Abstract

Background

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are attractive candidates for therapeutic use, with the potential to replace deficient cells and to improve functional recovery in injury or disease settings. Here we test the hypothesis that human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) can secrete cytokines as a molecular basis to attenuate adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction (MI).

Methods and Results

Human iPSCs were generated from skin fibroblasts and differentiated in vitro using a small molecule based protocol. Troponin+ iPSC-CMs were confirmed by immunohistochemistry, quantitative PCR, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), and electrophysiological measurements. Afterwards, 2×106 iPSC-CMs derived from a cell line transduced with a vector expressing firefly luciferase and GFP were transplanted into adult NOD/SCID mice with acute left anterior descending (LAD) ligation. Control animals received PBS injection. Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) showed limited engraftment upon transplantation into ischemic myocardium. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of animals transplanted with iPSC-CMs showed significant functional improvement and attenuated cardiac remodeling when compared to PBS-treated control animals at day 35 (Ejection fraction: 24.5±1.3 vs. 14.5±1.5%; P<0.05). To understand the underlying molecular mechanism, microfluidic single cell profiling of harvested iPSC-CMs, laser capture microdissection (LCM) of host myocardium, and in vitro ischemia stimulation were used to demonstrate that the iPSC-CMs could release significant levels of pro-angiogenic and anti-apoptotic factors in the ischemic microenvironment.

Conclusions

Transplantation of human iPSC-CMs into an acute mouse MI model can improve left ventricular function and attenuate cardiac remodeling. Because of limited engraftment, most of the effects are possibly explained by paracrine activity of these cells.

Keywords: stem cell, cardiomyocyte, cell transplantation, molecular imaging, myocardial infarction, iPSCs, paracrine activation

Introduction

Despite therapeutic advancements, cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of death and a major cause of disability that affects more than 23 million patients worldwide, including 5.8 million people in the United States.1 Most of the clinically approved therapeutics for the treatment of ischemic heart disease following acute myocardial infarction (MI) focus on modulating hemodynamics to reduce early mortality, but do not facilitate cardiac repair that is needed to reduce the incidence of heart failure.2 Therefore, in recent years, cell therapy after MI has been a focus of intense research and debate.3, 4

Different cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), have been investigated in both pre-clinical and clinical studies5-11, but overall the studies yielded variable results and the basic mechanisms that underlie efficacious cell therapy remain unclear12. It has been proposed that the transplanted cells are able to release angiogenic factors, protect cardiomyocytes from apoptotic cell death, and recruit resident cardiac stem cells that facilitate cardiac repair13. Recently, several studies have reported the use of cardiomyocytes derived from ESCs (ESC-CMs) or from iPSCs (iPSC-CMs) in providing functional benefits following MI, although there has been no consensus about the protective mechanism induced by these differentiated cardiomyocytes14.

In this present study, we utilized a model of acute myocardial injury, coupled with molecular imaging techniques, to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of iPSC-CMs. Using cardiac MRI and pressure-volume (PV) loops, we demonstrated that transplanted iPSC-CMs led to improved cardiac function, despite limited retention of transplanted cells. We further characterized the effects of the local cardiac microenvironment upon transplanted cells on a single cell level. Specifically, when exposed to an ischemic microenvironment, iPSC-CMs were found to have increased expression of pro-angiogenic genes, which in turn modulate the surrounding area to render it more favorable for tolerance against ischemic damage. This suggests the presence of molecular cross-talk, which might be responsible for the observed improvement in cardiac function following MI. Collectively, our study indicates that transplanted iPSC-CMs could be an attractive therapeutic modality for MI, as they are capable of secreting pro-survival factors under harsh conditions to potentially aid recovery of the injured heart.

Methods

An extended Methods is available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Study Design

A schematic overview of the study is summarized in Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement. Ligation of the mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD) was performed in adult female NOD/SCID mice. Mice were randomized into 3 groups: (1) sham with no occlusion, (2) occlusion with 2×106 iPSC-CMs, and (3) occlusion with saline. The animals were injected in the peri-infarct zone with a total volume of 20 μL. Cell survival was monitored by serial optical bioluminescence imaging (BLI) using the same set of mice on days 2, 4, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, and 35 using D-Luciferin delivered intraperitoneally. Cardiac function was assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on day 7 and day 35 post-MI (N=8/group). Histological analysis was performed on hearts from randomly selected animals (N=5/group). Transplanted cells were harvested from a subset of animals in both LAD ligation (N=5) and sham (N=4) groups at 4 days post-cell delivery by explantation of the heart followed by collagenase digestion and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)-based collection of GFP+ cells. RNA was harvested and used for single cell qRT-PCR15, 16. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) of host myocardium proximal to transplanted cells was employed to analyze expression of proangiogenic genes after cell transplantation (N=4) as previously described17. Finally, in vitro experiments using iPSC-CMs under control and ischemic conditions were analyzed by FACS, RT-PCR, and Luminex cytokine profiling.

