Abstract

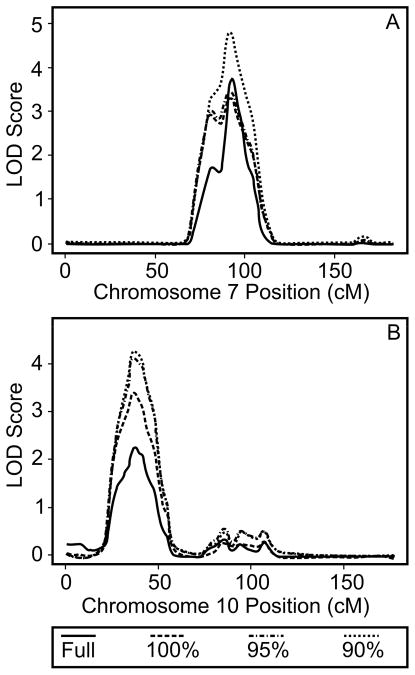

Cost-effective identification of novel pharmacogenetic variants remains a pressing need in the field. Using data from the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network, we identified genomic regions of relevance to fenofibrate response in a sample of 173 families. Our approach included a multipoint linkage scan, followed by selection of the families showing evidence of linkage. We identified a strong signal for changes in LDL-C on chromosome 7 (peak LOD score=4.76) in the full sample (n=821). The signal for LDL-C response remained even after adjusting for baseline LDL-C. Restricting analyses only to the families contributing to the linkage signal for LDL-C (N=19), we observed a peak LOD score of 5.17 for chromosome 7. Two genes under this peak (ABCB4 and CD36) were of biological interest. These results suggest that linked family analyses might be a useful approach to gene discovery in the presence of a complex (e.g. multigenic) phenotype.

Keywords: fenofibrate, lipids, family study

Background

Fenofibrate, an agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPAR-α), leads to blood lipid changes that are heritable and highly variable between individuals. However, known genetic factors only account for a modest proportion of inherited heterogeneity in treatment response (1), highlighting the need for cost-effective identification of novel, especially rare, pharmacogenetic variants. Previous simulations have shown that family-specific linkage analysis provides a powerful way to select samples that carry rare alleles, even when the aggregate evidence of linkage is weak (2).

To further our understanding of the genetic basis of lipid response to fenofibrate, we leveraged the family-based design of the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study. We performed a multipoint linkage scan to identify genomic regions of interest, followed by selecting individual families that show evidence of segregating together at those loci in order to inform identification of novel pharmacogenetic predictors (3).

Methods

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) GOLDN study was described in detail in previous publications (4, 5). Briefly, Caucasian families with at least 2 siblings were recruited from the Minneapolis and Salt Lake City centers of the NHLBI Family Heart study and asked to discontinue the use of lipid-lowering agents for at least 4 weeks prior to the first visit, to fast for at least 8 hours, and to abstain from alcohol for at least 24 hours prior to study visits. For this analysis, we used data from participants who received daily treatment with 160 mg of micronized fenofibrate for 3 weeks and had complete covariate information (n=821). Institutional Review Boards at all participating sites approved the study protocol..

We measured fasting blood lipids both before and after the fenofibrate intervention using previously described procedures (4–6). Lipid response was defined as a ratio of concentrations at visit 4 (post-3 week fenofibrate therapy) to visit 2 (baseline). To achieve a normal distribution of the residuals, we transformed the ratios of TG and TC (logarithmic transformation), HDL-C (square root transformation), and LDL-C (power transformation with exponent −0.2).

