Abstract

Importance

The U.S. Army suicide attempt rate increased sharply during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Comprehensive research on this important health outcome has been hampered by a lack of integration among Army administrative data systems.

Objective

To identify risk factors for Regular Army suicide attempts during the years 2004–2009 using data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS).

Design, Setting, and Participants

There were 9,791 medically documented suicide attempts among Regular Army soldiers during the study period. Individual-level person-month records from Army and Department of Defense administrative data systems were analyzed to identify socio-demographic, service-related, and mental health risk factors distinguishing suicide attempt cases from an equal-probability control sample of 183,826 person-months.

Main Outcome and Measures

Suicide attempts were identified using Department of Defense Suicide Event Report records and ICD-9 E95x diagnostic codes. Predictor variables were constructed from Army personnel and medical records.

Results

Enlisted soldiers accounted for 98.6% of all suicide attempts, with an overall rate of 377/100,000 person-years, versus 27.9/100,000 person-years for officers. Significant multivariate predictors among enlisted soldiers included socio-demographic characteristics (female gender, older age at Army entry, younger current age, low education, non-hispanic white), short length of service, never or previously deployed, and the presence and recency of mental health diagnoses. Among officers, only socio-demographic characteristics (female gender, older age at Army entry, younger current age, and low education) and the presence and recency of mental health diagnoses were significant.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results represent the most comprehensive accounting of U.S. Army suicide attempts to date and reveal unique risk profiles for enlisted soldiers and officers, and highlighting the importance of focusing research and prevention efforts on enlisted soldiers in their first tour of duty.

Rates of U.S. Army suicide attempts rose sharply during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq,1 in parallel with the trend in suicide deaths.2–4 Our understanding of suicide attempts in this population remains limited, including which soldiers are at greatest risk. Self-report data from recent survey studies are informative5–8 but may not correspond with actual medical encounters, which are particularly important due to their impact on the Army health care system. The few studies examining medically documented attempts are limited in that they rely on a single Army or Department of Defense (DoD) database to identify cases.9,10 Recent evidence suggests that a comprehensive examination of Army suicide attempts requires integration of multiple administrative data systems.1

The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS; www.armystarrs.org) was designed to identify risk and protective factors for suicidal events in order to inform evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies.11,12 The Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) is an Army STARRS component that integrates a wide range of Army/DoD administrative data systems, including every system in which suicidal events are medically documented. Through this integration the HADS provides the most comprehensive database of U.S. Army suicide attempts ever assembled. Herein, we examine HADS data to identify segments of the Army population at greatest risk of suicide attempt through multivariate analyses of socio-demographic, service-related, and mental health risk factors.

METHODS

Sample

The 38 Army/DoD administrative data systems in the HADS include individual-levelrecords for all soldiers on active duty between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 (n = 1.66 million).12 During this time, there were 9,791 unique soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (cases) among 37.0 million Regular Army person-months (n = 975,057 total soldiers, excluding U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve). We selected an equal-probability control sample of 183,826 person-months, exclusive of soldiers with a record indicating suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal outcome (e.g., suicidal ideation)1 and person-months in which a soldier died due to suicide, combat, homicide, injury, or illness. The control sample was generated by selecting every 200th person-month after stratifying HADS records by number of months in service, deployment status (never, currently, and previously deployed), gender, and rank. The full case-control analytic sample contained 193,617 person-months, with each control person-month assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months without a suicide attempt.

Measures

The 9,791 suicide attempt cases were identified based on Army/DoD administrative records from: the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER),13 a DoD-wide surveillance mechanism that aggregates information on suicidal behaviors via a standardized form completed by medical providers at DoD treatment facilities (n = 3,594 cases); and ICD-9-CM E95x diagnostic codes (E950–E958; indicating self-inflicted poisoning or injury with suicidal intent) from the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR), Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS), and TRANSCOM (Transportation Command) Regulating and Command and Control Evacuating System (TRAC2ES), which together provide healthcare encounter information from military and civilian treatment facilities, combat operations, and aeromedical evacuations (n = 6,197 cases). The E959 code was excluded, as it is used to indicate late effects of a self-inflicted injury. For soldiers with multiple suicide attempts, we selected the first attempt using a hierarchical classification scheme that prioritized DoDSER records due to that system’s more extensive reporting requirements1. Socio-demographic variables, length of service, deployment status, and mental health diagnosis variables were also drawn from Army/DoD administrative data systems (see eTable 1, available online at www.armystarrs.org/publications). An indicator variable for previous mental health diagnosis during Army service combined categories derived from ICD-9-CM codes (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, personality disorders), excluding postconcussion syndrome and tobacco use disorder when those were the only recorded mental health diagnoses (see eTable 2). Among soldiers with a history of mental health diagnosis, recency of diagnosis was based on the number of months elapsed between their most recent diagnostic record and their suicide attempt (cases) or sampled person-month record (controls).

