Abstract

Background

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) can act as either a tumour promoter or suppressor by its inactivation depending on the cell type. There are conflicting reports on the roles of GSK-3 isoforms and their interaction with Notch1 in pancreatic cancer. It was hypothesized that GSK-3α stabilized Notch1 in pancreatic cancer cells thereby promoting cellular proliferation.

Methods

The pancreatic cancer cell lines MiaPaCa2, PANC-1 and BxPC-3, were treated with 0–20 μM of AR-A014418 (AR), a known GSK-3 inhibitor. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay and Live-Cell Imaging. The levels of Notch pathway members (Notch1, HES-1, survivin and cyclinD1), phosphorylated GSK-3 isoforms, and apoptotic markers were determined by Western blot. Immunoprecipitation was performed to identify the binding of GSK-3 specific isoform to Notch1.

Results

AR-A014418 treatment had a significant dose-dependent growth reduction (P < 0.001) in pancreatic cancer cells compared with the control and the cytotoxic effect is as a result of apoptosis. Importantly, a reduction in GSK-3 phosphorylation lead to a reduction in Notch pathway members. Overexpression of active Notch1 in AR-A014418-treated cells resulted in the negation of growth suppression. Immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that GSK-3α binds to Notch1.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates for the first time that the growth suppressive effect of AR-A014418 on pancreatic cancer cells is mainly mediated by a reduction in phosphorylation of GSK-3α with concomitant Notch1 reduction. GSK-3α appears to stabilize Notch1 by binding and may represent a target for therapeutic development. Furthermore, downregulation of GSK-3 and Notch1 may be a viable strategy for possible chemosensitization of pancreatic cancer cells to standard therapeutics.

Introduction

The 5-year survival for the patients with pancreatic cancer is less than 5% owing to the aggressiveness of the disease and the lack of effective therapies.1–5 It is estimated that the incidence of pancreatic cancer and mortality will be 48 960 and 40 560, respectively, in 2015.5 It is projected that by 2030, pancreatic cancer will likely be the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA.6 Limited treatment options, and success mandates the development of novel treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer. Notch1 signalling, a highly conserved pathway throughout the animal kingdom, plays an important role in cellular differentiation, proliferation and survival. Both the Notch1 receptor and its ligands (Delta1 and Jagged1, for example) are transmembrane proteins with large extracellular domains. Binding of the Notch ligand promotes two proteolytic cleavage events in the Notch receptor resulting in the release of the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD).7,8 The released NICD translocates to the nucleus and binds with the DNA-binding protein complex CSL [CBF1, Su (H) and LAG-1], and activates various target genes such as Hairy and enhancer of split (HES)-1, cyclin D1, survivin, etc.7,8 Activated Notch (NICD) in its free form is unstable and quickly degraded, which facilitates the regulation of Notch signalling. Increased expression of Notch receptors and their ligands has been detected in human pancreatic cancer tissues and cell lines.9–11 Inhibition of Notch1 or the Notch signalling pathway by Notch1 siRNA in pancreatic cancer cells enhanced chemosensitivity to gemcitabine.12 Unfortunately, clinical trials utilizing Notch pathway inhibitors in patients with solid tumours resulted in significant side effects. However, several clinical trials are underway based on the inhibition of the Notch pathway via antibody therapy or by gamma-secretase inhibitors (see review.13,14) Recently, we have reported on xanthohumol, a natural product from the hop plant, that reduced pancreatic cancer cell growth predominantly by reduction in Notch1.15 FOLFIRINIX (combinations of 5FU, leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine (Gem) with nab-paclitaxel treatment on a patient with metastatic pancreatic cancer showed clinically meaningful improvements.2,16–18 However, acquired resistance often develops after treatment. One cause of resistance to drug treatment in pancreatic cancer is an increase in nuclear transcription factor kB (NF-kB) promoter activity by Notch1.19

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) is a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase that exists mainly as α and β isoforms. GSK-3 plays an important role in diverse biological processes such as cell-cycle progression, differentiation and apoptosis.20,21 GSK-3 is normally active in cells and predominantly regulated through the inhibition of its activity by selective phosphorylation. Briefly, activation of GSK-3α and β is dependent upon the phosphorylation of residues Tyr279 and Tyr216, respectively. GSK-3 can act as either a tumour promoter or suppressor by its inactivation, depending on the cell type.22 For example, inactivation of GSK-3 by phosphorylation has been shown to inhibit the growth of various cancers such as neuroblastoma, pancreatic cancer, neuroendocrine cancers and, therefore, GSK-3 has a potential role in the treatment of cancer.23–27 It is not known, however, which isoform of GSK-3 regulates cancer cell proliferation. To date, there are conflicting and contradictory reports of the role of GSK-3 isoforms in the modulation of cell growth.28,29 Importantly, most studies conducted on GSK-3 have focused mainly on GSK-3β, and so the role of the other isoform (GSK-3α) is not clear. Furthermore, previous studies showed that GSK-3β can phosphorylate NICD and up-regulate NICD transcriptional activity by controlling NICD protein stability.30,31

