Abstract

Fabricating inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells (PSCs) on plastic substrates broadens their scope for implementation in real systems by imparting portability, conformability and allowing high-throughput production, which is necessary for lowering costs. Here we report a new route to prepare highly dispersed Zn2SnO4 (ZSO) nanoparticles at low-temperature (<100 °C) for the development of high-performance flexible PSCs. The introduction of the ZSO film significantly improves transmittance of flexible polyethylene naphthalate/indium-doped tin oxide (PEN/ITO)-coated substrate from ∼75 to ∼90% over the entire range of wavelengths. The best performing flexible PSC, based on the ZSO and CH3NH3PbI3 layer, exhibits steady-state power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 14.85% under AM 1.5G 100 mW·cm−2 illumination. This renders ZSO a promising candidate as electron-conducting electrode for the highly efficient flexible PSC applications.

There has been impressive progress in the development of perovskite solar cells in recent years, but the best performing systems tend to be fabricated on glass surfaces. Here, the authors present a cell built on a polymer substrate, allowing flexibility whilst maintaining high efficiency.

There has been impressive progress in the development of perovskite solar cells in recent years, but the best performing systems tend to be fabricated on glass surfaces. Here, the authors present a cell built on a polymer substrate, allowing flexibility whilst maintaining high efficiency.

Since the first application of organic–inorganic perovskite materials into solar cells in 2009 (ref. 1), tremendous progress has been made in this field. Recently, we have demonstrated the confirmed efficiencies exceeding 18% for small-sized devices2. Highly efficient perovskite solar cells (PSCs) with ignorable hysteresis mainly use mesoporous (mp)-TiO2 as the electron acceptor and hole barrier layer3,4,5, although several materials, including Al2O3 (ref. 6), ZrO2 (ref. 7) and SrTiO3 (ref. 8) and so on, have been applied as electrodes. The drawback with mp-TiO2 is that a high-temperature process (>400 °C) is required, which prevents the use of low-cost, lightweight and flexible plastic substrates as they are unstable at high temperatures. Hence, low-temperature processable metal oxides are required for the construction of industrial printing processes with high-throughput production lines, in order to achieve the associated potential reduction in manufacturing costs9,10. In addition, the use of plastic substrates can enable portable, conformable and lightweight solar cells linked with consumer electronics. However, the PCEs of flexible solar cells fabricated on plastic substrates have generally been very low in comparison with those of PSCs fabricated on rigid substrates.

The first PSC using low-temperature processed metal oxide on a flexible substrate was demonstrated with a very low PCE of 2.62% by Mathews's group using ZnO nanorods11. More recently, PCE of 10.2% was obtained using ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) deposited on polymer substrates, whereas low-temperature processed mp-TiO2 delivered solar cells with 8.4% efficiency12. Most recently, Jung et. al.13 reported an efficient flexible PSC exhibiting champion PCE of 12.2% using a metal oxide electron transport layer; however, they used a compact TiOx layer, deposited by atomic layer deposition, which is not solution processable. This state-of-the-art flexible PSC has provoked our interest in the use of other solution-processable metal oxide to further improve the performance. However, the synthesis of crystalline metal oxide NPs in solution requires mostly high temperature and high pressure. Furthermore, it will be important to prepare the particles which have capabilities to form a uniform and dense layer without additional steps, in particular at elevated temperature.

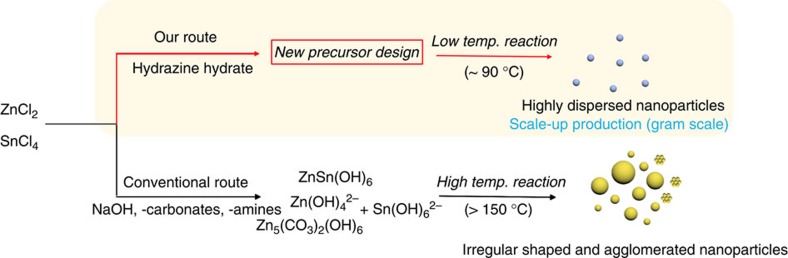

Zn2SnO4 (ZSO) is well known as a transport-conducting oxide for use in optoelectronic applications, due to its acceptable electrical and optical properties12. It is an n-type semiconductor with a small electron effective mass of 0.23 me and a high-electron Hall mobility of 10–30 cm2 Vs−1 (ref. 14). In addition, it has a wide optical band gap of 3.8 eV and a relatively low refractive index of ∼2.0 in the visible spectrum15,16. Furthermore, the conduction band edge position that is similar to that of TiO2 and ZnO makes it an excellent photoelectrode in emerging solar cell technologies, such as PSC, dye sensitized solar cell (DSSC) and organic photovoltaic (OPV)17,18,19. Finally, the most attractive attribute of crystalline ZSO is its chemical stability with respect to acid/base solution and polar organic solvents, for solution processing20,21. However, the ZSO ternary system is not easy to synthesize as highly dispersed NPs, and requires rather high temperatures (>200 oC) to crystallize, compared with binary oxide systems (that is, TiO2, ZnO and SnO2) because both Zn and Sn ions must be regulated during a synthetic reaction. Generally, the synthesis temperature of ZSO is considerably influenced by the type of zinc precursor complex19,22. In the conventional route, ZSO NPs are synthesized with a strong base, such as NaOH, via ZnSn(OH)6 intermediate phase. However, a high reaction temperature (>200 °C) is required for the transformation of ZnSn(OH)6 into crystalline ZSO23. Several groups have attempted to reduce the reaction temperature by controlling the Zn complex-precursors using -amine and -carbonate mineralizers, resulting in the formation of Zn(OH)42− and Zn5(CO3)2(OH)6 (refs 19, 22, 24). However, high temperatures (>150 °C) are still required for the dissociation/condensation process with Sn(OH)62−, inducing irregular shaped and agglomerated ZSO NPs.

