Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Governmental agencies (US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency) implemented initiatives to improve pediatric clinical research, starting in 1997 and 2007, respectively. The aim of this review was to quantify the unlicensed and off-label drug uses in children before and after these implementations.

METHODS: Literature review of unlicensed and off-label drug uses was performed on PubMed and Google-Scholar from 1985 to 2014. Relevant titles/abstracts were reviewed, and articles were included if evaluating unlicensed/off-label drug uses, with a clear description of health care setting and studied population. Included articles were divided into 3 groups: studies conducted in United States (before/after 2007), in Europe (before/after 2007), and in other countries.

RESULTS: Of the 48 articles reviewed, 27 were included. Before implementation of pediatric initiatives, global unlicensed drug use rate in Europe was found to be 0.2% to 36% for inpatients and 0.3% to 16.6% for outpatients. After implementation, it marginally decreased to 11.4% and 1.26% to 6.7%, respectively. Concerning off-label drug use rates, it was found to be 18% to 66% for inpatients and 10.5% to 37.5% for outpatients before the implementation. After implementation, it decreased marginally to 33.2% to 46.5% and to 3.3% to 13.5%, respectively. In other countries, unlicensed and off-label drug use rates were found to be, respectively, 8% to 27.3% and 11% to 47%.

CONCLUSIONS: Governmental initiatives to improve clinical research conducted in children seem to have had a marginal effect to decrease the unlicensed and off-label drug uses prevalence in Europe.

INDEX TERMS: off-label use, pediatrics, review

INTRODUCTION

Before a drug can be approved for sale in a given market, governmental authorities in each country have to assess its safety, efficacy, and quality. At the end of this process, pharmaceutical companies are granted market authorization, and the drug gets a license for marketing in the country (e.g., Notice of Compliance in Canada). The drug also has a label (i.e. drug monograph), specifying the details for drug use (e.g., target population, dose, indication, specific use).

Virtually all drugs that get an approval for use in adults should also get an approval for use in children; this is often not the case considering the paucity of clinical research for that population. Therefore, drug monographs are frequently silent about the use of the drug in children. However, in most legislation, clinicians can prescribe to children a drug approved for adult (i.e., an off-label use). In some case, clinicians must also import from another country a drug that has not obtained a license for marketing (i.e., an unlicensed use). Both situations expose clinicians and patients to delays, costs, and risks. In response to these challenges, governmental authorities have established various strategies and regulations to oversee and promote clinical research in children and hopefully to decrease both unlicensed and off-label drug uses.

In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) adopted the FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA),1 followed in 2002 by the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA),2 which provided an incentive for drug companies to conduct FDA-requested pediatric studies. In 2003, the FDA also created the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), which requires drug companies to study their products in children under certain circumstances.3 In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) created the European (EU) Pediatric Regulation, in 2007.4 Its objective was to improve the health of children in Europe by facilitating the development and availability of medicines for that population. In other countries, such as in Canada, the Pediatric Expert Advisory Committee was created in 2009 to provide advice to Health-Canada in the development, licensing, and post-approval monitoring of drugs.5

Our hypothesis was that even though these initiatives were not implemented to decrease unlicensed or off-label drug use rates, they probably would have a favorable consequence on those uses. Ten years after the first regulations, we could expect that the prevalence of unlicensed and off-label prescriptions in children would have decreased. Thus, we reviewed the literature to explore the effect of the regulatory changes.

The primary objective of this literature review was to determine the effect of governmental initiatives to improve clinical research in children on unlicensed and off-label drug uses in inpatient and outpatient settings in the world. The secondary objective was to determine the unlicensed and off-label drug use rates in countries where no governmental initiatives to improve clinical research in children have been implemented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

First, a review of published studies on unlicensed and off-label drug use in children in any health care setting was performed by our research team using the PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) and Google Scholar (Google, Mountain View, CA) databases and related links to articles published from 1985 to July 2014. Medical subject headings and free text searches used the following terms “off-label use,” “unlicensed use,” “drug labeling,” “drug use review,” “child,” and “pediatrics.” References in reviewed articles were also screened, and additional studies were included, if relevant. Identified article titles and abstracts were scanned for relevance. Studies evaluating unlicensed or off-label drug use, with a clear description of the health care setting, the studied population, and numerical details to validate the drug use rate were included. Studies when only abstract could be retrieved were excluded as well as updates, literature reviews, and studies that had results concerning specific drug classes. Reasons for exclusion were documented. Unlicensed drug use was defined as the use of a non-marketed drug. Off-label drug use was defined as the use of a drug in an unapproved way.

Study Variables

Year of publication, year of data collection, country where the study was performed, type of study, duration of the study, number and type of patients included, number of prescriptions included, prevalence and definition of unlicensed and off-label drug uses, scientific support for off-label drug use, and patient or parent's consent information were collected.

Data Analysis

We divided studies into 3 groups: studies conducted in the United States, studies conducted in Europe, and studies conducted in other countries. For the first 2 groups, we divided studies into 2 subgroups: before and after governmental initiatives. In the United States, the cutoff date for the governmental initiative was set as 2007. The PREA was enacted in 2003 and considering the lag time, we considered this date reasonable. In Europe, the cutoff date for governmental initiative was set as 2007, when the EU Pediatric Regulation came into force. No cutoff date was selected for the other countries.