We began this analysis with 173 informational pedigrees with between 1 and 32 informational individuals, with a median of 3. 24 of the families contained only 1 informational individual The linkage analyses by MERLIN can be only performed on smaller families of size ≤20. We therefore trimmed large pedigrees using Mendel (7), reducing 21 families into 46 smaller informative pedigrees; two very large pedigrees were manually divided into 5 smaller pedigrees, yielding 198 pedigrees for analysis. Trimming increased the number of families with only a single informational individual from 24 to 50. After cutting the largest two pedigrees, the largest remaining pedigree had 16 informational individuals, and the median was still 3. The availability of dense single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) allowed us to pursue a natural experiment by doing linkage analyses in independent overlapping intervals of the genome. We chose a set of ten exclusive subsets of loci from the available GWAS genotype data for each chromosome for linkage analysis. Our dataset included 729,490 genotyped SNPs from Affymetrix 6.0 data after quality control, as described previously (5). We only considered loci with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of at least 0.25 to keep markers with high information content for the linkage analysis. From the list of eligible loci based on MAF, we chose the first available one by position. Based on positions from the genetic map of the loci in centi-Morgans (cM), we then included the next available locus that was at least 1 cM from the previous chosen locus, continuing this process until the end of the chromosome. Subsequently, we removed all of the loci chosen for the first set from the list of available loci, and repeated the process for each subsequent set to obtain ten complete sets of genome-wide SNPs in linkage equilibrium. Lastly, for this analysis, we used the deCode genetics map, which is based on the Kosambi mapping function.

The estimates of identity by descent (IBD) among related individuals vary both by true underlying IBD (as a function of position on the chromosome), and by properties of the markers used to estimate it, such as heterozygosity. We used MERLIN (8) to search for evidence of linkage on each chromosome using the 10 sets of loci identified by the criteria described above. We adjusted for age, sex, and center in each of the models used for this analysis. We also ran additional models adjusting for baseline values of HDL-C and LDL-C, in addition to age, sex, and center.

Family aggregate linkage analysis: We reran the MERLIN analyses for the genomic regions that attained a logarithm of odds (LOD) score of at least 2.0 for a majority of the ten marker subsets, specifying the option to calculate the contribution of each individual family to the total LOD score. At each marker for which the total LOD score was at least 1.8, we calculated the total of the strictly positive individual family contributions. We considered a significant family contribution to be at least 0.5% of the total score. For example, if the total LOD score for all families was 2, and the total LOD score for all families that had only a positive contribution was 5, then a family was considered a ‘significant contributor’ at that marker if the family’s individual LOD score was 0.5% of 5, i.e. 0.025. For all of the markers in all ten subsets, we calculated the proportion of times that families were classified as significant contributors, and for this report, we report results for the families that were significant contributors for at least 9 of the 10 subsets.

Results

A total of 407 of the 821 individuals in this sample were male. There were no statistically significant differences in age or study site by gender. The mean age for individuals in this sample was 46.0 years (SD=53.9) for men and 48.5 (SD=15.8) for women. Transformed mean values for HDL-C and LDL-C were 0.98 (SD=1.6) and 4.2 (SD=1.6), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in LDL-C by gender, but no difference in HDL-C by gender. In the full sample, we identified a strong signal for changes in LDL-C on chromosome 7 and one for changes in HDL-C on chromosome 10 with peak LOD scores equal to 4.76 and 2.57, respectively. After adjusting for baseline LDL-C and HDL-C in the linkage analysis for the full sample, the signal for LDL-C remained (peak LOD score=4.76), but the signal for HDL-C decreased (peak LOD score=2.08). We also performed linkage analyses for TC and TG, however those results were not significant (peak LOD scores were less than 2.0).

Table 1 summarizes the results of the family-aggregate linkage analysis. There were 19 families that were significant contributors to the LDL-C result on chromosome 7 in the region of interest in all subsets. Of the 19 families that were significant contributors, the trimming algorithm processed only 2. Trimming resulted in removal of unrelated singletons and the largest family was cut into three smaller pedigrees, two of which were among the 19 families. The third pedigree did not meet the significant criterion to be a ‘significant contributor’ to the evidence for linkage, but it’s contribution at each marker was positive, so it is consistent with contributing to the overall evidence for linkage in this region. Significant contributors did not differ from the full sample on key characteristics, e.g. mean lipid levels (P-values ranging from 0.19 to 0.26). The total LOD score limited to the 19 families ranged from 4.61 to 5.17. We did not perform the family-aggregate analysis for the HDL-C response given that the signal was attenuated after adjustment for baseline values of HDL-C in the full sample analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of overall and family-aggregate linkage analysis in the GOLDN study.

| Chromosome | Trait | Subset | Families | Start (cM)** | End (cM)** | Peak LOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | LDL-C | Full | 198 | 88.632 | 123.549 | 2.27 |

| 90% | 20 | 91.617 | 124.731 | 5.17 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 10 | HDL-C | Full | 198 | 28.747 | 44.702 | 2.57 |

| 90% | 35 | 23.516 | 51.095 | 4.75 | ||

90% of the subset is the set of families that were significant contributors to the linkage signal for at least 90% of the individual markers across all marker subsets.

