Abstract

The prognostic implications of miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 were evaluated in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients, and novel mechanism by which miR-21 contributes to the oncogenesis of DLBCL by regulating FOXO1 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was investigated. The expressions of miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 measured by quantitative reverse-transcription-PCR were significantly up-regulated in DLBCL tissues (n=200) compared to control tonsils (P=0.012, P=0.001 and P<0.0001). Overexpression of miR-21 and miR-17-92 was significantly associated with shorter progression-free survival (P=0.003 and P=0.014) and overall survival (P=0.004 and P=0.012). High miR-21 was an independent prognostic factor in DLBCL patients treated with rituximab-combined chemotherapy. MiR-21 level was inversely correlated with the levels of FOXO1 and PTEN in DLBCL cell lines. Reporter-gene assay showed that miR-21 directly targeted and suppressed the FOXO1 expression, and subsequently inhibited Bim transcription in DLBCL cells. MiR-21 also down-regulated PTEN expression and consequently activated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which further decreased FOXO1 expression. Moreover, miR-21 inhibitor suppressed the expression and activity of MDR1, thereby sensitizing DLBCL cells to doxorubicin. These data demonstrated that miR-21 plays an important oncogenic role in DLBCL by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/FOXO1 pathway at multiple levels resulting in strong prognostic implication. Therefore, targeting miR-21 may have therapeutic relevance in DLBCL.

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, miR-21, miR-17-92 cluster, miR-155, FOXO1

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and it accounts for 30-40% of the newly diagnosed cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma [1]. DLBCL is a highly heterogeneous group with variable clinical features, molecular genetic alterations, therapeutic responsiveness levels, and prognoses [2]. DLBCL can be classified into subgroups according to the cell of origin, genetic aberrations, microenvironmental signature, and dysregulated signaling pathways [1, 3, 4]. Typically, activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL shows chronic active B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling and MYD88 signaling due to recurrent genetic mutations involving CD79A/B and MYD88, which eventually leads to constitutive activation of NF-κB [5]. BCR and MYD88 signaling have also been shown to activate the PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT pathways to promote cell survival in cooperation with the NF-κB pathway [5, 6]. In contrast, germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCLs have been shown to be addicted to the oncogenic activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway [7]. Moreover, AKT activation is associated with poor prognosis of DLBCL patients [8]. However, the mechanism underlying the activation of PI3K/AKT pathway and its oncogenic role in DLBCL remain unclear.

MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs of 20-22 nucleotides implicated in a variety of physiological and pathological processes [9]. In the hematolymphoid system, miRNAs play a pleiotropic role and are involved in B-cell differentiation and malignant transformation. Several miRNAs also regulate oncogenic or tumor-suppressive pathways, such as the NF-κB or BCR signaling, in lymphoma [10, 11]. MiR-21, the miR-17-92 cluster (miR-17-92 hereafter) and miR-155 are well-known oncogenic miRNAs, which mostly target tumor-suppressive molecules in many cancers [12]. Overexpression of miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 were observed in several lymphomas derived from B-cells, T-cells or NK-cells, showing diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic potentials [10, 13-15].

Specifically, miR-21 played an important role in pre-B-cell lymphomagenesis, and inactivation of miR-21 caused the regression of tumors via apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in a mouse model [16]. MiR-21 was also reported to regulate the chemosensitivity of DLBCL cells [17]. MiR-17-92 was the first miRNA identified as dysregulated in DLBCL [18], and was demonstrated to induce B-cell leukemia in concert with MYC [19, 20]. MiR-155 directly targets SMAD5 and to help lymphoma cells escape from TGF-β-mediated growth-inhibition [21].

However, the status of miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 and their clinicopathological implications are not fully elucidated in patients with DLBCL. Moreover, the mechanisms by which they contribute to the pathogenesis of human DLBCLs are not completely understood. Thus, in this study, we analyzed the association of the miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 expression with the clinicopathological features and prognosis of patients with DLBCL. Furthermore, we investigated the role of miR-21 in the modulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in DLBCL cells, and we discovered that FOXO1 is a novel direct target of miR-21.

RESULTS

MiR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 expression levels in DLBCL patients and their associations with the clinicopathological features

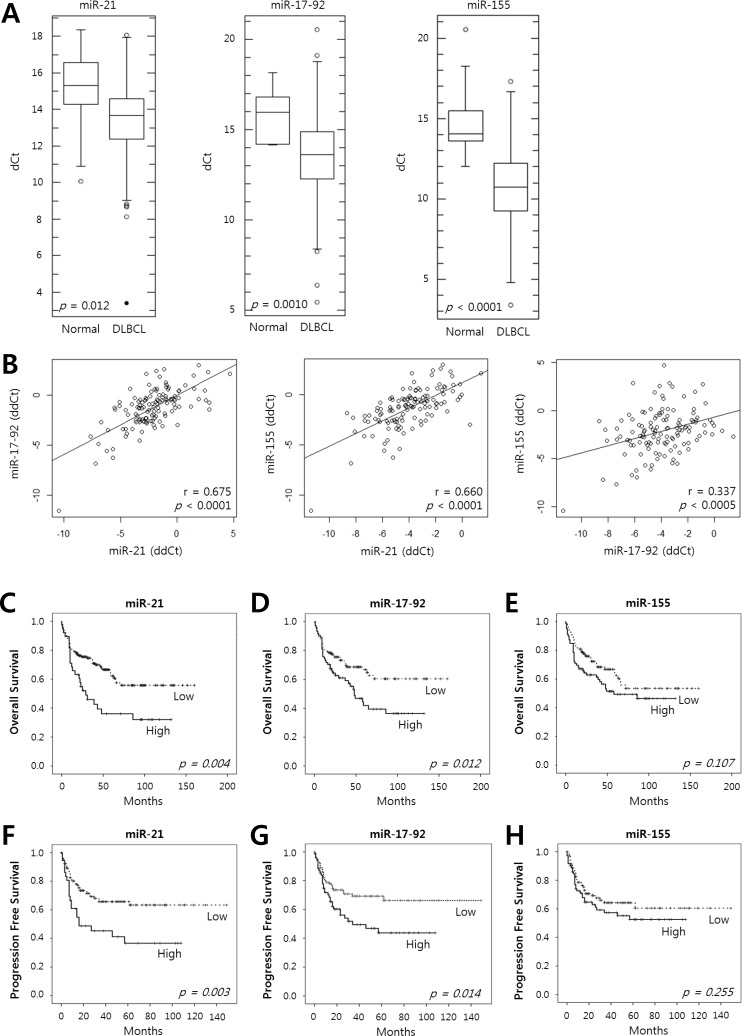

The expression levels of miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 in the DLBCL tissues determined using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) were significantly up-regulated and showed lower dCt values compared to those of controls (P = 0.012, P = 0.001, P <0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 1A). The expression levels of these miRNAs relative to those of normal tonsils, as represented by ddCt values, showed significant positive correlations with each other (miR-21 vs. miR-17-92, P <0.0001; miR-21 vs. miR-155, P < 0.0001; miR-17-92 vs. miR-155, P <0.0005) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Expression of miR-21, the miR-17-92 cluster and miR-155 in tumor tissues of DLBCL patients and their prognostic implications.

