Abstract

Mitochondrial diseases are notoriously difficult to diagnose due to extreme locus and allelic heterogeneity, with both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes potentially liable. Using exome sequencing we demonstrate the ability to rapidly and cost effectively evaluate both the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes to obtain a molecular diagnosis for four patients with three distinct mitochondrial disorders. One patient was found to have Leigh syndrome due to a mutation in MT-ATP6, two affected siblings were discovered to be compound heterozygous for mutations in the NDUFV1 gene, which causes mitochondrial complex I deficiency, and one patient was found to have coenzyme Q10 deficiency due to compound heterozygous mutations in COQ2. In all cases conventional diagnostic testing failed to identify a molecular diagnosis. We suggest that additional studies should be conducted to evaluate exome sequencing as a primary diagnostic test for mitochondrial diseases, including those due to mtDNA mutations.

Keywords: Mitochondrial genome, Exome, Next-generation sequencing, Leigh syndrome, Homoplasmy, MT-ATP6, Lactic academia, Mitochondrial complex I, Inborn error of metabolism, CoQ10 deficiency, Molecular diagnostics

1. Introduction

Disorders of mitochondrial dysfunction, a group of disorders that display both clinical and genetic heterogeneities, develop as a result of dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and can be caused by mutations in any of over 900 genes in the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes [1]. Most mitochondrial diseases involve multiple organ systems and may present with prominent neurologic and myopathic phenotypes, some of which can present as life threatening medical crises. Mitochondrial disorders are commonly classified as clinical syndromes based upon characteristic constellations of clinical features. For example, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS, OMIM #540000) is a separate syndrome from myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF, #545000). Other kindred conditions are Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS, OMIM #530000), and Leigh syndrome (LS, OMIM #256000). However, due to significant clinical variability many individuals do not fit perfectly into one particular syndrome. Frequent features of mitochondrial disease are diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, proximal myopathy, ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia, sensorineural deafness, optic atrophy, pigmentary retinopathy and can exhibit central nervous system manifestations including seizures, encephalopathy, stroke-like episodes, ataxia, and spasticity.

Mitochondrial disorders may be caused by defects of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) or nuclear genome. mtDNA mutations are transmitted by maternal inheritance, whereas, nuclear gene mutations may be inherited in an autosomal recessive, dominant or X-linked manner [2]. The mitochondrial genome is a circular double stranded DNA of ~16,569 nucleotides that has 37 genes, encoding 13 essential subunits of the respiratory chain, 22 transfer RNAs, and 2 ribosomal RNAs [3]. Each human cell contains hundreds to thousands of copies of mtDNA. While most individuals carry identical copies of mtDNA (homoplasmy), some inherit more than one mtDNA type from their mother (heteroplasmy) and others may develop heteroplasmy secondary to a new mutation within the mtDNA. The ratio of heteroplasmic mtDNA types can vary among individuals within the same maternal lineage, and also among organs and tissues within the same individual [4]. At least 77 nuclear genes have been linked to mitochondrial diseases, but over 1000 genes are implicated in mitochondrial function, many of which may also cause clinical manifestations if defective [5]. Overall, a conservative estimate for the prevalence of all mitochondrial diseases is 1 in 5000 live births [6].

Given the clinical variability and large number of both nuclear and mitochondrial genes in which mutations can occur and result in disease make specific diagnoses of mitochondrial diseases at the molecular level challenging. Any possible inheritance pattern is possible, including autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, mitochondrial (maternal) or sporadic. In addition, there is pleiotropy, with the same mutation potentially exhibiting diverse phenotypes in different individuals, even within the same family. An ideal test for mitochondrial disease would include testing both the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes concurrently. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics recently released a policy statement that stated whole exome and genome sequencing should be considered in the clinical diagnostic assessment of patients when the disorder has a high degree of genetic heterogeneity [7]. Clearly, mitochondrial diseases fit this description. Accordingly, we report the use of exome sequencing using a commercially available exome kit without specific enrichment or amplification of the mtDNA to definitively diagnose one patient with Leigh syndrome (LS, OMIM #256000), two siblings with mitochondrial complex I deficiency (OMIM #252010), and one patient with coenzyme Q10 deficiency (OMIM #607426). In each of the cases presented herein, conventional molecular testing had failed to produce a molecular diagnosis. Furthermore, we demonstrate the ability to detect both homoplasmic and heteroplasmic variants in the mitochondrial genome from exome sequencing without specifically targeting the mtDNA.

2. Case presentations

2.1. CMH000067

The first case was a three year old female who was born to a 35-year-old female at 38.5 week gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery. Pregnancy and delivery were uncomplicated. Maternal serum screening was reportedly normal and an amniocentesis was declined. A level II ultrasound was performed and was reportedly normal. Family history was unremarkable and there is no known consanguinity. Growth parameters were appropriate for gestational age with a birth weight of 2580 g (approximately 5th percentile) and length of 48.26 cm (between the 10th and 25th percentiles). She passed her newborn hearing screen and was discharged from the hospital after two days. Shortly thereafter she was noted to have feeding difficulties due to a poor suck. She breast fed for two weeks, but had poor weight gain, requiring supplementation with formula. Breastfeeding was discontinued by six weeks of age; however, the infant continued to have difficulties with choking and irritability after eating. Anti-reflux medication was started at six months of age and used intermittently until nine months of age. At nine months of age the parents expressed concern over her development because she was not sitting unsupported. This child displayed severe growth retardation in weight, height and head circumference. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was conducted at 17 months of age, demonstrating symmetric high T2 signal and restricted diffusion in the bilateral caudate heads and putamen and double lactic peaks on magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). These findings were considered nonspecific but consistent with a possible mitochondrial disorder. Other diagnostic considerations included a multitude of metabolic disorders or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. At 20 months she was reevaluated by a geneticist and found to be able to stand and bear weight for about 30 s before falling down due to fatigue. Upon physical examination, she was noted to be the 10th percentile for weight, 5th percentile for height and 10–25th percentile for head circumference (Fig. 1). Other findings included soft, doughy skin and hypotonia (Fig. 1) with a normal response to tuning fork. Lab testing revealed elevated levels of lactic acid (3.0 mmol/L; reference range 0.7–2.1 mmol/L) and pyruvic acid (0.22 mmol/L, reference range 0.08–0.16 mmol/L), with a lactic acid to pyruvate ratio of 13.6 (normal is less than 20) and slight elevation of alanine (595 mcmol/L, reference range 143–439 mcmol/L) on her plasma amino acid profile suggestive of a disorder of energy metabolism. Multiple genetic tests for mitochondrial myopathies were unrevealing, including chromosome analysis (46, XX), arrayCGH microarray analysis, mitochondrial DNA sequencing for common tRNA mutations, as well as a next-generation sequencing panel for 24 nuclear genes for mitochondrial diseases performed at GeneDx (Supplement Table 1). Due to the numerous negative genetic tests previously conducted, and the large number of potential candidate genes remaining for a potential mitochondrial disorder, exome sequencing was considered the most cost-effective approach likely to reveal a causal mutation. At the time of enrollment in our study, at age three, severe growth retardation was still noted; weight was 11.7 kg (5th percentile), height was 89.1 cm (10th percentile), and head circumference was 45 cm (<2nd percentile), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Image of CMH000067.

