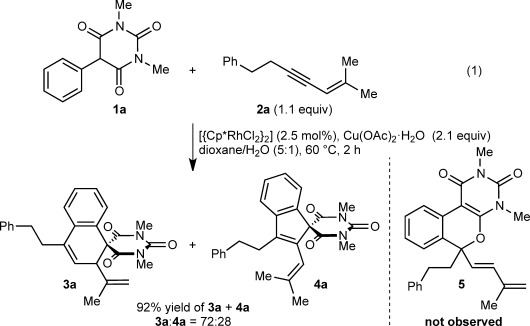

During our studies of metal-catalyzed oxidative annulations of alkynes,[4a,b,e, 7] the reaction of 5-arylbarbituric acid 1 a with 1,3-enyne 2 a was performed using [{Cp*RhCl2}2] (2.5 mol %) and Cu(OAc)2⋅H2O (2.1 equiv) in dioxane/H2O (5:1) at 60 °C [Eq. (1)]. As well as providing the spiroindene 4 a through a standard two-carbon annulation,[4a,b,e] a [3+3] annulation occurred to give spirodialin 3 a as the major product. No one-carbon annulation product 5[7] was detected. Chromatographic purification gave a 72:28 mixture of 3 a and 4 a in 92 % yield. Without H2O, more side products were formed and the ratio of 3 a:4 a decreased to ca. 50:50. No reaction occurred without Cu(OAc)2⋅H2O.[11]

|

(1) |

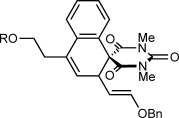

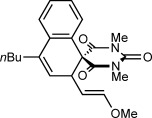

Further studies revealed the benzyloxy-containing 1,3-enyne 2 b to be superior to 2 a; the reaction of 2 b with 1 a gave spirodialin 3 b only, in 88 % yield as the E-isomer (Scheme 2). Reaction of 2 b with various 5-arylbarbituric acids[12] demonstrated compatibility with nitro (3 c), acetoxy (3 d), and halogen substituents (3 f–3 h) on the aryl group.[13] Spirodialin 3 e was not formed under the standard conditions,[14] but replacing dioxane/H2O with undried DMF enabled productive [3+3] annulation and isolation of 3 e in 37 % yield, along with several side products.[14] Free N–H groups on the barbituric acids were also tolerated (3 i and 3 j). In the latter case, 3 j was formed as a 1:1 inseparable mixture of diastereomers. The reaction of 2-phenyl Meldrum’s acid also gave [3+3] annulation, but the yield of 6 was only 32 % due to decomposition of the starting material and product under the acidic conditions.[15] Decreasing the loading of [{Cp*RhCl2}2] to 0.5 mol % in the reaction of 1 a with 2 b was well-tolerated and provided 3 b in 77 % yield.

Scheme 2.

[a] Conducted with 0.50 mmol of 1 a–1 j. [b] Yield of isolated products. [b] Conducted with 0.5 mol % of [{Cp*RhCl2}2]. [c] Conducted in undried DMF. Side products were also obtained; see Ref. [14]. [d] Conducted at 120 °C. [e] Conducted with 5 mol % of [{Cp*RhCl2}2].

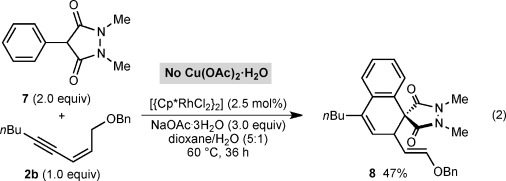

Interestingly, Cu(OAc)2⋅H2O rapidly decomposed cyclic hydrazide 7, precluding its use as the oxidant in the reaction with 1,3-enyne 2 b [Eq. (2)]. However, reaction of 7 (2.0 equiv) with 2 b without Cu(OAc)2⋅H2O but with inclusion of NaOAc⋅3H2O (3.0 equiv) gave spirodialin 8 in 47 % yield, along with 2 b (30 % recovery). We speculate that the N–N bond of 7 could be serving as an oxidant to regenerate the catalyst,[16] but we were unable to isolate the reduced form of 7 to confirm this hypothesis.

