Abstract

In this manuscript we discuss the interaction of the lung parenchyma and the airways as well as the physiological and pathophysiological significance of this interaction. These two components of the respiratory organ can be thought of as two independent elastic structures but in fact the mechanical properties of one influence the behavior of the other. Traditionally the interaction has focused on the effects of the lung on the airways but there is good evidence that the opposite is also true, i.e., that the mechanical properties of the airways influence the elastic properties of the parenchyma. The interplay between components of the respiratory system including the airways, parenchyma and vasculature is often referred to as “interdependence.” This interdependence transmits the elastic recoil of the lung to create an effective pressure that dilates the airways as transpulmonary pressure and lung volume increase. By using a continuum mechanics analysis of the lung parenchyma, it is possible to predict the effective pressure between the airways and parenchyma, and these predictions can be empirically evaluated. Normal airway caliber is maintained by this pressure in the adventitial interstitium of the airway, and it counteracts airway compression during forced expiration as well as the ability of airway smooth muscle to narrow airways. Interdependence has physiological and pathophysiological significance. Weakening of the forces of interdependence contributes to airway dysfunction and gas exchange impairment in acute and chronic airway diseases including asthma and emphysema.

1. Introduction

When the lung is inflated, the pressure in the alveoli must exceed that outside the visceral pleura. This transmural pressure is referred to as the transpulmonary pressure (Ptp). In a normal healthy lung this transmural pressure is applied to all alveoli, even those completely surrounding by other alveoli. The process by which such internal alveoli inflate also applies to the enlargement of bronchi and blood vessels (except alveolar wall capillaries) within the parenchyma, and this effect on airways was first noted in 1915 by Rohrer (68) and later in 1946 by Macklin (50). Rohrer states, “…since the expanding force in the lung… spreads uniformly in all directions, the bronchi, being everywhere coalescent with the parenchyma, also undergo a corresponding radial pull, so that if we were dealing with homogeneous elastic pipes, we would see a uniform change in length and diameter.” Although this homogeneous expansion suggests a transmission of pleural pressure internally, the magnitude of the forces involved in expanding internal regions of parenchyma in addition to the airways and blood vessels under nonhomogeneous conditions is not intuitively obvious. Early experiments to quantify these forces were made in 1961 by a group led by Sol Permutt. These investigators confirmed the findings of Macklin (33) and published two papers that focused on how the blood vessels are affected when the lung is inflated (32, 66). By separating the effects on large and small vessels, they arrived at the conclusion that, while the capillaries in the alveolar septa were compressed by lung inflation, the larger vessels were dilated. Since large airways travel within the same interstitial space and immediately adjacent to the arteries, these airways are subjected to the same distending forces with lung inflation.

However, it wasn’t until 1970, that this concept was put on a more solid conceptual and quantitative foundation (55). In a landmark paper, Mead and colleagues (55) showed that the effective pressure around regions surrounded by parenchyma was approximately equal to pleural pressure (Ppl), but could deviate from pleural pressure under certain conditions. With several simplifying assumptions, they were able to obtain quantitative estimates on how large this subpleural pressure might be around bronchi, blood vessels, and obstructed regions of parenchyma. Soon thereafter, Wilson established a firm theoretical basis for this phenomenon, by putting it in the context of a continuum mechanics analysis, which treats the lung as an elastic matrix (85). This theoretical approach provided quantitative estimates of the Young’s and shear moduli of this elastic continuum. The model was later tested and evaluated in a series of studies by Lai-Fook and associates, who examined the relationship between changes in the volume of the parenchyma and of the airways and blood vessels within (42, 44, 45). This work showed that the lung parenchyma was very easily distorted, with a parenchymal shear modulus on the order of 0.7 × transpulmonary pressure. It is often not appreciated just how low this value of shear modulus is, and what its impact is on the airways. For example, although the airways are clearly affected by the state of lung inflation, in a normal lung, the pressure surrounding an intraparenchymal airway with relaxed airway smooth muscle, is within 1 cmH2O of the pleural pressure (44). This indicates that the airway diameter would be virtually the same if the parenchyma could be somehow completely removed from around the airway, so that the airway itself was surrounded by Ppl. As the lung is inflated in vivo, the effective pressure outside the airways (defined as Px) will decrease (i.e., tracking the decrease in Ppl). Thus, during a deep inspiration, the airways will dilate, but when the lung returns to FRC, the pressure around the airway will remain at a level very close to pleural pressure. This central role of pleural pressure, or more precisely elastic recoil pressure, was highlighted by a number of early studies by Caro, et al and Stubbs and Hyatt, that clearly demonstrated that the diameter of the intraparenchymal airways was entirely dependent on lung recoil pressure and relatively independent of lung volume (14, 76). The anatomical arrangement being considered in this review is shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the lung inside the thorax and the airway tree inside the lung. The dimensions of the pleural space between the lung and chest wall and the interstitial/adventitial space between the lung parenchyma and airway lumen are greatly exaggerated for clarity. For the results of Caro, et al and Stubbs and Hyatt to be correct, the pressures in the latter space would be equal to pleural pressure.

Figure 1.

Drawing showing the structures that balance the inward recoil of the lung. The contiguous intrapleural and interstitial virtual spaces (in light blue) are shown greatly enlarged for clarity. The inward recoil of the inflated lung (shown by the arrows) is supported by the outward recoil of the thoracic wall and the inward recoil of the airway tree. The interstitial pressure between the airways and parenchyma (Px) is normally very close to the pressure in the intrapleural space, Ppl.

Although the concept of inhomogeneity is an important special case in relation to parenchymal interdependence, with regard to the interaction between the tubular airway tree structure and the isotropic parenchyma, it would seem that inhomogeneity should be the normal case. That is, the concept of homogeneity between the airways and parenchyma would only exist if the 3 dimensional airway tree behaved exactly the same as if the tree structure was comprised solely of lung parenchyma. Although it is unlikely that the airway tree’s mechanical properties would perfectly match the mechanical properties of lung parenchyma, the situation is not that far removed from such perfect homogeneity in a normal lung. In addition to the work of Caro, et al (14), and Stubbs and Hyatt (76) cited above, Mead et al in their classic paper did a quantitative analysis, based on parenchymal and airway pressure volume curves derived from published papers (55),. Their results are reproduced in Figure 2. This figure shows that there was very little predicted difference between the distensibility of an airway in situ and excised. Thus, they concluded that the airways behaved as though they were homogenously matched to the parenchyma. However this is an oversimplified interpretation for several reasons. First, the fact that the pressure volume behaviors have such markedly different shapes must impose a limit on the pressure (or volume) range where homogeneity can be assumed. Second, they only did their analysis for large airways with no smooth muscle tone The airway pressure-area curves are known to be substantially different when there is active smooth muscle tone (8), and since there is always some degree of airway smooth muscle tone, the issue of heterogeneity becomes more relevant in vivo. In the rest of this manuscript we will discuss the work that has been done since this paper by Mead et al, to understand what happens when such inhomogeneities develop, and how these changes ultimately affect the resistance of the airway tree.

Figure 2.

Volume versus transpulmonary pressure curves for dog lung (upper solid line), excised dog bronchus (lower solid line) and the predicted curve for the same bronchus in situ. This analysis illustrates three points. Firstly the large bronchi are considerably less distensible than the lung, at least over this whole pressure range. The bronchial volume increases ≈3 fold while the lung volume increases ≈8 fold going from a Ptp of zero to 20 cmH2O. Secondly the maximal bronchial volume is reached at a much lower transpulmonary pressure than is the maximal lung volume (the plateau on the bronchial volume pressure curve is achieved at a Ptp of ≈8 cm H2O). Finally the analysis shows that the in situ bronchus behaves almost exactly as if the Ptp is the effective distending pressure. The deviation of the solid (excised) and in situ (dashed) bronchial volume-pressure curves represents the small difference between transpulmonary and transairway pressure due to the difference between pleural and interstitial pressure. Adapted from Mead et al (55).

