Abstract

India has a rich and diversified flora. It is seen that synthetic drugs could pose serious problems, are toxic and costly. In contrast to this, herbal medicines are relatively nontoxic, cheaper and are eco-friendly. Moreover, the people have used them for generations. They have also been used in day-to-day problems of healthcare in animals. 25% of the drugs prescribed worldwide come from plants. Almost 75% of the medicinal plants grow naturally in different states of India. These plants are known to cure many ailments in animals like poisoning, cough, constipation, foot and mouth disease, dermatitis, cataract, burning, pneumonia, bone fractures, snake bites, abdominal pains, skin diseases etc. There is scarce review of such information (veterinary herbals) in the literature. The electronic and manual search was made using various key words such as veterinary herbal, ethno-veterinary medicines etc. and the content systematically arranged. This article deals with the comprehensive review of 45 medicinal plant species that are official in Indian Pharmacopoeia (IP) 2014. The botanical names, family, habitat, plant part used and pharmacological actions, status in British Pharmacopoeia 2014, USP 36 are mentioned. Also, a relationship between animal and human dose, standardization and regulatory aspects of these selected veterinary herbals are provided.

Keywords: Indian Pharmacopoeia 2014, standardization, veterinary herbals

INTRODUCTION

Herbal medicines are being used by an increasing number of people as these products are considered to have no side effects or minimum side effects. In Asian and African countries, 80% of the population depends on traditional medicine for their primary health-care needs. Herbal medicines are the most lucrative form of traditional medicines, generating billions of dollars in revenue. Researchers look to traditional medicines as a guide to help, as 40% of the plants comprise key ingredients that can be used for prescription drugs.[1] It is reported that in 2011-2012, the herbal global market was worth $80 billion. India's herbal industry is worth around Rs 16,000 crores or US$ 4,000 million.[2]

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines traditional medicine (herbal medicine) as “the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness”.[3]

It is seen that about 25% of modern medicines have come from plants first used traditionally. In Africa, North America, and Europe, three out of four people living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) use some form of traditional medicine for various symptoms and conditions. In China, traditional medicine accounts for 30-50% of the total consumption. There are around 800 manufacturers of herbal products with a total annual output of US$ 1.8 billion in China. Traditional medicine is widely used in India, particularly in rural areas, where 70% of the country's population lives.[1]

Veterinary herbal medicines comprise plant-based medicines and their therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic application in animal health care. The application of herbal medicines in human health care and animal health care has a long history that can be traced back over millennia. In the rural areas of India, the veterinary medicines cover knowledge, skills, methods, practices, and beliefs of the smallholders about caring for their livestock. These smallholders are unable to spend on quality health of their livestock, mainly due to non-affordability, whereas high-end health care is mainly met by expensive yet effective synthetic drugs. The side effects of the synthetic drugs such as presence of antibiotic residues leads to antibiotic resistance in humans; the toxic metabolites remain in meat, and the byproducts of synthetic drugs become a matter of concern in the long-term usage of such drugs. Issues like these have prompted the search for the use of alternatives such as herbal preparations, as these are cheap and safe as compared to modern animal health-care systems.[4,5,6]

Indian Pharmacopoeia (IP) is an official regulatory document meant for overall quality control and assurance of pharmaceutical products marketed in India and thus, contributing to the safety, efficacy, and affordability of medicines. IP is published by the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission on fulfillment of the requirements of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940 and Rules 1945 under it. It contains a number of carefully chosen herbal monographs, extracts, and formulations. Each monograph of a herb in the IP specifies the botanical name according to the binomial system of nomenclature, specifying the genus, species, variety, and the quality specifications.[7]

Medicinal herbs contain a vast range of pharmacologically active ingredients and each herb has its own unique combination and properties. Many herbs (whole plants) contain ingredients which have several effects that are combined in the one medicine. It would be appropriate to weigh the risk-benefit ratio based on the scientific evidence and experience of a prescriber while prescribing such herbal medicines in the interest of animal health.

