Abstract

A two-period, crossover bioavailability study was conducted to evaluate the relative and absolute bioavailability of immediate (IR) and extended-release (XR) lamotrigine formulations under steady-state conditions in elderly patients with epilepsy. On treatment days, each subject's morning dose (IR or XR lamotrigine) was replaced with an intravenous 50 mg dose of stable-labeled lamotrigine. Lamotrigine concentrations were measured at 13 time points between 0 and 96 hours. XR and IR lamotrigine formulations were similar with respect to steady-state area-under-the-concentration-time curve (AUC0-24, ss), average concentration (Cavgss) and trough concentration (Cτss). A 33% lower fluctuation in concentrations with XR was observed relative to IR lamotrigine. The time to peak concentration (Tmaxss) was delayed for XR lamotrigine (3.0 hours vs. 1.3 hours) with lower peak concentration (15% lower). The absolute bioavailability for IR and XR formulations were 73% and 92%, respectively. The formulations were bioequivalent with respect to AUC0-24 h, ss, Cτss, and Cavgss indicating that it may be possible to switch directly from IR to XR lamotrigine without changes in the total daily dose.

Keywords: lamotrigine, elderly, stable isotope, immediate-release, extended-release

INTRODUCTION

The pharmacokinetics of medications may be altered with age.1, 2 For example, changes in gastrointestinal physiology have the potential to influence drug absorption.3, 4 The pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine with immediate release formulation (IR) are well characterized in adult patients with epilepsy; however, there is very limited information available for IR lamotrigine or extended-release (XR) formulation of lamotrigine in elderly patients. In general, extended-release formulations reduce peak-to-trough fluctuation, and may have an improved adverse effect profile and compliance in comparison to immediate release formulations.5 The XR lamotrigine is an enteric coated tablet; formulated by a modified release eroding matrix core (DiffCORE) that reduces the dissolution rate of lamotrigine compared to IR lamotrigine and prolongs drug release over approximately 12 to 15 hours.6 The steady-state pharmacokinetics following administration of the XR lamotrigine compared to IR lamotrigine have been studied in subjects (18-88 years) with epilepsy in an open-label crossover study.7 In a neutral metabolism group (with no concomitant inducers or inhibitors), the steady-state area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 hours (AUC0-24, ss) of lamotrigine in subjects receiving XR lamotrigine was 138 ug-h/mL compared to 142 ug-h/mL when subjects were taking IR lamotrigine. Steady-state peak concentration (Cmax,ss) values of serum lamotrigine are, on average, 12.7% lower (geometric mean: 6.83 [XR lamotrigine] vs. 7.82 [IR lamotrigine] μg/mL). The fluctuation index was reduced by 37% (geometric mean: 0.34 [XR lamotrigine] vs. 0.55 [IR lamotrigine]). Tmax increased from 1.5 to 6 hours after switching from IR to XR lamotrigine. The study demonstrated comparable bioequivalence between the IR and XR formulations in terms of AUC0-24, ss and Cτss.7 Detailed information on the pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability of IR or XR lamotrigine in elderly subjects has not been published.

Stable-labeled (non-radioactive) isotope drug formulations are effective probes for pharmacokinetic and bioavailability studies.8 Stable isotope methodology permits the simultaneous administration of a drug by two routes as well as by two formulations depending on the availability of the labeled compounds. The creation of a stable labeled intravenous lamotrigine formulation 9 also enables detailed characterization of the pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine while patients are at steady state. Subsequently, characterization of absolute and relative bioavailability during a single occasion can be done under steady-state conditions without disrupting maintenance therapy. Furthermore, determination of clearance, volume of distribution, and half-life can also be determined under steady-state conditions. The objective of this pilot study was to evaluate relative and absolute oral bioavailability of two formulations (IR and XR) of lamotrigine under steady-state conditions in elderly patients with epilepsy.

METHODS

This was a classic two-period, crossover bioavailability study in elderly patients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committees at the University of Miami and the University of Minnesota. Consent to participate was obtained from all subjects.

