Abstract

Background

Intraductal papillary neoplasms of the biliary tract (IPNB) and intracholecystic papillary neoplasms (ICPN) are rare tumours characterized by intraluminal papillary growth that can be associated with invasive carcinoma. Their natural history remains poorly understood. This study examines clinicopathological features and outcomes.

Methods

Patients who underwent surgery for IPNB/ICPN (2008–2014) were identified. Descriptive statistics and survival data were generated.

Results

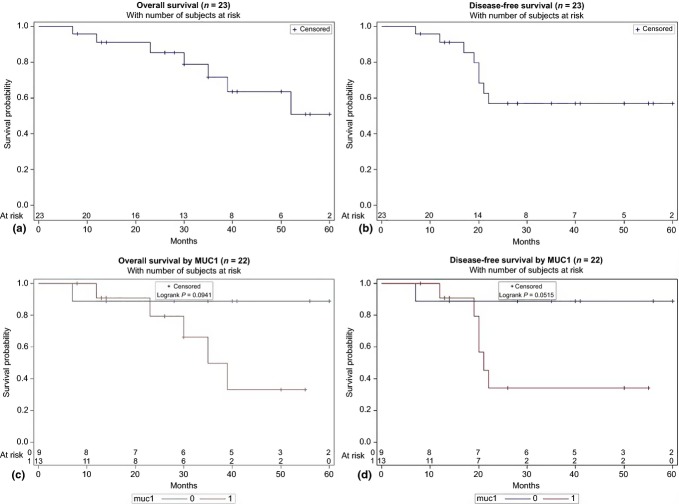

Of 23 patients with IPNB/ICPN, 10 were male, and the mean age was 68 years. The most common presentations were abdominal pain (n = 10) and jaundice (n = 9). Tumour locations were: intrahepatic (n = 5), hilar (n = 3), the extrahepatic bile duct (n = 8) and the gallbladder (n = 7). Invasive cancer was found in 20/23 patients. Epithelial subtypes included pancreatobiliary (n = 15), intestinal (n = 7) and gastric (n = 1). The median follow-up was 30 months. The 5-year overall (OS) and disease-free survivals (DFS) were 51% and 57%, respectively. Decreased OS (P = 0.09) and DFS (P = 0.05) were seen in patients with tumours expressing MUC1 on immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Conclusion

IPNB/ICPN are rare precursor lesions that can affect the entire biliary epithelium. At pathology, the majority of patients have invasive carcinoma, thus warranting a radical resection. Patients with tumours expressing MUC1 appear to have worse OS and DFSs.

Introduction

Intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CC) develop through a dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. Until recently, the nomenclature and criteria for the classification of biliary precursor lesions were not well established. At least two major precursor lesions have been associated with the development of invasive CC. The first is a microscopic lesion of flat or micropapillary dysplastic epithelium, biliary dysplasia or biliary intraepithelial neoplasia (BilIN).1,2 The second is an intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct, which is a macroscopic lesion, single or multiple along the biliary tract, characterized by intraluminal growth, prominent papillary proliferation of dysplastic epithelium with frequent intestinal metaplasia and mucin hypersecretion. These lesions were previously called papillomas, papillary adenomas, papillomatosis (when multiple) or mucin-secreting bile duct tumours. An intraductal papillary neoplasm of the biliary tract (IPNB) was recognized as a distinct pathological entity by the World Health Organization in 2010.3–8 IPNB has widely been considered to be analogous to an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas.4,5,7,9–11 Both IPNB and IPMN feature intraluminal growth, an association with mucin hypersecretion, and the same four histological subtypes have been described: pancreatobiliary, intestinal, gastric and oncocytic.9,12 The same tumour type occurring in the gallbladder is commonly referred to as intracholecystic papillary neoplasm (ICPN).13

While there is an increasing body of literature on IPNB and ICPN emerging from Asia, the North American experience remains limited. The largest North American series have identified 39 and 23 patients, respectively,11,14 and did not include cases of ICPN. From the Asian literature, it is believed that IPNB demonstrates a favourable prognosis compared with typical cholangiocarcinoma.7,15–17 This may be related to its intraluminal growth rather than a periductal infiltrating growth. Compared with the Asian experience18,19, the North American literature seems to demonstrate a higher proportion of invasive carcinoma at the time of surgical resection.11,14 The objective of this paper was to describe further the clinical and pathological characteristics of a cohort of North American patients with IPNB and ICPN.