In this study, the specific role of the GSK-3 isoform and the interaction to Notch1 in pancreatic cancer cells were investigated. AR-A014418 [N-(4-methoxybenzyl)-N′-(5-nitro-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)urea], an ATP-competitive and specific GSK-3 inhibitor, treatment reduced pancreatic cancer cellular growth. Also, the reduction of cellular growth of the pancreatic cancer cell lines by AR-A014418 was associated with a reduction in phosphorylation of GSK-3α compared with GSK-3β. Importantly, treatment resulted in a significant reduction in Notch1 protein suggesting that the phosphorylation of GSK-3α is required for its stability. A rescue experiment with ectopic expression of active Notch1 negated the growth suppression effect of AR-A014418 treatment. Furthermore, knock-down of the GSK-3 isoform individually indicated that the reduction in Notch1 is due to depletion of GSK-3α rather than GSK-3β. Finally, immunoprecipitation analysis suggested that Notch1 binds to GSK-3α.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human pancreatic cancer cell lines (AsPC-1, PANC-1, BxPC-3 and MiaPaCa-2) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Usually, the culture media was replaced every 2–3 days and the confluent cells were subcultured by splitting them at 1:5 ratios.

Reagents

AR-A014418 [N-(4-methoxybenzyl)-N′-(5-nitro-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)urea], 1-chloro-2,4-dimethylthylthiazol-2yl-2,5- dipheynltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The AR-A014418 was solubilized in DMSO at stock concentrations of 50 mM and diluted in the media when used for treatment. Antibodies against GSK-3α, GSK-3β, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Notch1 and β-catenin, were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and cleaved PARP was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Denvers, MA, USA), active GSK-3α/β (phosphorylation at 216 and 279) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Cellular proliferation

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and were treated in quadruplicates with different concentrations of AR-A014418 for 2 and 4 days as described.15 Cell proliferation/viability was measured using the colorimetric assay with MTT.24 Values were calculated to percentage inhibition relative to the vehicle control (0.1% DMSO).

Non- invasive real-time cellular proliferation assay

Using IncuCyte Live-Cell Imaging systems (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), the cellular proliferation of the pancreatic cancer cell lines was measured as previously described.15 Briefly, MiaPaCa-2, (1000 cells per well) and AsPC-1 (2000 cells per well) were plated onto a 96-well plate and incubated in an XL-3 incubation chamber maintained at 37 °C. After 12 h, the cells were treated with varying concentrations of AR-A014418 (0–50 μM) for up to 4 days. The cells were photographed every 2 h using a 10× objective for the entire duration of the incubation. Cell confluence was calculated using IncuCyte 2011A software and importantly the IncuCyte Analyzer provides real-time cellular confluence data based on segmentation of high-definition phase-contrast images. The cell proliferation was expressed as an increase in the percentage of confluence in 12-h intervals.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analyses were conducted essentially as described.24 Cells were lysed in the radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA; Thermo Fisher, Grand Island, NY, USA) buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (Sigma-Aldrich). Equal amounts of proteins were quantified using the bicinchonic method (BCA; Thermo Fisher) and analysed by SDS–PAGE (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) using a Trans-Blot (Bio-Rad) and analysed by specific antibodies as indicated in the experiments. The detection of immune complexes was conducted using chemiluminescence with an HRP antibody detection kit, and then images were taken using a Molecular Imager™ ChemiDoc XRS+ imager with image lab software (Bio-Rad).

