Abstract

Background & objectives:

Alterations in microbial communities closely associated with the intestinal mucosa are likely to be important in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We examined the abundance of specific microbial populations in colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD) and controls using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) amplification of 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (16S rRNA).

Methods:

RNA was extracted from colonic mucosal biopsies of patients with UC (32), CD (28) and patients undergoing screening colonoscopy (controls), and subjected to RT-qPCR using primers targeted at 16S rRNA sequences specific to selected microbial populations.

Results:

Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas group and Enterobacteriaceae were the most abundant mucosal microbiota. Bacteroides and Lactobacillus abundance was greater in UC patients compared with controls or CD. Escherichia coli abundance was increased in UC compared with controls. Clostridium coccoides group and C. leptum group abundances were reduced in CD compared with controls. Microbial population did not differ between diseased and adjacent normal mucosa, or between untreated patients and those already on medical treatment. The Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio was significantly decreased in both UC and CD compared with controls, indicative of a dysbiosis in both conditions.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Dysbiosis appears to be a primary feature in both CD and UC. Microbiome-directed interventions are likely to be appropriate in therapy of IBD.

Keywords: Bacteroidetes, Crohn's disease, dysbiosis, Firmicutes, microbiota, ulcerative colitis

The inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) is thought to represent abnormal innate inflammatory reactions occurring in response to normal constituents of the gut microbiota in genetically predisposed individuals. The gut contains trillions of microbes which affect human health in many ways through effects on nutrition, metabolism and immunity1. The gut microbiota influence innate and adaptive immune responses in the intestine. Some of the microbial populations dampen immune and inflammatory responses through amplification of regulatory immune cells, while others induce inflammatory reactions2. IBD has been associated with a breakdown in the balance between putative species of protective versus harmful intestinal bacteria, a phenomenon that has been termed dysbiosis3.

Most of the studies on dysbiosis in IBD have examined the balance of specific microbial populations in the faeces. While the bulk of the gastrointestinal microbiota reside within the lumen, the subset that resides in the outer mucus layer covering the epithelial surface is likely to be most important in the gut microbial interaction with the innate immune system4, and therefore, it is most likely to have a bearing on the pathogenesis of IBD. Several studies, including one from India, have examined colonic mucosal bacterial populations in IBD and demonstrated alterations in the balance between putative beneficial and harmful bacterial populations5,6. The mucosa-associated bacteria are difficult to study because of their low numbers. Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) targeting 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) molecules is more than 100-fold sensitive and specific than qPCR alone in quantitating the microbial population because of the high copy number of targeted rRNA molecules7. Moreover, measuring 16s rRNA rather than the DNA (16S rRNA gene) identifies actively transcribing bacteria, which are more likely to affect intestinal immune reactions and thus have a greater bearing on human health than inactive or dead bacteria8.

The primary objective of the present study was to determine whether there were alterations in specific actively transcribing bacterial populations in the colonic mucosa of IBD patients compared to control volunteers. The secondary objectives were to determine whether there were differences in the actively transcribing bacterial populations between normal and abnormal mucosa of IBD patients, and to determine whether the balance and distribution of the microbial populations were influenced by the severity of mucosal inflammation or by medical therapy.

Material & Methods

The participants were recruited from the Gastroenterology and Inflammatory Bowel Disease clinics of the Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India, from December 2008 to December 2010. Consecutive patients with IBD undergoing colonoscopy were recruited as the case group, while controls were recruited from patients with haemorrhoidal bleeding referred for colonoscopy to exclude neoplasia. IBD diagnosis and characterization was based on standard consensus criteria9. Patients were investigated as per the usual clinical protocol of the department.