Patients and methods

After approval from The Ottawa Health Science Research Ethics Board (20140648-01H), a computerized search was performed in the Anatomic Pathology archives. All cases between March 2008 and September 2014 of resected gallbladder, intrahepatic, hilar and extrahepatic bile duct tumours, cross-referenced with the words ‘cholangiocarcinoma’, ‘adenocarcinoma’, ‘intraductal’, ‘papilloma’, ‘papillomatosis’ or ‘papillary architecture’, were retrieved from the surgical pathology files. Pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, ampullary and periampullary tumours of uncertain origin, and cases with intraductal epithelial dysplasia/neoplasia without compelling evidence of intraductal mass formation were excluded.

All available tumour slides for the selected cases were reviewed by an expert pathologist in the liver, biliary and pancreatic disease (ECM). Tumours were reclassified as IPNB/ICPN with or without invasion according to the WHO classification.8 The tumours were evaluated for architecture (papillary, tubular or solid), epithelial type (intestinal, gastric, oncocytic or pancreatobiliary), grade of dysplasia, the presence and depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, lymph node metastasis and resection margin status.

The most representative tumour block from each case was subjected to immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with MUC1 (clone Ma695, dilution 1:100; Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), MUC2 (clone B306-1, dilution 1:50; ABCAM, Cambridge, MA, USA) and MUC5AC (clone CLH2, dilution 1:100; Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Over 20 human mucins (MUC1-MUC20) have been identified. Mucins can be broadly subdivided into two groups: proteins that are secreted and form extracellular gels (MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B and MUC6) and membrane-bound mucins (MUC1, MUC3 and MUC4).20 In this cohort, the expression of MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC was evaluated semiquantitatively. Tumours showing intense positive staining in more than 10% of tumour cells were considered positive, as previously reported.20

Demographic, clinical, operative and imaging data were retrieved retrospectively from patient records. Post-operative complications were also retrieved from patient records and classified using the Clavien–Dindo grading system. Survival data were obtained from clinic notes and, in cases where follow-up was conducted elsewhere, correspondence with the treating oncologist. Overall survival was measured from the date of surgical resection to the date of death. Patients still alive at the date of last clinical encounter were censored. Disease-free survival was measured from the date of surgical resection to the date of first recurrence or death from the disease. Patients were assumed to have died of disease unless they had clear evidence to the contrary. Patients still alive at the date of last clinical encounter and without evidence of disease recurrence were censored. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier estimate of survival, and comparisons were performed with the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Carry, NC, USA).

Results

Patients and pre-operative workup

Sixteen patients with IPNB and seven patients with ICPN were identified. Demographics and clinical presentations are detailed in Table 1. Most patients with IPNB presented in a manner typical of cholangiocarcinoma. Over two-thirds of patients had evidence of biochemical biliary obstruction, whereas less than half of patients had abdominal pain. All IPNB patients underwent either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pre-operatively. The majority of intrahepatic lesions were found in the left hemiliver (four out of five). All patients with IPNB went on to radical resection after cross-sectional imaging and, occasionally, endoscopic cytology/histology results. In contrast, patients with ICPN were more likely to present incidentally or with symptoms suggestive of cholelithiasis (6/7 patients). Specifically, two patients presented with epigastric pain suggestive of biliary colic, one with pancreatitis, and one with acalculous cholecystitis. One of the patients with biliary colic had a mass on imaging prior to surgery whereas the other three patients had no indication of having a gallbladder mass or polyp. Two additional patients were asymptomatic and were found to have a gallbladder mass or polyp incidentally. One patient presented with an abdominal mass on examination. For both IPNB and ICPN, serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) was not routinely assessed during the pre-operative work-up, but was used primarily for follow-up in select patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 23)

| Variable | IPNB (n = 16) | ICPN (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 70.1 ± 9.6 | 64.1 ± 12.9 |

