The current gold standard technique for correcting cephalic malposition of the lower lateral cartilage is not always effective and, given the prevalence of the malformation in Middle Eastern patients, a new or modified corrective technique has been sought. This study evaluated the efficacy of one such alternative method in 123 primary septorhinoplasty operations and describes its advantages.

Keywords: Cephalic malposition of lower lateral cartilage, Repositioned lateral crural flap, Septorhinoplasty

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Cephalic malposition of the lower lateral cartilage (CMLLC) is a relatively common anatomical variant, particularly in Middle Eastern patients. The characteristics of CMLLC include long alar creases, a boxy and ball-shaped nasal tip, parenthesis tip deformity and external valvular incompetence. The gold standard for correcting CMLLC is the lateral crural strut graft (Gunter graft), but many patients experience problems after this technique.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the efficacy of the repositioned lateral crural flap (RLCF) technique in correcting CMLLC, and to discuss the cosmetic and functional results.

METHODS:

In the present study, 123 primary septorhinoplasty operations using the RLCF technique were performed between May 2012 and March 2013. The mean follow-up period was 11.4 months (range nine to 24 months). Four parameters were measured and compared pre- and postoperatively: the angle between the line connecting the maximum convexity of the lower lateral cartilage (LLC) to the tip-defining point and midline on each side (angle of rotation); the total distance between the maximum convexity of LLC right and left to midline (representing the size of the parenthesis deformity); satisfaction scale rating of the patients’ nasal tip appearance; and the satisfaction scale rating of patients’ breathing through their nostrils.

RESULTS:

The mean angle of the LLC to the midline significantly increased and the mean distance between the maximum convexities was significantly reduced, indicating correction of the malposition and reduction of the parenthesis deformity, respectively. The mean satisfactory scale ratings of nasal tip appearance and breathing quality were also significantly improved.

CONCLUSION:

CMLLC can be corrected using the RLCF technique, resulting in both aesthetic and functional improvements.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La déviation céphalique des cartilages alaires (DCCA) est une variante anatomique relativement courante, particulièrement chez les patients moyen-orientaux. Ses caractéristiques sont de longs plis alaires, une pointe nasale carrée et bulbeuse, un aspect en parenthèse de la pointe et une incompétence valvulaire externe. La greffe de l’étai des crus latérales (greffe de Gunter) est la norme pour corriger la DCCA, mais de nombreux patients éprouvent des problèmes par la suite.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer l’efficacité de la transposition des crus latérales (TCL) pour corriger la DCCA et en présenter les résultats esthétiques et fonctionnels.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Dans la présente étude, les chirurgiens ont effectué 123 opérations de septorhinoplastie primaire entre mai 2012 et mars 2013 par TCL. Ils ont assuré un suivi moyen de 11,4 mois (plage de neuf à 24 mois). Ils ont mesuré et comparé quatre paramètres avant et après l’opération : l’angle entre la ligne reliant la convexité maximale des cartilages alaires (CA) à la projection de la pointe et la portion médiane de part et d’autre (angle de rotation), la distance totale entre la convexité maximale du CA de part et d’autre de la portion médiane (correspondant à la mesure de l’aspect en parenthèse de la pointe), l’échelle de satisfaction des patients à l’égard de l’apparence de leur pointe nasale et l’échelle de satisfaction à l’égard de leur respiration nasale.

RÉSULTATS :

L’angle moyen entre les CA et le plan médian augmentait considérablement et la distance moyenne entre les convexités maximales diminuait de manière significative, confirmant respectivement que la déviation était corrigée et que l’aspect en parenthèse était réduit. L’échelle de satisfaction révélait également des évaluations moyennes beaucoup plus positives de l’apparence de la pointe nasale et de la qualité respiratoire.

CONCLUSION :

Il est possible de corriger la DCCA par TCL et d’ainsi obtenir des améliorations à la fois esthétiques et fonctionnelles.