|

(2) |

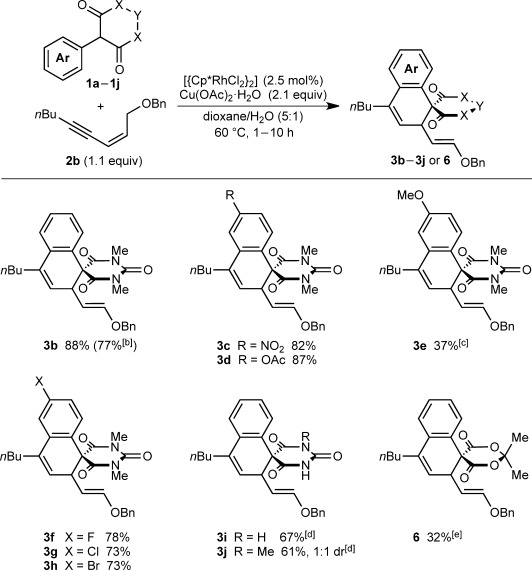

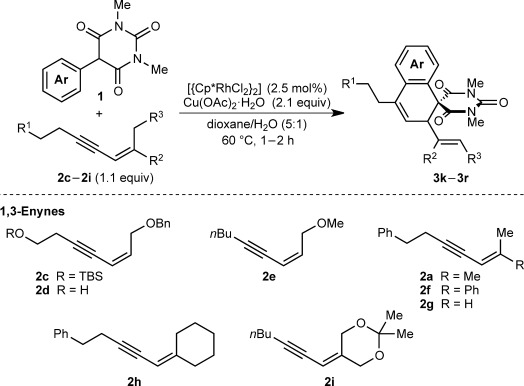

Table 1 presents the results of oxidative annulations of 5-arylbarbituric acids with various 1,3-enynes. No spiroindenes or benzopyrans from two- or one-carbon annulations, respectively, were detected. 1,3-Enynes 2 c and 2 d, containing protected or unprotected 2-hydroxyethyl groups on the alkyne were tolerated (entries 1 and 2). Use of a methoxy group in the 1,3-enyne in place of a benzyloxy group was also possible (entry 3). With a 5-(4-nitrophenyl)-substituted barbituric acid, oxidative annulations with 1,3-enynes 2 a, 2 f, and 2 g containing various groups trans to the alkyne proceeded efficiently to give spirodialins 3 n–3 p in 72–95 % yield (entries 4–6). As with the corresponding one-carbon annulations,[7] the 4-nitrophenyl group favors 1,4-rhodium(III) migration over the formation of spiroindenes [compare with Eq. (1)]. 1,3-Enynes 2 h and 2 i containing cyclic groups were also competent substrates (entries 7 and 8), and spirodialin 3 r was isolated in 57 % yield, despite containing a potentially acid-sensitive enol acetal.

Table 1.

[3+3] Oxidative annulations of various 1,3-enynes[a]

| Entry | 1,3-Enyne | Product | Yield [%][b] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 2 | 2 c 2 d |  |

3 k R=TBS 3 l R=H | 60 64 |

| 3 | 2 e |  |

3 m | 80 |

| 4 5 6 | 2 a 2 f 2 g |  |

3 n R=Me 3 o R=Ph 3 p R=H | 95 78 72 |

| 7 | 2 h |  |

3 q | 86 |

| 8 | 2 i |  |

3 r | 57 |

[a] Conducted with 0.50 mmol of 1. [b] Yield of isolated products.