We summarized the key results of studies about unlicensed and off-label drugs use in children before and after governmental initiatives for Europe, and key results of studies for unlicensed and off-label drug uses in pediatrics for other countries, where no pediatric regulations were enacted. Descriptive statistics were performed.

RESULTS

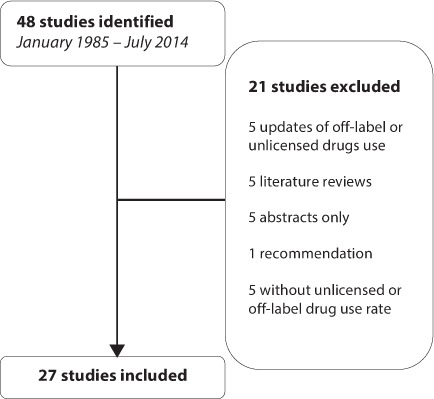

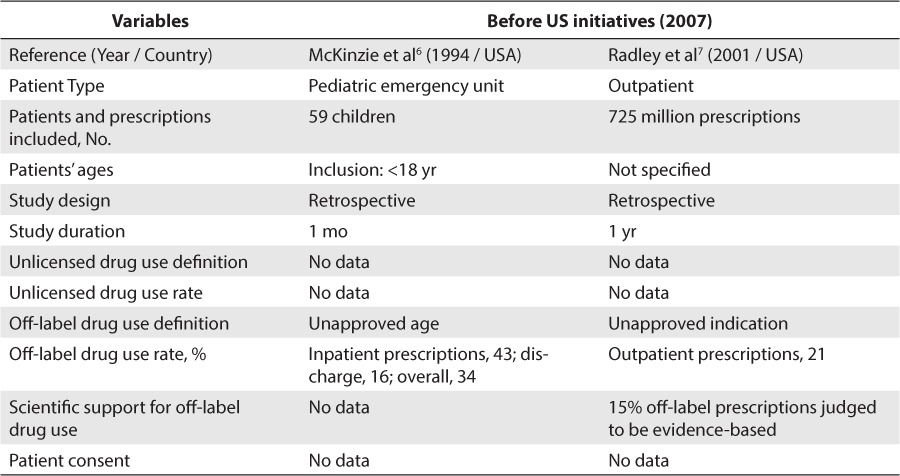

From 1985 to July 2014, a total of 48 studies evaluating unlicensed and off-label drug use in children were reviewed. Of these studies, 27 articles were included in our review. The reasons of exclusion of 21 articles are detailed in Figure. Concerning studies conducted in the United States, 2 studies were included (Table 1).6,7 Both studies were conducted before the set cutoff date, respectively, in 1994 and 2001. No information on unlicensed drug use rate was retrieved in these studies. One study was conducted by McKinzie et al6 found a 34% off-label drug use rate in inpatients, whereas the study conducted by Radley et al7 found a 21% off-label drug use rate in outpatients. However, considering that only 2 studies could be included and that both studies were conducted before the set cutoff date, we could not conclude anything about the impact of US initiatives on unlicensed and off-label drug use rates.

Figure.

Flow of the identified studies

Table 1.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate In the United States, Before and After the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (1997)

