Abstract

Background

Genetic variation in a region of chromosome 4p12 that includes the GABAA-subunit gene GABRA2 has been reproducibly associated with alcohol dependence (AD). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the association are unknown. This study examined correlates of in vitro gene expression of the AD-associated GABRA2 rs279858*C-allele in human neural cells using an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model system.

Methods

We examined mRNA expression of chromosome 4p12 GABAA subunit genes (GABRG1, GABRA2, GABRA4, and GABRB1 in 36 human neural cell lines differentiated from iPSCs using quantitative PCR and Next Generation RNA Sequencing. mRNA expression in adult human brain was examined using the BrainCloud and Braineac datasets.

Results

We found significantly lower levels of GABRA2 mRNA in neural cell cultures derived from rs279858*C-allele carriers. Levels of GABRA2 RNA were correlated with those of the other three chromosome 4p12 GABAA genes, but not other neural genes. Cluster analysis based on the relative RNA levels of the four chromosome 4p12 GABAA genes identified two distinct clusters of cell lines, a low-expression cluster associated with rs279858*C-allele carriers and a high-expression cluster enriched for the rs279858*T/T genotype. In contrast, there was no association of genotype with chromosome 4p12 GABAA gene expression in post-mortem adult cortex in either the BrainCloud or Braineac datasets.

Conclusions

AD-associated variation in GABRA2 is associated with differential expression of the entire cluster of GABAA subunit genes on chromosome 4p12 in human iPSC-derived neural cell cultures. The absence of a parallel effect in post-mortem human adult brain samples suggests that AD-associated genotype effects on GABAA expression, although not present in mature cortex, could have effects on regulation of the chromosome 4p12 GABAA cluster during neural development.

Keywords: Alcohol Dependence, GABAA Receptor, GABRA2, Gene Expression, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Introduction

GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the human brain (Olsen and Sieghart, 2009). The fast inhibitory effect of GABA in the mature nervous system is mediated through GABA type-A (GABAA) receptors, which are heteropentameric ligand-gated ion channels permeable to chloride (Hevers and Luddens, 1998). GABAA receptors are distributed throughout the brain and composed of a diverse set of 19 subunits (α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, θ, π, and ρ1–3) that vary in expression across brain regions (for a review, see (Olsen and Sieghart, 2009). The various GABAA receptor subtypes differ in subunit stoichiometry, a major determinant of their diverse pharmacological and electrophysiological properties (Barnard et al., 1998, Olsen and Sieghart, 2009). The majority of GABAA receptors contain two α, two β, and 1 γ subunit, with the α1β2γ2 and α2β3γ2 combinations comprising 75–85% of GABAA receptors in adult cortex (Rudolph et al., 2001).

In the human genome, the majority of GABAA subunit genes are clustered on four chromosomes: 4p12 (β1, α4, α2, γ1), 5q34 (β2, α6, α1, γ2), 15q11 (β3, α5, γ3) and Xq28 (θ, α3, ε) (Steiger and Russek, 2004). Homologous clusters of genes are found on mouse chromosomes 5, 11, 7 and × and are thought to have derived from a single ancestral αβγ cluster by gene duplication (Russek, 1999). Positioning of GABAA genes in tandem is believed to facilitate coordinated and tissue-specific co-regulation of gene expression by allowing clustered genes to share regulatory elements (Steiger and Russek, 2004, Barnard et al., 1998). Co-regulation of genes encoding the GABAA receptor subunits is evidenced by variation in RNA levels in post-mortem human brain samples over a range of developmental ages. At earlier stages of development, chr4p12 GABAA genes are expressed at higher levels than chromosome 5q34 genes. However, during development, chr4p12 genes are down regulated while chromosome 5q34 genes are up regulated (Fillman et al., 2010). Similarly, in rhesus monkeys, there is a developmental up regulation of the α1 subunit and a down regulation of the α2 subunit in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which coincide with decreases in the decay time of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (Hashimoto et al., 2009).

Alcohol use disorders are prevalent, affecting more than 8% of the U.S. population (Grant et al., 2004). They have multiple and complex etiologies including a strong genetic component, with heritability estimates ranging from 50–60% (Gelernter and Kranzler, 2009). Among the most widely studied genetic associations with alcohol dependence (AD) are those involving single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contained in a ~140 kb haplotype block spanning the 3’-region of GABRA2 and the adjacent intergenic GABRA2-GABRG1 region on chr4p12 (Covault et al., 2008, Edenberg et al., 2004, Covault et al., 2004). The association of SNPs in this region with AD has been replicated in multiple studies and across different populations (Ittiwut et al., 2012, Enoch et al., 2009, Lappalainen et al., 2005, Bauer et al., 2007, Fehr et al., 2006, Soyka et al., 2008, Li et al., 2014), but lack of replication has also been reported (Matthews et al., 2007, Lydall et al., 2011). SNPs in this haplotype block have also been associated with drug dependence (Agrawal et al., 2006), suggesting that variability in replication may relate in part to differing co-morbidities among samples. The most commonly examined tag-SNP in this region, rs279858, a synonymous SNP in exon 5 of GABRA2, was the only candidate marker associated with AD in a genome-wide analysis of candidate genes (Olfson and Bierut, 2012). The molecular mechanism by which GABRA2 polymorphisms influence risk for AD is unknown. The absence of a linked coding variant suggests that AD-associated variation in this region is in linkage disequilibrium with an as-yet-unidentified functional variant that influences the developmentally regulated expression of GABRA2 or adjacent chr4p12 GABAA subunit genes. This could result in subtle differences in neural connectivity and subsequent behavioral effects. Support for this hypothesis comes from reports that SNPs in GABRA2 are associated with intermediate neural phenotypes, including fast beta frequency electroencephalographic (EEG) activity (Edenberg et al., 2004, Lydall et al., 2011), increased activation of the insular cortex during reward anticipation (Villafuerte et al., 2012), differences in activation of the medial frontal cortex and ventral tegmental area by alcohol cues (Kareken et al., 2010) and increased activation of the nucleus accumbens in reward anticipation paradigms (Heitzeg et al., 2014).

To explore molecular effects of AD-associated variants in the GABRA2 haplotype block, we used an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model system (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006, Takahashi et al., 2007). Generation of iPSCs from individuals with known genotypes and subsequent differentiation into neural cells provides an opportunity to explore molecular phenotypes of AD-associated genetic variants in vitro. We examined neural cell cultures differentiated from 36 iPSC lines from 21 donor subjects with different GABRA2 rs279858 genotypes and RNA expression of genes encoding GABAA receptor subunits was examined. Our results indicate that chr4p12 AD risk alleles are associated with differences in RNA expression of all four GABAA genes located in this region in this in vitro model system.