Cephalic malposition of the lower lateral alar cartilage is a relatively common anatomical variant, particularly in Middle Eastern patients (1); it was first described by Sheen (2) in 2000. The diagnosis of cephalic malposition of the lower lateral alar cartilage is now widely accepted; however, to date, a definitive classification has not been established. It has been described as the lateral crura positioned ≤30° from midline directed toward the ipsilateral medial eye canthus. A normally positioned (orthotopic) lateral crura diverges ≥45° from midline and is directed toward the ipsilateral lateral eye canthus (3). According to previous studies on alar cartilage malposition (4–6), cephalically positioned alar cartilages show a variety of characteristics including long alar creases, boxy (7) and ball-shaped nasal tip (8), parenthesis tip deformity and, finally, external valvular incompetence (9–11). Previous studies have suggested techniques to correct cephalic malposition (12–15), but the gold standard is still lateral crural strut graft (Gunter graft) (16); however, many patients experience problems after this technique. In the present study, the efficacy of the repositioned lateral crural flap in correcting cephalic malposition of lateral crura was evaluated, and the cosmetic and functional results are discussed and compared with previous studies.

METHODS

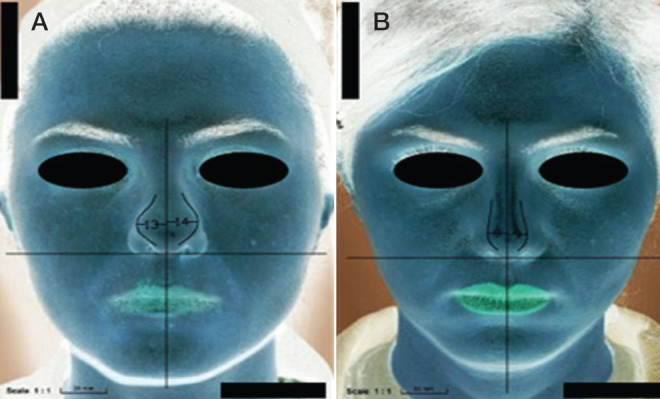

Between May 2012 and March 2013, a total of 123 primary septorhinoplasty operations were performed to correct cephalic malposition of the lower lateral alar cartilage. Patients were >18 years of age (110 women and 13 men). They were selected based on their preoperative standard photographs (scale of 1:1 and in inverted colour so that the parenthesis deformity could be better visualized and diagnosed) (Figure 1) and preoperative examination by the senior author; the diagnosis was confirmed intraoperatively, as explained in the next section. Exclusion criteria were history of previous septorhinoplasty; severe external valve incompetence (complete alar side collapse observed during deep inspiration); and alar pinching without parenthesis deformity The process was explained to all patients, who then signed an informed consent supplied by the ethics committee. The present study was approved by the regional hospital ethics committee and IUMS Medical Ethics committee.

Figure 1).

Standard and inverted-colour photography. Deformity could be better visualized and diagnosed on the inverted-colour picture

All patients underwent open reconstructive surgery by the senior author. After dissection of the skin and exposure of the lower lateral cartilage, maximum bulging on the cartilage was marked and a line connecting the maximum bulge and the tip-defining point was drawn with surgical marker (Figure 2). All patients had convexity and maximum bulging on their lower lateral cartilage.

Figure 2).

The shape of the parenthesis deformity seen intraoperatively. Area of maximum bulging (black arrow), tip-defining point (white arrow) and the connecting line are demonstrated

The angle between this line and the midline was measured using a protractor (Figure 3); this angle is more accurate and easier to measure using a protractor. The smaller the angle, the greater the malposition; in all cases, this angle was <45°; thus, the malposition was confirmed intraoperatively.

Figure 3).

Measurement of the angle between the line connecting the the maximum bulge and the tip-defining point, and midline

After removal of the hump and other procedures such as septoplasty, spreader graft, etc, the tip plasty was begun. An incision was made on the cartilage on the area of maximum convexity and, following the dissection of skin and mucosa, the distal part was separated, overlaid and sutured onto it to reposition the cartilage in a more caudal position (Figures 4 and 5). The angle between the previously marked line and the midline was remeasured and the difference of these two angles – the angle of lower lateral rotation – was selected as a parameter. The projection and rotation of tip could be changed based on these measurements. Columellar strut and interdomal sutures were used in all cases.

Figure 4).

The cutting of maximum bulging with a number 11 scalpel and the separating of cartilage from mucosa and skin

Figure 5).