2.2. CMH000254 & CMH000255

The female proband, CMH000254, was the product of a second pregnancy to a 21 year old female and 26 year male. At birth she was 2835 g (10th percentile) for weight and, 47.5 cm (14th percentile) for height. The pregnancy was complicated by tobacco exposure and hypertension that did not require medical treatment. Fetal movements were described as normal. Maternal serum screening and prenatal ultrasounds were without abnormality. The family history was remarkable for a male sibling, CMH000255, who died on day of life 3 with an undefined disorder associated with metabolic acidosis. The proband was born at 39 weeks by repeat Cesarean section and was found to be acidotic soon after birth. She was transferred from a local hospital to a regional hospital at 9 h of life, and to a tertiary care hospital at by 18 h of life for management of metabolic acidosis. Initial labs revealed an ammonia level of 29 mcmol/L (reference range 15–92 mcmol/L) and a lactic acid level of 11.9 mmol/L (reference range 0.7–2.1 mmol/L). Physical examination was remarkable for an average for gestational age infant female who was nondysmorphic but relatively edematous who responded slowly to stimulation. She appeared symmetric and proportionate. Her cranium was well shaped without frontal bossing. The fontanelles were open and somewhat wide, particularly the coronal and metopic sutures. There was periorbital edema but eye exam was otherwise unremarkable. No corneal clouding, cataracts or colobomata were appreciated. Ears were somewhat lowset but otherwise normal. Nasal tip was upturned. Palate was intact. Other pertinent findings included a somewhat deep sacral crease without dimpling, hair tufts or draining, a liver edge that was palpable at the right costal margin, normal external female genitalia, no limb length anomalies, somewhat redundant skin on the hands with deep creases and loose joints. Neurologic examination was remarkable for diffuse hypotonia, withdrawal response to stimuli without eye opening, biting rather than sucking oral movements and diminished Moro reflex without cry. An echocardiogram revealed a 3 mm patent ductus arteriosis with right to left flow during systole and left to right flow during diastole, suggestive of suprasystemic pulmonary artery pressure. The right ventricle was mildly dilated with mild to moderately depressed systolic function and there was moderate tricuspid regurgitation. There was a small secundum atrial septal defect versus a patent foramen ovale. Left ventricular systolic function was adequate. A head ultrasound revealed diffusely abnormal echogenicity throughout the brain and cerebellar parenchyma with diminished gray-white matter differentiation suggestive of cerebral edema. Bilateral intraventricular cysts or synechiae were also appreciated. A renal ultrasound was without abnormalities. Laboratory studies were remarkable for a sodium of 142 mmol/L (132–142 mmol/L), a potassium of 3.9 mmol/L (3.5–6.2 mmol/L), a chloride of 105 mmol/L (99–112 mmol/L), carbon dioxide of 7 mmol/L (18–29 mmol/L), an anion gap of 30 mmol/L (7–14 mmol/L), a calcium of 9.5 mg/dL (8.6–11.0 mg/dL) and glucose of 69 mg/dL. Blood urea nitrogen was not elevated at 3 mg/dL (5–20 mg/dL); however, creatinine was elevated at 0.77 mg/dL (0.06–0.64 mg/dL). Liver function tests were essentially normal as was a complete blood count. Notably, the infant was acidotic without significant response to bicarbonate with an initial arterial blood gas upon arrival with a pH of 7.25, a pCO2 of 64, a pO2 of 64 and a HCO3 of 9 with a base excess of −18.2. A lactic acid level was 24.7 mmol/L (0.7–2.1 mol/L) with a beta-hydroxybutyric acid level of 555.2 (0–269 mcmol/L) and an ammonia level of 25 (15–92 mcmol/L).

Lactic acid levels were followed sequentially and never decreased below 24.3 mmol/L. A lactic to pyruvic acid ratio was not initially available. Given the worsening of the lactic acid levels on dextrose and the concern about a possible defect of pyruvate catabolism in light of a metabolic acidosis without significant ketosis, lactic acidemia and normoglycemia, dextrose was removed from the IV fluids and riboflavin, biotin and carnitine were started. The differential diagnosis included disorders of pyruvate catabolism (pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency, pyruvate carboxylase deficiency) or a mitochondrial disease. While organic acidemias such as methylmalonic acidemia or propionic acidemia were considered, the clinical presentation without hyperammonemia was less consistent with such a disorder. The infant eventually required ventilatory support and had worsening of her lactic acidemia and metabolic acidosis despite provision of bicarbonate and intensive medical support. A repeat lactic acid with a concurrent pyruvic acid revealed a lactic acid level of 26.0 mmol/L with a pyruvic acid level of 0.34 mmol/L with a ratio of 76.5. Lactic acid levels continued to worsen and the decision was made to withdraw support. The infant expired at 54 h of life. An autopsy was declined; however, the patient and her parents were enrolled in an exome sequencing study at our institution. An archived DNA sample was obtained on her brother who had a very similar history and died at three days of life. Previous chromosome and microarray analysis of the deceased sibling were normal (Supplement Table 1).

2.3. CMH000036

The fourth case was a 2-month-old female delivered at 32 week gestation due to non-reassuring fetal heart tones. There was a prenatal history of severe oligohydramnios, maternal tobacco use, fetal intracranial calcifications and an intracranial cyst. At birth, APGAR scores were 8 and 8 at one and five minutes, respectively. A true umbilical cord knot was noted. Following delivery the infant developed respiratory distress requiring CPAP. The chest X-ray demonstrated cardiomegaly and hazy lung fields. The first arterial blood was remarkable for a pH of 7.07 and base excess of −16. She had a lactic acid level of 25 mmol/L and was started on a bircarbinate drip. Persistent metabolic acidosis, hyperglycemia, cardiomegaly, and worsening respiratory distress prompted transfer to our institution on day of life two. An echocardiogram demonstrated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with almost complete obliteration of the left ventricular cavity. A genetics consultation was obtained. Notable findings included a prominent occiput, 11 ribs, spade-shaped hands, externally rotated flat feet, and an anteriorly placed anus. A paternal history of fixed apical cardiac defect and thrombosis was noted, but felt to be unrelated to clinical presentation of the patient. An extensive metabolic work-up was conducted, including pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in fibroblasts, which was normal. The hospital course was complicated by persistent acidosis, respiratory failure, necrotizing enterocolitis, and encephalopathy. Despite extensive medical care the patient died at two months of multiorgan failure and was given a clinical diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of undetermined etiology. An autopsy without restrictions was performed within ten hours of death. Mitochondrial enzyme studies were performed post mortem on muscle in a clinical laboratory (CIDEM), revealing deficiency in complexes I and III that met a minor criterion for the diagnosis of a mitochondrial respiratory chain disorder. In addition, there was increased citrate synthase activity, suggestive of mitochondrial proliferation. Major autopsy findings included left side hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, chronic lung disease associated with prematurity and therapeutic ventilatory assistance, cholestatic liver disease probably associated to total parenteral nutrition, and chronic renal tubular disease suggestive of smoldering tubular necrosis. A detailed description of the autopsy findings is available in the Supplementary data. The underlying cause of death was reported as premature birth with neonatal diabetes mellitus syndrome and the immediate cause of death was chronic lung disease of prematurity and myocardial hypertrophy of different putative metabolic and nonmetabolic etiologies. The mechanism of death was multiorgan failure with a possible contributing condition of a persistent metabolic syndrome associated with mitochondrial dysfunction of unknown molecular cause. Multiple genetic tests for mitochondrial disorders were found to be unrevealing (Supplement Table 1).

