Abstract

Thirteen common susceptibility loci have been reproducibly associated with cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM). We report the results of an international 2-stage meta-analysis of CMM genome-wide association studies (GWAS). This meta-analysis combines 11 GWAS (5 previously unpublished) and a further three stage 2 data sets, totaling 15,990 CMM cases and 26,409 controls. Five loci not previously associated with CMM risk reached genome-wide significance (P < 5×10–8), as did two previously-reported but un-replicated loci and all thirteen established loci. Novel SNPs fall within putative melanocyte regulatory elements, and bioinformatic and expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) data highlight candidate genes including one involved in telomere biology.

Cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) primarily occurs in fair-skinned individuals; the major host risk factors for CMM include pigmentation phenotypes1-4, the number of melanocytic nevi5,6 and a family history of melanoma7.

Six population-based genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of CMM have been published8-13 identifying 12 regions that reach genome-wide significance. Some of these regions were already established melanoma risk loci, for example through candidate gene studies14 (for review see15). A 13th region in 1q42.12, tagged by rs3219090 in PARP1, that was borderline in the initial publication (P = 9.3 × 10–8)12 was confirmed as genome-wide significant by a recent study (P = 1.03 × 10–8)16. As might be expected for common variants influencing CMM risk many of these loci contain genes that are implicated in one of the two well-established heritable risk phenotypes for melanoma, pigmentation (SLC45A2, TYR, MC1R and ASIP) and nevus count (CDKN2A/MTAP, PLA2G6 and TERT) (Supplementary Table 1)17. The presence of DNA repair genes such as PARP1 and ATM at two loci suggests a role for DNA maintenance pathways, leaving four loci where the functional mechanism is less clear (ARNT/SETDB1, CASP8, FTO and MX2).

Of particular interest is TERT, which is involved in telomere maintenance; SNPs in this region have been associated with a variety of cancers11,18-22. Further, ATM and PARP1's DNA repair functions extend to telomere maintenance and response to telomere damage23,24. Longer telomeres have been associated with higher nevus counts and it has been proposed that longer telomeres delay the onset of cell senescence, allowing further time for mutations leading to malignancy to occur20,25. There is evidence that longer telomeres increase melanoma risk20,26,27 and that other telomere-related genes are likely involved in the etiology of melanoma, but none of these loci has yet reached genome-wide significance (or even P < 10–6)28.

In addition, two independent SNPs at 11q13.3, near CCND1, and 15q13.1, adjacent to the pigmentation gene OCA2, have been associated previously with melanoma, but did not meet the strict requirements for genome-wide significance, either not reaching P = 5 × 10–8 in the initial report, or not replicating in additional studies10,11,29. This meta-analysis has resolved the status of these two loci, as well as identified novel melanoma susceptibility loci.

Results and Discussion

We conducted a two-stage genome-wide meta-analysis. Stage one consisted of 11 GWAS totaling 12,874 cases and 23,203 controls from Europe, Australia and the USA; this includes all six published CMM GWAS and five unpublished ones (Supplementary Table 2). In Stage two we genotyped 3,116 CMM cases and 3,206 controls from three additional datasets (consisting of 1,692 cases and 1,592 controls from Cambridge, UK, 639 cases and 823 controls from Breakthrough Generations, UK, and 785 cases and 791 controls from Athens, Greece; Online Methods) for the most significant SNP from each region reaching P < 10–6 in Stage one and included these results in an Overall meta-analysis of both stages, totaling 15,990 melanoma cases and 26,409 controls. Details of these studies can be found in Supplementary Note. Given that the previous single-largest melanoma GWAS was of 2,804 cases and 7,618 controls11, this meta-analysis represents a fourfold increase in sample size compared to previous efforts to identify the genetic determinants of melanoma risk. Unless otherwise indicated we report the P-values from the Overall meta-analysis combining the two stages (Supplementary Table 3). Forest plots of the individual GWAS study results can be found in Supplementary Figure 1.

All Stage one studies underwent similar quality control (QC) procedures, were imputed using the same reference panel and the results analyzed in the same way, with the exception of the Harvard and MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) studies (see Online Methods). A fixed effects (Pfixed) or random effects (Prandom) meta-analysis was conducted as appropriate depending on between-study heterogeneity. 9,470,333 imputed variants passed QC in at least two studies, of which 3,253 reached Pfixed < 1 × 10–6 and 2,543 reached Pfixed < 5 × 10–8. For reference we provide a list of SNPs that reached a Pfixed, or Prandom if I2 > 31%, value < 1 × 10–7 (Supplementary Table 4). The Stage one meta-analysis genome-wide inflation value (λ) was 1.032, and as λ increases with sample size we also adjusted the λ to a population of 1,000 cases and 1,000 controls30. The resulting λ1000 of 1.002 suggested minimal inflation. Quantile-quantile (QQ) plots for the Stage one meta-analysis and individual GWAS studies can be found in Supplementary Figures 2 and 3. To further confirm that our results were not influenced by inflation, the Stage one meta-analysis was repeated correcting for individual studies’ λ; P-values were essentially unchanged (Online Methods, Supplementary Table 3).

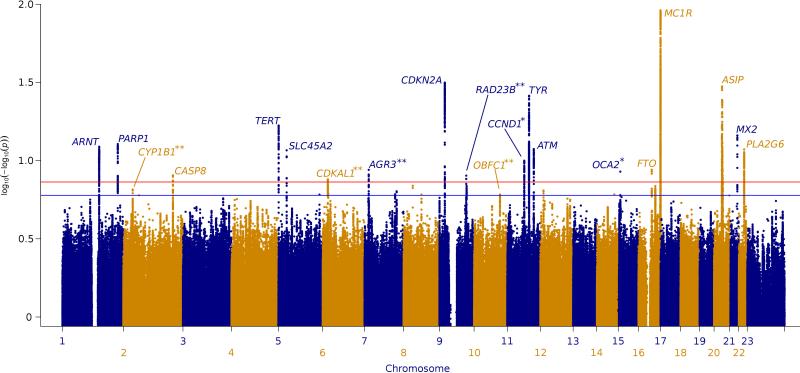

All 13 previously-reported genome-wide significant loci (most first identified in one of the studies included here) reached P < 5 × 10–8 in Stage one (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 4). In addition to confirming the two previously-reported sub-genome-wide significant loci at 11q13.3 (rs498136, 89 kb from CCND1) and 15q13.1 (rs4778138 in OCA2) we found three novel loci reaching genome-wide significance at 6p22.3, 7p21.1, and 9q31.2 (Table 1; Figure 2). SNPs in another 11 regions reached P < 10–6 (Supplementary Table 3); notably, three were close to known telomere-related genes (rs2995264 is in OBFC131 in 10q24.33, rs11779437 is 1.1 Mb from TERF132 in 8q13.3, and rs4731207 is 66 kb from POT1 in 7q31.33, in which loss-of-function variants occur in some melanoma families33,34). Given the importance of telomeres in melanoma we additionally genotyped two SNPs that did not quite reach our P < 10–6 threshold but are close to telomere-related genes35: rs12696304 in 3q26.2 (Pfixed = 1.6 × 10–5) is 1.1 kb from TERC and rs75691080 in 20q13.33 (Pfixed = 1.0 × 10–6) is 19.4 kb from RTEL1. In total 18 SNPs were carried through to Stage two (Online methods).

Figure 1. Manhattan plot of the Stage one meta-analysis of GWAS of CMM from Europe, the USA and Australia.