| Male | 9 | 1 |

| Presentation | ||

| Jaundice | 9 | 0 |

| Abdominal Pain | 6 | 4 |

| Palpable mass | 0 | 1 |

| Incidental finding on imaging | 1 | 2 |

| Elevated AST/ALT | 10 | 1 |

| Elevated ALP | 11 | 0 |

| Pre-operative imaging | ||

| Ultrasound | 5 | 7 |

| CT scan | 13 | 4 |

| MRI | 12 | 2 |

| ERCP | 11 | 0 |

| EUS | 3 | 0 |

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CT, computed tomography; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; ICNB, intracholecystic papillary neoplasm; IPNB, intraductal papillary neoplasm of the biliary tract; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; n, number of patients; SD, standard deviation.

Surgical and pathological data

Surgical and pathological details are presented in Table 2. Pre-operative tissue diagnosis was attempted as part of the pre-operative workup in 10 patients with IPNB, whether by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) brushings, ERCP biopsy of a visible duodenal tumour or by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) fine-needle aspiration. Despite the final pathology results of microinvasive or invasive carcinoma in all patients with IPNB, only 2/10 pre-operative histology/cytology specimens were initially consistent with invasive malignancy.

Table 2.

Surgical and pathological characteristics

| Variable | IPNB (n = 16) | ICPN (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomic location | ||

| Left intrahepatic bile ducts | 4 | N/A |

| Right intrahepatic bile ducts | 1 | N/A |

| Liver hilum | 3 | N/A |

| Common bile duct | 8 | N/A |

| Pre-operative histology/cytology (n = 10) | ||

| Negative | 2 | N/A |

| Cytologic atypia | 1 | N/A |

| Suspicious for malignancy | 1 | N/A |

| High grade dysplasia | 4 | N/A |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 | N/A |

| Surgery performed | ||

| Left hepatectomy | 4 | |

| Segmental resection | 2 | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 5 | |

| Choledochectomy | 5 | |

| Lap cholecystectomy | 3 | |

| Open cholecystectomy | 1 | |

| Open cholecystectomy + liver wedge | 3 | |

| R0 resection | 12 | 7 |

| R1 resection | 4 | 0 |

| Epithelial subtype | ||

| Pancreatobiliary | 10 | 5 |

| Intestinal | 6 | 1 |

| Gastric | 0 | 1 |

| Mean tumour size (cm ± SD) | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 7.3 |

| Non-invasive | 0 | 3 |

| Microinvasion (<5 mm) | 4 | 2 |

| Invasion (>5 mm) | 12 | 2 |

| T stage | ||

| Tis | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 7 | 1 |

| 2a | 7 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 |

| N stage | ||

| X | 4 | 3 |

| 0 | 8 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Lymphovascular Invasion present | 6 (n = 15)b | 3 (n = 6) |

| Perineural Invasion Present | 6 (n = 13) | 0 (n = 5) |

Combines T2, T2a, T2b (each anatomic location has unique T staging).

not all pathology reports commented on lymphovascular or perineural invasion.

cm, centimetre; mm, millimetre; n, number of patients; SD, standard deviation.

All three patients with ICPN who presented with pain and did not have a mass on imaging went on to have a cholecystectomy. All three had carcinoma in situ on final pathology. One asymptomatic patient with a gallbladder polyp went on to laparoscopic cholecystectomy and was found to have a T3 carcinoma with negative margins. He declined further liver surgery. All three other ICPN patients who had either a palpable mass or mass on pre-operative imaging were considered to have gallbladder cancer and went on to have a cholecystectomy and liver resection. Among cases of ICPN, invasive cancer was seen in three of the five tumours with a pancreatobiliary subtype, and the one with a gastric subtype. The ICPN tumour with an intestinal subtype was non-invasive.

An R0 resection was achieved for all patients with ICPN and 12/16 patients with IPBN. Among the four patients with R1 resections, two patients had false-negative intra-operative frozen section bile duct margin analyses, one was unfit for more extensive radical resection, and one had intraductal tumour infiltration within the remnant liver.

