Abstract

Combined inhibition of complement and CD14 is known to attenuate bacterial-induced inflammation, but the dependency of the bacterial load on this effect is unknown. Thus, we investigated whether the effect of such combined inhibition on Escherichia coli- and Staphylococcus aureus-induced inflammation was preserved during increasing bacterial concentrations. Human whole blood was preincubated with anti-CD14, eculizumab (C5-inhibitor) or compstatin (C3-inhibitor), or combinations thereof. Then heat-inactivated bacteria were added at final concentrations of 5 × 104−1 × 108/ml (E. coli) or 5 × 107−4 × 108/ml (S. aureus). Inflammatory markers were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), multiplex technology and flow cytometry. Combined inhibition of complement and CD14 significantly (P < 0.05) reduced E. coli-induced interleukin (IL)-6 by 40–92% at all bacterial concentrations. IL-1β, IL-8 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α were significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited by 53–100%, and the effect was lost only at the highest bacterial concentration. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and MIP-1β were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced by 80–97% at the lowest bacterial concentration. Monocyte and granulocyte CD11b were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced by 63–91% at all bacterial doses. Lactoferrin was significantly (P < 0.05) attenuated to the level of background activity at the lowest bacterial concentration. Similar effects were observed for S. aureus, but the attenuation was, in general, less pronounced. Compared to E. coli, much higher concentrations of S. aureus were required to induce the same cytokine responses. This study demonstrates generally preserved effects of combined complement and CD14 inhibition on Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial-induced inflammation during escalating bacterial load. The implications of these findings for future therapy of sepsis are discussed.

Keywords: CD14, complement, inflammation, sepsis

Introduction

Despite modern treatment including up-to-date intensive care, sepsis still has high morbidity and mortality [1,2]. Massive research and several apparently promising clinical trials have not, so far, led to effective mediator-directed therapy for the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), potentially leading to severe sepsis and septic shock [3].

The cardinal trigger of the immune response which leads to SIRS is the recognition of conserved patterns of exogenous as well as endogenous ‘danger’ molecules by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of innate immunity [4,5]. Complement and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are central upstream sensor- and eventually effector-systems, thus triggering and maintaining the complex and widespread inflammatory response [6,7].

The complement system is a protein cascade with the main goal of defending the host against pathogens and maintaining homeostasis [8]. Complement is activated via the classical, lectin or alternative pathways. The pathways converge on the central complement factor C3, which is cleaved to C3a and C3b. Activation of the terminal pathway leading to the formation of the terminal C5b-9 complement complex (TCC) is triggered as C5 is cleaved to C5a and C5b [9]. C5a is a biologically highly potent anaphylatoxin associated with morbidity and mortality in sepsis [10].

The Toll-like receptor (TLR) family is a group of PRRs which recognize a wide variety of evolutionary conserved molecular structures [11]. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria are recognized by TLR-4, which is essential in inducing the Gram-negative inflammatory response [12]. Several danger molecules have been identified in Gram-positive bacteria, including various lipoproteins and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), and some of these danger molecules are recognized by TLR-2 [13–15]. CD14 is a promiscuous co-receptor for a number of TLRs and facilitates the signalling of both TLR-4 and TLR-2 [11,15]. Therefore, CD14 is an attractive target for upstream inhibition of TLR responses.

There is increasing evidence for close cross-talk between complement and TLRs, and recent research suggests possible synergistic anti-inflammatory effects when inhibiting both systems simultaneously [16]. Combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 has proved to be significantly more effective than single inhibition with either of these [17].

In clinical sepsis the bacterial load may increase rapidly, leading to an overwhelming inflammatory response. Although not equivalent to clinical sepsis, we have used an ex-vivo human whole blood model to simulate bacterial-induced inflammation. In previous studies, using one bacterial load, the combined inhibition of complement and CD14 has proved effective. In the present study we aimed to test whether the effect of combined inhibition would depend upon bacterial load. By incubating escalating loads of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in the human whole blood model, we examined to what extent the anti-inflammatory effect of the combined inhibition was preserved.

Materials and methods

Equipment and reagents

Endotoxin-free tubes and tips were purchased from Thermo Fischer Scientific NUNC (Roskilde, Denmark). Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with Ca2+ and Mg2+ and ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Lepirudin 2.5 mg/ml (Refludan, Pharmion, Windsor, UK) was used as an anti-coagulant.