Study subjects

The subjects (n=12) were elderly epilepsy patients >60 years of age. Inclusion criteria were: a stable maintenance IR lamotrigine regimen for at least 2 weeks, the ability to ingest oral medication, and in good general health as confirmed by medical history and physical examination. Exclusion criteria were: a significant unstable medical or psychiatric disorder, a known history of active drug or alcohol abuse, donation of blood within 60 days prior to the study, chronic anemia, or use of drugs that could significantly affect the metabolism and clearance of lamotrigine (e.g., Hepatic enzyme inducers: carbamazepine, ethosuximide, hormone replacement therapy (estrogens), oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, rifampin, rifapentine, St. John's wort; Hepatic enzyme inhibitors: valproic acid, tamoxifen). Although individuals with designated guardians were allowed to enter the study, all subjects were screened by a physician and deemed to be able to self consent. Subjects were admitted to the Infusion Center at the University of Miami. Vital signs and an EKG rhythm strip were obtained before, during, and 15 minutes after intravenous (i.v.) infusion of the stable labeled formulation.

Study formulations

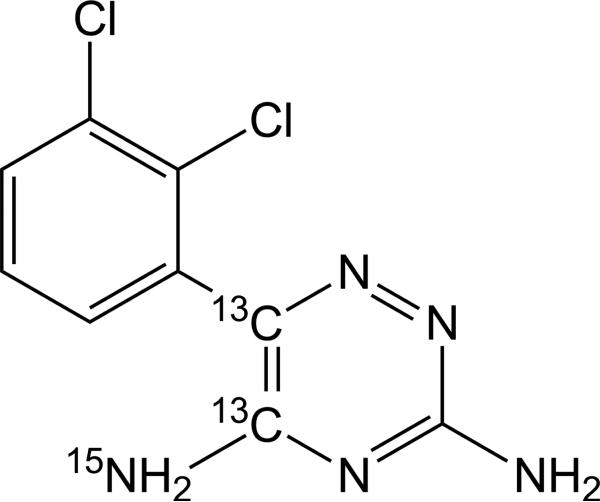

The oral formulations, IR lamotrigine (LAMICTAL®) and XR lamotrigine (LAMICTAL® XRTM), were donated from GlaxoSmithKline, USA. The stable isotope form of lamotrigine (13C2, 15N-lamotrigine; shown in Figure 1) was synthesized by Cambridge Isotopes (Andover, MA, USA). The stable-labeled lamotrigine was formulated for i.v. administration in a 30% w/v 2- hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) solution to make a final strength of 10 mg/mL by the Pharmaceutics Division at the University of Iowa. Stable-labeled lamotrigine was dispensed in 5 mL vials (IND 72,642). The formulation was diluted with normal saline to a final volume of 15 mL before being infused to patients at a rate of 1 mL/min. The intravenous infusion of stable-labeled lamotrigine to patients has been demonstrated to be well tolerated with no adverse experiences and no changes in vital signs.9 No clinically significant changes in laboratory parameters and physical examinations occurred during the treatment phases.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of SL lamotrigine ([13C2, 15N]- 3, 5 diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine).

Study design

Subjects were already on chronic IR lamotrigine therapy; therefore, all subjects received IR lamotrigine in the first treatment phase (IR phase) in order to minimize interruptions in therapy. After completion of sample collection in the IR phase, patients were switched to XR lamotrigine for a minimum of one week before being started with XR treatment phase. On both IR and XR study days (day 1 of each phase), a 50 mg replacement stable labeled dose of lamotrigine was administered intravenously along with remaining oral lamotrigine dose (unlabeled). Food was withheld for approximately 8 hours before oral dosing and withheld until 1.5 hours post-dose. Subjects maintained their total daily dose of lamotrigine over both treatment phases of the study. Blood samples for pharmacokinetic analysis were collected prior to administration (pre-dose) of lamotrigine (oral and i.v. lamotrigine) and at 5 minutes, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours post-dose. The samples were immediately centrifuged and plasma was transferred to separate containers for storage at −80°C until analysis.