A, The levels of expression of miR-21, the miR-17-92 cluster and miR-155 were evaluated in the tumor tissues of DLBCL patients (n = 200) and in normal tonsils as a control (n = 11) using qRT-PCR. Box-and-whisker plots demonstrate the levels of expression of miR-21, the miR-17-92 cluster, and miR-155 as dCt (= Ct(miRNA) - Ct(U6)) values in the DLBCL tissues compared with those in normal tonsils. A lower dCt implies a higher relative level of miRNA. The differences in the miRNA levels of the DLBCL and normal group were evaluated using Student's t-test. B, The relative expression levels of the miRNAs were calculated as ddCt (= dCt(case) - mean dCt(control)). The diagrams show the correlation of the relative expression levels of miR-21, the miR-17-92 cluster and miR-155 determined using Pearson's correlation analysis (r, correlation coefficient). Kaplan-Meier curves obtained using the log-rank test show C-E, the overall survival and F-H, the progression-free survival of patients with DLBCLs with high vs. low relative expression levels of miR-21, the miR-17-92 cluster, and miR-155.

To analyze the clinicopathological features and the prognoses of the patients according to the miRNA expression, we classified the DLBCL patients into two groups, i.e., those with high vs. low miRNA levels relative to controls according to the 2−ddCt values described in Methods. As summarized in Table 1, miR-21 was significantly overexpressed in DLBCLs that presented at an advanced stage (P = 0.011), and the miR-17-92 expression was significantly higher in patients with older age (P = 0.019) or a poor performance status (PS) (P = 0.012). High miR-155 expression was also significantly associated with adverse clinicopathological features, including an older age (P = 0.003), an advanced stage (P = 0.018), a higher revised-International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) (P = 0.031), the presence of B symptoms (P = 0.003), a poor PS (P = 0.049), and ABC subtype (P = 0.043) (Table 1). The higher expression of miR-155 in the ABC subtype than in the GCB subtype was consistent with the results of a previous report [22].

Table 1. Correlations between the miRNA expression levels and the clinicopathological variables in patients with DLBCL.

| Variablesa | miR-21 | miR-17-92 cluster | miR-155 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 200) | Low (n = 162) | High (n = 38) | P | Low (n = 126) | High (n = 74) | P | Low (n = 121) | High (n = 79) | P | |

| Age | ||||||||||

| Mean (range) | 58.1(8-86) | 57.56(8-86) | 60.58(12-85) | 0.271 | 56.2(8-86) | 61.4(12-85) | 0.019 | 55.72(8-86) | 61.84(23-85) | 0.003 |

| <60 | 90 | 76(84.4%) | 14(15.6%) | 0.261 | 63(70.0%) | 27(30.0%) | 0.064 | 63(70.0%) | 27(30.0%) | 0.013 |

| ≥60 | 110 | 86(78.2%) | 24(21.8%) | 63(57.3%) | 47(42.7%) | 58(52.7%) | 52(47.3%) | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 113 | 92(81.4%) | 21(18.6%) | 0.864 | 78(69.0%) | 35(31.0%) | 0.044 | 71(62.8%) | 42(37.2%) | 0.442 |

| Female | 87 | 70(80.5%) | 17(19.5%) | 48(55.2%) | 39(44.8%) | 50(57.5%) | 37(42.5%) | |||

| Primary Site | ||||||||||

| Nodal | 61 | 47(77.0%) | 14(23.0%) | 0.345 | 39(63.9%) | 22(36.1%) | 0.856 | 31(50.8%) | 30(49.2%) | 0.064 |

| Extranodal | 139 | 115(82.7%) | 24(17.8%) | 87(62.6%) | 52(37.4%) | 90(64.7%) | 49(35.3%) | |||

| Stage | ||||||||||

| 1,2 | 107 | 93(86.9%) | 14(13.1%) | 0.011 | 72(67.3%) | 35(32.7%) | 0.117 | 72(67.3%) | 35(32.7%) | 0.018 |

| 3,4 | 87 | 63(72.4%) | 24(27.6%) | 49(56.3%) | 38(43.7%) | 44(50.6%) | 43(49.4%) | |||

| R-IPI group | ||||||||||

| Very good + Good | 114 | 96(84.2%) | 18(15.8%) | 0.120 | 75(65.8%) | 39(34.2%) | 0.179 | 75(65.8%) | 39(34.2%) | 0.031 |

| Poor | 63 | 47(74.6%) | 16(25.4%) | 35(55.6%) | 28(44.4%) | 31(49.2%) | 32(50.8%) | |||

| B symptom | ||||||||||

| Absent | 159 | 131(82.4%) | 28(17.6%) | 0.139 | 98(61.6%) | 61(38.4%) | 0.652 | 102(64.2%) | 57(35.8%) | 0.003 |

| Present | 35 | 25(71.4%) | 10(28.6%) | 23(65.7%) | 12(34.3%) | 13(37.1%) | 22(62.9%) | |||

| Bulky | ||||||||||

| Absent | 174 | 141(81.0%) | 33(19.0%) | 0.597 | 107(61.5%) | 67(38.5%) | 0.374 | 107(61.5%) | 67(38.5%) | 0.100 |

| Present | 21 | 16(76.2%) | 5(23.8%) | 15(71.4%) | 6(28.6%) | 9(42.9%) | 12(57.1%) | |||

| Performance status | ||||||||||

| 0-1 | 146 | 120(82.2%) | 26(17.8%) | 0.247 | 98(67.1%) | 48(32.9%) | 0.012 | 92(63.0%) | 54(37.0%) | 0.049 |

| ≥2 | 47 | 35(74.5%) | 12(25.5%) | 22(46.8%) | 25(53.2%) | 22(46.8%) | 25(53.2%) | |||

| Serum LDH | ||||||||||

| Normal | 77 | 65(84.4%) | 12(15.6%) | 0.295 | 48(62.3%) | 29(37.7%) | 0.983 | 50(64.9%) | 27(35.1%) | 0.246 |

| Elevated | 96 | 75(78.1%) | 21(21.9%) | 60(62.5%) | 36(37.5%) | 54(56.2%) | 42(43.8%) | |||

| Extranodal sites (n) | ||||||||||

| 0.1 | 153 | 126(82.4%) | 27(17.6%) | 0.163 | 98(64.1%) | 55(35.9%) | 0.293 | 93(60.8%) | 60(39.2%) | 0.507 |

| ≥2 | 40 | 29(72.5%) | 11(27.5%) | 22(55.0%) | 18(45.0%) | 22(55.0%) | 18(45.0%) | |||

| Bone marrow involvement | ||||||||||

| Absent | 154 | 125(81.2%) | 29(18.8%) | 0.546 | 96(62.3%) | 58(37.7%) | 0.873 | 90(58.4%) | 64(41.6%) | 0.600 |

