Abstract

Purpose

Functions of antimicrobial peptidoglycan recognition proteins (Pglyrp1-4) at the ocular surface are poorly understood. Earlier, we reported an antibacterial role for Pglyrp-1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Here we investigated functions of three other related genes Pglyrp-2, -3 and -4 in a mouse model of P. aeruginosa keratitis.

Methods

Wild type (WT) and each of the Pglyrp-null genotypes were challenged with P. aeruginosa keratitis. The eyes were scored in a blinded manner 24 and 48h post infection. Viable bacterial counts and inflammatory factors (IL-12, TNF-α, IFN-γ, CCL2, IL-6 and IL-10) were measured in whole eye homogenates using cytometric bead arrays. Expressions of Pglyrp-1-4, mouse beta defensins (mBD)-2,-3, cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) were determined by qRTPCR in total RNA extracts of uninfected and infected eyes of WT and each of the Pglyrp-null mouse types.

Results

The Pglyrp-2 -/- mice showed reduced disease and lower induction of pro-inflammatory TNF-α (p = 0.02) than WT or the other Pglyrp null mice. Viable bacterial yield was significantly lower in the Pglyrp-2-/- (p = 0.0007) and the Pglyrp-4-/- (p = 0.098) mice. With regards to expression of these antimicrobial genes, Pglyrp-2 expression was induced after infection in WT mice. Pglyrp-3 expression was low before and after infection in WT mice, while Pglyrp-4 expression was slightly elevated after infection in WT, Pglyrp-2 and -3 null mice. Pglyrp-1 expression was slightly elevated after infection in all genotypes without statistical significance. Transcripts for antimicrobial peptides mBD2, mBD3 and CRAMP were elevated in infected Pglyrp-2 -/- males without statistical significance.

Conclusions

Efficient resolution of keratitis in the Pglyrp-2 -/- mice may be due to a reduced pro-inflammatory microenvironment and synergistic antibacterial activities of defensins, CRAMP and Pglyrp-1. Therefore, in ocular infections the pro-inflammatory functions of Pglyrp-2 must be regulated to benefit the host.

Introduction

The peptidoglycan recognition proteins (Pglyrps) are conserved from insects to humans [1]. In insects this is a family of 19 proteins while in mammals there are only four genes that encode four secreted proteins [2, 3]. Human PGLYRP-1 is the smallest (196 aa), while PGLYRP-2 (576 aa), -3 (341 aa) and -4 (373 aa) are larger. PGLYRP-3 and -4 can form homodimers and heterodimers. All four mammalian members are antibacterial, have at least one Pglyrp domain in the C-terminal that shares homologies with bacterial type 2 amidases. In addition, all recognize gram-positive bacterial peptidoglycans, [4] but can also interact with gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharides and fungal cell wall components [3]. Mammalian Pglyrp-2 is the only remaining member with an n-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase activity that hydrolyzes peptidoglycans. Mice deficient in Pglyrp-1 have normal survival and body weight, but show increased susceptibility to intraperitoneal injections of Bacillus subtilis [5]. Pglyrp-1 is a major component of polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) and eosinophil granules and Pglyrp-1-/- mice PMN show normal bacterial uptake but poor bacterial clearance [5]. The Pglyrps also interact with cell surface pathogen recognition receptors such as the toll-like receptors and cytoplasmic Nod 1 [6, 7], thereby regulating the microbial population and the host inflammatory milieu. In a gene expression study of the cornea compared to tendon and the lens, we detected increased expression of Pglyrp-1 in the cornea [8]. In a follow-up study we found constitutively high expression of Pglyrp-1 in the superficial cells of the corneal epithelium in mouse and human corneas, and Pglyrp-1 -/- mice challenged with P. aeruginosa keratitis showed poor bacterial clearance and resolution of keratitis [9]. These findings suggested a protective role for Pglyrp-1 at the ocular surface while functions of the other members, Pglyrp-2-4, at the ocular surface are largely unknown. Pglyrp-2 is expressed at high levels in the liver and the protein is secreted into the blood; in cultured epidermal and corneal keratinocytes, it was inducible by peptidoglycans [10, 11] Pglyrp-3 and -4 are widely present in various mucosal surfaces and in cultured corneal epithelial cells [7]. To investigate functions of Pglyrp-2-4 in ocular defense mechanisms, we investigated the response of gene-targeted mice deficient in Pglyrp-2, -3 and -4 to ocular infections with P. aeruginosa. Our study shows that disease severity is reduced with improved bacterial clearance in Pglyrp-2-/- mice that may be due to compensatory over expression of defensins (mBD2 and 3), cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptides (Cnlp) and Pglyrp-1.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Dr. Roman Dziarski (Department of Microbiology & Immunology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indiana, USA) kindly provided mice deficient in Pglyrp-2, Pglyrp-3 and Pglyrp-4 genes in the BALB/c background. Wild-type BALB/c (WT) mice were purchased from Charles River (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) and a colony was maintained in our facility for this study. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility of the Johns Hopkins University. The institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Johns Hopkins University specifically approved this study. Eight-ten week old male and female mice were used for these experiments. All experiments using mice were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa Keratitis

