Abstract

Kinetic and spectroscopic studies have shown that the conserved active site residue His200 of the extradiol ring-cleaving homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase (FeHPCD) from Brevibacterium fuscum is critical for efficient catalysis. The roles played by this residue are probed here by analysis of the steady state kinetics, pH dependence, and X-ray crystal structures of the FeHPCD position 200 variants His200Asn, His200Gln, and His200Glu alone and in complex with three catecholic substrates (homoprotocatechuate, 4-sulfonylcatechol, and 4-nitrocatechol) possessing substituents with different inductive capacity. Structures solved at 1.35 –1.75 Å resolution show that there is essentially no change in overall active site architecture or substrate binding mode for these variants when compared to the structures of the wild type enzyme and its analogous complexes. This shows that the maximal 50-fold decrease in kcat for ring cleavage, the dramatic changes in pH dependence, and the switch from ring cleavage to ring oxidation of 4-nitrocatechol by the FeHPCD variants can be attributed specifically to the properties of the altered second sphere residue and the substrate. The results suggest that proton transfer is necessary for catalysis, and that it occurs most efficiently when the substrate provides the proton and His200 serves as a catalyst. However, in the absence of an available substrate proton, a defined proton-transfer pathway in the protein can be utilized. Changes in steric bulk and charge of the residue at position 200 appear capable of altering the rate-limiting step in catalysis, and perhaps, the nature of the reactive species.

Keywords: Oxygen activation, extradiol ring-cleavage, dioxygenase, acid-base catalysis

The FeII-containing extradiol dioxygenases such as homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase from Brevibacterium fuscum (FeHPCD) catalyze aromatic ring cleavage of catecholic substrates with incorporation of both atoms of O2 to yield yellow muconic semialdehyde adducts as products.1-5 The FeII is bound on one coordination face by two His and one Glu/Asp ligands from the protein and on the opposite face by three water molecules.6-8 X-ray crystallographic and spectroscopic studies have shown that the catecholic substrates chelate the FeII opposite the two histidine ligands by displacing two solvents.7-10 This has the effect of releasing or weakening the binding of the third solvent opposite the Glu/Asp residue. Small molecules such as O2 or NO can bind in this site, placing them adjacent to the catecholic substrate.7, 9, 11, 12 The second sphere of the active site of Type I extradiol dioxygenases like FeHPCD contains only three invariant residues, including a histidine residue (H200 in FeHPCD) positioned close to the O2 binding site. Histidine is also similarly placed and essential for high activity of Type II ring cleaving dioxygenases. 13-15

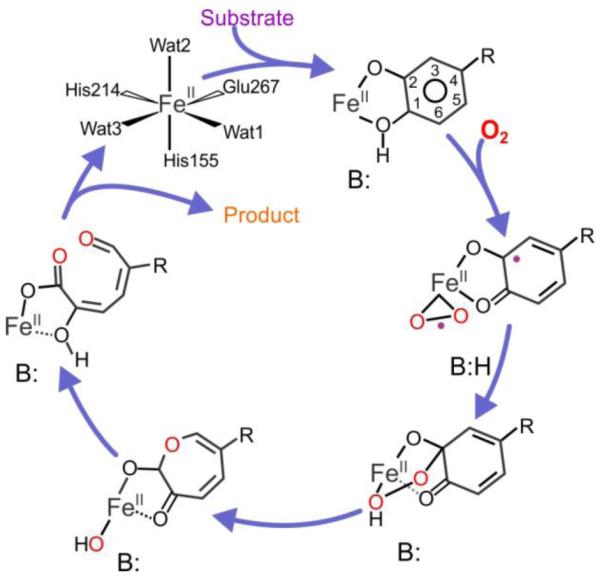

The working model for the mechanism of FeHPCD and related enzymes begins with the sequential binding of the catecholic substrate and O2 to the FeII (Scheme 1).1, 3, 4, 9, 15-21 Net electron transfer from the substrate to the O2 through the FeII would create an adjacent diradical pair, which could undergo recombination to yield an alkylperoxo intermediate. Criegee-like rearrangement of this species would yield a lactone intermediate with the second oxygen from O2 retained on the iron. Subsequent hydrolysis of the lactone by this retained oxygen (at the oxidation state of water) would give the ring-opened product and preserve the dioxygenase stoichiometry.

Scheme 1. Proposed extradiol dioxygenase reaction cyclea.

aThe substrate R-group is −CH2COO− for the native substrate. In this study, alternative substrates with R-groups of −SO3− and −NO2 are also utilized. The acid-base catalyst B: is H200 in FeHPCD.