The Pfixed Stage one value for all SNPs present in at least two studies have been plotted using a log10(–log10) transform to truncate the strong signals at MC1R (P < 10–92) on chromosome 16 and CDKN2A (P < 10–31) on chromosome 9. The total Stage one meta-analysis included 11 CMM GWAS, totaling 12,874 cases and 23,203 controls. P < 5 × 10–8 (genome-wide significance) and P < 1 × 10–6 are indicated by a red and a blue line respectively. 18 loci reached genome-wide significance in Stage one. The 2 newly-confirmed loci 11q13.3 (CCND1) and 15q13.1 (HERC2/OCA2) are indicated by * and the 5 novel loci 2p22.2, 6p22.3, 7p21.1, 9q31.2 and 10q24.33 are highlighted by **. 2p22.2 (RMDN2/CYP1B1) and 10q24.33 (OBFC1) were genome-wide significant only in the Overall meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Genome-wide significant results from a two-stage meta-analysis of GWAS of CMM from Europe, the USA and Australia.

| Stage one meta-analysis | Stage two meta-analysis | Overall meta-analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Region | Gene | Minor Allele:MAF (min INFO) | Beta (P) | Beta (P) | Beta (P) |

| rs6750047 | 2p22.2 | RMDN2 (CYP1B1) | A:0.43 (0.96) | 0.088 (2.9 × 10−7) | 0.113 (6.0 × 10−3) | 0.092 (7.0 × 10−9) |

| rs6914598 | 6p22.3 | CDKAL1 | C:0.32 (0.88) | 0.11 (2.6 × 10−8) | 0.037 (0.63) | 0.10 (3.5 × 10−8)* |

| rs1636744 | 7p21.1 | AGR3 | T:0.40 (0.96) | 0.11 (1.8 × 10−9) | 0.032 (0.38) | 0.091 (7.1 × 10−9) |

| rs10739221 | 9q31.2 | TMEM38B (RAD23B, TAL2) | T:0.24 (0.94) | 0.12 (9.6 × 10−9) | 0.145 (1.7 × 10−3) | 0.12 (7.1 × 10−11) |

| rs2995264 | 10q24.33 | OBFC1 | G:0.088 (0.94) | 0.14 (8.5 × 10−7) | 0.206 (0.088) | 0.16 (2.2 × 10−9) |

| rs498136 | 11q13.3 | CCND1 | A:0.32 (0.97) | 0.12 (1.0 × 10−10) | 0.124 (4.0 × 10−3) | 0.12 (1.5 × 10−12) |

| rs4778138 | 15q13.1 | OCA2 | G:0.16 0.82 | –0.18 (3.1 × 10−9) | –0.156 (1.7 × 10−3) | –0.17 (2.2 × 10−11) |

For each region we report the chromosomal location, nearest gene, and any other promising candidate gene in brackets for the top SNP. We also report the 1000 Genomes European population minor allele frequency (MAF) and minimum imputation quality across all studies (min INFO). The Stage one meta-analysis field reports the effect size estimate (beta) and P-value for the minor allele from the meta-analysis of 11 CMM GWAS, totaling 12,874 cases and 23,203 controls. Following their genotyping in three additional datasets (total 3,116 cases and 3,206 controls) we provide the Stage two meta-analysis results. Finally we provide the Overall meta-analysis of all available data. The results for the top SNP in each region that reached P < 1 × 10−6 in Stage one and so was genotyped in Stage two, per study results and evidence of heterogeneity of effect estimates across studies (I2) can be found in Supplementary Table 3. Where I2 values were below 31% fixed effects meta-analysis was used, otherwise random effects, and all genome-wide significant SNPs had low heterogeneity (I2 < 31%) in both Stage one and Overall. Regions previously confirmed as associated with melanoma (e.g. MC1R) are not shown.

Not genome-wide significant after formal multiple testing correction e.g. P < 3.06 × 10−8 as in Li et al, (2012)93.

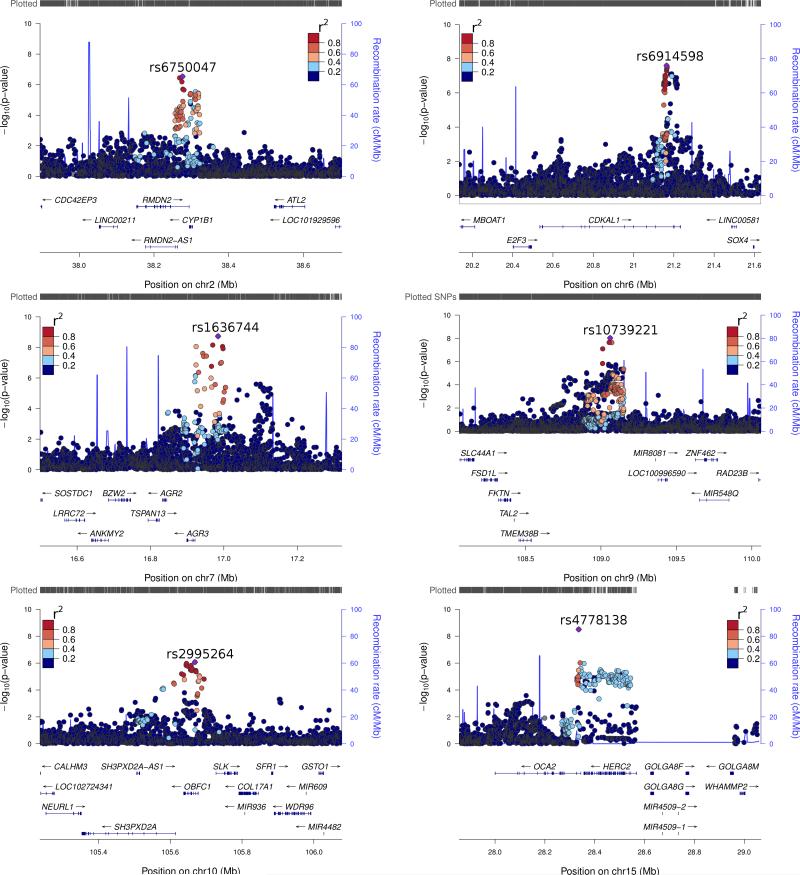

Figure 2. Regional association plots for novel genome-wide significant loci 2p22.2, 6p22.3, 7p21.1, 9q31.2, 10q24.33 and the newly-confirmed region, 15q13.1 (OCA2).

The negative log10 of Pfixed values for SNPs from the Stage one meta-analysis of 12,874 cases and 23,203 controls have been plotted against their genomic position (Mb) using LocusZoom89. The rs ID is listed for the peak SNP in each region (purple diamond). The P-values and effect sizes for listed SNPs can be found in Supplementary Table 3. For the remaining SNPs the color indicates linkage disequilibrium r2 with the peak SNP. Neither rs2995264 in 10q24.33 nor rs6750047 in 2p22.2 are genome-wide significant in Stage one, but reach this in the Overall meta-analysis. The plot for 11q13.3 (CCND1) can be found in Supplementary Figure 4.

Including the Stage two results in the Overall meta-analysis led to two new genome-wide significant regions, 2p22.2 and 10q24.33 (Figure 2; Table 1, Supplementary Table 3). The Stage two data also serve the purpose of independently confirming with genotype data the meta-analysis results from imputed SNPs. Five SNPs, rs4778138 (OCA2/15q13.1), rs498136 (CCND1/11q13.3), and the novel rs10739221 (9q31.2), rs6750047 (2p22.2) and rs2995264 (10q24.33) all reached P < 0.05 in the genotyped Stage two samples. We have estimated the power to reach P < 0.05 in the Stage two samples for all SNPs that reached genome-wide significance in the Stage one meta-analysis (Online Methods, Supplementary Table 5). rs6914598 (6p22.3) was only genotyped in the Athens sample and thus had a power of only 0.35. Of the remaining four SNPs that were genome-wide significant in Stage one, while the 7p21.1 SNP rs1636744 was well powered ( > 90%), the probability that all four of these well-powered SNPs would reach P < 0.05 in the analysis of Stage two data was only (0.916 × 0.736 × 0.787 × 0.955) = 0.51, so it is not surprising that one was not significant. The SNPs in 7p21.1 (rs1636744) and 6p22.3 (rs6914598) did not reach nominal significance in Stage two, but for both SNPs the confidence intervals for the effect estimates overlapped those from the Stage one meta-analysis.