3. Results

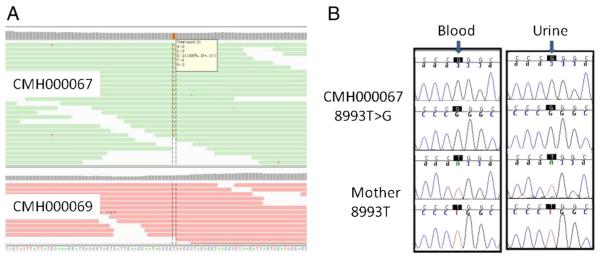

Exome enrichment and sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 was performed on CMH000067 and her two healthy parents (CMH000068 & CMH000069). The exome sequencing of CMH000067 generated a total of 7.7 gigabases of sequence resulting in a mean nuclear exome coverage of 59.6× and 86.0% of exome targets were covered at 16× or greater (Table 1), a suitable value for accurate heterozygous variant genotyping. Sequencing reads were aligned using GSNAP [8] and only unambiguous, uniquely aligned reads which aligned best to a single location in the nuclear or mitochondrial genome were evaluated for variant calls. Despite nuclear exome enrichment, the mitochondrial genome remained present and was sequenced concomitantly to an average depth of 25.5× resulting in 99.06% covered at 10× or greater (Table 1). The parental exomes were sequenced to >6 gigabases and had 88.05% and 88.52% of nuclear exome targets and 81.6% and 95.69% mtDNA covered at 10× or greater respectively (Table 1). A total of 105,487 variants including 10 mtDNA variants were discovered in CMH000069. Analysis revealed an apparently homoplasmic de novo mutation in mtDNA 8993T>G (c.467T>G, p.Leu156Arg) in the ATP synthase 6 gene (MT-ATP6, OMIM #516060; Fig. 2A). The variant was seen in 21 of 21 sequencing reads covering the base. This is a known disease causing variant responsible for 10–20% of Leigh syndrome (OMIM #256000) cases due to deficient activity of complex V (ATP synthase) in the electron transport chain, however previous clinical sequencing of mtDNA in this patient did not include MT-ATP6 [9]. A clinically validated restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay as well as capillary sequencing was used to confirm these findings on DNA from both blood and urine from the child (Fig. 2B). The 8993T>G mutation was not seen in maternal DNA from blood by next-generation exome sequencing, but coverage (15×) was likely insufficient for the detection of low levels of heteroplasmy. Although the 8993 mutation is usually well-represented in blood [10], we tested DNA isolated from both maternal urine and blood using capillary sequencing and PCR/RFLP analysis. Although the mutation was undetectable, these methods may fail to detect heteroplasmy of less than 10%. Consequently, as most cases of Leigh syndrome due to the 8993 mutation are maternally inherited, we cannot rule out that the mother may have a low level of heteroplasmy.

Table 1.

Exome sequencing summary.

| CMH000067 | CMH000068 | CMH000069 | CMH000254 | CMH000255 | CMH000256 | CMH000257 | CMH000036 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotides sequenced | 7,713,870,556 | 6,052,535,494 | 6,218,145,396 | 9,896,975,702 | 8,009,297,778 | 8,281,299,262 | 14,948,475,710 | 8,736,982,982 |

| Mean nuclear coverage | 59.6 | 48 | 47.5 | 69.3 | 56.2 | 59.1 | 106.6 | 71.9 |

| Median nuclear coverage | 50 | 40 | 40 | 53 | 42 | 46 | 83 | 61 |

| Nuclear target w/ 10× coverage | 90.56% | 88.05% | 88.52% | 89.87% | 87.48% | 88.91% | 92.56% | 84.60% |

| Mean mtDNA coverage | 25.5 | 13.4 | 18.2 | 17.6 | 59.4 | 19.9 | 31.8 | 30.1 |

| Median mtDNA coverage | 25 | 13 | 18 | 17 | 57 | 19 | 32 | 30 |

| mtDNA target w/ 10× coverage | 99.06% | 81.60% | 95.69% | 90.37% | 99.80% | 92.53% | 99.40% | 99.22% |

Fig. 2.

Next-generation sequencing results viewed in the Integrative Genome Viewer [1] of mtDNA–8993T>G, MT-ATP6 in CMH000067 and maternal sample CMH000069. MT-ATP6, 8993T>G is found in 21 of 21 reads (100% homoplasmy) in CMH000067 (A). Capillary sequencing confirmation of the mtDNA–8993T>G mutation in DNA isolated blood and urine from CMH000067 and her mother (B).

