Abstract

Objective

To examine the independent and joint relationships of poor subjective sleep quality, and antepartum depression with suicidal ideation among pregnant women.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 641 pregnant women attending prenatal care clinics in Lima, Peru. Antepartum depression and suicidal ideation were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scale. Antepartum subjective sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Logistic regression procedures were performed to estimate odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) adjusted for confounders.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of suicidal ideation in this cohort was 16.8% and poor subjective sleep quality was more common among women endorsing suicidal ideation as compared to their counterparts who did not (47.2%vs.24.8%, p<0.001). After adjustment for confounders including maternal depression, poor subjective sleep quality (defined using the recommended criteria of PSQI global score of >5vs. ≤5) was associated with a 1.7-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR=1.67; 95%CI 1.02–2.71). When assessed as a continuous variable, each 1-unit increase in the global PSQI score resulted in an 18% increase in odds for suicidal ideation, even after adjusting for depression (aOR=1.18; 95%CI 1.08–1.28). Women with both poor subjective sleep quality and depression had a 3.5-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR=3.48; 95%CI 1.96–6.18) as compared with those who had neither risk factor.

Conclusion

Poor subjective sleep quality was associated with increased odds of suicidal ideation. Replication of these findings may promote investments in studies designed to examine the efficacy of sleep-focused interventions to treat pregnant women with sleep disorders and suicidal ideation.

Keywords: Sleep Quality, Suicide Ideation, Suicide, Depression, Pregnancy

Introduction

Suicide is a preventable global public health problem with profound personal, societal and economic consequences [1–6]. Worldwide, suicide accounts for about one million deaths annually and 71% of all violent deaths in women (57% in men) [5, 6]. Globally, suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15 to 29 year olds [7–9]. Despite improvements in awareness and treatment, worldwide suicide rates have remained stable or have increased among some selected populations in the US and elsewhere.[2, 6, 10] It is estimated that 10 to 25 nonlethal suicide attempts occur for every completed suicide.[11] In the US, suicide attempts account for some 400,000 emergency room visits annually [3]. Commonly identified risk factors for suicidal behaviors include affective disorders, substance use disorder, prior suicide attempt, adverse childhood experiences, family history of psychiatric disorders including substance abuse, family history of suicide, family violence, exposure to suicidal behaviors of others, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders [12–14] and incarceration [6, 15, 16]. An emerging body of literature suggests that sleep complaints including objective and subjective sleep disturbances such as insomnia, nightmares and poor sleep quality are risk factors for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and completed suicide [1, 4, 17–21]. On the basis of this emerging literature, sleep complaints are now listed among the top 10 warning signs of suicide by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [22].

Remarkably, few studies have focused on identifying risk factors for suicidal ideation among pregnant women in spite of the following: (1) increasing recognition of the prevalence and consequences of antepartum depression [23, 24]; (2) recognition of associations of suicidal ideation with depression among non-pregnant women and men [4, 25]; (3) recognition that suicidal ideation is a risk factor for suicidal attempts and completed suicide [25]; and (4) that 5% to 14% of women endorse suicidal ideation during the perinatal period [26]. Of note, suicidal attempts in pregnancy are associated with adverse obstetric, fetal, and neonatal outcomes including early fetal loss, premature labor, cesarean delivery, and blood transfusion [27–29]. Putative risk factors and correlates of antepartum suicidal ideation reported by other investigative teams include smoking, teen pregnancy, unplanned pregnancy, poor family functioning, exposure to intimate partner violence and common mental disorders [25, 30, 31]. However, despite consistent documentation of associations of poor sleep quality and sleep disorders with suicidal ideation among men and non-pregnant women [1, 4, 19] none have assessed the extent to which, if at all, poor sleep quality and sleep disturbances are correlates of suicidal ideation among pregnant women. Pregnancy is a period characterized by many physiologic changes, including variations in energy and sleep demands, often leading to sleep disturbances[32].Poor sleep quality and other sleep disturbances in early pregnancy have been linked to adverse perinatal outcomes including gestational diabetes mellitus [33], preterm birth [34–37], fetal growth restriction [34], preeclampsia [37–39] and maternal depression [40]. Therefore, we sought to fill this important gap in the literature by examining the relationship of maternal self-reported suicidal ideation with subjective sleep quality during early pregnancy. Several neurobiological pathways implicated in sleep disturbances and depression have been linked with suicidal ideation [41]. These include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis alterations, elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines, and decreased serotonergic tone [41]. On the basis of available literature from non-pregnant women [4, 19] adolescents and children [42], we hypothesized that poor subjective sleep quality would be associated with increased odds of antepartum suicidal ideation. We also hypothesized that the odds for suicidal ideation in relation to poor subjective sleep quality would be particularly pronounced among women with co-morbid antepartum depression. An understanding of these relationships is of particular interest among low-income Peruvian women given the high burden of intimate partner violence and associated adverse mental and physical health outcomes in this population.[43, 44].