Lamotrigine analysis

Plasma samples (500 μL each) for measurement of unlabeled lamotrigine and stable-labeled lamotrigine concentrations were simultaneously determined by a validated gas chromatography– mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method. After extraction and derivatization with tert-butyl dimethyl silyl chloride, the samples were injected onto a J&W DB-5ms column (30 m x 0.25mm i.d, J&W Scientific, ChromTech, Apple Valley, MN) with detection on an Agilent 6890 series GC system in selected ion mode at the following mass to charge ratios (m/z): internal standard (m/z = 388); unlabeled lamotrigine (m/z = 426 [M-71]); and labeled lamotrigine (m/z = 431 [M-71]). A standard curve ranging from 0.25 to 20 μg/mL in unlabeled lamotrigine concentrations and 0.025 to 2 μg/mL in stable-labeled lamotrigine concentrations was established. Quality controls (QCs) for lamotrigine were 0.75 (low), 7.5 (medium) and 16 μg/mL (high) and for stable-labeled lamotrigine were 0.075 (low), 0.75 (medium) and 1.6 μg/mL (high). QCs were run in triplicate with each batch of subject samples. Values of QC samples were considered acceptable if the accuracy (%bias) was within ±15% and precision (%CV ) was <15%.10

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analysis

Oral pharmacokinetics

Individual subject plasma concentration-time data of oral lamotrigine (unlabeled) were subjected to non-compartmental analysis (NCA). The pharmacokinetic analyses were performed with Pheonix™ WinNonlin version 6.1 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). The following steady state pharmacokinetic parameters were determined for each subject who were either on oral IR or XR lamotrigine: steady-state area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 hours (AUC0-24, ss), maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmaxss), lowest observed concentration (Cminss), average plasma concentration (Cavgss), trough concentration (Cτss), time to maximum concentration (Tmaxss), and fluctuation index, derived as [Cmaxss – Cminss] × 100/Cavgss. Summary statistics (arithmetic and geometric mean, 95% confidence interval [CI], between-subject coefficient of variation [%CVb], standard deviation, median, and range) were calculated by regimen (XR or IR lamotrigine) for all pharmacokinetic end points. Summary data included geometric mean with its 95% CI and %CVb for all the pharmacokinetic parameters, except for Tmaxss. For Tmaxss, median and range were used.

Relative bioavailability (XR lamotrigine vs. IR lamotrigine)

To assess the relative bioavailability of XR lamotrigine compared to IR lamotrigine, a dose-normalized statistical analysis was performed for the pharmacokinetic parameters: AUC0-24, ss, Cmaxss, Cτss, Cavgss, and fluctuation index. These parameters were dose normalized and loge transformed (except the fluctuation index) in order to fit a mixed model separately for each end point, with subject as a random component, to account for the within-subject variability of the measurements. The relative bioavailability of XR lamotrigine to IR lamotrigine was assessed by utilizing the 90% CIs.11

Intravenous pharmacokinetics

Individual subject plasma concentration-time data of i.v. SL lamotrigine were also subjected to NCA. The following single dose i.v. pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated for each subject by treatment phase: area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to t (AUC0-t), area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to infinity (AUC0-∞), first-order elimination rate constant (ke), elimination half-life (t1/2), clearance (CL), and volume of distribution (Vz). ke was determined from the slope of the terminal log-linear portion of the concentration-time curve, and t1/2 was calculated as ln2/ ke. AUC0-t was calculated according to the linear trapezoidal rule from time 0 to the time of last quantifiable concentration after drug administration. AUC0-∞ was calculated as AUC0-t + Ct/ ke where Ct is the last quantifiable pharmacokinetic concentration. All pharmacokinetic parameters were summarized by descriptive statistics such as arithmetic means with standard deviations, geometric means with their 95% CIs, and %CVb so the results could be interpreted in relation to both normal distribution and a log normal distribution.

Absolute bioavailability

The percent absolute bioavailability (%Fabs) of IR and XR formulations was calculated by the following equation and the results were presented as arithmetic mean with its standard deviation.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bioequivalence statistics were obtained from Pheonix™ WinNonlin version 6.1 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). A paired t test comparison with the R statistics software version 2.10.1 (R Development Core Team, 2009) was performed for comparisons of %Fabs between IR and XR formulations and CL of stable-labeled lamotrigine after IR and XR treatment phases. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Subjects