The substrates for FeHPCD fall into two types. Those like the native substrate homoprotocatechuate (HPCA) bind with only one of the two hydroxyl substituents deprotonated. 10, 22 This type includes slower alternative substrates such as 4-sulfonylcatechol (4SC) with a more electron withdrawing non-hydroxyl substituent.23 The second type of substrate, typified by 4-nitrocatechol (4NC), has strongly electron withdrawing non-hydroxyl substituent(s) and binds with both hydroxyl groups deprotonated. This type is turned over very slowly.2, 12, 17, 24

The salient features of the proposed mechanism in the context of the current study are that: (i) The second proton must be removed from substrates such as HPCA at the C1-OH group to allow formation of the alkylperoxo intermediate (in this study, C1 is defined as the aromatic ring position para to the non-hydroxyl substituent), and (ii) Criegee rearrangement (or a stepwise alternative suggested by computational studies18, 19) would be facilitated by protonation of the bridging oxygen proximal to the iron in the breakdown of the alkylperoxo intermediate. The implied role for an acid/base catalyst in FeHPCD has been assigned to residue H200 and is consistent with past crystallographic, spectroscopic, mutagenic, and kinetic studies.6-8, 12, 13, 25-27 In particular, mutagenesis of H200 to other residues incapable of proton transfer was shown to strongly decrease the rates of steps in the oxygen binding, activation, and insertion portion of the reaction cycle. Moreover, use of these variants led to the stabilization of several intermediates that were not observed in parallel studies with the wild type (WT) enzyme.25-27 The most stable intermediates were observed when 4NC without a protonated catecholic hydroxyl function was used, sometimes resulting in the formation of alternative products. For example, use of the H200N variant and 4NC as the substrate allowed observation of a spin-coupled, nonheme FeIII-superoxo species that slowly decayed to a spin-coupled 4NC-semiquinone-FeIII-(H)peroxo species.26 This species released hydrogen peroxide and 4NC-quinone over the course of several hours without aromatic ring cleavage, but with restoration of the FeII state.

It is important to recognize that changes in the rates of reaction cycle steps and alterations in reaction outcomes upon changes in substrates and mutation of active site residues may result from broad structural changes that have little bearing on catalysis by the native enzyme. Here, the effects of mutagenesis and substrate substitutions on the structure of the FeHPCD active site are evaluated using high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of three enzymes that have H200 substitutions that differ in bulk, charge, and the ability to function as acid-base catalysts. Also, the substrate complexes of each variant with HPCA, 4SC, and 4NC are determined for comparison. It is shown that almost no change occurs in the overall active site structure of FeHPCD for this set of variants and substrates, and thus, they can be used to evaluate the structural basis for the roles played by H200 and substrate in catalysis. The results emphasize the delicate balance that is maintained by the enzyme between electron and proton transfer through control of the interaction of H200 with the substrate and O2. Changes in reaction dynamics and the specific interactions that occur upon disruption of this balance reveal new aspects of the many roles played by substrate and H200 during catalysis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Details of the reagents used, procedures for site-directed mutagenesis, protein expression and purification, and X-ray crystallography experiments are provided in the Supporting Information section.

Steady-state Kinetics

Enzymatic activity of FeHPCD variant enzymes was determined spectrophotometrically by following an increase in absorbance due to formation of the ring-open 5-R-2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde products (5-CHMSA from HPCA and 5-SHMSA from 4SC). The molar extinction coefficients at pH 7.5 used for quantification of the ring-open products of HPCA and 4SC were ε380 = 36 mM−1 cm−1 and ε378 = 20.4 mM−1 cm−1, respectively. For pH dependence studies using HPCA as the substrate, the molar extinction coefficients for protonated (325 nm) and unprotonated (380 nm) forms of 5-CHMSA were determined as a function of pH. Extradiol ring-cleavage reactions (WT, H200E, H200N) were assayed in the pH range of 5.5 – 9.7 using varied concentrations of HPCA in air-saturated buffers (50 mM MES, MOPS, TAPS and AMPSO) at 20 °C. At each pH value, the apparent kinetic constants, kcat and kcat/KM, were determined from the fit of the initial velocity values after establishment of the steady state at varied concentrations of catecholic substrates and atmospheric concentration of O2 (~ 260 μM) to the expression v0 = kcat [S]/(KM + [S]). The pH dependence of the steady state kinetic parameters for reaction of FeHPCD enzymes (WT, H200E, H200N) was determined from the fit of the apparent kinetic constants, kcat and kcat/KM at each pH value, to the expressions that describe mechanisms with one ionization (Ka) and activities of different protonation forms (Equations 1-2). Here, k is the observed kinetic constant, and kl and kh represent the limiting values at low and high pH extremes, respectively.

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

A nonlinear least-squares analysis using Igor-Pro was performed to fit pH dependencies of kinetic constants, with the fitting weighted by the individual standard deviation errors for kcat and kcat/KM, determined from hyperbolic fits at each pH value.

The steady state kinetic parameters for reaction of Y269F and D272N variants with HPCA at pH 7.5 were determined using a similar approach. Ring-cleavage activity of 4NC by Y269F and D272N variants and dissociation constants for 4NC complex were determined using previously described methods.17 All reactions with Y269F and D272N variants were carried out in 200 mM MOPS, pH 7.5 at 22 °C.