Materials and Methods

iPSC Generation

Fibroblast cell lines were generated from skin punch biopsies donated by participants enrolled in a study of the effects of alcohol in social drinkers (9 males) (Milivojevic et al., 2014) or in a clinical trial for heavy drinkers (10 males and 2 females) (Kranzler et al., 2014) at the University of Connecticut Health Center (UCHC). All fibroblast samples were from Caucasian donors. Fibroblasts were reprogrammed to pluripotency by the UCHC Stem Cell Core using retrovirus constructs expressing five factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, and LIN28) for 34 lines or sendai virus constructs expressing four factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) for 2 lines. 2 to 4 weeks after viral transduction, individual iPSC colonies were identified by morphological characteristics and selected clones were expanded and cultured as separate cell lines in human embryonic stem cell media on a feeder layer of irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

Neural Differentiation

Neural cells generated from 36 iPSC lines were examined, including two independent lines from each of 15 donors and one line each from an additional 6 donors. iPSCs were differentiated into forebrain lineage neural cultures using an embryoid body-based protocol developed by the WiCell Institute (#SOP-CH-207 Rev A, www.wicell.org, Madison, WI). For details on the neural differentiation methods used see (Lieberman et al., 2012). Mature cultures (12 weeks post-neural plating) generated using this protocol contain a mixture of glial cells and neurons with spontaneous electrical activity, functional ionotropic GABAA and glutamate receptors, and the ability to generate action potentials (Lieberman et al., 2012). A comparison of transcriptome profiles for human iPSC-derived forebrain lineage neural cultures and human post-mortem brain tissue suggests that 6–12 week iPSC neural cultures have a gene expression profile most similar to first trimester forebrain tissue (Brennand et al., 2014, Mariani et al., 2012).

Reverse Transcription- Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Neural cultures 12–17 weeks post-plating were mechanically harvested and RNA extracted using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and cDNA was synthesized using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies) using 2 µg of total RNA. Relative transcript levels represented in the resulting cDNA were measured by real-time qPCR using an Applied Biosystems 7500 instrument and FAM-labeled TaqMAN Assays (Life Technologies) for: GABRA1 (Hs00971228_m1), GABRA2 (Hs00168069_m1), GABRA4 (Hs00608034_m1), GABRB1 (Hs00181306_m1), GABRG1 (Hs00381554_m1), GABRG2 (Hs00381554_m1), GABRD (Hs00181309_m1), RBFOX3 (Hs01370653_m1), GAD2 (Hs00609534_m1), and SLC17A7 (Hs00220404_m1). VIC-labeled GUSB (β–glucuronidase, 4326320E) was used as a within-well reference gene for normalization. Each sample was assayed in triplicate and a standard curve using cDNA generated from mature iPSC-derived neural cells from one subject was included on each qPCR assay plate to allow pooling of relative RNA expression levels among all samples. CT values for target genes and the internal reference gene were converted to relative expression levels using the standard curve method, which compares each experimental sample with a calibrator reference RNA sample whose RNA level for each probe is defined as 1 (Wong and Medrano, 2005). PCR cycles were: 95°C for 10 minutes, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds.

Allelic Expression

TaqMan (Life Technologies) FAM- and VIC-labeled genotyping probe and primer sets targeting exonic SNPS in GABRG1 (rs976156, C__8723970_1_), GABRA2 (rs279858, C__2073557_1_), GABRA4 (rs7660336, C__11278069_10), GABRB1 (rs10028945, C__2119811_30), and AKR1C3 (rs12529, C__8723970_1_) were used to examine allelic expression bias of the chr4p12 GABAA cluster. 20µL TaqMan reactions containing 2µL of cDNA from iPSC-derived neural cells or genomic DNA from human fibroblasts were carried out in triplicate using Universal Master Mix II (Life Technologies) and an Applied Biosystems 7500 instrument. ΔCT values were generated as the difference between FAM- and VIC-probes for the iPSC-derived neural cell cDNA samples or heterozygote fibroblast gDNA for each SNP. Consistent with other studies (Lin et al., 2012, Serre et al., 2008), we used a threshold for allelic imbalance as a 50% increase in RNA from one of the two alleles (i.e. ±0.5ΔCT).

Post-mortem human brain datasets

To compare our results from in vitro neural cultures with adult human brain GABAA gene expression in vivo, we examined data from two publically available post-mortem datasets: Brain Cloud and Braineac. For the Brain Cloud sample the microarray gene expression dataset (http://braincloud.jhmi.edu) (Colantuoni et al., 2011) was merged with SNP genotype data for each sample (dbGap dataset phs000417.v2.c1). We selected all adult Caucasian cases age 18–80 yo (mean=43.1) with an RNA integrity number ≥7.0 (mean RIN=8.25), resulting in a sample of n=60. The SNP dataset did not include rs279858, but rather a nearby marker, rs279856, tightly linked to rs279858 in Caucasians (r2=0.91; http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg_v3.php). The Braineac dataset [http://braineac.org/; UK Brain Expression Consortium, (Trabzuni et al., 2011)] consists of microarray gene expression datasets for each of 134 Caucasian subjects together with whole genome SNP data. Donors ranged in age from 16–102 yo (mean=59.0) and RNA samples had an average RIN of 3.85 (range=1–8.5). The Braineac public dataset does not allow the selection of a subset of subjects based on age or RIN. Both rs279858 and rs279856 were reported in this dataset and were in complete LD (r2=1.0).

RNA Sequencing

RNA from 4 wells per neural culture was pooled as input for Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). RINs ranged from 7–9.7, with an average of 8.63. Poly-A selected (n=5) or ribosomal-RNA depleted (n=11) RNA was used to generate randomly primed libraries (200–500 bp inserts). NGS was conducted at the Genomics Core of the Yale Stem Cell Center using Illumina TruSeq Chemistry for library preparation and the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform to generate 100-bp reads (average 44 million reads per sample). Sequence reads were aligned using Bowtie and TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2009) and gene expression levels quantified using Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010) using a computational pipeline in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, UConn-Storrs. Sequence tag reads were aligned to reference human genome hg19 and results normalized for exon length and the total sequence read number for each sample to generate Reads Per Kilobase of exon per Million mapped reads (RPKM).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software v22 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Linear mixed-effects models were used to compare gene expression as a function of genotype or cluster membership to account for biological replicates for a subset of lines (biological replicates were available for 15 lines for qPCR data and 6 lines for RNA sequence data). Analysis was repeated using a single value per donor subject by averaging biological replicates and using t-tests for comparison of group means. Statistically significant contrasts identified using mixed-effects models were also seen using t-tests. Pearson correlations and two-step cluster analysis were used to examine the correlation in expression of GABAA genes and to group samples based on patterns of chromosome 4 GABAA gene expression. One-way ANOVA was used to compare adult brain RNA expression as a function of genotype. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Results