In terms of heritability the 13 loci that were genome-wide significant before this meta-analysis explained 16.9% of the familial relative risk (FRR) for CMM, with MC1R explaining 5.3% alone (Online Methods). Including the seven loci confirmed or reported here (2p22.2, 6p22.3, 7p21.1, 9q31.2, 10q24.33, 11q13.3, 15q13.1), an additional 2.3% of FRR is explained. In total, all 20 loci explain 19.2% of the FRR for CMM; this is a conservative estimate given the assumption of a single SNP per locus.

We tested all new and known CMM risk loci for association with nevus count or pigmentation (Supplementary Table 1). Aside from the known association between OCA2 and pigmentation, none of the newly-identified loci were associated (P > 0.05). Following confirmation of the loci in the Stage two analysis, we performed conditional analysis on the Stage one meta-analysis results to determine whether there were additional association signals within 1 Mb either side of the top SNP at each locus using the Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) software36(Online Methods; Supplementary Table 6). This indicated that while there are additional SNPs associated with CMM at each locus, for all but chromosome 7 and 11 the additional signals were not strongly associated with melanoma (P < 1 × 10–7; for more detail see Supplementary Note and Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). We then conducted a comprehensive bioinformatic assessment of the top SNP from each of the seven new genome-wide significant loci using a range of annotation tools, databases of functional and eQTL results and previously-published GWAS results (see Online Methods, Supplementary Tables 7–9). We applied the same analyses to each locus but, to limit repetition, where nothing was found for a given resource (e.g. NHGRI GWAS catalog) we do not explicitly report this.

2p22.2

While rs6750047 in 2p22.2 was not genome-wide significant in the Stage one meta-analysis it reached genome-wide significance (Pfixed = 7.0 × 10–9, OR = 1.10, I2 = 0.00; Table 1, Supplementary Table 3) in the Stage two and Overall meta-analysis. The association signals for 2p22.2 (Figure 2) span the 3' UTR of RMDN2 (also known as FAM82A1) and the entirety of the CYP1B1 gene, and as such there is a wealth of bioinformatic annotation for SNPs associated with CMM risk. Considering the 26 SNPs with P-values within two orders of magnitude of rs6750047 in 2p22.2 (Supplementary Tables 7–9), HaploReg37 reports a significant enrichment of strong enhancers in epidermal keratinocytes (4 observed, 0.6 expected, P = 0.003). The paired rs162329 and rs162330 (LD r2 =1.0, 98 bp apart; Pfixed = 3.91 ×10–6, I2 = 11.23) lie approximately 10 kb upstream from the CYP1B1 transcription start site in a potential enhancer in keratinocytes and other cell types37-40. These two SNPs are eQTLs for CYP1B1 in three independent liver sample sets41,42. In addition several SNPs, including the peak SNP for 2p22.2, rs6750047, are strong CYP1B1 eQTLs in LCLs in the Multiple Tissue Human Expression Resource43 (MuTHER; P < 5 × 10–5). It is worth noting the overlap between the liver and lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) eQTLs is incomplete; rs162330 and rs162331 are only weak eQTLs in MuTHER data (P ~ 0.01). In terms of functional annotation the most promising SNP near rs6750047 is rs1374191 (Pfixed = 5.4 × 10–5, OR = 1.07, I2 = 0.00); in addition to being a CYP1B1 eQTL in LCLs (MuTHER P = 6.9 × 10–8); this SNP is positioned in a strong enhancer region in multiple cell types including melanocytes and keratinocytes37-40. In summary, SNPs in 2p22.2 associated with melanoma lie in putative melanocyte and keratinocyte enhancers and are also cross-tissue eQTLs for CYP1B1.

CYP1B1 metabolizes endogenous hormones, playing a role in hormone associated cancers including breast and prostate (reviewed in44). CYP1B1 also metabolizes exogenous chemicals, resulting in pro-cancer (e.g. polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) and anti-cancer (e.g. tamoxifen) outcomes44. The former is of interest as CYP1B1 is regulated by ARNT, a gene at the melanoma-associated 1q21 locus12. The CYP1B1 promotor is methylated in melanoma cell lines and tumor samples45. CYP1B1 missense protein variants have been associated with cancers including squamous cell carcinoma and hormone associated cancers44,46. Of these only rs1800440 (p.Asn453Ser) is moderately associated with melanoma (Pfixed = 1.83 × 10–5, OR = 0.90, I2 = 0.00), and it was included in the bioinformatic annotation (Supplementary Tables 7–9). rs1800440 is not in LD with the CMM risk meta-analysis peak SNP rs6750047/2p22.2 (LD r2 = 0.04) and adjusting for rs6750047 only slightly reduces its association with CMM (P = 4.3 × 10–4, Online Methods). Truncating mutations in CYP1B1 are implicated in primary congenital glaucoma47 and since glaucoma cases are used as controls in the contributing Western Australian Melanoma Health Study (WAMHS) melanoma GWAS, we considered the impact of excluding glaucoma cases; the SNP remains genome-wide significantly associated with CMM even after such exclusions (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Table 10). While the association with melanoma in the WAMHS set is stronger without glaucoma cases (beta 0.05 vs. 0.19) both betas are within the range observed for other melanoma datasets and no heterogeneity (I2 = 0.00) is observed with or without the glaucoma samples.

6p22.3

rs6914598 (Pfixed = 3.5 × 10–8, OR = 1.11, I2 = 0.00) lies in 6p22.3, in intron 12 of CDKAL1, a gene that modulates the expression of a range of genes including proinsulin via tRNA methylthiolation48,49. Bioinformatic assessment of the 35 SNPs with P-values within two orders of magnitude of the 6p22.3 peak rs6914598 by HaploReg37 indicates that the most functionally interesting SNP is rs7776158 (Stage one Pfixed = 3.8 × 10–8, I2 = 0, in complete LD with rs6914598, r2 = 1.0), which lies in a predicted melanocyte enhancer that binds IRF438,39. IRF4 binding is of interest given the existence of a functional SNP rs12203592 in the IRF4 gene50, associated with nevus count, skin pigmentation and tanning response51-54.

7p21.1

rs1636744 (Pfixed = 7.1 × 10–9, OR = 1.10, I2 = 0.00; Figure 2) is in an intergenic region of 7p21.1 and lies 63 kb from AGR3. rs1636744 is an eQTL for AGR3 in lung tissue (Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project P = 1.6 × 10–6)55,56. AGR3 is a member of the protein disulphide isomerase family, which generate and modify disulphide bonds during protein folding57. AGR3 expression has been associated with breast cancer risk58 and poor survival in ovarian cancer59. GTEx confirms that AGR3 is expressed in human skin samples. The region containing rs1636744 is not conserved in primates (UCSC genome browser60), and RegulomeDB40 indicates there is little functional activity at this SNP. More promising are rs847377 and rs847404 which, in addition to being both AGR3 eQTLs in lung tissue55 and associated with CMM risk (Stage one Pfixed = 3.89 × 10–8 and 1.72 × 10–7), are in putative weak enhancers in a range of cells including melanocytes and keratinocytes37-40. Adjusting for rs1636744 renders rs847377 and rs847404 non-significant (P > 0.6) indicating that they are tagging a common signal. rs1636744, rs847377 and rs847404 are not eQTLs for AGR3 in sun-exposed skin.