Caspase-3 and -7 activities

The caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) kit was used to measure the cleaved caspase-3 and -7 activities from the lysates of cells treated with AR-A014418. Ten to 15 μg of protein samples in 25 μL total volume was mixed with an equal volume (25 μL) of Caspase-Glo reagent and incubated at room temperature in a white 96-well plate for 30 min. The luminescence was then measured using an Infinite M200PRO Microplate reader (TECAN, San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunoprecipitation

To determine the interaction of GSK-3 isoforms and Notch1 by binding, immunoprecipitation was carried out. Briefly, MiaPaCa-2 cell lysates (100 μg) were incubated with GSK-3α, GSK-3β, Notch1, or a non-specific antibody for 1 h in ice. Then agarose beads were added and incubated overnight in a rotator. The next day, lysates were washes three times, and the final pellet was dissolved in gel loading buffer and analysed by SDS–PAGE.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (anova) with Bonferroni's posthoc testing was performed using a statistical analysis software package (IBM SPSS Statistics version 22; SPSS Inc., New York, NY, USA). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were represented as ± the standard error.

Results and Discussion

AR-A014418 treatment reduced pancreatic cancer cells proliferation

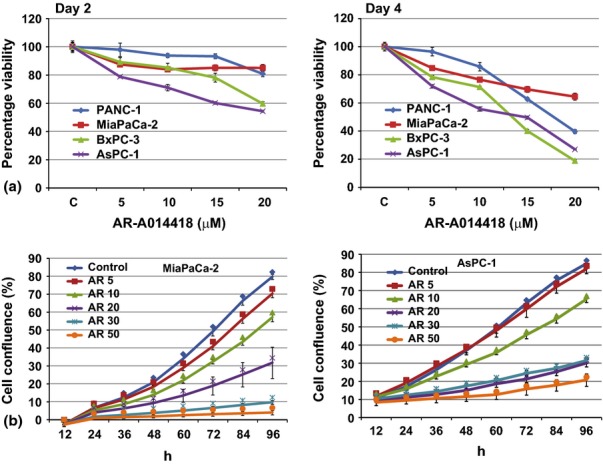

First, we determined the effect of GSK-3 inhibitor, AR-A014418, on cell viability in four pancreatic cancer cell lines. PANC-1, MiaPaCa-2, BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of AR (up to 20 μM) for 2 and 4 days and then the cellular viability was measured using the colorimetric (MTT) assay. Cell viability of pancreatic cancer cell lines was greatly reduced with increasing concentrations of AR (Fig. 1a). It had been reported that up to 25 μM concentrations of AR did not have any effect on the growth in the normal human mammary epithelial cell line HMEC and embryonic lung fibroblast cell line WI38.28 Therefore, the concentrations used in these experiments were more effective in pancreatic cancer cells. To further confirm our result, we have carried out a real-time non-invasive cellular proliferation assay using an incucyte analyser. Confluency was significantly reduced with increasing concentrations of AR in MiaPaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells tested (Fig. 1b). Our result confirmed the earlier report on growth suppression of BxPC-3 and Mia-PaCa-2 cells by AR-A014418 treatment.28

Figure 1.

The effect of AR-A014418 on pancreatic cancer cellular proliferation. (a) Colorimetric assay. Human pancreatic cancer cell lines were treated with AR-A014418 at indicated doses for 2 and 4 days and the cytotoxicity was measured using the MTT assay (n = 3; P = 0.05 at or above 10 μM concentrations for all cancer cell lines compared with the control. (b) The effects of AR-A014418 on pancreatic cancer cell proliferation in real-time. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of AR-A014418 and cell proliferation was monitored in real time with the continuous presence of the drug. The cells were photographed and the cell confluence was calculated using IncuCyte 2011A software. The changes in cell confluence are used as a surrogate marker of cell proliferation. Statistically significant (P < 0.05) growth suppressions were observed at or above 10 μM AR-A014418 compared with the control

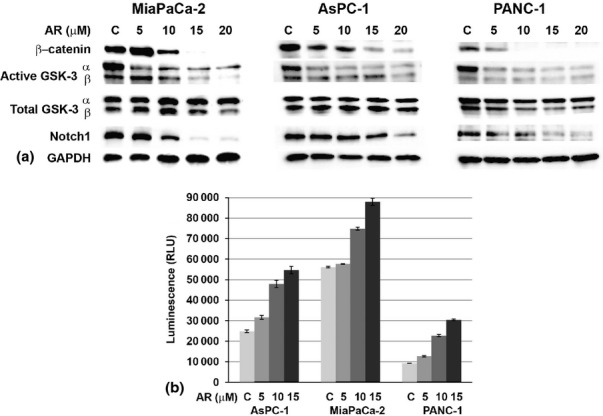

AR-A014418 reduced active GSK-3 phosphorylation and an associated reduction in Notch1 protein