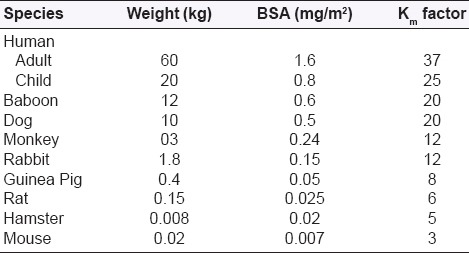

Relationship between animal dose and human dose

The appropriate translation of drug dosage from one animal species to another and the translation of animal dose to human dose are both very important from the point of safety and efficacy of drugs. Moreover, forced administration and mixing of drug with fodder are usually done to administer the drugs to animals. The Food and Drug Administration[8] has suggested that the extrapolation of animal dose to human dose is correctly performed through normalization to body surface area (BSA), which often is represented in mg/m2. The human dose equivalent can be more appropriately calculated by using the formula shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conversion of human equivalent dose to animal dose

Preparation of veterinary herbal medicines

Herbal medicines for veterinary use can be given or prepared in a number of ways:

Fresh herbs are chopped and mixed with food. It is perhaps the ideal way to give herbs when they are available

Dried herbs can be administered by their addition to food or making them into infusions or decoctions by adding hot water for internal or external use

Alcoholic tinctures are given directly or diluted in water, and given orally carefully using a syringe or dropper

Oil infusions or lotions are given externally, for example, by rubbing on sore joints

Commercially prepared tablets or powders are the most commonly seen form of herbal remedy.

Herbal drugs used in veterinary practice

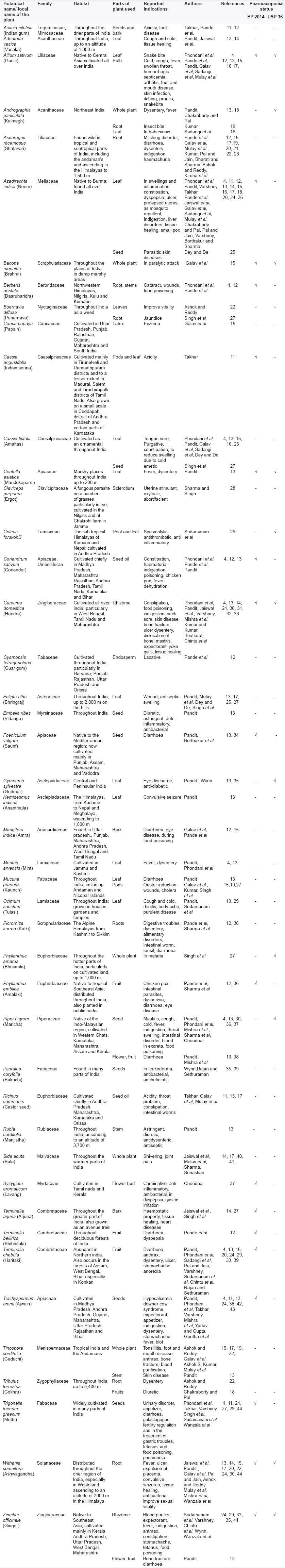

Medicinal plants for various animal diseases in different parts of India are compiled in IP 2014. Also, the official statuses of the herbs in the British Pharmacopoeia (BP) 2014 and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) 36 are summarized in Table 2.[7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]

Table 2.

Crude and processed herbs in IP 2014

Standardization and regulatory aspects of veterinary herbal medicines

Standardization of veterinary herbal medicines (crude drugs/extracts) is necessary to establish their quality, consistency, and reproducibility to ensure that one or more of the veterinary herbal medicine's key phytochemical ingredients or other ingredients are present in a defined amount. It is also necessary to implement quality control for batch-wise consistency, uniformity of dosage, stability, and for the detection of contamination/adulteration.[45] The identification of biologically active compounds in herbs is essential for quality control and also for determining the dose of the plant-based drugs. Also, knowledge of the appropriate dosage of these plant-based drugs is needed, as certain plants when used in small quantities are useful as veterinary medicines, whereas in large quantities are poisonous, e.g., Abrus precatorius.

