Abstract:

Brain injury during cardiac surgery can cause a potentially disabling syndrome consisting mainly of cognitive dysfunction but can manifest itself as symptoms and signs indistinguishable from frank stroke. The cause of the damage is mainly the result of emboli consisting of solid material such as clots or atherosclerotic plaque, fat, and/or gas. These emboli enter the cerebral circulation from the cardiopulmonary bypass machine, break off the aorta during manipulation, and enter the circulation from cardiac chambers. This damage can be prevented or at least minimized by avoiding aortic manipulation, filtering aortic inflow from the pump, preventing air from entering the pump plus careful deairing of the heart. Shed blood from the cardiotomy suction should be processed by a cell saver whenever possible. By doing these maneuvers, inflammation of the brain can be avoided. Long-term neurocognitive damage has been largely prevented in large series of patients having high-risk surgery, which makes these preventive measures worthwhile.

Keywords: brain damage, cardiopulmonary bypass, emboli, inflammation

Small injuries to the brain that occur during cardiac surgery may produce symptomatic, functional losses that would not be detectable or important in other organs. Regional hypoperfusion, edema, microemboli, circulating cytotoxins, or subtle changes in blood glucose, insulin, or calcium may result in changes in cognitive function, ranging from subtle to profound. A small 2-mm infarct may cause a disruption of behavioral patterns, physiologic and physical function changes can pass unnoticed, be accepted and dismissed, or profoundly compromise the patient’s quality of life. The same sized lesion in the internal capsule may result in a catastrophic stroke making the location of the lesion an important factor in outcome. Thus, the brain, the most sensitive organ exposed to damage by cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and the organ that, with the heart, is most important to protect (1).

ASSESSMENT

Routine assessment of neurologic injury, which occurs in the setting of cardiac surgery, is not done for most patients because of the priority of the cardiac lesion and because of costs in time and money. General neurologic examinations by members of the surgical team or individuals lacking specialized training are not adequate to rule out subtle neurologic injuries, and this is the principal reason that the incidence of stroke, neurologic or neuropsychological injury, varies widely in the surgical literature (2).

For studies designed to assess or reduce neurologic injury in the setting of cardiac surgery, nonroutine preoperative and postoperative tests are required. These special tests include a complete neurologic examination by a neurologist or a well-trained surrogate. To improve accuracy, a single neurologist should ideally conduct all serial examinations. A standardized protocol of examination should be followed with uniform reporting of results. The basic, structured examination includes a mental state examination; cranial nerve, motor, sensory, and cerebellar examinations; and examination of gait, station, deep tendon, and primitive reflexes.

The most obvious neurologic abnormalities are paresis, loss of vital brain functions such as speech, vision, comprehension, or coma. These are commonly lumped under the general heading of stroke. Disorders of awareness or consciousness can include coma, delirium, and confusion, but transitory episodes of delirium and confusion are often dismissed as a result of anesthesia or medications. More subtle losses are determined by comparison of preoperative and postoperative performances using a standard battery of neuropsychologic tests prepared by a group of neuropsychologists. A neuropsychological examination is basically an extension of the neurologic examination with a much greater emphasis on higher cortical function. Dysfunction is objectively defined as a deviation from the expected relative to a large population. For example, although performing at a 95 IQ level is in the normal range, it is low for a physician and a search for a neurologic impairment would be triggered by such a poor performance. A 20% decline in two or more of these tests, compared with the patient’s own baseline, suggests a neuropsychological deficit that should be followed until resolved or not resolved. In studies involving long-term follow-up, the inclusion of a control group of unoperated patients with the same disease and of similar demographics helps define the causes of neuropsychological decline, which occurs later than 3–6 months after surgery (3).

Computed axial tomograms or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are essential for the definitive diagnosis of stroke, delirium, or coma. Preoperative imaging is usually not necessary when new techniques such as diffusion-weighted MRI, MRI spectroscopy, or MRI angiography are used to assess possible new lesions after operation (4). Histological studies performed on patients who did not survive cardiac surgery have demonstrated millions of small lipid microemboli (SCADs), which may result in massive cell loss and increased volume of ventricles (5).