The participants provided written informed consent for the additional biopsies that were taken for study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Colonoscopies were performed after colonic lavage using orally administered polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution. Mucosal biopsy samples were obtained using standard biopsy forceps from endoscopically normal mucosa of the colon in controls and from abnormal or ulcerated mucosa in patients with IBD. In patients with CD and in UC patients with limited disease, apparently normal mucosa at least 5 cm from endoscopically abnormal areas was also biopsied for the study. Mucosal biopsies were immediately washed in sterile saline, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until processing. Zoetendal et al10 examined mucosal biopsies from different regions of the colon and showed that the mucosal bacterial community in the human colon was uniformly distributed throughout the colon with little variation by location. In our study, since biopsies from IBD patients included both normal and ulcerated mucosa from different regions of the colon, the normal and ulcerated biopsies were matched by region of the colon.

Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR): RNA was extracted from the biopsies using Tri reagent (Sigma, USA), following manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration in the samples were measured by spectrometry (Nanodrop, Thermo Scientific, USA). RNA samples (250 ng per biopsy sample) were converted to cDNA, using reverse transcriptase core kit (Eurogentec, Liege, Belgium). RNase pretreatment was not used7. The reverse transcription reaction mix was prepared on ice and contained final concentration of 1X buffer, 5mM MgCl2, 500 μM of each deoxy nucleotide phosphate (dNTPs), 2.5 μM random nonamer, 0.4 U/μl of RNAse inhibitor, 1.25 U/μl of EuroScript RT, 250 ng of total RNA and RNase free water to adjust the final volume to 10 μl. The cDNA conversion was carried out in a PTC-150 MiniCycler (MJ Research, USA) using a cycling protocol with an initial step for 10 min at 25 °C, followed by a reverse transcriptase step for 30 min at 48 °C and a final inactivation step for 5 min at 95 °C.

Diluted cDNA samples were then amplified in quantitative PCR. Amplification and detection were carried out in 96-well plates with Mesa Green qPCR MasterMix Plus for SYBR® Assay I dTTP (Catalog number RT-SY2X-03+NR WOUN, Eurogentec, Liege, Belgium) to quantify total bacteria and the specific bacterial populations listed in Table I. Each reaction was done in duplicate in a final volume of 20 µl with 2X MasterMix, 250 nM final concentration of each primer, and 2 µl of DNA sample. Quantification was performed in a real time PCR instrument, the Chromo 4 thermocycler coupled to a fluorescence detector (Biorad, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 20 sec, annealing temperature as shown in Table II for each bacterial population, and final elongation at 72°C for 30 sec. Fluorescence quantitation was analyzed using the Opticon monitor system software v. 3 (Biorad, USA). A dissociation step was added and melting curves were analyzed to confirm the identity and fidelity of amplification of SYBR Green products.

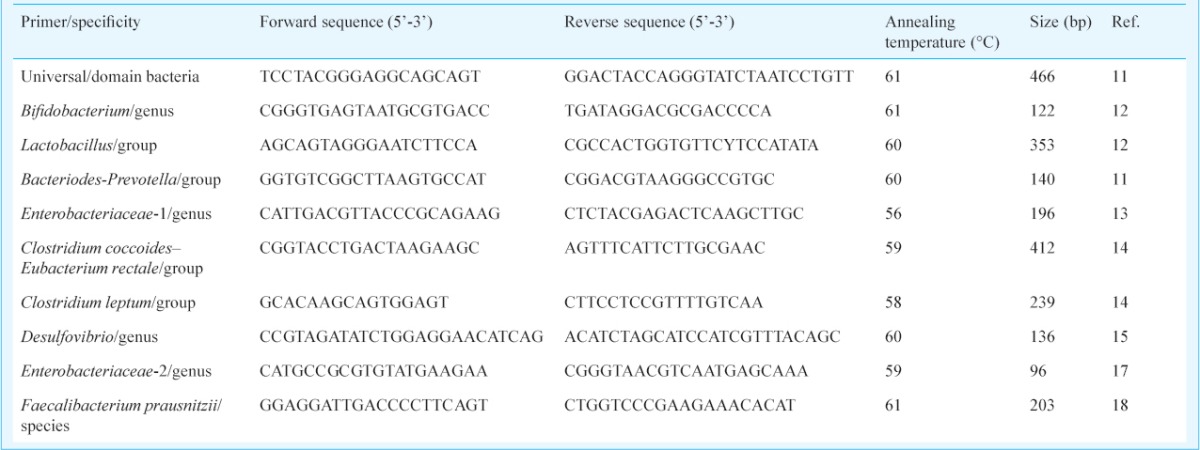

Table I.