9q31.2

The melanoma-associated variants at 9q31.2, peaking at rs10739221 (Overall Pfixed = 7.1 × 10–11; I2 = 0.00; Figure 2) are intergenic. The nearest genes are TMEM38B, ZNF462 and the nucleotide excision repair gene RAD23B61. While bioinformatic annotation did not reveal any putative functional SNPs, based on the importance of DNA repair in melanoma, RAD23B is of particular interest. rs10739221 is 635 Kb from the leukemia-associated TAL262, and 1.2 Mb from KLF4, which regulates both telomerase activity63 and the melanoma-associated TERT64.

10q24.33

While not genome-wide significant in Stage one, rs2995264 in 10q24.33 is strongly associated with telomere length28,35 and was genotyped in Stage two. rs2995264 was significantly associated with CMM in the Cambridge study (P = 0.046) and strong in the Breakthrough dataset (P = 8.0 × 10–4); in the Overall meta-analysis this SNP reached genome-wide significance (Pfixed = 2.2 × 10–9; I2 = 27.14). The melanoma association signal at 10q24.33 (Figure 2) spans the OBFC1 gene and the promotor of SH3PXD2A. Given the strong telomere length association at this locus the most promising candidate is OBFC1, a component of the telomere maintenance complex31.

HaploReg reports that SNPs within two orders of magnitude of rs2995264 in 10q24.33 are significantly more likely to fall in putative enhancers in keratinocytes than would be expected by chance (P < 0.001). Promising candidate functional SNPs include the conserved rs11594668 and rs11191827 which lie in putative melanocyte and keratinocyte enhancers, and bind transcription factors37-40. The association observed at rs2995264/10q24.33 is independent of a recent report of a melanoma association at 10q25.165. Our peak SNP for 10q24.33, rs2995264, and the 10q25.1 SNPs rs17119434, rs17119461, and rs17119490 reported in Teerlink et al., (2012)65 are in linkage equilibrium (LD r2 <0.01) and in turn these SNPs are not associated with CMM in our meta-analysis (P > 0.2).

11q13.3

The CMM-associated variants at 11q13.3 peak at rs498136 (Overall Pfixed = 1.5 × 10–12, OR = 1.13, I2 = 0.00; Supplementary Figure 6) 5’ to the promotor of CCND1. In the initial report of CCND111 rs11263498 was borderline in its association with melanoma (P = 3.2 × 10–7) and while supported (P = 0.017) by the two replication studies exhibited significant heterogeneity and did not reach genome-wide significance (overall Prandom = 4.6 × 10–4, I2 = 45.00). The previously-reported rs11263498 and the meta-analysis peak of rs498136/11q13.3 are in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 = 0.95).

Bioinformatic assessment of the CCND1 region indicated the peak SNP rs498136/11q13.3 is in a putative enhancer in keratinocytes in both ENCODE and Roadmap data37-40. Considering other SNPs strongly associated with CMM, both the previously-reported11 rs11263498 (Stage one Pfixed = 1.8 × 10–9, OR = 1.12, I2 = 0.00) and rs868089 (Stage one Pfixed = 2.0 × 10–9, OR = 1.12, I2 = 0.00) lie in putative melanocyte enhancers.

Somatic CCND1 amplification in CMM tumors positively correlates with markers of reduced overall survival, including Breslow thickness and ulceration66,67. The CCND1 association with breast cancer has been extensively fine-mapped, revealing three independent association signals68. rs554219 and rs75915166 tag the two strongest functional associations with breast cancer68 but are not themselves associated with CMM risk (Stage one Pfixed > 0.1, I2 = 0.00). While the third signal in breast cancer was not functionally characterized68, its tag SNP rs494406 is modestly associated with CMM (Stage one Pfixed > 0.0002, I2 = 0.00, LD r2=0.47 with rs498136/11q13.3). rs494406 is no longer significant after adjustment by rs498136 (P = 0.53; Supplementary Table 6), suggesting that SNPs that are in LD in this region are associated with risk of both melanoma and breast cancer.

15q13.1

Both OCA2 and nearby HERC2 at the 15q13.1 locus have long been associated with pigmentation traits51. rs12913832 in HERC2, also known as rs11855019, is the major determinant of eye color in Europeans69, making this region a strong candidate for CMM risk. One of the studies contributing to this meta-analysis previously reported a genome-wide significant association between melanoma and rs1129038 and rs12913832 in HERC2 (in strong LD10 reported as r2 = 0.985), but this was not supported (P > 0.05) by any of the three replication GWAS (final P = 2.5 × 10–4)10. Stratification might be an issue for this locus as eye color frequencies vary markedly across European populations. Indeed, in our meta-analysis, which includes all four of these GWAS, both rs1129038 and rs12913832 showed highly heterogeneous effects in the CMM risk meta-analysis (Prandom = 0.037 and 0.075 respectively, I2 > 77.00).

Amos et al., (2011) found that rs4778138 in OCA2, which is only in weak LD with rs12913832 (r2 = 0.12), exhibited a more consistent association across studies, albeit not genome-wide significantly. In our Overall meta-analysis we confirm rs4778138 in 15q13.1 is associated with CMM risk (Pfixed = 2.2 × 10–11, OR = 0.84, I2 = 0.00; Figure 2). Following adjustment of the 15q13.1 signal by rs4778138 the effect size for the eye color SNP rs12913832 is reduced from beta = 0.12 to beta = 0.064. Conversely adjustment for rs12913832 reduces rs4778138's association with CMM (beta reduced from −0.178 to −0.114, corrected P = 1.6 × 10–4). rs12913832 is poorly imputed across studies, reaching INFO > 0.8 in only 6 studies, and we are unable to conclusively exclude a role for rs12913832 at this locus. HaploReg indicates rs4778138 is within a putative melanocyte enhancer in Roadmap epigenetic data37-40. While it is not clear which gene(s) in 15q13.1 is/are influenced by melanoma-associated SNPs, the fact that rs4778138 is associated with eye colors intermediate to blue and brown70 supports a role for OCA2.

Evidence of additional melanoma susceptibility loci

A further nine loci were associated with CMM risk at multiple SNPs with P < 10–6 in Stage one but did not reach P < 5 ×10–8 in the Overall meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 3). Given that genome-wide significance is based on a Bonferroni correction assuming 1,000,000 independent tests, we would expect only one locus to reach P < 10–6 and the probability that as many as nine loci reach this threshold is 1.1 × 10–6 (exact binomial probability), so it is highly likely that several of these are genuine.

Of the 16 regions that reached P < 10–6, three were near genes involved in telomere biology 7q31.33 (rs4731207 near POT1), 8q13.3 (rs11779437 near TERF1), and 10q24.33 (rs2995264 near OBFC1) (Supplementary Table 3). Given the evidence for telomere biology in melanoma20,25-28 and that previous genome-wide significant SNPs are near the telomere maintenance genes TERT, PARP1 and ATM, we included two further biological candidates: rs12696304, 1.1 kb from TERC in 3q26.2, and rs75691080 in 20q13.33 near RTEL1. Of these five SNPs, rs2995264 (10q24.33/OBFC1) attained genome-wide significance in the overall analysis while rs12696304 (3q26.2/TERC) was significant in Stage two (P = 4.0 × 10–3), and reached P = 2.8 × 10–7 in the Overall meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 3). While falling short of genome-wide significance this is nonetheless suggestive of an association at this locus. Neither rs4731207 (66 kb from POT1 in 7q31.33) nor rs75691080 (19.4 kb from RTEL1 in 20q13.33) were significantly associated with melanoma risk in Stage two, but in neither case did the estimated effect differ significantly from Stage one. In addition rs75691080 (RTEL1/20q13.33) is marginally associated with nevus count (P = 0.058; Supplementary Table 1). Of the SNPs near telomere-related genes, rs11779437 in 8q13.3 was the most distant (1.1 Mb from TERF1) and was the only one to show a significantly different effect in Stage two (Overall Prandom = 0.013, OR = 0.93, I2 = 42.06). This is most likely due to the initial signal being a false positive, but may be due to a lack of power.