Anatomic considerations

The interdependence between the airways and parenchyma depends on several anatomic considerations. Although it is well known that there is a well-defined elastic membrane in the mammalian bronchial tree, these elastic fibers only run axially in the tunica propria inside the smooth muscle layer (51). The fibers are continuous from the trachea all the way down to the smallest airways, and as noted by Macklin, they may make an important contribution to the recoil of the whole lung. Bundles of these fibers are also the likely sites that initiate the characteristic mucosal folds seen in contracted airways (74, 82). However, it is important to emphasize that there are relatively few isolated fibers that run circumferentially or radially, so that for airways embedded in the parenchyma, there are no radial fibers tethering the airways and the surrounding parenchyma. The outer adventitial layer of the airway merges with an interstitial space that ends in alveolar walls. One way of thinking about the pressure within this interstitial space between airways and parenchyma is by analogy with the pressure around the lung between the visceral pleura and the chest wall, as shown in Figure 1. The pressure between visceral and parietal pleurae is the pleural pressure, and inside the lung, there is an equivalent parenchymal boundary that defines the space containing the airway tree, and we refer to this as the internal parenchymal boundary. In the large central airways of larger mammals this boundary consists of the visceral pleural membrane invaginated into the parenchyma, but in the smaller airways and in all airways of smaller species such as rats or mice, it consists simply of alveolar walls. This is illustrated in a 2 mm airway shown in Figure 3. This figure also emphasizes the absence of any radial structural fibers between this internal parenchymal boundary and the airway. Continuing with this analogy, the effective pressure between this internal parenchymal boundary and the airway is produced by the same forces that determine the pleural pressure, i.e., the inward recoil of the airway tubes that is balanced in this case by the outward recoil of the lung parenchyma, as illustrated by the arrows in Figure 1. Therefore, in both cases it is clear that the recoil of the lung plays a key role – anything that reduces the lung's recoil, must result in a larger lung and smaller airways. The question to be considered with regard to airway-parenchymal interdependence is thus reduced to determining the effective pressure outside this internal parenchymal boundary.

Figure 3.

Histologic section of small canine airway, showing the attachments of alveoli that also form the outer boundary of the airway. Bar is 0.5 mm.

As emphasized in Figure 1, the interstitial space between airways and parenchyma is analogous to the virtual pleural space between the lung and chest wall. In a normal lung, these are almost virtual spaces, with very little pleural fluid and very little interstitial fluid. However, with the development of pulmonary edema (analogous to a pleural effusion), this virtual space can enlarge considerably with the accumulation of excess fluid (81). This potential space is often called the peribronchial space. This term, however, is misleading since the prefix “peri” implies that the space is outside of some well-defined internal airway boundary. As Figure 3 shows, the only well-defined boundary is the border formed by the alveolar walls, and when edema fluid exists it is located inside this border. Thus the outer adventitial airway layer is equivalent to the interstitial space, and the pressure in this outer adventitial space (Px), relative to luminal airway pressure, will determine the transmural pressure of the airway, that directly affects airway luminal diameter as the lung is inflated or deflated.

In addition to the stresses that function to dilate airways, the airways also must lengthen with lung inflation. Since the distal end of the airways is by definition the parenchyma (i.e., alveolar walls), as the lung expands, the airway tree must lengthen in proportion to the cube root of lung volume. This fact was noted by Macklin (52), who stated, “with a rigid bronchial tree respiration would be impossible.” The effect of this lengthening on airway diameter is not entirely clear. Early in vitro work by Hyatt and Flath (33), somewhat surprisingly, suggested that stretching an airway in the axial direction had a negligible effect on its radial distensibility. The effect of this lengthening in the intact lung remains uncertain, since one cannot study airway pressure-diameter relations in situ without inflating the lung. Although the lengthening of airways with lung inflation would by itself increase resistance, the dominant effect of inflation is to lower resistance by increasing luminal diameter. This is because airway resistance is inversely related to the 4th power of airway diameter but linearly related to airway length. This effect of lung volume on airway resistance is important physiologically and pathophysiologically, and thus the effective pressure around the airways assumes a key role. There have been several theoretical and experimental assessments of the effective pressure in the airway interstitial space, which will be discussed later. However as already noted, at static lung volumes near FRC when the smooth muscle is relaxed, Px is very close to pleural pressure, and this means that the distending transmural pressure for the airway is about the same as the transpulmonary pressure. This was defined by Mead et al as the homogeneous state (55). As the lung inflates, this trans-airway pressure could theoretically become greater or smaller than the transpulmonary pressure, depending on the relative distensibility of the airways and parenchyma, and much of the work involved with airway-parenchymal interdependence has been focused on what happens during such maneuvers.

It is clear that structural alterations in the lung parenchyma can affect the airway size in more than one way. For example if the lung loses elasticity as happens in emphysema, the Ppl will be less negative at any lung volume. This by itself would lead to a smaller transmural airway pressure (and hence smaller airways), but the loss of elasticity in the lung may also lead to increased lung volume, which could increase the size of the holes in the parenchyma where the airways fit (see below). Similarly, structural or functional changes in the airways can influence their interaction with the parenchyma. Airways can narrow because of airway smooth muscle (ASM) contraction and/or airway wall remodeling. ASM contraction and airway remodeling may also lead to increased airway stiffness so that Px can become more subatmospheric than Ppl as the lung inflates. In considering such inhomogeneities, Mead, et al (55) stated that whenever such inhomogeneities are introduced, the forces of interdependence change so as to reduce those inhomogeneities. As such, the forces of interdependence are rectifying forces that tend to lessen heterogeneity in distribution of ventilation.

1. The normal lung

As mentioned above, the interdependence between parenchyma and airways generates the pressure around the airways that determines how airway caliber and resistance change with lung volume. Normal tidal breathing and, especially periodic deeper inspiration (DI), such as yawns and sighs, dilate the airways. How much the airway resistance decreases is dependent on the balance between the elastic recoil properties of the lung, the linkage (interdependence) between the lung and the airways, and the stiffness of the airways. The stiffness of the bronchial tree can be influenced acutely by smooth muscle contraction and chronically by airway remodeling. Vincent and colleagues measured the volume dependence of pulmonary resistance in normal humans (80). (Figure 4) They found that the relationship between airway resistance and lung volume is approximately hyperbolic, with resistance falling on average about 60% when going from FRC (≈3 L) to TLC (≈6.5 L). A 60% fall in airway resistance could be effected with a 25% increase in average diameter, and if as a first approximation we assumed that airway diameter increased proportional to the cube root of lung volume (i.e., geometrically similar), this resistance change is within the range of what one would expect. In addition, the study by Vincent, et al (80) showed that there was hysteresis of resistance in the presence of tone, with airway resistance being higher during inflation than during deflation at any lung volume. When tone was diminished by the administration of atropine hysteresis was substantially decreased, but not abolished, This observation indicates that ASM tone is an important contributor to airway area-pressure hystereis but that tissue and/or surface forces must also contribute.

Figure 4.

Pulmonary resistance plotted against lung volume (percent vital capacity) during inflation (interrupted lines) and deflation (solid lines) before (left panel) and after (right panel) administration of atropine. Prior to atropine, resistance decreases as lung volume increases but there is considerable hysteresis such that resistance is lower at any lung volume after inflation. Following abolition of airway smooth muscle tone with atropine there is both a decrease in resistance and an attenuation of hysteresis. Adapted from Vincent NJ et al.(80).

If the inflation-deflation behaviour of the airways and lung were perfectly matched, the two structures would inflate and deflate homogenously and Ptp and airway transmural pressure (Ptm = intrabronchial pressure (Paw) – Px) would always be the same as Ptp. The only way for this to happen would be if Px were always the same as pleural pressure. Such a situation can be imagined with a thought experiment, where the airway wall and lumen are replaced with a cylinder filled with normal parenchyma in which the outer edge conforms to the former outer boundary of the airway. Under such conditions “airway diameter” will vary as the cube root of changes in lung volume. To the extent that the actual airway behaves differently from parenchyma, then Px will deviate from Ppl. The situation in vivo is further complicated both by the fact that the mechanical response of airways to inflation is dominated by smooth muscle tone, and the response of the parenchyma is dominated by surface and tissue forces. Thus the airways and parenchyma are affected by different physical factors, and the magnitude of this deviation will be determined by the relative elasticities of both the airways and the parenchyma.