Culture and Maintenance of iPSCs

Fibroblasts from a healthy human donor were used and iPSCs were derived using lentiviral vectors carrying the Yamanaka reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and cMyc. Human iPSCs were grown to 90% confluence18, 19 on Matrigel-coated plates (ES qualified, BD Biosciences, San Diego) using a chemically defined E8 medium as previously described20. Medium was changed daily and cells were passaged every 4 days using Accutase (Global Cell Solutions).

Cardiac Differentiation

iPSCs were grown to 90% confluence and subsequently differentiated into beating cardiomyocytes using a small molecule-based monolayer method21 and as previously described22. Briefly, on day 0 cells were supplemented with a basal medium [RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen), 2% B27 supplement minus Insulin (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin], with the addition of CHIR99021, a selective inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) which activates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. On day 1, the medium was replaced with basal medium without CHIR99021 supplementation. On day 3, IWR-1, a Wnt antagonist, was added to basal medium for another 2 days. On day5 and subsequently on every other day until harvest, the medium was replaced with fresh basal medium.

Electrophysiological Recordings of iPSC-CMs

To record action potentials, contracting monolayers were enzymatically dispersed into single cells, and attached to 0.1% gelatin-coated glass coverslips as described previously23 and detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Animal Surgery and Cell Transplantation

Myocardial infarction (MI) was induced in NOD/SCID mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) by LAD ligation under 2% inhaled isoflurane anesthesia as described previously24. Mice were randomized into 3 groups: (1) sham with no occlusion, (2) occlusion with 2×106 iPSC-CMs, and (3) occlusion with saline. The animals were injected in the peri-infarct zone with a total volume of 20 μL using a 29-gauge Hamilton syringe. All operations were performed by a blinded microsurgeon. Study protocols were approved by the Stanford Animal Research Committee. Animal care was provided in accordance with the Stanford University School of Medicine guidelines and policies for the use of laboratory animals.

Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) of Cell Transplantation

Serial BLI (n=8/group) was performed on the same set of mice on indicated days using the Xenogen In Vivo Imaging System (Alameda, CA) as previously described25, 26. Recipient mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and were intraperitoneally injected with D-Luciferin (375 mg/kg body weight). Peak signals from a fixed region of interest (ROI) were obtained and signals quantified in photons/s/cm2/sr as previously described27.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

For evaluation of myocardial function, mice subjected to MI followed by injection with PBS or iPSC-CMs (n=8 per group) were randomly selected at day 7 and day 35 post-MI. The method as well as data analyses were performed as previously described15 and detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Invasive PV Loop Measurement

Animals receiving either iPSC-CMs (n=4) or PBS (n=4) following LAD ligation were assayed at day 35 following surgery. Simultaneous measurements of pressure and volume were obtained using a specialized conductance catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, Texas) as described previously26 and detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Tissue Fixation and Immunohistochemical Analysis

Histological analysis was performed on randomly selected hearts from mice subjected to MI with PBS or iPSC-CMs (n=5/group) as described previously26. Following intubation, the chest was opened and the heart was perfusion fixed for 2 min at 120 mmHg with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS via left ventricular stab. Fixed hearts were immersed in 30% sucrose overnight, embedded into OCT (TissueTek), frozen, and sliced into 8-micron thick frozen sections. Rabbit anti-human cardiac troponin T (ab45932, Abcam), mouse anti-alpha actinin (A7811, Sigma Aldrich), and rat anti-CD31 antibody (550274, BD Pharmingen) staining was carried out. Primary antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:200 (anti-cardiac troponin T), 1:600 (anti-alpha actinin), and 1:100 (anti-CD31). Signals were visualized with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594, anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647, and anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies). Image acquisition was performed on a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM 510 Meta, Gottingen, Germany) and ZEN software (Carl Zeiss). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson's trichrome staining were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Infarct size was determined as the average of five sections sampled at 2 mm intervals from the apex using the formula infarct size: [coronal infarct perimeter (epicardial plus endocardial)/total coronal perimeter (epicardial plus endocardial)] × 100. Infarct wall thickness was measured in Masson's trichrome stained sections by taking the average length of five segments along evenly spaced radii from the center of the LV through the infarcted free LV wall.

Single Cell Gene Expression Profiling of Transplanted iPSC-CMs

Transplanted cells were harvested from a subset of animals in both LAD ligation (n=5) and sham (n=4) groups at 4 days following delivery by explantation of the heart, followed by collagenase digestion and FACS-based collection of GFP+ cells. RNA was harvested and used for single cell qRT-PCR (Fluidigm) as detailed in the Supplementary Methods28.