Conclusion

This two-stage meta-analysis, representing a fourfold increase in sample size compared to the previous largest single melanoma GWAS, has confirmed all thirteen previously reported loci, as well as resolving two likely associations at CCND1 and HERC2/OCA2. The CCND1 association with melanoma only partially overlaps the signal observed for breast cancer68. The HERC2/OCA2 association is with rs4778138/15q13.1, which may be a subtle modifier of eye color70, but we cannot rule out that the association at this locus is influenced by the canonical blue/brown eye color variant rs12913832.

Our Stage one meta-analysis of over 12,000 melanoma cases identified three novel risk regions, with only rs10739221 formally significant (P < 0.05) in Stage two (Table 1). Two further loci (2p22.2 and 10q24.33) reached genome-wide significance with the addition of the Stage two data (Figure 2; Table 1, Supplementary Table 3). In total our Overall meta-analysis identified 20 genome-wide significant loci; 13 previously replicated, two previously-reported but first confirmed here and five that are novel to this report. The new loci identified in this meta-analysis explain an additional 2.3% of the familial relative risk for CMM. Overall, 19.2% of the FRR is explained by all 20 genome-wide significant loci combined.

Except for the association at 9q31.2, the reported loci contain SNPs that are both strongly associated with melanoma and fall within putative regulatory elements in keratinocyte or melanocyte cells, with the nearby nucleotide excision repair gene RAD23B at 9q31.2 a promising candidate. eQTL datasets suggest that melanoma-associated SNPs at 7p21 regulate the expression of AGR3 albeit in lung tissue and not sun-exposed skin. AGR3 expression has been implicated in breast and ovarian cancer outcome. SNPs in 2p22.3 are associated with the expression of CYP1B1. Although this gene is better known for its role in hormone-associated cancers it may influence melanoma risk through metabolism of exogenous compounds, a process regulated by ARNT at the 1q21 melanoma-associated locus.

We have used the power of this large collection of CMM cases and controls to identify five novel loci, none of which are significantly associated with classical CMM risk factors and thus highlight novel disease pathways. Interestingly, we now have genome-wide significant evidence for association between CMM risk and a SNP in the telomere-related gene OBFC1 in 10q24.33, in addition to the established telomere-related associations at the TERT/CLPTM1L, PARP1 and ATM loci. We also have support, albeit not genome-wide significant, for TERC, the most significant predictor of leukocyte telomere length in a recent study35. Of the 20 loci that now reach genome-wide significance for CMM risk, five are in regions known to be related to pigmentation, three in nevus-related regions and four in regions related to telomere maintenance. This gives further evidence that the telomere pathway, with its effect on the growth and senescence of cells, may be important in understanding the development of melanoma.

Online Methods

Stage one array genotyping

The samples were genotyped on a variety of commercial arrays, detailed in the Supplementary Note. All samples were collected with informed consent and with ethical approval (for details see Supplementary Note).

Stage one genome-wide imputation

Imputation was conducted genome-wide, separately on each study, following a shared protocol. SNPs with MAF < 0.03 (MAF < 0.01 in AMFS, Q-MEGA_omni, Q-MEGA_610k, WAMHS, and HEIDELBERG), control Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P < 10–4 or missingness > 0.03 were excluded, as were any individuals with call rates <0.97, identified as first degree relatives and/or European outliers by principal components analysis using EIGENSTRAT71. In addition, in each study where genotyping was conducted on more than one chip, any SNP not present on all chips was removed prior to imputation to avoid bias. IMPUTEv2.272,73 was used for imputation for all studies but Harvard, which used MaCH74,75 and MDACC which used MaCH and minimac76. For GenoMEL, CIDRUK and MDACC samples the 1000 Genomes Feb 2012 data (build 37) was used as the reference panel, while for the AMFS, Q-MEGA_omni, Q-MEGA_610k, WAMHS, MELARISK and HEIDELBERG datasets the 1000 Genomes April 2012 data (build 37) was the reference for imputation77. In both cases any SNP with MAF < 0.001 in European (CEU) samples was dropped from the reference panel. The HARVARD data were imputed using MACH with the NCBI build 35 of phase II HapMap CEU data as the reference panel and only SNPs with imputation quality R2 > 0.95 were included in the final analysis.

Stage one genome-wide association analysis

Imputed genotypes were analyzed as expected genotype counts based on posterior probabilities (gene dosage) using SNPTEST278 assuming an additive model with geographic region as a covariate (SNPTEST v2.5 for chromosome X). MDACC imputed genotypes were analyzed using best guess genotypes from MACH and PLINK was used for logistic association test adjusting by the top two principle components. Only those with an imputation quality score (INFO/MaCH R2) score >0.8 were analyzed. Potential stratification was dealt with in the GenoMEL samples by including geographic region as a covariate (inclusion of principal components as covariates was previously found to make little difference9) and elsewhere by including principal components as covariates71.

Meta-analysis

Heterogeneity of per-SNP effect sizes in studies contributing to the Stage one, Stage two and the Overall meta-analyses was assessed using the I2 metric79. I2 is commonly defined as the proportion of overall variance attributable to between-study variance, with values below 31% suggesting no more than mild heterogeneity. Where I2 was less than 31% a fixed effects model was used, with fixed effects P-values indicated by Pfixed; otherwise random effects were applied (Prandom). The method of Dersimonian and Laird80 was used to estimate the between-studies variance, . An overall random effects estimate was then calculated using the weights where vi is the variance of the estimated effect. for the fixed effects analyses. We report those loci reaching significance at > one marker incorporating information from > one study. Results for rs186133190 in 2p15 were only available from four studies; all other SNPs reported here utilize data from at least eight studies (Supplementary Table 3).

Per-study QQ plots of GWAS P-values are provided (Supplementary Figure 3) and for the Stage one meta-analysis (Supplementary Figure 3A). We also provide the Stage one QQ plot with previously reported regions removed (Supplementary Figure 2B). While there was minimal inflation remaining following PC/region of origin correction, to ensure residual genomic inflation was not biasing our results the meta-analysis was repeated using the genome-wide association meta-analysis software, GWAMA v2.181. Included studies were corrected by inflating SNP variance estimates by their genomic inflation (λ). As expected, given the low level of residual inflation, corrected and uncorrected results were very similar. Genome-wide inflation factor (λ)-corrected P-values are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Stage two genotyping

A single SNP for each of the 16 novel region reaching P < 10–6 in Stage one was subsequently genotyped in 3 additional melanoma case-control sets in Stage two (Supplementary Table 3). Any region that only showed evidence for association with CMM at a single imputed SNP and in only one study was not followed up. Included in the Stage two genotyping were rs75691080 in 20q13.33 which, while not quite reaching P < 10–6, lies 20 kb from RTEL1; and rs12696304 in 3q26.2 which lies 1 kb from TERC. Both these genes are known to be telomere-related and have been associated with leukocyte telomere length35. The 16 novel regions included rs2290419 at 11q13.3 which is 450 kb away from our primary hit in the region of CCND1 (rs498136, Supplementary Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 6) and is in linkage equilibrium with the genome-wide significant hit in this region (r2 = 0.002) so may represent an independent effect.

The first Stage two dataset of 1,797 cases and 1,709 controls from two studies based in Cambridge, UK (see Supplementary Note for details of samples). These were genotyped using TaqMan® assays [Applied Biosystems]. 2 μl PCR reactions were performed in 384 well plates using 10 ng of DNA (dried), using 0.05 μl assay mix and 1 μl Universal Master Mix [Applied Biosystems] according to the manufacturer's instructions. End point reading of the genotypes was performed using an ABI 7900HT Real-time PCR system [Applied Biosystems].