| Present | 25 | 19(76.0%) | 6(24.0%) | 16(64.0%) | 9(36.0%) | 16(64.0%) | 9(36.0%) | |||

| Rituximab treatment | ||||||||||

| No | 91 | 68(74.7%) | 23(25.3%) | 0.052 | 57(62.6%) | 34(37.4%) | 0.975 | 55(60.4%) | 36(39.6%) | 0.843 |

| Yes | 105 | 90(85.7%) | 15(14.3%) | 66(62.9%) | 39(37.1%) | 62(59.0%) | 43(41.0%) | |||

| GCB vs. ABC (Choi) | ||||||||||

| GCB | 53 | 45(84.9%) | 8(15.1%) | 1.000 | 36(67.9%) | 17(32.1%) | 0.743 | 38(71.7%) | 15(28.3%) | 0.043 |

| ABC | 95 | 79(83.2%) | 16(16.8%) | 62(65.3%) | 33(34.7%) | 52(54.7%) | 43(45.3%) | |||

R-IPI, revised-international prognostic index; GCB, germinal center B cell-like; ABC, activated B-cell like

Several variables contain missing values due to the lack of relevant information in the patients.

Prognostic implication of miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 expression levels in DLBCL patients

The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that a high expression of miR-21 and miR-17-92 was significantly associated with decreased overall survival (OS) (P = 0.004 and P = 0.012, respectively) (Fig. 1C and 1D) and progression-free survival (PFS) (P = 0.003 and P = 0.014, respectively) (Fig. 1F and 1G) but miR-155 was not (Fig. 1E and H). The multivariate Cox analysis showed that a high miR-21 was an independent predictor for poor survival in the overall patients with DLBCL (for OS, HR = 2.1, P = 0.020; for PFS, HR = 2.3, P = 0.032) and in those treated with rituximab-combined chemotherapy (for OS, HR = 2.4, P = 0.032; for PFS, HR = 2.8, P = 0.030) (Table 2). Moreover, a high miR-17-92 was also an independent predictor for poor PFS in overall patients (HR = 2.2; P = 0.023) and in those treated with rituximab-combined chemotherapy (HR = 2.6; P = 0.030) but not for their OS (data not shown). When the data were evaluated according to the immunophenotypical subgroups of DLBCLs, high miR-21 was significantly correlated with a shorter OS and PFS in the GCB subgroup (for OS, HR = 6.0 and P = 0.001; for PFS, HR = 5.4 and P = 0.001) but not in the ABC subgroup (Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S1). Together, these data indicated that miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 are frequently overexpressed in DLBCL tissues and that high levels of miR-21 and miR-17-92 expression are correlated with a poor clinical outcome for the DLBCL patients. In particular, miR-21 was an independent prognostic indicator for both the PFS and OS of patients with DLBCL.

Table 2. Prognostic implications of miR-21 expression in DLBCL patients evaluated using the multivariate Cox-regression model.

| All patients | Rituximab treated-patientsa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| miR-21(high vs. low) | 2.1 | 1.1–3.9 | 0.020 | 2.4 | 1.1–5.4 | 0.032 |

| R-IPI (Poor vs. Very good + Good) | 4.0 | 2.2–7.2 | <0.001 | 2.8 | 1.1–5.4 | 0.022 |

| Subtype (GCB vs. ABC) | 1.0 | 0.5–1.9 | 0.991 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.8 | 0.606 |

| Progression-free survival | ||||||

| miR-2 I (high vs. low) | 2.3 | 1.1–4.8 | 0.032 | 2.8 | 1.14.9 | 0.030 |

| R-IPI (Poor vs. Very good + Good) | 3.0 | 1.5–6.1 | 0.002 | 1.7 | 0.74.1 | 0.206 |

| Subtype (GCB vs. ABC) | 1.1 | 0.6–2.4 | 0.717 | 1.7 | 0.7–4.3 | 0.281 |

R-1P1, revised-international prognostic index; GCB, germinal center B cell-like: ABC, activated B-cell like

Of the rituximab-treated patients, 85.74 (90/105) were treated using the R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone) regimen.

Forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) are targeted by miR-21 in DLBCLs

Because miR-21 had the strongest prognostic implication, we explored the mechanism by which miR-21 contributes to the pathogenesis of DLBCLs. For this purpose, we focused on FOXO1 and PTEN among the many possible targets of miR-21 that were identified using database and literature searches (e.g., www.microrna.org and www.targetscan.org) [17, 23]. PTEN is a tumor suppressor that inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway and a well-known direct target of miR-21 [23, 24]. FOXO1 is a transcription factor for p27, p21, FasL, and Bim, which function as tumor suppressors by blocking the G1/S transition and inducing apoptosis [25-27]. Notably, FOXO1 is also a downstream molecule of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Activated AKT phosphorylates FOXO1, which is subsequently exported from the nucleus into the cytoplasm and degraded by proteasomes [28]. Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-21 might modulate the PI3K/AKT pathway by targeting PTEN upstream and FOXO1 downstream.

To address this hypothesis, we first screened the expression levels of miR-21, FOXO1 and PTEN in a variety of DLBCL cell lines. As shown in Fig. 2A, the miR-21 expression level was inversely correlated with both the FOXO1 and PTEN levels in DLBCL cells. Furthermore, PTEN expression was low in the GCB-DLBCL-derived cell lines compared to the ABC-DLBCL-derived cell lines (Fig. 2A). This expression pattern of PTEN in DLBCL cells was consistent with a previous report [7]. For further study, SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells, which have high miR-21/low FOXO1/low PTEN expression, and OCI-Ly10 cells, which have low miR-21/high FOXO1/high PTEN expression, were selected. The expression of FOXO1 and PTEN were significantly increased in SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 by transfection with a miR-21 inhibitor (Fig. 2B). Consistently, transfection with miR-21 mimics resulted in the significant down-regulation of PTEN and FOXO1 in OCI-Ly10 (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, transfection with miR-21 mimics led to decreased FOXO1 mRNA 3′-UTR luciferase activity, but miR-21 inhibitor increased its luciferase activity (Fig. 2D). Considering the function of FOXO1 as transcription factor we evaluated the alteration of nuclear FOXO1 level by miR-21. As shown in Fig. 2E, nuclear FOXO1 was increased in SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 by miR-21 inhibitor but decreased in OCI-Ly10 cells by miR-21 mimics.

Figure 2. FOXO1, which is directly targeted by miR-21 in addition to PTEN, controls Bim expression at a transcriptional level in DLBCLs.