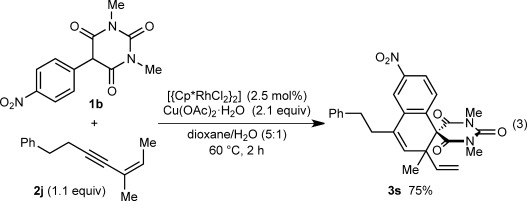

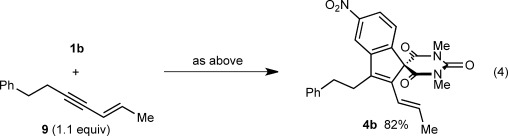

Notably, the formation of a highly sterically hindered spirodialin 3 s containing contiguous all-carbon sp3 quaternary centers from 1,3-enyne 2 j occurred efficiently [Eq. (3)]. The reaction of 1 b with 1,3-enyne 9, which does not contain any cis-allylic hydrogens, led only to the formation of spiroindene 4 b in 82 % yield, thus highlighting the importance of this structural feature for [3+3] annulation [Eq. (4)].

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

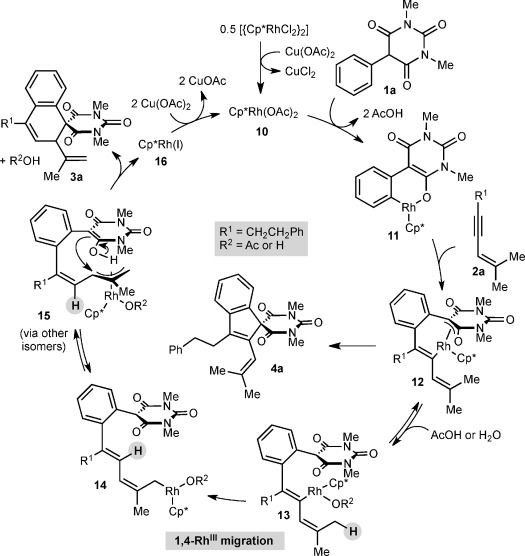

Scheme 3 depicts a possible catalytic cycle for these reactions, using representative substrates 1 a and 2 a. This cycle is similar to that proposed for the one-carbon annulations we described previously.[7] Cyclorhodation of 1 a with rhodium diacetate 10 would give rhodacycle 11. Migratory insertion of 1,3-enyne 2 a then provides rhodacycle 12, which upon reductive elimination would give spiroindene 4 a. However, reversible protonolysis of 12 forms alkenyrhodium species 13, which can then undergo 1,4-rhodium(III) migration to form σ-allylrhodium(III) species 14. This intermediate can lead to π-allylrhodium(III) species 15 by a series of σ–π–σ interconversions and E/Z isomerization. Outer sphere nucleophilic attack of the π-allylrhodium(III) moiety[17, 18] of 15 by C5 of the barbituric acid then gives spirodialin 3 a and rhodium(I) species 16, which undergoes Cu(OAc)2-promoted oxidation to regenerate 10. The preference of 5-monosubstituted barbituric acids for C-allylation over O-allylation has been observed previously in Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylations.[19] However, an alternative pathway involving an inner-sphere reductive elimination cannot be excluded.

Scheme 3.

Possible catalytic cycle.

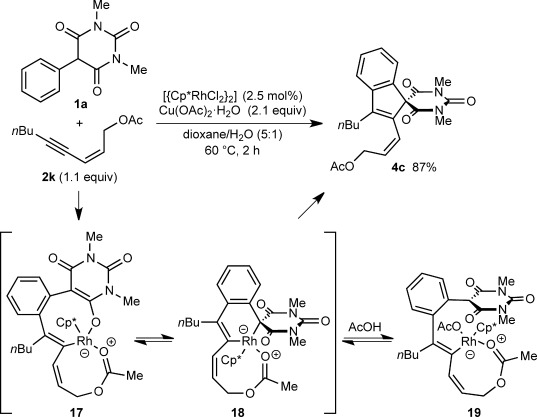

The reaction of 1 a with 1,3-enyne 2 k gave spiroindene 4 c only (Scheme 4), a result that differs from the formation of spirodialins 3 b (Scheme 2) and 3 m (Table 1, entry 3) from 1,3-enynes 2 b and 2 e, respectively. A possible explanation for this contrasting behavior might be coordination of the acetoxy group to rhodium, resulting in stabilization of 18-electron intermediates such as rhodacycles 17 and 18 (analogous to 12 in Scheme 3, but the σ-haptomers) or alkenylrhodium species 19. This stabilization likely disfavors 1,4-rhodium(III) migration and leads instead to reductive elimination from 18 to give 4 c.