The second was 711 cases and 890 controls from the Breakthrough Generations Study. These were genotyped in the same way as the Cambridge Stage two samples above.

The third was 800 cases and 800 controls from Athens, Greece. Genomic DNA was isolated from 200 μl peripheral blood using the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit [Qiagen]. DNA concentration was quantified in samples prior to genotyping by using Quant-iT dsDNA HS Assay kit [Invitrogen]. The concentration of the DNA was adjusted to 5 ng/μl. Selected SNPs were genotyped using the Sequenom iPLEX assay [Sequenom]. Allele detection in this assay was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization –time-of-flight mass spectrometry82. Since genotyping was performed by Sequenom, specific reaction details are not available. As it is described by Gabriel et al.,82 the assay consists of an initial locus-specific PCR reaction, followed by single base extension using mass-modified dideoxynucleotide terminators of an oligonucleotide primer which anneals immediately upstream of the polymorphic site of interest. Using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, the distinct mass of the extended primer identifies the SNP allele.

Genotyping of 18 SNPs was attempted in Stage two; the rs186133190/2p15. rs6750047/2p22.2, rs498136/11q13.3 and rs4731742/7q32.3 assays failed in one or more Stage two datasets (Supplementary Table 3). After QC (excluding individuals missing >1 genotype call, SNPs missing in > 3% of samples, SNPs with HWE P < 5 × 10–4) there were 1,692 cases and 1,592 controls from Cambridge, 639 cases and 823 controls from Breakthrough Generations and 785 cases and 791 controls from Athens, Greece available for Stage two.

Statistical power for Stage two

We have estimated the power to reach P < 0.05 in the Stage two samples for all SNPs that reached genome-wide significance in the Stage one meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 3). We converted ORs to genotype relative risks (as the SNPs are relatively frequent this is a reasonable assumption) and estimated power by simulating cases and controls (10,000 iterations) and conducting a Cochran-Armitage trend test (see Supplementary Table 5).

Conditional Analysis

Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA)36 was used to perform conditional/joint GWAS analysis of newly identified or confirmed loci. GCTA allows conditional analysis of summary meta-analysis if provided with a sufficiently large reference population (2–5,000 samples) used in the meta-analysis to estimate LD. We used the QMEGA-610k set as a reference population to determine LD. QMEGA-610k imputation data for well imputed SNPs (INFO > 0.8) was converted to best guess genotypes using the GTOOL software (see URLs).

Following best-guess conversion (genotype probability threshold 0.5), SNPs with a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P < 1 × 10−6, a MAF < 0.01 and > 3% missingness were removed. As per Yang et al., (2011)36 we further cleaned the QMEGA-610K dataset to include only completely unrelated individuals (Identity by descent score ≤ 0.025 versus the standard 0.2 used in the meta-analysis), leaving a total of 4,437 people and 7.24 million autosomal SNPs in the reference panel.

Within each new locus, Stage one fixed effects summary meta-analysis data for SNPs within 1 Mb either side of the top SNP were adjusted for the top SNP using the --cojo-cond option. As per Yang et al., (2011) we used the genomic control corrected GWAS-meta-analysis results. Where there remained an additional SNP with P < 5 × 10–8 following adjustment for the top SNP we performed an additional round including both SNPs. If the remaining SNPs had P-values greater than 5 × 10–8 no further analysis was performed. The results of this analysis are reported in Supplementary Table 6.

Proportion of Familial Relative Risk

We have used the formula for calculating the proportion of familial relative risk (FRR) as outlined by the Cancer Oncological Gene-environment Study (see URLs). Given that CMM incidence is low, and the odds ratios reported small, we have assumed the odds ratios derived from the Stage one meta-analysis are equivalent to relative risks. With this assumption we have estimated the proportion of the FRR explained by each SNP (FRRsnp) as FRRsnp = (pr2 + q)/ (pr + q)2

Where risk allele and alternative allele frequency are p and q respectively, and r is the odds ratio for the risk allele

Assuming a FRRmelanoma for CMM of 2.1983 and using the combined effect of all SNPs (assuming a multiplicative effect and a single SNP per loci), we computed the proportion of FRR is explained by a set of SNPs as loge(product of FRRsnp)/ loge(FRRmelanoma).

Association with nevus count or pigmentation

Pigmentation and nevus phenotype data were available for 980 melanoma cases and 499 control individuals from the Leeds case-control study84,85. Additional individuals from the Leeds melanoma cohort study86 had pigmentation data available, giving a total of 1,458 subjects with melanoma and 499 control subjects. For the most significant SNP in each region reaching P < 1 × 10–6 in the initial meta-analysis, log-transformed age- and sex-adjusted total nevus count was regressed on the number of risk alleles, adjusting for case-control status. A sun-sensitivity score was calculated for all subjects based on a factor analysis of six pigmentation variables (hair color, eye color, self-reported freckling as a child, propensity to burn, ability to tan and skin color on the inside upper arm)19. This score was similarly regressed on number of risk alleles and adjusted for case-control status. Full results can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Bioinformatic annotation

As the SNP most associated with the phenotype is quite likely not the underlying functional variant87, we performed a comprehensive bioinformatic assessment of SNPs with Pfixed (if I2 < 31%) or Prandom (if I2 ≥ 31%) values within a factor of 100 of the P value for the peak SNP. To ensure we were not missing potentially interesting functional candidates, HaploReg was used to identify additional SNPs with r2 >0.8 and no more than 200 kb away from those SNPs with P values within a factor of 100 of the peak SNP using 1000 Genomes Project pilot data. GCTA was used to confirm that SNPs carried forward for bioinformatic assessment derived from a common signal. Following adjustment for the locus’ top SNP, the SNPs selected for bioinformatic annotation at 6p22.3, 7p21.1, 10q24, 11q13.3 and 15q13.1 had CMM association P > 0.01. At 9q31.2 a single SNP rs1484384 retained a modest melanoma association (P = 0.008) following adjustment for rs10739221; the rest were P > 0.01. At 2p22.2 those SNPs with P-values within 2 orders of magnitude of the peak SNP rs6750047 included rs1800440, a non-synonymous SNP with limited LD with rs6750047 (LD r2 = 0.04). Following adjustment for rs6750047, the significance of rs1800440 was essentially unchanged (P = 4.3 × 10–4) and a second SNP rs163092 remained weakly associated with melanoma (P = 0.008); all other SNPs had P > 0.01. Adjustment for both rs6750047 and rs1800440 removed the association between rs163092 and CMM (P > 0.01).

HaploReg37 and RegulomeDB40 were crosschecked to explore data reflecting transcription factor binding, open chromatin and the presence of putative enhancers. These tools summarize and collate data from the ENCODE39 and Roadmap Epigenomics38 public databases and from a range. ENCODE and Roadmap have assayed a large number of different cell types including keratinocyte and melanocyte primary cells, and, for a limited number of assays, melanoma cell lines; predicted functional activity in these cell types was given priority over cell types less likely to be involved in CMM risk. The summary results reported by HaploReg and RegulomeDB assign regions a putative function based on the combined results of multiple functional experiments and their position relative to known genes38,39. For example, ENCODE assigns the label of predicted enhancer to areas of open chromatin that overlaps a H3K4me1 signal, and binds transcription factors39. The Roadmap Epigenome uses as similar ranking system to ENCODE, and is summarized in the documentation for HaploReg37. For example, a weak enhancer will have only a weak H3K36me3 signal, while an active enhancer will have strong H3K36me3, H3K4me1 and H3K27ac signals. These labels are further divided into weak and strong depending on the quality of evidence. While these labels are predicted or putative, ENCODE reports that >50% of predicted enhancers are confirmed by follow up assays39, and these serve as a useful guide for interrogating CMM associated SNPs. Results from these tools were followed up in more detail using the UCSC genome browser60 to explore the ENCODE 39 and the Roadmap epigenomics project38 data.