The caudal segment of cartilage is repositioned; the cartilage is separated from the mucosa and skin caudally, then overlaid and sutured

All patients were followed up for a mean of 11.4 months (range nine to 24 months) postoperatively; at that time, a second photograph was obtained. These photographs were colour inverted and, using AutoCAD (Autodesk, USA), the curves of lateral crura were drawn separately on each side. The maximum convexity point was located on each curve and a perpendicular line was drawn to meet the midline. The distance to midline on each side was measured and added up; this parameter was then compared with that from the preoperation photographs (Figure 6). The patients were provided with a visual analogue scale (VAS; scored from 0 to 10, in which 0 is the worst and 10 is the best possible outcome) before and after the surgery, on which they rated their breathing quality through their nose and their satisfaction with the appearance of their nasal tip (Figure 7). The pre- and postoperative scores were compared.

Figure 6).

The distance between maximum bulging on either side on inverted colour photography preoperatively (A) and postoperatively (B)

Figure 7).

Visual analogue scale. This questionnaire was given to patients before and after surgery

For statistical analysis, paired sample t tests were performed on each pair. The P value for each comparison was calculated using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corporation, USA); P<0.05 was considered to be statiscally significant for all four comparisons.

RESULTS

Of 123 patients, complete data were available for 104 and standard postoperative photography and follow-up were available for 99. The four parameters were compared:

The angle between the line connecting maximum convexity to the tip-defining point and midline on each side: preoperatively, the mean angle was 36.95±4.25° and 36.46±4.31° on the right and left side, respectively; these increased to 56.37±7.14° and 56.23±7.24°, respectively, after the procedure (P<0.05, Table 1).The mean angle of rotation was 19.42±6.77°. These changes reduced cephalic malposition significantly.

The total distance between the maximum convexity of right and left side to the midline (measured on the inverted colour photographs): preoperatively, mean distance was 23.11±2.13 mm; postoperatively, mean distance was 15.14±2.21 mm (P<0.05, Table 1). Parenthesis deformity was, therefore, relatively corrected.

Mean patient-rated VAS scores for satisfaction with nasal tip appearance were 4.37±1.89 preoperatively, compared with 8.19±1.36 postoperatively (P<0.05, Table 2, Figures 8, 9 and 10).

Mean patient-rated VAS scores for satisfaction with quality of breathing through their nostrils were 7.80±2.35 preoperatively compared with 8.84±1.36 postoperatively (P<0.05, Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Angle and convexity of lower lateral cartilage before and after surgery

| n | Mean ± SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angle before procedure during surgery on right side, ° | 104 | 36.9510±4.25284 | <0.05 |

| Angle after procedure during surgery on right side, ° | 104 | 56.3775±7.14608 | |

| Angle before procedure during surgery on left side, ° | 104 | 36.4615±4.31507 | <0.05 |

| Angle after procedure during surgery on left side, ° | 104 | 56.2356±7.24232 | |

| Total distance between the maximum convexity of the left and right on negative photographs before surgery, mm | 99 | 23.1196±2.13728 | <0.05 |

| Total distance between the maximum convexity of the left and right on negative photographs after surgery, mm | 99 | 15.1413±2.21176 | <0.05 |

| Right tip-defining point variation | 92 | 7.9783±2.70 | |

| Left tip-defining point variation | 104 | 19.77±6.95 | |

| Angle of rotation, ° | 102 | 19.42±6.77 |

TABLE 2.

Patient-reported visual analogue scale scores* of nasal appearance and breathing satisfaction before and after surgery

| Satisfaction | n | Mean ± SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance before surgery | 99 | 4.3737±1.89298 | <0.05 |

| Appearance after surgery | 99 | 8.1919±1.36783 | |

| Breathing before surgery | 99 | 7.8081±2.35032 | <0.05 |

| Breathing after surgery | 99 | 8.8485±1.36549 |

On a scale of 0 to 10, in which 0 is the worst possible outcome and 10 is the best possible outcome

Figures 8, 9 and 10).