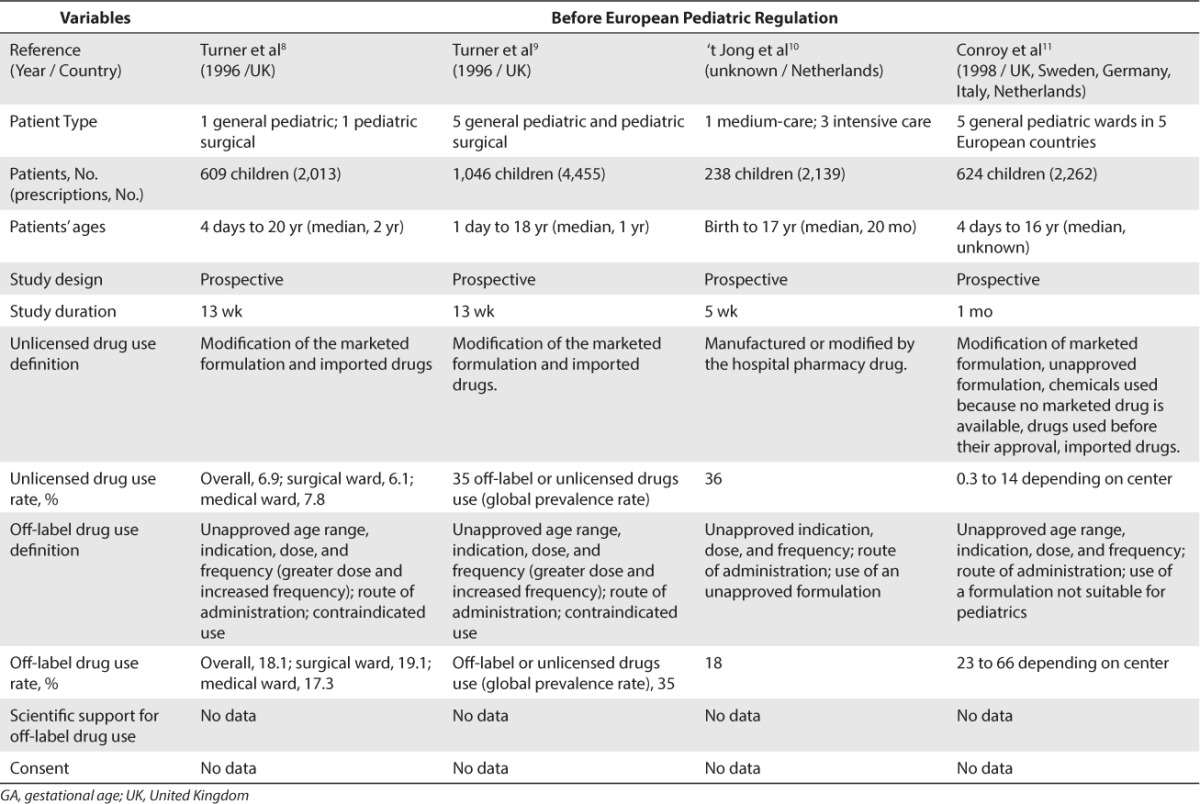

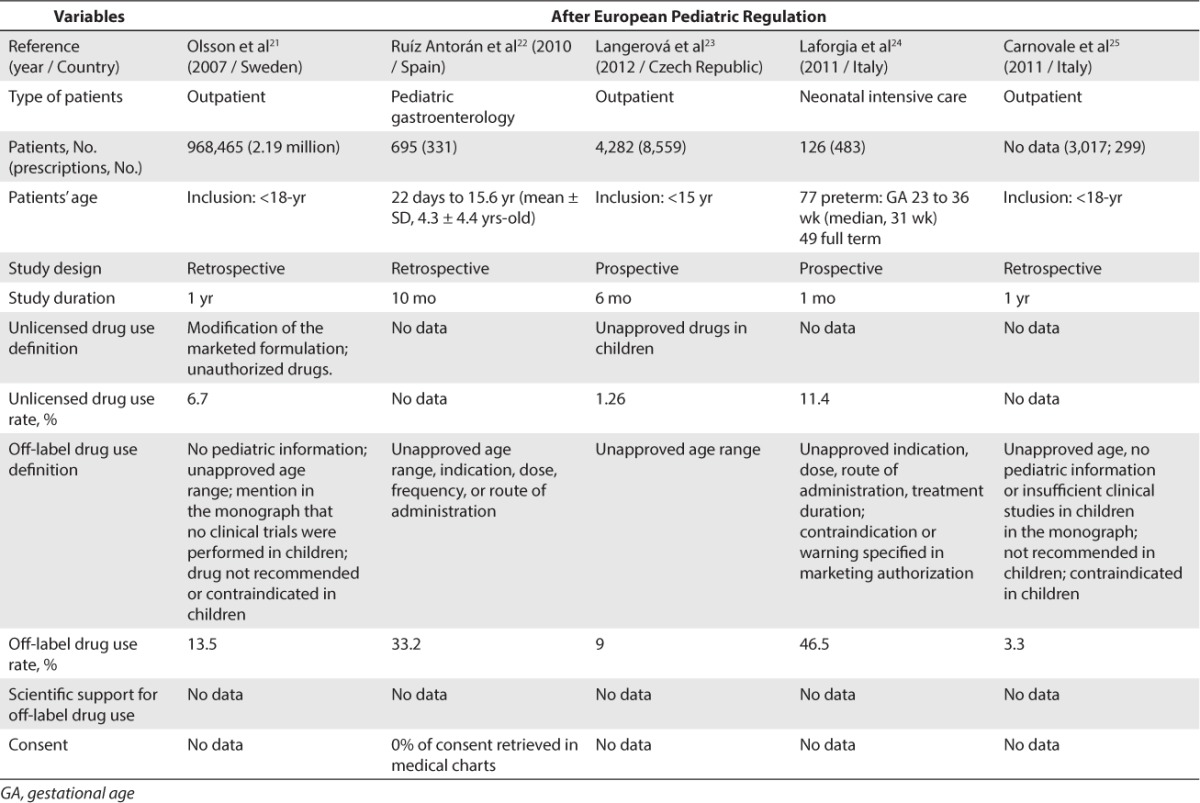

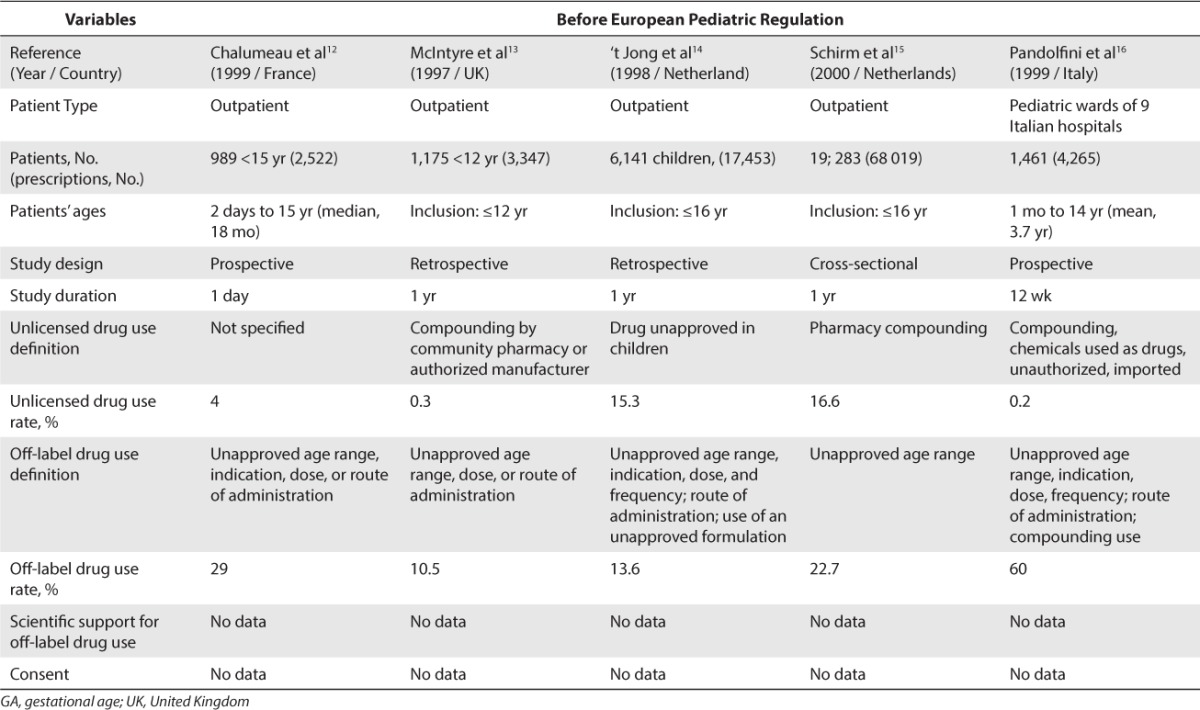

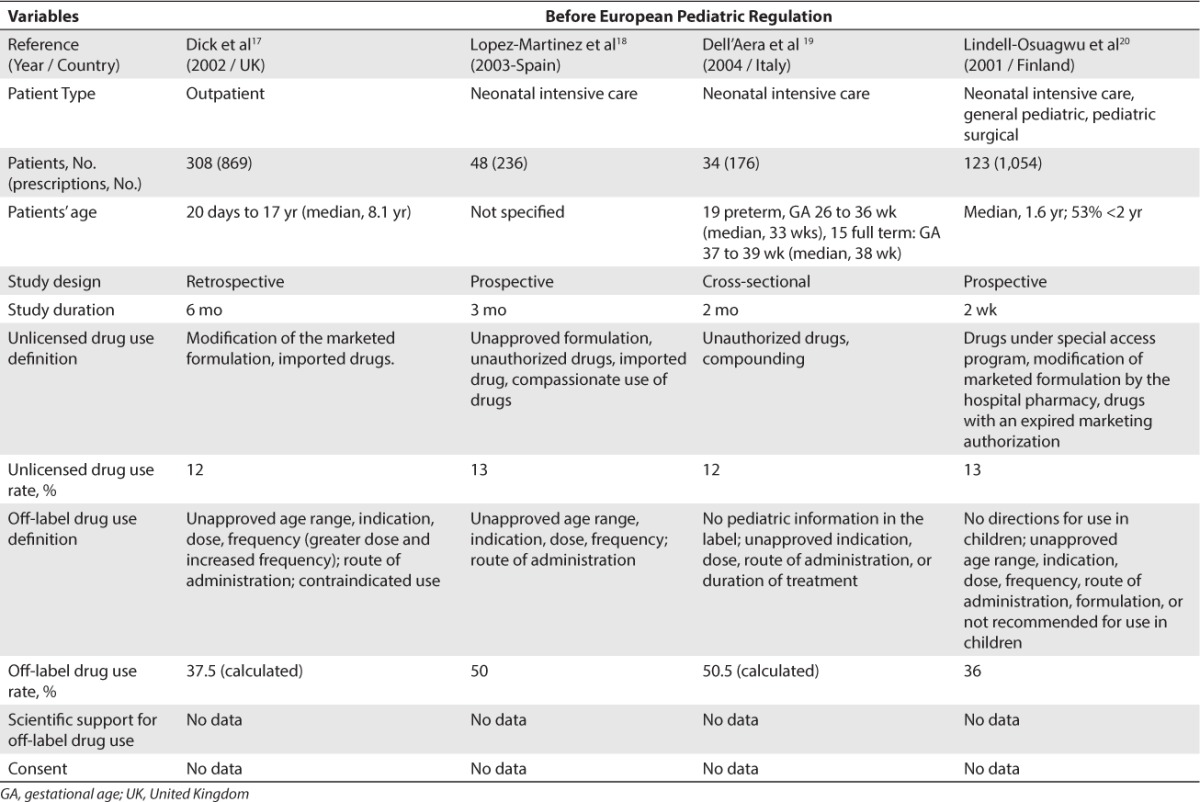

Concerning Europe, 18 studies were included.8–25 A total of 13 studies were conducted before the EU Pediatric Regulation came into force in 2007 (Table 2)8–20 and 5 studies were conducted after this regulation was implemented (Table 3).21–25 Before the implementation of the EU Pediatric Regulation, unlicensed drug use rate was found to be between 0.2% and 36% for inpatients and between 0.3% and 16.6% for outpatients. Off-label drug use rate was found to be between 18% and 66% for inpatients and between 10.5% and 37.5% for outpatients. After the EU Pediatric Regulation came into force in 2007, unlicensed drug use rate was found to be at 11.4% for inpatients and between 1.26% and 6.7% for outpatients. Off-label drug use rate was found to be between 33.2% and 46.5% in inpatients and between 3.3% and 13.5% in outpatients.