Here, we report flexible PSCs comprised of a polyethylene naphthalate/indium-doped tin oxide (PEN/ITO) substrate, a low-temperature solution-processed ZSO layer, a CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite layer, a poly(triarylamine) hole conductor layer and Au as the electrode. Notably, the presence of the ZSO layer allowed superior transmittance in the visible regions, compared with bare flexible PEN/ITO substrate. This was due to an anti-reflection effect, attributable to the low refractive index of ∼1.37. A high PCE, exceeding 15%, with high-quantum efficiency was achieved. To the best of our knowledge, this PCE is the highest performance reported for flexible PSCs using metal oxide electrodes11,13,25.

Results

Synthesis of ZSO NPs via Zn-hydrazine complex precursor

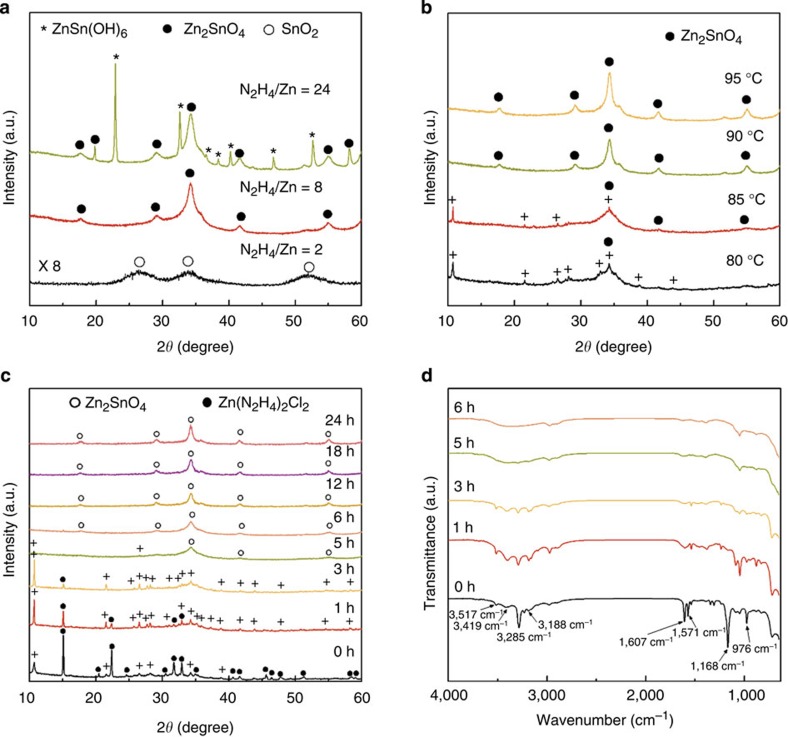

The strategy for synthesizing ZSO NPs below 100 °C is schematically depicted in Fig. 1. To synthesize highly dispersed, low-temperature ZSO NPs, the chemical reactions were carried out at 90 °C for 12 h, with various molar N2H4/Zn ratios. Figure 2a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of powders synthesized at 90 °C for 12 h, as a function of the different molar N2H4/Zn ratios (2, 8 and 24). At a low N2H4 concentration (N2H4/Zn=2), the only pure SnO2 phase is observed, whereas a pure ZSO phase with an inverse spinel structure (JCPDS 24-1470) is obtained at N2H4/Zn ratio=8. However, an excessive of N2H4, that is, N2H4/Zn=24, produces highly crystalline ZnSn(OH)6 as a secondary phase besides ZSO. It is well known that N2H4 can act, not only as a complexing agent but also as an OH supplier by a dissociation reaction during the reaction process26,27. Therefore, the variance in OH concentration caused by N2H4 can influence the formation of crystalline phases (SnO2, ZSO and ZnSn(OH)6). Figure 2b shows XRD patterns of the synthesized powders with different reaction temperature, from 80 to 95 oC, with N2H4/Zn=8. Unindexable peaks, denoted by ‘+', are observed with the ZSO phase at 80 and 85 oC, whereas all peaks are indexed by the ZSO phase at 90 and 95 oC. The unindexable peaks (to be discussed later) are related to new Zn–N–H–OH complexes in this process, indicating that a temperature below 90 oC is insufficient to drive the dissociation/condensation reaction of such complex precursor for the formation of ZSO crystal. Therefore, N2H4 concentration and reaction temperature are the key factors for synthesizing pure crystalline ZSO at a temperature below 100 °C. To understand the formation mechanism of ZSO crystals by N2H4 complexing below 100 °C, a time-dependent experiment was performed under certain conditions (N2H4/Zn=8 and 90 °C). Figure 2c shows the XRD patterns of powder prepared at different reaction times. According to the XRD traces, before heating (0 h), peaks (●) indexed for Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 (JCPDS 72-0620) are dominant compared with the unindexable peaks (+). However, the unindexable peaks predominate over the peaks corresponding to Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 after 1 h of heating. The peaks corresponding to Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 gradually disappear, whereas unindexble peaks, including the main peak at 10.7 °, further develop with an increase in the reaction time until 3 h, implying the transformation of Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 into new complex. After 5 h, most of the peaks based on the new complex disappear and pure ZSO crystal phases are observed with complete decomposition of the new complex. Also, the intensity of the ZSO peaks increase with an increase in the reaction time (12, 18 and 24 h), suggesting an increase in particle size (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our process was summarized in a flow chart (Supplementary Fig. 2). Based on these results, it can be concluded that the formation of new complex-precursors has a decisive effect on the low-temperature formation of ZSO crystals.