The P.aeruginosa ATCC 19660 strain grown on cetrimide agar plates and ~ 0.5 x 108 CFU/ml was used for corneal infections [12]. Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of avertin (2,2,2-Tribromoethanol) and an inoculum of 5μl of the bacterial suspension was applied with a 26 gauge needle on one scarified cornea per animal as described previously [13]. The mice were examined in a blinded manner under a dissecting microscope (SMZ 1500; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a digital camera (DXM 1200; Nikon), and given a disease score based on a published scoring matrix [14]: 1- faint partial opacity, 2- dense opacity covering the pupil, 3- dense opacity over the entire eye, 4- corneal perforation and or phthisis bulbi. Clinical scores were obtained on all animals, while subsets were used for bacterial yield, cytokine analyses or histology. We used 5 different strains of mice with 4–5 independent experiments per strain, using 6–8 animals per experiment. This required extensive breeding, over a long period of time to generate a large number of animals to obtain age and gender matched mice for each experiment, and the experiments were carried out in batches over a period ~6 months. We included a set of WT control animals with each days experiment. Infected and un-infected eyes were photographed and selected representative eyes are shown. Viable bacterial yield was calculated by plating serial dilutions of whole eye homogenates in PBS from mice euthanized 2 days after infection.

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRTPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from 6 animals per genotype from uninfected and 48 hour infected whole eyes in 500 μl of TRIzol (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 100ng of total RNA with reverse transcriptase (Superscript II; Invitrogen Corp.) and oligo (dT) primers and stored at −20°C until use. Real time qRTPCR was carried out using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and the sequence detection system ABI PRISM 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All primers used are shown in Table 1. The following PCR conditions were used for Pglyrp-1-4. The ramp rate was 1.6°C/sec; hold stage 1 was 50°C for 2 minutes and 95°C for 5 minutes; PCR stage at 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min; hold Stage 2 was at 72°C for 5 min; melt curve stage was at 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min, 95°C for 15 sec. Expression relative to Gapdh (2-ΔΔCT) was calculated where ΔΔCT = (Ct gene-Ctgapdh) infected eye−(Ct gene-Ctgapdh) uninfected eye.

Table 1. Primers used in qRTPCR experiments.