Although the literature concerning lung-airway interdependence is dominated by consideration of how changes in the lung affect the airways, the reciprocal of this relationship has equally important implications, i.e., changes in the mechanical properties of the airway tree can influence the behavior of the lung parenchyma. This side of the equation was evaluated by Mitzner and colleagues (37), who infused a solution of methacholine directly into the bronchial artery of sheep to perfuse and contract only the conducting airways. There was no constriction of peripheral lung units (respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts), yet they observed a substantial reduction in dynamic and static lung compliance. They considered a number of possible mechanisms for this finding including the development of airway closure and axial stiffening of the tracheal bronchial tree (i.e., impeding airway lengthening). They concluded that the most likely explanation is that contraction of ASM stiffens the airway tree, making both its axial extension and alterations in branching angles more difficult. The important implications of this finding are that contraction of airway smooth muscle in conducting airways can decrease lung compliance and increase tissue viscous resistance, both of which make up a substantial portion of pulmonary impedance.

In an attempt to test the importance of deformation and lengthening of the tracheobronchial tree on lung compliance one of us (WM) conducted an experiment to stiffen the tree by injecting methacrylate resin into the pulmonary arteries of a dog lung (unpublished observations). On hardening the methacrylate made a virtually non-deformable cast of the vascular tree down to arteries adjacent to 2 mm airways (visualized after digesting the lung tissue). Since the vascular tree is coupled to the airway tree within the bronchovascular space, stiffening the vascular tree and preventing its lengthening also prevented the lengthening of the airway tree. The resultant stiffening of the lung was substantial, and the difficulty of inflation supports the prediction of Macklin (52)

Continuum mechanics analysis

Assuming the lung to be an isotropic medium, it’s elastic behaviour in response to applied forces can be described by two moduli, the bulk and shear moduli. The bulk modulus of a substance is a measure of the substance's resistance to uniform expansion or compression. (Figure 5) The bulk modulus is equivalent to the elastance normalized to the lung volume at which it is measured (i.e., specific elastance), and thus, it can be obtained directly from a pressure volume curve. However, to obtain the shear modulus, the lung shape has to be distorted (Figure 5). The shear modulus is defined as the ratio of the applied shear stress to the ensuing shear strain. The shear modulus of the lung has been estimated by indenting the pleural surface of the lung inflated to variety of transpulmonary pressures and measuring the surface indentation as a function of the applied force (28, 45). The dimensions of the bulk and shear moduli are the same as for pressure (force per unit area) and the results show a value for the shear modulus of ~0.7Ptp, while the bulk modulus ranges from 3Ptp to 7Ptp as the lung volume changes from 20% to 80% of the total lung capacity (43, 77). This means that it is much easier to distort lung’s shape than to inflate the lung.

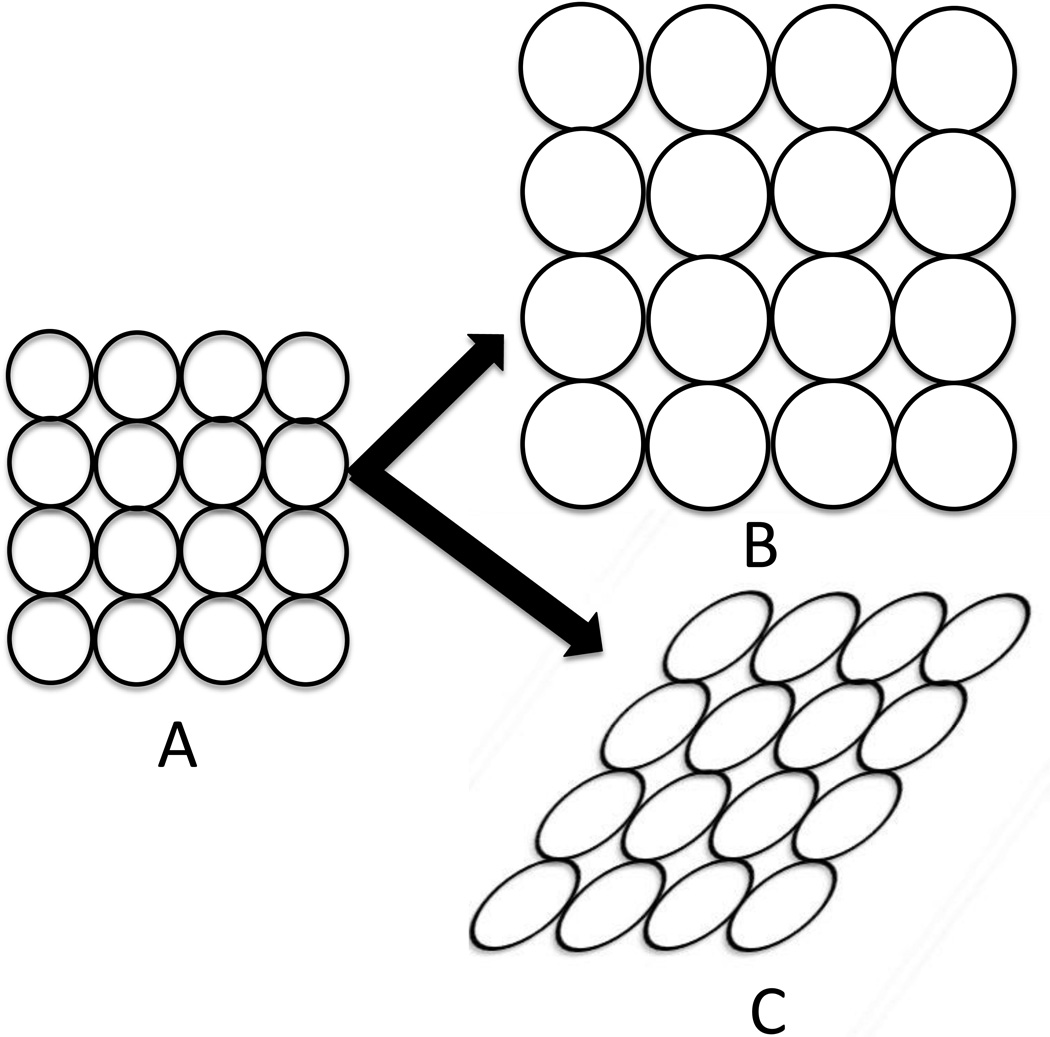

Figure 5.

Illustration of the difference between uniform expansion of the lung and shear strain. A is a region of lung which can be uniformly expanded (B) or distorted (C). The bulk modulus is a measure of the lung’s resistance to uniform expansion and is defined as the pressure needed to cause a given relative increase in volume. The shear modulus is a measure of the lungs resistance to shape change without a change in volume.

If the airways do not have the same distensibility as the surrounding parenchyma, then the parenchyma around the airways (and the airways themselves) must deform (undergo shear) when lung volume is changed. The relationship between this parenchymal deformation and the deviation of interstitial pressure (Px) from Ppl with a change in lung volume is directly proportional to the shear modulus of the lung. This relation can be determined from the equation defining ΔPx, i.e.,

| Equation 1 |

where where ΔPx = Px – Ppl, µ = the shear modulus of the lung parenchyma, Do = the predicted diameter of the hole in the parenchyma were there no airway present, and ΔD is the deviation of the actual diameter from Do. Thus if ΔPx < 0, then ΔD < 0 and the airway diameter decreases and vice versa if ΔPx > 0.

It is difficult to glean intuitive insight from this equation, since there is an interaction between µ and ΔD. For example if the parenchymal shear modulus were to increase then the ΔD would decrease, so without more specific quantitative information, the magnitude of the resultant change in Px would be difficult to predict. However, if shear modulus is very small then even large inflations might result in little change in Px, and the airways will behave as if they were outside the parenchyma, i.e., surrounded by pleural pressure. Of course larger changes in Px can occur during ASM contraction, which produces larger values for ΔD.