Table 2.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate in Europe Before the European Pediatric Regulation (2006)

Table 3.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate in Europe After the European Pediatric Regulation (2006)

Table 2.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate in Europe Before the European Pediatric Regulation (2006) (cont.)

Table 2.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate in Europe Before the European Pediatric Regulation (2006) (cont.)

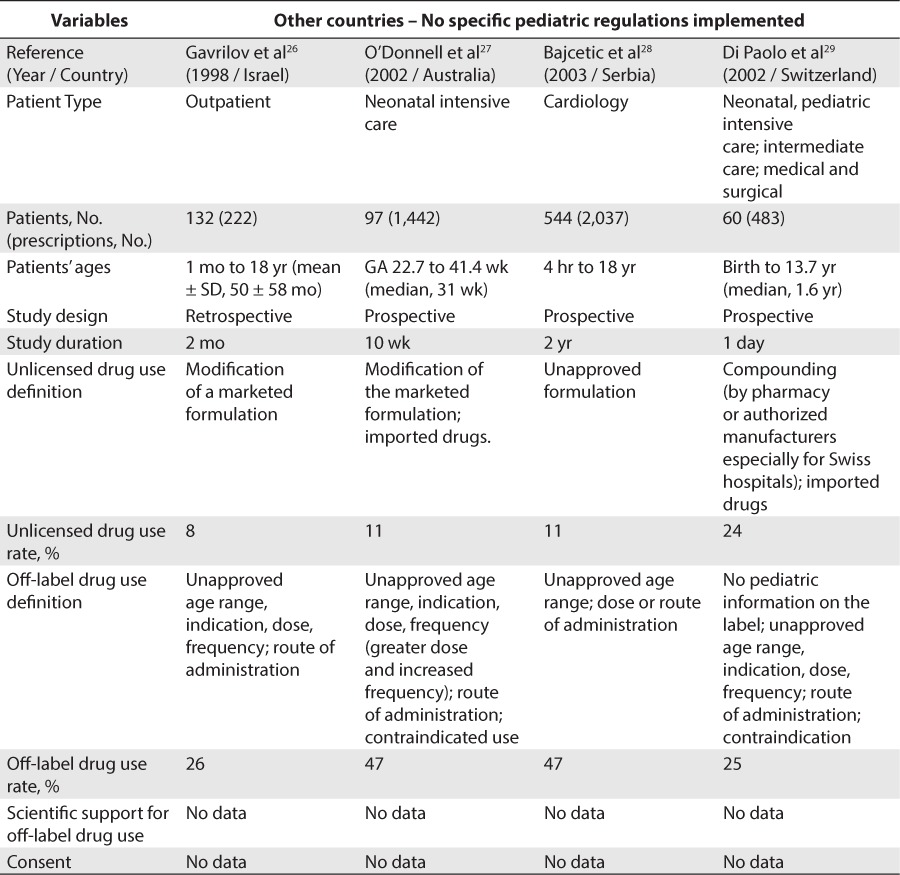

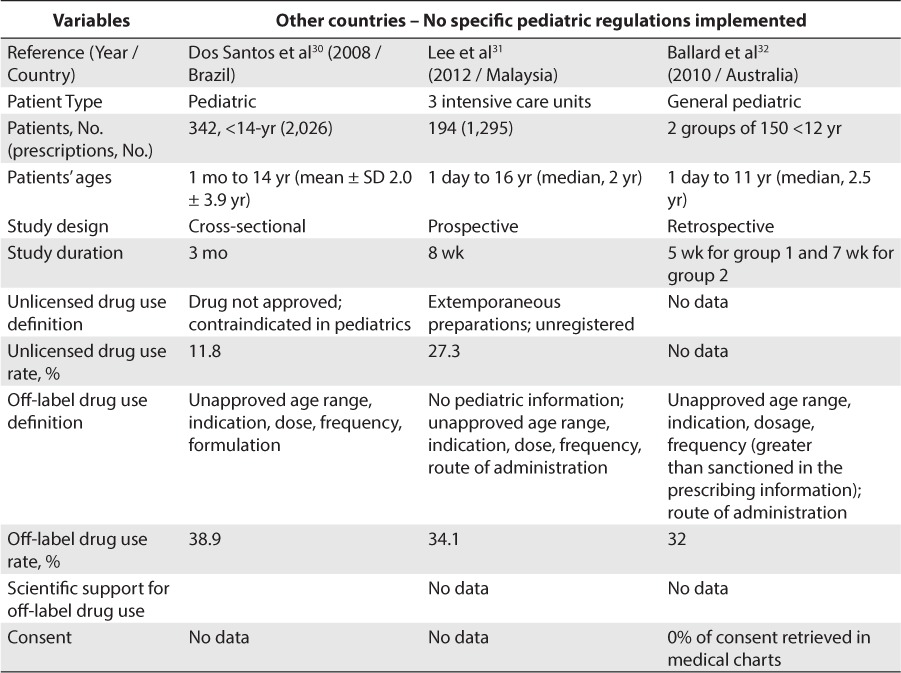

Concerning studies conducted in countries other than the United States and Europe, 7 studies were included (Table 4).26–32 Unlicensed drug use rate was found to be between 11% and 27.3% for inpatients and 8% for outpatients. Off-label drug use was found to be between 25% and 47% for inpatients and 26% for outpatients.