Inhibitors

Azide-free mouse anti-human CD14 (clone 18D11; F(ab′)2 3118, lot1383), which neutralizes CD14, was purchased from Diatec Monoclonals AS (Oslo, Norway) and used in the E. coli experiments. The recombinant anti-human CD14 IgG2/4 antibody (r18D11) was used in the S. aureus experiments [18]. The complement C5 inhibitor, eculizumab (Soliris®) was obtained from Alexion Pharmaceuticals (Cheshire, CT, USA). The compstatin analogue Cp40 {dTyr-Ile-[Cys-Val-Trp(Me)-Gln-Asp-Trp-Sar-His-Arg-Cys]-mIle-NH2; 1.7 kDa}, a kind gift from Professor John Lambris, was produced by solid-phase peptide synthesis, as described previously [19].

Bacteria

Heat-inactivated E. coli strain LE392 (ATCC 33572) and S. aureus Cowan strain 1 (ATCC 12598) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

Ex-vivo whole blood model

The whole blood model has been described in detail previously [20]. In short, blood was drawn into 4-5 ml NUNC tubes containing the anti-coagulant lepirudin (50 µg/ml), which only blocks thrombin and does not interfere with the remaining inflammatory network. All the following experiments were performed with blood from six healthy donors. The different conditions described below were defined after careful pilot titration experiments to obtain optimal concentration and time intervals.

The E. coli experiments

Incubation of whole blood for final plasma analyses

The baseline sample (T0) was processed immediately after the blood was drawn and EDTA added to the whole blood. One tube was preincubated with PBS and served as the negative control. Four tubes were preincubated with PBS for 5 min at 37°C before adding E. coli to final concentrations of 5 × 104, 5 × 105, 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 bacteria/ml and served as positive controls. In the same manner, four tubes were preincubated with eculizumab only, four tubes with anti-CD14 only and four tubes with the combination of eculizumab and anti-CD14 before adding E. coli. All samples were incubated for a total of 4 h before adding EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mM. The tubes receiving 5 × 105, 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 bacteria/ml were used for measuring proinflammatory cytokines, whereas the tubes receiving 5 × 104, 5 × 105 and 5 × 106 bacteria/ml were used for measuring chemokines. The tubes receiving 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 bacteria/ml were used for measuring TCC. Experiments for analysis of granulocyte activation markers were conducted in the same manner as described above, with three modifications: instead of eculizumab, compstatin Cp40 was used for inhibiting complement, E. coli was added to final concentrations of 1 × 106, 3 × 106 and 9 × 106 bacteria/ml and all samples were incubated for a total of 1 h. We consistently used Cp40 (a C3-inhibitor) to study the release of granulocyte enzyme release instead of eculizumab, as this effect has been shown to be C3-dependent, in contrast to the other inflammatory readouts studied [21].

Incubation of whole blood for CD11b analysis

Immediately after drawing blood from the donor, the cells from a sample of the whole blood were fixed with 0.5% (v/v) paraformaldehyde in an equal volume for 4 min at 37°C to serve as a baseline (T0) sample. The subsequent bacterial activation of the whole blood was performed as described in the experiments for cytokine readout, with two modifications: E. coli was added to a final concentration of 4 × 106, 2 × 107 and 1 × 108 bacteria/ml and incubated for 15 min. Following 15 min incubation, the cells were fixed with 0.5% (v/v) paraformaldehyde in an equal volume for 4 min at 37°C, and then stained with anti-CD11b phycoerythrin (PE) and anti-CD14 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). The red cells were lysed and the samples washed twice using PBS with 0.1% Rinder albumin (300 g for 5 min at 4°C) before they were run on a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), with threshold on forward-scatter (FSC) to exclude debris. Monocytes were gated in a side-scatter/CD14 dot-plot, whereas granulocytes were gated in a forward-/side-scatter dot-plot. CD11b expression was measured as median fluorescence intensity (MFI).

The S. aureus experiments

Incubation of whole blood for final plasma analyses

The experiments were conducted in the same manner as described for E. coli, with two modifications: instead of E. coli, S. aureus was added to final concentrations of 5 × 107, 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 bacteria/ml, and all samples were incubated for a total of 2 h. In addition, samples containing 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 bacteria/ml were incubated for a total of 4 h for measuring TCC. Experiments for analysis of granulocyte activation markers were conducted in the same manner as described for E. coli, with one modification: instead of E. coli, S. aureus was added to final concentrations of 5 × 107, 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 bacteria/ml.

Incubation of whole blood for CD11b analysis

The experiments were conducted in the same manner as described for E. coli, with one modification: Instead of E. coli, S. aureus was added to final concentrations of 1 × 108, 2 × 108 and 4 × 108 bacteria/ml.

Multiplex analysis

Cytokines [tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-1β] were measured using a multiplex cytokine assay from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). The multiplex kit was used according to the instructions from the manufacturer.