Analysis methods

Risk factors for suicide attempt were examined separately among enlisted soldiers (n = 163,178 person-months) and officers (n = 30,439 person-months; including warrant officers). Logistic regression analyses examined multivariate associations of socio-demographic characteristics with suicide attempts (gender, age at entry into Army service, current age, race, education, and marital status), followed by separate models evaluating incremental predictive effects of length of service (1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5–10 years, greater than 10 years), deployment status (never deployed, currently deployed, previously deployed), and presence/recency of mental health diagnoses (no diagnosis vs. 1 month, 2–3 months, 4–12 months, and 13+ months since most recent diagnosis). Logistic regression coefficients were exponentiated to obtain odds-ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Final model coefficients were used to generate standardized estimates of risk14 (number of suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) for each category of each predictor under the model assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means. Based on previous work indicating that the Army suicide attempt rate increased over the 2004–2009 study period,1 a separate dummy predictor variable was included in each logistic regression equation to control for calendar month and year. Coefficients of other predictors can consequently be interpreted as averaged within-month associations based on the assumption that effects of other predictors do not vary over time.

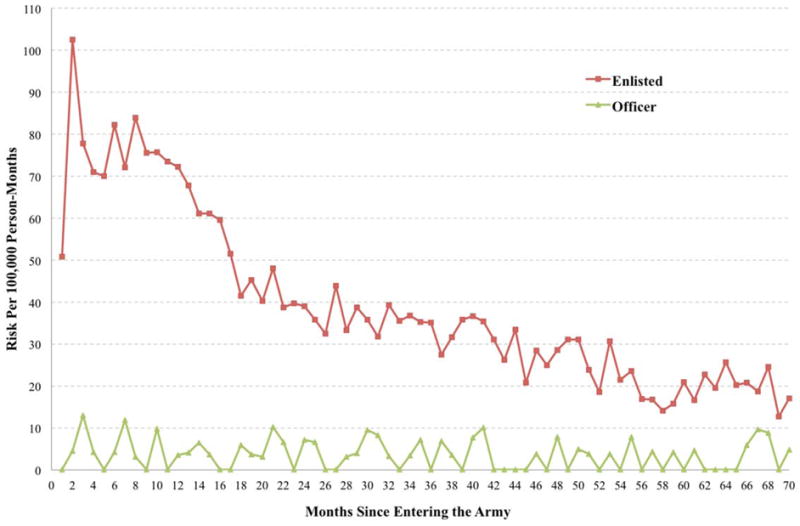

To further examine associations between length of service and risk of suicide attempt, we generated separate discrete-time hazard functions for enlisted soldiers and officers. These hazard functions were used to estimate risk of suicide attempt in each month since entering Army service (suicide attempts per 100,000 person-months).

RESULTS

Enlisted soldiers comprised 83.5% of Regular Army soldiers in the HADS database and accounted for 98.6% of all suicide attempt cases (n = 9,650), with an overall rate of 377/100,000 person-years during the 2004–2009 study period. Officers (including commissioned and warrant officers) made up 16.5% of the Regular Army and accounted for 1.4% of cases (n = 141), with an overall rate of 27.9/100,000 person-years (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1.

Enlisted Soldiers: Multivariate Associations of Socio-demographic Characteristics with Suicide Attempts in the Army STARRS 2004–2009 Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) Sample (n = 163,178).1

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)2 | Rate3 | Pop %4 | SR5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 1.0 | – | 7,214 | 26,507,814 | 326.6 | 86.3 | 322.3 |

| Female | 2.4* | 2.26–2.48 | 2,436 | 4,207,436 | 694.8 | 13.7 | 758.7 |

| χ21 | 1,266.6* | ||||||

| Age at Army Entry | |||||||

| < 21 | 0.7* | 0.68–0.76 | 6,471 | 19,095,671 | 406.6 | 62.2 | 330.3 |

| 21–24 | 1.0 | – | 2,139 | 7,531,739 | 340.8 | 24.5 | 460.8 |

| 25+ | 1.6* | 1.51–1.79 | 1,040 | 4,087,840 | 305.3 | 13.3 | 762.3 |

| χ22 | 392.9* | ||||||

| Current Age | |||||||

| < 21 | 5.6* | 5.06–6.23 | 3,315 | 4,624,915 | 860.1 | 15.1 | 927.1 |

| 21–24 | 2.9* | 2.61–3.17 | 3,499 | 9,230,699 | 454.9 | 30.1 | 478.3 |

| 25–29 | 1.6* | 1.50–1.80 | 1,756 | 7,119,756 | 296.0 | 23.2 | 275.6 |

| 30–34 | 1.0 | – | 635 | 4,239,435 | 179.7 | 13.8 | 165.7 |

| 35–39 | 0.7* | 0.58–0.76 | 300 | 3,344,500 | 107.6 | 10.9 | 111.7 |

| 40+ | 0.5* | 0.40–0.57 | 145 | 2,155,945 | 80.7 | 7.0 | 79.8 |

| χ25 | 1,832.5* | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 1.0 | – | 6,808 | 18,358,008 | 445.0 | 59.8 | 424.3 |