Primers used in this study and amplicon sizes

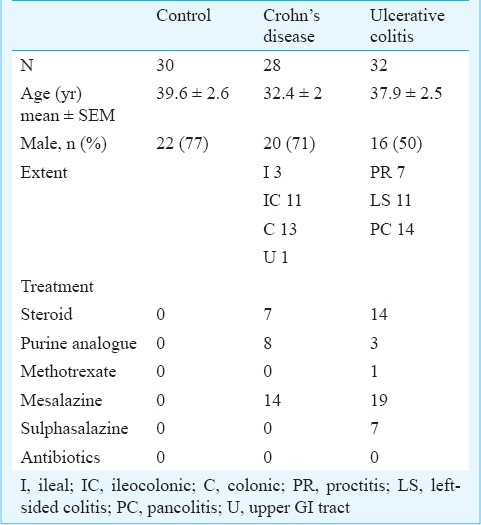

Table II.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

Details of the 16S rRNA-targeted primers used in this study and their specificities are described in Table I11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. These primers were purchased from Bioserve Biotechnologies (Hyderabad, India). The Opticon 3.1 (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) software, provided with the instrument, plotted the rate of change of the relative fluorescence units (RFU) with reference to time (T) (-d (RFU)/dT) on the Y-axis versus the temperature on the X-axis, with the curve peaking at the melting temperature. Quantification was based on the fluorescence intensity obtained from the intercalated SYBR Green dye. The cycle number at which the signal was first detected - the threshold cycle (Ct) - correlated with the original concentration of DNA template. DNA copy was not expressed as absolute number but was expressed as the relative abundance of the specified microbial population, being calculated from the Ct at which DNA for each target bacterial population was detected relative to the Ct at which universal bacterial DNA was detected during amplification, using the formula 2-ΔCt, where ΔCt = Ct [Bacteria of interest] - Ct [Universal bacteria], and expressed by the software as the relative fold difference. This relative quantification was done automatically by the Opticon 3.1 software. The relative abundance of the target bacterial population was thus the ratio of the target bacterial rRNA compared to universal rRNA, providing a quantitative comparison between different samples. The ratio calculated for each of the duplicate samples always correlated well with the other, with an adjusted R2 in the region of 0.8011.

Statistical analysis: The quantitative PCR was done with two technical replicates for each sample. The mean of the relative difference was taken for duplicate. The relative difference for each bacterial population in each study group (UC, CD, control) was expressed as mean±SEM, and the significance of differences between groups was assessed using unpaired t test with Welch correction for unequal variances.

Results

Thirty control participants, 28 patients with CD and 32 patients with UC were included in the study. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are described in Table II.

