Abstract

A 60-year-old woman with a history of recurrent headaches and blurred vision but otherwise healthy presented to an ophthalmologist with bilateral optic disc edema. Intravenous methylprednisonlone was administered because of a concern for optic neuritis. The patient’s vision declined to hand motions level in both eyes and a subsequent evaluation revealed bilateral acute retinal necrosis with bilateral central retinal artery occlusions. Aqueous humor polymerase chain reaction analysis was positive for herpes simplex virus (HSV), establishing a diagnosis of HSV-associated bilateral acute retinal necrosis (ARN) and meningitis. Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) has rarely been reported in association with ARN and the particularly fulminant course with bilateral CRAO in association with ARN has not been previously reported. Our patient’s disease course emphasizes the importance of careful peripheral examination in patients with presumptive optic neuritis, judicious use of systemic corticosteroid in this context, and the retinal vaso-obliterative findings that may be observed in the pathogenesis of ARN.

Introduction

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN), also known as Kirisawa uveitis1, is an infectious retinitis caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV) or herpes simplex virus (HSV), type 1 or 2. Risk factors for this disease include immunosuppression or previous ocular, meningeal or encephalitic infection.2 Retinal vascular occlusion is one of the criterion in the diagnosis of ARN,3 and is most often peripheral in location, although central retinal vascular occlusion may rarely be observed.4 We describe herein a case of bilateral acute retinal necrosis (BARN) with bilateral central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) causing severe vision loss in a 60 year-old woman without evidence of immunosuppression who presented with bilateral optic disc edema and headaches, which were consistent with HSV meningitis.

Case Report

A 60 year-old woman with a history of hypertension and migraine headaches was referred to our institution with dull, throbbing bifrontal headaches of one-month duration and severe vision loss in both eyes.

Three days after the initial onset of headaches, the patient presented to an outside emergency department, where a non-contrast CT of the head was unremarkable. Because of worsening headaches, nausea, and vomiting, she returned to the emergency department twice over the ensuing two weeks. A repeat head CT was unremarkable, and the patient was treated symptomatically with analgesics.

Three weeks after the onset of her headache, she developed blurred vision in both eyes. Visual acuities (VA) were 20/50 in the right eye (OD) and 20/40 in the left eye (OS). Funduscopic examination showed mild optic disc edema in both eyes. A Humphrey visual field test 24-2 showed a superior arcuate defect OD and an enlarged blind spot OS. An MRI of the brain and orbits showed hyperintense foci in the white matter regions on T2 and FLAIR imaging. The patient was then referred to a neurologist who was concerned for optic neuritis, prompting administration of three pulse 1-gram doses of intravenous methylprednisolone. The patient’s headaches and visual loss did not improve, and she returned to the emergency department after completing the corticosteroid infusions. A lumbar puncture showed an opening pressure of 19 cm H2O, protein 54 mg/dl (Reference 15–45 mg/dl), glucose 48 mg/ml (50–75 mg/dl), and an elevated white blood cell count of 116 cells/ul with 100% lymphocytes. The Gram stain and culture were negative. She was diagnosed with aseptic meningitis and symptomatic therapy was recommended. Over the next three days, her vision rapidly declined, prompting an urgent referral to our institution.

On presentation, the patient’s visual acuities were hand motions OD and light perception only OS. Her pupils were both 8 mm and minimally reactive OU. Intraocular pressures were 19 mmHg OU. Slit lamp examination showed 2+ conjunctival injection, keratic precipitates, 2+ anterior chamber cell and 2+ anterior vitreous cell OU. Funduscopic examination showed pale-appearing optic nerves with obliteration of the retinal arteries (Figures 1 and 2). There was diffuse macular whitening, 360 degrees of confluent retinal whitening in the periphery, and yellow-appearing, subretinal exudation with low-lying inferior retinal detachments OU. On fluorescein angiography, there was minimal choroidal filling as well as extremely delayed retinal arterial perfusion. There was also marked optic disk leakage OU (Figures 1 and 2).

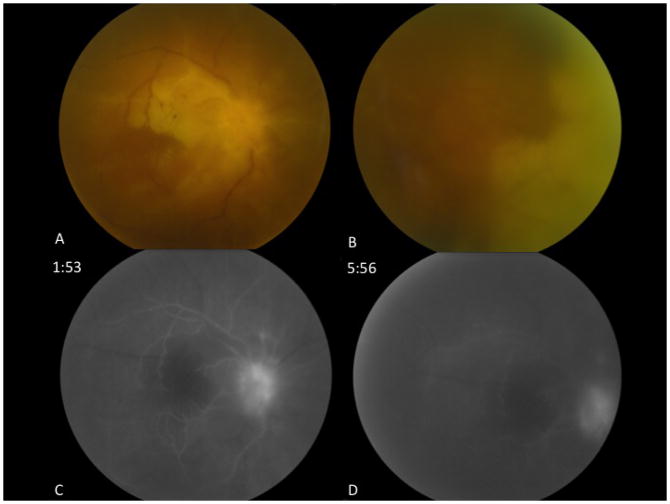

Figure 1.