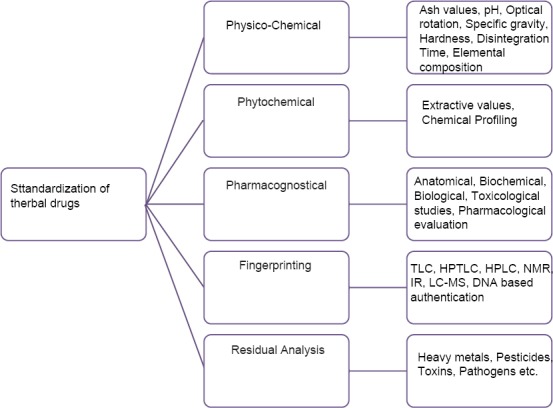

Standardization of herbal medicines is a difficult process because these medicines contain complex mixtures of different compounds. Thus, the herbs responsible for the medicinal effect are often unknown. Knowledge of the physicochemical properties of herbal medicines, along with other preformulation data, is necessary for the standardization and validation of active constituents. Various chemical, spectroscopic, and biological methods are also employed for the standardization. Some examples include infrared spectroscopy, liquid chromatography, high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC), nuclear magnetic resonance, mass spectroscopy, etc.[46] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Standardization of herbal drugs

Good manufacturing practices (GMP) is a system that ensures that the products manufactured are consistently produced, are controlled according to quality standards, and that they minimize those risks involved in production that cannot be eliminated through testing of the final product. GMP covers all aspects of production from the starting materials, premises, and equipment to the training, safety measures and personal hygiene of the staff. It also ensures that proper standard operating procedures are followed; the work environment is controlled; and quality assurance, packaging, and labeling are done in accordance with the requirements.[47,48] Various pharmacopoeias including the IP, Chinese Herbal Pharmacopoeia, British Herbal Pharmacopoeia, BP, USP, European Pharmacopoeia, Japanese Standards for Herbal Medicine, and the Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India have monographs of many herbs used for human care, but none of them state the herbal monographs used as veterinary medicines. Thus, these pharmacopoeias may also consider laying down monographs for herbs and herbal preparations specifically used in veterinary medicines so as to maintain their quality.

CONCLUSION AND PROSPECTS

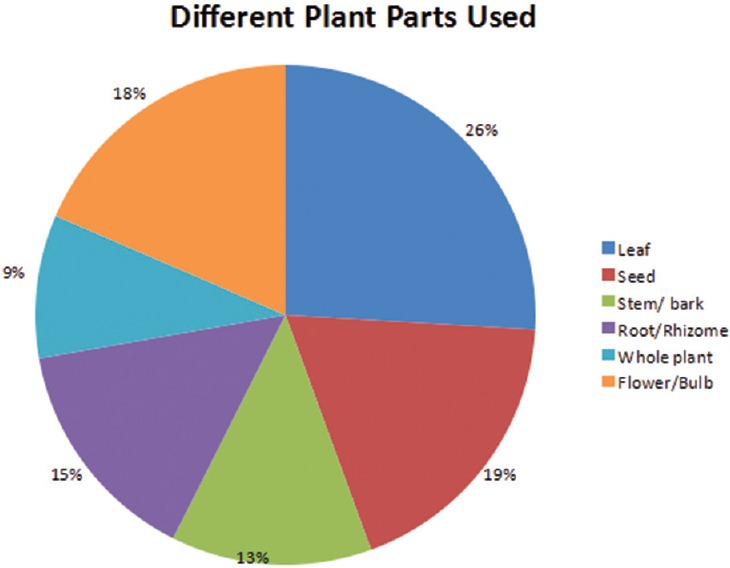

It is evident that most medicines mentioned in this review for animal health care are derived from leaves. Generally, fresh collected plant or plant parts are used for treatment. Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of different parts of plants used as veterinary medicines. Out of 57 crude herbs and 47 processed herbs/excipients in IP 2014, 40 crude herbs and 5 processed herbs/excipients are covered here. Among the 45 herbs mentioned, 18 are official in BP 2014 and 11 in USP 36. Thus, this article covers the wide scope of herbal drugs that can be used in the treatment of human diseases. Manufacturers are encouraged to use the IP standards with respect to these herbal medicines for the manufacture of veterinary herbal formulations.

Figure 2.

Pie diagram showing different plant parts used in veterinary

The data also revealed that plant preparations were used to treat a wide range of conditions such as cough, cold, diarrhea, dysentery, bone fractures, wounds, rheumatism, hair loss. Some of the drugs also have multiple indications in animal health care (Allium cepa, Azadirachta indica, Curcuma domestica, Piper nigrum, Trachyspermum ammi, Trigonella foenum-graecum, and Zingiber officinale).