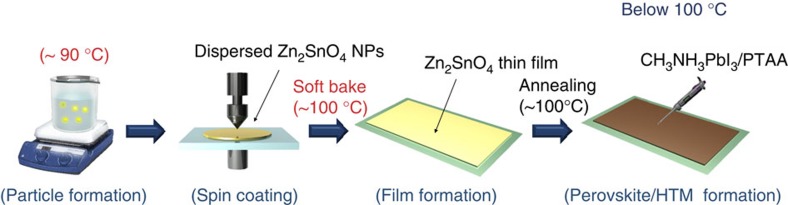

Figure 1. Synthetic procedure for ZSO.

Schematic illustration for the formation of highly dispersed ZSO NPs with a reaction temperature below 100 °C.

Figure 2. XRD and Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) of samples obtained with various reaction conditions.

Powder X-ray diffractograms (CuKα radiation) of (a) different N2H4/Zn ratios (90 °C, 12 h), (b) different reaction temperatures (N2H4/Zn=8, 12 h) and (c) different reaction times (90 °C, N2H4/Zn=8). (d) FT-IR spectra of samples synthesized at different reaction times (90 °C, N2H4/Zn=8). Unindexable peaks are denoted as (+).

Fourier transform infrared analysis was performed to reveal the possible composition of the new complex-precursors and to further study the formation mechanism (Fig. 2d). At 0 h, the characteristic peaks of Zn(N2H4)2Cl2, such as N–H stretching (3,188 and 3,285 cm−1), NH2 bending (1,571 and 1,607 cm−1), NH2 twisting (1,168 cm−1) vibration and N–N stretching (976 cm−1) vibration are observed and are accordant with the reported values28. In particular, the peak at 976 cm−1 appears when the N2H4 coordinates two metal ions in a bidentate bridging mode, which is strong evidence for the formation of a metal hydrazine complex29. Importantly, with an increase in reaction time up to 3 h at 90 °C, the N–N stretching (976 cm−1), the NH2 bending (1,571 and 1,607 cm−1) and the NH2 twisting (1,168 cm−1) peaks gradually disappear. Conversely, the N–H stretching peaks at 3,188 and 3,285 cm−1 remain, but with small shift, and the peaks at 3,418 and 3,516 cm−1 are much better pronounced. The peak at 3,418 cm−1 is due to stretching of the OH linked to the matrix, and the peak at 3,516 cm−1 is due to coordinated/adsorbed water molecules, respectively30. These results may imply decomposition of the zinc bishydrazine complex into a zinc ammine complex that includes OH- ions (Zn–N–H–OH). In addition, by energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis, we observe the reduction and removal of Cl- with the increase in reaction time from 0 to 3 h (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results indicate that new Zn–N–H–OH complex-phases are formed during the reaction, by decomposition of N2H4, removal of Cl− ions, and incorporation of OH− ions from initial Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 complex. As the reaction progresses over 6 h, all of the characteristic peaks for the Zn–N–H–OH complex disappear, suggesting the formation of a crystalline ZSO, which is in accordance with the XRD results.