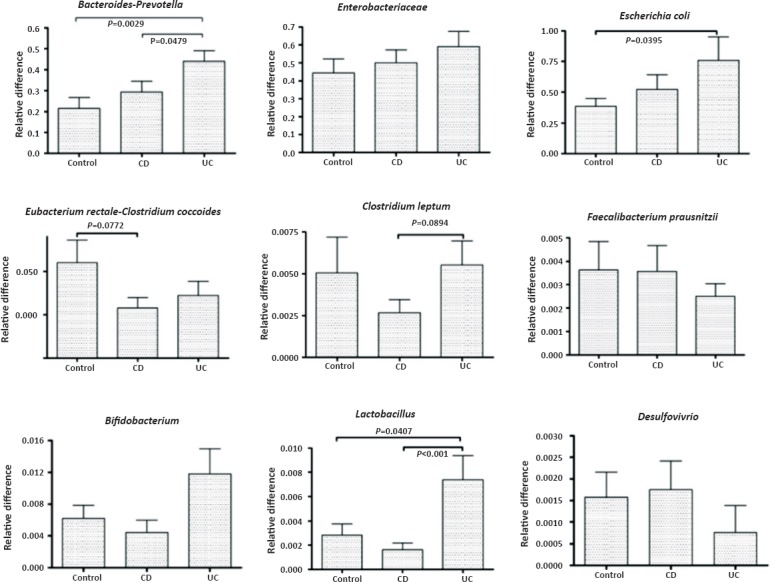

Differences in mucosal microbiota between controls and IBD patients: The two major microbial communities associated with the mucosa were the Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas group and the family Enterobacteriaceae. The Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas group was significantly more abundant in UC compared with controls as well as CD (Fig. 1). Enterobacteriaceae, a major aerobic bacterial group, was not significantly different between the groups. However Escherichia coli, a constituent of Enterobacteriaceae, was significantly more abundant in the mucosa of patients with UC. Lactobacillus group bacteria were also significantly increased in UC compared with controls or CD (Fig. 1). Clostridium coccoides-Eubacterium rectale group was significantly less abundant in CD mucosa compared with controls and Clostridium leptum group was significantly less abundant in CD compared to UC mucosa (Fig. 1). The other microbial populations tested were not significantly different between the study groups.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative representation of the various mucosa-associated bacterial populations in controls, patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). The bars represent mean ± SEM of the relative difference which is the fold amplification of sequences for the target population relative to amplification of universal bacterial domain sequences. significant differences (ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett's test) are shown.