GABRA2 RNA Expression Differs by rs279858 Genotype

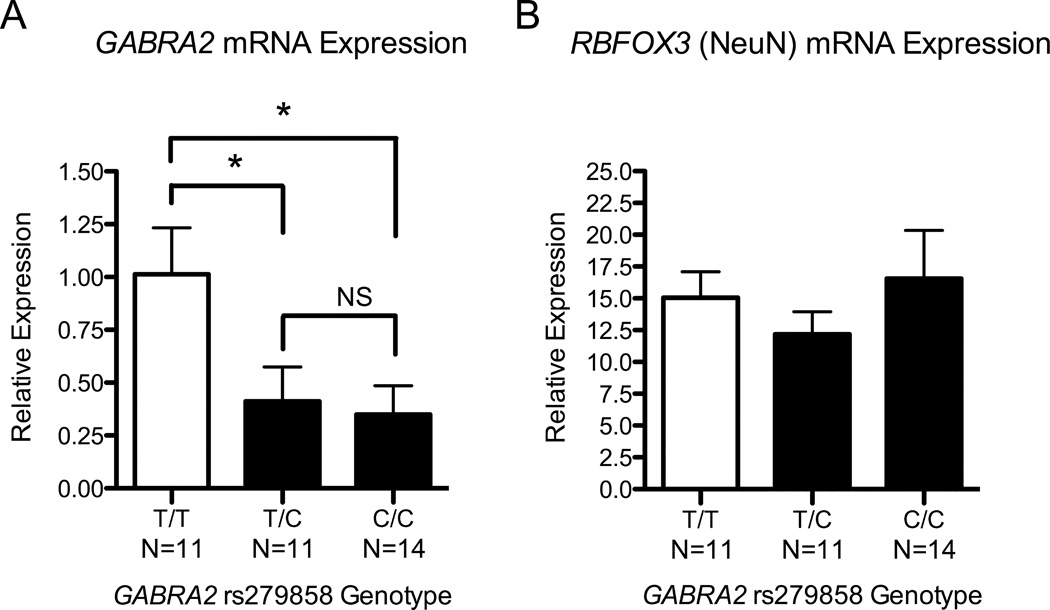

Mixed-effects models examining RT-qPCR GABRA2 RNA levels revealed a significant effect of GABRA2 rs279858 genotype (F=3.7, df=2,15.8, p=0.046). Neural cell cultures derived from rs279858*C-allele donor subjects had lower levels of GABRA2 RNA than T-allele homozygotes, Figure 1A (T/T vs. C/T F=4.9, df=1,20, p=0.039, T/T vs. C/C F=6.1, df=1,12.1, p=0.03, C/C vs. C/T F=0.10, df=1,10.8, p=0.76). In contrast, there was no significant effect of rs279858 genotype on RNA expression of RBFOX3 (Figure 1B, F=0.562, df=2,19.3, p=0.58), which encodes the neuron-specific transcription factor NeuN, suggesting that the between-sample differences in GABRA2 expression were not due to variability in the capacity of iPSC lines to differentiate into neurons.

Figure 1. GABRA2 RNA Expression by rs279858 Genotype.

(A) qPCR data from 36 iPS-derived neural cell lines reveals a significant effect of GABRA2 rs279858 genotype on GABRA2 RNA levels. Expression was significantly lower in rs279858 C-allele carriers than in lines from T/T individuals. (B) There was no difference in RNA expression of RBFOX3 (NeuN) as a function of rs279858 genotype. (* p<0.05)

RNA levels for Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Genes are Correlated and Identify Two Clusters of iPSC Lines

RT-qPCR analysis revealed a significant correlation of RNA expression among the four consecutive chr4p12 GABAA subunit genes (GABRG1, GABRA2, GABRA4, and GABRB1) in iPSC-derived neural cultures (Table 1). This suggests that AD-associated genetic variation in GABRA2 may have regional effects on the expression of all four GABAA subunit genes. There were no correlations between RNA levels for any of the chr4p12 GABAA genes and GABRD (chr1p36, encoding the GABAA δ subunit), or RBFOX3 (chr17q25, encoding NeuN).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Subunit mRNA Expression Levels

|

GABRG1 Chr 4p12 |

GABRA2 Chr 4p12 |

GABRA4 Chr 4p12 |

GABRB1 Chr 4p12 |

GABRD Chr 1p36 |

RBFOX3 Chr 17q25 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABRG1 | 1 | .865** | .727** | .781** | .137 | −.165 |

| GABRA2 | .865** | 1 | .699** | .713** | .109 | −.098 |

| GABRA4 | .727** | .699** | 1 | .748** | .105 | −.061 |

| GABRB1 | .781** | .713** | .748** | 1 | .118 | .033 |

| GABRD | .137 | .109 | .105 | .118 | 1 | .132 |

| RBFOX3 | −.165 | −.098 | −.061 | .033 | .132 | 1 |

p<0.01 (Pearson Correlation, 2-tailed)