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) of Host Myocardium Proximal to Transplanted Cells

To analyze expression of pro-angiogenic genes after cell transplantation, laser capture microdissection (LCM) of host myocardium surrounding transplanted cells was employed (n=4) and total RNA was extracted as described previously15 and detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

In Vitro Analysis of Paracrine Function

iPSC-CMs were subjected to simulated ischemia in vitro under hypoxic conditions at 37°C for 12 hours, adapted after29. Analysis of secreted material was performed using a Luminex-based platform (Affymetrix) as published previously24 and detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using SigmaStat 3.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The normality of data distribution and the homogeneity of variances were assessed by Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene's test, respectively. All values were expressed as mean + SEM. Linear regression analysis was performed to estimate the correlation between 2 variables. The differences between two independent groups were compared using Student's t test and differences among three or more groups were tested using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. With small sample sizes or when the normality test failed, Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used. For data with unequal variances between the groups, unpaired t test with Welch's correction was applied. To test serial changes in BLI signal, a one-way repeated-measures (RM) ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc analysis was conducted. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

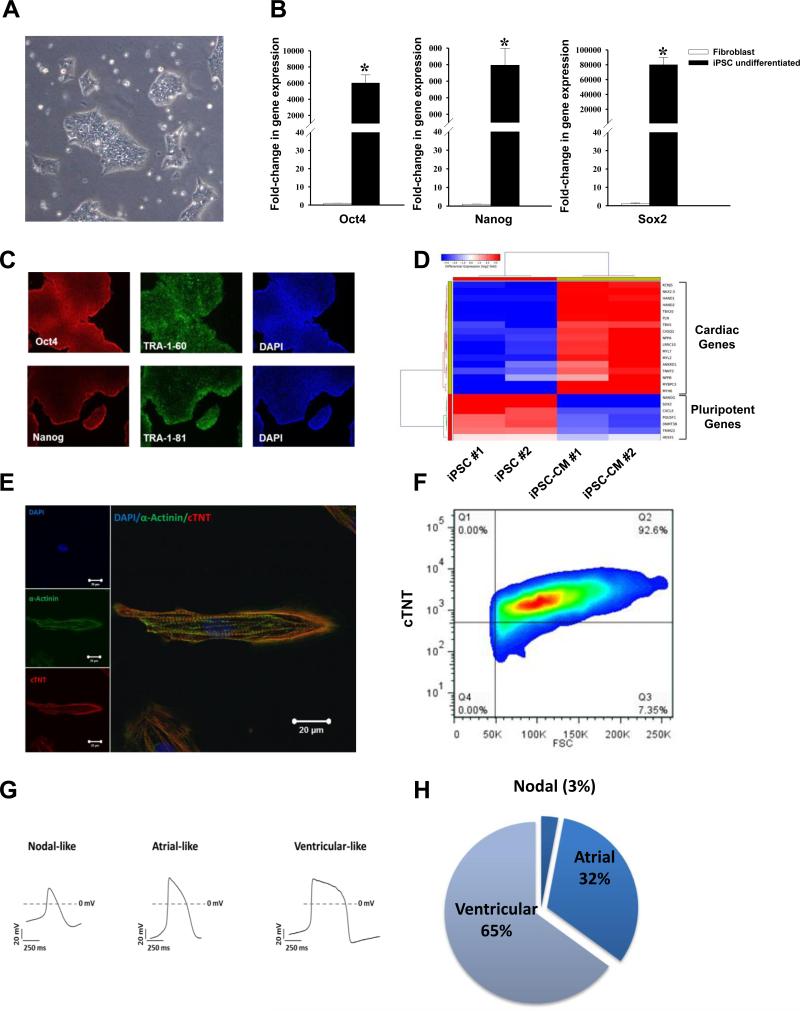

Generation and Characterization of iPSCs and iPSC-CMs

A human iPSC line was generated by lentiviral-mediated transduction of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc using primary human adult dermal fibroblasts obtained from a healthy patient (Figure 1A). The iPSC colonies revealed high gene expression levels of pluripotency markers such as Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 as assessed by RT-PCR (Figure 1B), and stained positive for pluripotency markers such as Oct4, Nanog, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81 when assessed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1C). As a definitive test for pluripotency, undifferentiated iPSCs were injected into immunocompromised NOD/SCID mice and were found to form teratomas at 8 weeks after transplantation that contain cell derivatives of all three germ layers (Figure IIA-C in the online-only Data Supplement). Next, iPSCs were differentiated to cardiomyocytes using a small molecule-based protocol30. Cells were grown on Matrigel and started contracting spontaneously at around day 10 of differentiation. RNA-sequencing of iPSC-CMs revealed an upregulation of cardiac genes along with a downregulation of pluripotent genes compared to undifferentiated iPSCs, demonstrating a successful conversion of iPSCs into cardiomyocytes (Figure 1D). Immunostaining of iPSC-CMs also revealed a marked expression of sarcomeric proteins such as α-sarcomeric actinin (α-Actinin) and Troponin T (Figure 1E). Overall, the differentiation efficiency was robust, with ~90% Troponin T+ iPSC-CMs as assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 1F). Functional electrophysiological characterization of the iPSC-CMs in vitro using single cell patch clamp technique demonstrated different types of cardiomyocytes with nodal-like, atrial-like, and ventricular-like action potential morphologies (Figure 1G). Overall, ~65% of the analyzed cells showed a ventricular-like morphology, ~32% atrial-like, and ~3% nodal-like (Figure 1H). Basic electrophysiological properties of the analyzed iPSC-CMs are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 1.