| Black | 0.7* | 0.63–0.71 | 1,415 | 6,972,415 | 243.5 | 22.7 | 281.3 |

| Hispanic | 0.7* | 0.69–0.79 | 979 | 3,557,179 | 330.3 | 11.6 | 313.9 |

| Asian | 0.7* | 0.60–0.76 | 286 | 1,217,486 | 281.9 | 4.0 | 286.3 |

| Other | 1.0 | 0.83–1.13 | 162 | 610,162 | 318.6 | 2.0 | 400.9 |

| χ24 | 245.4* | ||||||

| Education | |||||||

| < High School6 | 2.0* | 1.96–2.14 | 2,888 | 3,878,088 | 893.6 | 12.6 | 693.3 |

| High School | 1.0 | – | 6,380 | 23,503,980 | 325.7 | 76.5 | 324.8 |

| Some College | 0.7* | 0.62–0.83 | 191 | 1,704,591 | 134.5 | 5.5 | 237.1 |

| ≥ College | 0.6* | 0.52–0.70 | 191 | 1,628,591 | 140.7 | 5.3 | 194.9 |

| χ23 | 1,076.7* | ||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Never Married | 1.0 | 0.95–1.04 | 5,441 | 12,589,441 | 518.6 | 41.0 | 373.1 |

| Currently Married | 1.0 | – | 3,974 | 16,814,774 | 283.6 | 54.7 | 384.1 |

| Previously Married | 0.9 | 0.81–1.05 | 235 | 1,311,035 | 215.1 | 4.3 | 351.3 |

| χ22 | 1.6 | ||||||

| Total | – | – | 9,650 | 30,715,250 | 377.0 | 100 | – |

The sample of enlisted soldiers is a subset of the total sample (n = 193,617 person-months) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt. The analysis included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Total includes both cases (i.e., soldiers with a suicide attempt) and control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population (n=3.08 million).

Pop % = Population percent.

SR = Standardized rate.

< High School includes: General Educational Development credential (GED), home study diploma, occupational program certificate, correspondence school diploma, high school certificate of attendance, adult education diploma, and other non-traditional high school credentials.

Table 2.

Officers: Multivariate Associations of Socio-demographic Characteristics with Suicide Attempts in the Army STARRS 2004–2009 Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) Sample (n = 30,439).1

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)2 | Rate3 | Pop %4 | SR5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 1.0 | – | 89 | 5,127,689 | 20.8 | 84.6 | 21.3 |

| Female | 2.8* | 1.97–4.09 | 52 | 932,052 | 66.9 | 15.4 | 60.2 |

| χ21 | 31.5* | ||||||

| Age at Army Entry | |||||||

| < 21 | 1.1 | 0.71–1.81 | 26 | 1,221,426 | 25.5 | 20.2 | 26.6 |

| 21–24 | 1.0 | – | 73 | 3,615,273 | 24.2 | 59.7 | 23.0 |

| 25+ | 2.0* | 1.34–3.05 | 42 | 1,223,042 | 41.2 | 20.2 | 46.9 |

| χ22 | 11.3* | ||||||

| Current Age | |||||||

| ≤ 24 | 1.2 | 0.65–2.33 | 18 | 564,018 | 38.3 | 9.3 | 38.3 |

| 25–29 | 1.1 | 0.67–1.78 | 38 | 1,313,238 | 34.7 | 21.7 | 34.6 |

| 30–34 | 1.0 | – | 32 | 1,254,832 | 30.6 | 20.7 | 31.1 |

| 35–39 | 1.1 | 0.65–1.74 | 32 | 1,239,632 | 31.0 | 20.5 | 33.1 |

| 40+ | 0.5* | 0.26–0.79 | 21 | 1,688,021 | 14.9 | 27.9 | 14.1 |

| χ25 | 12.2* | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 1.0 | – | 93 | 4,451,893 | 25.1 | 73.5 | 26.5 |