| Gene | Forward primer (5'-3') | Reverse primer (5'-3') |

|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | CCCTGGCCAAGGTCATCC | TGATGGCATGGACTGTGGTC |

| Pglyrp1 | GCAATGTGCAGCATTACCAC | CTGTGTGGTCACCCTTGATG |

| Pglyrp2 | TAGGCTCCGACGGCTATCTG | GTTCAGCGCAGCTTCGTT |

| Pglyrp3 | GGCCTGTGGCAACCCAACCA | AGGGTACGGGCAGGCTCAGT |

| Pglyrp4 | ACATCCAGCCATTGCTTGCGAA | CCGTGGAACTATGTGGGGACAAGC |

| Hprt1 | CAGACTGAAGAGCTACTGTAATGA | CTTTCCAGTTAAAGTTGAGAGATCA |

| Cramp | TGAAGGCACATTGCTCAGGT | CCCAAGTCTGTGAGGTTCCG |

| Mdb2 | CGAAAATCAGGGCTCAGTGC | TTCCCAGGTATCTTGCCAGC |

| Mdb3 | CAGGCCCTTGGGCAAGTC | AGCTAAGTGGATTGAGTGCCT |

For the three antimicrobial peptides, mouse beta-defensin 2 (mBD2), mouse beta-defensin 3 (mBD3) and cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide Cnlp-encoded CRAMP, 250 ng of total RNA was used to generate cDNA at 50°C for 60 min using iScript™ Reverse transcription Supermix (BIO-RAD). Samples containing no reverse transcriptase or water in place of RNA (no template control) served as negative controls. PCR amplification of cDNA was performed with SsoAdvanced™SYBR Green Supermix (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA) using PrimePCR™SYBR Green specific primers for mBD2, mBD3, CRAMP, and HPRT (see Table 1). The following PCR conditions were used 95°C for 2 minutes (activation), and 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds (denaturation, annealing/extension) using a CFX96™ Real-Time System (BIO-RAD). For each gene, the samples from six animals were processed in triplicate and relative fold change (2-ΔΔCT) was calculated with respect to Hprt1.

H&E staining section

Eyes were enucleated and placed in 10% formalin/PBS, 5-mm corneal sections were prepared, and H & E staining was performed by the pathology core facility at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions (Reference Histology Laboratory).

Cytometric Bead Array (CBA)

Cytokines IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-12p70 were measured using the Mouse Inflammation Kit BD™ Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) and the BD FACS Calibur (dual laser). The samples for the cytokines assays were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the flow cytometry results were analyzed using the FCAP ArrayTM software.

Statistical Analyses

In each keratitis experiment, all animals were given a clinical score, while subsets of animals were used for bacterial yield (approximately 5–9 mice per genotype), cytokine bead array assay (3 per genotype), qRTPCR (6 per genotype) and histology (3–5 animals per genotype). In each keratitis experiment either two or three genotypes (WT and one or two other null genotype) were tested at a time, and each genotype (n = 6–8 animals per genotype) was tested 5–6 times. All animals within an experiment were of one gender. Each null genotype was compared to the WT set within an experiment carried out using multivariate linear regression to compare each null genotype to WT, while adjusting for day-to-day differences in treatment conditions. Results were considered to be significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Disease Score, Histology and Bacterial Clearance in WT and Pglyrp-null Mice