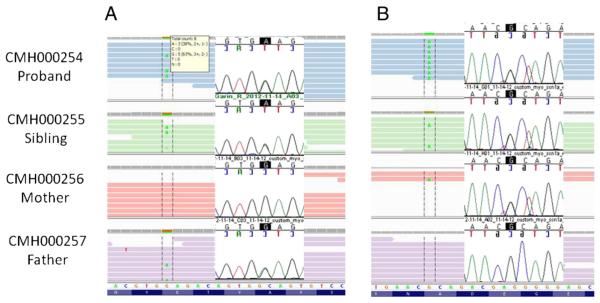

Exome sequencing was conducted on the proband (CMH000254), her deceased sibling (CMH000255), and both parents. All samples were sequenced to a depth of at least 8 gigabases resulting in greater than 87% of the targeted regions receiving 10× or greater coverage (Table 1). Less than 4% of the exome received 0× coverage. A total of ~3500 variants for each sample were characterized as category 1–3 by RUNES (Supplement Table 2, [11]). Briefly, category 1 variants are those previously described as disease causing, category 2 are those variants of the type likely to disrupt protein function and be disease causing if they are in a gene associated with disease and category 3 are variants of unknown significance that may or may not cause disease. Filtering variants to exclude those present at an allele frequency of > 1% in the Center for Pediatric Genomic Medicine internal database, which includes all variants ever detected from samples sequenced at the center and the corresponding frequency [11], resulted in nearly an 8-fold reduction in the number of variants (Table 2). Using a recessive inheritance model, variants were filtered to only include homozygous variants or genes in which there were two or more variants inherited on different alleles. Further filtering of variants was accomplished by limiting variants to those that were shared by both affected siblings and resulted in a total number of 29 variants to investigate in 18 genes (Table 3). Of the 18 genes only six were associated with disease in OMIM, with NDUFV1 being the only gene associated with metabolism. Both infants were found to be compound heterozygotes for two missense variants in the NDUFV1 gene c.736G>A, p.Glu246Lys (Fig. 3A) and c.349G>A, p.Ala117Thr (Fig. 3B). The parents each carry one variant, confirming they are present on opposite alleles. While neither variant has been previously reported, both affect highly conserved codons and are predicted to be damaging by in silico analysis. Furthermore, the Ala117Thr variant has been found by clinical testing in addition to a second novel missense mutation in a patient with confirmed mitochondrial disease (personal communication—Renkui Bai). This genotype was interpreted as being likely pathogenic and confirmed clinically by capillary sequencing (Figs. 3A & B). NDUFV1 encodes a 464 amino acid long protein that functions to release electrons from NADH via complex 1 of the electron transport chain, with resultant movement of the electrons to ubiquinone. The protein contains NADH, flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and iron–sulfur cluster binding sites that are predicted to be necessary for proper functioning of complex I. The Glu246Lys mutation occurs in the FMN binding site and could potentially be involved in binding of NADH [12].

Table 2.

Number of variants categorized as 1–3 by RUNES. category 1, previously described as disease causing; category 2, of the type likely to disrupt protein function, category 3, variant of unknown significance; AF, allele frequency in CMH internal database of greater than 1400 samples.

| Cat. 1 total |

Cat. 1 AF <1% |

Cat. 2 total |

Cat. 2 AF <1% |

Cat. 3 total |

Cat. 3 AF <1% |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMH000254 | 27 | 9 | 335 | 28 | 3113 | 393 |

| CMH000255 | 31 | 14 | 346 | 28 | 3039 | 402 |

| CMH000256 | 25 | 6 | 348 | 26 | 3170 | 412 |

| CMH000257 | 33 | 14 | 346 | 28 | 3053 | 400 |

| CMH000036 | 33 | 16 | 298 | 47 | 2911 | 727 |

Table 3.

Number of variants and (genes) within RUNES categories 1–3 consistent with compound heterozygous inheritance.

| Shared cat. 1 comp. het | Shared cat. 2 comp. het | Shared cat. 3 comp. het | Cat. 1 comp. het | Cat. 2 comp. het | Cat. 3 comp. het | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMH000254 | 2 (1) | 0 | 29 (18) | CMH000036 | 3 (3) | 13 (11) | 125 (53) |

| CMH000255 | 2 (1) | 0 | 29 (18) |

Fig. 3.

Next-generation and capillary sequencing of variant c.736G>A (p.Glu246Lys) inherited from father in CMH000254 (proband), CMH00255 (sibling), CMH000256 (mother) and CMH000257 (father) (A) and of variant c.349G>A (p.Ala117Thr) inherited from mother (B) viewed in the Integrative Genome Viewer [1,50].

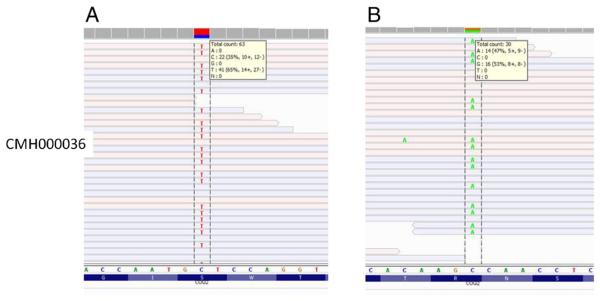

DNA isolated from peripheral blood cells from CMH000036 was enriched for the nuclear exome and sequenced to 8.7 gigabases, producing mean target nuclear exome coverage of 71.9× and mtDNA coverage of 30.1× (Table 1). A total of 150,740 nuclear and 32 mtDNA variants were found. Of these variants 3242 were classified as category 1–3 by RUNES [11] (Table 2). Applying a variant filter of less than 1% frequency in our internal database reduced the number of variants to 790. Due to lack of parental samples all genes with homozygous variants and genes with two or more variants were considered to be consistent with a recessive inheritance pattern, which limited the total variants to 141 in 67 genes. Of these variants, three were categorized 1 (Table 3) as previously reported disease causing mutations including c.437G>A (Ser146Asn) in coenzyme Q2 homolog, prenyltransferase (COQ2) [13]. The c.437G>A mutation was seen in 41 of 63 reads covering the position (Fig. 4A). Mutations in COQ2 have been reported to cause coenzyme Q10 deficiency (OMIM #609825) [13]. Further analysis of variants in COQ2 revealed a second variant c.1159C>T present in 14 of 30 sequencing reads (Fig. 4B), which causes an arginine to change to a premature stop codon at amino acid position 387 (Arg387X). Taken together, these variants in combination with the clinical phenotype are consistent with a diagnosis of coenzyme Q10 deficiency. In addition, we found a novel variant (3754C>A) in the mitochondrial genome-encoded NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1, MT-ND1 gene (Supplement Fig. 1). This variant was found in 8 of 36 sequence reads aligned to this nucleotide in the mitochondrial genome, implying ~22% heteroplasmy in peripheral blood. The variant was not found in more than 1400 other samples sequenced at CMH and was not reported in MitoMap [14], suggesting it to be a novel variant. Unfortunately, a sample from the mother could not be obtained. Subunit 1 is one of seven mtDNA encoded subunits included among the approximately 41 polypeptides of respiratory complex I [15]. Mutations in MT-ND1 cause a wide range of disorders, including Leber optic atrophy (OMIM #535000) [16,17], mitochondrial complex I deficiency (OMIM #252010) [18] and MELAS (OMIM #540000) [19]. Subsequent capillary sequencing of DNA isolated from the blood, lung, and heart confirmed the 3754C>A mutation and was estimated to be ~25% heteroplasmic on the basis of relative dideoxynucleotide peaks (Supplement Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Next-generation sequencing results viewed in the Integrative Genome Viewer [1] of variant c.437G>A (p.Ser146Asn) in COQ2 in CMH000036 found in 41 of 63 reads (A). Next-generation sequencing results of variant c.1159C>T (p.Arg387X) in COQ2 in CMH000036 found in 14 of 30 reads (B).

4. Discussion

Genomic medicine, empowered by whole exome and whole genome sequencing, has been widely heralded as potentially transformational for medical practice [20–23]. Many of the early successes of genomic medicine have come from monogenic disease discovery [24–26] and diagnosis [11,27,28], particularly in disorders that feature clinical and genetic heterogeneities. Mitochondrial diseases have both types of heterogeneity. Clinical features are often shared between multiple diseases making it difficult to arrive at a singular clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, mitochondrial disease may be inherited either as mutations in nuclearly encoded genes or in a homoplasmic or heteroplasmic manner with the respect to the mitochondrial genome. These attributes greatly complicate accurate diagnosis of individuals suspected to have one of these disorders. Herein we present four cases where exome sequencing yielded a molecular diagnosis after none were identified using conventional methods.