Characterization of undifferentiated iPSCs and in vitro differentiated iPSC-CMs. (A) Undifferentiated iPSCs were generated from human fibroblasts and grown on Matrigel. Representative image of an iPSC colony (passage 20). (B) Gene expression profile (RT-PCR) of undifferentiated iPSC showing upregulation of pluripotency markers Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog compared to fibroblasts. Values were normalized to GAPDH and expression values are relative to fibroblasts (N=4; *p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test). (C) Protein expression of pluripotency markers Oct4, Nanog, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81. Cell nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). (D) RNA-sequencing profiling of undifferentiated iPSCs and iPSC-CMs showing upregulation of cardiac markers and downregulation of pluripotency genes. (E) Expression of sarcomeric proteins α-actinin and Troponin T in iPSC-CMs as assessed by confocal microscopy. Cell nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 20 μm. (F) Representative troponin T expression of iPSC-CMs at day 30 after differentiation assessed by flow cytometry. (G) Representative cardiac AP recordings of nodal-like, atrial-like, and ventricular-like myocytes by patch clamp recordings. Dashes indicate 0 mV. (H) Quantification of patch clamp recordings shows a ventricular-like morphology in more than 60% of the analyzed cells (N=34). All iPSC-CMs were recorded around days 30-40 after cardiac differentiation.

Limited Engraftment of iPSC-CMs in the Ischemic Myocardium

We next investigated whether iPSC-CMs could survive and engraft after transplantation into ischemic myocardium. To enable in vivo tracking of cell engraftment longitudinally, the undifferentiated iPSC line was transduced with a lentiviral construct expressing firefly luciferase (Fluc) and eGFP (Figure 2A). After positive selection, transduced iPSCs highly expressed eGFP (Figure IIIA and B in the online-only Data Supplement). In vitro BLI demonstrated stable Fluc activity with a strong correlation between Fluc activity and cell number (R2=0.99; Figure 2B and 2C), validating the use of this imaging method for assessing cell survival in vivo. After differentiation, 2×106 iPSC-CMs were injected into NOD/SCID mice immediately after chronic LAD ligation. BLI at day 2 showed robust signal; however, serial imaging of the same animals demonstrated a significant drop by day 35 consistent with donor cell death over time (4.3×105±1.8×103 at day 2 vs. 1.2×104±1.1×103 p/s/cm2/sr at 5 weeks, P<0.05) (Figure 2D and 2E).

Figure 2.

iPSC-CM transplantation and survival in immunodeficient hosts. (A) Schematic of the reporter gene construct with a constitutive human MSCV promoter driving expression of Fluc and a constitutive human EF1 promoter driving eGFP, with a Puromycin cassette. (B-C) Correlation of cell count with Fluc signal (R2=0.99). (D) Limited cell engraftment after transplantation into immunodeficient NOD/SCID mice. (E) BLI signal quantification of panel D (N=8; *p<0.05 by one way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)).

Transplantation of iPSC-CMs Improves Cardiac Function after Acute Myocardial Infarction

Despite the limited engraftment of transplanted iPSC-CMs, which has also been reported with other cell types31, 32, we were interested to investigate the potential therapeutic efficacy of these transplanted cells in vivo. We compared the functional recovery between mice injected with PBS versus mice injected with iPSC-CMs after acute MI. Using cardiac MRI, left ventricular (LV) function as assessed by ejection fraction was found to be significantly reduced in both groups at 7 days post-MI with no discernible difference between control mice and iPSC-CM mice (Figure 3A and 3B; 19.2±1.8 vs. 20.6±1.1%). However, mice injected with iPSC-CMs had significantly improved LV function compared to PBS-treated controls when measured at 35 days post-MI (Figure 3C; 24.5±1.3% vs. 14.5±1.5%; P<0.05). These findings were further corroborated using PV loop measurement at day 35, which revealed less dilation of the left ventricle as well as higher contractility in mice treated with iPSC-CMs compared to control animals (Figure 3D and 3E).

Figure 3.

Improved cardiac function after iPSC-CM transplantation following acute myocardial infarction. (A-C) MRI analyses oat week 1 and week 5 after MI in animals injected with either iPSC-CMs or PBS (control). LVEF was significantly higher in iPSC-CM animals compared to control animals (N=8; *p<0.05 by Student's t-test). (D-E). Invasive hemodynamic analysis confirms MRI data, revealing a significant difference in various functional measures (ESV; end-systolic volume, EDV; end-diastolic volume, max pressure and dP/dt max) as assessed for hearts receiving iPSC-CMs versus PBS (N=4; *p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test).