AR-A014418 treatment has been shown to induce apoptosis and influences nuclear factor kB (NFkB) in pancreatic cancer cells.27,28 Recently, we have shown that AR-A014418 treatment significantly reduced the levels of active phosphorylation of GSK-3α more than GSK-3β in neuroblastoma.24 In addition, we showed that treatment reduced the levels of β-catenin in neuroblastoma.24 Therefore, we wanted to determine whether the effects of AR-A014418 are similar in pancreatic cancer cells. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we carried out Western blots analysis. As seen in Fig. 2a, treatment with AR-A014418 resulted in a decrease in β-catenin in all three cell lines tested. This decreased expression is associated with predominantly decreased phosphorylation of GSK-3α compared to GSK-3β with no change in the total GSK-3 expression (Fig. 2a). Most importantly, there was a significant reduction in the level of active Notch1 (Notch1 intracellular domain, NICD) protein. This is the first report on the effect of AR-A014418 treatment that reduces the level of active Notch1 protein. It is interesting because a recent report suggested that GSK-3β plays a key role in the regulation of NFkB and inactivation of GSK-3β would decrease the cellular proliferation and survival.26–28 Furthermore, in pancreatic cancer cells, NFkB activity is high and may lead to chemoresistance. Therefore, inhibition of NFkB activity is favourable to make pancreatic cancer cells sensitive to chemotherapeutic agents. Additionally, it has also been reported that there is a cross-talk between Notch1 and NFkB and downregulation of Notch1 by curcumin resulting in a reduction in NFkB activity in pancreatic cancer cells.32 Recently, we have observed that xanthohumol, a natural product, reduces Notch1 and decreases NFkB activity in pancreatic cancer cells.15 Ougolkov et al. have reported that GSK-3 inhibition resulted in reduced NFkB activity in pancreatic cancer cells.28 We predict that inactivation of GSK-3 leads to a reduction in Notch1 protein, and this resulted in reduced NFkB thereby inhibiting cellular proliferation. As shown in Fig. 2b, the treatment of AR-A014418 in pancreatic cancer cell lines resulted in increased cleaved caspase-3/7 indicating the induction of apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of AR-A014418 in pancreatic cancer cell lines. (a) The levels of β-catenin, active phosphorylated GSK-3, total GSK-3 and active Notch1 were analysed from lysates after 48 h of AR-A014418 treatment by Western analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (b) Caspase-3 and -7 activities were measured by the caspase-Glo3/7 assay. (n = 3; P < 0.05 at 10 and 15 μM treatment compared with the control in all cell lines tested)

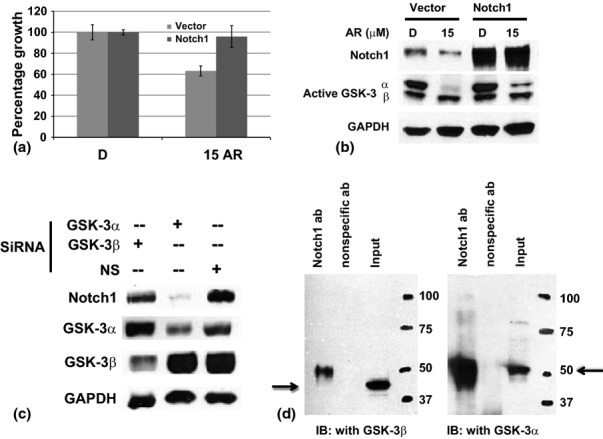

Forced overexpression of active Notch1 reversed the growth suppression effect of AR-A014418 in pancreatic cancer cells

Several studies have demonstrated the anti-proliferative effects of GSK-3 inhibitors including AR-A014418 on variety of cancer types, but the mechanism of action remains unclear.23–28,33,34 The observed reduction in cell proliferation and the associated reduction of the Notch1 protein level suggest that the Notch pathway inhibition may be important in AR-A014418 treatment. To examine whether the Notch1 pathway inhibition directly mediates growth suppression by AR-A014418, active Notch1 (NICD1) was overexpressed in MiaPaCa-2 cells, treated with AR-A014418 for 2 days, and then cell viability was measured. Notch1 overexpressed AR-A014418-treated MiaPaCa-2 cells and showed less growth suppression as compared with cells transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 3a) suggesting that inhibition of Notch1 is important for the growth suppression effect. Western blot analysis showed the presence of over expressed Notch1 protein (Fig. 3b). As predicted in the transfected empty vector, AR-A014418-treated cells showed a reduced expression of both Notch1 and active GSK-3α phosphorylation. Interestingly, we have observed there is a slight increase in GSK-3α phosphorylation in Notch1-transfected and AR-A014418-treated cells compared with the transfected empty vector and AR-A014418-treated cells (Fig. 3b lane 2 and 4). The reason for the increase is not known at this time. However, we speculate that the increase in Notch1 protects GSK-3α from AR-A014418 treatment by binding.