Enzyme immunoassays

TCC

The soluble terminal C5b-9 complement complex (TCC) was measured in an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), as described previously, and later modified [22,23]. Briefly, the monoclonal antibody (mAb) aE11 reacting with a neoepitope exposed in C9 after incorporation in the C5b-9 complex was used as capture antibody. A biotinylated anti-C6 mAb (clone 9C4) was used as detection antibody. The standard was Stock Complement Standard no. 2 [24], which is normal human serum activated with zymosan and defined to contain 1000 complement arbitrary units (CAU)/ml. Zymosan-activated human serum was used as a positive control.

Granulocyte activation markers

The granulocyte activation markers myeloperoxidase and lactoferrin were quantified using commercial EIA kits from Hycult Biotech (Uden, the Netherlands). The analyses were performed in accordance with the instructions from the manufacturer.

Data presentation and statistics

All results are given as mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). GraphPad Prism version 5.04 (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (anova) with Dunnett's multiple comparison test was used to compare single and combined inhibition with positive controls. The background activation (negative control) was subtracted from the positive control and the intervention groups before calculating the percentage inhibition by the different inhibitors. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee and all blood donors gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

The E. coli experiments

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on proinflammatory cytokines

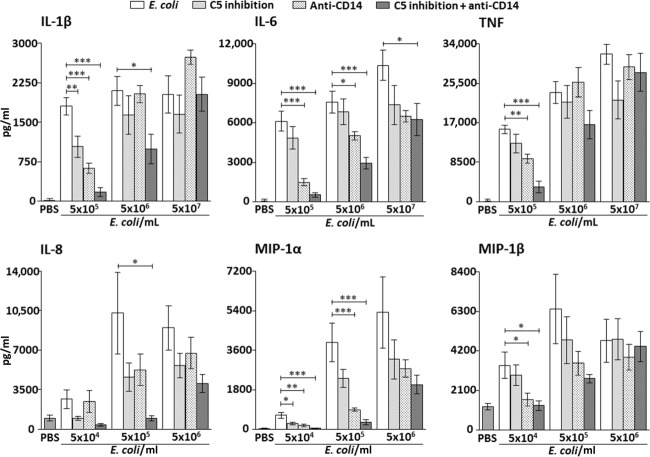

IL-1β

Single inhibition of both C5 and CD14 reduced IL-1β by 93% (P < 0.01) and 66% (P < 0.001), respectively, when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105 E. coli/ml (Fig. 1, upper left panel). No significant reduction of IL-1β was seen by single inhibition when using 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 E. coli/ml.

Fig. 1.

Effect of single and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on plasma concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (upper panels) and chemokines (lower panels) with increasing bacterial load in the Escherichia coli experiments. Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean. The background activation (negative control) was subtracted from the positive control and the intervention groups before calculating the percentage inhibition by the different inhibitors. Significances are between the positive control group (E. coli) and single and combined inhibition of C5 (eculizumab) and CD14. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 reduced IL-1β by 91% (P < 0.001) and 53% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105 and 5 × 106 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 1, upper left panel). No significant reduction of IL-1β was seen when using 5 × 107 E. coli/ml.

IL-6

Single inhibition of C5 had no significant effect on IL-6 at any of the bacterial concentrations, whereas single inhibition of CD14 reduced IL-6 by 76% (P < 0.001) and 34% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105 and 5 × 106 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 1, upper middle panel). No significant reduction of IL-6 was seen by single inhibition of CD14 when using 5 × 107 E. coli/ml.

Combined inhibition reduced IL-6 by 92% (P < 0.001), 62% (P < 0.001) and 40% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105, 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 1, upper middle panel).

TNF

Single inhibition of C5 had no significant effect on TNF at any of the bacterial concentrations, whereas single inhibition of CD14 reduced TNF by 41% (P < 0.01) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105 E. coli/ml (Fig. 1, upper right panel). No significant reduction of TNF was seen by single inhibition of CD14 when using 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 E. coli/ml.

Combined inhibition reduced TNF by 80% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105 E. coli/m. (Fig. 1, upper right panel). No significant reduction of TNF was seen when using 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 E. coli/ml.

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on chemokines

IL-8

Single inhibition of C5 and CD14 had no significant effect on IL-8 at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 reduced IL-8 by 100% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 105 E. coli/ml (Fig. 1, lower left panel). No significant reduction of IL-8 was seen when using 5 × 104 and 5 × 106 E. coli/ml.

MIP-1α

Single inhibition of C5 reduced MIP-1α by 60% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 104 E. coli/ml, whereas no significant reduction was seen when using higher concentrations of E. coli (Fig. 1, lower middle panel).

Single inhibition of CD14 reduced MIP-1α by 78% (P < 0.01) and 78% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 104 and 5 × 105 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 1, lower middle panel). No significant reduction of MIP-1α was seen by single CD14 inhibition when using and 5 × 106 E. coli/ml.