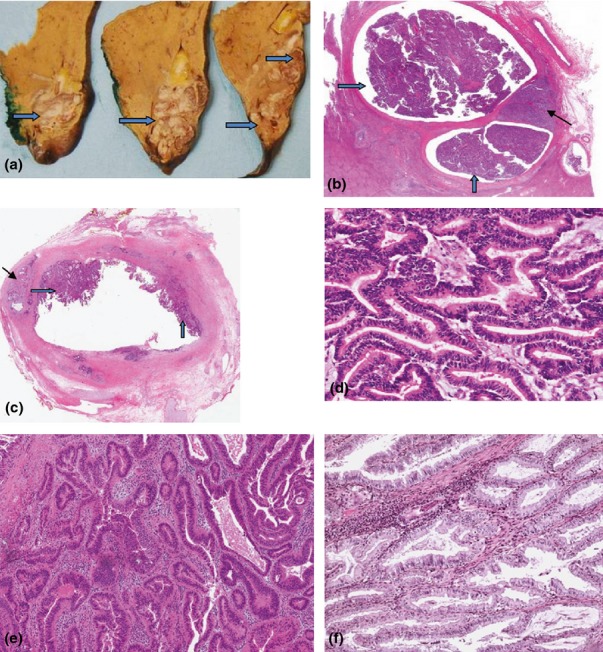

After pathological review for this work, 9/23 tumours were re-classified as IPNB/ICPN with or without invasion. Original reports included terms such as ‘papillary adenoma‘, ‘villous adenoma‘, ‘billiary papillomatosis‘ or ‘papillary differentiation‘. All included tumours showed a visible intraluminal growth (Fig. 1a) with papillary fronds showing delicate fibrovascular cores, lined by dysplastic epithelium (Fig. 1b, c). The most common histological subtype was pancreatobiliary (Fig. 1d), followed by an intestinal type (Fig. 1e) and a single tumour with a gastric phenotype (Fig. 1f). No tumour showed oncocytic features.

Figure 1.

(a) Liver left hepatectomy surgical resection specimen, showing a large papillary tumour filling the dilated intrahepatic bile ducts (thick arrows). (b) Tumour depicted in (a), showing the intraductal papillary neoplasm (IPNB) that fills the bile duct lumen and spreads along the biliary tree (thick arrows). An area of invasive adenocarcinoma into the liver parenchyma is noted, tubular type, poorly differentiated (thin arrow). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 2× magnification. (c) IPNB, common bile duct (thick arrows). Invasive adenocarcinoma is present, tubular type, invading the duct wall into the periductal adipose tissue (thin arrow). H&E stain, 2× magnification. (d) IPNB, pancreatico-billiary type. Tumour cells resemble biliary or pancreatic epithelium, are composed of columnar cells or low cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and round nuclei. H&E stain (200x). (e) IPNB, intestinal type. Tumour cells resemble intestinal adenoma or adenocarcinoma and are characterized by stratified tall columnar cells with some goblet cells. H&E stain (200x). (f) IPNB, gastric type. Tumour cells resemble gastric epithelium and are composed of columnar cells with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin. H&E stain (200x)

MUC1 was expressed in the luminal border and cytoplasm of cancer cells. MUC2 and MUC5AC were mainly expressed in the cytoplasm of tumour cells. MUC1 was expressed predominantly in the pancreatobiliary subtype, whereas the intestinal type showed constant expression of MUC2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Immunohistochemical characteristics of IPNB/ICPN (n = 22)

| Epithelial subtype | MUC1 | MUC2 | MUC5AC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatobiliarya | 11/14 | 2/14 | 8/14 |

| Intestinal | 2/7 | 7/7 | 4/7 |

| Gastric | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 |

| Total | 13/22 | 9/22 | 13/22 |

One specimen was not available for immunohistochemical profiling.

n, number of patients.

Outcomes

Seven patients experienced a post-operative complication (Clavien–Dindo grade 2 or higher), of which 3 patients had grade 3a complications. These included three cases of percutaneous drain insertion for a pancreatic fistula (n = 1) and bile leaks after a hepaticojejunostomy (n = 2). Grade 2 complications included three cases of antibiotics therapy for small undrained collections and one case of a blood transfusion. There were no complications requiring intensive care, and no mortalities.

Nine of the sixteen patients with IPNB underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, most commonly gemcitabine and cisplatin. One out of seven ICPN patients underwent adjuvant chemotherapy.