Methods

The PrOMIS Study

The population for the present cross-sectional study was drawn from participants of the ongoing Pregnancy Outcomes, Maternal and Infant Study (PrOMIS) Cohort, designed to examine maternal social and behavioral risk factors of preterm birth and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. The study population consists of women attending prenatal care clinics at the Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal (INMP) in Lima, Peru. The INMP is the primary reference establishment for maternal and perinatal care operated by the Ministry of Health of Peru. Recruitment began in February 2012. Trained research personnel approached women in prenatal clinic waiting areas using an approach and recruitment script to determine their interest and eligibility for participating in the study. Women eligible for inclusion were those who initiated prenatal care prior to 16 weeks gestation. Women were ineligible if they were younger than 18 years of age, did not speak and read Spanish, or had completed more than 16 weeks gestation.

Enrolled participants were invited to take part in an interview where trained research personnel used a structured questionnaire to elicit information regarding maternal socio-demographics, lifestyle characteristics, medical and reproductive histories, and early life experiences of abuse. All study personnel were trained on interviewing skills, contents of the questionnaire, and ethical conduct of human research (including issues of safety and confidentiality). All participants provided written informed consent. The institutional review boards of the INMP, Lima, Peru and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration, Boston, MA approved all procedures used in this study.

Analytical Population

The study population for this report is derived from information collected from those participants who enrolled in the PrOMIS Study between October 2013 and February 2014. Of the 724 participants approached, 662 participants completed the interview (91.4% response rate). With 21 participants excluded because of missing information on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), 641 participants remained in the present analysis.

Sleep Quality Assessment

The PSQI is a 19-item, self-rated questionnaire designed to measure sleep quality and disturbances over the past month in clinical populations .[45] The 19 items are grouped into seven components, including 1) duration of sleep; 2) sleep disturbances; 3) sleep latency; 4) day dysfunction due to sleepiness; 5) sleep efficiency; 6) overall sleep quality; and 7) need medication to sleep. Each component is weighted equally on a 0–3 scale. By summing up seven component scores, a global PSQI score ranged from 0 to 21; higher global scores indicate worse sleep quality. In distinguishing good and poor sleepers, a global PSQI score > 5 yields a sensitivity of 89.6% and a specificity of 86.5%.[45] The Spanish-language version of the PSQI instrument has been shown to have good construct validity among pregnant Peruvian women [46].

Depressive Symptoms

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item, depression-screening scale [47] [48]. This questionnaire assesses 9 depressive symptom experienced by participants in the 14 days prior to evaluation. The PHQ-9 has been demonstrated to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing depressive disorders and suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women [49, 50]. Each item is rated on the frequency of a depressive symptom in the past two weeks. The PHQ-9 score was calculated by adding the assigned score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 to the response categories of “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day,” respectively. Question number 9 asks about suicidal ideation and was not considered in the total score for depression, we utilized only the first 8 questions to calculate an overall depression score as the PHQ-8. We categorized participants as having PHQ-8 score ≥ 10 as probable depression, similar to the PHQ-9 cut off score.

Suicidal Ideation and Other Covariates

Suicidal ideation was assesed on the basis of particiants’ responses to item 9 of the PHQ-9; “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself” in the 14 days prior to evaluation. If the response was “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day,” suicidal ideation was coded as “yes.” Participants responding “not at all” were classified as “no” for suicidal ideation. Participants’ age was categorized as follows: 18–20, 20–29, 30–34, and ≥35 years. Other sociodemographic variables were categorized as follows: maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. others); educational attainment (≤6, 7–12, and >12 completed years of schooling); marital status (married or living with partner vs. others); employment status (employed vs. not employed); access to basic foods (hard, not very hard); parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous); planned current pregnancy (yes vs. no); self-reported health in the last year (good vs. poor), experience of any lifetime intimate partner violence (yes vs. no), exerince of any childhood physical or sexual abuse (yes vs. no), and gestational age at interview.

Statistical Analyses

Frequency distributions of maternal sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics were examined. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student’s t tests for continuous variables were used to assess differences in the distributions of covariates for women with and without suicidal ideation. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range.

We fitted logistic regression models to derive odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for suicidal ideation in relation to maternal subjective reports of poor subjective sleep quality and sleep patterns. To assess confounding, we entered covariates into each model one at a time and compared adjusted and unadjusted ORs. Final models included covariates that altered unadjusted ORs by at least 10% and those that were identified a priori as potential confounders. Given that depression has been implicated as an important confounder or effect modifier of sleep disturbance and suicidality associations, [1] we reported results from models with and without adjustments for depression. Further, to assess the joint and independent effect of poor subjective sleep quality and depression on risk of suicidal ideation, we categorized participants into four groups based on combinations of suicidal ideation and depression status. The four resulting categories were as follows: (1) no suicidal ideation and no depression, (2) suicidal ideation only, (3) depression only, and (4) suicidal ideation and depression combined. Women with no suicidal ideation and no depression comprised the reference group, against which women in the other three categories were compared. In multivariable analyses, we evaluated linear trend in risk of suicidal ideation by treating PSQI global score as a continuous variable. We assessed the odds of suicidal ideation across tertiles of global PSQI score where tertiles are defined on the basis of the distribution of the scores for the entire cohort. We evaluated the linear trends in odds of suicidal ideation by treating the three tertiles as a continuous variable after assigning a score (i.e., 1, 2, 3) for successively higher tertiles. We explored the possibility of a nonlinear relationship of PSQI global score with suicidal ideation by fitting a multivariable logistic regression model that implemented the generalized additive modeling (GAM) procedures with a cubic spline function [51]. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and “R” software version 3.1.2. All reported confidence intervals were calculated at the 95% level. All reported p-values are two-tailed and deemed statistically significant at α=0.05.

