In 1971 President Richard Nixon declared a war on cancer and signed the National Cancer Act. During the past several decades since this declaration, the nation has made extraordinary progress toward a far better understanding of the molecular, cellular, and genetic changes resulting in cancer. We have also seen significant declines in overall and site-specific cancer mortality1. This decline in mortality has been attributed to improved cancer prevention, screening, and detection measures as well as the application of more effective and more targeted cancer treatments.

However, some Americans (such as the poor, uninsured, and underinsured) have not shared sufficiently in this progress as measured by higher mortality, lower survival, and 5-year cancer survival2, 3. These findings suggest that there is a disconnect between the nation’s discovery and delivery enterprises; a disconnect between what we know and what we do (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Discovery-Delivery Disconnect

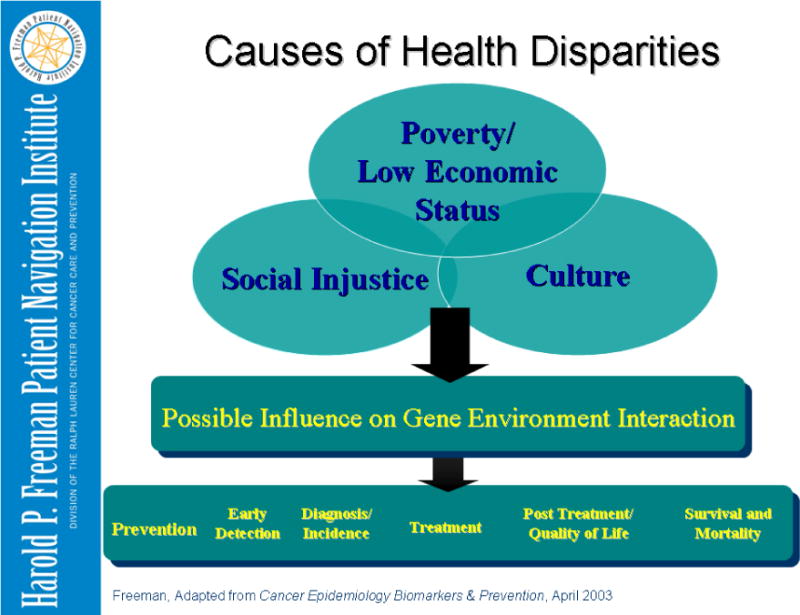

Disparities occur when beneficial medical interventions are not shared by all. Moreover, health disparities arise from a complex interplay of economic, social, and cultural factors. The model presented in (Fig. 2) illustrates the overlapping factors of poverty, culture, and social injustice as principal causes of health disparities. These causal factors impact on all aspects of the healthcare continuum from prevention, detection, diagnosis, treatment, and survival to the end of life. Disparities occur principally in individuals or populations who experience one or more of the following circumstances: insufficient resources, risk-promoting lifestyle and behavior, and social inequities. Approaches to reducing or eliminating disparities must necessarily take these factors into consideration.

Figure 2.

Causes of Health Disparities

Poverty as a Cause of Cancer Disparities

Poverty is associated with low educational level, substandard living conditions, inadequate social support, unemployment, risk-promoting lifestyle, and diminished access to healthcare. According to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau report, in 2009 there were 43.6 million (14.3%) poor Americans. This represents an increase of 4 million poor Americans compared to 2008. Among all men and women, the 5-year survival for all cancers combined is 10% lower in the poor than in more affluent Americans. Additionally in 2009, an estimated 50.7 Americans (16.7%) were without health insurance coverage.

Patient Navigation

Patient navigation is a community-based service delivery intervention designed to promote access to timely diagnosis and treatment of cancer and other chronic diseases by eliminating barriers to care. The development of the concept of patient navigation was related to the findings of the American Cancer Society National Hearings on Cancer in the Poor. The hearings were conducted in 1989 in seven American cities. The testimony was primarily by poor Americans of all races and ethnic groups who had been diagnosed with cancer.

Based on these hearings, the American Cancer Society issued a “Report to the Nation on Cancer in the Poor” in 1989. The report found that the most critical issues related to cancer and the poor are:

Poor people face substantial barriers in seeking and obtain cancer care and often do not seek care if they cannot pay for it.

Poor people endure greater pain and suffering from cancer than other Americans.

Poor people and their families often make extraordinary personal sacrifices to obtain and pay for care.

Fatalism about cancer is prevalent among the poor and may prevent them from seeking care.

Current cancer education programs are culturally insensitive and irrelevant to many poor people.

Related to these findings, the nation’s first patient navigation program was conceived and initiated in 1990 in Harlem, New York by Dr. Harold Freeman. This original program focused on the critical window of opportunity to save lives from cancer by eliminating barriers to timely care between the point of a suspicious finding and the resolution of the finding by further diagnosis and treatment.