Combined inhibition reduced MIP-1α by 97% (P < 0.001) and 93% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 104 and 5 × 105 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 1, lower middle panel). No significant reduction of MIP-1α was seen when using 5 × 106 E. coli/ml.

MIP-1β

Single inhibition of C5 had no significant effect on MIP-1β at any of the bacterial concentrations, whereas single inhibition of CD14 reduced MIP-1β by 82% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 104 E. coli/ml (Fig. 1, lower right panel). No significant reduction of MIP-1β was seen by single CD14 inhibition when using 5 × 105 and 5 × 106 E. coli/ml.

Combined inhibition reduced MIP-1β by 97% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 104 E. coli/ml (Fig. 1, lower right panel). No significant reduction of MIP-1β was seen when using 5 × 105 and 5 × 106 E. coli/ml.

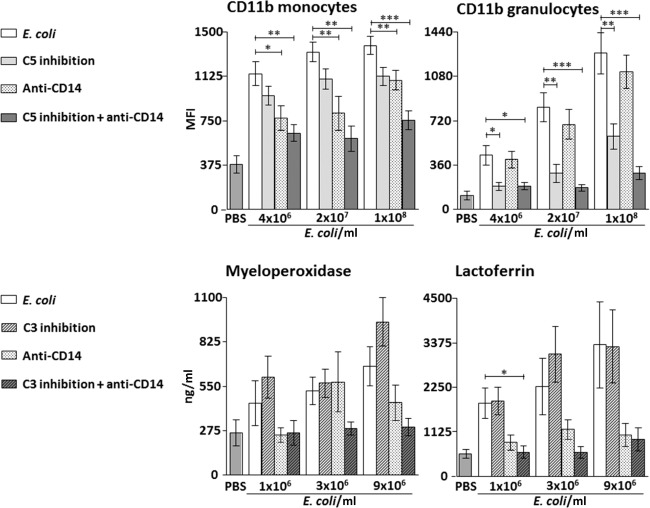

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on the expression of CD11b

Monocytes

Single inhibition of C5 had no significant effect on CD11b expression at any of the bacterial concentrations, whereas single inhibition of CD14 reduced CD11b expression by 49% (P < 0.05), 55% (P < 0.01) and 29% (P < 0.01) when whole blood was incubated with 4 × 106, 2 × 107 and 1 × 108 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 2, upper left panel).

Fig. 2.

Effect of single and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on CD11b expression on monocytes and granulocytes in whole blood (upper panels) and plasma concentrations of granulocyte enzyme release (lower panels) with increasing bacterial load in the Escherichia coli experiments. Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean. The background activation (negative control) was subtracted from the positive control and the intervention groups before calculating the percentage inhibition by the different inhibitors. Significances are between the positive control group (E. coli) and single and combined inhibition of either C5 (eculizumab in the CD11b experiments) and CD14 or C3 (compstatin in the granulocyte enzyme release experiments) and CD14. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 reduced CD11b expression by 66% (P < 0.01), 77% (P < 0.01) and 63% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 4 × 106, 2 × 107 and 1 × 108 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 2, upper left panel).

Granulocytes

Single inhibition of C5 reduced CD11b expression by 77% (P < 0.05), 75% (P < 0.01) and 59% (P < 0.01) when whole blood was incubated with 4 × 106, 2 × 107 and 1 × 108 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 2, upper right panel). Single inhibition of CD14 had no significant effect on CD11b expression at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition reduced CD11b expression by 77% (P < 0.05), 91% (P < 0.001) and 84% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 4 × 106, 2 × 107 and 1 × 108 E. coli/ml, respectively (Fig. 2, upper right panel).

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 on granulocyte enzyme release

We used a C3 inhibitor to study the release of granulocyte enzyme release, as this effect was shown to be C3-dependent, in contrast to the other inflammatory readouts studied, which were mainly C5-dependent [21].

Myeloperoxidase

Single and combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 had no significant effect on myeloperoxidase at any of the bacterial concentrations (Fig. 2, lower left panel).

Lactoferrin

Single inhibition of C3 and CD14 had no significant effect on lactoferrin at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 reduced the release of lactoferrin to the level of background activity when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 106 E. coli/ml (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2, lower right panel).