Results

Selected socio-demographic and reproductive characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1. A total of 641 participants between the ages of 18 and 48 years (mean age=28.8 years, standard deviation (SD) =6.5 years) participated in the study. Approximately 16.8% of the cohort endorsed suicidal ideation during the index pregnancy. Overall, the majority of participants were Mestizos (75%)--predominant ethnicity (mixed White European and Amerindian ancestry) in Peru, with at least 7 years of education (95%), married or living with a partner (79%), multiparous (54%), and with an average gestational age of 9.1 (SD= 3.6) weeks at interview. Approximately, half of participants were unemployed (51%), and reported their access to basic foods was hard (49%). Participants endorsing suicidal ideation were younger and had a lower level of education (< 6 years) compared with those who did not endorse suicidal ideation.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Reproductive Characteristics of the Study Population (N = 641)

| Characteristics | All participants (N=

641) |

PHQ-9 Suicidal Ideation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 533) |

Yes (N = 108) |

P valuec | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) a | 28.8 ± 6.5 | 28.7 ± 6.5 | 29.0 ± 6.9 | 0.72 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–20 | 19 | 3.0 | 11 | 2.1 | 8 | 7.4 | 0.02 |

| 20–29 | 341 | 53.2 | 290 | 54.4 | 51 | 47.2 | |

| 30–34 | 145 | 22.6 | 120 | 22.5 | 25 | 23.1 | |

| ≥35 | 136 | 21.2 | 112 | 21 | 24 | 22.2 | |

| Education (years) | |||||||

| ≤6 | 26 | 4.1 | 17 | 3.2 | 9 | 8.3 | 0.01 |

| 7–12 | 330 | 51.5 | 269 | 50.5 | 61 | 56.5 | |

| >12 | 284 | 44.3 | 246 | 46.2 | 38 | 35.2 | |

| Mestizo | 477 | 74.4 | 397 | 74.5 | 80 | 74.1 | 0.93 |

| Married/living with a partner | 511 | 79.7 | 431 | 80.9 | 80 | 74.1 | 0.13 |

| Employed | 317 | 49.5 | 268 | 50.3 | 49 | 45.4 | 0.35 |

| Access to basic foods | |||||||

| Hard | 313 | 48.8 | 247 | 46.3 | 66 | 61.1 | 0.005 |

| Not very hard | 328 | 51.2 | 286 | 53.7 | 42 | 38.9 | |

| Nulliparous | 296 | 46.2 | 251 | 47.1 | 45 | 41.7 | 0.27 |

| Planned pregnancy | 262 | 40.9 | 227 | 42.6 | 35 | 32.4 | 0.07 |

| Gestational age at interview a | 9.1 ± 3.6 | 9.1 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 3.8 | 0.27 | |||

| Self-reported health (last year) | |||||||

| Good | 434 | 67.7 | 371 | 69.6 | 63 | 58.3 | 0.10 |

| Poor | 198 | 30.9 | 159 | 29.8 | 39 | 36.1 | |

| Self-reported health status during pregnancy | |||||||

| Good | 191 | 29.8 | 177 | 33.2 | 14 | 13.0 | <0.0001 |

| Poor | 439 | 68.5 | 352 | 66.0 | 87 | 80.6 | |

| Overall sleep quality | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Good (PSQI global score ≤ 5) | 458 | 71.5 | 401 | 75.2 | 57 | 52.8 | |

| Poor (PSQI global score > 5) | 183 | 28.6 | 132 | 24.8 | 51 | 47.2 | |

| Depression b | 146 | 22.8 | 102 | 19.1 | 44 | 40.1 | <0.0001 |

| Any lifetime sexual or physical abuse by intimate partner | |||||||

| No | 425 | 66.3 | 378 | 70.9 | 47 | 43.5 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 213 | 33.2 | 154 | 28.9 | 59 | 54.6 | |

| Any childhood physical or sexual abuse | |||||||

| No | 162 | 25.3 | 152 | 28.5 | 10 | 9.3 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 472 | 73.6 | 376 | 70.5 | 96 | 88.9 | |

Due to missing data, percentages may not add up to 100%.

Abbreviations: PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9

: Mean ± SD (standard deviation)

: Depression was defined as the PHQ-8 score ≥ 10.

: For continuous variables, P-value calculated using Student’s t test; for categorical variables, P-value was calculated using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test.