In addition, HaploReg uses genome-wide SNPs to estimate the background frequency of SNPs occurring in putative enhancer regions; this was used to test for enrichment in CMM-associated SNPs with an uncorrected binomial test threshold of P = 0.0537.

The eQTL browser, the Genotype-Tissue Expression dataset (GTEx)55, and the Multiple Tissue Human Expression Resource (MuTHER43,88) were further interrogated to attempt to resolve potential genes influenced by disease associated SNPs. For these databases we report only cis results; details of cell types and definition of cis boundaries can be found in Supplementary Tables 7–9. The peak SNP for each locus, as well as other functionally interesting SNPs identified by HaploReg and RegulomeDB, were used to search listed eQTL databases. As the SNP coverage can differ for each database, where SNPs of interest were not present in the eQTL datasets we searched using high LD (>0.95) proxies. While priority was given to cell types more likely to be involved in CMM biology (e.g. sun-exposed skin from GTEx or skin from MuTHER) we reported eQTLs from other tissue types to highlight potential functional impact for identified SNPs.

Regional plots of –log10P-values were generated using LocusZoom89. Where pairwise linkage disequilibrium measures are given, these were estimated from the 379 European ancestry 1000 Genomes Phase 1 April 2012 samples using PLINK90 or the --hap-r2 command in VCFtools91 unless otherwise indicated.

To test for any overlap with published GWAS association, results reported in the NHGRI catalog for reported loci were extracted on 24/07/2014 and cross checked against the Stage one meta-analysis results.

Additional methods

Manhattan plots were generated in R based on scripts written by Stephen Turner (see URLs). Forest plots were generated using the R rmeta package92.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Please see the Supplementary Note for acknowledgements.

Footnotes

URLs

GenoMEL, http://www.genomel.org/; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium http://www.wtccc.org.uk/; RegulomeDB, http://RegulomeDB.org/; HaploReg http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/; GTEx http://www.gtexportal.org, MuTHER http://www.muther.ac.uk/, eQTL data accessed via GeneVAR http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/genevar/, eQTL Browser http://eqtl.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/gbrowse/eqtl/; NHGRI GWAS catalog: http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies/; Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) http://www.complextraitgenomics.com/software/gcta/; GTOOL http://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~cfreeman/software/gwas/gtool.html; Cancer Oncological Gene-environment Study http://www.nature.com/icogs/primer/common-variation-and-heritability-estimates-for-breast-ovarian-and-prostate-cancers/#70; VCFtools http://vcftools.sourceforge.net/; R scripts for Manhattan and QQ plots http://gettinggeneticsdone.blogspot.com.au/2011/04/annotated-manhattan-plots-and-qq-plots.html, rmeta R package for forest plots, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rmeta/rmeta.pdf.