A, The expression levels of miR-21, FOXO1, and PTEN were evaluated in GCB-DLBCL and ABC-DLBCL cell lines using qRT-PCR. The bar graph shows the relative expression levels (2−ddCt) of miR-21, FOXO1, and PTEN in each cell line compared with those of OCI-Ly1 cells. B, SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells were transfected with a miR-21 inhibitor or a negative (scramble) inhibitor using Lipofectamine 2000, and the cells were harvested at 24 hours after transfection. The expression levels of FOXO1 and PTEN in cells that were transfected with the miR-21 inhibitor were compared with those transfected with the negative inhibitor using qRT-PCR. C, OCI-Ly10 cells were transfected with miR-21 mimics or negative (scramble) mimics, and the differences in the expression levels of FOXO1 and PTEN between the negative- and miR-21 mimic-cells were assessed using qRT-PCR. D, The FOXO1 3′-untranslated region (UTR)-luciferase reporter construct containing many miR-21 binding motifs (5′-AGCUUAU-3′) was co-transfected into SU-DHL-4 and SU-DHL5 cells together with a miR-21 mimic, negative mimic, miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor. At 24 hours post-transfection, the supernatant fractions of the lysed cells were recovered, and the luciferase activities were determined using a luminometer. E, At 24 hours after transfection of the miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor into SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells, or miR-21 mimics or negative mimics into OCI-Ly10 cells, Western blotting was performed to determine FOXO1 level in the nucleus of tumor cells. F, Changes in the expression of FOXO1 target genes, including p27, p21, FasL and Bim, were evaluated using qRT-PCR after inhibiting the expression of miR-21 in SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells. G, A Bim promoter luciferase-reporter construct containing many copies of the FOXO1 binding motif (5′-GTAAACAA-3′) was co-transfected with either a miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor into SU-DHL4 or SU-DHL5 cells. At 24 hours post-transfection, the supernatant fractions of the lysed cells were recovered, and the luciferase activities were measured using a luminometer. The values presented in the histogram are the mean values ± SD. Statistically significant differences are indicated by * and **, which signify P < 0.05 and P < 0.005, respectively, as determined using the paired t-test.

In human DLBCL tissues, FOXO1 expression was observed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in 80.8% (126/156) of the cases with variable intensities and staining patterns, which were related to the miR-21 level. Briefly, cases with a low miR-21 showed increased nuclear expression of FOXO1, whereas those with a high miR-21 frequently exhibited cytoplasmic expression (Supplementary Fig. S2A). For the statistical analysis, the FOXO1-IHC score was calculated as the nuclear intensity minus the cytoplasmic intensity. Accordingly, the patients were divided into two groups, i.e., those with predominant nuclear staining (a FOXO1-IHC score of ≥ 0) and those with predominant cytoplasmic staining (a score of < 0). Nuclear predominant FOXO1 was significantly correlated with a low miR-21in the DLBCL tissues (P = 0.0002) (Supplementary Fig. S2B).

Taken together, these data indicate that miR-21 suppresses FOXO1 and PTEN expression in DLBCL and that FOXO1 is a direct target of miR-21 in DLBCL cells.

MiR-21-regulated FOXO1 controls Bim expression at a transcriptional level

To determine the function of FOXO1 regulated by miR-21 in DLBCL, we investigated the changes of FOXO1 transcriptional target molecules, including p27, p21, FasL and Bim. Notably, transfection of SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells with the miR-21 inhibitor resulted in the up-regulation of Bim expression but had little effect on the others (Fig. 2F). Moreover, miR-21 inhibitor increased the luciferase activity of vectors containing the 5′-FOXO1-binding sites of the Bim promoter region in these cells, which suggested that Bim expression is increased at the transcriptional level by FOXO1 (Fig. 2G). Consistently, treatment with a transcriptional inhibitor (actinomycin D) blocked the induction of Bim even after the miR-21 inhibitor transfection (Supplementary Fig. S3).

In human DLBCL tissues, Bim expression showed a tendency of inverse relationship with the miR-21 expression. Briefly, Bim mRNA level was lower in high miR-21 group compared to low miR-21 group (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Bim expression by IHC was categorized into low (none to mild) vs. high (moderate to strong) according the staining intensity. Among cases with high miR-21, low Bim expression was more commonly observed rather than high Bim expression. In contrast, high Bim expression was more frequent in those with low miR-21 although the difference was statistically insignificant (Supplementary Fig. S4B).

Taken together, these data indicated that FOXO1 up-regulates pro-apoptotic Bim at the transcriptional level and thus FOXO1/Bim axis would be an important pathway that is regulated by miR-21 in DLBCLs.

MiR-21 activates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and FOXO1 inactivates mTOR in DLBCL

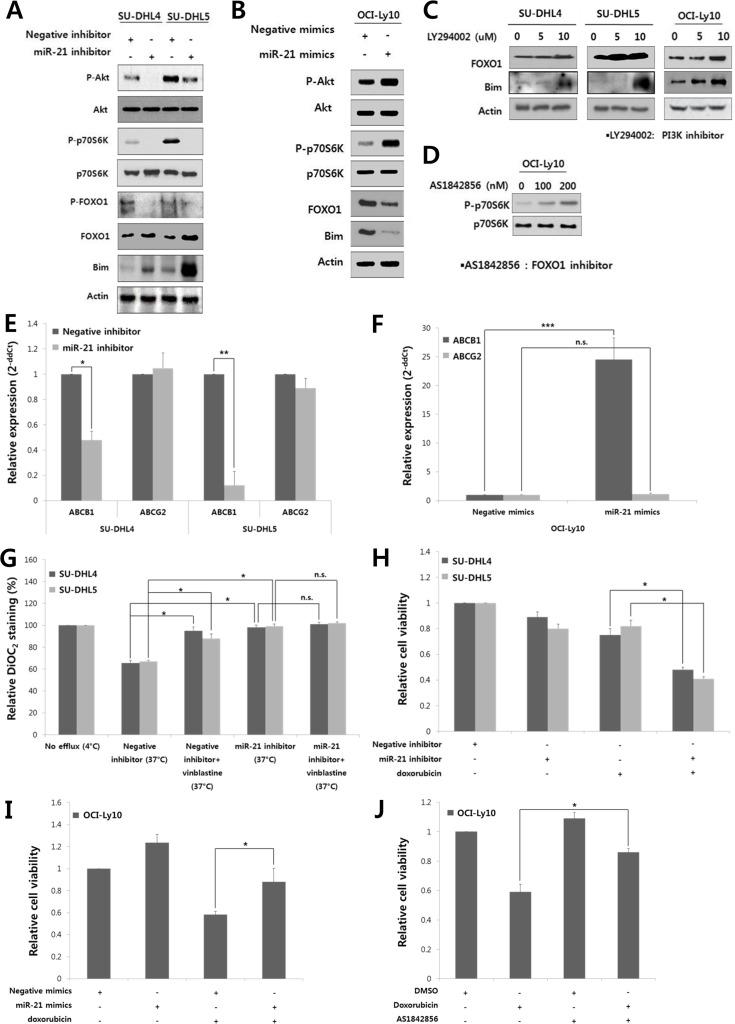

Given that the expression of FOXO1 and PTEN was down-regulated by miR-21 in DLBCLs (Fig. 2B and C), we further investigated if miR-21 activated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. MiR-21 inhibitor suppressed AKT and mTOR activity as shown by decrease in phospho-AKT and phospho-70S6K in SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells (Fig. 3A). At the same time, the phospho-FOXO1 level was diminished, but the amount of total FOXO1 was increased along with Bim up-regulation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, miR-21 mimics activated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in OCI-Ly10 cells but down-regulated FOXO1 and Bim (Fig. 3B). These data suggested that miR-21 activates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in DLBCL. Accordingly, miR-21 inhibition rescued FOXO1 from AKT activity-mediated phosphorylation and putatively subsequent degradation. Consistently, a functional inhibitor of PI3K, LY294002, up-regulated the expression of FOXO1 and Bim in DLBCL cells (Fig. 3C), which further suggested that the FOXO1/Bim axis may be an important target regulated by the PI3K/AKT signaling in DLBCL.