Twelve elderly patients (7 female, 5 male) with epilepsy (71.3 ± 7.6 years; range: 63-87 years) were enrolled and completed the study. The majority of subjects (n=8) were non-Hispanic whites (67%). Patients were on a median daily dose of 250 mg of IR lamotrigine (range: 200-700 mg). Six patients were on daily doses of 200 mg. Ten patients were on a once daily dosing regimen with the remaining two patients receiving lamotrigine twice daily. All subjects completed both phases of the study. Heart rate, pulse, blood pressure, and nystagmus were not remarkable following intravenous infusion of lamotrigine. EKG was normal. The safety of intravenous stable labelled lamotrigine in younger individuals has been published by our group.9

Oral pharmacokinetics

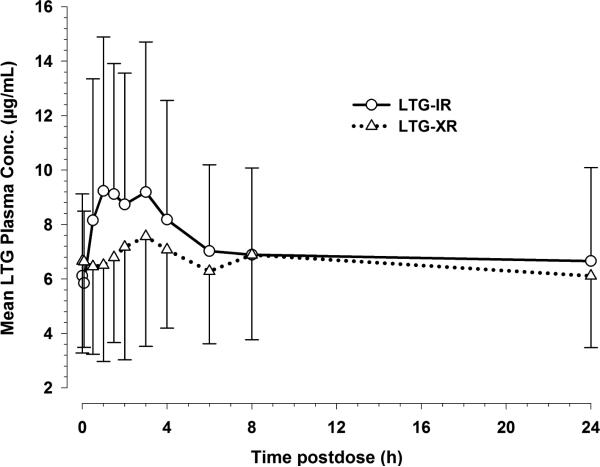

The dose normalized mean concentrations of lamotrigine in plasma (normalized to 200 mg dose) and their fluctuation window over a 24 hour dosing interval were markedly lower following administration of the XR lamotrigine formulation compared to the IR lamotrigine formulation 12 (Figure 2). Morning trough concentrations of lamotrigine on the study day following XR lamotrigine administration for a minimum of one week were comparable to morning trough concentrations following IR lamotrigine administration (Figure 2). This observation suggests that the lamotrigine concentrations following XR lamotrigine administration had reached steady-state within one week.

Figure 2. Mean plasma lamotrigine concentration vs. time profiles following the administration of IR lamotrigine and XR lamotrigine formulations under steady-state conditions. The plasma concentrations were dose normalized to 200 mg lamotrigine dose.

Data are shown as mean with standard deviation (upper or lower error bar) for 12 subjects on IR and XR lamotrigine.

A summary of steady-state oral pharmacokinetic parameters (including their dose-normalized parameter values) for both the formulations are presented in Table 1. Cmaxss was lower in the XR treatment phase (geometric mean: 7.9 μg/mL), relative to the IR treatment phase (geometric mean: 9.4 μg/mL). Following the administration of IR lamotrigine, the median Tmaxss was 1.3 hours post-dose, whereas after XR lamotrigine administration Tmaxss was extended to 3 hours post-dose. The degree of fluctuation at steady state was considerably lower with XR lamotrigine relative to IR lamotrigine (49% vs. 73% ). Other pharmacokinetic parameters such as AUC0-24 h, ss, Cminss, Cavgss, and Cτss values were similar for both the treatment phases. There was a large between- subject variability for each steady-state pharmacokinetic parameter. This could be partly attributed to the wide range of lamotrigine maintenance doses that subjects were receiving in the study.

Table 1.

Summary of plasma LTG steady-state pharmacokinetic parameters of LTG-IR and LTG-XR formulations

| Pharmacokinetic parameter (units)a | LTG-IR (n=12) | LTG-XR (n=12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | %CVb | Geometric mean (95% CI) | %CVb | |

| AUC0-24 h, ss (μg.h/mL) | 142.8 (92.4, 220.7) | 67.9 | 132.3 (88.1, 198.8) | 54.4 |