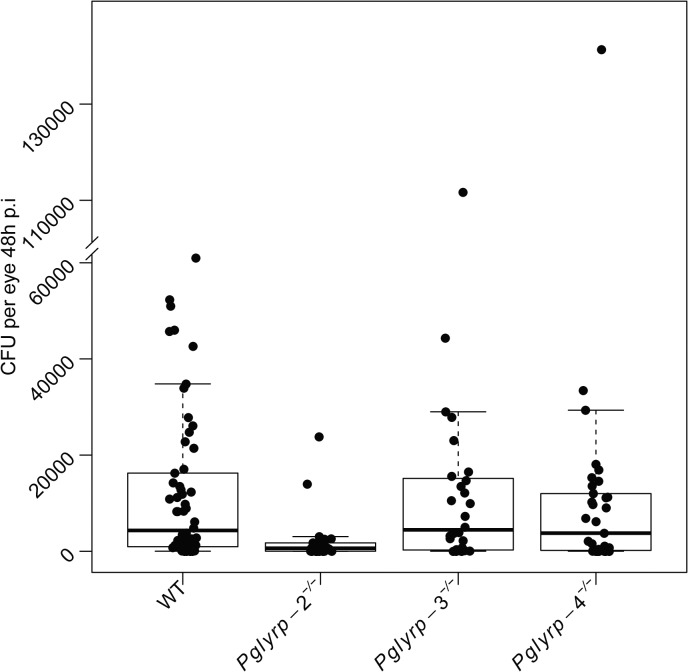

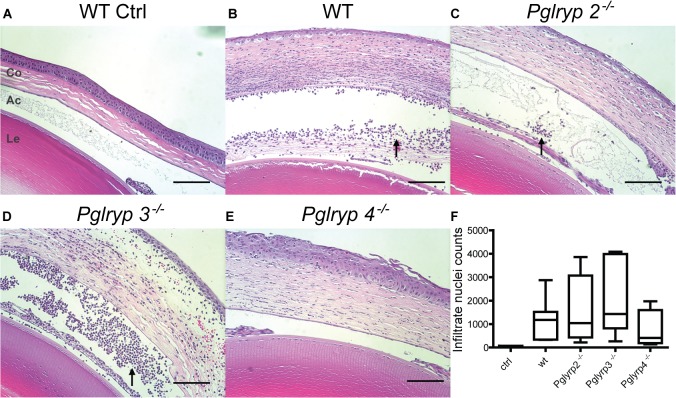

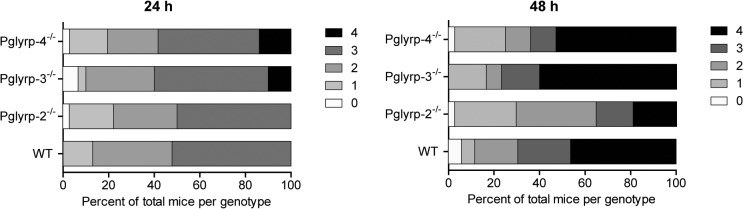

The eyes were scored in a blinded manner 24 and 48 hours after infections and harvested at the second time point for measurements of viable bacterial yield. Clinical scores after 24 hours of infection were similar in WT and Pglyrp-2 -/- mice. However, 10–13% of Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- mice had higher clinical scores, suggesting that early on disease may progress faster in these two genotypes (Fig 1A). By 48 hours of infection, the Pglyrp-2-/- mice showed significantly lower clinical disease scores compared to WT and the other null genotypes (Fig 1B). Viable bacterial yield was similar in the WT and Pglyrp-3-/- mice; bacterial yield (Fig 2) was significantly lower (t = -1.66 and p = 0.098) in the Pglyrp-4-/- mice, and even more so in the Pglyrp-2-/- mice (t = -3.45 and p = 0.0007). We also analyzed viable bacterial yield with their corresponding clinical scores (S1 Fig); in all genotypes animals with a clinical score of 4 had a range of bacterial load while those with a lower clinical score had consistently lower bacteria loads as one would expect. Histology showed robust neutrophil infiltration in infected eyes of all genotypes (Fig 3). We quantified cellular infiltrates in the cornea and the aqueous humor of infected eyes using Image J (S2 Fig) and while there was some variability, overall we found no significant difference between WT and the null mice.

Fig 1. Clinical score frequencies.

Clinical disease scores were given in a blinded manner (A) 24 and (B) 48-hours post infection (h p.i.). Results are shown as percent of animals examined in a total of 5 trials per genotype with each trial containing 6–9 animals per genotype. The Pglyrp-2-/- mice showed clinical scores comparable to WT in the 24 h.p.i group; the Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- mice had a few animals with maximal scores by 24 h.p.i suggesting escalated disease. By 48 hours the Pglyrp-2-/- mice showed reduced clinical scores.

Fig 2. Improved bacterial clearance in the Pglyrp-2-/- mice.

Dilutions of whole eye homogenates from mice harvested at 48.h.p.i were plated to obtain colony forming unit counts (CFU) per eye. Uninfected eyes did not yield viable bacteria (not shown). The Pglyrp-2-/- mouse eyes showed significantly lower viable CFU (t = -3.45, p-value = 0.0007). Bacterial yield in Pglyrp-4-/- mice were also lower than WT (t = -1.66, p-value = 0.098). Bacterial yields together with their corresponding clinical scores are shown in S1 Fig.

Fig 3. Histology of eyes 48 h.p.i.

H and E staining of parasagittal sections through the eye showing the lens (Le), anterior chamber (Ac) and the cornea (Co) (A-E). Cellular inflammatory infiltrates (arrow head) were quantified by counting the nuclei using Image J from 3–5 animals per genotype (F) (additional details provided in S2 Fig).

Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in Infected Eyes

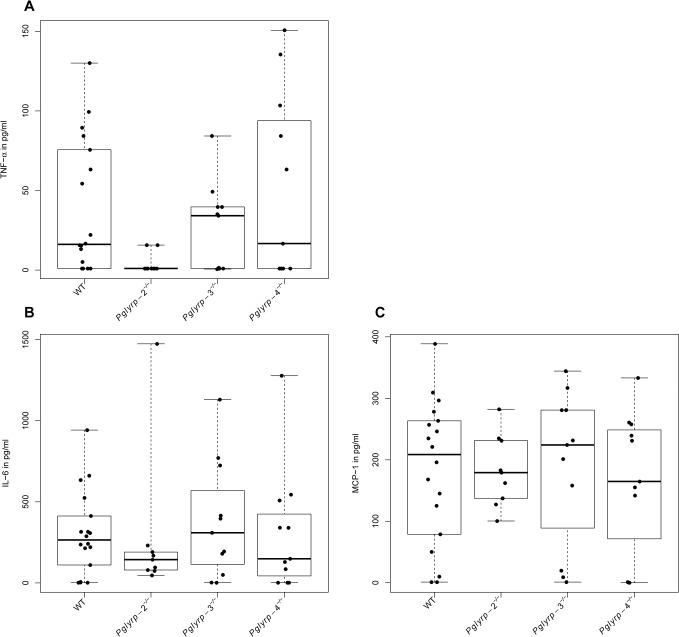

To determine whether differential cytokine production played a role in the resolution of keratitis in the Pglyrp-null mice, we measured a panel of cytokines in whole eye homogenates using a cytometric bead array assay. The cytokines assayed by this kit include IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IL-10, TNF-α, MCP-1 and IL-6. Of these, IL-12p70, IFN-γ and IL-10 could not be detected in infected or un-infected eyes of WT or of the Pglyrp-null mouse genotypes. TNF-α, MCP-1 and IL-6 were undetectable in the un-infected eyes (data not shown) and induced in the infected eyes of all genotypes. Induction of TNF-α was significantly lower in infected Pglyrp-2-/- eyes compared to WT (t = -2.4, p-value = 0.02), and while IL-6 level was also low, it was not statistically significant due to an outlier. Levels of all three cytokines were also relatively low in the Pglyrp-4-/- mice without being statistically significant (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Lower pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in the Pglyrp-2-/- infected eyes.

Cytokines in whole eye homogenates were measured 48 h. p. i. using a cytometric bead array assay. The results show individual animals from a total of 2–3 trials. Induction of TNF-α was significantly lower (t = -2.4, p = 0.02) in Pglyrp-2-/- infected eyes. Median values for MCP-1 and IL-6 were also lower in Pglyrp-2-/- mice. Median values for all three cytokines were low in the Pglyrp-4-/- infected eyes, but the mean values did not follow this trend.

Differential Expression of Pglyrp Genes in Infected Eyes

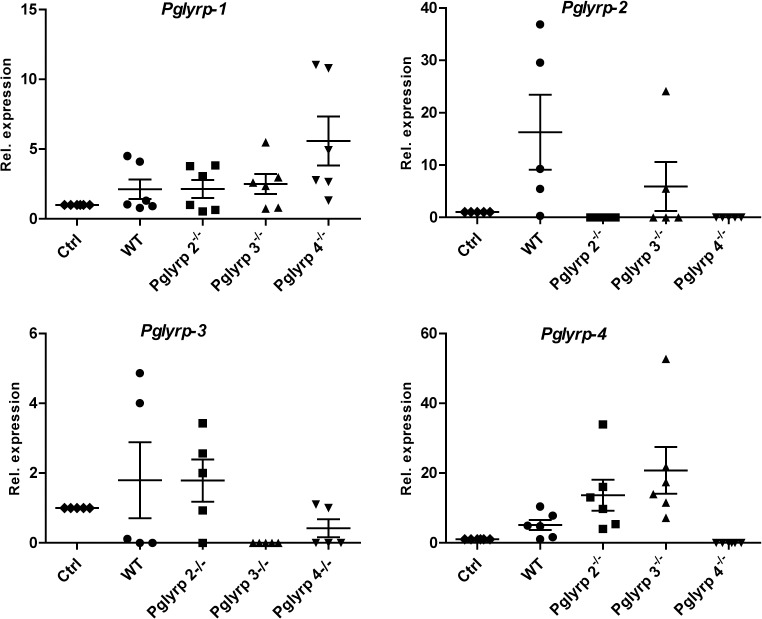

To determine if expression of any one Pglyrp is affected by deficiencies in the other Pglyrp genes we used real time qRT PCR on total RNA extracted from whole eyes to measure expression of Pglyrp1-4 in WT and each of the Pglyrp-2-4 null mouse eyes before and after infection with P. aeruginosa. Pglyrp-1 expression was constitutively high in WT and the Pglyrp- 2–4 null mice; after infection its levels increased in all genotypes without reaching statistical significance. Pglyrp-2 expression, undetectable before infection, showed variable increases after infection in WT and Pglyrp 3-/- mice, and no increase in Pglyrp 4-/- mice (Fig 5). Pglyrp-4 expression was undetectable at baseline and increased variably after infection in WT and Pglyrp 2-/- and 3-/- mice.