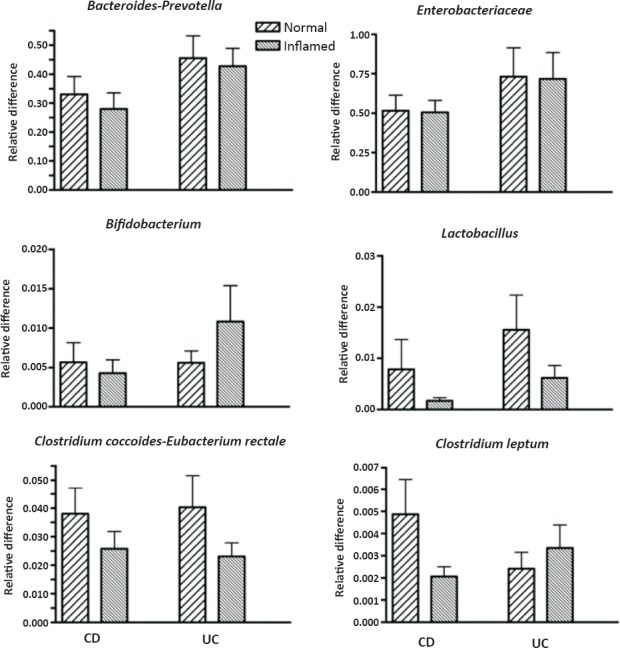

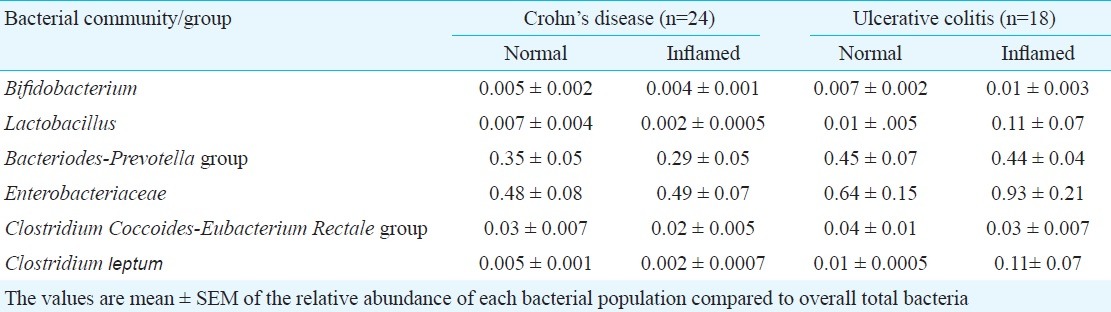

Differences in mucosal microbiota between normal and inflamed areas of the colon: Mucosal inflammation or ulceration may potentially alter the abundance of microbial population by altering the microenvironment necessary for the association of these microbiota with the mucosa. The relative abundance of mucosal microbiota between normal and inflamed colonic mucosa was compared in patients with IBD (Fig. 2). In 24 patients with CD, paired biopsies were available from both normal and inflamed areas of the colon. There were no significant differences in microbiota composition between normal and inflamed areas (Table III). Paired biopsies from normal and inflamed areas were available in 18 patients with UC. Again, there were no significant difference in microbiota composition between normal and inflamed mucosa (Table III).

Fig. 2.

Bacterial populations in ulcerated and normal colonic mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Bars represent mean ± SEM of the relative difference (fold amplification with reference to amplification of universal bacterial domain sequences). None of the differences between normal and ulcerated mucosa for each bacterial population was significant.

Table III.

Bacterial populations in biopsies from normal areas and from inflamed areas in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis

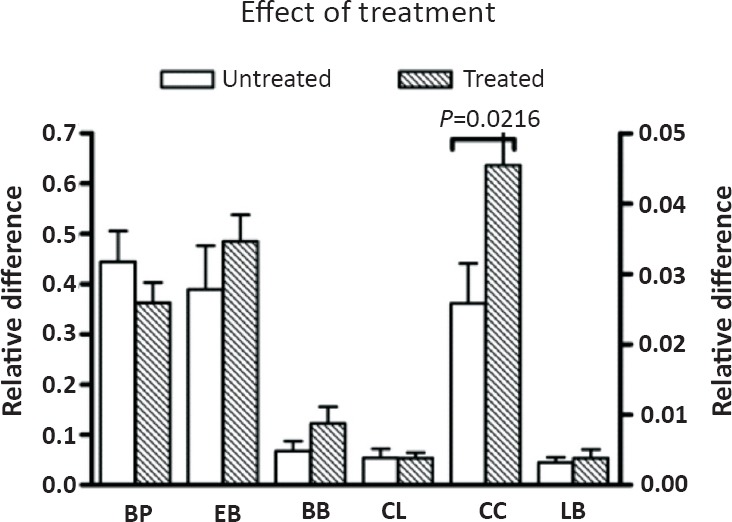

Effect of prior treatment on mucosal bacteria in IBD: Medical therapy of IBD can potentially alter microbiota composition. We compared mucosal bacteria in treatment-naïve IBD (CD and UC) patients with those who were receiving treatment at the time of biopsy. There were no significant differences in the mucosal microbiota between the two groups, except for Clostridium coccoides-Eubacterium rectale that was significantly more abundant in patients on therapy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bacterial populations in ulcerated mucosa of treatment-naïve or treated patients with IBD. Bars represent mean ± SEM of the relative difference which is the fold amplification of sequences for the target population relative to amplification of universal bacterial domain sequences. significant differences (unpaired t test with Welch's correction) are indicated in the Figure. Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas and Enterobacteriaceae are depicted on the left Y-axis; the remaining bacterial populations are depicted on the right Y-axis. BP, Bacteroides-prevotella-Porphyromonas; EB, Entero-bacteriaceae; BB, Bifidobacteria; CL, Clostridium leptum; CC, Clostridium coccoides; LB, Lactobacillus.