Scheme 4.

Formation of spiroindene 4 c from 1,3-enyne 2 k.

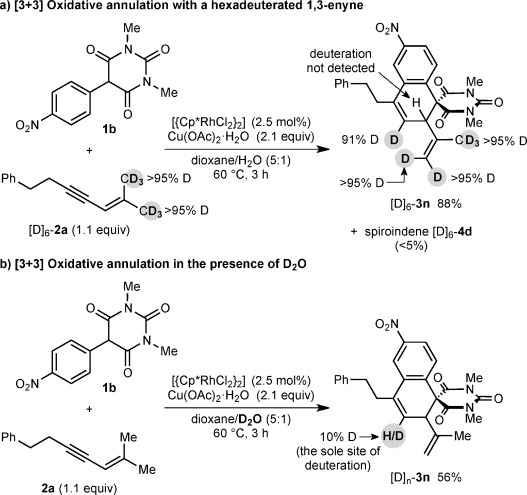

The reaction of 1 b with the hexadeuterated 1,3-enyne [D]6-2 a gave traces of a spiroindene [D]6-4 d (<5 %), and spirodialin [D]6-3 n in 88 % yield (Scheme 5 a), in which incomplete deuterium transfer (91 % D) from the cis-allylic position of [D]6-2 a to the alkenyl position of the dialin ring of [D]6-3 n was observed. Furthermore, the reaction of 1 b with 2 a in 5:1 dioxane/D2O led to 10 % deuteration at the same position of [D]n-3 n, with no spiroindene detected (Scheme 5 b). These results are similar to the corresponding experiments with [D]6-2 a in the one-carbon annulations reported previously,[7] and are consistent with 1,4-rhodium(III) migration occurring by a concerted metalation-deprotonation/reprotonation sequence (similar to A to C in Scheme 1 b).[7]

Scheme 5.

Oxidative annulation with a hexadeuterated 1,3-enyne.

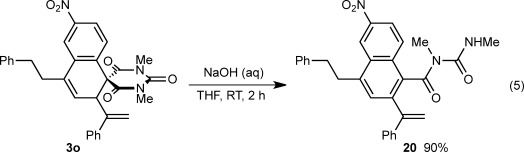

Although the spirocyclic barbiturates prepared in this study are themselves of interest, they can be transformed into other compounds. For example, treatment of 3 o with aqueous NaOH in THF gave the highly functionalized naphthalene 20 in 90 % yield [Eq. (5)].

|

(5) |

In conclusion, we have reported rhodium(III)-catalyzed, all-carbon [3+3] oxidative annulations of 5-arylbarbituric acids and related compounds with 1,3-enynes containing allylic hydrogens cis to the alkyne. This new mode of oxidative annulation further demonstrates the power of alkenyl-to-allyl 1,4-rhodium(III) migration in generating electrophilic allylrhodium species for the construction of polycyclic systems. Other applications of this method of allylmetal generation will be reported in due course.