| Black | 1.0 | 0.58–1.59 | 20 | 799,820 | 30.0 | 13.2 | 25.4 |

| Hispanic | 1.4 | 0.75–2.62 | 11 | 348,011 | 37.9 | 5.7 | 38.1 |

| Asian | 0.9 | 0.40–1.86 | 7 | 283,007 | 29.7 | 4.7 | 23.6 |

| Other | 2.2* | 1.10–4.20 | 10 | 177,010 | 67.8 | 2.9 | 59.8 |

| χ24 | 6.3 | ||||||

| Education | |||||||

| < High School6 | 3.1 | 0.74–12.49 | 4 | 98,604 | 48.7 | 1.6 | 43.5 |

| High School | 1.0 | – | 4 | 360,604 | 13.3 | 6.0 | 14.7 |

| Some College | 1.4 | 0.32–6.48 | 3 | 217,003 | 16.6 | 3.6 | 19.5 |

| ≥ College | 2.0 | 0.73–5.70 | 130 | 5,383,530 | 29.0 | 88.8 | 28.7 |

| χ23 | 2.8 | ||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Never Married | 1.3 | 0.86–1.91 | 53 | 1,500,853 | 42.4 | 24.8 | 32.3 |

| Currently Married | 1.0 | – | 81 | 4,306,281 | 22.6 | 71.1 | 25.5 |

| Previously Married | 1.2 | 0.53–2.51 | 7 | 252,607 | 33.3 | 4.2 | 30.2 |

| χ22 | 1.5 | ||||||

| Total | – | – | 141 | 6,059,741 | 27.9 | 100 | – |

The sample of officers (including warrant officers) is a subset of the total sample (n = 193,617 person-months) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt. The analysis included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Total includes both cases (i.e., soldiers with a suicide attempt) and control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population (n=3.08 million).

Pop % = Population percent.

SR = Standardized rate.

< High School includes: General Educational Development credential (GED), home study diploma, occupational program certificate, correspondence school diploma, high school certificate of attendance, adult education diploma, and other non-traditional high school credentials.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Among enlisted soldiers, a significantly higher odds of suicide attempt was associated with: female gender (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 2.26–2.48); entering Army service at age 25 or older (OR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.51–1.79); current age of 29 or younger (ORs = 1.6–5.6); and having less than a high school education (OR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.96–2.14). Lower odds of attempt was associated with entering the Army prior to age 21 (OR = 0.7; 95% CI: 0.68–0.76); current age of 35 or older (ORs = 0.5–0.7); completion of at least some college (ORs = 0.6–0.7); and Black, Hispanic, or Asian race/ethnicity (all ORs = 0.7) (Table 1). Increased odds of suicide attempt among officers was associated with female gender (OR = 2.8; 95% CI: 1.97–4.09) and entering Army service at age 25 or older (OR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.34–3.05). Officers with a current age of 40 or older had decreased odds of attempt (OR = 0.5; 95% CI: 0.26–0.79) (Table 2).

Although females were more likely to attempt suicide regardless of rank, examination of the standardized rates (Tables 1 and 2) reveals that enlisted females had nearly 13 times the risk of female officers (758.7/60.2). Similarly, entering the Army at age 25 or older was associated with increased odds of a suicide attempt for both enlisted soldiers and officers. The standardized rate for this segment of enlisted soldiers was over 16 times greater than that of officers (762.3/46.9). While having a current age of 40 or older was protective for both enlisted soldiers and officers, risk among enlisted personnel in this age group was still 5.6 times higher than comparable officers (79.8/14.1).

Length of service

Adjusting for socio-demographic variables, enlisted soldiers in their first four years of service had higher odds of suicide attempt than those with 5–10 years of service (ORs = 1.5–2.4), whereas those serving for more than ten years had lower odds (OR = 0.5; 95% CI: 0.39–0.52) (Table 3). Additional pairwise analyses revealed that rates of attempted suicide differed significantly for these service length categories (χ21 = 226.9–390.2 all p’s < 0.0001). Length of service was not associated with suicide attempts among officers (χ23 = 6.3, p = 0.10), though the ORs demonstrated a similar downward trend beyond the second year of service (Table 4). Enlisted soldiers in their first two years of service had the greatest risk and a standardized suicideattempt rate over 10 times that of officers serving for the same amount of time (585.6/55.5).

Table 3.