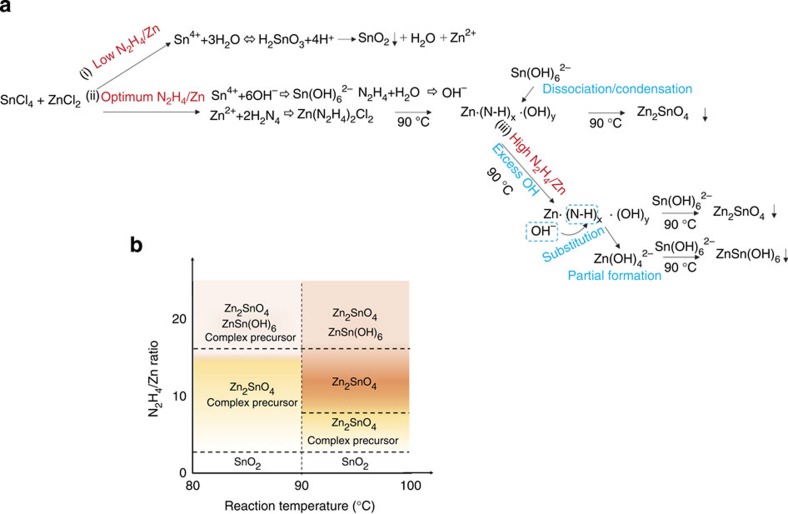

Based on the series of experiments described above, we propose a possible formation mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 3a, to rationalize the formation of ZSO NPs at temperatures below 100 °C. When the hydrazine concentration is low ((i) route: acidic condition), H2SnO3 is produced due to the strong hydrolysis effect of Sn4+, which can lead to the formation of SnO2, whereas Zn2+ ions remain in the solution and are washed away after the reaction23. On the other hand, an appropriate concentration of hydrazine ((ii) route: mild alkaline condition) prevents the hydrolysis reaction of Sn4+, and favour the formation of Sn(OH)62− rather than H2SnO3 (ref. 21), whereas the Zn2+ ion forms a Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 complex with hydrazine31,32. In metal-hydrazine systems, the metal/hydrazine ratio is an important factor for determining the composition of the hydrazine complex such as M(N2H4)1XCl2, M(N2H4)2XCl2 and M(NH3)XCl2 (refs 33, 34). In our case (N2H4/Zn=8), Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 is the dominant form initially (at 0 h), as it is more stable than other compositions. As the reaction progresses, the zinc ammine hydroxo complex, Zn–N–H–OH, is formed by the reaction of Zn(N2H4)2Cl2 with excess N2H4, and a continuous supply of OH- (ref. 35). Compared with other metal complexes, the metal ammine hydroxo complex requires a relatively low temperature (<100 °C) for the formation of the crystalline metal oxide. This is due to the low-energy kinetics of metal-ammine dissociation and the hydroxide condensation/dehydration reaction36,37. Therefore, we believe that Zn–N–H–OH complexes can lead to the formation of crystalline ZSO with Sn(OH)62-, even below 100 °C. However, an excess hydrazine ((iii) route: alkaline condition) leads to the formation of ZnSn(OH)6 as a secondary phase. The increased pH favours the substitution of N–H with OH- in the Zn–N–H–OH complex, resulting in the partial formation of Zn(OH)42- (ref. 38). In this case, ZnSn(OH)6 can be produced as a secondary phase, in which the transformation of ZnSn(OH)6 into ZSO requires a high temperature (>200 °C)23. As a result, both ZSO and ZnSn(OH)6 are formed during the 90 °C reaction. From these results and additional detailed experiments, we propose a rough formation map of ZSO, which outlines the effects of variations in temperature and N2H4/Zn ratio, for the process below 100 oC (Fig. 3b). As shown in the map, an N2H4/Zn ratio in the range of 8–24 at a temperature of around 90 °C, leads to a crystalline ZSO phase without secondary phases, which is the first demonstration of the synthesis of pure ZSO at a low temperature (<100 °C). This mild synthesis condition is comparable to that of binary oxides (TiO2 or ZnO), and can provide powerful competitiveness as an alternative to binary oxides for various device applications.

Figure 3. Formation mechanism of ZSO NPs.

(a) Schematic illustration of the formation mechanism of crystalline ZSO NPs via a low-temperature process below 100 °C. (b) Formation map of ZSO with different temperature and hydrazine/Zn ratio.