In spite of the extensive modern programs implemented by government organizations and hospitals to uplift rural health care, these traditional treatments have remained popular. In some remote areas, people have great undocumented traditional knowledge about animal diseases, herbal treatments, formulations, etc., But due to modernization, this traditional veterinary knowledge is on the verge of extinction. The only means of acquisition of this knowledge is from what has been passed down over the generations and the lack of interest for traditional veterinary knowledge in the present generation is leading to its extinction.

Therefore, there is a need to prioritize the veterinary herbal sector. The herbal veterinary medicines are mainly sold at a relatively low cost as compared to modern medicines. While the herbal products are cheaper, the active ingredients of the medicinal plants are becoming increasingly expensive. As a result, herbal veterinary medicines are losing their edge over the allopathic drugs. Thus, there is also an urgent need to encourage research in this sector. Moreover, the quality specifications of veterinary herbal medicines need to be developed and the possibility of harmonization/collaboration efforts may be explored to take care of animal health care at the national and international levels. It can thus be concluded that there is still a need for both the validation of traditional claims (detailed pharmacognostical, phytochemical, and pharmacological investigations, etc.) and safety evaluations in appropriate models of these medicinal plants for their development and use as veterinary medicines.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunle OF, Eghavevba HO, Ahmadu PO. Standardization of herbal medicines- A review. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 2012;4:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kokate. Human resources, advanced infrastructure can spur Indian herbal industry growth. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.pharmabiz.com/NewsDetails.aspx?aid=73588&sid=1 .

- 3.who.int. World Health Organization. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/traditional/definitions/en/