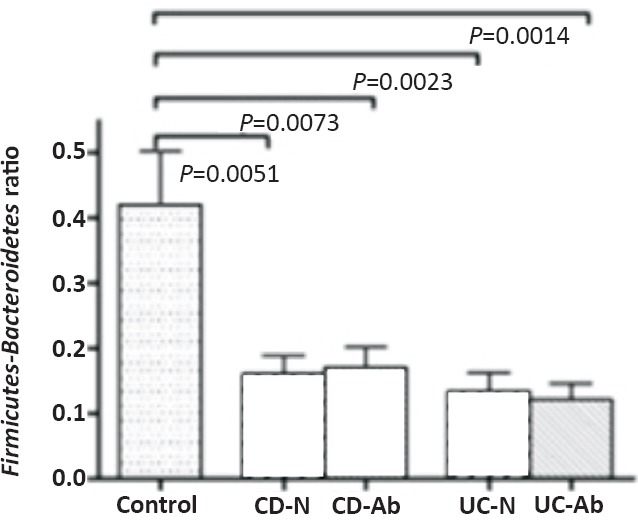

Ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in the mucosa: Clostridium coccoides-Eubacterium rectale (cluster XIV) and Clostridium leptum (cluster IV) groups represent the major constituents of phylum Firmicutes among the colonic microbiota, while Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas group represents the major constituent of phylum Bacteroidetes in the colonic microbiota. The ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes has been used to express the degree of dysbiosis in IBD. We, therefore, examined the ratio of Clostridium (sum of the two Clostridium clusters measured) to Bacteroides among the mucosal microbiota as a measure of dysbiosis. This ratio was significantly reduced in both forms of IBD, in both inflamed and normal mucosa, and regardless of treatment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Ratio of Firmicutes (C. coccoides plus C. leptum) to Bacteroidetes in the mucosal microbiota. The Figure shows the ratio in patients with CD and UC. CD-N and CD-Ab refer to Crohn's disease normal and abnormal mucosa. UC-N and UC-Ab refer to ulcerative colitis normal and abnormal mucosa. Significant P values are shown above the bars in the Figure. None of the other differences was significant. IBD biopsies showed a significantly lower ratio compared with controls.

Discussion

We report that Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas and Enterobacteriaceae were the most abundant microbial population associated with the colonic mucosa. By contrast, Firmicutes (principally clostridia) which are the most abundant constituents of the colonic luminal microbiota, were much less abundant in the mucosa. Importantly, our findings confirmed the existence of a dysbiosis in the mucosa in IBD patients that did not appear to be secondary to the presence of mucosal inflammation.

Clostridium coccoides group, including Eubacterium rectale, constitutes Clostridium cluster XIV, while Clostridium leptum group, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, is the major constituent of Clostridium cluster IV. Changes described in the faeces in CD include reductions in number of bacteria belonging to these two clusters, which are important in carbohydrate fermentation and short chain fatty acid (particularly butyrate) production19. Changes described in the faecal microbiota, at the phylum level, include increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, and reduced abundance of Firmicutes in the faeces of patients with CD20.

In contrast to the above studies of faecal microbiota, studies of the mucosal microbiota in IBD have used a variety of approaches and resulted in variable findings. Invasive-adherent E. coli have been reported in the ileal mucosal biopsies of patients with ileal CD21. Hartley et al22 isolated greater numbers of Bacteroides species from rectal biopsies of patients with active UC than from patients with inactive disease. Using molecular techniques, Bibiloni et al23 reported an increase in unclassified bacteria belonging to phylum Bacteroidetes in biopsies from CD patients and an increase in Porphyromonas species in biopsies from UC patients. Verma et al5 showed that Bacteroidetes population decreased in IBD patients compared to controls. In the present study, Bacteroides-Prevotella-Porphyromonas group was increased in the mucosa of UC patients compared with CD and controls. The differences between the two studies, both based in India, are likely to reflect the use of different primers to quantitate the bacterial population in these two studies. As in the above Indian study5, we also found decrease in the numbers of Clostridium in the mucosa of patients with CD. Swidsinki et al24 investigated the mucosal bacteria by in situ hybridization in biopsies where the mucus layer was retained, and found reduced abundance of bacteria belonging to the C. coccoides-E. rectale group and increased abundance of Bacteroides in patients with IBD compared to those with irritable bowel syndrome. Reduced abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in ileocolonic mucosal biopsies from patients with CD has also been reported25. Increased populations of phylum Bacteroidetes and reduced populations of phylum Firmicutes in the mucosa of IBD, especially CD, patients have also been reported. Quantitation of 16S rRNA in mucosal biopsies suggested that E. coli were both abundant and transcriptionally very active in both forms of IBD, while transcription of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes was suppressed in CD26. The present study was generally consistent with the above studies, showing an increase in the relative abundance of Bacteroides and E. coli in the mucosa of UC patients and decrease in relative abundance of Clostridium clusters XIV and IV in CD. Differences between studies may relate to differences in techniques for identification and quantitation, differences in diet of the individuals, and to restricted sample sizes in some studies.