Deposition of ZSO thin layers onto substrates

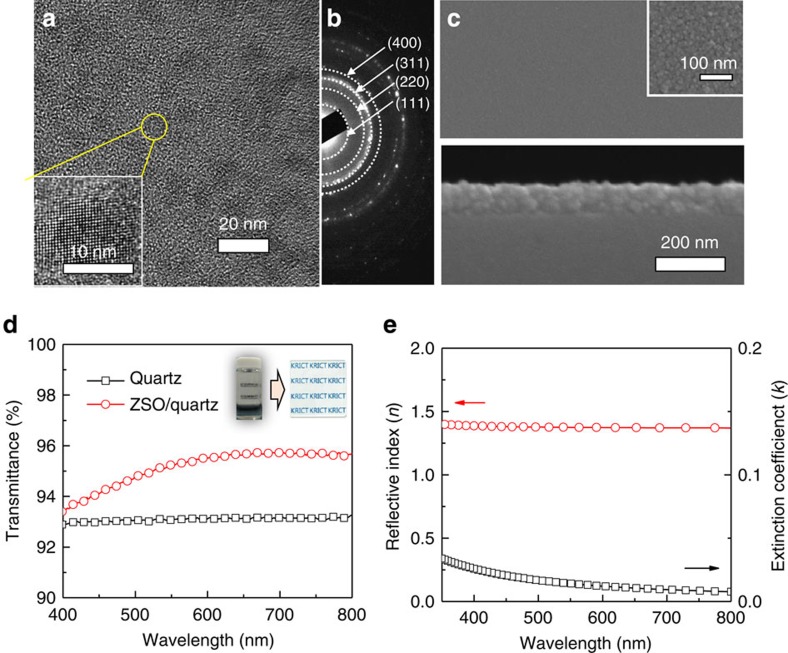

Figure 4a,b shows representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the ZSO NPs synthesized at 90 °C for 12 h. The TEM image exhibits highly dispersed and defined particles with a narrow size distribution (∼11 nm). The formation of uniform and dispersed NPs can be ascribed to the low reaction temperature and the formation of a stable precursor complex with hydrazine33. In addition, the high-resolution TEM image (inset in Fig. 4a) and the SAED patterns (Fig. 4b) are in agreement with the spinel structure of ZSO deduced from XRD patterns. Moreover, elemental mapping by energy dispersive spectroscopy indicates the homogeneous distribution of Zn and Sn elements in the NPs, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. For fabrication of high throughput and flexible optoelectronic applications, characterization of the low-temperature, solution-processed ZSO film is required. We deposited ZSO film on fused silica substrates by spin-coating and drying at 100 °C, using the resultant crystalline ZSO colloidal solution. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the ZSO film are shown in Fig. 4c. The plane image (Fig. 4c above) reveals that the surface exhibits crack-free, uniform morphology, with densely packed NPs (inset in Fig. 4c above). The atomic force microscopy analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5) indicates the resultant ZSO film has a flat surface with a root-mean-square roughness of 2.07 nm. Moreover, the entire substrate surface is uniformly covered by ZSO NPs with a thickness of ∼100 nm (Fig. 4c below). Figure 4d shows the optical transmission spectra of a ZSO film on quartz after several coating cycles. The transmittance of ZSO films is comparable to bare fused silica substrates over the entire wavelength region, regardless of their thickness (various coating cycles, Supplementary Fig. 6). The photograph (inset in Fig. 4d) shows that the ZSO film fabricated from the highly dispersed ZSO colloidal solution is highly transparent. The high transparency can be ascribed to the optical properties of the ZSO film. Figure 4e shows the refractive index (n) and extinction coefficient (k) spectra for ∼100-nm-thick ZSO film deposited on a silicon substrate measured using spectroscopic ellipsometry. The refractive index n is significantly small around 1.37 throughout the entire visible range compared with the reported value of 2.0 for ZSO film16. Because the refractive index for NP film has been reported to be determined by its crystallinity and porosity39,40, the ZSO film prepared from the low-temperature ZSO colloidal solution may possess low refractive index. In addition, the low extinction-coefficient value of nearly 0 in the visible region is in accordance with previously reported one16. The unique optical properties of the ZSO film such as lower refractive index (n∼1.37) than SiO2 glass (n∼1.5), wide band gap, and low-extinction coefficient (k) are causes of improved transmittance of the fused silica substrate, even after coating with the ZSO film. These results reveal that the low-temperature-synthesized ZSO NPs can facilitate the formation of highly transparent and uniform film on substrate without additional treatment.

Figure 4. Deposition and optical properties of ZSO film.

(a) TEM (inset: high-resolution TEM) and (b) SAED pattern of ZSO NPs synthesized at 90 °C for 12 h (N2H4/Zn=8). (c) Plane view and cross-sectional SEM image of ZSO thin film (inset in Fig. 4c: high-magnification SEM image). (d) transmittance spectra of ZSO films on fused silica substrate with four coating times (inset: the photograph of ZSO colloidal solution and the resultant ZSO film). (e) The reflective index (n) and the extinction coefficient (k) of low-temperature processed ZSO film.