A simple analogy of the inter-relatedness of the parenchyma and airways is the way the lung and chest wall inflate together; the pleural pressure between them is analogous to Px. An increase in the volume of the chest wall will result in a more negative pleural pressure and when the lung is stiffer, this will produce an even more negative pleural pressure. Similarly when airways are stiff, an increase in lung volume will cause a more negative Px which will tend to maintain airway patency, reducing the heterogeneity.

Although the shear modulus of the lung has a relatively small effect on the airways under normal conditions the bulk modulus can have an independent influence through its effect on lung volume. The bulk modulus (k) indicates how much the fractional volume changes (ΔV/V) in response to a given change in transpulmonary pressure (ΔPtp); it is defined by k = ΔPtp/(ΔV/V). Thus, the greater the bulk modulus, the smaller the lung volume change for a given change in Ptp. This means that as the lung becomes stiffer, there will be less airway dilation with lung inflation, if the lung is inflated to the same end-inspiratory pressure. If, however, the lung were inflated to the same end-inspiratory volume, then with an elevated bulk modulus, the resultant Ptp will be higher, and this will result in increased airway dilation. These effects of bulk modulus come into play in two situations. The first is in the normal lung, where because of the nonlinearity of the volume- pressure curve, the bulk modulus increases with lung volume (43). The second is in a pathologic lung where there may be an increased bulk modulus even at low lung volume. However, this complex interaction with the bulk modulus has not been fully analyzed, so it is difficult to predict the quantitative magnitude of the effect.

A key question is how important is the contribution of this airway-parenchymal interaction in limiting airway narrowing during bronchoconstriction? Lai-Fook attempted to address this question by measuring airway diameters using tantalum bronchograms. He altered the pressure area relationship of the airways by administering isoproterenol and changed the bulk and shear moduli of the lung by inducing gas trapping (44). The bronchi were modeled as thin-walled elastic tubes contained within cylindrical holes in the lung parenchyma that were assumed (without their contained airways) to change in diameter as the cube root of lung volume (i.e. analogous to the thought experiment described above). These investigators found as expected, that Px was a function of airway caliber and lung volume. Figure 6 shows the results of their experiments. In the presence of tone, Px was slightly more negative than pleural pressure, but this difference increased when the shear modulus of the lung was increased by gas trapping. It is of interest that after bronchodilation the estimated interstitial pressure became slightly more positive than pleural pressure such that the lung parenchyma tended to compress the intraparenchymal airways (case b in Figure 6B). However, the differences between pleural and predicted airway interstitial pressures were quite small under all conditions. with Px in the normal parenchyma being ≈ –1cmH2O, supporting the idea that at FRC this component of parenchymal interdependence provides only a small part of the pressure distending airways and only a very small additional stress against which smooth muscle must act to narrow airways, compared with that provided by transpulmonary pressure alone.

Figure 6.

A. This schematic shows the effect of interaction between the lung parenchyma and airway. In these examples the excised bronchus is illustrated by the solid bold line with diameter De, the uniform hole in the parenchyma into which the airway must fit is shown by the thin solid line (Du), and the actual in situ diameter of the airway is shown by the interrupted line (Di). In case A, the excised bronchus is smaller than the space within the parenchyma so that Px will be negative relative to pleural pressure. In case B, the excised bronchus is larger than the space within the parenchyma so that Px will be positive. Ppl = pleural pressure, Pbr = intra airway pressure and Palv = alveolar pressure.

B. The graphical solution to equation 1 for the normal situation where the excised bronchial diameter (De) is smaller than the uniform space within the parenchyma in which the airway is situated (Du). The relationships between Du and Di and transpulmonary pressure (Ptp), and between De and transmural pressure (Ptm) are plotted. The nonuniform behavior of the parenchymal hole at a constant transpulmonary pressure Ptp’ is given by the line a-b, which is a plot of Δ Du/Du versus ΔPx from Equation 1. Given values for Du and Di (points a and c) at Ptp’, point d on the De-Ptm curve is determined. Alternatively, given the value for Du and De-Ptm behavior (line f-d), the value of Di (point c) is determined. Δ Px is the difference between peribronchial pressure and pleural pressure, and µ = the shear modulus of the parenchyma. From Lai-Fook, et al (44).

Lai-Fook and his colleagues confirmed their estimates of Px by measuring the peribronchial interstitial pressure in excised canine lobes using saline filled wicks implanted in the loose connective tissue of the adventitial space around the large airways (26). They found that the interstitial pressure was −2 cmH2O at a transpulmonary pressure of 2 cmH2O and decreased to −9 cmH2O at transpulmonary pressure of 25 cmH2O. It is also worth noting that interstitial pressure was also influenced by the mean vascular pressure. Decreasing pulmonary artery pressure from 25 to 10 cmH2O resulted in a mean decrease in Px of 1 cmH2O at a Ptp of 2 cmH2O and 2 cmH2O at a Ptp of 25 cmH2O. This interdependence of airways, blood vessels and parenchyma can be explained by the fact that the airways and pulmonary arteries lie immediately adjacent to each other, sharing the same interstitial space. Since Lai-Fook and colleagues could only measure Px around large airways it is not known how deep into the lung this interaction occurs. However, the finding that pulmonary vascular congestion increases peripheral airway resistance in dogs suggests that the vascular-airway interdependence extends to the peripheral lung (61). This interaction is complex, and there is also good evidence that vascular engorgement can physically impinge on the airways, directly compressing them and narrowing their lumen (11).

Both end-expiratory lung volume (5, 20) and tidal volume (72) have a profound effect on the degree of airway narrowing that is induced by bronchoconstricting agonists in humans and experimental animals. The effect of increasing end-expiratory lung volume is related in part to the fact that airways are at larger starting diameter at higher lung volumes. If the degree of smooth muscle shortening is the same at the increased diameter, then this shortening will have a smaller effect on resistance at the higher diameter. This is a direct result of the fact that the airway resistance is inversely related to the 4th power of the diameter. In addition a higher lung volume (and Ptp) will increase the initial circumferential stress in the airway augmenting the load against which the smooth muscle must contract and will influence where the smooth muscle is on its length-tension curve. The increased load and movement away from optimal length for generation of force can both lessen the degree of smooth muscle shortening with the same level of stimulation (59).

Cyclic strain applied to smooth muscle during tidal breathing is also an important mechanism for influencing the degree of airway narrowing. The circumferential strain produced by breathing apparently disrupts actin-myosin bonds and causes myosin depolymerization, attenuating the force that would be produced under static conditions (22, 41, 72). When airway smooth muscle length is oscillated in vitro at an amplitude mimicking the length fluctuation induced by tidal breathing, the force-generating capacity of the muscle is reduced (83).

Thus, lung static and dynamic inflation markedly attenuate the ability of the airway smooth muscle to contract and narrow the airways. These effects result from a combination of the more negative Ppl at high lung volume and the reduced smooth muscle contractility. With smooth muscle contraction there is also an additional load, caused by the distortion of the parenchyma surrounding the airways, and this load increases at higher lung volumes and with greater smooth muscle shortening. The relative magnitude of these loads on airway smooth muscle is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The elastic loads (arbitrary units) impeding airway smooth muscle shortening are plotted against fractional smooth muscle shortening. Data are for a 10th generation bronchus. The line labeled Ptp represents the load contributed by transpulmonary pressure. The influence of transpulmonary pressure decreases as the airway narrows due to the decreasing radius of curvature but ΔPx, which is related to the shear deformation of the parenchyma, increases as smooth muscle shortens. Modified from Lambert et al (46).

The role of hysteresis

Lai-Fook and colleagues did all their experiments with the lung held at various volumes on the deflation limb of the lung’s pressure volume curve but we know the lung shows considerable pressure volume hysteresis, such that after a deep inspiration (DI) to total lung capacity the transpulmonary pressure at is lower and the lung volume is higher than at the starting point. Similarly the airway pressure diameter behaviour can show hysteresis after inflation to a high pressure, with the diameter being larger and the transmural pressure being lower compared to that at the initial point. To the extent that the effect of inflation is different on parenchyma and airways, DIs can influence the relationships between lung volume and airway diameter in situ. In mammalian lungs, hysteresis in the parenchyma’s pressure-volume relationship is primarily related to surface forces acting at the alveolar level. Although as noted earlier, there is good evidence that airway smooth muscle tone can by itself increase parenchymal stiffness (57), the primary effect of tone will be to increase the hysteresis in the airway pressure diameter curve.