The diagnosis of Leigh syndrome (LS, OMIM #256000) in CMH000067 was made through the identification of an apparently homoplasmic known disease-causing mutation (8993T>G) in MT-ATP6. Although whole exome sequencing is not normally needed to detect this specific variant, the fact that MT-ATP6 gene sequencing had not been included in the more than 30 genes clinically sequenced exemplifies the difficulty in ordering clinical sequencing for mitochondrial disorders. LS is an early-onset progressive neurodegenerative disorder with a characteristic neuropathology consisting of focal, bilateral lesions in one or more areas of the central nervous system, including the brainstem, thalamus, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and spinal cord. The lesions are areas of demyelination, gliosis, necrosis, spongiosis, or capillary proliferation. Clinical symptoms depend on which areas of the central nervous system are involved. The most common underlying cause is a defect in oxidative phosphorylation [29]. About 50% of children with LS die by 3 years of age; however, clinical progression can be variable and long-term outcomes cannot be predicted based on genotype alone. For example, in individuals harboring the 8993T>G mutation, higher 8993G heteroplasmy is often associated with LS while moderate heteroplasmy is associated with less severe manifestations (weakness with ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP)) [30,31]. While there is no cure for LS, there are treatments that may improve cellular energetics. Obtaining a definitive molecular diagnosis allowed for improved medical management for this patient by the patient's treating physician, including the administration of sodium bicarbonate for chronic lactic acidemia, treatment of seizures with antiepileptic medications, and carnitine supplementation to aid excretion of abnormal byproducts of oxidative phosphorylation [32,33].

Respiratory chain deficiencies have been increasingly recognized in individuals presenting with a wide range of clinical problems, including encephalopathy, intransigent lactic acidemia and early death [34]. The electron transport chain consists of four membrane associated complexes that function to ultimately provide reducing substances for oxidative phosphorylation of ADP by ATP synthase (complex V). Approximately 30% of respiratory chain disorders are caused by deficiency of complex I, the largest complex of the respiratory chain [6,12]. Complex I is a multi-subunit complex of which 7 are encoded by mitochondrial DNA and at least 38 are encoded by nuclear DNA. It functions to channel electrons from NADH to ubiquinone and has, in addition to an NADH binding site, a flavin mononucleotide and Fe–S binding sites. NDUFV1 is a core subunit of complex I and is necessary for catalytic activity. To date, seventeen distinct mutations in the gene NDUFV1 have been described (Supplement Table 3) with clinical effects ranging from early infantile death to more classic features of Leigh syndrome. CMH000254 and CMH000255 presented with fulminate metabolic acidosis and lactic acidemia complicated by a neonatal encephalopathy which was highly suggestive of an inborn error of energy metabolism. Using this information to direct analysis of sequence data generated by exome sequencing, we were able to identify two mutations in the NDUFV1 gene, c.349G>A(A117T) and c.736G>A(Q246K), both of which are predicted to be deleterious by SIFT and/or PolyPhen2 conservation analysis models. These mutations have only been found in this family within the CMH variant database that houses data from over 1400 patients sequenced. These changes were confirmed by capillary sequencing in both affected infants and their parents. The mother is heterozygous for the c.349G>A(A117T) variant while the father carries the c.736G>A(Q246K) change, confirming they were present on opposite alleles in the affected offspring. While in vitro studies have not been completed, these variants are similar to other known mutations in the NDUFV1 gene. NDUFV1 is a core subunit in the N module of complex I. The N module functions as the electron input module and has flavin mononucleotide (FMN) as well as Fe–S clusters. This module binds NADH and oxidizes it, resulting in the transfer of electrons via FMN to the Fe–S clusters. Electrons are then transferred from the N module to the Q module which transfers them to ubiquinone. The complex also includes a P module which translocates protons across the membrane [35]. Several mutations (E214K, Y204C, C206G) have been predicted to possibly disrupt FMN binding with resultant decreased electron transfer, while others (A211V, A341V, R257Q, R386C, T423M) affect NADH-quinone oxidoreductase, chain F [35,36]. In our patients, one amino acid change is found proximal to residues felt to be involved in FMN binding while the second is near residues predicted to be involved in oxidoreductase activity. This could explain the more severe phenotype observed as failure of electron transfer and resultant deficiency of energy production in combination with diminished oxidoreductase activity.

In the last patient, CMH000036, we were able to diagnose the patient with coenzyme Q10 deficiency due to two mutations in COQ2. Similar to previous reports of COQ2 mutations our patient exhibited oligohydramnios and renal disease. In addition, we also discovered an apparently heteroplasmic variant in MT-ND1 (3754C>A). This variant was novel in our internal database of greater than 1400 sequenced individuals and has not been reported in MitoMap [14]. Previous case reports of patients with MT-ND1 mutations exhibit significant overlap with the clinical features seen in CMH000036 and are consistent with the severe manifestations [32,33]. Lacking viable tissue from the patient for functional studies or access to a maternal sample, we used the scoring system for determining the pathogenicity of mtDNA variants established by Mitchell and colleagues [37], which puts significant weight on heteroplasmy, conservation of the residue (Supplement Fig. 3), and demonstration of a biochemical defect in affected tissues. The 3754C>A variant scores in the 18–21 range, which is in the high possible/low probable range for being pathogenic. Additional functional studies, such as mitochondrial cybrid studies are needed to confirm the pathogenicity of this variant. As such, this variant is considered a variant of unknown significance. Importantly, it was detectable in the heteroplasmic state without specifically targeting the mitochondrial genome, highlighting the potential of exome sequencing to detect this type of pathogenic variant. We are unable to completely rule out the possibility that CMH000036 had two distinct disorders, CoQ10 deficiency and one of the disorders associated with MT-ND1 mutations such as Leber optic atrophy (OMIM #535000) [16,17], mitochondrial complex I deficiency (OMIM #252010) [18] or MELAS (OMIM #540000) [19]. However, we feel that it is highly likely due to the severity of the phenotype that the CoQ10 deficiency was the primary cause of the clinical phenotype caused by the mutations in the COQ2.

While the identification of pathogenic changes in these patients did not result in significant changes in management or outcome, in the future, early identification of such conditions will likely play a major role. In mitochondrial disorders in general, there is little other than anecdotal evidence to support the use of therapies such as carnitine, creatine, vitamins or bicarbonate. Confirming that individuals have primary mitochondrial disorders could be the first step in developing thoughtful clinical trials of these compounds to assess their efficacy. For example, knowing that complex V ATPase activity is diminished allows for the thoughtful addition of creatine as an alternative source for the generation of GTP. In other cases, early diagnosis will allow for parents to make educated decisions about painful, life-prolonging interventions that will ultimately prove futile. Knowing the recurrence risk is also important for those making reproductive choices including the possibility of the identification of carrier status in biologically related individuals, prenatal diagnosis in subsequent pregnancies or choosing different reproductive options, such as egg or sperm donor or adoption.