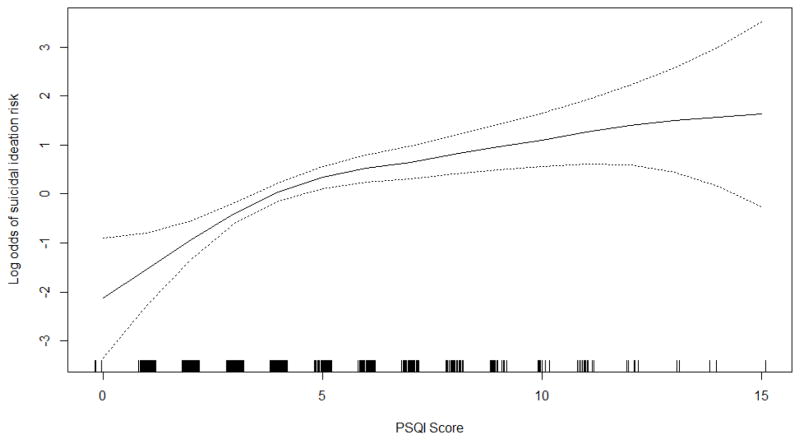

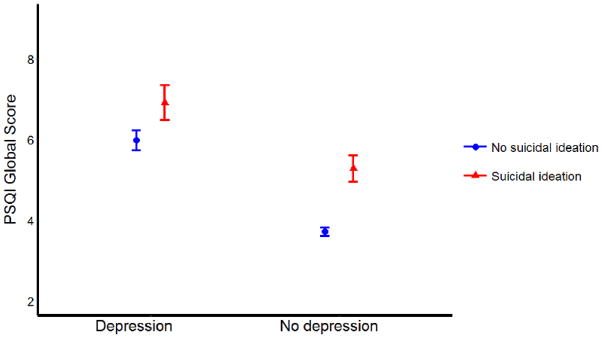

Mean PSQI global scores were higher among women with suicidal ideation as compared to those without suicidal ideation (mean ± SD: 5.9 ± 2.8 vs. 4.2 ± 2.5; p-value <0.0001), and this pattern of association was evident even when we stratified the cohort according to maternal antepartum depression status (Figure 1). Supplemental Table 1 shows the distribution of the PSQI sleep component subscales across suicidal ideation groups. Compared with those who did not endorse suicidal ideation participants endorsing suicidal ideation were more likely to report short sleep duration, long sleep latency, daytime dysfunction due to sleepiness, poor sleep efficiency and sleep medicine use.

Figure 1. Self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score, Sleep Quality a, Depression Status b, and Suicidal Ideation (N = 639 c).

Error bar stands for standard error

a: Good sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score ≤5; poor sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score >5.

b: No depression was defined as the Patient Health Questionnare-8 (PHQ-8) score < 10; depression was defined as the PHQ- 8 score ≥ 10.

c: Two participants were excluded due to missing information on the PHQ-8.

We examined odds of suicidal ideation according to the maternal subjective poor (global PSQI score > 5) and good sleep quality (global PSQI score ≤ 5) status (Table 2). Participants classified as poor sleepers had a 2.7-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR=2.72; 95% CI 1.78–4.16) as compared with those classified as good sleepers. After adjustment for maternal age, parity, access to basics, and exposure to intimate partner violence, the association was attenuated but remained statistically significant (aOR=2.19; 95% CI 1.40–3.42). In order to estimate the association of poor subjective sleep quality and suicidal ideation, independent of depression, we next included maternal depression status in the multivariable model. As shown in Table 2, even after adjustment for maternal depression, poor subjective sleep quality was found to be statistically significantly associated with an increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR=1.67; 95% CI 1.02–2.71). Poor sleepers had an almost 1.67-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation as compared with good sleepers.

Table 2.

Model Statistic for Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score Associated with Suicidal Ideation (N=641)

| PSQI global score | PHQ-9 Suicidal Ideation |

Unadjusteda OR (95% CI) | Adjusted b OR (95% CI) | Adjusted c OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 533) |

Yes (N = 108) |

||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Overall sleep quality | |||||||

| Good (PSQI global score ≤ 5) | 401 | 75.2 | 57 | 52.8 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Poor (PSQI global score > 5) | 132 | 24.8 | 51 | 47.2 | 2.72 (1.78–4.16) | 2.19 (1.40–3.42) | 1.67 (1.02–2.71) |

| PSQI global score | |||||||

| Lowest tertile (0–2) | 153 | 28.7 | 6 | 5.6 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle tertile (3–5) | 248 | 46.5 | 51 | 47.2 | 5.24 (2.20–12.51) | 4.96 (2.06–11.94) | 4.56 (1.89–11.01) |

| Highest tertile (≥ 6) | 132 | 24.8 | 51 | 47.2 | 9.85 (4.10–23.69) | 7.71 (3.16–18.83) | 5.76 (2.29–14.50) |

| P-value for trend | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||||

| PSQI global score (continuous)d | 4.2 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 2.8 | 1.26 (1.17–1.36) | 1.22 (1.13–1.32) | 1.18 (1.08–1.28) | ||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

: Unadjusted model

: Adjusted for age (years), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), access to basics (hard vs. not very hard), and lifetime intimate partner violence (any physical or sexual abuse vs. no abuse)

: Further adjusted for depression status (yes [PHQ-8 ≥ 10] vs. no [PHQ-8 < 10])

: Mean ± SD (standard deviation)