| Cmaxss (μg/mL) | 9.36 (6.14, 14.8) | 57.3 | 7.93 (5.01, 12.5) | 51.6 |

| Cminss (μg/mL) | 4.41 (2.82, 6.90) | 62.6 | 4.81 (3.03, 7.63) | 59.2 |

| Cavgss (μg/mL) | 6.50 (4.25, 9.96) | 59.8 | 6.13 (3.95, 9.53) | 55.7 |

| Cτss (μg/mL) | 5.50 (3.29, 9.21) | 61.8 | 5.58 (3.64, 8.54) | 56.2 |

| Fluctuation index (%) | 73.0 (60.1, 88.6) | 34.1 | 48.8 (40.2, 59.3) | 28.0 |

| Tmaxss (h)b | 1.43 (0.00 - 4.00) | 2.79 (0.00 - 8.00) | ||

| Absolute bioavailability (%Fabs)c* | 73.12 ± 16.26 | 91.72 ± 28.08 | ||

|

Pharmacokinetic parameters normalized to 200 mg daily dose | ||||

| AUC0-24 h, ss, norm(μg.h/mL) | 112.4 (79.3, 159.2) | 43.9 | 104.15 (75.48, 143.71) | 34.9 |

| Cmaxss, norm (μg/mL) | 7.36 (5.22, 10.39) | 41.0 | 6.24 (4.16, 9.36) | 44.7 |

| Cminss, norm (μg/mL) | 3.47 (2.34, 5.15) | 44.8 | 3.78 (2.55, 5.61) | 43.3 |

| Cavgss, norm (μg/mL) | 5.12 (3.63, 7.22) | 37.9 | 4.83 (3.32, 7.01) | 43.9 |

| Cτss, norm (μg/mL) | 3.90 (2.22, 6.86) | 68.8 | 4.87 (3.29, 7.22) | 59.2 |

Parameters are derived from 24 hour interval data following LTG administration on the study day of each treatment phase with the exception of two subjects, for whom 12 hour interval data are considered as they were on twice-daily dosing regimen

Tmaxss is presented as geometric mean (n=11) and range

Absolute bioavailability is presented as mean ± SD

p = 0.09

Relative and absolute bioavailability

The relative bioavailability of XR lamotrigine compared to IR lamotrigine is summarized in Table 2. Based on the geometric least squares XR to IR mean ratios and their 90% confidence intervals (CI), XR lamotrigine is similar to IR lamotrigine with respect to the pharmacokinetic parameters, AUC0-24 h, ss, Cτss, and Cavgss. However, Cmaxss of XR lamotrigine was on average 15% lower than for IR lamotrigine with 90% CI between 2% and 27% (Table 2). This could be explained by the expected lower degree of fluctuation (33% lower with 90% CI 21-43%) for XR lamotrigine relative to IR lamotrigine. The fluctuation index (37% lower with 90% CI 24-47%) for XR lamotrigine was slightly improved when considering only the subjects (n=10) who were on a once daily dosing schedule. Cavgss for XR lamotrigine was similar to IR lamotrigine (101% with 90% CI between 86% and 119%). Simultaneous administration of i.v. SL lamotrigine with oral lamotrigine allowed determination of the %Fabs, which was calculated to be 73% for IR lamotrigine and 92% for XR lamotrigine.

Table 2.

Summary of relative bioavailability statistical analysis (n=12; 90% CI criterion: 80-125%) of dose-normalized steady state LTG pharmacokinetic parameters (XR vs. IR)

| Pharmacokinetic parameter | Geometric least squares XR to IR mean ratio (%) | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|

| AUC0-24 h, ss | 92.7 | (81.2, 105.7) |

| Cmaxss | 84.7 | (73.2, 98.1) |

| Cτss | 101.3 | (86.4, 118.9) |

| Cavgss | 94.4 | (83.4, 106.7) |

| Fluctuation indexa | 66.9 | (56.8, 78.9) |

fluctuation index is not a dose-normalized metric

Stable-labeled Lamotrigine pharmacokinetics During IR and XR lamotrigine Treatment Phases