The median follow-up of patients was 30 months. There were seven patients who developed a recurrence of cancer: four with intrahepatic metastases, one with distant metastases, and two with both local recurrence and distant metastases. Five of the recurrences occurred in patients with distal extrahepatic primary cancers, and two in patients with gallbladder lesions. The furthest recurrence from the time of surgery was 22 months. Among patients with recurrence, six died, and one additional patient died without evidence of disease recurrence.

The OS at 3 and 5 years was 71% and 51%, respectively. Disease-free survival was 57% at both 3 and 5 years. There was no significant difference in OS and DFS for an R1 resection (P = 0.20 and 0.37) and epithelial subtype (P = 0.62 and 0.34). Similarly, there was no difference in OS or DFS when comparing micro-invasive and invasive tumours (P = 0.91 and 0.73). Patients with tumours expressing MUC1 demonstrated a decreased OS (P = 0.09), and DFS (P = 0.05). No other immunohistochemical markers were associated with prognosis. Figure 2 displays the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS and DFS for all 23 patients, and for the comparison of patients with and without expression of MUC1.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for (a) overall survival, (b) disease-free survival, (c) overall survival with/without MUC1, and (d) disease-free survival with/without MUC1

Discussion

The present study describes the clinical and pathological characteristics of patients undergoing surgery for IPNB and ICPN. It adds to a relatively limited body of literature on this topic, particularly in North America.

The current paper demonstrates that patients with IPNB or ICPN tend to present similarly to patients with typical cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer, albeit with occasional abdominal pain. Usually, the diagnosis of IPNB/ICPN was not established until the final surgical specimen is reviewed. The use of pre-operative endoscopic histology/cytology was not particularly reliable in establishing a diagnosis of malignancy (2/10), possibly owing to limited foci of invasive disease. At final pathology, the rate of invasive cancer amongst patients with intrahepatic, hilar, or distal extrahepatic IPNB was 100%, whereas that with ICPN of the gallbladder was 57%. This high rate of invasive disease among patients with IPNB is consistent with other North American papers but is higher than most Asian series.18,19 The discrepancy in the rates of invasion between the two continents is not entirely understood. Hepatolithiasis and liver fluke infection have been identified as risk factors among Asian patients,4,9,10,18,21,22 which may hint at a difference in pathophysiology. It may also explain the overall increased burden of disease in Asia. Earlier diagnosis or genetic differences may also play a role. At least one other series has noted that ICPN was more common in Asia, whereas a gallbladder lesion from flat dysplasia was more frequent in the West.23 Consistent with other series,4,7,14,19,24 the current study found the majority (80%) of intrahepatic IPNBs to be within the left hemiliver.

As described earlier, IPNB/ICPN is a precursor lesion to invasive cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma that is now considered distinct from the more common BilIN.8 IPNB/ICPN leads to macroscopically visible intraluminal lesions, whereas BilIN is typically ‘flat‘ and macroscopically non-tumour forming.8,25 When associated with BilIN, invasive carcinoma usually demonstrates a desmoplastic stromal reaction and tubular pattern.25 In contrast, IPNB/ICPN, which accounts for 10–15% of biliary tumours, lead to biliary or cholecystic luminal papillary tumour growth.25 As a result of tumour filling (with or without mucin), the latter leads to cystic or fusiform dilation of the bile duct.25 These lesions appear to be more common in the extrahepatic biliary tree (2:1), although they can be found synchronously in both the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts.25 IPNB/ICPN would also appear to be much more commonly associated with early symptoms of intermittent pain, jaundice or cholangitis.

Both IPNB and ICPN were included in the present study, as the pathophysiological process of papillary tumour growth within the biliary lumen appears to be the same for both tumour types.8,13 Clinically and anatomically, however, IPNB and ICPN behave differently in terms of presentation and surgical management. For this reason, both tumours were divided when describing presentation, management and outcomes. Furthermore, this is particularly relevant as the description of ICPN in the literature is in its infancy.13,23,26 The definition, described by Adsay et al.13, is of an exophytic intramucosal gallbladder mass greater than 1 cm and composed of dysplastic cells forming a lesion distinct from the neighbouring mucosa. The current paper represents one of the first surgical series to describe gallbladder lesions using this system.