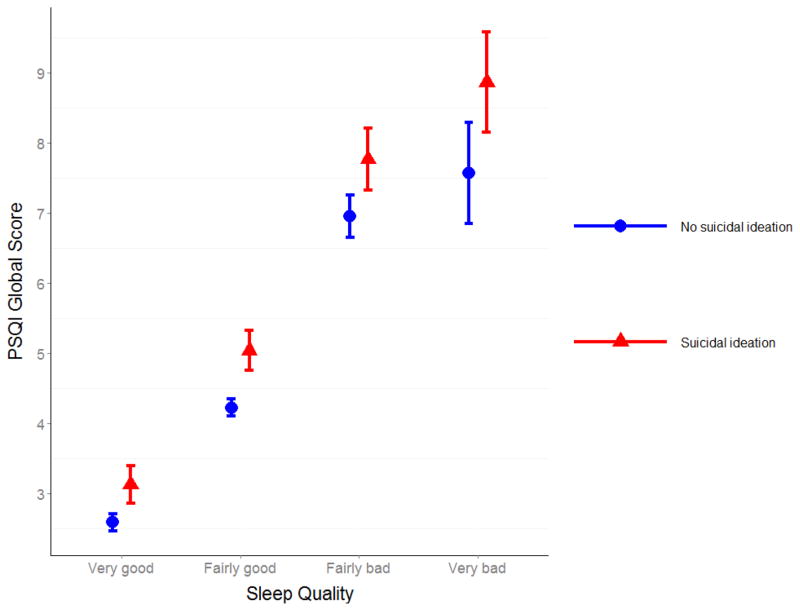

We next completed a series of analyses to explore the extent to which, if at all, global PSQI scores (reflecting lower sleep quality) increased the odds of suicidal ideation. For the initial set of exploratory analyses, we found that the odds of suicidal ideation increased across increasing tertiles of global PSQI score (p for trend <0.001) (Table 2 - middle panel). Compared with women who had the lowest PSQI global scores (PSQI global score ≤2), those with scores in the second tertile (PSQI global score=3–5) had a 4.6-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR=4.56; 95% CI 1.89–11.01). Of note, the association remained virtually unchanged when we included women’s history of childhood abuse in to the model (aOR=4.26; 95% CI 1.76–10.33). The odds of suicidal ideation was 5.8-fold higher for women with scores in the highest tertile (PSQI global score ≥6) (aOR=5.76; 95%CI 2.29–14.50) as compared with the lowest PSQI global scores; and this association remained even when history of childhood abuse was accounted for in multivariable models (aOR=5.13; 95%CI 2.02–13.02). When PSQI global score was modeled as a continuous variable (Table 2- bottom panel), we noted that the odds of suicidal ideation increased by 18% for every 1-unit increase in the PSQI global score (aOR=1.18; 95% CI 1.08–1.28) when all covariates including depression were controlled for. On the basis of these results, suggesting a linear component in odds of suicidal ideation with PSQI global score, we conducted additional analyses to explore the possibility of a nonlinear relation of global PSQI score with odds of suicidal ideation using regression procedures based on a generalized additive model. The results (Figure 2) confirmed increasing odds of suicidal ideation with increasing global PSQI score (reflecting worsening sleep quality). In addition, participants’ reports of self-rated perceived sleep quality was largely consistent with PSQI-derived global scores (Figure 3). Participants with suicidal ideation had the highest mean PSQI global scores compared with those without suicidal ideation.

Figure 2. Relation between Self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score and Risk of Suicidal Ideation (solid line) with 95% Confidence Interval (dotted lines)a.

aVertical bars along PSQI axis indicate distribution of study subjects.

Figure 3. Mean Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score by “ Perceived Sleep Quality” Component (N=641).

Error bar stands for standard error.

Given the well-known co-morbid association of poor sleep quality with depression, we conducted multivariate analyses to assess the independent and joint effect of each condition with the odds of suicidal ideation (Table 3). Women with depression only (classified as having good sleep quality) had a 2.83-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 2.83, 95% CI 1.43–5.61) as compared with women who had good sleep quality and no depression (the referent group). The aOR for women with poor subjective sleep quality only (no depression) was 2.01 (95% CI 1.10–3.67) when compared with the referent group, and this association was statistically significant. Women with both poor subjective sleep quality and depression had a 3.5-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR=3.48; 95% CI 1.96–6.18). The excess odds of suicidal ideation associated with poor subjective sleep quality and depression was greater than the sum of the excess odds for each risk factor considered independently, suggesting a greater-than-additive effect of poor subjective sleep quality and depression on the odds of suicidal ideation. However, the interaction term did not reach statistical significance (p=0.32).

Table 3.

Associations between Subjective Sleep Quality, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation (N = 639)

| Sleep quality a and depressive symptoms b | Suicidal ideation |

Unadjusted d OR (95% CI) | Adjusted e OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 531c) |

Yes (N = 108) |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Good sleep quality, no depression | 354 | 66.7 | 42 | 38.9 | Reference | Reference |

| Good sleep quality, depression | 46 | 8.7 | 15 | 13.9 | 2.75 (1.41–5.34) | 2.83 (1.43–5.61) |

| Poor sleep quality, no depression | 75 | 14.1 | 22 | 20.4 | 2.47 (1.39–4.38) | 2.01 (1.10–3.67) |

| Poor sleep quality, depression | 56 | 10.5 | 29 | 26.9 | 4.37 (2.52–7.57) | 3.48 (1.96–6.18) |

| P-value for interaction | 0.35 | 0.32 | ||||

: Good sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score ≤5; poor sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score >5.