- 4.Phondani PC, Maikhuri RK, Kal CP. Ethnoveterinary uses of medicinal plants among traditional herbal healers in Alaknanda catchment of Uttarakhand, India. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7:195–206. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i3.54775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay MK. Herbal medicines. Curr Sci. 1996;71:5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamboj VP. Herbal Medicine. Curr Sci. 2000;78:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IPC . The Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. Vol. 3. Ghaziabad: 2014. Indian Pharmacopoeia 2014; pp. 3165–284. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Drug Administration. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Anon; 2002. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Estimating the safe starting dose in clinical trials for therapeutics in adult healthy volunteers. U.S; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Pharmacopoeia. Vol. 4. UK: Council of Europe; 2014. British Pharmacopoeia Commission; pp. 43–399. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vol. 1. Rockville, Maryland, USA: United States Pharmacopoeial Convention; 2013. United States Pharmacopoeia 36 NF 31. United States Pharmacopoeia; pp. 1317–852. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takhar HK. Folk herbal veterinary medicines of southern Rajasthan. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2004;3:407–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pande PC, Tiwari L, Pande HC. Ethnoveterinary plants of Uttaranchal - A review. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2007;6:444–58. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandit PK. Inventory of ethnoveterinary medicinal plants of Jhargram division West Bengal, India. Indian Forester. 2010;136:1183–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaiswal S, Singh SV, Singh B, Singh HN. Plants used for tissue healing of animals. Natural Product Radiance. 2004;3:284–92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galav P, Jain A, Katewa SS. Ethnoveterinary medicines used by tribals of Tadgarh-Raoli wildlife sanctuary, Rajasthan, India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2013;12:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadangi N, Padhya RN, Sahu RK. Traditional veterinary herbal practices of Kalahandi district, Orissa. In: De Silva T, editor. Traditional and alternative medicines: Research and policy perceptive. 1st ed. New Delhi: Daya Publishing House; 2009. pp. 424–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulay JR, Dinesh V, Sharma PP. Study of some ethno-veterinary medicinal plants of Ahmednagar district of Maharastra, India. World J Sci Technol. 2012;2:15–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakraborty S, Pal SK. Plants for cattle health: A review of ethno-veterinary herbs in veterinary health care. Ann Ayurvedic Med. 2012;1:144–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar DD, Anbazhagan M. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants used in Perambalur district, Tamil Nadu. Res Plant Biol. 2012;2:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pal DC, Jain SK. Calcutta: Naya Prakash; 1998. Tribal Medicine; p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bharati KA, Sharma BL. Ethnoveterinary values of some herbaceous species of Sikkim. Ad Plant Sci. 2009;22:583–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashok S, Reddy PG. Some reports on traditional ethno-veterinary practices from savargaon areas of ashti taluka in beed district (m.s.) India. Int J Adv Bio Res. 2012;2:115–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiruba S, Jeeva S, Dhas SS. Enumeration of ethnoveterinary plants of Cape Comorin, Tamil Nadu. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2006;5:576–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varshney JP. Traditional therapeutic resources for management of gastrointestinal disorders and their clinical evaluation. In: Dwivedi SK, editor. Techniques for scientific validation and evaluation of ethnoveterinary practices. 1st ed. Izatnagar: IVRI Publisher; 1998. pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dey A, De JN. Ethnoveterinary uses of medicinal plants by the Aboriginals of Purulia District, West Bengal, India. Int J Bot. 2010;6:433–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borthakur SK, Sharma UK. Ethnoveterinary medicine with special reference to cattle prevalent among the Nepalis of Assam, India. In: Jain SK, editor. Ethnobiology in Human Welfare. 1st ed. New Delhi: Deep Publisher; 1996. pp. 197–99. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh A, Singh MK, Singh S. Traditional medicinal flora of District Buxar (Bihar, India) J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2013;2:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma PK, Singh V. Ethnobotanical studies in North West and trans Himalayas, V Ethnoveterinary medicinalplants used in Jammu and Kashmir, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 1989;27:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudarsanam G, Reddy MB, Nagarju N. Veterinary crude drugs in Rayalseema, Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Pharmacog. 1995;33:52–606. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra S, Jha V, Shaktinath J. Plants in ethnoveterinary practices in Darbhanga (North Bihar) In: Jain SK, editor. Ethnobiology in Human Welfare. 1st ed. New Delhi: Deep Publisher; 1996. pp. 189–93. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar R, Kumar AB. Folk veterinary medicines in Jalaun district of Uttar Pradesh, India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2012;11:288–95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattarati NK. Folk uses of plants in veterinary medicine in central Nepal. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:497–505. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chintu TU, Narainswami BK, Revi S. Ethnoveterinary medicine for dairy cows. In: Mathias E, Rangnekar, McCorkle CM, editors. Ethnoveterinay Medicine-Alternative for Livestock Development. Pune, India: BAIF Development Foundation Publisher; 1998. pp. 13–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borthakur SK, Nath K, Sharma TR. Inquiry into Old Lead: Ethnoveterinary medicine for treatment of elephants in Assam. Ethnobotany. 1998;10:70–4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wynn SG. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Publications; 2007. Veterinary herbal medicines; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma A, Shanker C, Tyagi LK, Singh M, Rao CV. Herbal medicine for market potential in India: An overview. Acad J Plant Sci. 2008;1:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choodnal C. Some folk medicines for livestock in Kerala. Folklore. 1988;29:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mishra S, Sharma S, Vasudevan P, Bhatt RK, Pandey S, Singh M, et al. Livestock feeding and traditional healthcare practices in Bundelkhand region of Central India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2010;9:333–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rajan S, Sethuraman M. Traditional veterinary practices in rural areas in Didigul district, Tamil Nadu, India. Indig Knowl Dev Monit. 1997;5:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma HO. Jiwaji University, Gwalior: Anon; 1991. Ethnobotanical studies of Sahariya tribes of Chambal division with special reference to Morena district. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sebastian MK. Plants used as veterinary medicines by Bhils. Intern J Trop Agri. 1984;2:307–10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yadav MP, Gupta S. Scope of ethnoveterinay practices in equine medicine. In: Dwivedi SK, editor. Techniques for Scientific Validation and Evaluation of Ethnoveterinary Practices. 1st ed. Izatnagar: IVRI Publisher; 1998. pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geetha S, Lakshmi, Ranjithakani P. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants of Kolli hills, Tamil Nadu. J Econ Tax Bot. 1996;12:289–91. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wanzala W, Zessin KH, Kyule NM, Baumann MP, Mathias E, Hassanali A. Ethnoveterinary medicine: A critical review of its evolution, perception, understanding and the way forward. Livest Res Rural Dev. 2005:17. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wani MS, Parakh SR, Dehghan MH. Herbal medicines and its standardization. Pharm Rev. 2007:5. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakravarthy BK. Standardization of herbal products. Indian J Nat Prod. 1993;9:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sane RT. Standardization, quality control and GMP for herbal drugs. Indian Drugs. 2002;39:184–90. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rawat RK, Khar RK, Garg A. Development and standardization of herbal formulations. Pharma Review. 2007;6:104–7. [Google Scholar]