Commonly experienced barriers to timely care are:

Financial and access barriers, such as no health insurance

Communication and information barriers

Medical system barriers

Fear, distrust, and emotional barriers

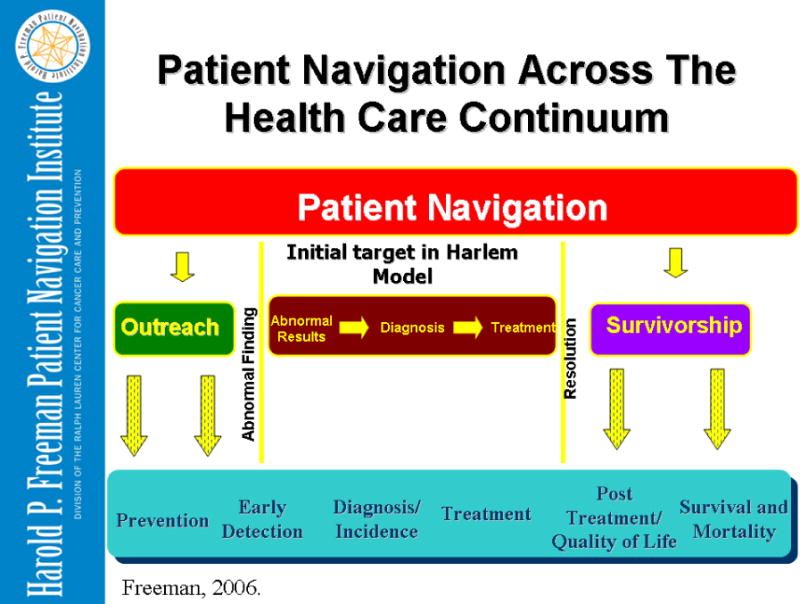

Subsequently, the scope of patient navigation, (Figure 3) has been expanded to be applied across the entire health care continuum including prevention, detection, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship to the end of life.

Figure 3.

Current Patient Navigation Model

The Harlem Breast Cancer Experience

Before intervention, in a 22-year period ending in 1986, 606 patients (94% black) with breast cancer were treated at Harlem Hospital Center in New York City4. All patients were of low economic status and half had no medical insurance on initial visit. The results were as follows: only 6% of these patients had stage 1 disease. The five-year survival rate was 39%.

After intervention the results were dramatically improved. The intervention consisted of two elements: providing free and low-cost examinations/mammograms according to recommended guidelines; and patient navigation to assure that all patients received timely diagnosis and treatment. The results were as follows: of 325 breast cancer patients, 41% of patients had early breast cancer (stage 0 and 1). The five-year survival was 70%.

Two major factors are believed to account for these dramatically improved results achieved in a population of disproportionately poor and uninsured patients in Harlem: providing free/low-cost breast examinations, which led to early diagnosis, and patient navigation, which assured timely diagnosis and treatment.

Based principally on the patient navigation model in Harlem, the Patient Navigator and Chronic Disease Prevention Act (HOUR 1812) was passed by the Congress and signed into law by President Bush in 2005. A total of 20 patient navigation demonstration sites have been funded by three different government agencies The American College of Surgeons has determined that patient navigation will soon be a required standard for cancer center approval by the Commission on Cancer.

The Principles of Patient Navigation

The momentum that patient navigation has received as a community-based intervention (which has expanded and been transformed into a nationally recognized model) has stimulated the need to define principles and standards for patient navigation. Below are listed the Principles of Patient Navigation that have been developed and vetted for more than 20 years through the authors’ experience.

Principles

-

Navigation is a patient-centric healthcare service delivery model.

The focus of navigation is to promote the timely movement of an individual patient through an often complex healthcare continuum. An individual’s journey through this continuum begins in the neighborhoods where he or she lives, to a medical setting where an abnormality is detected, a diagnosis is made, and then through treatment, rehabilitation, and survivorship to the end of life. As patient care is so often delivered in a fragmented fashion, particularly related to those with chronic diseases, patient navigation has the potential of creating a seamless flow for patients as they journey through the care continuum. Patient navigation can be seen as the guiding force promoting the timely movement of the patient through a complex system of care.

-

The core function of navigation is the elimination of barriers to timely care across all segments of the healthcare continuum.

This function is most effectively carried out through a one-on-one relationship between the navigator and the patient.

Patient Navigation should be defined with a clear scope of practice that distinguishes the role and responsibilities of the navigator from that of all other providers. Navigators should be integrated into the healthcare team in such a way that there is maximum benefit for the individual patient.

Delivery of navigation services should be cost-effective and commensurate with the training and skills necessary to navigate an individual through a particular phase of the care continuum.

-

The determination of whom should navigate should be primarily decided by the level of skills required at a given phase of navigation.

There is a spectrum of navigation extending from services that may be provided by trained lay navigators to services that require navigators who are professionals, such as nurses and social workers. Another principle to take into account is that healthcare providers should ideally provide patient care that requires their level of education and experience; they should not be assigned to duties that do not require their skills.

There is a need in a given system of care to define the point at which navigation begins and the point at which navigation ends. We must keep in mind that for the cancer patient involved, the need is not over until the cancer is resolved.

There is a need to navigate patients across disconnected systems of care, such as primary care sites and tertiary care sites Patient navigation can serve as the process that connects disconnected healthcare systems.

Navigation systems require coordination. In larger systems of patient care this coordination is best carried out by assigning a navigation coordinator or champion who is responsible for overseeing all phases of navigation activity within a given healthcare site.

Contributor Information

Harold P. Freeman, Email: hfreeman@mail.nih.gov.

Rian L. Rodriguez, Email: rlrodriguez@ralphlaurencenter.org.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007 Jan 1;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roetzheim RG, Gonzales EC, Ferrante JM, et al. Effects of health insurance and race on breast carcinoma treatments and outcomes. Cancer. 2000;89(11):2202–2213. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2202::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oluwole SF, Ali AO, Adu A, et al. Impact of a cancer screening program on breast cancer stage at diagnosis in a medically underserved urban community. J Am Coll Surg. 2003 Feb;196(2):180–188. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01765-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]