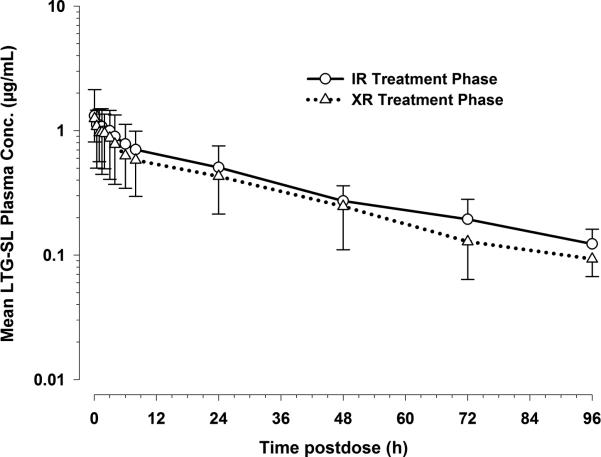

The log-linear plot of mean plasma stable-labeled lamotrigine concentrations versus time profiles following i.v. administration on IR and XR treatment phases were visually comparable (Figure 3). The only noticeable difference was the lower exposure of stable-labeled lamotrigine during XR treatment phase relative to the exposure on IR treatment phase. However, the terminal phases of SL lamotrigine on both the treatment phases were parallel to each other. Table 3 summarizes the pharmacokinetic parameters determined following i.v. administration of stable-labeled lamotrigine on each treatment phase. The pharmacokinetic data for the stable-isotope i.v. formulation allowed us to characterize the CL and Vd of lamotrigine in elderly patients. Overall, the parameters were comparable between the two treatment phases with the exception of CL, which was, on average, higher for XR treatment phase when compared to IR treatment phase (1.4 ± 0.8 vs. 2.0 ± 1.5; p-value: 0.03). This could be partly due to more than a two-fold difference in CL between the two treatment phases for one of the subjects in the study. The geometric mean t1/2 was 35.9 hours and 30.4 hours on IR and XR treatment phases, respectively. Geometric mean Vz was 66 liters and 74 liters on IR and XR treatment phases, respectively. There was considerable between-subject variability in the pharmacokinetic parameter values (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Mean plasma concentration vs. time post-dose profiles following i.v. administration of stable labeled lamotrigine on IR and XR treatment phases (log-linear plot). Data are shown as mean with standard deviation (upper or lower error bar) for 12 subjects on IR and XR treatment phases.

Table 3.

Summary of stable isotope labeled LTG (LTG-SL) pharmacokinetic parameters after intravenous administration on IR and XR treatment phases

| Pharmacokinetic parameter (units) | IR treatment phase (n=12) | XR treatment phase (n=12) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Geometric mean (95% CI) | %CVb | Mean ± SD | Geometric mean (95% CI) | %CVb | |

| AUCo-t (μg.h/mL) | 35.7 ± 14.1 | 32.5 (23.7, 44.6) | 39.50 | 29.6 ± 13.9 | 25.37 (16.8, 38.3) | 47.0 |

| AUC0-∞ (μg.h/mL) | 42.5 ± 15.1 | 39.32 (29.7, 52.1) | 35.60 | 33.5 ± 14.5 | 29.52 (20.4, 42.7) | 43.3 |

| ke(1/h) | 0.020 ± 0.006 | 0.019 (0.015, 0.024) | 28.80 | 0.024 ± 0.006 | 0.023 (0.019, 0.027) | 27.3 |

| t1/2 (h) | 38.3 ± 16.3 | 35.92 (28.7, 45.0) | 42.60 | 31.6 ± 9.47 | 30.36 (25.3, 36.4) | 30.0 |

| CL (L/h)* | 1.41 ± 0.79 | 1.27 (0.96, 1.68) | 55.80 | 2.03 ± 1.47 | 1.69 (1.17, 2.45) | 72.2 |

| Vz (L) | 77.9 ± 52.6 | 65.89 (45.7, 95.0) | 67.50 | 96.6 ± 94.0 | 74.2 (48.2, 114.3) | 97.4 |