Figure 3.

Interaction of GSK-3 and Notch1. (a) The effect of Notch1 overexpression in the AR-A014418 treatment. Cells were transfected with Notch1 plasmid and treated with or without AR-A014418 for 4 days. The percentage of growth was measured by the MTT assay (n = 3; P = 0.05 at 4 day compared with the vector with AR-A014418 15 μM in MiaPaCa-2 cells tested). (b) Western analysis of the lysates from the parallel experiment as mentioned in (a), for Notch1 and active GSK-3 proteins. AR-A014418 treatment reduced the level of active Notch1 expression as well as active GSK-3α phosphorylation in MiaPaca-2 cells (lane 2). However, transfection of active Notch1 plasmid rescued the phosphorylation of GSK-3α in AR-A014418-treated cells (lane 4). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (c) Transfection of siRNA against GSK-3α resulted in a reduction in Notch1 level whereas GSK-3β and non-specific, no-target (NS) siRNA did not alter the levels of Notch1 protein in MiaPaCa-2 cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (d) MiaPaCa-2 cell lysates were immuoprecipitated with Notch1 antibody and then immunoblotted with either GSK-3α or GSK-3β to determine the binding ability to Notch1 protein. Non-specific antibody did not bind to GSK-3 whereas Notch1 binds to GSK-3α only

Interaction of GSK-3α and Notch1 protein

Because AR-A014418 treatment reduced Notch1 protein, and ectopic expression of Notch1 resulted in the negation of growth, we next investigated the interaction of Notch1 and GSK-3. To examine this, MiaPaCa-2 cells were genetically depleted of either GSK-3α or GSK-3β and the level of active Notch1 protein was examined. Depletion of GSK-3α lead to a significant decrease in active Notch1 compared with GSK-3β or non-specific, no target control transfected cells (Fig. 3c). This was further confirmed by immunoprecipitation analysis of GSK-3α or GSK-3β protein (Fig. 3d). As shown, immuoprecipitated with Notch1 antibody lysates detected GSK-3α protein by immunoblotted whereas GSK-3β did not, indicating that there is a binding interaction between Notch1 and GSK-3α in pancreatic cancer cells. In contrast, earlier studies showed that GSK-3β can phosphorylate NICD and up-regulate NICD transcriptional activity by controlling NICD protein stability.30,31 However, our results identified that GSK-3α is a predominant regulator of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and survival through the inhibition of Notch1 signaling. Furthermore, our results indicated that reduced Notch expression by inactivation of GSK-3 may lead to a reduction in NFkB activity and, therefore, providing new strategies for pancreatic cancer.

A subcutaneous tumour (pancreatic cancer or colon cancer) developed in mice treated with AR-A014418 resulted in a significant decrease in tumour volume without any adverse effects on the mice.26,27,35 These data suggested that AR-A014418 would be a novel class of therapeutic agent for cancer. The present studies indicated that AR-A014418 in combination with Notch inhibition may be more effective for the treatment of chemoresistant cancer. Therefore, future studies are warranted to determine the synergistic effect of inhibition of both GSK-3 and the Notch pathway.

Funding sources

This study was supported in part by the grants from the National Institute of Health R03 CA 155691 (M.K.), Institutional Research Grant # 86-004-26 from the American Cancer Society and MCW Cancer Center grant, The Medical College of Wisconsin Dean's Program Development and Froedtert Hospital Foundation (M.K and T.C.G).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Arteaga CL, Adamson PC, Engelman JA, Foti M, Gaynor RB, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2014. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:S1–S112. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy T, Gavoille C, Samalin E, Ychou M, Ducreux M. The role of the FOLFIRINOX regimen for advanced pancreatic cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:182–189. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martisian L, Aisenberg R, Rosenzweig A. 2012. The alarming rise of pancreatic cancer deaths in the United States: Why we need to stem the tide today. http://www.pancan.org/section_research/reports/pdf/incidence_report_2012pdf: Pancreattic cancer action network. Pancreatic action network.