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on TCC concentration

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 and single inhibition of C5, reduced the formation of TCC by 98–99% (P < 0.001) and 99% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 106 and 5 × 107 E. coli/ml, respectively (Table 1), confirming that C5 inhibition was efficient over the whole range of bacterial concentrations. As expected, no reduction of TCC was seen with selective inhibition of CD14 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of complement C5 inhibition (eculizumab) and CD14 inhibition on the concentration of the terminal complement complex (TCC)

| Bacteria (per ml) | Positive control (CAU)* | Anti-CD14 (%)† | C5 inhibition (%)†‡ | C5 inhibition and anti-CD14 (%)†‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli 5 × 106 | 31 | 0 | 98 | 98 |

| E. coli 5 × 107 | 116 | 19 | 100 | 100 |

| S. aureus 1 × 108 | 76 | 21 | 96 | 99 |

| S. aureus 2 × 108 | 171 | 7.6 | 100 | 100 |

TCC measured as complement arbitrary units (CAU)

Reduction compared to positive control

All results P < 0·05. E. coli = Escherichia coli; S. aureus = Staphylococcus aureus.

Taken together, these data indicate that the effect of combined inhibition of complement and CD14 in general is well preserved by increasing doses of E. coli, although with some reduced effect on cytokines and chemokines in the highest bacterial concentration.

The S. aureus experiments

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on proinflammatory cytokines

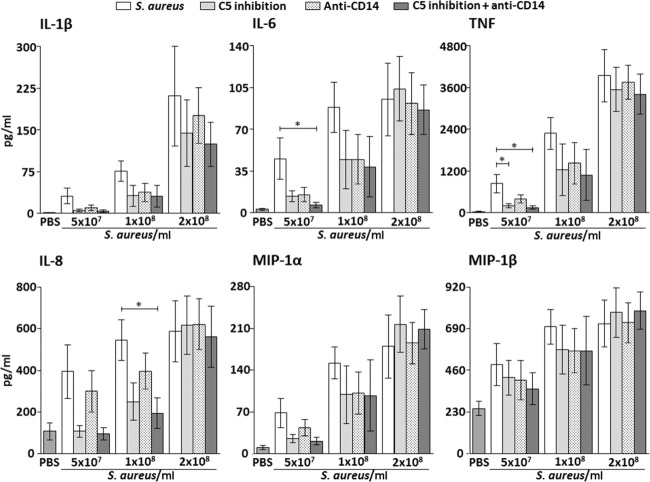

IL-1β

Single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 had no significant effect on IL-1β at any of the bacterial concentrations (Fig. 3, upper left panel).

Fig. 3.

Effect of single and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on plasma concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (upper panels) and chemokines (lower panels) with increasing bacterial load in the Staphylococcus aureus experiments. Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean. The background activation (negative control) was subtracted from the positive control and the intervention groups before calculating the percentage inhibition by the different inhibitors. Significances are between the positive control group (S. aureus) and single and combined inhibition of C5 (eculizumab) and CD14. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

IL-6

Single inhibition of C5 and CD14 had no significant effect on IL-1β at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition reduced IL-6 by 93% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 107 S. aureus/ml (Fig. 3, upper middle panel). No significant reduction of IL-6 was seen when using 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 S. aureus/ml.

TNF

Single inhibition of C5 reduced TNF significantly by 79% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 107 S. aureus/ml (Fig. 3, upper right panel). No significant reduction of TNF was seen when using 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 S. aureus/ml. Single inhibition of CD14 had no significant effect on TNF at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition reduced TNF by 86% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 5 × 107 S. aureus/ml (Fig. 3, upper right panel). No significant reduction of TNF was seen when using 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 S. aureus/ml.

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on chemokines

IL-8

Single inhibition of C5 and CD14 had no significant effect on IL-1β at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 reduced IL-8 by 80% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 108 S. aureus/ml (Fig. 3, lower left panel). No significant reduction of IL-8 was seen when using 5 × 107 and 2 × 108 S. aureus/ml.

MIP-1α

Single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 had no significant effect on MIP-1α at any of the bacterial concentrations (Fig. 3, lower middle panel).

MIP-1β

Single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 had no significant effect on MIP-1β at any of the bacterial concentrations (Fig. 3, lower right panel).