The present study did not find significant differences in the mucosa-associated bacteria between apparently normal and inflamed mucosa in patients with IBD. In an earlier study comparing ulcerated and non-ulcerated mucosa in CD and UC, increases in Bacteroidetes and reduction in Firmicutes were more likely to be observed in ulcerated mucosa than in non-ulcerated mucosa; however, the numbers studied were small and there was considerable inter-individual variability27. In another study, bacterial community diversity was found to be less in ulcerated mucosa compared to non-ulcerated mucosa; however, that study did not attempt to generate microbial quantitative data28. The present study used RT-qPCR to quantitate specific microbial populations, and did not show significant differences in relative microbial abundance between ulcerated and non-ulcerated areas.

Bacteroides are important commensal bacteria that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease29. On the other hand, microbes belonging to the Clostridium clusters XIV and IV are important and major constituents of the normal colonic microbiota. The alteration in the ratio between Clostridium species which are considered beneficial and Bacteroides which are considered aggressive, is an indicator of dysbiosis in patients with IBD. The Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in faeces is very similar to the above and has been considered as an indicator of human gut microbiota status. An increase in Firmicutes characterizes obesity1 while an increase in Bacteroidetes has been reported to occur with ageing30. While one study suggests that the ratio of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii to E. coli is the important factor in dysbiosis, it is possible that the specific microbial imbalance may vary in different communities and countries. Understanding this better will obviously be of importance when considering therapies to counter dysbiosis. Another study done from north India which looked at mucosal microbiota in ulcerated areas, did not examine bacterial populations in normal mucosa of IBD patients5.