Fundus photographs and fluorescein angiogram of the right eye. Fundus photograph of the posterior pole of the right eye shows a pale optic nerve, sclerotic retinal vessels and retinal whitening involving the macula (A). Confluent retinal whitening with obliteration of the vessels is observed nasally (B). Fluorescein angiogram of the right eye shows extremely delayed retinal arterial filling at 1:53 (C) with incomplete filling at 5:56 and late leakage of the optic disc (D).

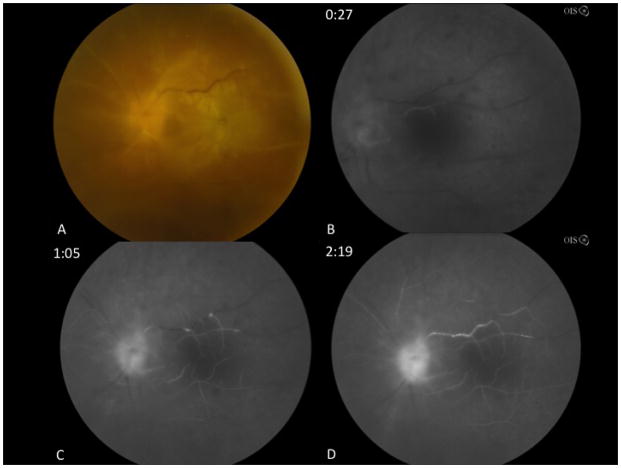

Figure 2.

Fundus photographs and fluorescein angiogram of the left eye. Fundus photograph of the posterior pole of the left eye shows similar findings compared to the right eye with optic nerve pallor, retinal vascular obliteration, and pale-appearing macula with retinal whitening (A). Fluorescein angiography shows poor choroidal and central retinal artery filling at 27 seconds (B). Incomplete filling of arterial tree is observed at 1:05 (C). Fluorescein angiogram at 2:19 shows incomplete retinal arterial filling and optic disc leakage (D).

The patient was diagnosed with presumed bilateral acute retinal necrosis (BARN). Bilateral diagnostic anterior chamber paracenteses and injections of ganciclovir (2 mg/0.1 cc) and foscarnet (2.4 mg/0.1 cc) were performed. Aqueous polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for varicella zoster virus (VZV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and toxoplasmosis were sent. Serologies for HSV-1 and HSV-2 were also sent. She was admitted to our hospital and started on intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg/kg every 12 hours). Serologic testing including HIV ELISA, RPR, syphilis IgG, quantiferon-TB-Gold, and toxoplasmosis IgG and IgM were negative. A repeat MRI of the brain showed scattered hyperintense foci on the T2 and FLAIR sequences, which were similar in appearance to the prior MRI. Aqueous PCR was positive for HSV DNA and serologies were positive for HSV-2 IgG and negative for HSV-1 IgG, establishing the diagnosis of HSV-2 ARN in the context of meningitis. Intravenous ganciclovir was discontinued and intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg three times daily) was started once the etiologic diagnosis of HSV-2 meningitis was established.

The patient subsequently received bilateral intravitreal foscarnet injections every three days for two weeks, followed by weekly dosing. Over the course of two months, she received a total of five intravitreal injections of ganciclovir OU and five foscarnet injections OD and six foscarnet injections OS. After one week, she was placed on valacyclovir 1 gram three times daily by mouth and a tapering course of oral prednisone. Prednisolone acetate 1% (Predforte 1%, Allergan, Irvine, CA) was administered four times daily OU to treat the anterior chamber inflammation. The patient developed bilateral vitreous hemorrhages and combined tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment OU, prompting pars plana vitrectomy, membrane peel, endolaser, and silicone oil instillation OU. Dense fibrovascular proliferative membranes with neovascularization elsewhere developed in both eyes and led to a recurrent retinal detachment in the right eye. The retina remained partially attached in the left eye. Her final remained hand motions OU at her nine-months follow-up. After an extended discussion with the family regarding the poor visual prognosis given the profound ischemia and clinical course, additional surgery was deferred.

Discussion

Acute retinal necrosis was first described in 1971 by Urayama and colleagues as a clinical syndrome consisting of unilateral acute uveitis, diffuse necrotizing retinitis with periarteritis and retinal detachment.1 In 1978, Young and Bird used the term ‘BARN’ for bilateral acute retinal necrosis based on their observations of four patients with this unusual bilateral disease syndrome.5 In 1994, the American Uveitis Society defined clinical features of ARN essential to its diagnosis. These included one or more foci of retinal necrosis with discrete borders, peripheral retinal location, rapid progression in the absence of antiviral therapy, circumferential spread, occlusive vasculopathy predominantly involving the arterioles, prominent anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation, optic neuritis and scleritis.3

The precise factors contributing to the extreme severity of our patient’s disease condition and severe vision loss despite aggressive intravitreal and parenteral antiviral therapy likely included a combination of factors. We hypothesize that the delayed diagnosis of herpetic meningitis and the exposure to high-dose systemic corticosteroids without antiviral therapy led to rapid viral replication and an aggressive cascade of both inflammatory and vaso-occlusive pathways with acute, severe vision loss despite therapy.