p = 0.03

DISCUSSION

The steady-state pharmacokinetics of IR and XR lamotrigine formulations were evaluated in this classic two-period, crossover bioavailability study. This is the first report of the absolute bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of IR lamotrigine and XR lamotrigine using a stable-labeled isotope, intravenous lamotrigine formulation in elderly subjects with epilepsy. In this elderly group of patients, comparable dose-normalized relative bioavailability between IR and XR formulations in terms of AUC0-24 h, ss, Cτss, and Cavgss, were observed (see Table 1), although variability was large. These results are in close agreement with previous results that demonstrate comparable bioequivalence of IR lamotrigine and XR lamotrigine in patients with a median age of 38.5 years (range: 18 to 88 years).7 The absolute bioavailability of lamotrigine from the XR formulation in that study tended to be higher compared to the IR formulation; however, the values were not statistically different (IR: 73% ± 16% vs. XR: 92% ± 28%, p-value: 0.09). Steady-state concentrations fluctuated less with the XR lamotrigine relative to IR lamotrigine. This has been found to be a major advantage of the extended-release preparations of AEDs.13 A smaller fluctuation between peak and trough concentrations with XR lamotrigine may improve tolerability and seizure control.7 Nevertheless, lamotrigine has a long terminal half-life (mean of 32-38 hr in this study) and fluctuations between peak and trough for IR lamotrigine are not large. Prescribers may wish to consider cost differences between generic products and XR Lamictal® and select the XR dosing form for patients with higher apparent oral clearances. It should be noted that the sample size in this study is small and interacting drugs were excluded. The XR formulation may be desirable in patients with shorter half-lives or when greater differences in the fluctuation between peak and trough concentrations would be expected (e.g., in elderly patients on inducers of lamotrigine glucuronidation such as carbamazepine and phenytoin.14, 15 Lamotrigine is primarily glucuronidated by UGT1A4 and this pathway accounts for 80-90% of the excreted dose in urine.16

The pharmacokinetics of IR lamotrigine in elderly patients were highly variable (CV = 44% for dose-normalized AUC). The variability is in agreement with the variability observed in a previous study.7 A previous study demonstrated increased peak concentration (25%) and exposure (55%), an extended half-life (6.3 hour longer), and reduced apparent oral clearance (35%) in elderly healthy volunteers.17 In contrast, two separate lamotrigine population pharmacokinetic studies showed no effect of age on apparent oral clearance in elderly patients; however, these studies included adult populations with few elderly subjects.18,19 The reported oral clearance observed in a larger population pharmacokinetic study in elderly epilepsy patients was not different among the older age groups.14 In the Punyawudho et al. study20, only elderly patients were included in the analysis, and therefore a comparison to younger and older patients could not be made. In vitro studies in human liver microsomes prepared from livers obtained from younger and elderly donors also showed no significant difference in intrinsic clearance (Vmax/Km).16 As expected, a slower absorption rate for the XR formulation was observed compared to the IR formulation. This was apparent both visually (Figure 2) and quantitatively from the longer time taken to attain Cmaxss and resultant lower observed Cmaxss.

Application of stable isotope methodology to relative bioavailability studies is an elegant method for simultaneously determining absolute bioavailability as well as other pharmacokinetic parameters in patients without interrupting maintenance therapy.8 Stable isotope methodology reduces intra-patient and intra-assay variability by allowing simultaneous measurement of unlabeled and labeled drug concentrations (i.e., from the same blood sample).15 This methodology was successfully utilized to determine the pharmacokinetics of several other AEDs: phenytoin 22, carbamazepine 16, topiramate 24 and valproic acid 17, 18. The stable isotope methodology allowed us to determine relative bioavailability (XR vs. IR), absolute bioavailability, clearance, volume of distribution, and half-life in a classic-crossover design and without disrupting chronic lamotrigine monotherapy of elderly patients. A significant difference in clearance was observed between IR and XR treatment phases (1.4 ± 0.8 vs. 2.0 ± 1.5; p-value: 0.03) after the administration of stable-labeled lamotrigine. The mechanism for this difference is not clear, but is unlikely to be due to saturation of UGT1A4 because the reported Km values (mean 1.2 mM, range 0.7-5.6 mM ) for lamotrigine N-glucuronidation in a bank of human liver microsomes (Km = 1.56 mM with cloned, expressed UGT1A4)27 is an order of magnitude higher than the lamotrigine therapeutic concentration range.16 In that in vitro study, there was no difference in the intrinsic clearance between microsomes obtained from younger adult or elderly donors (n=18 in each group). After the stable-labeled lamotrigine administration in both the IR and XR treatment phases, the mean half-life was 32-38 hours, exceeding the range of 24-30 hours reported for normal volunteers28 and may reflect a modest difference in clearance or volume of distribution due to age.1, 2 The age-related hypothesis is supported by previous studies that revealed age-related differences in lamotrigine pharmacokinetics: 20 to 35% lower clearance and 6.3 hour longer half-life in elderly compared to younger adults.19, 20