Figure 3. MiR-21 regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/FOXO1 pathway and involved in the drug resistance and proliferation of DLBCL cells.

At 24 hours after transfection of A, the miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor into SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells or B, miR-21 mimics or negative mimics into OCI-Ly10 cells, Western blotting was performed to determine the levels of phospho-AKT, AKT, phospho-p70S6K, p70S6K, phospho-FOXO1, FOXO1 and Bim. C, SU-DHL4, SU-DHL5, and OCI-Ly10 cells were treated with increasing doses of LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor. At 24 hours after incubation, Western blotting was performed to determine the levels of FOXO1 and Bim. D, OCI-Ly10 cells were treated with increasing doses of AS1842856, a functional inhibitor of FOXO1, and 2 hours after incubation, Western blotting was performed to determine the levels of phospho-p70S6K and p70S6K. At 24 hours after transfection of E, the miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor into SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells, or F, miR-21 mimics or negative mimics into OCI-Ly10 cells, the expression levels of ABCB1 (MDR1) and ABCG2 were evaluated using qRT-PCR. G, SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells were treated with the miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor for 24 hours and co-incubated with the efflux-blocking drug, vinblastine, for the last 30 minutes. The cells were then stained with DiOC2, and their drug efflux activity was analyzed. A decrease in the percentage of DiOC2-staining cells determined using FACS represents an increase in the population of cells with drug efflux activity. H, The effect of miR-21 inhibition on the doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity in SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells was evaluated using the CCK8 assay. I, The effect of miR-21 overexpression on the doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity in OCI-Ly10 cells was assessed using the CCK8 assay. J, The relative rates of cell proliferation of OCI-Ly10 cells treated with DMSO (control) and doxorubicin and/or the FOXO1 inhibitor (AS1842856) were determined using the CCK8 assay. The values presented in the histogram are the mean values ± SD. Statistically significant differences are indicated by *, ** and ***, which signify P < 0.05, P < 0.005 and P < 0.0005, respectively, as determined using the paired t-test.

To further see the role of FOXO1 in PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway of DLBCL, we examined if FOXO1 had an inhibitory effect on mTOR activity as previously reported in other types of cells [29, 30]. A functional inhibitor of FOXO1, AS1842856, activated mTOR pathway as shown by increased phospho-p70S6K in OCI-Ly10 cells (Fig. 3D).

Taken together, these results indicated that miR-21 suppresses FOXO1 and its transcriptional target Bim directly by binding to the 3′-UTR of FOXO1 and indirectly by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway in DLBCL.

MiR-21 up-regulates the expression and activity of multidrug resistant protein 1 (MDR1) to induce drug resistance in DLBCL cells

Finally, we evaluated the effect of miR-21 on cell viability and drug resistance in DLBCL. MDR1 (encoded by the ABCB1 gene) functions as drug efflux pump with broad substrate specificity [31], and is known to be up-regulated by AKT activity [32]. Thus, we examined if miR-21 affected MDR1 expression in DLBCL cells. The miR-21 inhibitor transfection in SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells significantly suppressed the MDR1 expression, but with little effect on another transport-related protein, ABCG2 (Fig. 3E). In contrast, miR-21 mimics up-regulated the expression of MDR1 but not of ABCG2 in OCI-Ly10 cells (Fig. 3F). DiOC2 was effluxed from SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells by up to 40% at the basal level (Fig. 3G, “negative inhibitor (37°C)”), which was blocked by vinblastine (an efflux-blocking agent). Notably, the drug efflux activity was significantly blocked by the miR-21 inhibitor (Fig. 3G).

In addition, the miR-21 inhibitor reduced the proliferation of SU-DHL4 and SU-DHL5 cells (Supplementary Fig. S5). Combined treatment with the miR-21 inhibitor and doxorubicin synergistically suppressed the proliferation and viability of these cells (Fig. 3H). In contrast, treatment with miR-21 mimics increased the proliferation of OCI-Ly10 cells and antagonized the cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin (Fig. 3I). Interestingly, the cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin was also antagonized by a FOXO1 inhibitor (AS1842856) in OCI-Ly10 cells (Fig. 3J). These data indicated that miR-21 and FOXO1 may be involved in the drug resistance of DLBCL cells and that miR-21 inhibition can sensitize these cells to doxorubicin.

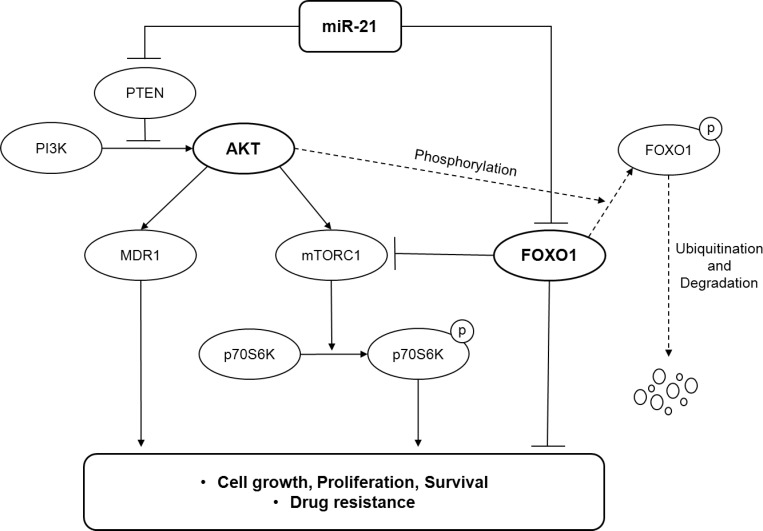

Considering all of the results in this study, we propose a model in which miR-21 plays an oncogenic role by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and suppressing the FOXO1/Bim pathway at multiple levels in DLBCL (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. A model illustrating the regulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/FOXO1 pathway by miR-21 at multiple levels in DLBCL.