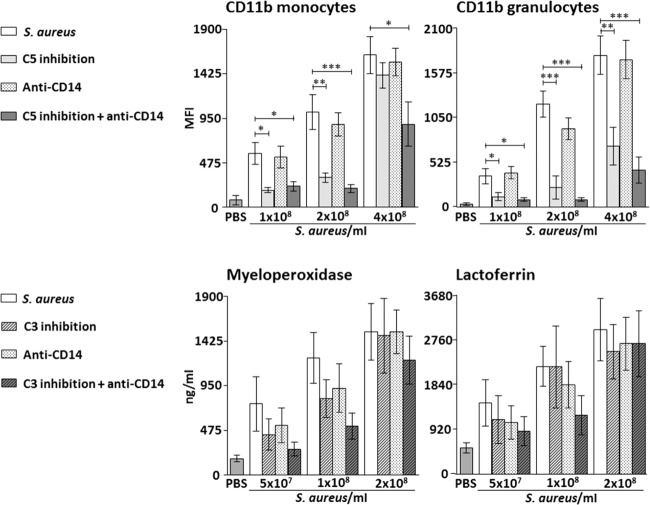

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on CD11b expression

Monocytes

Single inhibition of C5 reduced CD11b expression by 79% (P < 0.05) and 74% (P < 0.01) when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 S. aureus/ml, respectively (Fig. 4, upper left panel). No significant reduction of CD11b expression was seen when using 4 × 108 S. aureus/ml. Single inhibition of CD14 had no significant effect on CD11b expression at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Fig. 4.

Effect of single and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on CD11b expression on monocytes and granulocytes in whole blood (upper panels) and plasma concentrations of granulocyte enzyme release (lower panels) with increasing bacterial load in the Staphylococcus aureus experiments. Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean. The background activation (negative control) was subtracted from the positive control and the intervention groups before calculating the percentage inhibition by the different inhibitors. Significances are between the positive control group (S. aureus) and single and combined inhibition of either C5 (eculizumab in the CD11b experiments) and CD14 or C3 (compstatin in the granulocyte enzyme release experiments) and CD14. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 reduced CD11b expression by 70% (P < 0.05), 87% (P < 0.001) and 48% (P < 0.05) when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 108, 2 × 108 and 4 × 108 S. aureus/ml, respectively (Fig. 4, upper left panel).

Granulocytes

Single inhibition of C5 reduced CD11b expression by 73% (P < 0.05), 83% (P < 0.001) and 61% (P < 0.01) when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 108, 2 × 108 and 4 × 108 S. aureus/ml, respectively (Fig. 4, upper right panel). Single inhibition of CD14 had no significant effect on CD11b expression at any of the bacterial concentrations.

Combined inhibition reduced CD11b expression by 83% (P < 0.05), 95% (P < 0.001) and 77% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 108, 2 × 108 and 4 × 108 S. aureus/ml, respectively (Fig. 4, upper right panel).

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 on granulocyte enzyme release

We used a C3 inhibitor to study the release of granulocyte enzyme release, as this effect was shown to be C3-dependent, in contrast to the other inflammatory readouts studied, which were mainly C5-dependent [21].

Myeloperoxidase

Single and combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 had no significant effect on myeloperoxidase at any of the bacterial concentrations (Fig. 4, lower left panel).

Lactoferrin

Single and combined inhibition of C3 and CD14 had no significant effect on lactoferrin release at any of the bacterial concentrations (Fig. 4, lower right panel).

Effect of bacterial load on single and combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 on TCC concentration

Combined inhibition of C5 and CD14 and single inhibition of C5 reduced the formation of TCC by 98–99% (P < 0.05) and 99% (P < 0.001) when whole blood was incubated with 1 × 108 and 2 × 108 S. aureus/ml, respectively (Table 1), confirming that C5 inhibition was efficient over the whole range of bacterial concentrations. As expected, no reduction in TCC formation was seen with single inhibition of CD14.

Taken together, these data indicate that the preserved inhibitory effect of combined inhibition of complement and CD14 seen by increasing doses of the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus was less pronounced compared to what was found with the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli.

Discussion

The results of this study consistently show a relation between the increased bacterial load and the inflammatory response induced by E. coli and S. aureus. The findings correspond well with the clinical setting in which an increased level of cytokines is correlated with the severity of sepsis [25]. Notably, combined inhibition of complement and CD14 efficiently bacterial-induced inflammation attenuated over a broad range of bacterial concentrations. This effect was preserved quantitatively for most of the inflammatory mediators, although fewer significant results were observed for S. aureus compared with E. coli, and slightly lesser effects were seen for some of the proinflammatory cytokines at the highest bacterial concentration. The latter result is consistent with previous data on Neisseria meningitides [26]. Evidence suggests that high bacterial doses lead to a ‘point of no-return’ after which the inflammatory cascade cannot be affected by treatment [27].

Taking a ‘point of no return’ into consideration, the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs must be performed at an early stage, or perhaps even before the onset of sepsis in patients at high risk. As the microorganism is seldom known in early stages of clinical sepsis, we showed equally importantly that the combined inhibition was effective in reducing Gram-negative and -positive induced inflammation. However, compared to E. coli, much higher concentrations of S. aureus were required to induce the same inflammatory responses; the E. coli-induced inflammatory responses, especially chemokine responses and granulocyte enzyme release, were also attenuated more efficiently by the combined inhibition of complement and CD14.