Fabrication of ZSO-based flexible PSCs

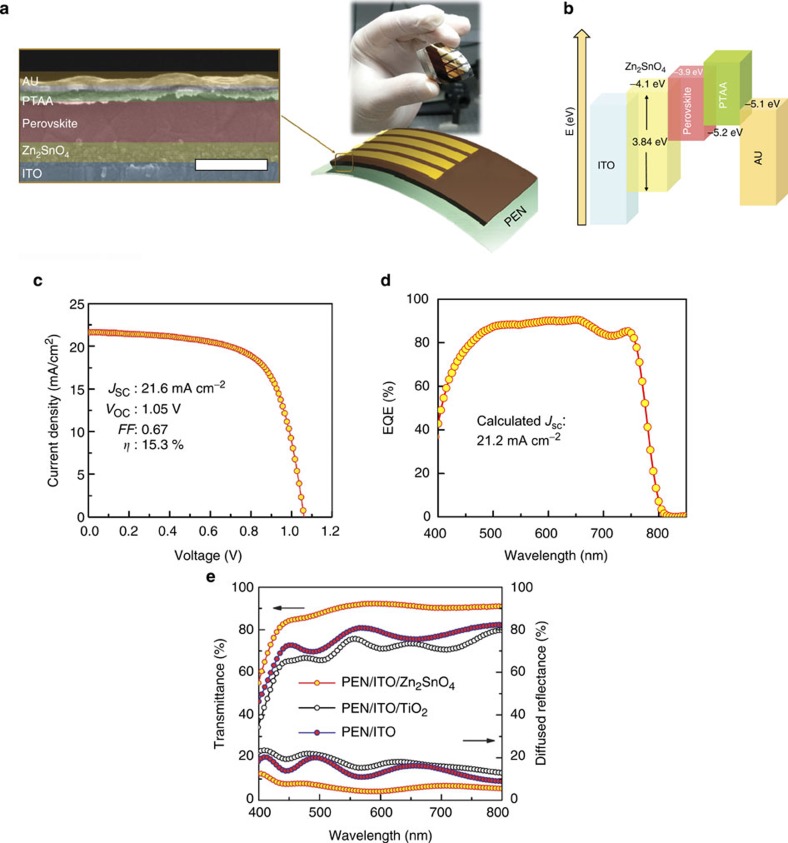

To demonstrate its viability for high throughput and flexible optoelectronic applications, ZSO film was employed, after four coating cycles, as an electron transport layer over PEN/ITO substrate. The ZSO film on ITO substrate, in common with those seen on quartz, has flat (root-mean-square: 3.76 nm) and uniform morphology with densely packed NPs (Supplementary Fig. 7). Figure 5 shows a series of processing steps from ZSO NPs formation to flexible solar cell fabrication. All steps require very simple techniques and low processing temperature below 100 °C. This is the first demonstration of low-temperature process for a ternary oxide electron transport layer to apply in PSCs, which can possibly provide an alternative to conventional TiO2- or ZnO-based PSCs. Figure 6a,b presents a colour-enhanced cross-sectional SEM image of the device architecture fabricated in this study and the corresponding energy level diagram of the device based on reported values17,41, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6a, two uniform layers, ZSO layer and a perovskite layer, are observed; the flat and homogeneous ZSO film with a thickness of 110±10 nm can lead to uniform perovskite film on the ITO/ZSO substrate by using pre-reported solvent-engineering technique3. Furthermore, the plane-view SEM image (Supplementary Fig. 8) showed that the perovskite layer on ZSO was deposited in dense and uniformly spread film with fine-grained morphology, which is similar with our previous report3. The fabricated flexible PSC is shown in the photograph in Fig. 6a. Figure 6b reveals that the energy level of ZSO is similar to that of TiO2, implying that it has an identical working mechanism as a TiO2-based PSCs. Figure 6c shows the photocurrent density–voltage (J–V) curve of the ZSO-based flexible PSC under simulated solar illumination (100 mW cm−2 air mass (AM) 1.5G). The J–V curve exhibits a short circuit current density (Jsc) of 21.6 mA cm−2, an open circuit voltage (Voc) of 1.05 V, and fill factor (FF) of 0.67, resulting in PCE (η) of 15.3% with steady-state PCE of 14.85%, which is comparable to the performance of ZSO-based PSC, prepared on ITO glass (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 1). ZSO-based PSC shows the hysteresis in the J–V curves measured with reverse and forward scan (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 2), although it is smaller than those of our TiO2-based planar device reported by us3. However, in contrast to TiO2-based planar PSCs reported by other groups4, the stabilized photocurrent density and PCE obtained from ZSO NPs-based planar PSC approaches the value measured by reverse mode (Supplementary Fig. 10). This result is consistent with that of mesosuperstructured solar cells4. We repeated the fabrication procedure to obtain a reliable and reproducible result. As can be seen in the histogram for the photovoltaic parameters collected from 60 independent devices (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 3), around 40% of the cells show PCE over 13% with the average PCE of 13.7%. In particular, the average Jsc and Voc exceed 20 mA cm−2 and 1 V, respectively, which is much greater than other flexible PSCs based on TiO2/ZnO/PEDOT:PSS. Furthermore, the flexible device shows a very broad external quantum efficiency (EQE) plateau over 80% between 460 and 755 nm, as shown in Fig. 6d. Integrating the product of the AM 1.5 G photon flux with the EQE spectrum yield a predicted Jsc of 21.2 mA cm−2, which agrees well with the measured value of 21.6 mA cm−2. This high EQE corresponding to a high Jsc for ZSO-based PSCs reveals that the ZSO film prepared at low-temperature produces excellent electron collecting and light harvesting ability within the device. The high performance (≥15%) of flexible PSCs is first demonstrated using the newly designed, solution-processed ZSO film, which is superior to the reported TiO2- and ZnO-based flexible PSCs13,25. The higher charge collecting ability might be due to the higher electron mobility of ZSO in nature than conventional TiO2 (refs 15, 18). In addition to the high mobility of ZSO, the lower refractive index (n∼1.4) of the ZSO film than TiO2 film (n∼2.5) leads to further light harvesting gain due to the anti-reflectance effect between ITO (n∼2.0) and ZSO or TiO2 layers. Figure 6e presents the transmittance and diffused reflectance spectra for bare PEN/ITO, PEN/ITO/TiO2 and PEN/ITO/ZSO substrate. Introduction of the ZSO film brings significant reduction of the reflectance over the entire wavelength region, resulting in improvement of transmittance from ∼75 to ∼90%. As ITO on PEN film has a lower refractive index than the ITO film on glass due to lower crystallinity by low-temperature processing, reflectance loss between ITO and TiO2 for flexible substrate can be larger than that of glass substrate42. The ZSO film overcomes the poor transmittance caused by the flexible substrate43, which can lead a comparable Jsc with that of a device based on glass substrate. As a result, superior electrical/optical properties of ZSO film can improve the Jsc for flexible PSCs. In addition, we performed mechanical bending tests over 300 cycles. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 13, the performance of the device retains over 95% of its initial efficiency even after 300 bending cycles.

Figure 5. Experimental procedure for PSCs.

Schematic illustration of the low-temperature process for fabricating flexible device with ZSO NPs.

Figure 6. Structure and performance of ZSO-based flexible perovskite solar cell.

(a) Cross-sectional SEM image and photograph of the ZSO-based flexible perovskite solar cell (scale bar, 500 nm). (b) Energy levels of the materials used in this study. (c) Photocurrent density–voltage (J–V) curve measured by reverse scan with 10 mV voltage steps and 40 ms delay times under AM 1.5 G illumination. (d) EQE spectrum of the ZSO-based flexible perovskite solar cell. (e) Transmittance and reflectance spectra of PEN/ITO/ZSO, PEN/ITO/TiO2 and PEN/ITO substrate. A dense TiO2 film was fabricated by TiO2 NPs obtained from a non-hydrolytic sol gel route9 (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Discussion

A well-dispersed crystalline ZSO colloidal solution was synthesized by the introduction of a Zn–N–H–OH complex derived from hydrazine via simple solution process at 90 oC. The flat and uniform ZSO films on flexible PEN/ITO substrate were also fabricated by a spin-coating method using the colloidal solution with drying at 100 oC. An n-type semiconducting ZSO film with wide band gap (3.8 eV) on flexible substrate has great potential for use in flexible optoelectronic devices. The resultant ZSO film shows a very low refractive index around 1.37 throughout the entire visible range, leading to improved transmittance of PEN/ITO substrate due to anti-reflection. The PSC using the highly transparent PEN/ITO/ZSO substrate showed high-quantum efficiency and a PCE of 15.3%, which is comparable to that of device based on rigid glass. This low-temperature synthetic method can provide a breakthrough for the fabrication of metal-oxide semiconductors on flexible substrate in advanced optoelectronic applications as a technology capable of high performance and large production.