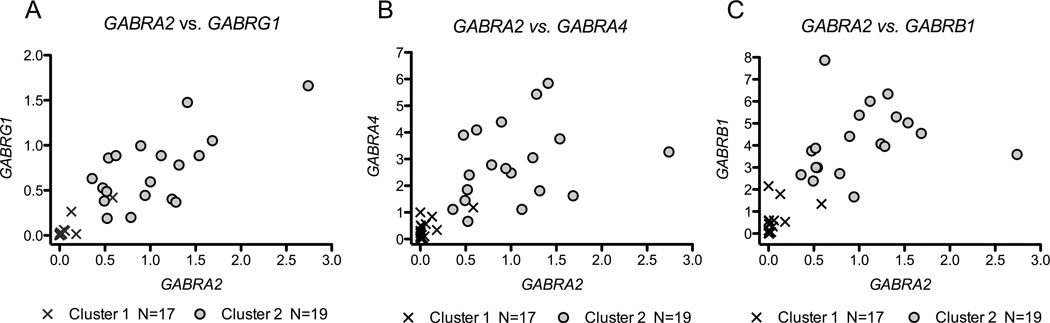

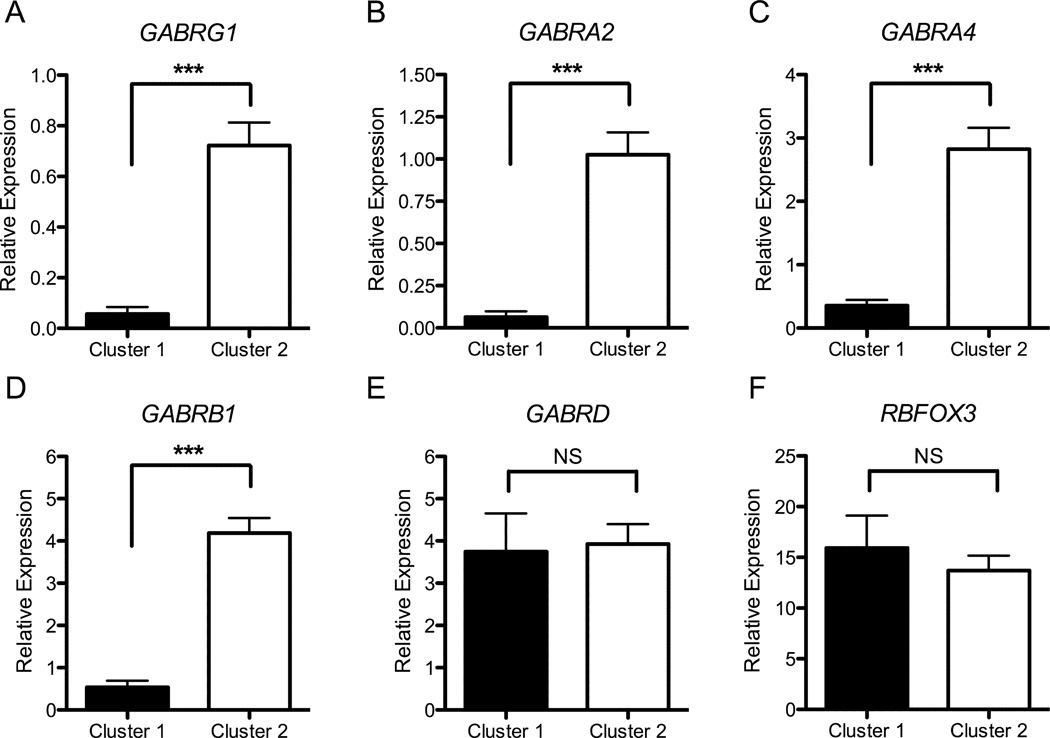

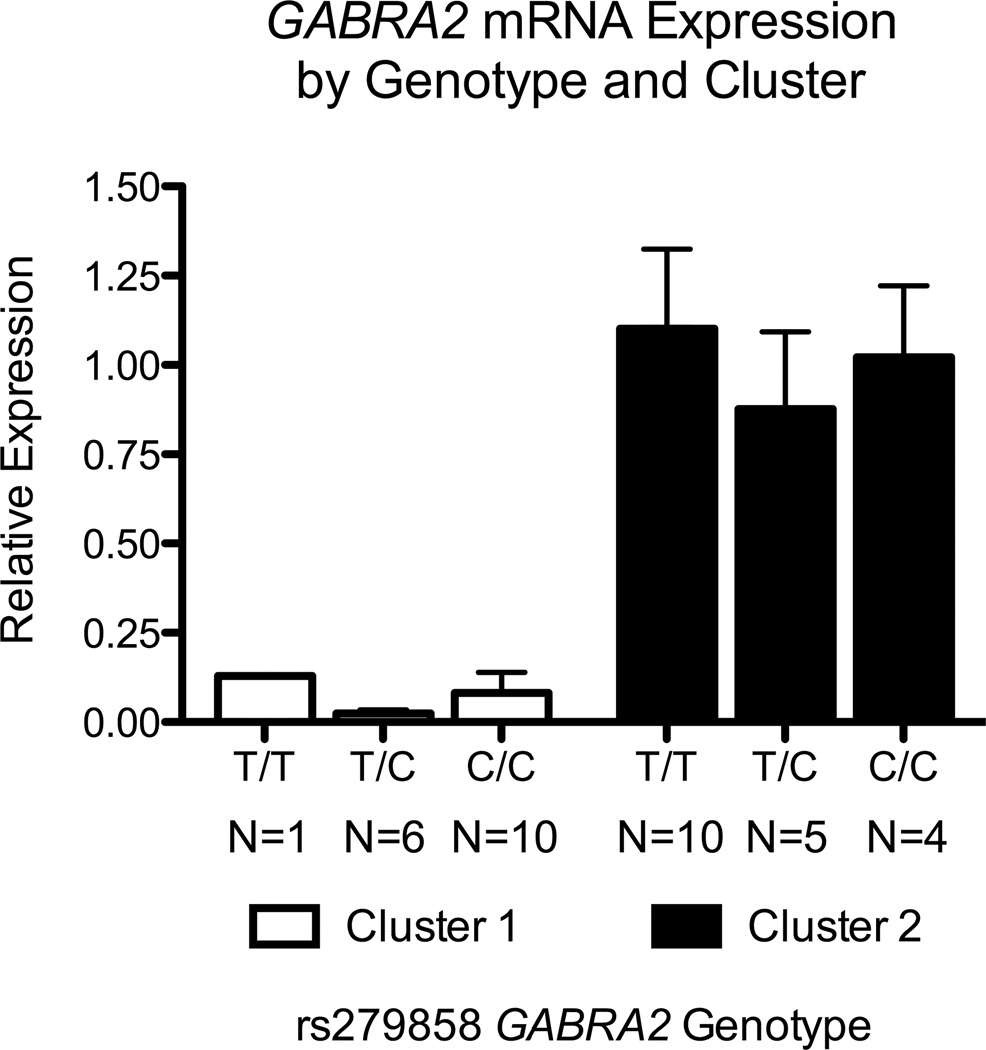

Cluster analysis identified two groups among the 36 neural cell lines: 17 in a low-expression Cluster 1 and 19 in a high-expression Cluster 2. There was a significant association between cluster membership and GABRA2 rs279858 genotype (χ2= 9.9, df=2, p=0.007): Cluster 1 cell lines had a greater frequency of C alleles than those in Cluster 2 (0.76 vs. 0.34; χ2= 12.9, df=1, p=0.003) (Table 2). Scatter plots comparing RNA levels for GABRA2 to those for GABRG1, GABRA4, or GABRB1 RNA, Figure 2, illustrate group differences in chr4p12 GABAA subunit gene expression levels between the two clusters (Figure 2 A–C). Mixed-effects models identified significant differences in RNA expression between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 for each of the chr4p12 GABAA genes (Figure 3 A–D) (GABRG1 F=44.6, df=1,34, p<0.001, GABRA2 F=44.5, df=1,34, p<0.001, GABRA4 F=45.9, df=1,34, p<0.001, GABRB1 F=82.7, df=1,34, p<0.001). There was no between-cluster difference in RNA levels for GABRD (Figure 3E; F=0.034, df=1,30, p=0.86) or RBFOX3 (Figure 3F; F=0.41, df=1,29, p=0.53).

Table 2.

GABRA2 rs279858 Genotype by Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Gene Expression Levels

| GABRA2 rs279858 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster # | Genotype Count (Frequency)a |

Allele Count (Frequency)b |

|||

| C/C | C/T | T/T | C | T | |

| 1 (low expression) | 10 (0.59) | 6 (0.35) | 1 (0.06) | 26 (0.76) | 8 (0.24) |

| 2 (high expression) | 4 (0.21) | 5 (0.26) | 10 (0.53) | 13 (0.34) | 25 (0.66) |

cluster × genotype χ2= 9.9, df=2, p=0.007

cluster × allele χ2= 12.9, df=1, p=0.003

Figure 2. Clustering of Cell Lines by Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Expression in Differentiated Neural Cells.

Scatterplots of qPCR RNA levels contrasting (A) GABRA2 vs. GABRG1, (B) GABRA2 vs. GABRA4, and (C) GABRA2 vs. GABRB1 RNAs for 36 iPS-derived neural cell lines. RNA levels for Cluster 1 cultures (x symbol) were lower for all 4 genes than those for Cluster 2 cultures (gray circles).

Figure 3. RNA Levels for Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Genes by Cluster Group.

RNA levels for chr4p12 GABAA genes measured by qPCR were significantly lower in Cluster 1 cell lines (n=17) than in Cluster 2 cell lines (n=19): (A) GABRG1, (B) GABRA2, (C) GABRA4, and (D) GABRB1. There were no significant differences in RNA levels between clusters for (E) GABRD or (F) RBFOX3 (NeuN). (*** p<0.001)

RNA Sequencing

RNA-Seq data were available from other projects for 10 of the iPS-derived neural cell lines. Sequence data for biological replicates from 6 of these lines were also available (i.e. a subset of iPSC lines were differentiated into neural cells on 2 distinct occasions). Including biological replicates, RNA-Seq data were available for 16 mature neural cultures derived from 10 iPSC lines.