Enlisted Soldiers: Multivariate Associations of Length of Service, Deployment Status, and Time Since Most Recent Mental Health Diagnosis with Suicide Attempts in the Army STARRS 2004–2009 Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) Sample (n = 163,178).1,2

| I. Length of Service1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)3 | Rate4 | Pop %5 | SR6 | |

| 1–2 years | 2.4* | 2.19–2.57 | 5,416 | 8,560,616 | 759.2 | 27.9 | 585.6 |

| 3–4 years | 1.5* | 1.41–1.63 | 2,278 | 6,819,878 | 400.8 | 22.2 | 369.7 |

| 5–10 years | 1.0 | – | 1,542 | 8,322,742 | 222.3 | 27.1 | 245.1 |

| > 10 years | 0.5* | 0.39–0.52 | 414 | 7,012,014 | 70.8 | 22.8 | 106.3 |

| χ23 | 589.3* | ||||||

| II. Deployment Status1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)3 | Rate4 | Pop %5 | SR6 | |

| Never deployed | 2.8* | 2.59–2.99 | 5,894 | 12,421,294 | 569.4 | 40.4 | 443.9 |

| Currently deployed | 1.0 | – | 940 | 7,173,140 | 157.3 | 23.4 | 165.7 |

| Previously deployed | 2.6* | 2.42–2.81 | 2,816 | 11,120,816 | 303.9 | 36.2 | 423.8 |

| χ22 | 839.3* | ||||||

| III. Times Since Most Recent Mental Health Diagnosis1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)3 | Rate4 | Pop %5 | SR6 | |

| No Diagnosis | 1.0 | – | 3,876 | 23,156,276 | 200.9 | 75.4 | 191.0 |

| 1 Month | 18.2* | 17.39–19.12 | 3,516 | 1,150,916 | 3,665.9 | 3.7 | 3,490.7 |

| 2–3 Months | 5.8* | 5.40–6.28 | 833 | 856,033 | 1,167.7 | 2.8 | 1,127.7 |

| 4–12 Months | 2.9* | 2.65–3.07 | 887 | 1,989,887 | 534.9 | 6.5 | 552.6 |

| 13+ Months | 1.4* | 1.31–1.58 | 538 | 3,562,138 | 181.2 | 11.6 | 276.4 |

| χ24 | 15,255.6* | ||||||

In separately examining the effects of length of service, deployment status, and mental health diagnosis, we controlled for the basic socio-demographic variables reported in Tables 1 and 2 (gender, age at entry into the Army, current age, race, education, marital status). All analyses also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

The sample of enlisted soldiers is a subset of the total sample (n = 193,617 person-months) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Total includes both cases (i.e., soldiers with a suicide attempt) and control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population (n=3.08 million).

Pop % = Population percent.

SR = Standardized rate.

Table 4.

Officers: Multivariate Associations of Length of Service, Deployment Status, and Time Since Most Recent Mental Health Diagnosis with Suicide Attempts in the Army STARRS 2004–2009 Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) Sample (n = 30,439).1,2

| I. Length of Service1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)3 | Rate4 | Pop %5 | SR6 | |

| 1–2 years | 1.8 | 0.98–3.42 | 29 | 654,829 | 53.1 | 10.8 | 55.5 |

| 3–4 years | 1.4 | 0.77–2.34 | 24 | 680,824 | 42.3 | 11.2 | 40.9 |

| 5–10 years | 1.0 | – | 39 | 1,487,839 | 31.5 | 24.6 | 29.1 |

| > 10 years | 0.7 | 0.36–1.17 | 49 | 3,236,249 | 18.2 | 53.4 | 18.8 |

| χ23 | 6.3 | ||||||

| II. Deployment Status1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)3 | Rate4 | Pop %5 | SR6 | |

| Never deployed | 1.3 | 0.80–2.18 | 62 | 2,293,862 | 32.4 | 37.9 | 27.9 |

| Currently deployed | 1.0 | – | 22 | 1,169,622 | 22.6 | 19.3 | 23.3 |

| Previously deployed | 1.3 | 0.76–2.06 | 57 | 2,596,257 | 26.3 | 42.8 | 30.3 |

| χ22 | 1.2 | ||||||

| III. Time Since Most Recent Mental Health Diagnosis1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Cases (N) | Total (N)3 | Rate4 | Pop %5 | SR6 | |

| No Diagnosis | 1.0 | – | 42 | 5,107,442 | 9.9 | 84.3 | 9.6 |

| 1 Month | 90.2* | 59.51–136.74 | 65 | 105,265 | 741.0 | 1.7 | 836.2 |

| 2–3 Months | 14.8* | 7.29–29.84 | 10 | 93,610 | 128.2 | 1.5 | 143.9 |

| 4–12 Months | 10.1* | 5.60–18.27 | 16 | 216,216 | 88.8 | 3.6 | 100.7 |

| 13+ Months | 2.3* | 1.04–4.87 | 8 | 537,208 | 17.9 | 8.9 | 22.0 |

| χ24 | 484.4* | ||||||

In separately examining the effects of length of service, deployment status, and mental health diagnosis, we controlled for the basic socio-demographic variables reported in Tables 1 and 2 (gender, age at entry into the Army, current age, race, education, marital status). All analyses also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

The sample of officers (including warrant officers) is a subset of the total sample (n = 193,617 person-months) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Total includes both cases (i.e., soldiers with a suicide attempt) and control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population (n=3.08 million).