Biochemical markers of neurologic injury after cardiac surgery are relatively nonspecific and inconclusive. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is an intracellular enzyme found in neurons, normal neuroendocrine cells, platelets, and erythrocytes (6). S-100 is an acidic calcium-binding protein found in the brain (7). The beta dimer resides in glial and Schwann cells. Both S-100 and NSE increase in spinal fluid with neuronal death and may correlate with stroke or spinal cord injury after CPB (8). However, plasma levels are contaminated by aspiration of wound blood into the pump and hemolysis and are often elevated after prolonged CPB in patients without otherwise detectable neurologic injury (9,10). Newer bloodborne biochemical markers are being identified but, as of yet, have not been shown to be diagnostic for subtle neurologic injury (11).

POPULATIONS AT RISK

Advancing age increases the risk of stroke or cognitive impairment in the general population, and surgery, regardless of type, increases the risk still higher (Table 1). In 1999 Hogue and colleagues (12) reported the risk of stroke during coronary artery bypass graft surgery to be related to age and other factors. A European study compared 321 elderly patients without surgery with 1218 patients who had noncardiac surgery and found a 26% incidence of cognitive dysfunction after surgery, 1 week after operation, and a 10% incidence at 3 months (13). Between 1974 and 1990 the number of patients undergoing cardiac surgery over age 60 years and over age 70 years increased twofold and sevenfold, respectively (14). In this day and age patients 75 years of age and older commonly receive cardiac surgery with good results if maximal medical therapy fails to relieve symptoms (15). Genetic factors also influence the incidence of cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery (16).

Table 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for Type I and Type II cerebral outcomes associated with selected risk factors.

| Model for Type 1 Cerebral Outcome |

||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds Ratio | Model for Type II Cerebral Outcome |

| Significant factors (p < .05) | ||

| Proximal aortic atherosclerosis | 4.52 | |

| History of neurologic disease | 3.19 | |

| Use of intra-aortic balloon pump | 2.60 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.59 | |

| History of hypertension | 2.31 | |

| History of pulmonary disease | 2.09 | 2.37 |

| History of unstable angina | 1.83 | |

| Age (per additional decade) | 1.75 | 2.20 |

| Systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg at admission | 3.47 | |

| History of excessive alcohol consumption | 2.64 | |

| History of coronary artery bypass grafting | 2.18 | |

| Dysrhythmia on day of surgery | 1.97 | |

| Antihypertensive therapy | 1.78 | |

| Other factors (p not significant) | ||

| Perioperative hypotension | 1.92 | 1.88 |

| Ventricular venting | 1.83 | |

| Congestive heart failure on day of surgery | 2.46 | |

| History of peripheral vascular disease | 1.64 |

Adapted from Roach GW, Kanchugar M, Mangano CM, et al. Adverse cerebral outcomes after coronary bypass surgery. Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Groups and the Ischemia Research and Education Foundation Investigators. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1857–63, with permission.

As the age of cardiac surgical patients increases, the number with multiple risk factors for neurologic injury also increases. Risk factors for adverse cerebral outcomes are listed in Table 1 (17). These factors are divided into stroke with a permanent fixed neurological deficit (Type 1) and coma or delirium (Type 2). Diabetes occurs in approximately 25% of cardiac surgical patients (18). Fifteen percent have carotid stenosis of 50% or greater, and up to 13% have had a transient ischemic attack or prior stroke. The total number of MRI atherosclerotic lesions in the brachiocephalic vessels adds to the risk of stroke or cognitive dysfunction (19) as does the severity of atherosclerosis in the ascending aorta as detected by epiaortic ultrasound scanning (20). Palpable ascending aortic atherosclerotic plaques markedly increase the risk of right carotid arterial emboli as detected by Doppler ultrasound (21).