DISCUSSION

Although miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 are oncogenic miRNAs reported to be overexpressed in DLBCL [10, 23], comprehensive analysis of these miRNAs in a large cohort of DLBCL patients was rare, and their prognostic implications were conflicting depending on the types of patients-derived samples and study cohort [33, 34]. In the present study, the expressions of the miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 were significantly up-regulated in DLBCL tissues, and their levels showed a strong positive correlation with each other. To avoid the confounding effect of the treatment regimen, we investigated the prognostic implications of miRNAs in patients with rituximab treatment and in overall patients, respectively, because patients who did not treated with rituximab were received variable treatment regimens such as CHOP, COPBLAM (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin, doxorubicin and procarbazine) and HDMTX (high dose methotrexate). Overexpression of these miRNAs was associated with adverse clinicopathological features, and high miR-21 and miR-17-92 were independent poor prognostic factors in overall DLBCL patients and those treated with rituximab. These data suggested that miR-21, miR-17-92 and miR-155 might cooperatively contribute to the pathogenesis of DLBCL and that they are important constituents forming an oncogenic miRNA signature of DLBCLs with a poor clinical outcome. Although we determined the levels of the premature miRNAs using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, it has been reported that the expression levels of premature miRNAs are well correlated with those of mature miRNAs [35, 36]. Considering that the miRNA levels in tumor tissues and serum show strong positive correlations [34], the serum levels of the miRNAs analyzed in this study could be utilized as prognostic biomarkers.

This study demonstrated that FOXO1 is a novel direct target of miR-21 and is implicated in the pathogenesis of DLBCL [27]. FOXO1 is also important for the development and differentiation of B-cell [37], and the inactivation of FOXO1 is required for optimal B-cell proliferation [38]. Regarding the lymphoid malignancies, FOXO1 was shown to be a tumor suppressor in Hodgkin lymphoma [39]. Dysregulation of FOXO1 by an inactivating mutation has been recently reported in DLBCLs [40]. However the functional role of FOXO1 in the pathogenesis of DLBCL remains unknown. In our study, the inhibition of FOXO1 resulted in resistance to apoptotic stimuli (i.e., doxorubicin), thereby suggesting a pro-apoptotic role for FOXO1 in DLBCL cells. Moreover, the pro-apoptotic Bim was up-regulated by FOXO1 following the inhibition of miR-21, but other FOXO1 target molecules, including p27, p21, and FasL, were not affected. FOXOs interact with various transcriptional cofactors, which are suspected to specify the target genes of FOXO1 [26]. For example, RUNX3 in cooperation with FOXO up-regulates Bim in gastric cancer cells [41]. Therefore, it is possible that cofactors may contribute to the selective regulation of the FOXO1/Bim axis by miR-21 in the DLBCL cells. Together, the results of the present study demonstrate that FOXO1 may function as a tumor suppressor in DLBCLs.

Despite mounting evidence of a tumor suppressive role for FOXO1, the mechanism by which FOXO1 activity is regulated remains unclear. It has been known that FOXO1 activity is generally regulated by posttranscriptional modification rather than genetic aberration [42, 43]. Deletion of genetic loci encompassing FOXO1 was observed in only a portion of Hodgkin lymphomas, and a FOXO1 mutation accounted for 8.6% of DLBCL cases [39, 40]. Moreover, the level of FOXO1 expression was not dependent on the FOXO1 mutation in DLBCLs [40], which suggests that other factors might be involved in the regulation of FOXO1 expression in DLBCLs. Other mechanisms reported to be important for the regulation of FOXO1 are PI3K/AKT signaling and miRNA [39, 42]. Exclusion of FOXO1 from the nucleus and thus its presence in the cytoplasm was been observed in DLBCLs showing chronic active BCR signaling or PI3K/AKT activation [44]. Among the miRNAs, miR-27a, miR-96, miR-182, and miR-183 suppressed FOXO1 expression in breast cancer, melanoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma [39, 42]. However, the association between miR-21 and FOXO1 expression has never been addressed. This study demonstrated that miR-21 down-regulated FOXO1 in both direct and indirect manners by binding the 3′-UTR of FOXO1 and by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway in DLBCLs.

The PI3K/AKT pathway is regarded to be an important oncogenic signaling pathway in both the GCB and ABC types of DLBCL [5, 7]. Activation of the PI3K signaling blocks apoptosis and is required for constitutive NF-κB activation in ABC-DLBCL [45]. However, the loss of PTEN occurs in only 14% of non-GCB DLBCLs, and ABC-DLBCL cells often show AKT activation even in the presence of PTEN [7]. Therefore, activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in ABC-DLBCLs has been suspected to be independent of PTEN. In contrast, the loss of PTEN occurs in 55% of GCB-DLBCLs, and AKT activation in GCB-DLBCL cells is frequently associated with the PTEN loss, which makes tumor cells addicted to oncogenic PI3K signaling [7]. However, the mechanism of PTEN downregulation in DLBCLs remains to be elucidated. In this study, we demonstrated that miR-21 activated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by targeting PTEN at the upstream level and by targeting the FOXO1/Bim pathway at the downstream level as schematically illustrated in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the present study showed that FOXO1 activity may counteractively inhibit the mTORC1 pathway in DLBCL cells. Moreover, miR-21 had a prognostic significance for DLBCL patients with the GCB phenotype but not the ABC phenotype. Thus, we suggest that miR-21 might be involved in the oncogenic addiction of GCB-DLBCLs to the PI3K/AKT pathway.

In this study, miR-21 inhibition suppressed DLBCL cell proliferation and sensitized the DLBCL cells to doxorubicin. These data were consistent with those of a previous report showing that miR-21 expression was correlated with chemoresistance in DLBCL cells, which was mediated by PTEN suppression [17]. Here, we further showed that miR-21-mediated chemoresistance involved the up-regulation of MDR1 expression and activity. In addition, considering that the level of Bim predicts the sensitivity of DLBCLs to chemotherapeutic agents [46], miR-21 might further contribute to chemoresistance by down-regulating the activity of the FOXO1/Bim pathway. Taken together, this study demonstrated that miR-21 may play an oncogenic role in DLBCL by comprehensively regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/FOXO1 pathway (Fig. 4) and that a high miR-21 is associated with a poor prognosis for DLBCL patients. Thus, targeting miR-21 would have therapeutic relevance for the management of DLBCLs. However, further studies using in vivo model would be needed to provide more solid evidence for the oncogenic role of miR-21 in DLBCL.

Moreover, according to previous studies, both miR-17-92 and miR-155 also regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway. MiR-19 is a key oncogenic component of the miR-17-92 cluster, and it suppresses PTEN expression, consistently activates the AKT/mTOR pathway and promotes Myc-induced lymphomagenesis [47]. MiR-155 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway through directly targeting p85α, a negative regulatory subunit of PI3K, in DLBCL [48]. Thus, it is possible that miR-21, miR-17-92, and miR-155 cooperatively contribute to the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in DLBCLs.

In summary, we showed that high miR-21 and miR-17-92 expression had poor prognostic implications in patients with DLBCL. FOXO1 was revealed to be a novel direct target of miR-21. This study demonstrates that miR-21 may play an important oncogenic role in DLBCL through activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway at multiple levels by targeting PTEN and by suppressing the FOXO1/Bim pathway, thus being a potential therapeutic target for DLBCL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples

A total of 200 patients with DLBCL were enrolled in this study. All patients were diagnosed with DLBCL from 1997 to 2010 at Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) according to the current World Health Organization criteria, and FFPE tumor tissues appropriate for miRNA analysis were available. The clinical data were retrieved from the medial records by hemato-oncologists (T.M.K. and D.S.H.). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of SNUH (H-1012-053-344).