Attenuated Cardiac Remodeling with Increased Neoangiogenesis and Reduced Apoptosis after iPSC-CM Transplantation

To better understand the preserved LV function after transplantation of iPSC-CMs in ischemic mice, we performed histological analysis of the myocardium by examining thin sections of the gross specimen via immunofluorescence microscopic examination. Histopathological analyses of tissue samples at week 4 post-LAD occlusion revealed a transmural MI in both groups (Figure 4A). Quantification of infarct size demonstrated significantly smaller infarct size in mice injected with iPSC-CMs compared to control mice (Figure 4B). Moreover, PBS-treated control mice showed a pronounced wall thinning and apical aneurysms compared to the treatment group injected with iPSC-CMs (Figure 4C). Microscopic examination at day 7 post-MI demonstrated the presence of GFP+ iPSC-CMs expressing α-sarcomeric actin and human-specific Troponin T (Figure 4D). However, the overall frequency of GFP+ iPSC-CMs was significantly decreased at day 28 (data not shown), which is consistent with the decrease in bioluminescence signals measured over this same period of time. Immunohistochemistry analysis of the peri-infarct area using CD31 staining revealed that the area of CD31+ capillaries per high power field was significantly higher in the group receiving iPSC-CMs compared to those only receiving PBS (Figure 4E and 4F). In addition, we used TUNEL staining to analyze the amount of apoptotic cells in the peri-infarct region. The number of apoptotic cells per high power field was significantly reduced in the mice receiving iPSC-CMs compared to those receiving PBS only (Figure IVA and IVB in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 4.

Attenuated cardiac remodeling after iPSC-CM transplantation. (A) Trichrome stained transverse sections of animals with either iPSC-CM or PBS-injection (control) at day 35 after MI. All hearts were cut at the level of the ventricular papillary muscles; red represents viable myocardium and blue represents collagen deposition indicative of scarring and fibrosis. (B) Infarct size quantification of (A) (N=5; *p<0.05 against control by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test). (C) LV wall thickness quantification of panel A (N=5; *p<0.05 against control by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test). (D) Engraftment of iPSC-CMs at 7 days after MI. Cells could be detected by GFP antibody and were found to co-express cardiac sarcomeric proteins α-actinin and Troponin T using confocal microscopy. Cell nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 100 μm (top left), 50 μm (top right), and 10 μm (bottom panel). (E) Representative CD31-stained transverse sections of animals with either iPSC-CM or PBS-injection (control) at day 35 after MI. (F) Quantification of panel E (N=5; *p<0.05 against control by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test).

Release of Pro-Angiogenic and Pro-Survival Factors by iPSC-CMs in Response to Ischemia In Vitro

Given that the majority of cells did not survive beyond 4 weeks post transplantation, we hypothesized that iPSC-CMs may release paracrine factors that promote angiogenesis and reduce apoptosis in the setting of ischemia, accounting for the functional benefit and attenuated cardiac remodeling that was observed. To explore this hypothesis, we investigated the angiogenic and anti-apoptotic potential of iPSC-CMs by using a simulated ischemic environment assay to assess the expression of genes encoding proangiogenic factors by real-time qPCR (Figure 5A). iPSC-CMs subjected to in vitro ischemia showed significantly increased expression of angiogenic and anti-apoptotic factors Vegf-a, Vegf-b, Ang1, Fgf-1, Egf, Il-1α, Pdgf-α, Tnf-α, Tgf-α, and Sdf-1α compared to normoxic conditions (Figure 5B). To confirm that iPSC-CMs are also able to secrete growth factors under ischemic conditions, we used the Luminex cytokine assay to analyze the supernatant of the control and ischemic iPSC-CMs. As seen in Figure 5C, ischemia led to a significant release of pro-angiogenic and pro-survival genes compared to normoxic conditions, indicating that iPSC-CMs can provide a framework that could potentially support new vessel growth and protect against cell death via secretion of paracrine factors.

Figure 5.

Differential expression of pro-angiogenic and pro-survival factors by iPSC-CMs in response to ischemia in vitro. (A) Schematic diagram depicting iPSC-CMs under control and ischemic conditions. Cells were subjected to PCR and supernatant was profiled using Luminex cytokine assay. (B) Gene expression analysis revealed that iPSC-CMs under ischemic conditions significantly increased expression of several pro-angiogenic and anti-apoptotic factors compared to normoxic condition (N=4; *p<0.05 by unpaired t test with Welch's correction). (C) Luminex cytokine array of iPSC-CMs under control and ischemic conditions showed significant release of cytokines in the supernatant of ischemic iPSC-CMs compared to control supernatant (N=4; *p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test).

Increased Expression and Secretion of Pro-Angiogenic and Pro-Survival Factors after iPSC-CM Transplantation In Vivo