Methods

Synthesis of ZSO NPs

All chemicals for the preparation of NPs were of regent grade and were used without further purification. ZnCl2 (12.8 mmol, Aldrich) and SnCl4·5H2O (6.4 mmol, Aldrich) were dissolved in deionized water (160 ml) under vigorous magnetic stirring. N2H4·H2O (N2H4 molar ratio/Zn=4/1, 8/1, 24/1) was then added to the reaction solution. White precipitates formed immediately, and this solution, including the precipitate, was heated on a hot plate at 90 °C for 12 h. The obtained products were thoroughly washed with deionized water and ethanol and were then dispersed in 2-methoxy ethanol, resulting in a colloidal solution.

Solar cell fabrication

A ZSO thin film was prepared by spin coating the colloidal dispersion of ZSO particles onto ITO-coated glass/PEN substrate at 3,000 r.p.m. for 30 s, followed by drying on a hot plate at 100 °C for 3 min. To control film thickness, the procedure was repeated four times. After baking at 100 °C for 1 h in air, the perovskite layer was deposited onto the resulting ZSO film by a consecutive two-step spin coating process at 1,000 and 5,000 r.p.m. for 10 and 20 s, respectively, from the mixture solution of methylammonium iodide (CH3NH3I) and PbI2. During the second spin coating step, the film was treated with toluene drop-casting, and then was dried on a hot plate at 100 °C for 10 min. The detailed preparation of the CH3NH3I has been described in previous work3. A solution of poly(triarylamine) (EM index, Mn=17,500 g mol−1, 15 mg in toluene 1.5 ml) was mixed with 15 μl of a solution of lithium bistrifluoromethanesulphonimidate (170 mg) in acetonitrile (1 ml) and 7.5 μl 4-tert-butylpyridine. The resulting solution was spin coated on the CH3NH3PbI3/ZSO thin film at 3,000 r.p.m. for 30 s. Finally, an Au counterelectrode was deposited by thermal evaporation.

Characterization

The crystal structure and phase of the materials were characterized using an XRD (New D8 Advance, Bruker) and SAED. The chemical composition of materials was investigated using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Nicolet 6,700, Thermo Scientific). The morphologies and microstructures were investigated by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, SU 70, Hitachi), transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2,100 F, JEOL) and atomic force microscopy (NanostationII, Surface Imaging Systems). The optical properties of samples were characterized using a ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (UV 2,550, Shimadzu). The EQE was measured using a power source (300 W xenon lamp, 66,920, Newport) with a monochromator (Cornerstone 260, Newport) and a multimeter (Keithley 2001). The J–V curves were measured using a solar simulator (Oriel Class A, 91,195 A, Newport) with a source meter (Keithley 2,420) at 100 mW cm−2, AM 1.5 G illumination, and a calibrated Si-reference cell certified by the NREL. The J–V curves were measured by reverse scan (forward bias (1.2 V) → short circuit (0 V)) or forward scan (short circuit (0 V) → forward bias (1.2 V)). The step voltage and the delay time were fixed at 10 mV and 40 ms, respectively. The J–V curves for all devices were measured by masking the active area with a metal mask 0.096 cm2 in area. Time-dependent current was measured with a potentiostat (PGSTAT302N, Autolab) under one sun illumination.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Shin, S. S. et al. High-performance flexible perovskite solar cells exploiting Zn2SnO4 prepared in solution below 100 °C. Nat. Commun. 6:7410 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8410 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-13 and Supplementary Tables 1-3

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Global Research Laboratory (GRL) Program, the Global Frontier R&D Program of the Center for Multiscale Energy System funded by the National Research Foundation in Korea, and by a grant from the KRICT 2020 Program for Future Technology of the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT), Republic of Korea. S.S.S. thanks Hye-Eun Nam, at Kaywon School of Art and Design for supporting graphic illustration, for her graphical assistance.