Several recent reports have demonstrated the efficacy of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for the diagnosis of mitochondrial disorders [27,38–40]. A panel that enriched ~1000 nuclear mitochondrial genes and the mt genome identified known disease causing mutations in 24% of patients and novel candidate mutations in an additional 31% of patients with mitochondrial phenotypes [27]. A separate study used a targeted approach to analyze nuclearly encoded mitochondrial genes and was able to identify several pathogenic mutations in known genes as well as identifying novel candidate mutations and genes, yet did not analyze the mtDNA in their study [38]. A benefit of using deep NGS of the mtDNA is the potential ability to detect lower levels of heteroplasmy and more accurately impute the percentage of heteroplasmy. To this end, using a targeted approach similar to Calvo et al. [27] allows for far greater depth of coverage (e.g. >1000×) and sensitivity as compared to using a standard exome enrichment (~50×), but requires the use of a custom targeted panel. Our findings clearly demonstrate the utility of using a standard exome kit for examining the mtDNA and discovery of both homoplasmic and heteroplasmic variants. However, in our experience there are multiple factors that affect the level of coverage obtained by target enrichment [22,24,41]. Specifically, we have observed, as reported by others, that there is a difference in the coverage of the mtDNA given the same amount of sequence using exome kits from different manufactures (unpublished data, [39]). For example, in our lab more consistent and deeper mtDNA coverage is obtained with Illumina exome kits as compared to NimbleGen or Agilent, using DNA isolated from cell culture versus blood, using smaller targeted panels of ~2 megabases that do not specifically target the mtDNA, and using different alignment algorithms (unpublished data). Consequently, we recommend that the coverage of the mtDNA and the sensitivity and specificity of mtDNA variant detection should be analyzed for each protocol and method used. In this study we specifically chose to use Illumina exome enrichment because using our methods we consistently obtain greater than 50× coverage of uniquely aligning reads with 6 gigabases or more of sequencing, which allows for analysis of both the nuclear and mtDNA genomes. It should be cautioned, however, that there are multiple limitations to next generation exome sequencing for clinical and molecular diagnostic purposes that we and others have reported [22]. For example, many bioinformatic pipelines are not well suited for detection of large insertions or deletions. The pipeline used in this manuscript cannot accurately detect insertions over 40 nts or deletions larger than 25 nts (Saunders et al., manuscript in prep). Copy number variations are also not automatically detected, but can be identified [41].

In conclusion, we show that the identification of nuclearly-encoded disease causing mutations and both homoplasmic and heteroplasmic mitochondrial variants may be detected using exome sequencing without specifically enriching for mitochondrial sequences. This is highly useful given the locus heterogeneity of mitochondrial disorders that extends to two separate genomes. In both of these cases, although mitochondrial disease was suspected, multiple diagnostic tests failed to identify the molecular basis of the disease. The broad net cast by exome and gene panel sequencing appears to be able to detect cases of nuclearly [27] and potentially mitochondrially-encoded diseases [39,40], and is likely to offer a higher yield than testing small panels of genes based on clinical or biochemical phenotype. We show in three unrelated families, that exome sequencing can indeed be effective; however, we propose that additional studies to examine the specificity and sensitivity in a larger number of samples are needed before it is considered as a primary diagnostic tool for patients with mitochondrial diseases.

5. Methods

5.1. Consent

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children's Mercy Hospital (CMH). Informed written consent was obtained from all adult subjects and parents of living children.

5.2. Targeted exome sequencing

The Center for Pediatric Genomic Medicine (CPGM) at CMH performed exome sequencing on a research basis. Isolated genomic DNA was prepared for sequencing using the Kapa Biosystems library preparation kit and 8 cycles of PCR amplification. Exome enrichment was conducted with the Illumina TruSeq Exome v1 kit (62.2 megabases) following a slightly modified version of the manufacturer recommended protocol. The enrichment protocol was modified to use the Kapa Biosystems PCR amplification kit for the post-enrichment amplification step to limit polymerase induced GC-bias [42]. Successful enrichment was verified by qPCR of 4 targeted loci and 2 nontargeted loci of the sequencing library pre- and post-enrichment prior to sequencing [41]. The enriched library was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 using v3 reagents and 1 × 101 basepair sequencing reads.

5.3. Next generation sequencing analysis

Sequence data was generated with Illumina RTA 1.12.4.2 & CASAVA-1.8.2, aligned to the human reference NCBI 37 using GSNAP [8] and variants were detected and genotyped using GATK [43]. The GATK Unified Genotyper discards reads with a low mapping quality score so that only reads that aligned unambiguously to a single place in the nuclear or mitochondrial genome were kept and analyzed [43]. We have previously reported a high concordance of variants detected with GSNAP/GATK and those detected using BWA/GATK [11]. Sequence analysis employed FASTQ files, the compressed binary version of the Sequence Alignment/Map format (bam, a representation of nucleotide sequence alignments) and Variant Call Format (VCF, a format for nucleotide variants). Variants were characterized with the CPGM's Rapid Understanding of Nucleotide variant Effect Software (RUNES v1.0) [11]. RUNES incorporates data from the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) software [44], and produces comparisons to NCBI dbSNP, known disease mutations from the Human Gene Mutation Database [45] and performs additional in silico prediction of variant consequences such as the effect of the variant on amino acid translation or splicing using ENSEMBL and UCSC gene annotations [46,47]. RUNES categorizes each variant according to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG's) recommendations for reporting sequence variation [48,49] as well as an allele frequency derived from CPGM's Variant Warehouse database [11]. Mitochondrial variants were further characterized by using mitoMap [13].

5.4. Capillary sequencing

Primers and PCR conditions are available upon request. PCR products were purified using Exo-Sapit (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH) according to manufacturer's instructions. Both the forward and reverse strands of the purified PCR product were sequenced using fluorescent dye-terminator sequencing. Sequencing reactions were purified using the BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Results were analyzed on an ABI 3130 analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence results were compared to published reference sequences using Sequencher 4.5 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI).

5.5. Data and materials

The genomic sequence data for this study have been deposited in the database dbGAP. Please contact authors for accession numbers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and families enrolled in this study. We also thank Dr. Renkui Bai of GeneDx for information sharing. A deo lumen; ab amicis auxilium.

Funding sources

This work was funded by the Marion Merrell Dow Foundation, the Patton Trust, and Children's Mercy Hospital.