Fig 5. Pglyrp gene expressions regulated differentially after infection.

Relative expressions of Pglyrp-1–2, -3 and -4 compared to Gapdh were measured before and 48 h.p.i by qRTPCR on total RNA from six animals per genotype and shown here as mean ± SEM. Fold change was calculated as 2-ΔΔCt. Pglyrp-1 and -4 expressions were slightly increased after infection but these were not significant.

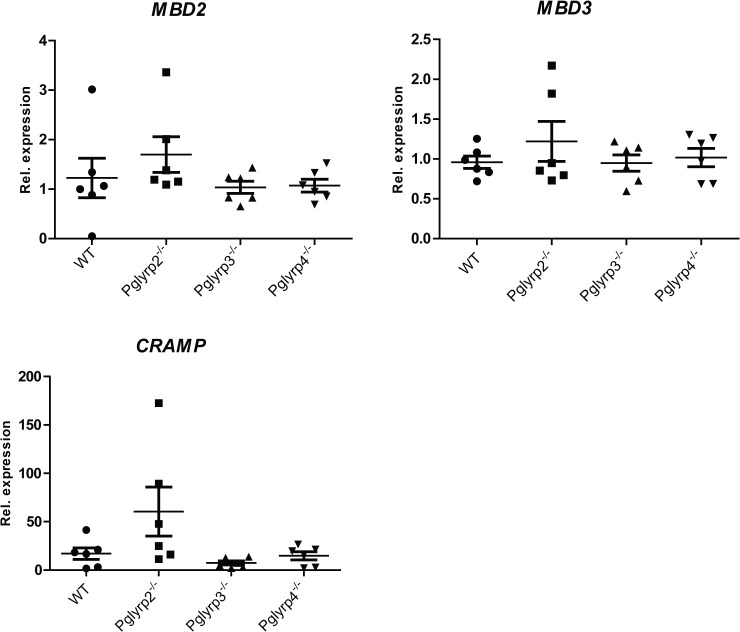

Expression of mBD2, mBD3 and CRAMP

We tested if the antimicrobial peptide genes, mBD2, mBD3 encoding β-defensins and Cnlp encoding CRAMP (cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide) are differentially expressed in the Pglyrp- null mice. We performed real time qRTPCR for mBD2, mBD3 and Cnlp (CRAMP) before and 48 hours after infection. Compared to WT infected eyes, expressions of all three antimicrobial peptide genes were very low in the Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- mice (Fig 6). The Pglyrp-2 -/- mice showed small increases in mBD2 and mBD3 expressions and a pronounced increase in CRAMP, although the data were variable and did not reach statistical significance.

Fig 6. mBD2, mBD3 and Cnlp (CRAMP) gene expressions.

The results show expression fold change (2-ΔΔCt) ± SEM of defensins and CRAMP mRNA relative to Hprt in total RNA from Pglyrp-2 -/-, Pglyrp-3 -/-, Pglyrp-4 -/- whole eyes (6 animals per genotype). Expression of mBD2, mBD3 and most notably CRAMP was increased in infected Pglyrp-2-/- eyes compared to WT without reaching statistical significance.

Discussion

To elucidate the role of Pglyrp proteins in host defense against bacterial infections of the eye, we examined the course of P. aeruginosa keratitis in mice deficient in Pglyrp-2, -3 and -4. Disease clinical scores 24 hours after infection in the WT and Pglyrp-2-/- mice were comparably low, whereas 10–13% of the animals from the Pglyrp-3-/- and 4-/- groups were scored maximally at 4. This suggests that disease may be somewhat more aggressive in the Pglyrp-3-/- and Pglyrp-4-/- genotypes, and therefore Pglyrp-3 and -4 may each have a small protective role at the early stages of infection. However, bacterial clearance in the Pglyrp-4-/- mice at the later stage was slightly better than WT. The Pglyrp-2-/- mice on the other hand showed increased resolution of overall keratitis and improved bacterial clearance. Since our previous work elucidated an antibacterial role for Pglyrp-1 [9], we wondered if compensatory over expression of Pglyrp-1 could be an underlying factor in the observed improvement in bacterial clearance. Pglyrp-1 was constitutively expressed in un-infected eyes of WT and in the other null genotypes. Furthermore, after infections Pglyrp-1 expression increased in the Pglyrp-2-4 null and WT mice. In addition, the ocular surface has several antimicrobial peptides, which could also contribute to increased disease resolution in the Pglyrp-2-/- mice.