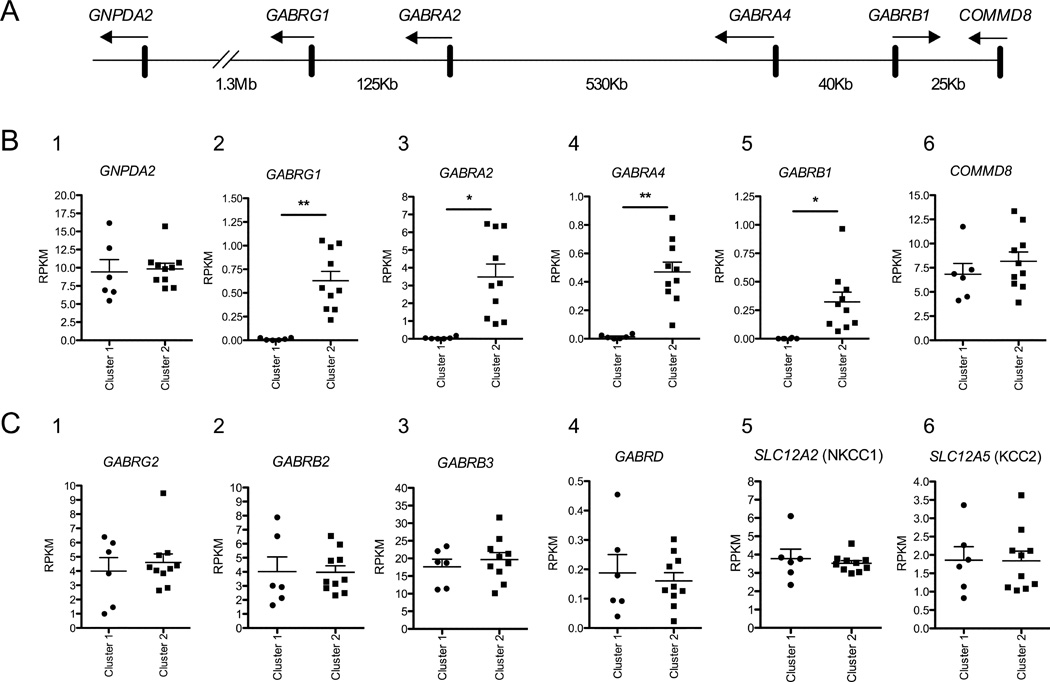

RNA-Seq results confirmed the qPCR findings of lower expression of chr4p12 GABAA genes in neural cell cultures from Cluster 1 vs. Cluster 2 (Figure 4B 2–5) (GABRG1 F=22.2, df=1,7.6, p=0.002; GABRA2 F=7.7, df=1,8.2, p=0.024; GABRA4 F=15.7, df=1,7.8, p=0.004; GABRB1 F=6.0, df=1,8.5, p=0.039). There was no significant difference (p>0.50) in the expression of genes encoding GABAA subunits located on chromosomes 5q34 (GABRG2, GABRB2), 15q12 (GABRB3), or 1p36 (GABRD) (Figure 4C 1–4), or in the expression of the cation-chloride transporters NKCC1 (encoded by SLC12A2) and KCC2 (encoded by SLC12A5) (Figure 4C 5–6), which regulate the intracellular chloride concentration during development and determine whether GABA is an inhibitory or excitatory neurotransmitter (Stein et al., 2004). Similarly, with the exception of GABRA2 and GABRB1 genes, there were no significant differences between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 neural cultures in the level of RNA for a panel of 74 neural patterning genes used by other investigators (Brennand et al., 2014) to compare developmental characteristics of iPSC-derived neural cultures (Supplemental Table 1). These results suggest that the two clusters had a similar degree of neuronal maturation and forebrain lineage features. Interestingly, there was no difference in expression of the two genes directly adjacent to the chr4p12 GABAA cluster, GNPDA2 and COMMD8 (Figure 4B 1 and 6), located ~1.3 Mb and 25 kb from GABRG1 and GABRB1, respectively (Figure 4A). Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that genetic variation in the GABRA2 AD-associated haplotype block influences developmental regulation of the entire cluster of chr4p12 GABAA subunit genes in this iPSC-derived neural culture model. Further, our findings were replicable across multiple neural differentiations of individual iPSC lines, as there were no differences observed in GABAA expression patterns from the iPSC-derived neural cells differentiated on different dates.

Figure 4. RNA-Seq Confirms qPCR Results and Delineates Differences in Expression of Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Genes.

RNA-seq data from16 iPSC-derived neural cell lines generated from 10 donor subjects. (A) Schematic depicting the orientation of the chr4p12 GABAA cluster and adjacent genes. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription, with the approximate distance shown between each gene. (B) There were significant differences in expression between neural cell lines in Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 for the chr4p12 GABAA genes GABRG1; GABRA2; GABRA4; GABRB1, but not for the genes directly adjacent to the chr4p12 GABAA cluster GNPDA2, and COMMD8.)(C) GABAA genes located on other chromosomes did not differ in expression between neural cell lines in Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (GABRG2, GABRB2, GABRB3, GABRD). Genes encoding cation-chloride transporter proteins also did not differ between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (SLC12A2 and SLC12A5). (* p<0.05; ** p<0.005)

Lack of Association of Genotype and GABAA Expression in Adult Post-Mortem Brain

We examined the expression of chr4p12 GABAA genes in a set of 60 adult post-mortem Caucasian brain samples using a whole genome microarray gene expression dataset [http://braincloud.jhmi.edu; (Colantuoni et al., 2011)], merged with SNP array data for each sample (dbGap dataset phs000417.v2.c1). Because rs279858 was not available in the SNP dataset for these samples, we examined 4p12 GABAA gene expression as a function of the GABRA2 intron 4 SNP, rs279856 located 3.3 kb from rs279858 and in near-complete linkage disequilibrium with it (r2=0.91) in Caucasians. There was no significant relationship of rs279856 genotype with GABRA2 RNA expression (F=0.67, df=2,57, p=0.52). Similar results were obtained examining expression data for a collection of post-mortem adult brain samples from 134 subjects of European descent [http://braineac.org/; UK Brain Expression Consortium, (Trabzuni et al., 2011)]. There was no association of rs279858 genotype with GABRA2 RNA expression in either frontal cortex (F=0.43, df=2,124, p=0.65) or hippocampus (F=1.25, df=2,119, p=0.29).

Complex Genetic Regulation of the Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Cluster

When we examined the within-cluster expression of GABRA2 as a function of rs279858 genotype in the set of 36 iPSC-derived neural cultures, we found that expression did not differ by genotype among cell lines within Cluster 1 or 2 (Figure 5). The lack of a gene-dose effect was not unexpected in Cluster 1, given the very low expression phenotype and small variability between lines (Figure 2). In contrast, we expected that an autosomal Mendelian cis- or trans-acting effect of a rs279858-linked functional variant on RNA levels would be observable in Cluster 2 cultures because GABRA2 expression was readily detectable with significant between-sample variation in Cluster 2 lines.

Figure 5. Expression of GABRA2 RNA by rs279858 Genotype in Cluster 1 vs. Cluster 2 Neural Cell Lines.

Cluster 1 iPSC-derived neural cell lines had lower levels of GABRA2 RNA and a greater number of C-allele carriers than Cluster 2 lines, but levels of GABRA2 RNA did not show a rs279858 allele dose effect between cell lines within each cluster.