Footnotes

Competing interests

NAM is a stockholder in Illumina, Inc., manufacturer of sequencing technologies used in this study. LDS is a member of Hunter's Outcome Survey Board and the Shire VPRIV advisory board, and has also received funding from Shire, Biomarin and Genzyme. Other authors disclose no competing interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualized and designed the study: SFK. Drafted the initial manuscript: DLD. Designed the bioinformatics tools, and coordinated bioinformatics efforts: NAM. Coordinated and supervised sample and clinical data collection, provided genetic counseling to the families, obtained consent: AMA, MS, LDS. Carried out the initial analyses: DLD, CJS. Reviewed data analysis: EGF. Was the physician-of-record: LDS. Undertook the exome sequencing: DLD, EGF. Developed clinical–pathological components of bioinformatic tools, and coordinated protocol implementation: SES. Reviewed and revised the manuscript: SFK, CJS, LDS, SES. Critically reviewed the manuscript: NAM, AMA, EGF, SES. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.04.013.

Contributor Information

Neil A. Miller, Email: nmiller@cmh.edu.

Andrea M. Atherton, Email: amatherton@cmh.edu.

Emily G. Farrow, Email: egfarrow@cmh.edu.

Meghan E. Strenk, Email: mestrenk@cmh.edu.

Sarah E. Soden, Email: ssoden@cmh.edu.

Carol J. Saunders, Email: csaunders@cmh.edu.

Stephen F. Kingsmore, Email: sfkingsmore@cmh.edu.

References

- [1].Chinnery PF. In: Mitochondrial Disorders Overview. Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP, editors. GeneReviews; Seattle (WA): 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thorburn DR, Dahl HH. Mitochondrial disorders: genetics, counseling, prenatal diagnosis and reproductive options. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;106:102–114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pakendorf B, Stoneking M. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2005;6:165–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Macmillan C, Lach B, Shoubridge EA. Variable distribution of mutant mitochondrial DNAs (tRNA(Leu[3243])) in tissues of symptomatic relatives with MELAS: the role of mitotic segregation. Neurology. 1993;43:1586–1590. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pagliarini DJ, Calvo SE, Chang B, Sheth SA, Vafai SB, Ong SE, Walford GA, Sugiana C, Boneh A, Chen WK, Hill DE, Vidal M, Evans JG, Thorburn DR, Carr SA, Mootha VK. A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell. 2008;134:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Skladal D, Halliday J, Thorburn DR. Minimum birth prevalence of mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders in children. Brain. 2003;126:1905–1912. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Michaelson JJ, Shi Y, Gujral M, Zheng H, Malhotra D, Jin X, Jian M, Liu G, Greer D, Bhandari A, Wu W, Corominas R, Peoples A, Koren A, Gore A, Kang S, Lin GN, Estabillo J, Gadomski T, Singh B, Zhang K, Akshoomoff N, Corsello C, McCarroll S, Iakoucheva LM, Li Y, Wang J, Sebat J. Whole-genome sequencing in autism identifies hot spots for de novo germline mutation. Cell. 2012;151:1431–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wu TD, Nacu S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:873–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Takahashi S, Makita Y, Oki J, Miyamoto A, Yanagawa J, Naito E, Goto Y, Okuno A. De novo mtDNA nt 8993 (T–> G) mutation resulting in Leigh syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;62:717–719. doi: 10.1086/301751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].White SL, Shanske S, McGill JJ, Mountain H, Geraghty MT, DiMauro S, Dahl HH, Thorburn DR. Mitochondrial DNA mutations at nucleotide 8993 show a lack of tissue- or age-related variation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1999;22:899–914. doi: 10.1023/a:1005639407166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Saunders CJ, Miller NA, Soden SE, Dinwiddie DL, Noll A, Alnadi NA, Andraws N, Patterson ML, Krivohlavek LA, Fellis J, Humphray S, Saffrey P, Kingsbury Z, Weir JC, Betley J, Grocock RJ, Margulies EH, Farrow EG, Artman M, Safina NP, Petrikin JE, Hall KP, Kingsmore SF. Rapid whole-genome sequencing for genetic disease diagnosis in neonatal intensive care units. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004041. 154ra135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Benit P, Chretien D, Kadhom N, de Lonlay-Debeney P, Cormier-Daire V, Cabral A, Peudenier S, Rustin P, Munnich A, Rotig A. Large-scale deletion and point mutations of the nuclear NDUFV1 and NDUFS1 genes in mitochondrial complex I deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:1344–1352. doi: 10.1086/320603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Diomedi-Camassei F, Di Giandomenico S, Santorelli FM, Caridi G, Piemonte F, Montini G, Ghiggeri GM, Murer L, Barisoni L, Pastore A, Muda AO, Valente ML, Bertini E, Emma F. COQ2 nephropathy: a newly described inherited mitochondriopathy with primary renal involvement. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;18:2773–2780. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].MitoMap A human mitochondrial genome database. 2012 Jun; www.mitomap.org (accessed)