: No depression was defined as the Patient Health Questionnare-8 (PHQ-8) score < 10; depression was defined as the PHQ - 8 score ≥ 10.

: Two participants were excluded due to missing information on the PHQ-8.

: Unadjusted model; odds ratio was calculated by including an interaction term between sleep quality and depression in the model.

: Adjusted for age (years), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), access to basics (hard vs. not very hard), and lifetime intimate partner violence (any physical or sexual abuse vs. no abuse); odds ratio was calculated by including an interaction term between sleep quality and depression in the model.

Discussion

The prevalence of suicidal ideation in this cohort of pregnant Peruvian women was 16.8%. We found that poor subjective sleep quality (when categorized using published cut-off score) was associated with a 67% increased odds of suicidal ideation, after adjusting for confounders and depression (aOR=1.67; 95% CI 1.02–2.71). When assessed as a continuous variable for every 1-unit increase in PSQI score the odds of suicidal ideation increased by 18% and this increase was independent of depression (aOR=1.18; 95% CI 1.08–1.28). The odds of suicidal ideation increased across successive tertiles of PSQI scores (1.00, 4.56 and 5.76 compared with the lowest tertile as the referent group). Lastly, women with both poor subjective sleep quality and depression had particularly high odds of suicidal ideation as compared with women who had neither risk factor (aOR=3.48; 95% CI 1.96–6.18).

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to explore the odds of suicidal ideation in relation to subjective sleep quality during pregnancy. Our findings, are however, generally consistent with existing literature documenting associations of subjective poor subjective sleep quality with odds of suicidal ideation [18, 52], suicidal behaviors [42], and completed suicide [1, 53, 54] among men and non-pregnant women. Further, our finding of a statistically significant association of suicidal ideation with depression is generally consistent with observations reported by Gavin et al. although the magnitude of association was considerably stronger in their study [30]. In their study of North American women receiving antepartum care in university-affiliated clinic, the authors reported that antepartum depression (assessed using the PHQ-9 short form) was associated with a 11.9-fold (OR=11.87; 95% CI 5.78–24.37) increased odds of suicidal ideation.

Associations between poor subjective sleep quality and increased odds of suicidal ideation are biologically plausible. First, sleep deprivation may lead to alterations in cognitive and emotional processing, which may contribute to an increased risk of impulsive and aggressive behaviors. Both emotion regulation and neurocognitive deficits are associated with elevated risk for suicidal behaviors, across age groups and outcome measures [55–59]. Results from both experimental and non-experimental manipulations of sleep studies support this thesis [60, 61]. Second, investigators have noted that sleep disturbances affect a number of neuroendocrine and metabolic pathways (e.g., cortisol, leptin, and ghrelin), and they have argued that perturbations in these pathways impact suicide risk [62]. Third, some investigators have argued that sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior share a common neurobiological processes. For example, given that serotonin, involved in promoting and modulating behavioral states, appears to play a significant role in suicide and in the regulation of sleep, investigators have argued that serotonergic dysfunction, particularly a reduction in the synthesis of serotonin, is believed to promote wakefulness [63, 64]. This thesis is supported by both animal and human studies. In rats Roman [65] demonstrated that sleep restriction (4 hours for 8 days) resulted in a desensitized 5-HT 1 A receptor system, and this effect persisted despite unlimited time for sleep recovery. In humans, low cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleactic acid (5-HIAA) have been consistently observed in patients with a history of suicide [66], and psychiatric patients who possesses the short allele of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism show an increased risk for suicide [67]. Finally, sleep disturbances, in addition to being a symptom of psychiatric disorders, may also be a risk factor for the development of mental illness which in turn may be strongly associated with suicide risk and as such a bi-directional relationship between sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders have been suggested [68–70].

The strengths of our study include a large sample size, the use of well-trained interviewers, and rigorous analytic approaches that included accounting for confounding control. However, limitations to our study must also be considered when interpreting our results. First, the cross-sectional design of the present study does not allow for an empirical assessment of the temporal relationship of alterations in subjective sleep quality and occurrence or onset of antepartum suicidal ideation. Longitudinal studies with more detailed assessment of lifetime and recurrent episodes of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors with concomitant assessments of chronic and acute depressive episodes, will enhance causal inferences in this area of research. Second, although the PSQI has been validated and has documented to be useful index for subjective sleep quality in diverse populations [45, 46, 71, 72], the possibility of misclassification of poor subjective sleep quality and other sleep parameters remains. Third, information concerning other important covariates such as frequent nightmares, and clinically relevant insomnia, which may influence sleep quality and suicidal ideation, were not measured Future studies should include assessment of these relevant covariates and should include assessment of suicidal behaviors. Fourth, given pregnancy-related physiological changes [32] it was not possible to delineate the sources of poor subjective sleep quality although our study was conducted in early pregnancy (average gestational age of 9.1 weeks). Future studies are warranted to understand the trajectories and specific causes of poor sleep quality during the course of pregnancy. Finally, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to South American, low-income pregnant women who registered for prenatal care early in pregnancy. Hence, care must be taken when generalizing the results to other obstetric populations. However, this concern about limited generalizability of our findings is mitigated, in part, by the observed consistency with reports of associations of subjective poor subjective sleep quality and suicidal ideation in other European [54], North American [1], and Asian [73] populations.