In terms of epithelial subtypes, IPNB tumours demonstrated only pancreatobiliary and intestinal, with a slightly higher prevalence of pancreatobiliary. This is similar to other published reports,11,14 although gastric and oncocytic subtypes were also seen in small numbers. ICPN tumours, which were not included in the other North American series, also demonstrate mostly a pancreatobiliary subtype. This series found no cases of an oncocytic epithelial subtype.

The 5-year OS and DFS for this series were 51% and 57%, respectively, and did not differ significantly between the patients with IPNB and ICPN. This is similar to the 62 month OS previously reported,14 and slightly higher than the 38% 5-year OS reported by Barton et al.11 All of these data indicate that IPNB may confer an improved prognosis when compared with typical cholangiocarcinoma, as suggested in the Asian literature. That being said, it remains unclear whether this observation is related to an earlier presentation for most patients or whether, these tumours truly have a better biological prognosis, stage for stage. Furthermore, the present study adds to previously published evidence that MUC1 immunohistochemical staining is a poor prognostic marker in IPNB.14 MUC1 was the only factor that showed a statistically significant difference when comparing survival curves. An increased depth of invasion and R1 resection, both well-established negative prognostic factors in surgical oncology, did not reach statistical significance for OS and DFS.

Interestingly, all five patients with IPNB who experienced disease recurrence were among those with distal extrahepatic bile duct primary tumours. As no patients in the intrahepatic or hilar groups had a recurrence, comparison of survival curves or univariate analysis is not appropriate as there were no events. An increased risk of recurrence has not been associated with the anatomical location in other papers, and it is difficult to draw any conclusions from such a small sample.

It has been suggested from the Asian literature that pre-operative cholangioscopy and an intra-operative frozen section be more routinely used in patients with IPNB.4,10 The hypothesis being that with IPNB's intraluminal growth, these modalities may better delineate the extent of disease, and increase the likelihood of an R0 resection. Given that the majority of patients in the North American setting do not have an established pre-operative diagnosis of IPNB, this may not prove feasible. Further research on the utility of these tools in the setting of IPNB is required. A pre-operative cholangioscopy was not performed on any of the patients in this series, and an intra-operative frozen section was used at the surgeon's discretion. At least two patients had false-negative frozen sections, leading to R1 resection.

The major strength of this paper is the contribution of clinical and pathological data about patients with a disease that is poorly described in North America. To date, only two other papers have described a series of patients this large. The median follow-up of 30 months is robust, and the patient population is recent. Furthermore, it is only the second North American paper to report the immunohistochemical features of these tumours.14 Limitations of this paper include its small sample size, making it difficult to demonstrate statistically significant results in comparative survival analyses. The retrospective nature of the study also introduces limitations and biases into the data collection process. For the specimens with invasive cancer, all were found to be tubular adenocarcinoma. It has been shown that mucinous carcinoma demonstrates improved survival compared with tubular,6 but this relationship cannot be studied in this series. Compared with other studies, fewer IHC markers were utilized. The IHC markers chosen were those typically performed at our institution. Also, the majority of patients in this series did not undergo a pre-operative serum CA 19-9 test, and, therefore, its utility as a prognostic tool cannot be studied.

Conclusion

IPNB and ICPN are rare precursor lesions that can affect the entire biliary epithelium. At pathology, the majority of patients have invasive carcinoma, thus warranting a radical resection. Prognosis may be superior to traditional cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer. Patients with tumours expressing MUC1 appear to have worse OS and DFSs.

Funding sources

Self-funded.