- 4.Michl P, Gress TM. Current concepts and novel targets in advanced pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:317–326. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. 2015;2015:1–56. Cancer Facts And Figures. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. Tumor suppressor role of Notch-1 signaling in neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2007;12:535–542. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miele L, Golde T, Osborne B. Notch signaling in cancer. Currmolmed. 2006;6:905–918. doi: 10.2174/156652406779010830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du X, Zhao YP, Zhang TP, Zhou L, Chen G, Cui QC, et al. Notch1 contributes to chemoresistance to gemcitabine and serves as an unfavorable prognostic indicator in pancreatic cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:1688–1694. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukushima N, Sato N, Prasad N, Leach SD, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Characterization, of gene expression in mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas using oligonucleotide microarrays. Oncogene. 2004;23:9042–9051. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, Zechner U, Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, et al. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X, Wang YH, Wang ZQ, Cheng Z, Li Y, Hu JK, et al. [Down-regulation of Notch1 by small interfering RNA enhances chemosensitivity to Gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cells through activating apoptosis activity] Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban = J Zhejiang Univ Med Sci. 2014;43:313–318. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson ER, Lendahl U. Therapeutic modulation of Notch signalling–are we there yet? Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2014;13:357–378. doi: 10.1038/nrd4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espinoza I, Miele L. Notch inhibitors for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;139:95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunnimalaiyaan S, Trevino JG, Tsai S, Gamblin TC, Kunnimalaiyaan M. Xanthohumol-mediated suppression of Notch1 signaling is associated with antitumor activity in human pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1395–1403. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. Folfirinox versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. New Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, et al. Impact of folfirinox compared with gemcitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from the prodige 4/accord 11 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:23–29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hidalgo M, von Hoff DD. Translational therapeutic opportunities in ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Canc Res. 2012;18:4249–4256. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oswald F, Liptay S, Adler G, Schmid RM. NF-kappaB2 is a putative target gene of activated Notch-1 via RBP-Jkappa. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2077–2088. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali A, Hoeflich KP, Woodgett JR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: properties, functions, and regulation. Chemrev. 2001;101:2527–2540. doi: 10.1021/cr000110o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3beta) in tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCubrey JA, Davis NM, Abrams SL, Montalto G, Cervello M, Basecke J, et al. Diverse roles of GSK-3: tumor promoter-tumor suppressor, target in cancer therapy. Advanc Biol Reg. 2014;54:176–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adler JT, Cook M, Luo Y, Pitt SC, Ju J, Li W, et al. Tautomycetin and tautomycin suppress the growth of medullary thyroid cancer cells via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. Molcancer Ther. 2009;8:914–920. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter YM, Kunnimalaiyaan S, Chen H, Gamblin TC, Kunnimalaiyaan M. Specific glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition reduces neuroendocrine markers and suppresses neuroblastoma cell growth. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:510–515. doi: 10.4161/cbt.28015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunnimalaiyaan M, Vaccaro AM, Ndiaye MA, Chen H. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta, a downstream target of the raf-1 pathway, is associated with growth suppression in medullary thyroid cancer cells. Molcancer Ther. 2007;6:1151–1158. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ougolkov AV, Bone ND, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Kay NE, Billadeau DD. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity leads to epigenetic silencing of nuclear factor kappaB target genes and induction of apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 2007;110:735–742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Bilim VN, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, Billadeau DD. Aberrant nuclear accumulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in human pancreatic cancer: association with kinase activity and tumor dedifferentiation. Clincancer Res. 2006;12:5074–5081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Savoy DN, Urrutia RA, Billadeau DD. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta participates in nuclear factor kappaB-mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2076–2081. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson W, III, Baldwin AS. Maintenance of constitutive IkappaB kinase activity by glycogen synthase kinase-3alpha/beta in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8156–8163. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foltz DR, Santiago MC, Berechid BE, Nye JS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta modulates notch signaling and stability. Currbiol. 2002;12:1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song J, Park S, Kim M, Shin I. Down-regulation of Notch-dependent transcription by Akt in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1693–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Notch-1 down-regulation by curcumin is associated with the inhibition of cell growth and the induction of apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer. 2006;106:2503–2513. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenblatt DY, Ndiaye M, Chen H, Kunnimalaiyaan M. Lithium inhibits carcinoid cell growth in vitro. Amjtranslres. 2010;2:248–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ougolkov AV, Billadeau DD. Targeting GSK-3: a promising approach for cancer therapy? Futureoncol. 2006;2:91–100. doi: 10.2217/14796694.2.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shakoori A, Mai W, Miyashita K, Yasumoto K, Takahashi Y, Ooi A, et al. Inhibition of GSK-3Beta activity attenuates proliferation of human colon cancer cells in rodents. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1388–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]