After demonstrating the potential of iPSC-CMs to express and secrete pro-angiogenic and pro-survival cytokines under ischemic conditions in vitro, we next hypothesized that transplanted cells are also able to express and secrete growth factors and cytokines in vivo, which is the driver for neoangiogenesis and cell survival that generates cardioprotective effects. Because of the heterogeneous nature of transplanted cell populations, especially those derived from multipotent cell lines such as iPSCs and their derivatives, it is important to study the expression of genes at the single cell level16. Therefore, we injected the iPSC-CMs into the peri-infarct zone of mice immediately after MI or into the same anatomical location of control mice with non-infarct sham surgery (control). Four days after cell transplantation, hearts were explanted and digested to purify single GFP+ iPSC-CMs transplanted into ischemic vs. non-ischemic regions. Individually FACS-isolated iPSC-CMs were analyzed for expression of genes related to angiogenesis and apoptosis using the microfluidic single cell PCR platform (Figure 6A and 6B). ~90% of these isolated individual iPSC-CMs retained Troponin T+ expression (data not shown). A number of genes were significantly expressed in the iPSC-CMs injected into the border zone compared with iPSC-CMs injected into non-ischemic region, including Hif-1α, Vegf-α, Vegf-b, Ang1, Hgf, Fgf-2, Egf, Tgf-α, Tnf-α, and Sdf-1α (Figure 6C). Having shown that iPSC-CMs display a different gene expression profile upon exposure to ischemic stress, we sought to further confirm that transplanted cells are able to express and secrete growth factors and cytokines. We harvested the host myocardium surrounding the transplanted cells by LCM and performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR of pro-angiogenic and pro-survival genes at day 4 after MI. The remote nonischemic tissue of the same heart was used as internal controls. Vegf-α, Fgf-2, Ang1, and Hgf genes showed significantly higher levels in the peri-infarct area collected from mice treated with transplanted cells compared to those without cell injection (Figure 6D). Importantly, we found that injection of concentrated conditioned medium (CM) harvested from iPSC-CMs into acutely infarct mice hearts resulted in a modest but significant reduction of infarct size compared to cell-free control CM, although there was no difference between normoxic and hypoxic CM (Figure V in the online-only Data Supplement). Taken together, these results corroborated our in vitro findings suggesting that iPSC-CMs are capable of expressing and secreting a variety of proangiogenic and pro-survival factors under ischemic conditions, resulting in functional improvement and attenuated cardiac remodeling.

Figure 6.

Increased expression and secretion of pro-angiogenic and pro-survival factors after iPSC-CM transplantation in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram depicting injection of iPSC-CMs into mice undergoing sham or MI surgery. Four days later, hearts were explanted and injected iPSCCMs were isolated and profiled. (B) Representative GFP+ iPSC-CMs after Langendorff digestion. (C) Single cell gene expression profiling revealed that iPSC-CMs increased expression of several pro-angiogenic factors in ischemic conditions compared to sham (N=4-5; *p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test). (D) Laser capture microdissection (LCM) of peri-infarct myocardium surrounding the transplanted iPSC-CMs. Compared to mice receiving MI but no cell transplantation, peri-infarct myocardium surrounding transplanted cells had a significantly higher expression of pro-survival genes Vegfa, Ang1, Fgf2, and Hgf, both normalized against internal remote non-ischemic tissue (N=4; *p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney's rank sum test).

Discussion

A variety of different stem cell types have been investigated for their ability to repair the infarcted heart in both preclinical studies and human clinical trials12. The use of iPSC technology has added an additional cell source that may have potential clinical applications in this field, and one of its derivatives (i.e., iPSC-derived retinal pigment cells) is already in clinical trial in Japan.33 The major findings of this study are summarized below: (1) transplantation of iPSC-CMs into the acute MI mouse model resulted in limited engraftment; (2) despite limited engraftment, transplanted iPSC-CMs promoted cardioprotection and attenuated cardiac remodeling compared to PBS treated control animals; (3) mechanistically, iPSC-CMs at a single cell level could increase expression of pro-angiogenic and anti-apoptotic cytokines following ischemia in vitro and in vivo, which was associated with increased neovascularization and reduced apoptosis.

In our study, most of the transplanted iPSC-CMs failed to survive long term in the infarcted heart, highlighting one of the major bottlenecks of cell-based therapy. Precluding the possibility of immune rejection as immunodeficient mice were used in this study, the transplanted iPSC-CMs would still need to survive the initial highly inflammatory response associated with the acute infarct, integrate into the host myocardium in order to receive blood supply, and ultimately couple with residual host cardiomyocytes to contract synchronously, which is challenging considering the stark difference in heart beats between human iPSC-CMs and murine hearts. Multi-factorial strategies for cardiac repair are currently being developed to enhance survival of transplanted cells, including combining gene and cell therapy25, bioengineering methods such as 3-dimensional materials34, and genetic modification of cells35 which would hopefully overcome the issue of poor survival.

Despite the limited engraftment of iPSC-CMs, it was encouraging to observe preserved cardiac function in mice receiving iPSC-CMs compared to PBS at up to 5 weeks post-MI. The observation that actual cell engraftment is not needed to promote functional improvement points towards the possibility of paracrine factors secreted by iPSC-CMs as the driving force behind the beneficial effects. This is consistent with our findings of increased vascularity and reduced apoptosis in iPSC-CM treated mice compared to control mice, which may be sufficient to explain the transient protection observed here and is in accordance with the paracrine concept which has been robustly demonstrated in other cell types such as MSCs36-38.