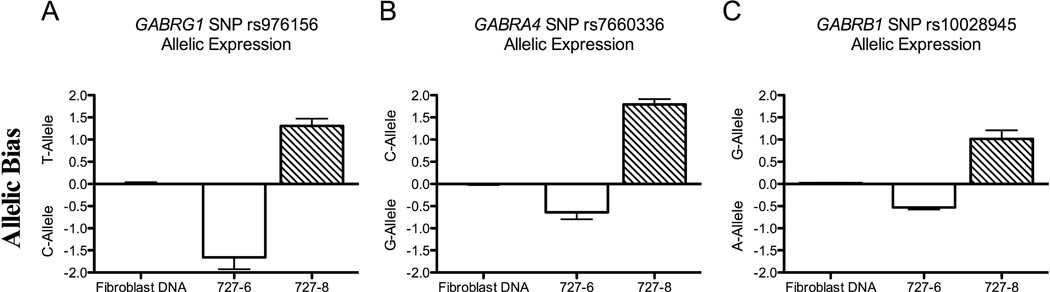

A potential alternative genetic model more consistent with these results would include a cis-acting genetic locus influencing expression of the chr4p12 GABAA gene cluster paired with a random, mitotically-stable, allelic expression bias. In this model, a stochastic clonal allelic expression bias for the chromosome carrying a cis-acting repressive functional variant linked with the rs279858*C-allele would determine Cluster 1 vs. 2 membership for a given iPSC line. Support for a model that includes allelic expression bias in this region was obtained using RT-qPCR and TaqMan allele-specific probes to examine neural cell RNA from 16 Cluster 2 cell lines heterozygous for exonic SNPs in at least one of the chr4p12 GABAA genes (GABRG1, GABRA2, GABRA4 and GABRB1). We observed allelic imbalance [a 50% or greater increase in RNA from one of the two alleles, i.e. >±0.5ΔCT (Serre et al., 2008, Jeffries et al., 2012)] in chr4p12 GABAA RNA expression compared to fibroblast genomic DNA in 7 of 16 lines (44%). In contrast, 0 of 11 lines (0%) heterozygous for an exonic SNP in the AKR1C3 gene (chr10p15) showed an imbalance in expression of the two alleles (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.02). Of the lines that were heterozygous at two or more chr4p12 GABAA genes, 6 of 8 lines displayed concordant allelic expression across markers (i.e., either a greater than ±0.5ΔCT difference for each gene marker or no bias for each gene). Both of the lines that were discordant over the interval displayed allelic bias in 3 of 4 GABAA genes, but with the most distal gene (GABRG1 in one line, GABRB1 in the other line) showing less than a 0.5ΔCT difference. In the case of donor 727 (rs279858*T/T genotype), neural cells differentiated from two independent iPSC clones (727-6 and 727-8) had allelic bias for opposite chromosomes over this region (Figure 6). This is consistent with a random, mitotically-stable clonal event occurring at the time of iPSC generation producing complementary allelic bias in the chr4p12 GABAA genomic interval for the 2 independent iPSC lines from this subject.

Figure 6. Random Allelic Expression Bias of Chromosome 4p12 GABAA Genes in independently derived iPSC-neural cultures from a Cluster 2 Subject.

Allele biased gene expression in mature neural cultures generated from two independently derived iPSC lines (727-6 and 727-8) from a Cluster 2 donor homozygous for the T-allele at GABRA2 rs279858 but heterozygous at exonic SNPs in the other three chr4p12 GABAA genes (rs976156 GABRG1 exon 3 Thr88Thr, rs7660336 GABRA4 3UTR, and rs10028945 GABRB1 3UTR). An opposite pattern of allelic bias (ΔCT between FAM and VIC probes) was observed comparing lines 727-6 and 727-8 for each of the heterozygous SNPs in (A) GABRG1, (B) GABRA4, and (C) GABRB1. Expression of opposite alleles for each gene in the two lines spanning the 4p12 GABAA gene region indicates the presence of a random process during iPSC induction that can produce bias in expression from either the maternal or paternal chromosome.

Discussion

iPSC technologies provide novel model systems to examine the molecular and cellular effects of disease-associated genetic variation using disease-relevant cell types not otherwise readily available. In the current study, we generated neural cultures from 36 iPSC lines derived from 21 donor subjects characterized by rs279858, a synonymous T-to-C polymorphism in exon 5 of GABRA2. Previous research has shown associations between the rs279858*C allele and increased risk for AD (Ittiwut et al., 2012, Enoch et al., 2009, Lappalainen et al., 2005, Bauer et al., 2007, Fehr et al., 2006, Soyka et al., 2008, Li et al., 2014), marijuana and illicit drug dependence (Agrawal et al., 2006), anxiety (Enoch et al., 2006), and differences in the risk of relapse or likelihood of drinking following treatment for substance abuse (Bauer et al., 2012, Bauer et al., 2007). Despite these multiple behavioral associations of GABRA2 variation in humans, the cellular and molecular components underlying the associations are not understood.

We found that relative levels of RNA for the chr4p12 GABAA subunit genes GABRG1, GABRA2, GABRA4, and GABRB1 were significantly inter-correlated in neural cultures derived from iPSC lines. RNA levels for these GABAA subunits identified distinct low-expression and high-expression clusters of cell lines. The low-expression cluster had a higher frequency (0.76 vs. 0.34) of AD-associated GABRA2 rs279858*C alleles than the high-expression cluster. Examination of next-generation RNA–Seq data available for 10 neural cell lines allowed us to extend our analysis to include the expression of GABAA genes located on multiple chromosomes. RNA-Seq data confirmed our qPCR results showing low expression of chr4p12 GABAA genes in cell lines that comprise Cluster 1, and extended our findings by showing that GABAA subunit genes located on other chromosomes showed no difference in expression as a function of expression cluster. Furthermore, transcripts of the GNPDA2 (glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase 2) and COMMD8 (COMM domain-containing protein 8) genes that flank the chromosome 4 GABAA cluster were readily detected in samples in which the four GABAA genes were minimally expressed. Together, these RNA-Seq and qPCR results suggest that the effects of the AD-associated GABRA2 polymorphism on gene regulation are specific for the ~1.4 Mb region containing the chr4p12 GABAA gene cluster.

Our results suggest that the GABRA2 haplotype block containing rs279858 harbors a functional polymorphism with regulatory effects that influence the expression of all four GABAA-subunit genes on chr4p12 in parallel. These results are consistent with other work suggesting the presence of multi-gene locus control elements within the 4p12 and 5q34 GABAA subunit gene clusters. In two independently derived mouse GABRA6 knockout lines, in which neomycin insertion cassettes were used to target exon 8 of GABRA6, expression of the two adjacent genes, GABRA1 and GABRB2, was reduced in the forebrain, suggesting the presence of a locus control element in the chromosome 5q34 GABAA gene cluster (Uusi-Oukari et al., 2000). In addition, human and primate studies provide evidence of a coordinated developmental switch in the relative expression of GABAA subunits (Fillman et al., 2010, Hashimoto et al., 2009).

The lack of association of rs279858 with the expression of chr4p12 GABAA genes in adult post-mortem brain suggests that genetic variation in this region may increase risk for substance-related disease via developmental mechanisms. However, more research is needed to show a developmental influence of chr4p12 variation in vivo. Evidence of genetic variation influencing development but contributing to disease risk in adulthood has been described for the serotonin transporter-linked polymorphic region, 5-HTTLPR of SLC6A4. Carriers of the 5-HTTLPR S-allele are more susceptible to anxiety and depression (Caspi et al., 2010), have reduced functional and white matter connectivity of the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (Pacheco et al., 2009, Pezawas et al., 2005) and show enhanced amygdala activation to fear stimuli (reviewed in (Munafo et al., 2008). In rodents, anxiety- and depression-like behavior in adult mice were only seen when the serotonin transporter was disrupted early in development (Ansorge et al., 2004), suggesting a developmental effect of SLC6A4 genotype on susceptibility to anxiety, depression, and regional brain connectivity in adulthood.

GABAA receptors play key roles in cortical development. Early in development, GABAA receptors are excitatory due to a high intracellular chloride concentration and provide the main excitatory drive onto immature neural cells (Lee et al., 2005). This early excitatory function is important for normal corticogenesis, cell proliferation, and synaptic formation (Wang and Kriegstein, 2009). Because GABAA subunit stoichiometry affects channel properties (Olsen and Sieghart, 2009), we speculate that the genotype-associated differences in GABAA subunit expression may impact GABA signaling effects on cellular connectivity during development. Reported associations of GABRA2 genetic variation with EEG beta frequency oscillations (Edenberg et al., 2004, Lydall et al., 2011), increased activation of the insula (Villafuerte et al., 2012) and nucleus accumbens (Heitzeg et al., 2014) during reward anticipation, and differences in the activation of reward pathways by alcohol cues (Kareken et al., 2010) are consistent with a developmental model of the effects of the AD-associated GABRA2 genetic variant rather than an alteration in ligand binding.