The inflammatory response in Gram-positive sepsis is more complement-driven compared to the Gram-negative response, which is largely LPS-dependent and therefore more TLR-4-driven [28]. Although both complement and CD14 play vital roles mediating E. coli- as well as S. aureus-induced inflammation, it is uncertain whether the anti-CD14 effects observed on the S. aureus-induced responses reflect the involvement of TLR-2, TLR-9 or other TLRs [21,29]. The bacteria causing the infection are most often unknown at the time sepsis develops [30], and quite often the infecting microbe remains unknown. A treatment with combined inhibition of complement and CD14 is meant for early attenuation of the inflammatory response, before the cytokine storm emerges. Thus, from a clinical perspective, the combined approach therefore seems sensible, provided that proper antibiotic therapy is given. Furthermore, no single downstream anti-inflammatory treatment has been able to achieve increased survival in sepsis [31], whereas a caecal ligation and puncture-induced polymicrobial sepsis study in mice clearly showed increased survival in the group receiving combined inhibition [32]. The anti-inflammatory effects observed in the current study are thus linked to in-vivo effects, strengthening possible clinical implications by the combined inhibition.

The proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines included in the present study were selected based on their implication in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Plasma TNF, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 are important mediators of the inflammatory response in SIRS and sepsis and correlate partially with mortality and severity in septic patients [33–35]. However, several large clinical trials show that increased survival has not been achieved by targeting these cytokines selectively [36–38]. By targeting upstream recognition molecules of innate immunity, i.e. complement and CD14, we observed a significant concurrent reduction of all four cytokines in escalating bacterial-induced inflammation, implicating the benefits of upstream as opposed to downstream single agent anti-inflammatory treatments, even in relatively high bacterial concentrations. Interestingly, the release of IL-6 was inhibited significantly even at the highest concentration of E. coli. The inhibitory effect was still significant for IL-1β, IL-8 and MIP-1α at bacterial concentrations close to the highest dose. For S. aureus, less statistically significant effects were observed compared with E. coli, corresponding with a greater variation in the inflammatory response to the Gram-positive bacterium.

For a long time, C5a has been reported to induce IL-8 [39], which may explain the relative complement-dependent IL-8 release observed in the current study. IL-8 is one of the major mediators of the inflammatory response in sepsis with the main function to induce chemotaxis of neutrophils to the site of inflammation [25]. As the levels of IL-8 correlate with mortality in septic patients [33], the use of complement inhibition in sepsis is thus logical.

E. coli-induced surface expression of CD11b on granulocytes was reduced significantly to background levels by the combined inhibition even at the highest bacterial concentration. The release of myeloperoxidase was not changed significantly, whereas combined inhibition reduced lactoferrin significantly at the lower dose. In the presence of Gram-positive bacteria, however, this leucocyte inflammatory response was gradually less affected by combined inhibition as the bacterial load increased. Interestingly, E. coli-induced granulocyte CD11b expression was essentially complement-dependent, whereas for monocytes it was mainly CD14-dependent. In contrast, when activating whole blood with S. aureus, CD11b expression seemed to be complement-dependent for both subsets of leucocytes. These results are in line with previous studies and the concept of cross-talk between complement and TLRs [21,40].

In conclusion, this study showed significant broad anti-inflammatory effects by the combined inhibition of complement and CD14 by increasing Gram-negative as well as Gram-positive bacteria to high concentrations. A ‘point of no return’ in the inflammatory response emerges at last, underscoring the relevance of applying such treatment at an early stage of the syndrome. The results of the present study strengthen the hypothesis that the combined inhibition of complement and CD14 may become a future mediator-directed therapy in sepsis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported financially by The Research Council of Norway, The Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Disease, The Northern Norway Regional Health Authority, The Southern and Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, The Odd Fellow Foundation and the European Community's Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement no. 602699 (DIREKT).

Disclosure

All authors declare that they have no competing financial or other interest in relation to their work.