MECHANISMS OF INJURY

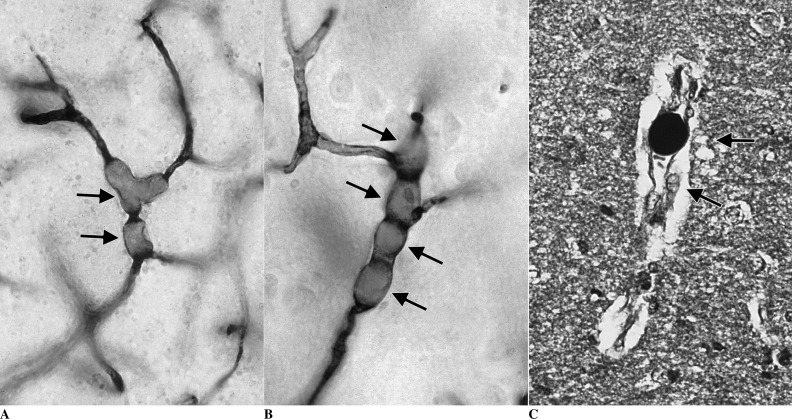

The three major causes of neurologic dysfunction and injury during cardiac surgery are microemboli, hypoperfusion, and a generalized inflammatory reaction, which can occur in the same patient at the same time for different reasons. Many intraoperative strokes are the result of the embolization of atherosclerotic material from the aorta and brachiocephalic vessels. This occurs as a result of manipulation of the heart and major thoracic vasculature as well as dislodgement of atheromata from shearing forces directed at the walls of vessels from inflow cardiopulmonary bypass cannulae (22). Microemboli are distributed in proportion to blood flow; thus, reduced cerebral blood flow reduces microembolic injury but increases the risk of hypoperfusion (23). During CPB, both alpha-stat acid-base management and phenylephedrine reduce cerebral injury in adults, probably by causing cerebral vessel vasoconstriction and reducing the number of microemboli (24,25). Air, atherosclerotic debris, and fat are the major types of microemboli causing brain injury in clinical practice, and all cause neuronal necrosis by blocking cerebral vessels (5). Massive air embolism causes a large ischemic injury, but gaseous cerebral microemboli may directly damage endothelium in addition to blocking blood flow (26). The identification of unique SCADs in the brain associated with fat emboli (Figure 1) raises the possibility that these emboli not only block small vessels, but also release cytotoxic free radicals, which may significantly increase the damage to lipid-rich neurons (27).

Figure 1.

(A–B) Small lipid microemboli (SCADs) in arterioles (dark arrows), vasospasm (white arrow). (C) SCAD stained black with osmium indicating fat. Arrows indicate tissue edema and vacuoles from injury. Osmium-stained, paraffin-embedded 5-mm thick section.

Anemia and elevated cerebral temperature increase cerebral blood flow but may cause inadequate oxygen delivery to the brain (28); however, these conditions are easily avoided during clinical cardiac surgery. Although some investigators speculate that normothermic and/or hyperthermic CPB cause cerebral hypoperfusion, experimental studies indicate that cerebral blood flow increases with temperature (29). Brain injuries associated with this practice are more likely the result of increased cerebral microemboli, which produce larger lesions at higher cerebral temperatures (5). Reduced brain temperature is protective against neural cell injury and remains an important neuroprotective strategy (30).

Surgery, like accidental trauma, triggers an acute inflammatory response, which can result in neurologic injury, but the continuous exposure of heparinized blood to nonendothelial cell surfaces followed by reinfusion of wound blood and recirculation within the body greatly magnifies this response in operations in which CPB is used (31). Although far from fully described and understood, this primary “blood injury” produces a unique response, which is different in detail from that caused by other threats to homeostasis.

The principal blood elements involved in this acute defense reaction are contact and complement plasma protein systems, neutrophils, monocytes, endothelial cells, and to a lesser extent platelets. When activated during CPB, the principal blood elements release vasoactive and cytotoxic substances; produce cell signaling inflammatory and inhibitory cytokines; express complementary cellular receptors that interact with specific cell signaling substances and other cells; and generate a host of vasoactive and cytotoxic substances that circulate (32). Normally these reactive blood elements mediate and regulate the defense reaction (33,34), but during CPB, an orderly, targeted response is overwhelmed by the massive activation and circulation of these reactive blood elements. This massive attack damages the endothelium, increases the size of ischemic lesions, and causes organ dysfunction.

STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING INJURY

Important methods for reducing emboli deserve emphasis. Principles include adequate anticoagulation; washing blood aspirated from the surgical wound; filtering arterial inflow and venous outflow; strict control of all air entry sites within the perfusion circuit; removal of residual air from the heart and great vessels; and avoidance of anemia and atherosclerotic emboli (35–37).

Many intraoperative strategies are available to reduce cerebral atherosclerotic embolization. These include routine epiaortic echocardiography of the ascending aorta to detect both anterior and posterior atherosclerotic plaques and to find sites free of atherosclerosis for placing the aortic cannula, clamps, and bypass grafts (38). In patients with moderate or severe ascending aortic atherosclerosis, a single application of the aortic clamp as opposed to partial or multiple applications is strongly recommended and has been shown to reduce postoperative neurocognitive deficits in a large clinical series (39).

No aortic clamp may be safe or even possible in some patients with severe atherosclerosis or porcelain aorta. If intracardiac surgery is required in these patients, deep hypothermia may be used with or without graft replacement of the ascending aorta. If only revascularization is needed, pedicled single or sequential arterial grafts, T or Y grafts from a pedicled mammary artery, or vein grafts anastomosed to arch vessels can be used (40). Patients with intracardiac thrombus or vegetations require aortic crossclamping before cardiac manipulation to avoid dislodging embolic material. When the left heart is open, large quantities of air can enter the left heart chambers and be difficult to remove. Flooding the field with carbon dioxide is one answer to the problem but is cumbersome and potentially dangerous to the surgical team (41). The advent of routine transesophageal echocardiography to detect and aid in air removal has made this adjunct less important (42).

In-depth or screen filters are essential for cardiotomy reservoirs, although washing cardiotomy blood is important because fat emboli are not effectively filtered (43). The efficacy of arterial line filters is controversial because screen filters with a pore size less than 20 μm cannot be used because of flow resistance across the filter. However, air and fat emboli can pass through filters, although 20-mm screen filters more effectively trap microemboli than larger sizes (44). The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group have published innovative techniques using small-pore venous reservoir and arterial line filters to eliminate microemboli generated in CPB circuits (45).

A technique for monitoring cerebral oxygen saturation by near-infrared spectroscopy has been widely used to avoid hypoxia during bypass. A randomized study demonstrated improved overall outcomes but no significant improvement in stroke incidence (46). This finding may indicate that maintenance of adequate cerebral oxygenation is a surrogate for overall adequate perfusion during bypass but has little effect on microembolic brain damage.

There are many surgeons who feel that off-pump surgery is safer than on-pump coronary bypass and many papers have been published with basically inconsistent results. Two smaller studies reached the conclusion that high-risk patients benefit disproportionately from off-">pump surgery (47,48). The only large trial that demonstrated superior results from off-pump coronary bypass surgery was a meta-analysis of 120,000 propensity-matched patients demonstrating highly statistically significant benefits in mortality and stroke (49). One year later a large database review found no advantage in any outcome measures for off-pump surgery (50). Until the results of a large prospective randomized trial are published, no firm conclusions can be made related to neuroprotection.

A similar statement can be made about pharmacologic neuroprotection during bypass. Despite many studies of a myriad of agents no definite, sustained improvement in outcome has been demonstrated.

PROGNOSIS

Patients with intraoperative stroke or who develop stroke symptoms in the first week after surgery often improve in direct relation to the lesion size and location on imaging studies. Neuropsychologic deficits that are present after 3 months are almost always permanent (51). Assessments after that time are confounded by development of new deficits, particularly in aged patients (52).

The difficulty of separating intraoperative brain injury from that which occurs in the early or late postoperative period has been recently addressed by a reanalysis of data published earlier. The authors tracked specific neuropsychological deficits, which persisted unchanged for 6 months (persistent deficits) and separated them from new deficits that appeared after surgery (53). Using this technique, it is possible to accurately measure surgical brain injury and design techniques to eliminate this important cause of morbidity. Late follow-up studies should include a control group with similar risk factors but not having cardiac operations (54). This technique demonstrated similar outcomes in surgical and nonsurgical controls at 3 years, putting to rest the previous fear that surgical patients had recurrent neurocognitive deficits and were thus at greater risk for poor long-term outcomes.