Footnotes

Author contributions S.S.S., W.S.Y. and S.I.S. conceived the experiments, data analysis and interpretation. S.S.S., J.S.K., J.H.P., W.M.S. and J.H.S. carried out the synthesis and characterization of Zn2SnO4 nanoparticles. W.S.Y., S.S.S. and N.J.J performed the fabrication of films and devices, device performance measurements and characterization. N.J.J. and W.S.Y. carried out the synthesis of materials for perovskites. The manuscript was mainly written and revised by S.S.S, J.H.N and S.I.S. The project was planned, directed and supervised by S.I.S. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Kojima A., Teshima K., Shirai Y. & Miyasaka T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon N. J. et al. Compositional engineering of perovskite materials for high-performance solar cells. Nature 517, 476–480 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon N. J. et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 13, 897–903 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith H. J. et al. Anomalous hysteresis in perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 1511–1515 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger E. et al. Hysteresis and transient behavior in current–voltage measurements of hybrid-perovskite absorber solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3690–3698 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. M., Teuscher J., Miyasaka T., Murakami T. N. & Snaith H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 338, 643–647 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D. et al. Using a two-step deposition technique to prepare perovskite (CH3NH3PbI3) for thin film solar cells based on ZrO2 and TiO2 mesostructures. RSC Adv. 3, 18762–18766 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Bera A. et al. Perovskite oxide SrTiO3 as an efficient electron transporter for hybrid perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 28494–28501 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. et al. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345, 542–546 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conings B. et al. An easy-to-fabricate low-temperature TiO2 electron collection layer for high efficiency planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. APL Mater. 2, 081505 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M. H. et al. Flexible, low-temperature, solution processed ZnO-based perovskite solid state solar cells. Chem. Commun. 49, 11089–11091 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo F. et al. Flexible perovskite photovoltaic modules and solar cells based on atomic layer deposited compact layers and UV-irradiated TiO2 scaffolds on plastic substrates. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, doi:10.1002/aenm.201401808 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. J. et al. Highly efficient and bending durable perovskite solar cells: toward a wearable power source. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 916–921 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Coutts T. J., Young D. L., Li X., Mulligan W. & Wu X. Search for improved transparent conducting oxides: a fundamental investigation of CdO, Cd2SnO4, and Zn2SnO4. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 18, 2646–2660 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. S. et al. Controlled interfacial electron dynamics in highly efficient Zn2SnO4-based dye-sensitized solar cells. ChemSusChem 7, 501–509 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D. L., Moutinho H., Yan Y. & Coutts T. J. Growth and characterization of radio frequency magnetron sputter-deposited zinc stannate, Zn2SnO4, thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 310–319 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Alpuche-Aviles M. A. & Wu Y. Photoelectrochemical study of the band structure of Zn2SnO4 prepared by the hydrothermal method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3216–3224 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh L. S. et al. Zn2SnO4-based photoelectrodes for organolead halide perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 22991–22994 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. W. et al. Synthesis and photovoltaic property of fine and uniform Zn2SnO4 nanoparticles. Nanoscale 4, 557–562 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çetinörgü E. & Goldsmith S. Chemical and thermal stability of the characteristics of filtered vacuum arc deposited ZnO, SnO2 and zinc stannate thin films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 40, 5220 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. et al. CdS/CdTe thin-film solar cell with a zinc stannate buffer layer. AIP Conf. Proc. 462, 37 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Fu X. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic properties of Zn2SnO4. J. Solid State Chem. 182, 517–524 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J. et al. Transformation process and photocatalytic activities of hydrothermally synthesized Zn2SnO4 nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 4159–4167 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai A., Carvalho D., Wilson K. & Lee M.-J. Properties of hydrothermally synthesized Zn2SnO4 nanoparticles using Na2CO3 as a novel mineralizer. Mater. Charact. 61, 873–881 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. & Kelly T. L. Perovskite solar cells with a planar heterojunction structure prepared using room-temperature solution processing techniques. Nat. Photon. 8, 133–138 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Heaton B. T., Jacob C. & Page P. Transition metal complexes containing hydrazine and substituted hydrazines. Coord. Chem. Rev. 154, 193–229 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Yang D., Yu G., Zhang H. & Yao K. A simple hydrothermal route for synthesizing SnO2 quantum dots. Nanotechnology 17, 2386 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sacconi L. & Sabatini A. The infra-red spectra of metal (II)-hydrazine complexes. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 25, 1389–1393 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya R., Yonemura M., Uehara A. & Kyuno E. Derivatographic studies on transition metal complexes. XIII. Thermal decomposition of [Ni (N2H4)6]X2 complexes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 47, 660–664 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Wypych F., Guadalupe Carbajal Arízaga G. & Ferreira da Costa Gardolinski J. E. Intercalation and functionalization of zinc hydroxide nitrate with mono-and dicarboxylic acids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 283, 130–138 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A., Braibanti A. & Bigliardi G. Chains of complexes in the crystal structure of bishydrazine zinc chloride. Acta Crystallogr. 16, 498–502 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Zhang W., Zou G., Yu W. & Qian Y. Precursor-induced hydrothermal synthesis of flowerlike cupped-end microrod bundles of ZnO. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 1361–1363 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. W. et al. Preparation of fine Ni powders from nickel hydrazine complex. Mater. Chem. Phys. 97, 371–378 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. Y. et al. A chemical route to large-scale preparation of spherical and monodisperse Ni powders. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88, 3020–3023 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z.-y., Chen Q.-y., Yin Z.-l. & Liu K. Predominance diagrams for Zn(II)–NH3–Cl−–H2O system. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 23, 832–840 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Meyers S. T. et al. Aqueous inorganic inks for low-temperature fabrication of ZnO TFTs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 17603–17609 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. H. et al. High-performance ZnO transistors processed via an aqueous carbon-free metal oxide precursor route at temperatures between 80–180° C. Adv. Mater. 25, 4340–4346 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Wang C.-L., Chen Y.-W. & Chen H.-L. Synthesis of hierarchy ZnO by a template-free method and its photocatalytic activity. Mater. Chem. Phys. 121, 1–5 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Rubner M. F. & Cohen R. E. All-nanoparticle thin-film coatings. Nano Lett. 6, 2305–2312 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod H. A. Thin-Film Optical Filters CRC (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Noh J. H., Im S. H., Heo J. H., Mandal T. N. & Seok S. I. Chemical management for colorful, efficient, and stable inorganic–organic hybrid nanostructured solar cells. Nano Lett. 13, 1764–1769 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-Y., Han Y.-K., Kim E.-R. & Suh K.-S. Two-layer hybrid anti-reflection film prepared on the plastic substrates. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2, 123–127 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Zardetto V., Brown T. M., Reale A. & Di Carlo A. Substrates for flexible electronics: A practical investigation on the electrical, film flexibility, optical, temperature, and solvent resistance properties. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys 49, 638–648 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-13 and Supplementary Tables 1-3