Pop % = Population percent.

SR = Standardized rate.

A discrete-time hazard model examining time to suicide attempt (Figure 1) demonstrated a greatly elevated risk among enlisted soldiers during their first year in the Army, with risk peaking in the second month of service (102.5/100,000 person-months). Risk decreased substantially during the second year of service, followed by a more gradual decline. Risk among officers remained relatively stable across time.

Figure 1. Risk of Suicide Attempt by Month Since Entering the Army Among Enlisted Soldiers and Officers in the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) Sample, 2004–2009 (n = 193,617).1.

1The sample of 193,617 person-months includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in the administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Deployment status

Among enlisted soldiers, both never deployed and previously deployed soldiers had higher odds of suicide attempt relative to those who were currently deployed (ORs = 2.6–2.8), controlling for socio-demographic variables (Table 3). The pairwise difference between never and previously deployed was also significant (χ21 = 6.3, p = 0.012). Deployment status was not associated with suicide attempt among officers (χ22 = 1.2, p = 0.54), though the ORs were in the same direction as enlisted soldiers (Table 4). Never deployed enlisted soldiers, the group at greatest risk based on deployment status, accounted for a similar proportion of their respective population as the never deployed officers (40.4% vs. 37.9%) but had a standardized suicide attempt rate nearly 16 times higher (443.9/27.9). Although a smaller proportion of enlisted soldiers had previously deployed compared to officers (36.2% vs. 42.8%), their standardized rate of suicide attempt was approximately 14 times higher (423.8/30.3).

Mental health diagnosis

Of enlisted soldiers who attempted suicide, 59.8% had a history of a mental health diagnosis. For officers 70.2% who attempted suicide had a history of mental health diagnosis. For both enlisted soldiers and officers the majority of those with a history of a mental health diagnosis had a diagnosis recorded in the month prior to their attempt (60.9% of enlisted, 65.7% of officers). Controlling for socio-demographics, enlisted soldiers with a mental health diagnosis in the previous month had the highest odds of suicide attempt compared to those without a diagnosis (OR = 18.2; 95% CI: 17.39–19.12), with odds decreasing as the time since most recent diagnosis increased from 2–3 months (OR = 5.8; 95% CI: 5.40–6.28) to 13 months or more OR = 1.4; 95% CI: 1.31–1.58) (Table 3). Additional pairwise comparisons between the standardized suicide attempt rates for these time intervals since a diagnosis were also significant (χ21 = 153.2–2,910.4, all p’s < 0.0001). Officers with a mental health diagnosis in the previous month also had the greatest likelihood of attempt (OR = 90.2; 95% CI: 59.51–136.74), and longer intervals resulted in increasingly smaller odds ratios, ranging from 14.8 (95% CI: 7.29–29.84) for 2–3 months to 2.3 (95% CI: 1.04–4.87) for 13 months or more (Table 4). Most pairwise analyses of these intervals were significant (χ21 = 12.0–96.0, p’s < 0.0001–0.0005), except for 2–3 months versus 4–12 months (χ21 = 0.9, p = 0.35). The elevated suicide attempt rate in the month following documentation of a mental health diagnoses was over four times higher for enlisted soldiers than officers (3,490.7/836.2).

DISCUSSION

Using the comprehensive data on U.S. Army suicide attempts integrated within the Army STARRS HADS database, this study identified segments of the active duty Regular Army population at greatest risk of suicide attempt, highlighting pathways for further inquiry and intervention. Our findings suggest that enlisted soldiers and officers require unique considerations in research and prevention. Beyond potentially important differences in socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., higher education among officers), training, and occupational responsibilities, these groups also have distinct risk distributions. Enlisted soldiers comprise the majority of the Army population and account for the majority suicide attempts. Many of the socio-demographic risk factors among enlisted soldiers are consistent with the broader suicide attempt literature,15 including female gender, younger current age, Non-Hispanic White race, and lower educational attainment.

For clinicians assessing individual risk, it is important to distinguish between whom they are likely to see in practice versus who is at highest risk in the population. Similarly, program planners seeking to have the greatest impact on population health must consider population attributable risk when developing interventions for at risk groups. For example, female enlisted soldiers are over twice as likely as males to attempt suicide but account for only 13.7% of the active duty Regular Army. The consistency of gender as a predictor of suicide attempt suggests it may be beneficial to separately examine risk in males and females.7 Identification of gender-specific risk profiles would assist in the development and targeting of interventions, particularly for female soldiers, who are at greater risk than males and may require prevention programs that differ from those designed for a male-dominated Army population. In contrast, race was only associated with suicide attempts among enlisted soldiers, with Non-Hispanic Whites at greater risk than Black, Hispanic, or Asian soldiers. Both enlisted soldiers and officers were at increased risk if they entered Army service at age 25 or older, suggesting the importance of early intervention, e.g., additional training, education, and/or mental health resources for new soldiers over the age of 25.