In conclusion, there were alterations in the mucosa-associated microbiota in both UC and CD characterized by reduction in abundance of microbes belonging to phylum Firmicutes relative to microbes belonging to phylum Bacteroidetes. The microbial populations did not significantly differ between normal and inflamed mucosa or between untreated and treated patients. These findings suggested that dysbiosis was a primary feature of both forms of IBD and that microbiome-directed interventions could be appropriate targets for therapy of IBD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Ramakrishna BS. Role of the gut microbiota in human nutrition and metabolism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 4):9–17. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 2011;474:327–36. doi: 10.1038/nature10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur N, Chen CC, Luther J, Kao JY. Intestinal dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:211–6. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.4.17863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson ME, Larsson JM, Hansson GC. The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host-microbial interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4659–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006451107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma R, Verma AK, Ahuja V, Paul J. Real-time analysis of mucosal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4279–82. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01360-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker AW, Sanderson JD, Churcher C, Parkes GC, Hudspith BN, Rayment N, et al. High-throughput clone library analysis of the mucosa-associated microbiota reveals dysbiosis and differences between inflamed and non-inflamed regions of the intestine in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Asahara T, Matsumoto K, Takada T, Nomoto K. Establishment of an analytical system for the human fecal microbiota, based on reverse transcription-quantitative PCR targeting of multicopy rRNA molecules. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1961–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01843-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sokol H, Lepage P, Seksik P, Doré J, Marteau P. Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis of fecal 16S rRNA reveals active Escherichia coli in the microbiota of patients with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3172–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02600-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouyang Q, Tandon R, Goh KL, Pan GZ, Fock KM, Fiocchi C, et al. Management consensus of inflammatory bowel disease for the Asia-Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1772–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoetendal EG, von Wright A, Vilpponen-Salmela T, Ben-Amor K, Akkermans AD, de Vos WM. Mucosa-associated bacteria in the human gastrointestinal tract are uniformly distributed along the colon and differ from the community recovered from feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3401–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3401-3407.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balamurugan R, Janardhan HP, George S, Raghava MV, Muliyil J, Ramakrishna BS. Molecular studies of fecal anaerobic commensal bacteria in acute diarrhea in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:514–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815ce599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Gratadoux JJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16731–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed S, Macfarlane GT, Fite A, McBain AJ, Gilbert P, Macfarlane S. Mucosa-associated bacterial diversity in relation to human terminal ileum and colonic biopsy samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7435–42. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinttila T, Kassinen A, Malinen E, Krogius L, Palva A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in faecal samples by real-time PCR. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:1166–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Kado Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, et al. Quantitative PCR with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers for analysis of human intestinal bifidobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:167–73. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.167-173.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balamurugan R, Rajendiran E, George S, Samuel GV, Ramakrishna BS. Real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification of specific butyrate-producing bacteria, Desulfovibrio and Enterococcus faecalis in the feces of patients with colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huijsdens XW, Linskens RK, Mak M, Meuwissen SG, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Savelkoul PH. Quantification of bacteria adherent to gastrointestinal mucosa by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4423–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4423-4427.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lay C, Sutren M, Rochet V, Saunier K, Dore J, Rigottier-Gois L. Design and validation of 16S rRNA probes to enumerate members of the Clostridium leptum subgroup in human faecal microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:933–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang S, Denman SE, Morrison M, Yu Z, Dore J, Leclerc M, et al. Dysbiosis of fecal microbiota in Crohn's disease patients as revealed by a custom phylogenetic microarray. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:2034–42. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joossens M, Huys G, Cnockaert M, De Preter V, Verbeke K, Rutgeerts P, et al. Dysbiosis of the faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn's disease and their unaffected relatives. Gut. 2011;60:631–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darfeuille-Michaud A, Boudeau J, Bulois P, Neut C, Glasser AL, Barnich N, et al. High prevalence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:412–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartley MG, Hudson MJ, Swarbrick ET, Hill MJ, Gent AE, Hellier MD, et al. The rectal mucosa-associated microflora in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:96–103. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-2-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bibiloni R, Mangold M, Madsen KL, Fedorak RN, Tannock GW. The bacteriology of biopsies differs between newly diagnosed, untreated, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1141–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swidsinski A, Weber J, Loening-Baucke V, Hale LP, Lochs H. Spatial organization and composition of the mucosal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3380–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3380-3389.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Medina M, Aldeguer X, Gonzalez-Huix F, Acero D, Garcia-Gil LJ. Abnormal microbiota composition in the ileocolonic mucosa of Crohn's disease patients as revealed by polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1136–45. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000235828.09305.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehman A, Lepage P, Nolte A, Hellmig S, Schreiber S, Ott SJ. Transcriptional activity of the dominant gut mucosal microbiota in chronic inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:1114–22. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.021170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker AW, Sanderson JD, Churcher C, Parkes GC, Hudspith BN, Rayment N, et al. High-throughput clone library analysis of the mucosa-associated microbiota reveals dysbiosis and differences between inflamed and non-inflamed regions of the intestine in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Wang C, Tang C, Li N, Li J. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of the microbiota in ulcerated and non-ulcerated regions in the patients with Crohn's disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloom SM, Bijanki VN, Nava GM, Sun L, Malvin NP, Donermeyer DL, et al. Commensal Bacteroides species induce colitis in host-genotype-specific fashion in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:390–403. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariat D, Firmesse O, Levenez F, Guimaraes V, Sokol H, Dore J, et al. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]