Table 4.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate In Other Countries With No Pediatric Regulation

Table 4.

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Use Rate In Other Countries With No Pediatric Regulation (cont.)

Concerning the scientific support for off-label drug use, only 1 included study reported a rate of off-label drug use associated with strong scientific support. Radley et al7 reported that 15% of off-label drug use was associated with strong scientific support.

DISCUSSION

Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Uses Rates

This literature review provides an overview of the main published studies concerning the unlicensed and off-label drug uses in children in the past 3 decades. These results suggest that the governmental initiatives and regulations implemented in Europe to encourage drug research in children have had a marginal impact on unlicensed and off-label drug use rates on inpatient and outpatient health care settings. In Europe, the reported range of unlicensed drug use rates decreased from 0.2% to 36% to a single 11.4% value for inpatients and from 0.3% to 16.6% to 1.26% to 6.27% for outpatients. Regarding off-label drug use rates, the reported range went down from 18% to 66% to 33.2% to 46.5% for inpatients and from 10.5% to 37.5% to 3.3% to 13.5% for outpatients.

However, because these incentives were implemented to enhance pediatric clinical research, it would be interesting to know how many drugs have been studied in children by authorities since those regulations were enacted. Unlicensed and off-label drug uses are not limited to pediatrics. However, it is often more prevalent in children, especially in neonates. In this literature review, unlicensed drug use rates in neonatal intensive care units were found to be between 11.4% and 12%, and off-label drug use rates were between 46.5% and 50.5%.19,24

These results highlight the great disparities in unlicensed and off-label drug uses between studies, with large ranges of unlicensed and off-label drug use rates. Many explanations might be given for these disparities. Unlicensed and off-label drug use definitions are different among studies, which interferes with these unapproved drug use rates. Also, definitions can be different depending on the studies: unlicensed and off-label drug uses can be based on the number of unapproved prescriptions, the number of patients requiring an unapproved drug use, etc. Additionally, study context is different for each study, which can interfere with the results: different countries, different marketed drugs, different formulations available, different populations, and different information contained in drug monographs. Regarding off-label drug uses, the design of the study can also be a factor of disparity: retrospective studies can be a barrier to obtaining all information about indications for use, for example. Many factors may explain why both unlicensed and off-label drug use rate are still quite high in various countries and their regulations.

Explanations for Unlicensed Drug Uses

The use of unlicensed drugs in a given country can be motivated by different factors. Such use usually relies on an individual request by a physician addressed to the regulatory authority to import a specific drug marketed in another country for a specific patient. The regulatory process usually allows drug importation when currently available drug alternatives have been used without success, and the patient's condition remains critical. Such a process is usually complex, lengthy, and costly. Clinicians may want to import an unlicensed drug into a given country because the drug manufacturer has not applied for a notice of compliance in the current market (e.g., no local market interest), because the regulatory authority is actually treating the request (e.g., administrative delays), because the drug manufacturer cannot satisfy the regulatory requirements (e.g., incomplete drug submission), or because the patients/parents have identified a potential drug therapy on the Internet. In pediatrics, such drug importation may also be motivated by the availability of a pediatric formulation in another country and drug shortages.

Explanations for Off-Label Drug Uses

The use of an off-label drug in a given country can also be motivated by different factors. Governmental initiatives and regulations to increase drug research in children have put more emphasis on the development and marketing of new drugs. Therefore, off-label drug use rates may stay the same for a while because the use of many old drugs, which have current, active generic manufacturers, will not have any clinical research in children conducted (e.g. morphine being indicated only for children 12-years and older) to update their drug monographs and add, for instance, other age groups in their regulatory documentation. Health care decision makers and clinicians are also used to prescribing, dispensing, and monitoring drugs in children, using the currently available drug information in the literature, rather than the expected information contained in the drug monograph. This may have contributed to sending the wrong signal to the drug industry, saying the drug will be used and even reimbursed in children, no matter what is included in the drug monograph. To our knowledge, there are no published studies that compare the use and the reimbursement of similar drugs with or without pediatric information in their drug monograph. The question of whether third-party payers, pharmacology and therapeutics committees, physicians, pharmacists, and other stakeholders favor drugs with approved indications and information for children versus other drugs in their current pediatric practice should be addressed. Therefore, all stakeholders should think about their decision-making processes so a coherent signal is sent to the drug industry.