This study revealed associations between suicide attempts and length of Army service. Enlisted soldiers were at elevated risk during their first tour of duty. In particular, the initial months following entry into the Army suggests the need for enhanced surveillance and preventive interventions. Recent studies found that nearly 39% of new soldiers report a pre-enlistment history of common internalizing or externalizing mental health disorders,16 and pre-enlistment suicide ideation, plans, and attempts are reported by 14.1%, 2.3%, and 1.9%, respectively.17 The combination of high population prevalence and high suicide attempt rate found in the current study suggests that evidence-based prevention targeting early-career enlisted soldiers could have the greatest impact on suicide attempt rates.

Importantly, currently deployed enlisted soldiers were not more likely to attempt suicide. The elevated risk among previously deployed enlisted soldiers is consistent with numerous studies documenting adverse mental health outcomes following deployment.18–22 However, our findings suggest that the greatest risk of suicide attempt is among enlisted soldiers who have never deployed. Further analysis is needed to determine whether mental health screening prior to deployment may have contributed to decreased risk in those currently deployed (i.e. a healthy deployed soldier effect).23 To better understand the relationship between deployment and suicide attempts, future studies should examine variables such as time to future deployment among those never deployed but anticipating deployment, time since deployment among those currently deployed, and time since redeployment among those previously deployed.

Mental health diagnoses, which are among the most consistent risk factors for suicidal behaviors,3 increased dramatically in the U.S. military over the past decade of war.24 In the current study, suicide attempts among enlisted soldiers and officers were associated with a history of mental health diagnosis, particularly in the previous month. Approximately 60% of enlisted soldiers and 70% of officers received a mental health diagnosis prior to their suicide attempt, suggesting that many at-risk soldiers have already been identified by the Army health care system as needing mental health services, providing opportunities for further risk assessment and intervention. Future research should examine which mental health disorders carry the greatest risk among soldiers and the trajectories of diagnoses over time.

A limitation of the current study is that we focused only on documented suicide attempts that came to the attention of the Army health care system. Undocumented suicide attempts may have risk and protective factors that differ from those identified here. In addition, we focused on a circumscribed set of socio-demographic and military predictors. Other potential risk and protective factors may contribute to Army suicide attempts, such as additional military characteristics (e.g., military occupational specialty, number of previous deployments, history of promotion and demotion) and mental health indicators (e.g., number and types of psychiatric diagnoses, treatment history).3

Conclusion

Our investigation found that enlisted soldiers in their first tour of duty account for the majority of medically documented suicide attempts. Those with a recent mental health diagnosis and those never deployed or previously deployed are at increased risk. Targeted suicide prevention programs that distinguish between enlisted soldiers and officers and incorporate characteristics such as gender, length of service, deployment status, and mental health diagnosis, will likely have the greatest impact on population health within the U.S. Army.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH).

Group Information

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System); Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) collaborating scientists: Lisa J. Colpe, PhD, MPH and Michael Schoenbaum, PhD; Army liaisons/consultants: COL Steven Cersovsky, MD, MPH (USAPHC) and Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (USAPHC).

Other team members were

Pablo A. Aliaga, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); K. Nikki Benevides, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul D. Bliese, PhD (University of South Carolina); Susan Borja, PhD (NIMH); Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD (Stony Brook University School of Medicine); Gregory G. Brown, PhD (University of California San Diego); Christina L. Wryter, BA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Catherine L. Dempsey, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Stephen E. Gilman, ScD (Harvard School of Public Health); Marjan G. Holloway, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Karestan C. Koenen, PhD (Columbia University); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E. McCarroll, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Rema Raman, PhD (University of California San Diego); Holly J. Ramsawh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Anthony Joseph Rosellini, PhD (Harvard Medical School); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); LCDR Patcho Santiago, MD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Michaelle Scanlon, MBA (NIMH); Jordan W. Smoller, MD, ScD (Harvard Medical School); Amy Street, PhD (Boston University School of Medicine); Michael L. Thomas, PhD (University of California San Diego); Patti L. Vegella, MS, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Leming Wang, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Christina L. Wassel, PhD (University of Pittsburgh); Simon Wessely, FMedSci (King’s College London); Hongyan Wu, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); LTC Gary H. Wynn, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School); and Bailey G. Zhang, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences).