Start and stop positions are the first and last position at which the LOD score is at least 2.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the utility of an aggregate-family based approach to linkage analysis, which can be useful in the identification of genomic regions in studies of multigenic, complex traits, including drug response. Many of the genetic predictors of treatment response are characterized by both small effect sizes and low minor allele frequency, hindering statistical power and raising research costs. Our findings show that in a pharmacogenetic study of lipid response to fenofibrate, aggregate informative family estimates yield strong evidence of linkage and can enrich linkage signals observed in the entire population. We also performed a secondary Loki/SOLAR (9–11) analysis to determine whether we could attain similar results if the large pedigrees were not cut. SOLAR does not have the capability of producing a per-family statistic, so this analysis is not useful for ascertaining which specific families contributed to the linkage signal. In our analysis, cutting the two large pedigrees had no noticeable effect on the results for the full sample. To our knowledge, our study is the first one to document the link between genomic regions on chromosomes 7 for LDL-C response to fenofibrate, respectively, in a large sample of metabolically healthy individuals.

We identified several genes, but only 2 genes were of biological interest under the linkage peak on chromosomes 7 (ABCB4, and CD36). Of particular biological salience are the putative associations with variants in ABCB4 and CD36 on chromosome 7. The role of ABCB family members - including ABCB4 - on the effects of drug-resistance and secretion of cholesterol, phospholipids, and other compounds into bile, have been previously explored (12). CD36 may also be involved in the transport and/or regulation of fatty acids, in addition to the binding of fatty acids including anionic phospholipids and oxidized LDL. Notably, our group has previously reported associations between CD36 and lipoprotein response to fenofibrate in a genome-wide association study (13).

On balance, our findings demonstrate the value of identifying families that segregate together at loci of potential interest rather than attempting to identify linkage associations from individual families in studies of complex traits. These results lay the groundwork for future sequencing studies in specific families contributing to linkage peaks on chromosomes 7 in fenofibrate response.

Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant U01HL072524-04.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Smith JA, Arnett DK, Kelly RJ, et al. The genetic architecture of fasting plasma triglyceride response to fenofibrate treatment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:603–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5202003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi G, Simino J, Rao DC. Enriching rare variants using family-specific linkage information. BMC Proc. 2011;5 (Suppl 9):S82. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S9-S82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden DW, An SS, Palmer ND, et al. Molecular basis of a linkage peak: exome sequencing and family-based analysis identify a rare genetic variant in the ADIPOQ gene in the IRAS Family Study. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4112–4120. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corella D, Arnett DK, Tsai MY, et al. The −256T>C polymorphism in the apolipoprotein A-II gene promoter is associated with body mass index and food intake in the genetics of lipid lowering drugs and diet network study. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1144–1152. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aslibekyan S, Kabagambe EK, Irvin MR, et al. A genome-wide association study of inflammatory biomarker changes in response to fenofibrate treatment in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drug and Diet Network. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:191–197. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834fdd41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabagambe EK, Ordovas JM, Hopkins PN, et al. The relation between erythrocyte trans fat and triglyceride, VLDL- and HDL-cholesterol concentrations depends on polyunsaturated fat. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange K, Papp JC, Sinsheimer JS, et al. Mendel: the Swiss army knife of genetic analysis programs. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1568–1570. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, et al. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath S. Markov chain Monte Carlo segretation and linkage analysis for oligogenic models. Am J Hum Gen. 1997:748–760. doi: 10.1086/515506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heath SCSG, Thompson EA, Tseng C, Wisman EM. MCMC segregation and linkage analysis. Genetic Epidemiology. 1997:1011–1015. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1997)14:6<1011::AID-GEPI75>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.J ALaB. Multipoint quantitative trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. 1998:62. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazier-Wood AC, Aslibekyan S, Borecki IB, et al. Genome-wide association study indicates variants associated with insulin signaling and inflammation mediate lipoprotein responses to fenofibrate. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:750–757. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328357f6af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]