A simplified analysis of the effects of variable hysteresis of lung and airways was introduced by Froeb and Mead (24). They measured the effects of lung volume history on dead space volume as an indirect estimate of mean airway calibre. They found that after a DI, dead space volume was larger than at the same lung volume after inflation from residual volume. They reasoned that under these conditions, their observation meant that the hysteresis of the airways was greater than that of the parenchyma. Airway hysteresis in response to stretch is the major determinant of the effect of a DI on airway size and airway smooth muscle tone is the most important source of airway hysteresis (80). Induced bronchoconstriction with contractile agonists substantially increases airway hysteresis such that, during bronchoconstriction a DI can markedly increase airway calibre and maximal expiratory flow in normal subjects. Note that this increased airway size after the DI occurs with little impact from the surrounding parenchyma. That is, although there would be a small increase in pleural pressure (i.e., smaller transpulmonary pressure) caused by parenchymal hysteresis (which would tend to decrease airway size), this is insufficient to counteract the more substantial lengthening of the contracted airway smooth muscle caused by the DI. In addition, after the DI, there would also be an increased lung volume, which would increase the Du in Equation 1, thereby partially compensating for this decrease in airway transmural pressure. In this situation the primary effect of the interdependence is in transmitting the pleural pressure to the airways, and the properties of the airways and smooth muscle tone play the dominant role.

The concept of relative hysteresis was used by Burns et al in an attempt to explain the variable effects of deep inspiration on airway resistance and maximal expiratory flow in asthmatic subjects (12). They made use of the partial flow volume curve (P), which is initiated from end inspiration, as compared to the maximal flow volume curve (M), which is initiated from TLC. By comparing the flows at the same absolute lung volume (typically 30 – 40% of vital capacity), it is possible to determine the effect of the inflation to TLC. The effect of deep inspiration is expressed as the ratio of the flow after the TLC inflation to the flow after the end-inspiratory inflation at the same lung volume (i.e. the M/P ratio). In normal subjects such a manoeuvre causes slight increases in flow at isovolume (i.e., M/P ratio > 1), which means that the airways are dilated by the large inflation, and that they stay enlarged for at least the duration of the forced expiration. The authors interpreted this as being compatible with the airways showing slightly more hysteresis than the parenchyma (84). This effect in normal subjects could be enhanced by administering an inhaled airway smooth muscle agonist such as methacholine. When this was done the flow on the maximal expiratory flow-volume curve was now much greater than that on the partial curve (M/P >>1) indicating an exaggerated effect of the inflation to TLC on the contracted airways. Lim and colleagues, however, found a very different behaviour during spontaneous asthmatic attacks (47). Under these conditions the deep inspiration actually decreased flow at isovolume resulting in a M/P ratio less than 1. This result contrasted sharply with the response to deep inspiration in a group of stable asthmatics in whom bronchoconstriction (of a similar magnitude to that experienced by the spontaneously obstructed group) was induced by inhaled histamine or cold air. In these subjects deep inspiration produced considerable bronchodilation with a M/P ratio substantially greater than 1, similar to what was seen in non-asthmatics. The authors argued that these results could be explained by differences in the relative hysteresis of airways and parenchyma and they attributed this to different mechanisms of airway narrowing during spontaneous versus induced bronchoconstriction. However, as discussed below, this result has less to do with relative hysteresis and is more likely is a reflection of different properties of the airway smooth muscle when activated during an asthmatic episode.

Airway hysteresis is principally related to a reduction in ASM force caused by the stress induced by a deep inspiration. The non-contractile elements of the airway wall show very little hysteresis. To the extent that the increased transmural pressure during a DI is borne by noncontractile elements in the airway, such as the connective tissue in the adventitia and subepithelial layers, there will be less airway hysteresis, and airways may dilate less, or not at all, following a DI. Similarly, if there is substantial occlusion of airways by mucus plugs or if ASM tone results in a stiffer airway because of increased ASM mass or enhanced contractile function, airways will show less hysteresis in response to the decrease in Ppl (22, 65). However even if there were no airway hysteresis, it is difficult to imagine that the relatively small decrease in Ppl which occurs on return to FRC (because of parenchymal hysteresis) is sufficient to explain the magnitude of the paradoxical airway narrowing in response to DI that occurs in some asthmatics. This would be even more unlikely if after the DI, there was a return to the same FRC and Ppl. The more likely possibility is that the strain produced by deep inspiration causes contraction of airway smooth muscle during spontaneous attacks or periods of uncontrolled asthma. Marthan and Woolcock suggested such a stretch-induced contraction (a myogenic response) as a potential mechanism and showed that the effect was attenuated by administering a calcium channel blocker (53). This concept, that airway smooth muscle may be activated by a DI, was supported by the results of an imaging study by Brown et al. (10). These investigators showed that there was comparable airway dilatation (measured at TLC by computed tomography) following a DI in normal and mildly asthmatic subjects. However, on return to FRC the airways of the asthmatics narrowed, whereas those of the normal subjects remained dilated, suggesting that some active process such as stretch-induced contraction (53) may have contributed to the paradoxical response.

Mechanically induced bronchoprotection

Airway-parenchymal interdependence may contribute to the phenomenon known as bronchoprotection. Bronchoprotection is the phenomenon by which one or a series of deep inspirations taken before adminstration of a bronchoconstricting agent attenuates the response to that bronchoconstriction stimulus. Refraining from taking regular DI increases airway responsiveness in normal and asthmatic subjects (39, 40, 75) when the response is measured by a fall in FEV1. Avoiding deep inspirations increases the maximal response to methacholine without altering sensitivity in non-asthmatics (16) The bronchoprotective effect of deep inspiration is lost even in people who have mild asthma. It is also attenuated in obese subjects, which could be related to decreased lung volumes (6).The mechanism of this bronchoprotection is not completely understood but one possible explanation is through its effect on on the plasticity (also termed adaptability) of ASM. Airway smooth muscle becomes stiffer if not subjected to periodic strain (22), and its contractile capacity is temporarily lessened after an acute length change as occurs during DI (29)..

Interestingly the bronchoprotection of DI attenuates the decline in FEV1, but does not affect the increase in airway resistance, following bronchprovocation. In one study, the increase in airway resistance caused by inhaled methacholine was the same whether or not deep inspirations preceded the inhalation challenge, but the decrease in FEV1 was significantly less after the DI’s (15). One possibility to explain this finding is that prior DI may not alter the initial airway narrowing produced by a constrictor but instead makes the airway tree more responsive to a subsequent DI as is required to perform an FEV1 maneuver.

Interdependence in pathologic situations

i. Smooth muscle contraction and asthma

Lung parenchymal-airway interdependence has pathophysiological relevance in a number of conditions. Physiological or pathological states that lower resting lung volume are examples. If Ppl is less negative at the lower lung volume, airway calibre will also be decreased, as will the parenchymal shear modulus. This will accentuate the ability of airway smooth muscle to cause airway narrowing and increase airway resistance.

The effect of lung volume on the response to a bronchoconsticting stimulus is mediated by 3 factors: changes in airway smooth muscle length; changes in lung parenchymal shear modulus; and changes in the transmural pressure against which ASM must operate. As the lung is inflated the smooth muscle may be stretched beyond its optimal length for generating force, and the shear modulus of the lung increases along with the transmural pressure. All of these factors contribute to reduced shortening and airway narrowing at higher lung volume. Lambert et al quantified the relative contributions of these in a model of airway narrowing (46) and Oliver et al (65) refined the model to incorporate the effects on smooth muscle of the cyclical stress of tidal breathing and the episodic stress of deep inspirations.