The majority of studies to date have looked at secretion of paracrine factors in vitro without investigating the expression of these factors in an in vivo setting. Likewise, other groups have investigated the expression profile of paracrine factors after injection, but only at a total myocardial expression level, not necessarily examining the expression profile of the cells of interest39. Given the heterogeneous nature of iPSC-CMs (which are influenced by limitations in reprogramming, differentiation efficiency, and type of iPSC-CMs whether ventricular-, atrial-, or nodal-like), we used a novel microfluidic platform to examine the gene expression profile of injected iPSC-CMs in vivo at a single cell level. We have previously validated this platform to investigate the manner by which porcine iPSC-derived endothelial cells provided cardioprotection against MI15. In this study, we have extended the use of this platform to study the paracrine effects of human iPSC-CMs in vitro and in vivo for the first time, including the cross-talk effects afforded by paracrine molecules on the surrounding myocardium by laser capture microdissection (LCM). An initial in vitro comprehensive analysis of iPSC-CMs revealed that these cells had higher expression and also secreted paracrine factors when exposed to simulated ischemic conditions compared to normoxia. We further confirmed these findings in vivo by recovering individual transplanted iPSC-CMs from sham or infarcted mice, which revealed that iPSC-CMs in an ischemic heart had higher expression of paracrine factors. Notably, these released factors are able to modulate host myocardium, leading to a change in the milieu as measured by LCM analysis of myocardial tissue surrounding the site of engraftment. In-depth molecular analysis in the future would be beneficial to unravel the secretome of these iPSC-CMs, which could be utilized to further enhance paracrine signals as a new approach for eliciting cardioprotection.