To our knowledge this is the first study to assess the independent relationship between subjective sleep quality and suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women. Understanding the independent association of subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation may alert health care providers that pregnant women reporting poor subjective sleep quality should be evaluated for suicidal ideation and management of sleep problems may reduce suicidal behavior among pregnant women. Improvements in the identification of risk factors for antepartum suicidal ideation may ultimately enhance the ability to identify, intervene and prevent death by suicide among pregnant and postpartum women. For instance, investigators have noted behavioral (e.g., sleep hygiene, stimulus control and imagery rehearsal therapy) and pharmacological interventions may be particularly promising modalities for reducing the risk of suicidal ideation [74]. Confirmation of our findings in other populations and further exploration of underlying biological mechanisms of observed associations are warranted. Future studies designed to examine ways of improving sleep should be carried out and findings should be used to guide the development and implementation of programs to identify, intervene and prevent death by suicide among pregnant and postpartum women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an award from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD-059835, T37-MD000149 and K01MH100428). The NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors wish to thank the dedicated staff members of Asociacion Civil Proyectos en Salud (PROESA), Peru and Instituto Especializado Materno Perinatal, Peru for their expert technical assistance with this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bernert RA, Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Joiner TE., Jr Association of poor subjective sleep quality with risk for death by suicide during a 10-year period: a longitudinal, population-based study of late life. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1129–1137. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Suicide among adults aged 35–64 years--United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(17):321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doshi A, Boudreaux ED, Wang N, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA., Jr National study of US emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1997–2001. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krakow B, Artar A, Warner TD, Melendrez D, Johnston L, Hollifield M, Germain A, Koss M. Sleep disorder, depression, and suicidality in female sexual assault survivors. Crisis. 2000;21(4):163–170. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.21.4.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Figures and facts about suicide. Geneva, Switzerland: Dept of mental health; [Accessed on 01/21/2015]. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_MNH_MBD_99.1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. [Accessed on 01/21/2015];Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/1/9789241564779_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 7.Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, Herndon J. Homicide: a leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):471–477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cliffe S, Black D, Bryant J, Sullivan E. Maternal deaths in New South Wales, Australia: A data linkage project. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48(3):255–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: Findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1056–1063. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding recent changes in suicide rates among the middle-aged: Period or cohort effects? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):680–688. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maris RW. Suicide. Lancet. 2002;360(9329):319–326. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nepon J, Belik SL, Bolton J, Sareen J. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(9):791–798. doi: 10.1002/da.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, Stein MB. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: A systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 Suppl):81–90. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moscicki EK. Identification of suicide risk factors using epidemiologic studies. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20(3):499–517. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agargun MY, Kara H, Solmaz M. Sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior in patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(6):249–251. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agargun MY, Kara H, Solmaz M. Subjective sleep quality and suicidality in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(3):377–381. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(96)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernert RA, Joiner TE. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: A review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(6):735–743. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernert RA, Joiner TE, Jr, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep. 2005;28(9):1135–1141. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(9):1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAMHSA: Sustance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Accessed on 01/21/2015];Suicide Prevention. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/suicide-prevention.