In a recent study, a group of surgical patients who were evaluated with pre- and postoperative neuropsychological studies had rigid control of postoperative cardiovascular risk factors (55). Later studies demonstrated no delayed or late cognitive decline offering hope that aggressive medical therapy can compliment skillful surgery in preventing neurological injury.

SUMMARY

Brain damage as a result of cardiac surgery is an unfortunate consequence of otherwise successful surgery and can result in significant disability. This review explains the techniques to measure brain damage and the mechanisms of injury. Techniques of avoiding injury are discussed and outcomes are presented. It is hoped that adoption of these measures will improve surgical outcomes and result in a better quality of life for our patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman S, Smith P, Treasure T, et al. Acute neuropsychological consequences of coronary artery bypass surgery. Curr Psychol Res Rev. 1987;6:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murkin JM, Stump DA, Blumenthal JA, et al. Defining dysfunction: Group means versus incidence analysis—A statement of consensus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:904–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selnes OA, Grega MA, Bailey MM, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes 3 years after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A controlled study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1885–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baird A, Benfield A, Schlaug G, et al. Enlargement of human cerebral ischemic lesion volumes measured by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moody DM, Bell MA, Challa VR, et al. Brain microemboli during cardiac surgery or aortography. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maragos PJ, Schmechel DE.. Neuron-specific enolase, a clinically useful marker for neurons and neuroendocrine cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1987;10:269–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmer DB, Cornwall EH, Landar A, Song W.. The S-100 protein family: History, function, and expression. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:417–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persson L, Hardemark HG, Gustafsson J, et al. S-100 protein and neuro-specific enolase in cerebrospinal fluid and serum: Markers of cell damage in human central nervous system. Stroke. 1987;18:911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnsson P, Blomquist S, Luhrs C, et al. Neuron-specific enolase increases in plasma during and immediately after extracorporeal circulation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RE, Hansson LO, Liska J, et al. The effect of cardiotomy suction on the brain injury marker S100 beta after cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:847–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Secco M, Edelman JJ, Wilson MK, et al. Serum biomarkers of neurologic injury in cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogue CW, Murphy SF, Schechtman KB, et al. Risk factors for early or delayed stroke after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:642–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, et al. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD study. ISPOCD investigators, International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet. 1998;351:857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones EL, Weintraub WS, Craver JM, et al. Coronary bypass surgery: Is the operation different today? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The TIME Investigators. Trial of invasive versus medical therapy in elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary artery disease (TIME): A randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;358:951–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tardiff BE, Newman MF, Saunders AM, et al. Preliminary report of a genetic basis for cognitive decline after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roach GW, Kanchugar M, Mangano CM, et al. Adverse cerebral outcomes after coronary bypass surgery: Multicenter study of perioperative ischemia research groups and the ischemia research and education foundation investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1857–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niles NW, McGrath PD, Malenka D, et al. Survival of patients with diabetes and multivessel disease after surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization. Results of a large regional prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goto T, Baba T, Yoshitake A, et al. Craniocervical and aortic atherosclerosis as neurologic risk factors in coronary surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wareing TH, Davila-Roman VG, Daily BB, et al. Strategy for the reduction of stroke incidence in cardiac surgical patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55:1400–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stump DA, Kon NA, Rogers AT, et al. Emboli and neuropsychologic outcome following cardiopulmonary bypass. Echocardiography. 1996;13:555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lata A, Stump D, Deal D, et al. Cannula design reduces particulate and gaseous emboli during cardiopulmonary bypass for coronary artery bypass grafting. Perfusion. 2011;26:239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones TJ, Stump DA, Deal D, et al. Hypothermia protects the brain from embolization by reducing and redirecting the embolic load. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1465. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold JP, Charlson ME, Williams-Russo P.. Improvement of outcomes after coronary artery bypass; a randomized trial comparing high verus low mean arterial pressure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:1302–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murkin JM, Farrar JK, Tweed WA, et al. Cerebral autoregulation and flow/metabolism coupling during cardiopulmonary bypass: The role of PaCO2. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helps SC, Parsons DW, Reilly PL, et al. The effect of gas emboli on rabbit cerebral blood flow. Stroke. 