Although the forces of interdependence tend to minimize heterogeneity, they are unable to maintain airway patency when the ASM is strongly stimulated at moderate or low transpulmonary pressure. Gunst and coworkers showed that there was airway closure in intact canine lobes held at a Ptp below 10 cmH2O when ASM was stimulated with high concentrations of methacholine (28). That such airway closure could occur in intact dogs even in large cartilagenous airways was clearly shown by Brown and Mitzner (9). With a system to directly stimulate local airways with histamine in vivo, they used CT imaging to show that at high local stimulation the airway lumen could be made to disappear from the CT scans. In addition, such large airway closure in vivo could occur even at higher levels of lung inflation (7), similar to what was found in excised lungs (28). However, if the lungs are inflated to levels much above 10 cmH2O, then both theory and experiment indicates that interdependence forces could prevent airway collapse (28). The fact that airways adjacent to completely closed airways were shown to be unaffected by such localized intense smooth muscle shortening in vivo is consistent with a very small parenchymal shear modulus. This fact is further supported by results from more invasive measurements that showed that parenchymal distortion surrounding contracted airways did not project very far from the airway wall (1, 67). These observations, and corroborative studies by others (63, 64), have supported the concept that the loads on the ASM provided by parenchymal recoil are insufficient to explain the limitations of ASM shortening which are often observed with in vivo dose-response curves (20, 58, 87). There are several potential reasons for this plateau in the in vivo dose-response curves, but since they are mainly related to smooth muscle properties, with parenchymal interdependence playing a minor role, further discussion of this important observation is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

ii. Role of resting lung volume during sleep

FRC decreases when one assumes the supine posture (3). Ballard et al measured this volume change and the effect of the decrease in lung volume on pulmonary resistance in asthmatic and non-asthmatic subjects. The subjects were studied in a whole body plethysmograph with an esophageal balloon in place to estimate pleural pressure. FRC decreased ~20% in non-asthmatic and ~30% in asthmatic subjects during rapid eye movement sleep. Pulmonary resistance increased commensurate with the reduction in lung volume, but in the asthmatic subjects, who were chosen because they experienced nocturnal symptoms, the increase in resistance was greater than could be accounted for by the reduction in lung volume (i.e., specific conductance decreased). They suggested that in addition to the airway narrowing attributable to decreased lung recoil pressure and volume, active bronchoconstriction occurred. This conjecture was supported by the results of a subsequent study in which they showed that prevention of the decrease in lung volume during sleep by application of continuous negative pressure around the thorax while the subjects slept did not abolish the nocturnal airway narrowing (54). This strongly supports the notion that something is actively increasing smooth muscle tone in these patients. In a third study this group directly tested airway-parenchymal interdependence at higher lung volumes during sleep by measuring pulmonary resistance while they changed lung volume with the application of negative pressure outside the thorax via a cuirass (34). They measured pulmonary resistance and its response to lung inflation prior to sleep and after short and more prolonged periods of sleep. Lung inflation in the recumbent posture had a bronchodilating effect in the asthmatic subjects, but the effect was less than in non-asthmatic subjects. Moreover, after a period of sleep, pulmonary resistance increased further and the bronchodilating effect of lung inflation decreased.

The authors of this work proposed that in asthmatics the airways become “uncoupled” from the parenchyma. This could theoretically occur if there were a substantial leakage or redistribution of interstitial fluid in the lung with an accumulation in the adventitial interstitial space. Such a redistribution could occur because of increased permeability in the bronchial microvasculature in the inflamed airways. Edema in this location would increase Px and thereby reduce the airway transmural pressure. While this effect would exaggerate the effect of the decrease in lung volume that occurs when assuming the recumbent posture as well as attenuating the effect of increase in lung volume, it seems unlikely that the amount of edematous fluid needed for such an observed change in airway function could be so easily mobilized and removed. A more likely explanation for reduced effect of lung volume on airways in this situation is that there is active nocturnal contraction of the airway smooth muscle during sleep with an adaptation of the muscle to the shorter length. The distensibility of asthmatic airways is known to be much reduced during an asthmatic attack (18). Mechanistically this reduced distensibility could involve the formation of latch bridging in asthmatic airway smooth muscle as proposed by Fredberg’s lab (23, 65)

iii. Obesity

Obesity is another condition that can have an effect on airway calibre and responsiveness by changing resting lung volume. Obesity produces marked decreases in FRC and more modest reductions in TLC (36). Obese individuals also breathe with a lower tidal volume (71). The reduced fluctuating strain on the airway smooth muscle caused by the lower tidal volume means that the airways will be stiffer. This effect coupled with the reduction in FRC and TLC may account for the reduced bronchoprotective effect of deep inspiration in obese individuals (6). That is, if the airways are not dilated during the lung inflation, the smooth muscle will not be stretched sufficiently to protect against shortening with further stimulation. The effects of obesity on lung volumes and breathing pattern likely contribute to the airway hyperresponsiveness seen in obesity (73). As mentioned above, breathing at low lung volume increases airway responsiveness in normal individuals (20) and could contribute to the airway hyperresponsiveness in obese individuals. Torchio et al found linear relationships between body mass index and measures of airway sensitivity (PD50) and maximal response to inhaled methacholine; more obese individuals required a lower dose to produce the airway narrowing and their maximal achievable airway narrowing was greater (77). This issue, however, is still unsettled, as evidenced by a recent study from Salome et al, who found no difference in airway sensitivity or maximal response in a direct comparison of obese and non-obese normal subjects (69).

iv. emphysema

Since emphysema leads to loss of lung recoil pressure and of lung stiffness at any lung volume, it results in a less negative pleural pressure (and airway transmural pressure) at any lung volume and is associated with airway narrowing and increased airway resistance (irrespective of any structural narrowing of the airways themselves. The increased resistance can be partly overcome by breathing at a higher lung volume, which increases parenchymal tissue distension and thereby restores lost recoil pressure and thus airway caliber.

This hyperinflation (increased FRC) is a characteristic feature of emphysema and although this application of interdependence serves as an effective compensatory mechanism, it not only requires additional energy, but it also alters the length of the inspiratory muscles and the configuration of the chest wall making the muscles less efficient for their job of expanding the lung.

Many authors suggest that emphysema also alters airway calibre and airway stability by causing a decreased number of direct alveolar attachments connected to the adventitial border of the airway, a process referred to as a loss of airway tethering. While conceptually attractive, this concept is a bit mechanistically misleading. Such a tethering argument requires that these lost attachments will make Px more positive relative to pleural pressure at any given pleural pressure. However, while such localized destruction is possible, and has been quantified, it is not necessary to explain the effect of emphysema on airway calibre. Parenchymal destruction even far from the airway will decrease Ppl, and this loss of lung elastic recoil will by itself decrease airway size. The damage only needs to be sufficient to cause a loss of parenchymal recoil, a fact supported by data showing that the relationship between airway resistance and elastic recoil is similar in normal and emphysematous subjects (18) (i.e., resistance is higher because recoil at any lung volume is lower, but the slope of the resistance versus recoil plot is similar). This fact is also supported by observations following lung volume reduction surgery as a treatment for emphysema. The procedure is often successful even if the most pathologic regions are not excised, as long as the lung recoil is increased after the surgery (25, 31). Along these lines, a recent lung transplant study by Eberlein et al clearly shows that if a lung is transplanted into a thorax that is too small, this will lead to low elastic recoil, smaller airways and poorer long term clinical outcome (21).

This ubiquitous concept of tethering warrants additional consideration. Consider the following thought experiment. In Figure 1, imagine cutting every other alveolar wall that is immediately adjacent and perpendicular to the visceral pleura. Although this would reduce by half the number of walls directly tethering the visceral pleura, it would little effect on the pleural pressure. This is because the number of cut walls would be such a small fraction of the total number of alveolar walls. Now consider cutting half of the walls perpendicular to airways. Again there would be little change in the pleural pressure, because the lung recoil would hardly change. The effect on the airway, however, is more complex than at the pleural surface, since although the lung recoil will not change much by cutting the direct airway tethers, there will be some local effect on the airway. This can occur since the shear modulus of the parenchyma is so small that there can be parenchymal distortions over relatively restricted regions. But the bottom line is that unless there is a large local loss of direct attachments or a significant loss of lung elastic recoil, there will likely be only a small effect on the airways. This critical aspect of elastic recoil will also impact maximal expiratory flow, since the recoil pressure is the driving pressure for maximal expiratory flow (56, 76). The more pronounced expiratory airway compression that occurs in subjects with emphysema is primarily due to both this reduced driving pressure and an increased peripheral airway resistance, rather than to a loss of alveolar tethers immediately adjacent to the airways.