- 23.Mellor R, Chua SC, Boyce P. Antenatal depression: an artefact of sleep disturbance? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(4):291–302. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witt WP, Wisk LE, Cheng ER, Hampton JM, Creswell PD, Hagen EW, Spear HA, Maddox T, Deleire T. Poor prepregnancy and antepartum mental health predicts postpartum mental health problems among US women: A nationally representative population-based study. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4):304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Borges G, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czeizel AE, Tomcsik M, Tímár L. Teratologic evaluation of 178 infants born to mothers who attempted suicide by drugs during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1997;90 (2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czeizel AE. Attempted suicide and pregnancy. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3(1):45–54. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi SG, Gilbert WM, McElvy SS, El Kady D, Danielson B, Xing G, Smith LH. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after attempted suicide. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;107(5):984–990. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000216000.50202.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(3):239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang H, Faisal-Cury A, Chan YF, Tabb K, Katon W, Menezes PR. Suicidal ideation during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors among low-income women in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(2):135–138. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang JJ, Pien GW, Duntley SP, Macones GA. Sleep deprivation during pregnancy and maternal and fetal outcomes: Is there a relationship? Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu C, Enquobahrie D, Frederick IO, Abetew D, Williams MA. Glucose intolerance and gestational diabetes risk in relation to sleep duration and snoring during pregnancy: A pilot study. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Micheli K, Komninos I, Bagkeris E, Roumeliotaki T, Koutis A, Kogevinas M, Chatzi L. Sleep patterns in late pregnancy and risk of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction. Epidemiology. 2011;22(5):738–744. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31822546fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okun ML, Schetter CD, Glynn LM. Poor sleep quality is associated with preterm birth. Sleep. 2011;34(11):1493. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strange L, Parker K, Moore M, Strickland O, Bliwise D. Disturbed sleep and preterm birth: A potential relationship? Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;36 (3):166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y-H, Kang J-H, Lin C-C, Wang I-T, Keller JJ, Lin H-C. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. American journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;206(2):136. e131–136. e135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lefcourt LA, Rodis JF. Obstructive sleep apnea in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51 (8):503–506. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199608000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekholm EM, Polo O, Rauhala ER, Ekblad UU. Sleep quality in preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;167(5):1262–1266. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomfohr LM, Buliga E, Letourneau NL, Campbell TS, Giesbrecht GF. Trajectories of sleep quality and associations with mood during the perinatal period. Sleep. 2015 doi: 10.5665/sleep.4900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(9):e1160–1167. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee YJ, Cho SJ, Cho IH, Kim SJ. Insufficient sleep and suicidality in adolescents. Sleep. 2012;35(4):455–460. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrios YV, Sanchez SE, Nicolaidis C, Garcia PJ, Gelaye B, Zhong Q, Williams MA. Childhood abuse and early menarche among peruvian women. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56 (2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez-Beloz A, Williams MA, Sanchez SE, Lam N. Intimate partner violence and risk for depression among postpartum women in Lima, Peru. Violence Vict. 2009;24(3):380–398. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) in a cohort of Peruvian pregnant women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015 doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4936. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Group PHQPCS: Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Sanchez SE, Simon GE, Henderson DC, Barrios YV, Sanchez PM, Williams MA. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assess suicidal ideation among pregnant women in Lima, Peru. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0481-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhong Q, Gelaye B, Fann JR, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Cross-cultural validity of the Spanish version of PHQ-9 among pregnant Peruvian women: A Rasch item response theory analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized Additive Models. London: Chapman-Hall; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Jones MP, Phillips C, Simonsick E, Pearson JL, Wallace R. Risk factors for late-life suicide: A prospective, community-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):398–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Tokui N, Yoshimura T. Prospective cohort study of stress, life satisfaction, self-rated health, insomnia, and suicide death in Japan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(2):227–237. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.2.227.62876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bjorngaard JH, Bjerkeset O, Romundstad P, Gunnell D. Sleeping problems and suicide in 75,000 Norwegian adults: A 20 year follow-up of the HUNT I study. Sleep. 2011;34 (9):1155–1159. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, Clark L, Mazumdar S, Szanto K. Cognitive performance in suicidal depressed elderly: Preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(2):109–115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180f6338d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dour HJ, Cha CB, Nock MK. Evidence for an emotion-cognition interaction in the statistical prediction of suicide attempts. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(4):294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Russell M, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Harkavy-Friedman J, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior: attention control, memory and executive dysfunction in suicide attempt. Psychol Med. 2013;43(3):539–551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kohler CG, Turner TH, Gur RE, Gur RC. Recognition of facial emotions in neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(4):267–274. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900009202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker MP. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Helm E, Yao J, Dutt S, Rao V, Saletin JM, Walker MP. REM sleep depotentiates amygdala activity to previous emotional experiences. Curr Biol. 2011;21(23):2029–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zohar D, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, Lavie P. The effects of sleep loss on medical residents’ emotional reactions to work events: A cognitive-energy model. Sleep. 2005;28 (1):47–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferrie JE, Kumari M, Salo P, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M. Sleep epidemiology--a rapidly growing field. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(6):1431–1437. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ursin R. Serotonin and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(1):55–69. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adrien J. Neurobiological bases for the relation between sleep and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(5):341–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roman V, Van der Borght K, Leemburg SA, Van der Zee EA, Meerlo P. Sleep restriction by forced activity reduces hippocampal cell proliferation. Brain Res. 2005;1065(1–2):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asberg M. Neurotransmitters and suicidal behavior. The evidence from cerebrospinal fluid studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;836:158–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin PY, Tsai G. Association between serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism and suicide: results of a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55 (10):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA, Strawbridge WJ. Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: A prospective perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):81–88. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Staner L. Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Szklo-Coxe M, Young T, Peppard PE, Finn LA, Benca RM. Prospective associations of insomnia markers and symptoms with depression. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):709–720. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beaudreau SA, Spira AP, Stewart A, Kezirian EJ, Lui LY, Ensrud K, Redline S, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL Study of Osteoporotic F. Validation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in older black and white women. Sleep Med. 2012;13 (1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gelaye B, Lohsoonthorn V, Lertmeharit S, Pensuksan WC, Sanchez SE, Lemma S, Berhane Y, Zhu X, Velez JC, Barbosa C, et al. Construct validity and factor structure of the pittsburgh sleep quality index and epworth sleepiness scale in a multi-national study of African, South East Asian and South American college students. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e116383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gunnell D, Chang SS, Tsai MK, Tsao CK, Wen CP. Sleep and suicide: an analysis of a cohort of 394,000 Taiwanese adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48 (9):1457–1465. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0675-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krakow B, Ribeiro JD, Ulibarri VA, Krakow J, Joiner TE., Jr Sleep disturbances and suicidal ideation in sleep medical center patients. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1–3):422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.