Many other factors should be mentioned to explain the current high-rate of off-label drug use in children. It is more complex to conduct research in pediatrics considering the balance between the advantages and the risks, the consent issues depending on the age, the necessity to provide an appropriate drug formulation, the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic particularities, and the parent's intervention. All stakeholders, including governmental agencies, drug companies, funding institutes, research centers, decision-makers, hospitals, and clinicians, should make sure they work altogether to support and facilitate drug research in children. For instance, such collaboration has taken the form of pediatric research networks developed to improve health in pediatrics, by conducting multi-institutional studies, supporting research collaboration, and encouraging informational exchanges between healthcare providers. The European Network of Paediatric Research (2011) at the EMA33 and the National Pediatric Research Network at the FDA (2013)34 are examples of governmental initiatives. The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network,35 the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings,36 and the Australian Paediatric Research Network37 have emerged from health care provider initiatives. Also, drug monographs are based on studies conducted at the time of drug development, and most of them are not updated based on current clinical practice. Therefore, it seems that off-label drug use is more prevalent with older drugs.

Effect of Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Uses

Given the prevalence of unlicensed and off-label drug use, it is important to evaluate the impact of such issues. Few studies that have analyzed the effect of unlicensed and off-label drug use on administrative and clinical outcomes. In 2004, the EMA published a report on the evidence of harm associated with the use of unlicensed and off-label drug use in children.38 The major potential harm reported was the increase in adverse drug reactions, followed by an increased risk of medication errors associated with insufficient labeling. The report also stated that “prospective monitoring of ADRs [adverse drug reactions] indicates higher incidence and in particular shows up to double incidence when including both clinical and laboratory parameters detection.” Of the studies included in our review, only 2 reported ADRs associated with unlicensed and off-label drug uses. In 1999, Turner et al9 reported that 3.9% of licensed drugs were associated with an ADR compared with 6% with unlicensed and off-label drugs. In 2013, Ballard et al32 reported 5 ADRs in their study, and 2 of these were associated with an off-label drug use. Regarding these results, it seems important to prospectively monitor efficacy and ADR to ensure patients safety.

Actions to Decrease Unlicensed and Off-Label Drug Uses

These results demand action. Although it is certainly impossible to eliminate unlicensed and off-label drug use in children, progress should be made. In a 2014 report of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology about the prescription of pharmaceuticals in Canada has shed some light on unlicensed and off-label drug use.39 The committee formulated 18 recommendations that constitute a good action plan. Their recommendations included the implementation of electronic medical record, the necessity to inform patients of unlicensed and off-label prescription drug use, the implementation of an online ADR form with required information, the identification and the evaluation of common off-label uses, the sharing of information between jurisdiction, the need for more drug research in vulnerable subgroups of the population, the monitoring of some therapeutic classes (e.g. antipsychotics), the standardization of formulary listings, research on off-label older drugs, and the examination of the current prohibition on off-label drug promotion by manufacturers. Although we support most of these recommendations, we believe drug manufacturer promotion should be limited to their contribution to clinical research and their drug monograph.

In 2014, the Council of Canadian Academies published its report40 on improving medicines for children in Canada. In that report, the council identified 5 key findings about the lack of medicines available for pediatric use. They stated that most drugs used in children haven't been proven safe and effective. Nonetheless, all drugs should be studied in children because pediatric clinical research is possible and safe. Moreover, the council also encouraged Health Canada to learn from governmental initiatives in both the United States and Europe, which encourage, require, and monitor pediatric clinical research.

Limits

This literature review has some limitations. The aim of this literature review was not to evaluate the effect on pediatric clinical research but to assess the positive effect of these regulations on the prevalence of unlicensed and off-label drug use. Definitions used to describe unlicensed and off-label drug use differed among studies. For instance, unlicensed drug use, in some studies, included the modification of a marketed formulation (e.g., a suspension compounded from tablets by the pharmacists) to offer a more suitable product to administer to a child8,9,11,13,15–20,24,26,28,31 and added confusion to their definition of unlicensed drug use by including off-label drug uses.14,23,30 Health care settings studied to identify unlicensed and off-label drug use also varied among studies, including inpatients and outpatients settings, but also different target populations (e.g., adult, pediatric, mixed). Although regulatory changes by the FDA and EMA might affect the whole world, at some point, because of these agencies' pivotal roles in drug approval, it is reasonable to speculate that doing so may take at least another decade to affect most countries and to significantly decrease off-label drug use.

CONCLUSION

The comparison of before and after initiatives on unlicensed and off-label drug use rates in Europe showed that, at this point, governmental initiatives to improve clinical research conducted in children seemed to have had a marginal effect in decreasing unlicensed and off-label drug use prevalence. Implementing most of the recommendations in the report of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology for the prescription of pharmaceuticals in Canada would be a good start toward continuing the effort to decrease the use of unlicensed and off-label drugs.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADR

adverse drug reaction

- BPCA

Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- EU

European Union

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- FDAMA

FDA Modernization Act

- PREA

Pediatric Research Equity Act

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997—FDA Backgrounder on FDAMA. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFood-DrugandCosmeticActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDAMA/ucm089179.htm. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 2.Food and Drug Administration. Significant Amendments to the FD&C Act—Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmeti-cActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/ucm148011.htm. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 3.Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/UCM077853.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 4.European Medicines Agency. On Medicinal Products for Paediatric Use. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2006_1901/reg_2006_1901_en.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 5.Government of Canada HC. Paediatric Expert Advisory Committee (PEAC)—Health Canada. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/branch-dirgen/hpfb-dgpsa/opi-bip/peaccceip/index-eng.php. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 6.McKinzie JP, Wright SW, Wrenn KD. Pediatric drug therapy in the emergency department: does it meet FDA-approved prescribing guidelines? Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15(2):118–121. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021–1026. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner S, Longworth A, Nunn AJ, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards: prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316(7128):343–345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner S, Nunn AJ, Fielding K, Choonara I. Adverse drug reactions to unlicensed and off-label drugs on paediatric wards: a prospective study. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88(9):965–968. doi: 10.1080/08035259950168469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.‘t Jong GW, Vulto AG, de Hoog M et al. Unapproved and off-label use of drugs in a children's hospital. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(15):1125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries: European Network for Drug Investigation in Children. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):79–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalumeau M, Treluyer J, Salanave B et al. Off label and unlicensed drug use among French office based paediatricians. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(6):502–505. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.6.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntyre J, Conroy S, Avery A et al. Unlicensed and off label prescribing of drugs in general practice. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(6):498–501. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.6.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.‘t Jong GW, Eland IA, Sturkenboom MCJM et al. Unlicensed and off label prescription of drugs to children: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2002;324(7349):1313–1314. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7349.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schirm E, Tobi H, de Jong-van den Berg LTW. Unlicensed and off label drug use by children in the community: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2002;324(7349):1312–1313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7349.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandolfini C, Impicciatore P, Provasi D. Off-label use of drugs in Italy: a prospective, observational and multicentre study. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91(3):339–347. doi: 10.1080/08035250252834030. et al; Italian Paediatric Off-label Collaborative Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick A, Keady S, Mohamed F et al. Use of unlicensed and off-label medications in paediatric gastroenterology with a review of the commonly used formularies in the UK. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(4):571–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.López Martínez R, Cabañas Poy MJ, Oliveras Arenas M, Clemente Bautista S. Drug use in a neonatal ICU: a prospective study [in Spanish] Farm Hosp. 2005;29(1):26–29. doi: 10.1016/s1130-6343(05)73632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dell'Aera M, Gasbarro AR, Padovano M et al. Unlicensed and off-label use of medicines at a neonatology clinic in Italy. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29(4):361–367. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindell-Osuagwu L, Korhonen MJ, Saano S et al. Off-label and unlicensed drug prescribing in three paediatric wards in Finland and review of the international literature. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34(3):277–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsson J, Kimland E, Pettersson S, Odlind V. Paediatric drug use with focus on off-label prescriptions in Swedish outpatient care—a nationwide study. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(9):1272–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruíz-Antorán B, Piñeiro R, Avendaño C et al. Drug utilization and off-label drug use in Spanish pediatric gastroenterology outpatients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(2):173–177. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182566d92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langerová P, Vrtal J, Urbánek K. Incidence of unlicensed and off-label prescription in children. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40:12. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-40-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laforgia N, Nuccio MM, Schettini F et al. Off-label and unlicensed drug use among neonatal intensive care units in Southern Italy. Pediatr Int. 2014;56(1):57–59. doi: 10.1111/ped.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carnovale C, Conti V, Perrone V et al. Paediatric drug use with focus on off-label prescriptions in Lombardy and implications for therapeutic approaches. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(12):1679–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavrilov V, Lifshitz M, Levy J, Gorodischer R. Unlicensed and off-label medication use in a general pediatrics ambulatory hospital unit in Israel. Isr Med Assoc. 2000;2(8):595–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Donnell CPF, Stone RJ, Morley CJ. Unlicensed and off-label drug use in an Australian neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):e52. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bajcetic M, Jelisavcic M, Mitrovic J et al. Off label and unlicensed drugs use in paediatric cardiology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(10):775–779. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Paolo ER, Stoetter H, Cotting J et al. Unlicensed and off-label drug use in a Swiss paediatric university hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13–14):218–222. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dos Santos L, Heineck I. Drug utilization study in pediatric prescriptions of a university hospital in southern Brazil: off-label, unlicensed and high-alert medications. Farm Hosp. 2012;36(4):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.farma.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JL, Redzuan AM, Shah NM. Unlicensed and off-label use of medicines in children admitted to the intensive care units of a hospital in Malaysia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(6):1025–1029. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballard CDJ, Peterson GM, Thompson AJ, Beggs SA. Off-label use of medicines in paediatric inpatients at an Australian teaching hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(1):38–42. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Medicines Agency. European Network of Paediatric Research at the European Medicines Agency (Enpr-EMA) http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/partners_and_networks/general/general_content_000303.jsp. Accessed April 22, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.US 113th Congress. HR225: National Pediatric Research Network Act of 2013. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/225. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 35.Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network. What is PECARN? http://www.pecarn.org/. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 36.Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting. About Us. http://www.prisnetwork.org/. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 37.Australian Paediatric Research Network. What is the APRN. http://www.aprn.org.au/aboutus. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 38.European Medicines Agency. Evidence of harm from off-label or unlicensed medicines in children. 2004. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2009/10/WC500004021.pdf. Published October 2004. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 39.Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Prescription pharmaceuticals in Canada: off-label use [in French] http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/412/soci/rep/rep05jan14-f.pdf. Published January 2014. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 40.Improving Medicines for Children in Canada. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Council of Canadian Academies; 2014. Expert Panel on the State of Therapeutic Products for Infants, Children, and Youth. [Google Scholar]