Standard profile and lateral view photography before and approximately 13 to 24 months after surgery. All surgeries were performed using the repositioned lateral crural flap technique

DISCUSSION

Considering the high prevalence of cephalic malposition and the need for correction, we investigated a relatively new technique, namely, the repositioned lateral crural flap. Previously used techniques for the correction of cephalic malposition of the lower lateral alar cartilage, such as the lateral crural strut graft (Gunter graft), which has been successful, and now is the gold standard procedure to correct the cephalically positioned crura, are not always effective. In some cases, there is insufficient graft material available in the nasoseptal cartilage and, therefore, grafts from other places (eg, ear cartilage) are required. Furthermore, in some patients, the grafts are visible or palpable after the surgery, which gives patients an unpleasant foreign body sensation. To prevent this, two types of cartilage supports have been developed. Some authors have resected the malpositioned lateral crus and replaced it as a free graft in a more caudal position (2,17). Others have used an extra cartilage graft, placed caudally below the malpositioned lateral crus in the alar rim (1); however, when a rigid cartilage graft is placed along the interior of the alar rim, the ala may not adapt to the nasal muscles (15). Our technique does not impede fine movements of the posterior alar rim because the transposed cartilage segment supports only the anterior part of the alar rim, as in normal anatomy.

In our technique, the lateral crus was obliquely divided at the point of maximum convexity with different distances from the dome (ie, the site of cutting the cartilage was not same in all cases and the length of the cut from the dome was different in every case) and the two segments were prepared. The anterior segment was transposed caudally for a normal anatomical position and fixed to the posterior segment in a more caudal position. This technique does not require an extra cartilage graft material, which may be limited in some septorhinoplasty operations that use cartilage grafts such as spreader graft, batten graft, columellar strut graft, tip graft and cap graft. Also, transection of the lateral crus can be used to control the projection and also rotation of the nasal tip.

Our method appears to be less problematic and potentially successful when performed in patients with lower grades of cephalically positioned crura and moderate external valve incompetence. To address the lack of a definitive classification for cephalic malposition, we suggest the following:

Type 1. Patients with parenthesis deformity (ball or boxy tip) without alar retraction (Figure 11).

Type 2. Patients with boxy or ball tip showing alar retraction and more columella show (Figure 12).

Type 3. Patients with cephalic malposition without ball or boxy tip but showing pinching in external valve (Figure 13).

Figure 11).

Parenthesis deformity (boxy tip) without alar retraction

Figure 12).

Ball tip showing alar retraction and more columella show

Figure 13).

Cephalic malposition without boxy tip but showing pinching in external valve.

Classic parenthesis deformity includes only types 1 and 2. All patients in the present study had type 1 or 2 deformity. Type 3 deformity is not a parenthesis deformity but, with some modification, this technique can be used for all three types of cephalic malposition. For example, for type 1, the caudal segment of the distal cartilage flap must be resected and, in type 3, creation of a flap and overlapping is sufficient; it does not require more caudal repositioning. The present data represent the efficacy of this technique in correcting the convexity of lower lateral alar cartilage and external valve collapse. One significant result in the present study is that for patients showing distinct cephalic mal-position, alar retraction and external valve incompetence, a more distal rotation in repositioning the lower lateral cartilage not only leads to correction of cephalized crura but also corrects alar retraction without any need to place rim grafts (Figure 14).

Figure 14).

Alar retraction and columellar show and intraoperative correction with repositioned lateral crural flap technique without any rim graft

In Oktem et al (15), cartilage Z plasty was performed on the lateral crus of the alar cartilage to treat malposition; they concluded that alar cartilage malposition was successfully corrected in patients with aesthetic and functional improvements (15). However, our study has two significant differences from the Oktem et al study. First, the point of cartilage division was not consistent because it was based on the maximum convexity of lateral crus and, second, we used angle of lower lateral cartilage rotation and distance to midline as two quantitative factors to analyze the statistical significance of this technique. Boccieri and Raimondi (18) divided the lateral crus as anterior and posterior segments with stair-step incision. They repositioned the anterior segment over the posterior segment to correct the parenthesis deformity due to alar cartilage malposition. In addition, when there were lateral crura with an over-projection and ptosis of the tip, they combined reposition of anterior segment with a sliding backward movement on the posterior segment to attain the desired degree of rotation and projection as a lateral crural steal technique. They obtained good results in 22 patients (18). Tellioglu and Cimen (19) folded the cephalic part of the lateral crus to reinforce it. Turn-in folding of the cephalic portion of the lateral crus was performed to treat a concave alar rim deformity, to prevent weakness of the alar rim and also to correct a collapsed alar valve. Unfortunately, this technique cannot correct malpositions such as abnormal lateral crural axes. Gruber et al (20) reported the intercartilaginous graft technique, which is a modification of the lateral crural strut graft. In this report, one important caveat was noted that the cephalic end of the lateral crus should not be excised in the presence of alar retraction or potential alar retraction (20).