We observed lower absolute bioavailability (73% ± 16%) following IR lamotrigine administration in elderly patients with epilepsy compared to previously reported absolute bioavailability (97.6% ± 4.8%) following 75 mg of lamotrigine in a gelatin capsule formulation in healthy, adult volunteers compared to intravenous administration of lamotrigine isethionate.30 This could be related to formulation differences between the studies and possibly, reduced absorptive capacity in the elderly compared to younger adults.3, 4 Lamictal® IR tablets reportedly have a bioavailability of 98%.12 As this was a crossover design in patients who were already taking the IR formulation for clinical care, all patients were given the XR formulation in the second treatment. It is possible that a treatment effect due to the fixed sequence was introduced.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the potential benefit of XR lamotrigine to improve tolerability and seizure control by the lower fluctuation of steady-state concentrations compared to IR lamotrigine. We demonstrated that elderly patients with epilepsy may be switched directly from IR lamotrigine to XR lamotrigine without changing the total daily dose while maintaining overall systemic exposure and comparable steady-state average and steady-state trough concentrations. A longer half-life was observed in these elderly patients compared to younger healthy volunteers. Additional studies are needed to determine if aging affects lamotrigine clearance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eric Larson for his contribution in developing simultaneous assay for the determination of unlabeled and stable labeled lamotrigine. This project was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health NINDS NS16308, R01AG026390 and GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Brundage holds stock from GlaxoSmithKline. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hammerlein A, Derendorf H, Lowenthal DT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in the elderly. Clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;35:49–64. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199835010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:163–84. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gidal BE. Drug absorption in the elderly: biopharmaceutical considerations for the antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Res. 2006;68(Suppl 1):S65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsay RE, Cloyd JC, Kelly KM, Leppik IE, Perucca E. The Neurobiology of Epilepsy and Aging. Academic Press; San Diego: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werz MA. Pharmacotherapeutics of epilepsy: use of lamotrigine and expectations for lamotrigine extended release. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:1035–46. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaxo-SmithKline. Research Triangle Park: 2011. Lamictal®XR™ (package insert). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tompson DJ, Ali I, Oliver-Willwong R, et al. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine when converting from a twice-daily immediate-release to a once-daily extended-release formulation in subjects with epilepsy (The COMPASS Study). Epilepsia. 2008;49:410–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baillie TA. The use of stable isotopes in pharmacological research. Pharmacol Rev. 1981;33:81–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conway JM, Birnbaum AK, Leppik IE, et al. Safety of an intravenous formulation of lamotrigine. Seizure. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. Rockville: 2001. Bioanalytical method validation. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Rockville: Mar, 2003. Guidance for Industry: Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Studies for Orally Administered Drug Products - General Considerations. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaxo-SmithKline. Research Triangle Park: 2011. Lamictal® (package insert). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppik IE, Hovinga CA. Extended-release antiepileptic drugs: a comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters relative to original immediate-release formulations. Epilepsia. 2012;54:28–35. doi: 10.1111/epi.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Punyawudho B, Ramsay RE, Macias FM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine in elderly patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:455–63. doi: 10.1177/0091270007313391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy PJ, Sullivan HR. Stable isotopes in pharmacokinetic studies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:609–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.003141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marino SE, Birnbaum AK, Leppik IE, et al. Steady-state carbamazepine pharmacokinetics following oral and stable-labeled intravenous administration in epilepsy patients: effects of race and sex. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:483–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann F, von Unruh GE, Jancik BC. Valproic acid disposition in epileptic patients during combined antiepileptic maintenance therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;19:383–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00544590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Unruh GE, Jancik BC, Hoffman F. Determination of valproic acid kinetics in patients during maintenance therapy using a tetradeuterated form of the drug. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1980;7:164–7. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200070406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arif H, Svoronos A, Resor SR, Jr., Buchsbaum R, Hirsch LJ. The effect of age and comedication on lamotrigine clearance, tolerability, and efficacy. Epilepsia. 52:1905–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posner J, Holdich TA, Crome P. Comparison of lamotrigine pharmacokinetics in young and elderly healthy volunteers. J Pharm Med. 1991;1:121–8. [Google Scholar]