- [15].Sharma LK, Lu J, Bai Y. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I: structure, function and implication in human diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:1266–1277. doi: 10.2174/092986709787846578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brown MD, Voljavec AS, Lott MT, Torroni A, Yang CC, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA complex I and III mutations associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Genetics. 1992;130:163–173. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brown MD, Yang CC, Trounce I, Torroni A, Lott MT, Wallace DC. A mitochondrial DNA variant, identified in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy patients, which extends the amino acid sequence of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:378–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hinttala R, Smeets R, Moilanen JS, Ugalde C, Uusimaa J, Smeitink JA, Majamaa K. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences in patients with isolated or combined oxidative phosphorylation system deficiency. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:881–886. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.042168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kirby DM, McFarland R, Ohtake A, Dunning C, Ryan MT, Wilson C, Ketteridge D, Turnbull DM, Thorburn DR, Taylor RW. Mutations of the mitochondrial ND1 gene as a cause of MELAS. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:784–789. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Green ED, Guyer MS. Charting a course for genomic medicine from base pairs to bedside. Nature. 2011;470:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature09764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Lupski JR, Gibbs RA. Human genome sequencing in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2012;63:35–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051010-162644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kingsmore SF, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Soden SE, Saunders CJ. Adopting orphans: comprehensive genetic testing of Mendelian diseases of childhood by next-generation sequencing. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2011;11:855–868. doi: 10.1586/erm.11.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kingsmore SF, Saunders CJ. Deep sequencing of patient genomes for disease diagnosis: when will it become routine? Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002695. 87ps23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Badolato R, Prandini A, Caracciolo S, Colombo F, Tabellini G, Giacomelli M, Cantarini ME, Pession A, Bell CJ, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Hateley SL, Saunders CJ, Zhang L, Schroth GP, Plebani A, Parolini S, Kingsmore SF. Exome sequencing reveals a pallidin mutation in a Hermansky–Pudlak-like primary immunodeficiency syndrome. Blood. 2012;119:3185–3187. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-404350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bilguvar K, Ozturk AK, Louvi A, Kwan KY, Choi M, Tatli B, Yalnizoglu D, Tuysuz B, Caglayan AO, Gokben S, Kaymakcalan H, Barak T, Bakircioglu M, Yasuno K, Ho W, Sanders S, Zhu Y, Yilmaz S, Dincer A, Johnson MH, Bronen RA, Kocer N, Per H, Mane S, Pamir MN, Yalcinkaya C, Kumandas S, Topcu M, Ozmen M, Sestan N, Lifton RP, State MW. M. Gunel, Whole-exome sequencing identifies recessive WDR62 mutations in severe brain malformations. Nature. 2010;467:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nature09327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bolze A, Byun M, McDonald D, Morgan NV, Abhyankar A, Premkumar L, Puel A, Bacon CM, Rieux-Laucat F, Pang K, Britland A, Abel L, Cant A, Maher ER, Riedl SJ, Hambleton S, Casanova JL. Whole-exome-sequencing-based discovery of human FADD deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Calvo SE, Compton AG, Hershman SG, Lim SC, Lieber DS, Tucker EJ, Laskowski A, Garone C, Liu S, Jaffe DB, Christodoulou J, Fletcher JM, Bruno DL, Goldblatt J, Dimauro S, Thorburn DR, Mootha VK. Molecular diagnosis of infantile mitochondrial disease with targeted next-generation sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003310. 118ra110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Licastro D, Mutarelli M, Peluso I, Neveling K, Wieskamp N, Rispoli R, Vozzi D, Athanasakis E, D'Eustacchio A, Pizzo M, D'Amico F, Ziviello C, Simonelli F, Fabretto A, Scheffer H, Gasparini P, Banfi S, Nigro V. Molecular diagnosis of usher syndrome: application of two different next generation sequencing-based procedures. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dahl HH. Getting to the nucleus of mitochondrial disorders: identification of respiratory chain-enzyme genes causing Leigh syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;63:1594–1597. doi: 10.1086/302169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].White SL, Collins VR, Wolfe R, Cleary MA, Shanske S, DiMauro S, Dahl HH, Thorburn DR. Genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis for the mitochondrial DNA mutations at nucleotide 8993. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:474–482. doi: 10.1086/302488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Uziel G, Moroni I, Lamantea E, Fratta GM, Ciceri E, Carrara F, Zeviani M. Mitochondrial disease associated with the T8993G mutation of the mitochondrial ATPase 6 gene: a clinical, biochemical, and molecular study in six families. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1997;63:16–22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Moslemi AR, Darin N, Tulinius M, Wiklund LM, Holme E, Oldfors A. Progressive encephalopathy and complex I deficiency associated with mutations in MTND1. Neuropediatrics. 2008;39:24–28. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Blakely EL, Rennie KJ, Jones L, Elstner M, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, White CB, Shield JP, Pilz DT, Turnbull DM, Poulton J, Taylor RW. Sporadic intragenic inversion of the mitochondrial DNA MTND1 gene causing fatal infantile lactic acidosis. Pediatr. Res. 2006;59:440–444. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000198771.78290.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vilain C, Rens C, Aeby A, Baleriaux D, Van Bogaert P, Remiche G, Smet J, Van Coster R, Abramowicz M, Pirson I. A novel NDUFV1 gene mutation in complex I deficiency in consanguineous siblings with brainstem lesions and Leigh syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2012;82:264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pagniez-Mammeri H, Loublier S, Legrand A, Benit P, Rustin P, Slama A. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency of nuclear origin I. Structural genes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.11.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pagniez-Mammeri H, Rak M, Legrand A, Benit P, Rustin P, Slama A. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency of nuclear origin II. Non-structural genes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mitchell AL, Elson JL, Howell N, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Sequence variation in mitochondrial complex I genes: mutation or polymorphism? J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:175–179. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vasta V, Merritt II JL, Saneto RP, Hahn SH. Next-generation sequencing for mitochondrial diseases: a wide diagnostic spectrum. Pediatr. Int. 2012;54:585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Picardi E, Pesole G. Mitochondrial genomes gleaned from human whole-exome sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:523–524. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Guo Y, Li J, Li CI, Shyr Y, Samuels DC. MitoSeek: extracting mitochondria information and performing high-throughput mitochondria sequencing analysis. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1210–1211. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bell CJ, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Hateley SL, Ganusova EE, Mudge J, Langley RJ, Zhang L, Lee CC, Schilkey FD, Sheth V, Woodward JE, Peckham HE, Schroth GP, Kim RW, Kingsmore SF. Carrier testing for severe childhood recessive diseases by next-generation sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001756. 65ra64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Quail MA, Otto TD, Gu Y, Harris SR, Skelly TF, McQuillan JA, Swerdlow HP, Oyola SO. Optimal enzymes for amplifying sequencing libraries. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:10–11. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, McKenna A, Fennell TJ, Kernytsky AM, Sivachenko AY, Cibulskis K, Gabriel SB, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Stenson PD, Ball EV, Howells K, Phillips AD, Mort M, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: providing a comprehensive central mutation database for molecular diagnostics and personalized genomics. Hum. Genomics. 2009;4:69–72. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Flicek P, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Brent S, Carvalho-Silva D, Clapham P, Coates G, Fairley S, Fitzgerald S, Gil L, Gordon L, Hendrix M, Hourlier T, Johnson N, Kahari AK, Keefe D, Keenan S, Kinsella R, Komorowska M, Koscielny G, Kulesha E, Larsson P, Longden I, McLaren W, Muffato M, Overduin B, Pignatelli M, Pritchard B, Riat HS, Ritchie GR, Ruffer M, Schuster M, Sobral D, Tang YA, Taylor K, Trevanion S, Vandrovcova J, White S, Wilson M, Wilder SP, Aken BL, Birney E, Cunningham F, Dunham I, Durbin R, Fernandez-Suarez XM, Harrow J, Herrero J, Hubbard TJ, Parker A, Proctor G, Spudich G, Vogel J, Yates A, Zadissa A, Searle SM. Ensembl 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D84–D90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dreszer TR, Karolchik D, Zweig AS, Hinrichs AS, Raney BJ, Kuhn RM, Meyer LR, Wong M, Sloan CA, Rosenbloom KR, Roe G, Rhead B, Pohl A, Malladi VS, Li CH, Learned K, Kirkup V, Hsu F, Harte RA, Guruvadoo L, Goldman M, Giardine BM, Fujita PA, Diekhans M, Cline MS, Clawson H, Barber GP, Haussler D, James Kent W. The UCSC Genome Browser database: extensions and updates 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D918–D923. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Maddalena A, Bale S, Das S, Grody W, Richards S. Technical standards and guidelines: molecular genetic testing for ultra-rare disorders. Genet. Med. 2005;7:571–583. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000182738.95726.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Richards CS, Bale S, Bellissimo DB, Das S, Grody WW, Hegde MR, Lyon E, Ward BE. ACMG recommendations for standards for interpretation and reporting of sequence variations: revisions 2007. Genet. Med. 2008;10:294–300. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b5cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.