Footnotes

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: As a cooperative agreement, scientists employed by NIMH (Colpe and Schoenbaum) and Army liaisons/consultants (COL Steven Cersovsky, MD, MPH USAPHC and Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH USAPHC) collaborated to develop the study protocol and data collection instruments, supervise data collection, interpret results, and prepare reports. Although a draft of this manuscript was submitted to the Army and NIMH for review and comment prior to submission, this was with the understanding that comments would be no more than advisory.

Disclaimer: The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institute of Mental Health, the US Department of the Army, or the US Department of Defense.

Additional Contributors: John Mann, Maria Oquedo, Barbara Stanley, Kelly Posner, Kohn Kelp, Dept of Psychiatry Columbia U, College of Physicians and Surgeons, and NY State Psychiatric Institute contributed to the early stages of the US Army STARRS development

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Author Contributions: Dr. Ursano had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kessler, Colpe, Fullerton, Heeringa, Naifeh, Schoenbaum, Ursano

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Aliaga, Kessler, Cox, Kao, Fullerton, Heeringa, Naifeh, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Stein, Ursano

Statistical Analysis: Aliaga, Kao, Kessler, Heeringa, Sampson, Ursano

Drafting of the manuscript: Aliaga, Kessler, Fullerton, Naifeh, Ursano

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Aliaga, Kessler, Colpe, Cox, Fullerton, Heeringa, Kao, Naifeh, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Stein, Ursano

Obtained funding: Kessler, Ursano

Administrative, technical, or material support: Aliaga, Kessler, Colpe, Fullerton, Heeringa, Kao, Naifeh, Ursano

Study supervision: Kessler, Sampson, Stein, Ursano

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Kessler has been a consultant over the past three years for J & J Wellness & Prevention, Inc., Lake Nona Institute, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Sanofi- Aventis Groupe, Shire US Inc., and Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc. and has had research support for his epidemiological studies over this time period from EPI-Q, and Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, and Walgreens Co. Kessler owns 25% share in DataStat, Inc. Stein has been a consultant for Healthcare Management Technologies, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Tonix Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, et al. Non-fatal suicidal behaviors in U.S. Army administrative records, 2004–2009: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) 2013 doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1006512. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lineberry TW, O’Connor SS. Suicide in the US Army. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2012;87:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nock MK, Deming CA, Fullerton CS, et al. Suicide among Soldiers: A review of psychosocial risk and protective factors. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2013;76:97–125. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2013.76.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenbaum M, Kessler RC, Gilman SE, et al. Predictors of suicide and accident death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4417. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Hourani LL, et al. 2008 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel: A Component of the Defense Lifestyle Assessment Program (DLAP) Research Triangle Park, North Carolina: RTI International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, Niven A, Wheeler G, Mysliwiec V. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep. 2011;34:1189–1195. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snarr JD, Heyman RE, Smith AM. Recent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a large–scale survey of the U.S. Air Force: Prevalences and demographic risk factors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:544–552. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):514–522. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush NE, Reger MA, Luxton DD, et al. Suicides and suicide attempts in the U.S. military, 2008–2010. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2013 doi: 10.1111/sltb.12012. in press. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojcik BE, Akhtar FZ, Hassell H. Hospital admissions related to mental disorders in U.S. Army soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine. 2009;174:1010–1018. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-01-6108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2014;72(2):107–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, et al. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2013;22(4):267–275. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gahm GA, Reger MA, Kinn JT, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Bush NE. Addressing the surveillance goal in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: The Department of Defense Suicide Event Report. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 1):S24–S28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roalfe AK, Holder RL, Wilson S. Standardisation of rates using logistic regression: A comparison with the direct method. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8:275. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosellini AJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Depression and Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.22316. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among new soldiers in the US Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Depression and Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.22317. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, Babeu LA. Substance use and mental health trends among U.S. military active duty personnel: Key findings from the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Military Medicine. 2010;175:390–399. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen YC, Arkes J, Williams TV. Effects of Iraq/Afghanistan deployments on major depression and substance use disorder: Analysis of active duty personnel in the US Military. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 1):S80–S87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells TS, LeardMann CA, Fortuna SO, et al. A prospective study of depression following combat deployment in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:90–99. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson IG, Ryan MAK, Hooper TI, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(6):663–675. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadermann AM, Engel CC, Naifeh JA, et al. Prevalence of DSM-IV major depression among U.S. military personnel: Meta-analysis and simulation. Military Medicine. 2012;177:47–59. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Parker JR, Warner CM, Hoge CW. Effectiveness of mental health screening and coordination of in-theater care prior to deployment to Iraq: A cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:378–385. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10091303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Mental disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2011. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report. 2012;19(6):11–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.