The cephalically rotated lateral crura leave the alar rims without cartilaginous support, which causes destabilization of normal airway competence. Malposition of the lateral crura not only causes functional problems, but also leads to aesthetic problems such as broad and bulbous nasal tip with parenthesis deformity. In addition, when there is a mal-position of the lateral crura, conventional cephalic excision of the lateral crura can exaggerate both functional and aesthetic problems (15).

Limitations

One limitation of the present study was the accuracy of the protractor used to measure intraoperative angles (previously defined). The lack of a grading score for cephalic malposition was another. The interference of other techniques, such as interdomal suture (21), on the angle of rotation of lower lateral cartilage was another consideration. Patient VAS scores may also be subjective; for instance, the appearance of parts of nose other than the tip may lead to misjudgment and, therefore, a lower appearance score is given by patients. For functional scoring, objective measurements (such as rhinomanometery) may be better for evaluation of breathing function. Finally, we did not have control group; for future studies, it is suggested a control group be used.

CONCLUSION

Cephalic malposition of the lower lateral cartilage can, in many patients, be aesthetically and functionally corrected using repositioned lateral crural flaps. Advantages of this technique include the following: extra graft material is not required; the lateral crural complex is augmented; no disruption to alar muscle movement; and the projection and rotation of the nasal tip can be adjusted.

This method could also be used for patients undergoing revision rhinoplasty and for those in whom there is less available graft material; however, the present study was performed on primary rhinoplasty.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A. Rhinoplasty for Middle Eastern noses. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1343–54. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817741b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheen JH. Rhinoplasty: Personal evolution and milestones. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1820–52. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200004050-00033. discussion 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Constantian MB. Functional effects of alar cartilage malposition. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;30:487–99. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamra ST. Repositioning the lateral alar crus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1244–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh CC, Williams EF., III Cosmetic and functional effects of cephalic malposition of the lower lateral cartilages: A facial plastic surgical case study. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42:539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janis JE, Trussler A, Ghavami A, Marin V, Rohrich RJ, Gunter JP. Lower lateral crural turnover flap in open rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1830–41. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a65ba2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohrich RJ, Adams WP. The boxy nasal tip: Classification and management based on alar cartilage suturing techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1849–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinney P. Management of the bulbous nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:906–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:38–54. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199607000-00007. discussion 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constantian MB. The incompetent external nasal valve: Pathophysiology and treatment in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:919–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M, Zwiebel S, Guyuron B. Frequency of the preoperative flaws and commonly required maneuvers to correct them: A guide to reducing the revision rhinoplasty rate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:769–76. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a01457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boahene KD, Hilger PA. Alar rim grafting in rhinoplasty: Indications, technique, and outcomes. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11:285–9. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuran I, Sadikoglu B, Turan T, Hacikerim S, Bas L. The sandwich technique for closure of a palatal fistula. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:434–7. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200045040-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adham MN, Teimourian B. Treatment of alar cartilage malposition using the cartilage disc graft technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1118–25. discussion 26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oktem F, Tellioglu AT, Menevse GT. Cartilage Z plasty on lateral crus for treatment of alar cartilage malposition. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:801–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunter JP, Friedman RM. Lateral crural strut graft: Technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:943–52. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Constantian MB. The two essential elements for planning tip surgery in primary and secondary rhinoplasty: Observations based on review of 100 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1571–81. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000138755.00167.f5. discussion 82–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boccieri A, Raimondi G. The lateral crural stairstep technique: A modification of the kridel lateral crural overlay technique. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008;10:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2007.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tellioglu AT, Cimen K. Turn-in folding of the cephalic portion of the lateral crus to support the alar rim in rhinoplasty. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2007;31:306–10. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruber RP, Kryger G, Chang D. The intercartilaginous graft for actual and potential alar retraction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:288e–96e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31816c3b9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty: A simplified, three-stitch, open tip suture technique. Part I: Primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1491–502. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199904050-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]