In summary, we have shown that despite poor survival of iPSC-CMs in a murine model of MI, preservation of cardiac function was still observed and associated with increased vascularity and reduced apoptosis. Although engraftment was limited, transplanted iPSC-CMs in an ischemic microenvironment promote pro-angiogenic and anti-apoptotic paracrine factors, which can then modulate the ischemic heart to render it more resistant (i.e., resulting in increased vasculogenesis and decreased apoptosis) and to form a basis of molecular crosstalk, a concept which is well established in cancer studies but yet to be fully explored in cardiac regenerative mechanisms. In the future, further development of methods to improve survival of these iPSC-CMs would likely enhance their protective effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: We thank Jared Churko for RNA sequencing data generation and Ping Liang for electrophysiological characterization of iPSC-CMs. We are grateful for the funding support by American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 15POST22940013 (S-G.O), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (B.C.H., A.E. and S.D.), and by Fondation Leducq, NIH U01 HL09776, R01 HL113006, and CIRM DR2-05394 and TR3-05556 (J.C.W.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velagaleti RS, Pencina MJ, Murabito JM, Wang TJ, Parikh NI, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Long-term trends in the incidence of heart failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2057–2062. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.784215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Schneider MD. Unchain my heart: The scientific foundations of cardiac repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:572–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wollert KC, Drexler H. Cell therapy for the treatment of coronary heart disease: A critical appraisal. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:204–215. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noiseux N, Gnecchi M, Lopez-Ilasaca M, Zhang L, Solomon SD, Deb A, Dzau VJ, Pratt RE. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing akt dramatically repair infarcted myocardium and improve cardiac function despite infrequent cellular fusion or differentiation. Molecular Therapy. 2006;14:840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, Dib N, Strumpf RK, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, DeMaria AN, Denktas AE, Gammon RS, Hermiller JB, Jr., Reisman MA, Schaer GL, Sherman W. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D'Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, Beache GM, Wagner SG, Leri A, Hosoda T, Sanada F, Elmore JB, Goichberg P, Cappetta D, Solankhi NK, Fahsah I, Rokosh DG, Slaughter MS, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (scipio): Initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LE, Berman D, Czer LS, Marban L, Mendizabal A, Johnston PV, Russell SD, Schuleri KH, Lardo AC, Gerstenblith G, Marban E. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (caduceus): A prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O'Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiba Y, Fernandes S, Zhu WZ, Filice D, Muskheli V, Kim J, Palpant NJ, Gantz J, Moyes KW, Reinecke H, Van Biber B, Dardas T, Mignone JL, Izawa A, Hanna R, Viswanathan M, Gold JD, Kotlikoff MI, Sarvazyan N, Kay MW, Murry CE, Laflamme MA. Human es-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature. 2012;489:322–325. doi: 10.1038/nature11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miao Q, Shim W, Tee N, Lim SY, Chung YY, Ja KP, Ooi TH, Tan G, Kong G, Wei H, Lim CH, Sin YK, Wong P. Ipsc-derived human mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial strain of infarcted myocardium. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:1644–1654. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segers VF, Lee RT. Stem-cell therapy for cardiac disease. Nature. 2008;451:937–942. doi: 10.1038/nature06800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Heart regeneration. Nature. 2011;473:326–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalit PA, Hei DJ, Raval AN, Kamp TJ. Induced pluripotent stem cells for post-myocardial infarction repair: Remarkable opportunities and challenges. Circ Res. 2014;114:1328–1345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu M, Nguyen PK, Lee AS, Xu D, Hu S, Plews JR, Han L, Huber BC, Lee WH, Gong Y, de Almeida PE, Lyons J, Ikeno F, Pacharinsak C, Connolly AJ, Gambhir SS, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Microfluidic single-cell analysis shows that porcine induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells improve myocardial function by paracrine activation. Circ Res. 2012;111:882–893. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narsinh KH, Sun N, Sanchez-Freire V, Lee AS, Almeida P, Hu S, Jan T, Wilson KD, Leong D, Rosenberg J, Yao M, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Single cell transcriptional profiling reveals heterogeneity of human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1217–1221. doi: 10.1172/JCI44635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang M, Nguyen P, Jia F, Hu S, Gong Y, de Almeida PE, Wang L, Nag D, Kay MA, Giaccia AJ, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Double knockdown of prolyl hydroxylase and factor-inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor with nonviral minicircle gene therapy enhances stem cell mobilization and angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124:S46–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun N, Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, Wilson KD, Lee A, Jia F, Hu S, Cherry AM, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Feeder-free derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from adult human adipose stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15720–15725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908450106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, Sanchez-Freire V, Nguyen PK, Wang L, Han L, Yen M, Wang Y, Sun N, Abilez OJ, Hu S, Ebert AD, Navarrete EG, Simmons CS, Wheeler M, Pruitt B, Lewis R, Yamaguchi Y, Ashley EA, Bers DM, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen G, Gulbranson DR, Hou Z, Bolin JM, Ruotti V, Probasco MD, Smuga-Otto K, Howden SE, Diol NR, Propson NE, Wagner R, Lee GO, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Teng JM, Thomson JA. Chemically defined conditions for human ipsc derivation and culture. Nat Methods. 2011;8:424–429. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lian X, Hsiao C, Wilson G, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Azarin SM, Raval KK, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1848–1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu S, Wilson KD, Ghosh Z, Han L, Wang Y, Lan F, Ransohoff KJ, Burridge P, Wu JC. Microrna-302 increases reprogramming efficiency via repression of nr2f2. Stem Cells. 2013;31:259–268. doi: 10.1002/stem.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang P, Lan F, Lee AS, Gong T, Sanchez-Freire V, Wang Y, Diecke S, Sallam K, Knowles JW, Nguyen PK, Wang PJ, Bers DM, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Drug screening using a library of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes reveals disease specific patterns of cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2013;127:1677–1691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber BC, Ransohoff JD, Ransohoff KJ, Riegler J, Ebert A, Kodo K, Gong Y, Sanchez-Freire V, Dey D, Kooreman NG, Diecke S, Zhang WY, Odegaard J, Hu S, Gold JD, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Costimulation-adhesion blockade is superior to cyclosporine a and prednisone immunosuppressive therapy for preventing rejection of differentiated human embryonic stem cells following transplantation. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2354–2363. doi: 10.1002/stem.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong SG, Lee WH, Huang M, Dey D, Kodo K, Sanchez-Freire V, Gold JD, Wu JC. Cross talk of combined gene and cell therapy in ischemic heart disease: Role of exosomal microrna transfer. Circulation. 2014;130:S60–69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheikh AY, Huber BC, Narsinh KH, Spin JM, van der Bogt K, de Almeida PE, Ransohoff KJ, Kraft DL, Fajardo G, Ardigo D, Ransohoff J, Bernstein D, Fischbein MP, Robbins RC, Wu JC. In vivo functional and transcriptional profiling of bone marrow stem cells after transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:92–102. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.238618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao F, Lin S, Xie X, Ray P, Patel M, Zhang X, Drukker M, Dylla SJ, Connolly AJ, Chen X, Weissman IL, Gambhir SS, Wu JC. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006;113:1005–1014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Freire V, Ebert AD, Kalisky T, Quake SR, Wu JC. Microfluidic single-cell real-time pcr for comparative analysis of gene expression patterns. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:829–838. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA. Enhancing macroautophagy protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29776–29787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burridge PW, Keller G, Gold JD, Wu JC. Production of de novo cardiomyocytes: Human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong SG, Wu JC. Cortical bone-derived stem cells: A novel class of cells for myocardial protection. Circ Res. 2013;113:480–483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garbern JC, Lee RT. Cardiac stem cell therapy and the promise of heart regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garber K. Inducing translation. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis ME, Hsieh PC, Grodzinsky AJ, Lee RT. Custom design of the cardiac microenvironment with biomaterials. Circ Res. 2005;97:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173376.39447.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quijada P, Toko H, Fischer KM, Bailey B, Reilly P, Hunt KD, Gude NA, Avitabile D, Sussman MA. Preservation of myocardial structure is enhanced by pim-1 engineering of bone marrow cells. Circ Res. 2012;111:77–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangi AA, Noiseux N, Kong D, He H, Rezvani M, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, Melo LG, Morello F, Mu H, Noiseux N, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gnecchi M, He H, Noiseux N, Liang OD, Zhang L, Morello F, Mu H, Melo LG, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Evidence supporting paracrine hypothesis for akt-modified mesenchymal stem cell-mediated cardiac protection and functional improvement. FASEB J. 2006;20:661–669. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5211com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duran JM, Makarewich CA, Sharp TE, Starosta T, Zhu F, Hoffman NE, Chiba Y, Madesh M, Berretta RM, Kubo H, Houser SR. Bone-derived stem cells repair the heart after myocardial infarction through transdifferentiation and paracrine signaling mechanisms. Circ Res. 2013;113:539–552. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.