It is often suggested that the loss of direct physical attachments to the airway makes the airways more prone to collapse during expiration in emphysema. This concept is supported by the observation that expiratory airflow limitation and central airway collapse can occur even during quiet breathing in subjects who have advanced emphysema. However, flow limitation and central airway collapse are profoundly influenced by peripheral airway resistance and lung elastic recoil. Hogg and associates found that the marked increase in small airway resistance in emphysematous lungs could not be corrected by increasing lung volume to re-establish lung recoil (30). They suggested that it was predominantly the increased peripheral airway resistance that leads to the increased likelihood of airway collapse in the more central airways on expiration. This would occur not because Px is more positive during expiration, but because luminal airway pressure is less positive. If Px were more positive, then expiratory resistance would be greater than inspiratory resistance, upstream of the flow-limiting segment. However, this was not found by Hogg, et al (30), who showed that, even in lungs with advanced emphysema and markedly increased airway resistance, there was no difference in peripheral resistance when measured in inspiration or expiration. Although this interpretation seems logical, as with many situations in complex human diseases, there are alternative data and explanations. For example, as noted above, Colebatch et al found that the increase in airway calibre with lung inflation was the same in normal and emphysematous subjects (18). This difference from Hogg et al may reflect a different subject population (e.g., Hogg, et al studied COPD patients, not just those with an emphysematous COPD phenotype) or different parts of the airway tree (i.e., large vs. small), but at the present time it’s not possible to resolve these interpretations.

Lastly, we note that measurements of Raw in humans with emphysema generally show an increase (13, 19, 30), indicating that the decreased size of the peripheral airways is detectable when measuring resistance of the whole tree. This increased airway resistance in emphysema, however, is only partially supported by results in animal models, since a number of studies not only show no increase, but in fact sometimes even show a decrease in resistance (35, 60, 78). Explanations for such a decrease in these animal models are unclear, but if true could reflect a structural change that leads to enlarged airways.

Axial and Parallel Heterogeneity

As the previous sections have emphasized, the forces of interdependence are important in minimizing heterogeneity of airway resistance and ventilation within the lung. The resistance of the tracheobronchial tree is a reflection of the combined resistances of all generations of airway arranged in series and parallel. The increasing number of parallel pathways as one moves peripherally in the lung increases the possibility of heterogeneity in resistance, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, and resultant gas exchange impairment. Although interdependence of airways and parenchyma provides homogenizing forces, this mechanism is not perfect, and spatial heterogeneity in resistance does develop in disease and can have profound affects, not only on airway resistance, but also on gas exchange. Bates attempted to quantify the consequences of heterogeneity in airway dimensions for airway resistance using Monte Carlo simulation to assign airway parameters according to a probability distribution function with anatomically reasonable mean values but progressively larger standard deviations (4). His results show that the simple presence of such statistical heterogeneity can cause an increase in airway resistance. In addition, such statistical heterogeneity coupled with heterogeneity of ASM shortening can produce airway hyperresponsiveness. That is, the same average airway narrowing can have a greater and more variable effect when there is a larger variability in the narrowing. This amplifying effect of heterogeneity is related to the nonlinear relationship between airway radius and resistance. Simply put, the higher resistance of the narrower airways in the distribution is not compensated for by the less constricted airways. These predictions have been confirmed with more sophisticated modeling and the additional insight that a critical feature of spatial heterogeneity is the development of a population of completely (or nearly completely) closed peripheral airways (2, 48). The consequences of these observations are profound, since any factor that contributes to heterogeneity can increase resistance and amplify the effect of contractile stimuli.

Accumulating evidence indicates that there is both axial and parallel heterogeneity in airway structure and function and that this heterogeneity is increased in disease states. Axial heterogeneity initially received much attention when it became clear that the serial distribution of resistance was heterogeneous. The pioneering work by Macklem & Mead (49) in dogs confirmed the earlier calculations of Green, based on laminar flow in the Weibel dichotomous branching model, which showed that airways less than 2 mm in diameter accounted for less than 10% of the total resistance (27). Hogg, et al showed similar results in normal human lungs, with a marked increase in peripheral resistance in diseased lungs (30). Less attention has been paid to the consequences of the development of an isolated narrowing or bottleneck at a single point in an airway. Such axial heterogeneity is particularly insidious because a much narrower point along the length of a pathway will increase the resistance of that entire pathway substantially. The decreased flow caused by such a bottleneck can influence parenchymal-airway interdependence downstream of that point and can amplify its effect. An example of the rectifying force of interdependence is the protective effect of generalized, as opposed to localized, bronchonconstriction. As mentioned above, Brown and Mitzner administered histamine to dogs via aerosol or by direct instillation to individual bronchi (9). Direct instillation was capable of causing complete airway closure while much higher concentrations of aerosolized methacholine failed to cause airway closure in the same airways. Although the authors suggested that the aerosol method might not deliver sufficient agonist to the airway, an alternate explanation is that the uniform contraction of all airway smooth muscle stabilized the airway by stiffening the lung. One remarkable observation from this study relates to the concept of axial interdependence. This addresses the question of whether there is sufficient tension in the structural fibers that run axially in the airway wall to affect local narrowing. The results from this study clearly indicate that individual airway segments behave as though they were completely isolated from other segments along the axis. Figure 8 shows that airway segments just a few mm on either side of a region that contracted to closure, remains wide open. This result suggests that at FRC, there is relatively little elastic tension in the axial fibers, but how much this might changes with increases in lung volume and transpulmonary pressure is not known.

Figure 8.

Result showing the relative independence of airway narrowing along the axis of an airway. A 12 mm diameter airway was stimulated locally with 1, 10, and 100 mg/mL histamine, and the resultant size was measured with high resolution CT. With the highest histamine dose, the airway was completely closed, but the closure was localized to a very short region. Less than 1 cm along the axis, the airway is almost fully open. The coin is shown for scale perspective. Figure is adapted from data in reference (9).

The increased sophistication of techniques for lung imaging has allowed direct measurement of the variability of airway dimensions and narrowing in human lungs (37). Radioisotope (38, 62) and MRI techniques (17, 70) have shown the development of relatively large ventilation defects in asthmatic subjects during spontaneous or induced bronchoconstriction. These defects support the presence of heterogeneous airway narrowing and their relatively large size suggest that airway closure of large airways may be responsible. However, the elegant modeling studies of Venegas et al. suggest that the large defects may actually be a manifestation of clustering of constricted peripheral airways (79). This work also confirmed the presence of large ventilation defects in bronchoconstricted asthmatics using PET scanning. Although the ventilation defects were large and conformed to bronchopulmonary segments or lobes, they were not homogeneous, and ventilation of units within the low ventilation regions showed a bimodal distrubution, with some small units receiving normal levels of ventilation. The authors reasoned that this distrubution could not have been brought about by central airway closure but rather by clustering of more peripheral airway closure. The model developed by this group to interpret their results relied on the interplay between airway-parenchymal interdependence, airway transmural pressures, and smooth muscle contraction (86). This analysis was based on the model of Anafi and Wilson (2), which proposes that as an airway narrows, the volume of air entering the parenchymal unit subtended by that airway decreases, and the unit’s end-inspiratory volume decreases leading to a lessoning of the parenchymal tethering in the airways within the unit. This in turn further reduces the underventilated unit’s ventilation and volume leading to a viscious cycle that leads to airway closure. However for tidal volume to remain constant, parallel units must receive more ventilation, increasing their volume which results in a dilation of the airways supplying them. This divergent behavior leads to heterogeneity, and it is airway parenchymal interdependence that initiates the heterogeneity. While this seems intuitively plausible, there are some issues with this interpretation. A slight narrowing of a large airway would have little effect on the local volume and pleural pressure at the end of inspiration, since with no flow the distribution of volume depends on local compliances. However with very severe airway narrowing the time constant of lung units, rather than their compliance, determines their ventilation, and in the analysis of Venegas et al (79) the catastropic clustering only occurred above a critical level of airway constriction. On the other hand, severe airway narrowing might be expected to lead to progressive gas trapping and hyperinflation in the downstream units, which would tend to dilate all of the more peripheral airways, thereby lessening heterogenetiy. It remains possible that the heterogeneity of airway narrowing in diseased lungs is not related to the forces of interdependence but is rather due to a nonhomogeneous distribution of the constricting stimuli accompanied by structural heterogeneity in airway smooth muscle or airway remodeling.