Analysis of RNA expression by RT-qPCR produced two unexpected observations. First, although the rs279858*C-allele was enriched in low expression Cluster 1 cell lines (Table 1), the within-cluster expression of chr4p12 GABAA genes did not differ by GABRA2 genotype (Figure 5). Therefore, the genotypic association with expression level illustrated in Figure 1A reflects the greater frequency of rs279858*C-allele carriers in Cluster 1 vs. Cluster 2 (0.94 vs. 0.47), suggesting that the genetic effect linked to rs279858 strongly determines Cluster membership. The absence of an rs279858 genotype effect within Cluster 2 cell lines suggests that a simple Mendelian genetic model is not sufficient. One model consistent with our results includes a cis-acting genetic locus (in linkage disequilibrium with rs279858) that influences the expression of the chr4p12 GABAA gene cluster together with a recently discovered phenomenon of random clonal allelic-biased expression of a subset of autosomal non-imprinted genes (Chess, 2012). Specifically, we hypothesize that a random stochastic process occurring during the reprogramming of individual fibroblasts to generate iPSC clones results in random allelic bias for the expression of chr4p12 GABAA genes. In this model, iPSC allelic expression bias for the chromosome carrying a cis-acting repressive functional variant linked with the rs279858*C-allele would determine Cluster membership for a given iPSC line.

Autosomal random stochastic inactivation was initially described for a group of immune and nervous system gene families (see Chess, 2012 for review) including immunoglobulins, interleukin receptors, odorant receptors, and neural protocadherin genes. More recent genomic studies have revealed that random mono-allelic expression is widespread and involves a much larger number of autosomal genes (5–20% in mammalian cells) (Gimelbrant et al., 2007, Serre et al., 2008). Mitotically stable, random mono-allelic expression has been demonstrated in clonal lymphoblastoid cell lines (Gimelbrant et al., 2007, Serre et al., 2008), in clonal groups of cells in placental tissue (Gimelbrant et al., 2007), in iPSCs and iPSC-derived neural cultures (Lin et al., 2012), and in human clonal neural stem cells derived from fetal brain and spinal cord (Jeffries et al., 2012). This process typically does not result in exclusively mono-allelic expression but rather clonal lines expressing either one or both alleles at loci showing random clonal allelic bias potential (Gimelbrant et al., 2007, Jeffries et al., 2012). Functional outcomes of allelic bias in the expression of cell surface proteins include the potential for increasing the cellular diversity of immune and neural cells.

A second unexpected observation was the discordance in cluster assignment for pairs of neural cell lines derived from 4 individual donors. The 36 iPSC lines examined included 2 independent iPSC clones from each of 15 donor subjects. Paired lines from 11 donors (9 rs279858 homozygotes and 2 heterozygotes) were concordant (i.e., both lines from a given donor were grouped in the same Cluster), while paired lines from 4 subjects (1 rs279858*T/T, 1 C/C, and 2 T/C) were discordant. We speculate that the AD-associated rs279858*C-allele is in moderate but not complete linkage disequilibrium with an as-yet-unidentified repressive functional variant, and that iPSC-derived rs279858 homozygote neural cells that are discordant in chr4p12 GABAA gene expression are in fact heterozygous for this unidentified functional variant. Allelic bias could then reveal the cis-effect of the functional repressive C-allele linked variant in heterozygotes. Our results demonstrating a modest allelic bias in expression of the entire chr4p12 GABAA gene region (e.g. Figure 6) suggests that allelic bias may partially explain the complex genetic regulatory features in this region.

In summary, we found correlated gene expression of four genes encoding GABAA receptor subunits located in a 1.4 Mb region of chr4p12, with GABAA gene expression levels significantly associated with a tag-SNP for this region that has been linked to AD. The endophenotype of low mRNA expression for the chr4p12 GABAA gene cluster in this iPSC in vitro model may be a more useful marker than the diagnosis of AD to identify functional polymorphisms in this region. Our results suggest that such functional variants may produce behavioral effects relevant to AD via effects on GABAA gene expression in the developing nervous system. This work supports the utility of iPSCs as a model system to explore previously unknown molecular effects of genetic variation associated with risk for neuropsychiatric disease. Limitations of such models include the need to examine multiple donor and iPSC lines to address inter- and intra-cell line variability and the limited ability of cultures to replicate the prolonged and complex development of the human nervous system in vivo. Finally, our finding that nearly half of iPSC lines produce neural cultures with strikingly low levels of expression of the chr4p12 GABAA gene cluster may be of interest to other investigators using this model system to examine neuropsychiatric conditions, particularly if only a limited number of disease and control donor lines are compared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Chris Abreu at the UConn Clinical Research Center Core Lab for assistance in developing subject-specific fibroblast lines. We thank Leann Crandall at the UConn Stem Cell Core for her valued assistance in generating iPSC lines and Mei Zhong at the Genomics Core of the Yale University Stem Cell Center for RNA library preparation and sequencing. Supported by NIH grants P60 AA03510 (Alcohol Research Center), K24 AA13736 (HRK), M01 RR06192 (University of Connecticut General Clinical Research Center) and by a grant from the CT Department of Public Health (JC).

Dr. Kranzler has served as a consultant or advisory board member for the following companies: Alkermes, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Roche. He is a member of the Alcohol Clinical Trials Group of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, which is supported by AbbVie, Alkermes, Ethypharm, Lilly, Lundbeck, and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Author Contribution

RL, HK and JC were responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study. RL was responsible for the acquisition of data. PJ and DGS were responsible for alignment and quantification of RNA sequencing data. RL was responsible for drafting the manuscript. JC and HK provided critical revision of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the content and approved the final version for publication.