Cell lines and reagents

Cell lines derived from GCB-DLBCLs (i.e., OCI-Ly1, OCI-Ly2, SU-DHL4, SU-DHL5, and SU-DHL8) and ABC-DLBCLs (i.e., OCI-Ly10 and SU-DHL9) were kindly provided by Prof. Megan S. Lim (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All of the cell lines were cultured and subtypes in terms of the cell-of-origin according to the instructions of the American Type Culture Collection or the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures. Actinomycin D, LY294002, AS1842856, vinblastine and doxorubicin were all purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

IHC

FFPE tissues were subjected to IHC using primary antibodies as follows: CD10 (56C6, Novocastra, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK), BCL-6 (LN22, Novocastra), MUM1 (MUM1P, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), GCET1 (polyclonal, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), FOXP1 (polyclonal, Abcam), FOXO1 (C29H4, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and Bim (Y36, Abcam) using the Ventana Benchmark XT automated staining system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA). DLBCL cases were immunohistochemically sub-grouped into GCB or ABC phenotypes according to the Choi algorithms, as previously described [49]. FOXO1 expression was evaluated according to the staining intensity (0-3) and location (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic).

qRT-PCR for miRNAs and mRNAs

Total RNA was extracted from the FFPE tissues using a RecoverAllTM Total Nucleic Acid Isolation for FFPE kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The levels of the premature forms of miR-21, the miR-17-92 and miR-155 were determined by qRT-PCR using a one-step SYBRPrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Takara, Seto, Japan) with U6 snRNA (#4373381, Applied Biosystems) as an internal control. The expression levels of the miRNAs were compared with those of 11 normal (i.e., non-neoplastic) tonsils used as controls. The relative expression level (2-ddCt) of each miRNA was calculated as follows: dCt = Ct(miRNA) - Ct(U6); ddCt = dCt(case) - mean dCt(control).

Total RNA was extracted from DLBCL cell lines using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The miR-21 level was evaluated by qRT-PCR using Mir-X miRNA first strand synthesis and SYBR® qRT-PCR kits (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA) with U6 snRNA as an internal control. The expression of p27, p21, FasL, Bim, MDR1, and ABCG2 mRNA in DLBCL cells was evaluated by qRT-PCR using a PrimeScriptTM 1st strand cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) with GAPDH as an internal control. All PCR reactions were performed in triplicate using a Step One Plus thermocycler (Applied Biosystems).

The sequences of the primers used for qRT-PCR for miRNA and mRNA are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

Transfection of miRNA inhibitors or mimics

The cells were placed in six-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) in opti-MEM media (Qiagen, Duesseldorf, Germany) and were transfected with either miR-21 inhibitors or mimics (sequences shown in Supplementary Table S3) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The transfected cells were cultured for 6 hours, and the culture medium was then replaced with fresh complete medium. The cells were harvested at 24 hours after transfection.

Cell viability assay

The cell viability was monitored using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All of the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Reporter gene assay

The pLenti-III-UbC-Luc-FOXO1 3′-untranslated region (UTR) luciferase-reporter construct (Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada) containing many copies of the miR-21 binding motif (5′-AGCUUAU-3′) was co-transfected with miR-21 mimics/inhibitors or negative (i.e., scramble) mimics/inhibitors into DLBCL cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Supplementary Fig. S6A). The Bim promoter luciferase-reporter construct (pGL2 vector) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) containing many copies of the FOXO1 binding motif (5′-GTAAACAA-3′) was co-transfected with a miR-21 inhibitor or negative inhibitor into DLBCL cells (Supplementary Fig. S6B). At 24 hours post-transfection, the cells were lysed, and the supernatant fractions were recovered and the luciferase activities were determined using a luminometer (FB12 luminometer; Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany).

Western blotting

The total cellular protein was extracted using lysis buffer. To obtain cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, the cells were suspended in ice-cold hypotonic buffer and centrifuged. The supernatant contained the cytoplasmic fraction, and the nuclear fraction was extracted from the remnant pellet using high-salt buffer. A total of 10-50 μg of protein was electrophoresed in SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were then incubated with the following antibodies: anti-phospho-AKT, anti-AKT, anti-phospho-p70S6K, and anti-p70S6K antibodies (Cell Signaling); and anti-phospho-FOXO1, anti-FOXO1, anti-Bim, anti-β-actin, and anti-lamin B antibodies (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). The immunoblots were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Drug efflux assay

Drug efflux activity was assessed using a multidrug resistance direct dye efflux kit (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A decrease in the percentage of DiOC2-staining cells determined using FACS Canto II (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) was considered indicative of drug efflux activity.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R 3.0.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The cut-off values for high vs. low expression of each miRNA relative to that of the normal controls (2−ddCt) were selected based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and thereby determined to be 7.9656 for miR-21, 7.5795 for miR-17-92, and 23.1139 for miR-155. The relationships or correlations between the groups were assessed using the χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, Student's t-test, or Pearson's correlation analysis. Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards regression analysis were used for the survival analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL, TABLES AND FIGURES