Conclusion

In this review, we considered how the airways are affected by their location within the lung parenchyma and to a lesser extent discussed how the mechanical properties of the airways affect the lung. The mechanics of this physical interaction has important manifestations in normal and pathologic situations. This interaction is commonly referred to as “interdependence,” and we have used this descriptive term in the title of the manuscript. The airway tree and the lung parenchyma have independent physical properties that are difficult to study in isolation; it is the interdependence between them that determine the behavior of the whole lung. Thus airway-parenchymal interdependence reflects an intrinsic property of the lung. The lynchpin of this interdependence is the elastic recoil pressure of the lung, which creates an effective airway transmural pressure that dilates the airways as transpulmonary pressure and lung volume increase. The common concept of airway tethering, which suggests that airways are pulled open by virtue of the direct attachments of alveolar walls to an airway is a somewhat misleading model, since the density of local alveolar attachments to an airway by itself is unlikely to play the major role. Continuum mechanics analysis of the lung parenchyma allows the prediction of the pressure outside the airway, but in most situations this pressure is very close to the pleural pressure.

Airway-parenchymal interdependence has substantial physiological and pathophysiological significance. Normal airway caliber is maintained by this mechanism, and it serves to resist airway compression during forced expiration as well as the ability of airway smooth muscle to narrow airways. Weakening of the rectifying forces of interdependence contributes to airway dysfunction and gas exchange impairment in acute and chronic airway diseases including asthma and emphysema.

Contributor Information

Peter D Paré, University of British Columbia.

Wayne Mitzner, Johns Hopkins University.

References

- 1.Adler A, Cowley EA, Bates JH, Eidelman DH. Airway-parenchymal interdependence after airway contraction in rat lung explants. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:231–237. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anafi RC, Wilson TA. Airway stability and heterogeneity in the constricted lung. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1185–1192. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballard RD, Irvin CG, Martin RJ, Pak J, Pandey R, White DP. Influence of sleep on lung volume in asthmatic patients and normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:2034–2041. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.5.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates JH. Stochastic model of the pulmonary airway tree and its implications for bronchial responsiveness. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:2493–2499. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates JH, Schuessler TF, Dolman C, Eidelman DH. Temporal dynamics of acute isovolume bronchoconstriction in the rat. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:55–62. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulet LP, Turcotte H, Boulet G, Simard B, Robichaud P. Deep inspiration avoidance and airway response to methacholine: Influence of body mass index. Can Respir J. 2005;12:371–376. doi: 10.1155/2005/517548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown RH, Mitzner W. Airway closure with high PEEP in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:956–960. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown RH, Mitzner W. Effect of lung inflation and airway muscle tone on airway diameter in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;80:1581–1588. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.5.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown RH, Mitzner W. The myth of maximal airway responsiveness in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1998;85:2012–2017. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RH, Scichilone N, Mudge B, Diemer FB, Permutt S, Togias A. High-resolution computed tomographic evaluation of airway distensibility and the effects of lung inflation on airway caliber in healthy subjects and individuals with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:994–1001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.2007119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RH, Zerhouni EA, Mitzner W. Visualization of airway obstruction in vivo during lung vascular engorgement and edema. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1995;78:1070–1078. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.3.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns CB, Taylor WR, Ingram RH., Jr Effects of deep inhalation in asthma: relative airway and parenchymal hysteresis. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1985;59:1590–1596. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler J, Caro CG, Alcala R, Dubois AB. Physiological factors affecting airway resistance in normal subjects and in patients with obstructive respiratory disease. J Clin Invest. 1960;39:584–591. doi: 10.1172/JCI104071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caro CG, Butler J, Dubois AB. Some effects of restriction of chest cage expansion on pulmonary function in man: an experimental study. J Clin Invest. 1960;39:573–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI104070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman DG, Berend N, King GG, McParland BE, Salome CM. Deep inspirations protect against airway closure in nonasthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:564–569. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00202.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman DG, King GG, Berend N, Diba C, Salome CM. Avoiding deep inspirations increases the maximal response to methacholine without altering sensitivity in non-asthmatics. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;173:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen BT, Johnson GA. Dynamic lung morphology of methacholine-induced heterogeneous bronchoconstriction. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1080–1086. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colebatch HJ, Finucane KE, Smith MM. Pulmonary conductance and elastic recoil relationships in asthma and emphysema. J Appl Physiol. 1973;34:143–153. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.34.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayman H. Mechanics of airflow in health and in emphysema. J Clin Invest. 1951;30:1175–1190. doi: 10.1172/JCI102537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding DJ, Martin JG, Macklem PT. Effects of lung volume on maximal methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in normal humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1987;62:1324–1330. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.3.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eberlein M, Permutt S, Brown RH, Brooker A, Chahla MF, Bolukbas S, Nathan SD, Pearse DB, Orens JB, Brower RG. Supranormal expiratory airflow after bilateral lung transplantation is associated with improved survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:79–87. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0593OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fredberg JJ, Inouye D, Miller B, Nathan M, Jafari S, Raboudi S, Butler JP, Shore SA. Airway smooth muscle, tidal stretches and dynamically-determined contractile states. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;156:1752–1759. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9611016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredberg JJ, Jones KA, Raboudi NS, Prakash YS, Shore SA, Butler JP, Sieck GC. Friction in airway smooth muscle: mechanism, latch, and implications in asthma. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;81:2703–2712. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Froeb HF, Mead J. Relative hysteresis of the dead space and lung in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1968;25:244–248. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelb AF, McKenna RJ, Jr, Brenner M, Fischel R, Baydur A, Zamel N. Contribution of lung and chest wall mechanics following emphysema resection. Chest. 1996;110:11–17. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goshy M, Lai-Fook SJ, Hyatt RE. Perivascular pressure measurements by wick-catheter technique in isolated dog lobes. J Appl Physiol. 1979;46:950–955. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.46.5.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green M. How big are the bronchioles? St Thomas Hospital gazette. 1965;63:136–139. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunst SJ, Warner DO, Wilson TA, Hyatt RE. Parenchymal interdependence and airway response to methacholine in excised dog lobes. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1988;65:2490–2497. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.6.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrera AM, McParland BE, Bienkowska A, Tait R, Pare PD, Seow CY. 'Sarcomeres' of smooth muscle: functional characteristics and ultrastructural evidence. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2381–2392. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM. Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196806202782501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoppin FG., Jr Theoretical basis for improvement following reduction pneumoplasty in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:520–525. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell JB, Permutt S, Proctor DF, Riley RL. Effect of inflation of the lung on different parts of pulmonary vascular bed. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:71–76. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyatt RE, Flath RE. Influence of lung parenchyma on pressure-diameter behavior of dog bronchi. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1966;21:1448–1452. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.5.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irvin CG, Pak J, Martin RJ. Airway-parenchyma uncoupling in nocturnal asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:50–56. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9804053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito S, Ingenito EP, Brewer KK, Black LD, Parameswaran H, Lutchen KR, Suki B. Mechanics, nonlinearity, and failure strength of lung tissue in a mouse model of emphysema: possible role of collagen remodeling. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:503–511. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00590.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones RL, Nzekwu MM. The effects of body mass index on lung volumes. Chest. 2006;130:827–833. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King GG, Carroll JD, Muller NL, Whittall KP, Gao M, Nakano Y, Pare PD. Heterogeneity of narrowing in normal and asthmatic airways measured by HRCT. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:211–218. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00047503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King GG, Eberl S, Salome CM, Young IH, Woolcock AJ. Differences in airway closure between normal and asthmatic subjects measured with single-photon emission computed tomography and technegas. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1900–1906. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9608027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]