The ocular surface is rich in antimicrobial peptides—the defensins and cathelicidins being the most studied members [15, 16]. These antimicrobial peptides function primarily by bacterial membrane perturbation and can act synergistically with other large antimicrobial proteins [17]. Our findings that transcripts for the antimicrobial peptides mBD2, mBD3 and CRAMP were increased in Pglyrp-2 -/- may in part explain the observed improvement in bacterial clearance and efficacious resolution of keratitis in these mice. An earlier study on experimental arthritis had noted that Pglyrp-2 promoted arthritis by supporting local induction of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines in a TLR4 dependent manner [18]. In our study as well inflammation was low and TNF-α was not induced to the same extent in the Pglyrp-2-/- mice as in WT mice. The clinical score is a reflection of inflammation, bacterial count and the resulting corneal clouding. Therefore, the lower clinical disease score in the Pglyrp-2 -/- mice could be due to increased bacterial clearance by CRAMP and the defensins expressed at higher levels in the Pglyrp-2-/- mice. The exact molecular events underlying the pro-inflammatory role of Pglyrp-2 are not known at the moment, but it likely interacts with innate immune signals mediated by cell surface toll-like receptors (TLRs) and cytoplasmic Nod-like receptors [19, 20].

Taken together, our study suggests that Pglyrp-3 and -4 may have some small protective functions in bacterial keratitis, as mice deficient in these two proteins showed slightly increased progression of keratitis compared to WT mice. Pglyrp-2, on the other hand may promote pro-inflammatory cytokines and dampen antimicrobial peptide expression, and the Pglyrp-2-/- mice, as a result display a milder form of keratitis. To our knowledge, our study is the first to suggest negative regulations of antimicrobial peptides by Pglyrp-2. The implications of this study are that, in vivo expressions of Pglyrp-2 must be regulated tightly to balance antimicrobial defense and inflammation to gain a favorable outcome in ocular infections and inflammation.

Supporting Information

Clinical score of each animal were plotted on 24 h. p.i (A) and 48.h.p.i (B) together with the viable bacterial yield obtained from the eyes upon harvesting at 48 hours after infection. WT and Pglyrp-2-/- mice do not show animals as having maximal clinical scores at the early 24 h. p. i. time point. However, ~ 10–13% of the Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- mice show maximal clinical scores at this point. By 48. H. p. i. A majority of the WT and Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- had scores of 3 and 4, whereas several Pglyrp-2-/- showed reduced clinical scores by this time point.

(TIF)