Supporting Information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

miscellaneous_information

References

- 1a.Satoh T, Miura M. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:11212–11222. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b.Ackermann L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:281–295. doi: 10.1021/ar3002798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Shi G, Zhang Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:1419–1442. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201301033. For selected reviews, see. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b.Kuhl N, Schröder N, Glorius F. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:1443–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 2c.De Sarkar S, Liu W, Kozhushkov SI, Ackermann L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:1461–1479. [Google Scholar]

- 2d.Engle KM, Yu J-Q. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:8927–8955. doi: 10.1021/jo400159y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2e.Engle KM, Mei T-S, Wasa M, Yu J-Q. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:788–802. doi: 10.1021/ar200185g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2f.Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215–1292. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2g.Wencel-Delord J, Droege T, Liu F, Glorius F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4740–4761. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15083a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2h.Ackermann L. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1315–1345. doi: 10.1021/cr100412j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Seoane A, Casanova N, Quiñones N, Mascareñas JL, Gulías M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:834–837. doi: 10.1021/ja410538w. For recent, selected examples of metal-catalyzed oxidative annulations of alkynes that result in heterocycles, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b.Kornhaaß C, Kuper C, Ackermann L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:1619–1624. [Google Scholar]

- 3c.Peng X, Wang W, Jiang C, Sun D, Xu Z, Tung C-H. Org. Lett. 2014;16:5354–5357. doi: 10.1021/ol5025426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d.Jayakumar J, Parthasarathy K, Chen Y-H, Lee T-H, Chuang S-C, Cheng C-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9889–9892. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126:10047–10050. [Google Scholar]

- 3e.Zhang X, Si W, Bao M, Asao N, Yamamoto Y, Jin T. Org. Lett. 2014;16:4830–4833. doi: 10.1021/ol502317c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f.Peng X, Wang W, Jiang C, Sun D, Xu Z, Tung C-H. Org. Lett. 2014;16:5354–5357. doi: 10.1021/ol5025426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3g.Li J, John M, Ackermann L. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:5403–5408. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3h.Jayakumar J, Parthasarathy K, Chen Y-H, Lee T-H, Chuang S-C, Cheng C-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9889–9892. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126:10047–10050. [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Reddy Chidipudi S, Khan I, Lam HW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12115–12119. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207170. For recent, selected examples of metal-catalyzed oxidative annulations of alkynes that result in carbocycles, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2012;124:12281–12285. [Google Scholar]

- 4b.Dooley JD, Reddy Chidipudi S, Lam HW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10829–10836. doi: 10.1021/ja404867k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c.Nan J, Zuo Z, Luo L, Bai L, Zheng H, Yuan Y, Liu J, Luan X, Wang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17306–17309. doi: 10.1021/ja410060e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d.Pham MV, Cramer N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3484–3487. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126:3552–3555. [Google Scholar]

- 4e.Kujawa S, Best D, Burns DJ, Lam HW. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:8599–8602. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f.Seoane A, Casanova N, Quiñones N, Mascareñas JL, Gulías M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7607–7610. doi: 10.1021/ja5034952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4g.Zhou M-B, Pi R, Hu M, Yang Y, Song R-J, Xia Y, Li J-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:11338–11341. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126:11520–11523. [Google Scholar]

- 4h.Jia J, Shi J, Zhou J, Liu X, Song Y, Xu HE, Yi W. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:2925–2928. doi: 10.1039/c4cc09823d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4i.Zheng J, Wang S-B, Zheng C, You S-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4880–4883. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Huestis MP, Chan L, Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1338–1341. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2011;123:1374–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 5b.Ackermann L, Lygin AV, Hofmann N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6379–6382. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2011;123:6503–6506. [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Shi Z, Grohmann C, Glorius F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:5393–5397. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301426. For three-carbon annulations in catalytic C–H functionalizations, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125:5503–5507. [Google Scholar]

- 6b.Cui S, Zhang Y, Wu Q. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3421–3426. [Google Scholar]

- 6c.Cui S, Zhang Y, Wang D, Wu Q. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3912–3916. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns DJ, Lam HW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9931–9935. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126:10089–10093. [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Ikeda Y, Takano K, Kodama S, Ishii Y. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:11104–11106. doi: 10.1039/c3cc46700g. For stoichiometric 1,4-rhodium(III) migration, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Ikeda Y, Takano K, Waragai M, Kodama S, Tsuchida N, Takano K, Ishii Y. Organometallics. 2014;33:2142–2145. [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Ma S, Gu Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7512–7517. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501298. For reviews of 1,4-metal migration, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2005;117:7680–7685. [Google Scholar]