1990;21:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moody DM, Brown WR, Challa VR, et al. Efforts to characterize the nature and chronicle the occurrence of brain emboli during cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion. 1995;9:416–417. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook DJ, Oliver WC, Orsulak TA, et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass temperature, hematocrit, and cerebral oxygen delivery in humans. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1671–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi B, Brady K, Lee J, et al. Impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow during rewarming from hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass and its potential association with stroke. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nathan HJ, Wells GA, Munson JL, et al. Neuroprotective effect of mild hypothermia in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: A randomized trial. Circulation. 2001;104(Suppl I):I85–I91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downing SW, Edmunds LH Jr.. Release of vasoactive substances during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:1236–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinsfelt B, Ricksten SE, Zetterberg H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of brain injury, inflammation, and blood–brain dysfunction in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren JS, Ward PA.. The inflammatory response. In: Beutler E, Coller BS, Lichtman MA, et al. (eds.). Williams Hematology, 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:67. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fantone JC.. Cytokines and neutrophils: Neutrophil-derived cytokines and the inflammatory response. In: Remick DG, Friedland JS (eds.). Cytokines in Health and Disease, 2nd ed New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1997:373. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kincaid EH, Jones TJ, Stump DA, et al. Processing scavenged blood with a cell saver reduces cerebral lipid microembolization. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1296–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox T, Mitchell S.. Microemboli in our bypass circuits: A contemporary audit. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2009;41:31–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milson F, Mitchell S.. A dual-vent left heart deairing technique markedly reduces carotid artery microemboli. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murkin JM, Menkis AH, Downey D, et al. Epiaortic scanning significantly decreases cerebral embolic load associated with aortic instrumentation for CPB. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1796–1803. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammon JW, Stump DA, Butterworth JE, et al. Single cross clamp improves six month cognitive outcome in high risk coronary bypass patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundt TM, Barner HB, Camillo CJ, et al. Total arterial revascularization with an internal thoracic artery and radial artery T graft. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webb WR, Harrison LH, Helmcke FR, et al. Carbon dioxide field flooding minimizes residual intracardiac air after open heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1489–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallegos RP, Gudbjartsson T, Aranki S.. Mitral valve replacement. In: Cohn LH. (ed.). Cardiac Surgery in the Adult, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012:862–863. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padagachee TS, Parsons R, Theobold RG, et al. The effect of arterial filtration on reduction of gaseous emboli in the middle cerebral artery during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:647–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riley JB.. Arterial line filters ranked for gaseous micro-emboli separation performance: An in vitro study. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2008;40:21–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groom RC, Quinn RD, Lennon P, et al. Detection and elimination of microemboli related to cardiopulmonary bypass circuits. Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murkin JM, Adams SJ, Novick RJ, et al. Monitoring brain oxygen saturation during coronary bypass surgery: A randomized prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hannan EL, Wu C, Smith CL, et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary bypass graft surgery: Differences in short-term outcome and long-term mortality and need for subsequent revascularization. Circulation. 2007;116:1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puskas JD, Thourani VH, Kilgo P, et al. Off-pump coronary bypass disproportionally benefits high risk patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1142–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuss O, von Salviti B, Borgermann J, et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: A systematic review and metaanalysis of propensity score analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;82:1966–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moller CH, Penninga L, Wetterslev J, et al. : Off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting for ischaemic heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD007224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, et al. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary artery bypass grafting. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vermeer SE, Longstreth WT Jr, Koudstaal PJ.. Silent brain infarcts: A systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammon JW, Stump DA, Butterworth JE, et al. CABG with single cross clamp results in fewer persistent neuropsychological deficits than multiple clamp or OPCAB. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1174–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Selnes OA, Grega MA, Borowicz LM, et al. Cognitive outcomes three years after coronary bypass surgery: A comparison of on-pump coronary bypass surgery and nonsurgical controls. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1201–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mullges W, Babin-Ebell J, Reents W, Toyka KV.. Cognitive performance after coronary bypass grafting: A follow-up study. Neurology. 2002;59:741–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]