References

- 1.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, et al. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007) Chest. 2011;140:1223–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The surviving sepsis campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intens Care Med. 2010;36:222–31. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1738-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams SC. After Xigris, researchers look to new targets to combat sepsis. Nat Med. 2012;18:1001. doi: 10.1038/nm0712-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–37. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–26. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohl J. The role of complement in danger sensing and transmission. Immunol Res. 2006;34:157–76. doi: 10.1385/IR:34:2:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–97. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarma JV, Ward PA. The complement system. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:227–35. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward PA. The harmful role of c5a on innate immunity in sepsis. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:439–45. doi: 10.1159/000317194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CC, Avalos AM, Ploegh HL. Accessory molecules for Toll-like receptors and their function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:168–79. doi: 10.1038/nri3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–8. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroder NW, Morath S, Alexander C, et al. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus activates immune cells via Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), and CD14, whereas TLR-4 and MD-2 are not involved. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15587–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietrocola G, Arciola CR, Rindi S, et al. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in innate immune defense against Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34:799–810. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsen NJ, Deininger S, Nonstad U, et al. Cellular trafficking of lipoteichoic acid and Toll-like receptor 2 in relation to signaling: role of CD14 and CD36. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:280–91. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajishengallis G, Lambris JD. Crosstalk pathways between Toll-like receptors and the complement system. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egge KH, Thorgersen EB, Lindstad JK, et al. Post challenge inhibition of C3 and CD14 attenuates Escherichia coli-induced inflammation in human whole blood. Innate Immun. 2014;20:68–77. doi: 10.1177/1753425913482993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau C, Gunnarsen KS, Hoydahl LS, et al. Chimeric anti-CD14 IGG2/4 Hybrid antibodies for therapeutic intervention in pig and human models of inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;191:4769–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu H, Ricklin D, Bai H, et al. New analogs of the clinical complement inhibitor compstatin with subnanomolar affinity and enhanced pharmacokinetic properties. Immunobiology. 2013;218:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mollnes TE, Brekke OL, Fung M, et al. Essential role of the C5a receptor in E. coli-induced oxidative burst and phagocytosis revealed by a novel lepirudin-based human whole blood model of inflammation. Blood. 2002;100:1869–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lappegard KT, Christiansen D, Pharo A, et al. Human genetic deficiencies reveal the roles of complement in the inflammatory network: lessons from nature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15861–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903613106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mollnes TE, Lea T, Froland SS, Harboe M. Quantification of the terminal complement complex in human plasma by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on monoclonal antibodies against a neoantigen of the complex. Scand J Immunol. 1985;22:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1985.tb01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mollnes TE, Redl H, Hogasen K, et al. Complement activation in septic baboons detected by neoepitope-specific assays for C3b/iC3b/C3c, C5a and the terminal C5b-9 complement complex (TCC) Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergseth G, Ludviksen JK, Kirschfink M, Giclas PC, Nilsson B, Mollnes TE. An international serum standard for application in assays to detect human complement activation products. Mol Immunol. 2013;56:232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.05.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhry H, Zhou J, Zhong Y, et al. Role of cytokines as a double-edged sword in sepsis. In Vivo. 2013;27:669–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellerud BC, Stenvik J, Espevik T, Lambris JD, Mollnes TE, Brandtzaeg P. Stages of meningococcal sepsis simulated in vitro, with emphasis on complement and Toll-like receptor activation. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4183–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00195-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opal SM. Endotoxins and other sepsis triggers. Contrib Nephrol. 2010;167:14–24. doi: 10.1159/000315915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skjeflo EW, Christiansen D, Espevik T, Nielsen EW, Mollnes TE. Combined inhibition of complement and CD14 efficiently attenuated the inflammatory response induced by Staphylococcus aureus in a human whole blood model. J Immunol. 2014;192:2857–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumann CL, Aspalter IM, Sharif O, et al. CD14 is a coreceptor of Toll-like receptors 7 and 9. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2689–701. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoneking LR, Patanwala AE, Winkler JP, et al. Would earlier microbe identification alter antibiotic therapy in bacteremic emergency department patients? J Emerg Med. 2013;44:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remick DG. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1435–44. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huber-Lang M, Barratt-Due A, Pischke SE, et al. Double blockade of CD14 and complement C5 abolishes the cytokine storm and improves morbidity and survival in polymicrobial sepsis in mice. J Immunol. 2014;192:5324–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mera S, Tatulescu D, Cismaru C, et al. Multiplex cytokine profiling in patients with sepsis. APMIS. 2011;119:155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu HP, Chen CK, Chung K, et al. Serial cytokine levels in patients with severe sepsis. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:385–93. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cinel I, Opal SM. Molecular biology of inflammation and sepsis: a primer. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:291–304. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819267fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abraham E, Laterre PF, Garbino J, et al. Lenercept (p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein) in severe sepsis and early septic shock: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial with 1,342 patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:503–10. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher CJ, Jr, Dhainaut JF, Opal SM, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phase III rhIL-1ra Sepsis Syndrome Study Group. JAMA. 1994;271:1836–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opal SM, Fisher CJ, Jr, Dhainaut JF, et al. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. The Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Sepsis Investigator Group. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1115–24. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ember JA, Sanderson SD, Hugli TE, Morgan EL. Induction of interleukin-8 synthesis from monocytes by human C5a anaphylatoxin. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:393–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song WC. Crosstalk between complement and toll-like receptors. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:174–82. doi: 10.1177/0192623311428478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]