References

- Agrawal A, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Bierut LJ, Dunne G, Hinrichs AL, Nurnberger JI, Crowe R, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Dick DM. Association of GABRA2 with drug dependence in the collaborative study of the genetics of alcoholism sample. Behav Genet. 2006;36:640–650. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge MS, Zhou M, Lira A, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Early-life blockade of the 5-HT transporter alters emotional behavior in adult mice. Science. 2004;306:879–881. doi: 10.1126/science.1101678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, Braestrup C, Bateson AN, Langer SZ. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Covault J, Gelernter J. GABRA2 and KIBRA genotypes predict early relapse to substance use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Covault J, Harel O, Das S, Gelernter J, Anton R, Kranzler HR. Variation in GABRA2 predicts drinking behavior in project MATCH subjects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1780–1787. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand K, Savas JN, Kim Y, Tran N, Simone A, Hashimoto-Torii K, Beaumont KG, Kim HJ, Topol A, Ladran I, Abdelrahim M, Matikainen-Ankney B, Chao SH, Mrksich M, Rakic P, Fang G, Zhang B, Yates JR, 3rd, Gage FH. Phenotypic differences in hiPSC NPCs derived from patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess A. Mechanisms and consequences of widespread random monoallelic expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:421–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantuoni C, Lipska BK, Ye T, Hyde TM, Tao R, Leek JT, Colantuoni EA, Elkahloun AG, Herman MM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Temporal dynamics and genetic control of transcription in the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2011;478:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covault J, Gelernter J, Hesselbrock V, Nellissery M, Kranzler HR. Allelic and haplotypic association of GABRA2 with alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;129B:104–109. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covault J, Gelernter J, Jensen K, Anton R, Kranzler HR. Markers in the 5'-region of GABRG1 associate to alcohol dependence and are in linkage disequilibrium with markers in the adjacent GABRA2 gene. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:837–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ, Dick DM, Xuei X, Tian H, Almasy L, Bauer LO, Crowe RR, Goate A, Hesselbrock V, Jones K, Kwon J, Li TK, Nurnberger JI, Jr, O'connor SJ, Reich T, Rice J, Schuckit MA, Porjesz B, Foroud T, Begleiter H. Variations in GABRA2, encoding the alpha 2 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor, are associated with alcohol dependence and with brain oscillations. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:705–714. doi: 10.1086/383283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Albaugh B, Virkkunen M, Goldman D. GABRG1 and GABRA2 as independent predictors for alcoholism in two populations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1245–1254. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Schwartz L, Albaugh B, Virkkunen M, Goldman D. Dimensional anxiety mediates linkage of GABRA2 haplotypes with alcoholism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141:599–607. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr C, Sander T, Tadic A, Lenzen KP, Anghelescu I, Klawe C, Dahmen N, Schmidt LG, Szegedi A. Confirmation of association of the GABRA2 gene with alcohol dependence by subtype-specific analysis. Psychiatr Genet. 2006;16:9–17. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000185027.89816.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillman SG, Duncan CE, Webster MJ, Elashoff M, Weickert CS. Developmental co-regulation of the beta and gamma GABAA receptor subunits with distinct alpha subunits in the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2010;28:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR. Genetics of alcohol dependence. Hum Genet. 2009;126:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0701-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimelbrant A, Hutchinson JN, Thompson BR, Chess A. Widespread monoallelic expression on human autosomes. Science. 2007;318:1136–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1148910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Nguyen QL, Rotaru D, Keenan T, Arion D, Beneyto M, Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA. Protracted developmental trajectories of GABAA receptor alpha1 and alpha2 subunit expression in primate prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzeg MM, Villafuerte S, Weiland BJ, Enoch MA, Burmeister M, Zubieta JK, Zucker RA. Effect of GABRA2 Genotype on Development of Incentive-Motivation Circuitry in a Sample Enriched for Alcoholism Risk. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:3077–3086. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevers W, Luddens H. The diversity of GABAA receptors. Pharmacological and electrophysiological properties of GABAA channel subtypes. Mol Neurobiol. 1998;18:35–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02741459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittiwut C, Yang BZ, Kranzler HR, Anton RF, Hirunsatit R, Weiss RD, Covault J, Farrer LA, Gelernter J. GABRG1 and GABRA2 variation associated with alcohol dependence in African Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:588–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries AR, Perfect LW, Ledderose J, Schalkwyk LC, Bray NJ, Mill J, Price J. Stochastic choice of allelic expression in human neural stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1938–1947. doi: 10.1002/stem.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kareken DA, Liang T, Wetherill L, Dzemidzic M, Bragulat V, Cox C, Talavage T, O'connor SJ, Foroud T. A polymorphism in GABRA2 is associated with the medial frontal response to alcohol cues in an fMRI study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:2169–2178. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Covault J, Feinn R, Armeli S, Tennen H, Arias AJ, Gelernter J, Pond T, Oncken C, Kampman KM. Topiramate treatment for heavy drinkers: moderation by a GRIK1 polymorphism. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:445–452. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen J, Krupitsky E, Remizov M, Pchelina S, Taraskina A, Zvartau E, Somberg LK, Covault J, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, Gelernter J. Association between alcoholism and gamma-amino butyric acid alpha2 receptor subtype in a Russian population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:493–498. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158938.97464.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Chen CX, Liu YJ, Aizenman E, Kandler K. KCC2 expression in immature rat cortical neurons is sufficient to switch the polarity of GABA responses. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2593–2599. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Sulovari A, Cheng C, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J. Association of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor alpha2 gene (GABRA2) with alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:907–918. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman R, Levine ES, Kranzler HR, Abreu C, Covault J. Pilot Study of iPS-Derived Neural Cells to Examine Biologic Effects of Alcohol on Human Neurons In Vitro. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Hrabovsky A, Pedrosa E, Wang T, Zheng D, Lachman HM. Allele-biased expression in differentiating human neurons: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall GJ, Saini J, Ruparelia K, Montagnese S, Mcquillin A, Guerrini I, Rao H, Reynolds G, Ball D, Smith I, Thomson AD, Morgan MY, Gurling HM. Genetic association study of GABRA2 single nucleotide polymorphisms and electroencephalography in alcohol dependence. Neurosci Lett. 2011;500:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani J, Simonini MV, Palejev D, Tomasini L, Coppola G, Szekely AM, Horvath TL, Vaccarino FM. Modeling human cortical development in vitro using induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12770–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202944109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AG, Hoffman EK, Zezza N, Stiffler S, Hill SY. The role of the GABRA2 polymorphism in multiplex alcohol dependence families with minimal comorbidity: within-family association and linkage analyses. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:625–633. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milivojevic V, Feinn R, Kranzler HR, Covault J. Variation in AKR1C3, which encodes the neuroactive steroid synthetic enzyme 3alpha-HSD type 2 (17beta-HSD type 5), moderates the subjective effects of alcohol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:3597–3608. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3614-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Brown SM, Hariri AR. Serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and amygdala activation: a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:852–857. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson E, Bierut LJ. Convergence of genome-wide association and candidate gene studies for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:2086–2094. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABA A receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco J, Beevers CG, Benavides C, Mcgeary J, Stice E, Schnyer DM. Frontal-limbic white matter pathway associations with the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6229–6233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0896-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Hariri AR, Weinberger DR. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nn1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Crestani F, Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor subtypes: dissecting their pharmacological functions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russek SJ. Evolution of GABA(A) receptor diversity in the human genome. Gene. 1999;227:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serre D, Gurd S, Ge B, Sladek R, Sinnett D, Harmsen E, Bibikova M, Chudin E, Barker DL, Dickinson T, Fan JB, Hudson TJ. Differential allelic expression in the human genome: a robust approach to identify genetic and epigenetic cis-acting mechanisms regulating gene expression. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M, Preuss UW, Hesselbrock V, Zill P, Koller G, Bondy B. GABA-A2 receptor subunit gene (GABRA2) polymorphisms and risk for alcohol dependence. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JL, Russek SJ. GABAA receptors: building the bridge between subunit mRNAs, their promoters, and cognate transcription factors. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;101:259–281. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein V, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Jentsch TJ, Hubner CA. Expression of the KCl cotransporter KCC2 parallels neuronal maturation and the emergence of low intracellular chloride. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:57–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabzuni D, Ryten M, Walker R, Smith C, Imran S, Ramasamy A, Weale ME, Hardy J. Quality control parameters on a large dataset of regionally dissected human control brains for whole genome expression studies. J Neurochem. 2011;119:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, Van baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusi-Oukari M, Heikkila J, Sinkkonen ST, Makela R, Hauer B, Homanics GE, Sieghart W, Wisden W, Korpi ER. Long-range interactions in neuronal gene expression: evidence from gene targeting in the GABA(A) receptor beta2-alpha6-alpha1-gamma2 subunit gene cluster. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:34–41. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villafuerte S, Heitzeg MM, Foley S, Yau WY, Majczenko K, Zubieta JK, Zucker RA, Burmeister M. Impulsiveness and insula activation during reward anticipation are associated with genetic variants in GABRA2 in a family sample enriched for alcoholism. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:511–519. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Defining the role of GABA in cortical development. J Physiol. 2009;587:1873–1879. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ML, Medrano JF. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. BioTechniques. 2005;39:75–85. doi: 10.2144/05391RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.