A) Raw image, B) Brightness adjusted to reduce collagen and RBC staining. C) Image converted to binary to further reduce non-nuclear signal. D) Anterior chamber to Bowman’s membrane was selected as the area of interest. Particle analysis was applied to the image with 20-pixel minimum, 0.2–1 circularity used as the cut-off. Counted nuclei are highlighted in yellow.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Alison McDermott for helpful comments.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by SC grant number EY021585 from National Eye Institute (https://www.nei.nih.gov) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)(http://www.nih.gov/); SC grant number EY11654 from National Institutes of Health (http://www.nih.gov/); RR grant number EY023628 from National Institutes of Health (http://www.nih.gov/) and P30-CAOO6973 (LC) from the National Institute of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Liu C, Xu Z, Gupta D, Dziarski R. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: a novel family of four human innate immunity pattern recognition molecules. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(37):34686–94. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steiner H. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: on and off switches for innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:83–96. Epub 2004/06/18. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dziarski R, Gupta D. The peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs). Genome Biol. 2006;7(8):232. Epub 2006/08/26. doi: gb-2006-7-8-232 [pii] 10.1186/gb-2006-7-8-232 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu C, Gelius E, Liu G, Steiner H, Dziarski R. Mammalian peptidoglycan recognition protein binds peptidoglycan with high affinity, is expressed in neutrophils, and inhibits bacterial growth. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(32):24490–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dziarski R, Platt KA, Gelius E, Steiner H, Gupta D. Defect in neutrophil killing and increased susceptibility to infection with nonpathogenic gram-positive bacteria in peptidoglycan recognition protein-S (PGRP-S)-deficient mice. Blood. 2003;102(2):689–97. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Royet J, Dziarski R. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: pleiotropic sensors and effectors of antimicrobial defences. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(4):264–77. Epub 2007/03/17. doi: nrmicro1620 [pii] 10.1038/nrmicro1620 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Royet J, Gupta D, Dziarski R. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: modulators of the microbiome and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(12):837–51. 10.1038/nri3089 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu F, Lee S, Schumacher M, Jun A, Chakravarti S. Differential gene expression patterns of the developing and adult mouse cornea compared to the lens and tendon. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87(3):214–25. Epub 2008/06/28. doi: S0014-4835(08)00165-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.001 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghosh A, Lee S, Dziarski R, Chakravarti S. A novel antimicrobial peptidoglycan recognition protein in the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(9):4185–91. Epub 2009/04/24. doi: iovs.08-3040 [pii] 10.1167/iovs.08-3040 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma P, Wang Z, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Toll-like receptors mediate induction of peptidoglycan recognition proteins in human corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90(1):130–6. Epub 2009/10/06. doi: S0014-4835(09)00289-9 [pii]b 10.1016/j.exer.2009.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang H, Gupta D, Li X, Dziarski R. Peptidoglycan recognition protein 2 (N-acetylmuramoyl-L-Ala amidase) is induced in keratinocytes by bacteria through the p38 kinase pathway. Infect Immun. 2005;73(11):7216–25. Epub 2005/10/22. doi: 73/11/7216 [pii] 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7216-7225.2005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zaidi TS, Zaidi T, Pier GB. Role of neutrophils, MyD88-mediated neutrophil recruitment, and complement in antibody-mediated defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(4):2085–93. Epub 2009/11/07. doi: iovs.09-4139 [pii] 10.1167/iovs.09-4139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee EJ, Evans DJ, Fleiszig SM. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExsA in penetration through corneal epithelium in a novel in vivo model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(12):5220–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zaidi TS, Priebe GP, Pier GB. A live-attenuated Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine elicits outer membrane protein-specific active and passive protection against corneal infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74(2):975–83. Epub 2006/01/24. doi: 74/2/975 [pii] 10.1128/IAI.74.2.975-983.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McDermott AM. Defensins and other antimicrobial peptides at the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2004;2(4):229–47. Epub 2007/01/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDermott AM, Redfern RL, Zhang B, Pei Y, Huang L, Proske RJ. Defensin expression by the cornea: multiple signalling pathways mediate IL-1beta stimulation of hBD-2 expression by human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(5):1859–65. Epub 2003/04/26. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415(6870):389–95. Epub 2002/01/25. doi: 10.1038/415389a 415389a [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saha S, Qi J, Wang S, Wang M, Li X, Kim YG, et al. PGLYRP-2 and Nod2 are both required for peptidoglycan-induced arthritis and local inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(2):137–50. Epub 2009/02/17. doi: S1931-3128(09)00025-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Nunez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007;27(4):549–59. Epub 2007/10/31. doi: S1074-7613(07)00455-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):373–84. Epub 2010/04/21. doi: ni.1863 [pii] 10.1038/ni.1863 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical score of each animal were plotted on 24 h. p.i (A) and 48.h.p.i (B) together with the viable bacterial yield obtained from the eyes upon harvesting at 48 hours after infection. WT and Pglyrp-2-/- mice do not show animals as having maximal clinical scores at the early 24 h. p. i. time point. However, ~ 10–13% of the Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- mice show maximal clinical scores at this point. By 48. H. p. i. A majority of the WT and Pglyrp-3-/- and -4-/- had scores of 3 and 4, whereas several Pglyrp-2-/- showed reduced clinical scores by this time point.

(TIF)

A) Raw image, B) Brightness adjusted to reduce collagen and RBC staining. C) Image converted to binary to further reduce non-nuclear signal. D) Anterior chamber to Bowman’s membrane was selected as the area of interest. Particle analysis was applied to the image with 20-pixel minimum, 0.2–1 circularity used as the cut-off. Counted nuclei are highlighted in yellow.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.