Author Contributions

MMI led, designed and carried out the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. MHL led, designed and carried out the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. MH was involved in the Leeds genotyping design. JCT carried out statistical analyses. JR-M carried out genotyping and contributed to the interpretation of genotyping data. NvdS carried out genotyping and contributed to the interpretation of genotyping data. JANB led the GenoMEL consortium and contributed to study design. NAG was deputy lead of the consortium and contributed to study design. SMacG designed and led the overall study. NKH designed and led the overall study. DTB designed and led the overall study. JHB designed and led the overall study. JH supervised and carried out statistical analysis of the Harvard GWAS data. FS carried out statistical analysis of the Harvard GWAS data. AAQ carried out statistical analysis of the Harvard GWAS data. CIA led and carried out statistical analysis of the M.D. Anderson GWAS data. WVC contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the M.D. Anderson GWAS data. JEL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the M.D. Anderson GWAS data. SF contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the M.D. Anderson GWAS data. FD led, designed and contributed to the sample collection, analysis and interpretation of the French MELARISK GWAS data and advised on the overall statistical analysis. MB contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the French MELARISK GWAS data. MFA led, designed and contributed to the sample collection of the French MELARISK GWAS data. GML led and contributed to the genotyping and interpretation of the French MELARISK GWAS data. RK led, and contributed to the sample collection and analysis for the Heidelberg dataset. DS led and contributed to the sample collection and analysis for the Heidelberg dataset. HJS contributed to the sample collection and analysis for the Heidelberg dataset. SVW led and contributed to the sample collection for the WAMHS study. EKM provided coordination and oversight for the WAMHS study. DCW led designed, and contributed to the sample collection for the SDH dataset. JEG led and designed the Glaucoma study. KPB contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the Glaucoma dataset. GLR-S led and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the IBD dataset. LS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the IBD dataset. GJM led and contributed to the sample collection, analysis and interpretation of the AMFS study. AEC contributed to the sample collection, analysis and interpretation of the AMFS study. DRN contributed to the sample collection and analysis of Q-MEGA, Endometriosis and QTWIN datasets. NGM led the sample collection and analysis of Q-MEGA and QTWIN datasets. GM led the sample collection and analysis of Endometriosis datasets, and contributed to the sample collection and analysis of Q-MEGA, Endometriosis and QTWIN datasets. DLD contributed to the sample collection and analysis of Q-MEGA, Endometriosis and QTWIN datasets. KMB contributed to the sample collection and analysis of Q-MEGA and QTWIN datasets. AJStratigos interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Athens Stage two dataset. KPK interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Athens Stage two dataset. AMG advised on statistical analysis. PAK advised on statistical analysis. EMG advised on statistical analysis. DEE contributed to the design of the GenoMEL GWAS. AJS interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Breakthrough Generations Study. NO interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Breakthrough Generations Study. LAA contributed to sample collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. PAA contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. EA contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. GBS contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. TD contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. EF contributed to sample collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. PGh contributed to sample collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. JH contributed to sample collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. PHe contributed to sample collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. MHo contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. VH contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. CIn contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. MTL contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. JLang contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. RMM contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. AM contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. JLub. contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. SN contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. HO contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. SP contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. JAP-B contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. RvD contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of GenoMEL datasets. KAP interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Cambridge Stage two dataset. AMD interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Cambridge Stage two dataset. PDPP interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Cambridge Stage two dataset. DFE interpreted and contributed genotype data for the Cambridge Stage two dataset. PGal. contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of the SU.VI.Max French control dataset. All authors provided critical review of the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Holly EA, Aston DA, Cress RD, Ahn DK, Kristiansen JJ. Cutaneous melanoma in women. II. Phenotypic characteristics and other host-related factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:934–42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holly EA, Aston DA, Cress RD, Ahn DK, Kristiansen JJ. Cutaneous melanoma in women. I. Exposure to sunlight, ability to tan, and other risk factors related to ultraviolet light. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:923–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naldi L, et al. Cutaneous malignant melanoma in women. Phenotypic characteristics, sun exposure, and hormonal factors: a case-control study from Italy. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Titus-Ernstoff L, et al. Pigmentary characteristics and moles in relation to melanoma risk. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:144–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bataille V, et al. Risk of cutaneous melanoma in relation to the numbers, types and sites of naevi: a case-control study. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1605–11. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang YM, et al. A pooled analysis of melanocytic nevus phenotype and the risk of cutaneous melanoma at different latitudes. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:420–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon-Albright LA, Bishop DT, Goldgar C, Skolnick MH. Genetic predisposition to cancer. Important Adv Oncol. 1991:39–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown KM, et al. Common sequence variants on 20q11.22 confer melanoma susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:838–40. doi: 10.1038/ng.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop DT, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three loci associated with melanoma risk. Nat Genet. 2009;41:920–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amos CI, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci predisposing to cutaneous melanoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:5012–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett JH, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new melanoma susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1108–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macgregor S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new melanoma susceptibility locus at 1q21.3. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1114–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iles MM, et al. A variant in FTO shows association with melanoma risk not due to BMI. Nat Genet. 2013;45:428–32. 432, e1. doi: 10.1038/ng.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudbjartsson DF, et al. ASIP and TYR pigmentation variants associate with cutaneous melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2008;40:886–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonopoulou K, et al. Updated field synopsis and systematic meta-analyses of genetic association studies in cutaneous melanoma: the MelGene database. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1074–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pena-Chilet M, et al. Genetic variants in PARP1 (rs3219090) and IRF4 (rs12203592) genes associated with melanoma susceptibility in a Spanish population. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falchi M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at 9p21 and 22q13 associated with development of cutaneous nevi. Nat Genet. 2009;41:915–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafnar T, et al. Sequence variants at the TERT-CLPTM1L locus associate with many cancer types. Nat Genet. 2009;41:221–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pooley KA, et al. No association between TERT-CLPTM1L single nucleotide polymorphism rs401681 and mean telomere length or cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1862–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nan H, Qureshi AA, Prescott J, De Vivo I, Han J. Genetic variants in telomere-maintaining genes and skin cancer risk. Hum Genet. 2011;129:247–53. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Law MH, et al. Meta-analysis combining new and existing data sets confirms that the TERT-CLPTM1L locus influences melanoma risk. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:485–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mocellin S, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase locus polymorphisms and cancer risk: a field synopsis and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:840–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez M, et al. PARP1 Is a TRF2-associated poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase and protects eroded telomeres. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1686–96. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derheimer FA, Kastan MB. Multiple roles of ATM in monitoring and maintaining DNA integrity. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3675–81. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bataille V, et al. Nevus size and number are associated with telomere length and represent potential markers of a decreased senescence in vivo. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1499–502. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han J, et al. A prospective study of telomere length and the risk of skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:415–21. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke LS, et al. Telomere length and the risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in melanoma-prone families with and without CDKN2A mutations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iles MM, et al. The effect on melanoma risk of genes previously associated with telomere length. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett JH, et al. Fine mapping of genetic susceptibility loci for melanoma reveals a mixture of single variant and multiple variant regions. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1351–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Bakker PI, et al. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R122–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyake Y, et al. RPA-like mammalian Ctc1-Stn1-Ten1 complex binds to single-stranded DNA and protects telomeres independently of the Pot1 pathway. Mol Cell. 2009;36:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Steensel B, de Lange T. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature. 1997;385:740–3. doi: 10.1038/385740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robles-Espinoza CD, et al. POT1 loss-of-function variants predispose to familial melanoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:478–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi J, et al. Rare missense variants in POT1 predispose to familial cutaneous malignant melanoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:482–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Codd V, et al. Identification of seven loci affecting mean telomere length and their association with disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:422–7. 427, e1–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:369–375. doi: 10.1038/ng.2213. [PubMed: 22426310] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D930–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein BE, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyle AP, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–7. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schadt EE, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Innocenti F, et al. Identification, replication, and functional fine-mapping of expression quantitative trait loci in primary human liver tissue. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grundberg E, et al. Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1084–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gajjar K, Martin-Hirsch PL, Martin FL. CYP1B1 and hormone-induced cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012;324:13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muthusamy V, et al. Epigenetic silencing of novel tumor suppressors in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11187–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen M, et al. Quantitative assessment of the influence of CYP1B1 polymorphisms and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma risk. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:3891–7. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoilov I, Akarsu AN, Sarfarazi M. Identification of three different truncating mutations in cytochrome P4501B1 (CYP1B1) as the principal cause of primary congenital glaucoma (Buphthalmos) in families linked to the GLC3A locus on chromosome 2p21. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:641–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arragain S, et al. Identification of eukaryotic and prokaryotic methylthiotransferase for biosynthesis of 2-methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine in tRNA. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28425–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brambillasca S, et al. CDK5 regulatory subunit-associated protein 1-like 1 (CDKAL1) is a tail-anchored protein in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of insulinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41808–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.376558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Praetorius C, et al. A polymorphism in IRF4 affects human pigmentation through a tyrosinase-dependent MITF/TFAP2A pathway. Cell. 2013;155:1022–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sulem P, et al. Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1443–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han J, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel alleles associated with hair color and skin pigmentation. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duffy DL, et al. IRF4 variants have age-specific effects on nevus count and predispose to melanoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang M, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify several new loci associated with pigmentation traits and skin cancer risk in European Americans. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2948–59. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Consortium GT. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Consortium GT. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Persson S, et al. Diversity of the protein disulfide isomerase family: identification of breast tumor induced Hag2 and Hag3 as novel members of the protein family. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;36:734–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fletcher GC, et al. hAG-2 and hAG-3, human homologues of genes involved in differentiation, are associated with oestrogen receptor-positive breast tumours and interact with metastasis gene C4.4a and dystroglycan. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:579–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.King ER, et al. The anterior gradient homolog 3 (AGR3) gene is associated with differentiation and survival in ovarian cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:904–12. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318212ae22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Research. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masutani C, et al. Purification and cloning of a nucleotide excision repair complex involving the xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein and a human homologue of yeast RAD23. EMBO J. 1994;13:1831–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xia Y, et al. TAL2, a helix-loop-helix gene activated by the (7;9)(q34;q32) translocation in human T-cell leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11416–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong CW, et al. Kruppel-like transcription factor 4 contributes to maintenance of telomerase activity in stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1510–7. doi: 10.1002/stem.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffmeyer K, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates telomerase in stem cells and cancer cells. Science. 2012;336:1549–54. doi: 10.1126/science.1218370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teerlink C, et al. A unique genome-wide association analysis in extended Utah high-risk pedigrees identifies a novel melanoma risk variant on chromosome arm 10q. Hum Genet. 2012;131:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1048-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vizkeleti L, et al. The role of CCND1 alterations during the progression of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:2189–99. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Young RJ, et al. Loss of CDKN2A expression is a frequent event in primary invasive melanoma and correlates with sensitivity to the CDK4/6 inhibitor PD0332991 in melanoma cell lines. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:590–600. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.French JD, et al. Functional variants at the 11q13 risk locus for breast cancer regulate cyclin D1 expression through long-range enhancers. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:489–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duffy DL, et al. A three-single-nucleotide polymorphism haplotype in intron 1 of OCA2 explains most human eye-color variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:241–52. doi: 10.1086/510885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruiz Y, et al. Further development of forensic eye color predictive tests. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2013;7:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y, Willer C, Sanna S, Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Genomes Project, C. et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–13. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Magi R, Morris AP. GWAMA: software for genome-wide association meta-analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D. SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0212s60. Chapter 2, Unit 2 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cho E, Rosner BA, Feskanich D, Colditz GA. Risk factors and individual probabilities of melanoma for whites. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2669–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Newton-Bishop JA, et al. Melanocytic nevi, nevus genes, and melanoma risk in a large case-control study in the United Kingdom. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2043–54. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Newton-Bishop JA, et al. Relationship between sun exposure and melanoma risk for tumours in different body sites in a large case-control study in a temperate climate. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:732–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Newton-Bishop JA, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels are associated with breslow thickness at presentation and survival from melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5439–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Edwards SL, Beesley J, French JD, Dunning AM. Beyond GWASs: illuminating the dark road from association to function. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:779–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nica AC, et al. The architecture of gene regulatory variation across multiple human tissues: the MuTHER study. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pruim RJ, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Danecek P, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lumley T. rmeta: Meta-analysis. R package version 2.16 edn. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li MX, Yeung JM, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Hum Genet. 2012;131:747–56. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.