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

References

- 1.Zen Y, Aishima S, Ajioka Y, Haratake J, Kage M, Kondo F, et al. Proposal of histological criteria for intraepithelial atypical/proliferative biliary epithelial lesions of the bile duct in hepatolithiasis with respect to cholangiocarcinoma: preliminary report based on interobserver agreement. Pathol Int. 2005;55:180–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zen Y, Adsay NV, Bardadin K, Colombari R, Ferrell L, Haga H, et al. Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia: an international interobserver agreement study and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:701–709. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zen Y, Sasaki M, Fujii T, Chen TC, Chen MF, Yeh TS, et al. Different expression patterns of mucin core proteins and cytokeratins during intrahepatic cholangiocarcinogenesis from biliary intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct—an immunohistochemical study of 110 cases of hepatolithiasis. J Hepatol. 2006;44:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohtsuka M, Shimizu H, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Tsuyuguchi T, et al. Intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile duct. Int J Hepatol. 2014;2014:459091. doi: 10.1155/2014/459091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aishima S, Kubo Y, Tanaka Y, Oda Y. Histological features of precancerous and early cancerous lesions of biliary tract carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:448–452. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickenbach K, Galka E, Roggin KK. Molecular mechanisms of cholangiocarcinogenesis: are biliary intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile duct precursors to cholangiocarcinoma? Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2009;18:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanuma Y, Sato Y, Ojima H, Kanai Y, Aishima S, Yamamoto M, et al. Clinicopathological characterization of so-called “cholangiocarcinoma with intraductal papillary growth” with respect to “intraductal papillary neoplasm of bile duct (IPNB)”. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3112–3122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th edn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SC, Lee JK, Jung JH, Lee JS, Lee KH, Lee KT, et al. The clinicopathological features of biliary intraductal papillary neoplasms according to the location of tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:725–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan XS, Xu YY, Qian JY, Yang XB, Wang AQ, He L, et al. Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8595–8604. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton JG, Barrett DA, Maricevich MA, Schnelldorfer T, Wood CM, Smyrk TC, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the biliary tract: a real disease? HPB. 2009;11:684–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minagawa N, Sato N, Mori Y, Tamura T, Higure A, Yamaguchi K. A comparison between intraductal papillary neoplasms of the biliary tract (BT-IPMNs) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (P-IPMNs) reveals distinct clinical manifestations and outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adsay V, Jang KT, Roa JC, Dursun N, Ohike N, Bagci P, et al. Intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasms (ICPN) of the gallbladder (neoplastic polyps, adenomas, and papillary neoplasms that are ≥ 1.0 cm): clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 123 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1279–1301. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318262787c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha FG, Lee H, Katabi N, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, D'Angelica MI, et al. Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct: a biliary equivalent to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas? Hepatology. 2012;56:1352–1360. doi: 10.1002/hep.25786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen TC, Nakanuma Y, Zen Y, Chen MF, Jan YY, Yeh TS, et al. Intraductal papillary neoplasia of the liver associated with hepatolithiasis. Hepatology. 2001;34:651–658. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh KS, Roh HR, Koh YT, Lee KU, Park YH, Kim SW. Clinicopathologic features of the intraductal growth type of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2000;31:12–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takanami K, Yamada T, Tsuda M, Takase K, Ishida K, Nakamura Y, et al. Intraductal papillary mucininous neoplasm of the bile ducts: multimodality assessment with pathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:447–456. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KM, Lee JK, Shin JU, Lee KH, Lee KT, Sung JY, et al. Clinicopathologic features of intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct according to histologic subtype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:118–125. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubota K, Nakanuma Y, Kondo F, Hachiya H, Miyazaki M, Nagino M, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of mucin-producing bile duct tumor and mucinous cystic tumor of the liver: a multi-institutional study by the Japan Biliary Association. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:176–185. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SY, Roh SJ, Kim YN, Kim SZ, Park HS, Jang KY, et al. Expression of MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6 in cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic impact. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:649–657. doi: 10.3892/or_00000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Wang W, Yan L. The clinicopathological features of intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile duct in a Chinese population. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung G, Park KM, Lee SS, Yu E, Hong SM, Kim J. Long-term clinical outcome of the surgically resected intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. J Hepatol. 2012;57:787–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang KT. Intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasm of the gallbladder. Pathology. 2014;46(Suppl 2):S24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paik KY, Heo JS, Choi SH, Choi DW. Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile ducts: the clinical features and surgical outcome of 25 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:508–512. doi: 10.1002/jso.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kloppel G, Adsay V, Konukiewitz B, Kleef J, Schlitter AM, Esposito I. Precancerous lesions of the biliary tree. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, Yamamoto F, Maeda A, Igimi H, Yamamoto M, Yamaguchi R, et al. Tubulopapillary adenoma of the gallbladder accompanied by bile duct tumor thrombus. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8736–8739. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]