Ganatra et al described clinical factors associated with the specific viral etiology implicated in ARN.2 In their study population of 30 patients, VZV and HSV-1 ARN were more common in patients greater than 25 years old whereas HSV-2 ARN was more common in younger patients. A clinical history of meningitis or encephalitis is more indicative of HSV as the viral etiology for ARN, which was observed in our patient.2 Other characteristics more commonly associated with HSV-2 ARN include antecedent systemic corticosteroid or trauma, a history of meningitis, presence of neonatal herpes infection, and preexisting chorioretinal scar.2,6

While our patient had no documented history of HSV infection, her headaches, cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis, and MRI abnormalities were consistent with HSV-2 meningitis; one prior study evaluating MRI imaging for viral encephalitis has shown that abnormal findings are most commonly identified on FLAIR and T2 scans.7 Prior reports have described the development of ARN either following or concurrent with both HSV-1 and HSV-2 encephalitis. 8,9 Bilateral disease has been reported predominantly in neonates and in immunosuppressed patients (e.g. patients on chemotherapy and following exposure to high-dose systemic corticosteroids). 10,11

The role of corticosteroids in the development of ARN or potentiation of the ARN syndrome is of particular interest since corticosteroids have been employed to decrease the severe inflammation in ARN.12 However, reports of corticosteroid exposure either preceding or temporally associated with necrotizing retinopathy warrant consideration. In 2003, Browning described two patients who developed ARN following an epidural steroid injection for back pain.13 Saatci et al described a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with high-dose systemic corticosteroids for presumed optic neuritis.14 Nakamoto et al reported two other patients who developed progressive outer retinal necrosis following corticosteroid treatment for findings initially consistent with an optic neuropathy.15 These findings further underscore the importance of a careful peripheral retinal examination prior to treatment of any optic neuropathy with systemic corticosteroid. Our patient received parenteral corticosteroids in the absence of antiviral therapy prior to her diagnosis of bilateral CRAOs in association with BARN in association with HSV encephalomeningitis, a constellation of disease findings, which has not been previously described in the literature.

While it is unknown whether the patient would have developed bilateral CRAO and potentially could have averted such a poor visual outcome in the absence of corticosteroids, the rapidity of the patient’s ophthalmic course suggests that caution with the use of high-dose systemic corticosteroids is warranted when ARN and meningitis or encephalitis are diagnostic considerations. Further research is needed to better define the underlying inflammatory and vaso-occlusive mechanisms underlying the destructive sequelae in the ARN syndrome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) to the Emory Eye Center and an NEI Core Grant for Vision Research (P30 EY 006360)

References

- 1.Urayama A, Yamada N, Sasaki T. Unilateral acute uveitis with retinal periarteritis and detachment. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 1971;(25):607–619. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganatra JB, Chandler D, Santos C, Kuppermann B, Margolis TP. Viral causes of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(2):166–172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland GN. Standard diagnostic criteria for the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Executive Committee of the American Uveitis Society. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(5):663–667. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang SW, Kim SK. Optic neuropathy and central retinal vascular obstruction as initial manifestations of acute retinal necrosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2001;45(4):425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(01)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young NJ, Bird AC. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62(9):581–590. doi: 10.1136/bjo.62.9.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cottet L, Kaiser L, Hirsch HH, Baglivo E. HSV2 acute retinal necrosis: diagnosis and monitoring with quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29(3):199–201. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misra UK, Kalita J, Phadke RV, et al. Usefulness of various MRI sequences in the diagnosis of viral encephalitis. Acta Trop. 2010;116(3):206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugitani K, Hirano Y, Yasukawa T, Yoshida M, Ogura Y. Unilateral Acute Retinal Necrosis 2 Months After Herpes Simplex Encephalitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010:1–5. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100215-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bristow EA, Cottrell DG, Pandit RJ. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis syndrome following herpes simplex type 1 encephalitis. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(11):1327–1330. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma L, Venkatesh P, Satpal G, Rathore K, Tewari HK. Bilateral necrotizing herpetic retinopathy three years after herpes simplex encephalitis following pulse corticosteroid treatment. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 1999;19(5):464–467. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199919050-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kychenthal A, Coombes A, Greenwood J, Pavesio C, Aylward GW. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis and herpes simplex type 2 encephalitis in a neonate. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(5):629–630. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.5.625f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau CH, Missotten T, Salzmann J, Lightman SL. Acute retinal necrosis features, management, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(4):756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browning DJ. Acute retinal necrosis following epidural steroid injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(1):192–194. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saatci AO, Ayhan Z, Arikan G, Sayiner A, Ada E. Unilateral acute retinal necrosis in a multiple sclerosis patient treated with high-dose systemic steroids. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30(5):629–632. doi: 10.1007/s10792-010-9380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamoto BK, Dorotheo EU, Biousse V, Tang RA, Schiffman JS, Newman NJ. Progressive outer retinal necrosis presenting with isolated optic neuropathy. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2423–2425. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147263.89255.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]