- 9b.Shi F, Larock RC. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010;292:123–164. doi: 10.1007/128_2008_46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.King SB, Stratford ES, Craig CR, Fifer EK. Pharm. Res. 1995;12:1240–1243. doi: 10.1023/a:1016236615559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b.Miller AA, Bundy GL, Mott JE, Skepner JE, Boyle TP, Harris DW, Hromockyj AE, Marotti KR, Zurenko GE, Munzner JB, Sweeney MT, Bammert GF, Hamel JC, Ford CW, Zhong W-Z, Graber DR, Martin GE, Han F, Dolak LA, Seest EP, Ruble JC, Kamilar GM, Palmer JR, Banitt LS, Hurd AR, Barbachyn MR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2806–2812. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00247-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c.Basarab GS, Brassil P, Doig P, Galullo V, Haimes HB, Kern G, Kutschke A, McNulty J, Schuck VJA, Stone G, Gowravaram M. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:9078–9095. doi: 10.1021/jm501174m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Lu Y, Wang H-W, Spangler JE, Chen K, Cui P-P, Zhao Y, Sun W-Y, Yu J-Q. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:1923–1927. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03350g. Reactions conducted in the absence of Cu(OAc)2⋅H2O under an oxygen atmosphere in the presence of sodium carboxylates were unsuccessful. See. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b.Warratz S, Kornhaaß C, Cajaraville A, Niepötter B, Stalke D, Ackermann L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:5513–5517. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2015;127:5604–5608. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best D, Burns DJ, Lam HW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;127:7518–7521. Many of the 5-arylbarbituric acids were prepared by the rhodium(II)-catalyzed direct arylation of 5-diazobarbituric acids, see. [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2015;54:7410–7413. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The structure of 3 h was confirmed by X-ray crystallography. CCDC 1057433 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

- 14. Under the standard conditions, an oxidative dimer of 5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-dimethylbarbituric acid was the sole product. In 5:1 DMF/H2O, spirodialin 3 e was accompanied by this oxidative dimer and the spiroindene resulting from two-carbon annulation. See the Supporting Information for further details.

- 15. Basic additives such as K2CO3 (see Ref. [4a]) were detrimental.

- 16a.Zhao D, Shi Z, Glorius F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:12426–12429. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306098. For examples of N–N-containing groups as internal oxidants in C–H functionalizations, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125:12652–12656. [Google Scholar]

- 16b.Wang C, Huang Y. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5294–5297. doi: 10.1021/ol402523x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16c.Liu B, Song C, Sun C, Zhou S, Zhu J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16625–16631. doi: 10.1021/ja408541c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16d.Cui S, Zhang Y, Wang D, Wu Q. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3912–3916. [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Lautens M, Fagnou K, Hiebert S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;36:48–58. doi: 10.1021/ar010112a. For reviews covering rhodium-catalyzed allylic substitutions, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b.Evans PA. Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Tsui GC, Lautens M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5400–5404. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200390. For recent examples of rhodium-catalyzed allylic substitutions, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2012;124:5496–5500. [Google Scholar]

- 18b.Zhu J, Tsui GC, Lautens M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12353–12356. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2012;124:12519–12522. [Google Scholar]

- 18c.Arnold JS, Nguyen HM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8380–8383. doi: 10.1021/ja302223p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18d.Evans PA, Clizbe EA, Lawler MJ, Oliver S. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1835–1838. [Google Scholar]

- 18e.Evans PA, Oliver S, Chae J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19314–19317. doi: 10.1021/ja306602g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18f.Evans PA, Oliver S. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5626–5629. doi: 10.1021/ol402336u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18g.Arnold JS, Mwenda ET, Nguyen HM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3688–3692. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126:3762–3766. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trost BM, Schroeder GM. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:1569–1573. doi: 10.1021/jo991491c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

miscellaneous_information