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program (grant number: NRF-2013R1A1A2013210), and the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) grant (No. 2012-0001190) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST), Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019–5032. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lossos IS, Morgensztern D. Prognostic biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:995–1007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monti S, Savage KJ, Kutok JL, Feuerhake F, Kurtin P, Mihm M, Wu B, Pasqualucci L, Neuberg D, Aguiar RC, Dal Cin P, Ladd C, Pinkus GS, Salles G, Harris NL, Dalla-Favera R, et al. Molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies robust subtypes including one characterized by host inflammatory response. Blood. 2005;105:1851–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenz G, Wright G, Dave SS, Xiao W, Powell J, Zhao H, Xu W, Tan B, Goldschmidt N, Iqbal J, Vose J, Bast M, Fu K, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Armitage JO, et al. Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2313–2323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer AL, 3rd, Young RM, Staudt LM. Pathogenesis of human B cell lymphomas. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:565–610. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young RM, Romesser PB, Kohlhammer H, Lamy L, Zhao H, Yang Y, Xu W, Shaffer AL, Wright G, Xiao W, Powell J, Jiang JK, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;463:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeifer M, Grau M, Lenze D, Wenzel SS, Wolf A, Wollert-Wulf B, Dietze K, Nogai H, Storek B, Madle H, Dorken B, Janz M, Dirnhofer S, Lenz P, Hummel M, Tzankov A, et al. PTEN loss defines a PI3K/AKT pathway-dependent germinal center subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12420–12425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305656110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong JY, Hong ME, Choi MK, Kim YS, Chang W, Maeng CH, Park S, Lee SJ, Do IG, Jo JS, Jung SH, Kim SJ, Ko YH, Kim WS. The impact of activated p-AKT expression on clinical outcomes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 262 cases. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:182–188. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazan-Mamczarz K, Gartenhaus RB. Role of microRNA deregulation in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) Leuk Res. 2013;37:1420–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psathas JN, Doonan PJ, Raman P, Freedman BD, Minn AJ, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. The Myc-miR-17-92 axis amplifies B-cell receptor signaling via inhibition of ITIM proteins: a novel lymphomagenic feed-forward loop. Blood. 2013 doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-473090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagawa H, Ikeda S, Sawada K. Role of microRNA in the pathogenesis of malignant lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:801–809. doi: 10.1111/cas.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jardin F, Figeac M. MicroRNAs in lymphoma, from diagnosis to targeted therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:480–486. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328363def2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrade TA, Evangelista AF, Campos AH, Poles WA, Borges NM, Camillo CM, Soares FA, Vassallo J, Paes RP, Zerbini MC, Scapulatempo C, Alves AC, Young KH, Colleoni GW. A microRNA signature profile in EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11813–11826. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina PP, Nolde M, Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;467:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai H, Wei J, Deng C, Yang X, Wang C, Xu R. MicroRNA-21 regulates the sensitivity of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells to the CHOP chemotherapy regimen. Int J Hematol. 2013;97:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ota A, Tagawa H, Karnan S, Tsuzuki S, Karpas A, Kira S, Yoshida Y, Seto M. Identification and characterization of a novel gene, C13orf25, as a target for 13q31-q32 amplification in malignant lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3087–3095. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao C, Srinivasan L, Calado DP, Patterson HC, Zhang B, Wang J, Henderson JM, Kutok JL, Rajewsky K. Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:405–414. doi: 10.1038/ni1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai D, Kim SW, McKeller MR, Dahia PL, Aguiar RC. Targeting of SMAD5 links microRNA-155 to the TGF-beta pathway and lymphomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3111–3116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910667107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rai D, Karanti S, Jung I, Dahia PL, Aguiar RC. Coordinated expression of microRNA-155 and predicted target genes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;181:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Lee CG. MicroRNA and cancer--focus on apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sansal I, Sellers WR. The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2954–2963. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho KK, Myatt SS, Lam EW. Many forks in the path: cycling with FoxO. Oncogene. 2008;27(16):2300–2311. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calnan DR, Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam EW, Brosens JJ, Gomes AR, Koo CY. Forkhead box proteins: tuning forks for transcriptional harmony. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:482–495. doi: 10.1038/nrc3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X, Gan L, Pan H, Kan D, Majeski M, Adam SA, Unterman TG. Multiple elements regulate nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of FOXO1: characterization of phosphorylation- and 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Biochem J. 2004;378:839–849. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CC, Jeon SM, Bhaskar PT, Nogueira V, Sundararajan D, Tonic I, Park Y, Hay N. FoxOs inhibit mTORC1 and activate Akt by inducing the expression of Sestrin3 and Rictor. Developmental cell. 2010;18:592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay N. Interplay between FOXO, TOR, and Akt. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1813:1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leslie EM, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Multidrug resistance proteins: role of P-glycoprotein, MRP1, MRP2, and BCRP (ABCG2) in tissue defense. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:216–237. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Randle RA, Raguz S, Higgins CF, Yague E. Role of the highly structured 5′-end region of MDR1 mRNA in P-glycoprotein expression. Biochem J. 2007;406:445–455. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alencar AJ, Malumbres R, Kozloski GA, Advani R, Talreja N, Chinichian S, Briones J, Natkunam Y, Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD, Tibshirani R, Lossos IS. MicroRNAs are independent predictors of outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4125–4135. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen W, Wang H, Chen H, Liu S, Lu H, Kong D, Huang X, Kong Q, Lu Z. Clinical significance and detection of microRNA-21 in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Chinese population. Eur J Haematol. 2014;92:407–412. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuchiya Y, Nakajima M, Takagi S, Taniya T, Yokoi T. MicroRNA regulates the expression of human cytochrome P450 1B1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9090–9098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slezak-Prochazka I, Durmus S, Kroesen BJ, van den Berg A. MicroRNAs, macrocontrol: regulation of miRNA processing. RNA. 2010;16:1087–1095. doi: 10.1261/rna.1804410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dengler HS, Baracho GV, Omori SA, Bruckner S, Arden KC, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA, Rickert RC. Distinct functions for the transcription factor Foxo1 at various stages of B cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/ni.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusuf I, Zhu X, Kharas MG, Chen J, Fruman DA. Optimal B-cell proliferation requires phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent inactivation of FOXO transcription factors. Blood. 2004;104:784–787. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie L, Ushmorov A, Leithauser F, Guan H, Steidl C, Farbinger J, Pelzer C, Vogel MJ, Maier HJ, Gascoyne RD, Moller P, Wirth T. FOXO1 is a tumor suppressor in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:3503–3511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-381905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trinh DL, Scott DW, Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, An J, Jones SJ, Mungall AJ, Zhao Y, Schein J, Steidl C, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD, Marra MA. Analysis of FOXO1 mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121:3666–3674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogiatzi P, De Falco G, Claudio PP, Giordano A. How does the human RUNX3 gene induce apoptosis in gastric cancer? Latest data, reflections and reactions. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:371–374. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.4.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haftmann C, Stittrich AB, Sgouroudis E, Matz M, Chang HD, Radbruch A, Mashreghi MF. Lymphocyte signaling: regulation of FoxO transcription factors by microRNAs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1247:46–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mei Y, Wang Z, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Li X, Liu H, Ye J, You H. Regulation of neuroblastoma differentiation by forkhead transcription factors FOXO1/3/4 through the receptor tyrosine kinase PDGFRA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4898–4903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119535109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bogusz AM, Baxter RH, Currie T, Sinha P, Sohani AR, Kutok JL, Rodig SJ. Quantitative immunofluorescence reveals the signature of active B-cell receptor signaling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6122–6135. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kloo B, Nagel D, Pfeifer M, Grau M, Duwel M, Vincendeau M, Dorken B, Lenz P, Lenz G, Krappmann D. Critical role of PI3K signaling for NF-kappaB-dependent survival in a subset of activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:272–277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008969108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng J, Carlson N, Takeyama K, Dal Cin P, Shipp M, Letai A. BH3 profiling identifies three distinct classes of apoptotic blocks to predict response to ABT-737 and conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer cell. 2007;12:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olive V, Bennett MJ, Walker JC, Ma C, Jiang I, Cordon-Cardo C, Li QJ, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, He L. miR-19 is a key oncogenic component of mir-17-92. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2839–2849. doi: 10.1101/gad.1861409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang X, Shen Y, Liu M, Bi C, Jiang C, Iqbal J, McKeithan TW, Chan WC, Ding SJ, Fu K. Quantitative proteomics reveals that miR-155 regulates the PI3K-AKT pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi WW, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Piris MA, Banham AH, Delabie J, Braziel RM, Geng H, Iqbal J, Lenz G, Vose JM, Hans CP, Fu K, Smith LM, Li M, Liu Z, et al. A new immunostain algorithm classifies diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into molecular subtypes with high accuracy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5494–5502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.