RESULTS

Active Site Variants

Three active site variants, H200E, H200Q and H200N, were selected to evaluate the roles of H200. These substitutions perturb the second sphere environment by charge, bulk, and polarity. The catecholic substrates with substituents of different chemical properties (HPCA, 4SC, and 4NC) have been used previously in mechanistic and structural investigations directed toward finding reaction cycle intermediates, and as such, are the most relevant substrates for this study.2, 12, 17, 23-28 Although the ring substituents (−CH2COO−, −SO3− and −NO2) differ in electronegativity and alter the ionization properties of the catecholic substrates, these groups are similar in bulk and polarizability. Therefore, it is reasonable to predict that all three substrates will bind in a similar manner with little change in the position of the aromatic ring in the active site, and this is borne out in the structural results presented here.

FeHPCD and the H200X variants show different patterns of activities towards the three substrates. When the optimal substrate (HPCA) and the substrate with moderate substituent electronegativity (4SC) are used, all of the H200X variants and FeHPCD produce the same ring-cleaved products. In contrast, the use of the 4NC with a highly electron withdrawing substituent allows ring cleavage to occur only for the WT enzyme reaction, albeit with a significantly reduced kcat (~1.5 %) relative to that of the optimal substrate.17 All H200X variants catalyzed slow ring oxidation to yield 4NC quinone.25, 26, 29

The steady state kinetic parameters for ring cleavage of HPCA and 4SC substrates at pH 7.5 by the H200X variants are compared with those for FeHPCD in Table 1. The turnover numbers for HPCA by the H200Q and H200N variants are 36 and 23 % of that of the WT enzyme, respectively, whereas a 30-fold reduction is observed for the H200E variant. When 4SC is used as a substrate for FeHPCD, an 80% decrease in turnover number is observed relative to the value for HPCA at pH 7.5. However, in contrast to HPCA, the H200N, H200Q, and H200E variants turnover 4SC with a kcat similar to that observed for FeHPCD. WT and H200X variants all exhibit high Km values for 4SC, leading to low kcat/Km values in comparison to HPCA turnover. The structural studies described below suggest that this may be due in part to non-optimal interactions of sulfonyl moiety with the anion-binding pocket that stabilizes the position 4 substituent, resulting in weak binding.

Table 1.

Comparison of apparent kinetic parameters for reaction of the FeHPCD and H200X variants at pH 7.5a.

| kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (mM−1s−1) | KM (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPCA | |||

| WT | 10.6 ± 0.2 | 620 ± 60 | 17 ± 2 |

| H200Q | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 400 ± 80 | 10 ± 2 |

| H200N | 2.39 ± 0.05 | 240 ± 30 | 10 ± 1 |

| H200E | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 110 ± 10 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| 4-sulfonylcatechol | |||

| WT | 2.16 ± 0.08 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 460 ± 50 |

| H200Q | 1.35 ± 0.04 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 660 ± 60 |

| H200N | 1.92 ± 0.05 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | 250 ± 30 |

| H200E | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 270 ± 8 |

Reactions were carried out in air-saturated 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.5 at 20 °C and analyzed as described in the Experimental Procedures.

Effects of pH on Steady State Turnover

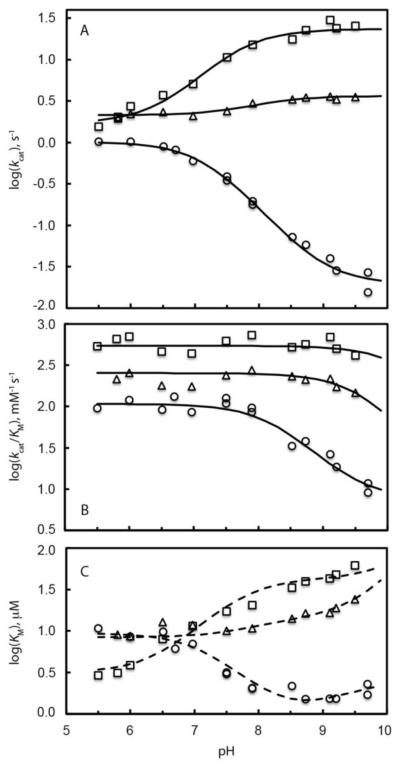

The pH dependencies of kcat and kcat/Km for reactions of WT and H200X variants with HPCA are shown in Figure 1, with fitted parameters summarized in Table 2. For HPCA turnover, kcat for the reaction increases with increasing pH for the WT enzyme, remains unchanged for H200N, and decreases for H200E (Figure 1A). This behavior is mimicked by the Km values (Figure 1C), and as such the kcat/Km ratio is nearly unchanged in the pH range of 5 – 9.5 for WT and H200N (Figure 1B). In contrast, while the kcat/Km ratio is constant for the H200E variant at low pH, it decreases above pH 7.5. The contrasting trends observed for the WT and mutant enzymes using the same substrate suggests that the kinetic changes are related to the ionization state of the altered residue rather than that of the substrate. Furthermore, the insensitivity of the kcat/Km ratio for WT and H200N (and H200E below pH 7.5) suggests that the pH sensitive step occurs after the first irreversible step of the reaction cycle. This is apparently not the case for H200E in the high pH region (see Discussion).

Figure 1.

The pH dependence of apparent kinetic parameters for turnover of HPCA by FeHPCD and H200X variants under saturating concentrations of O2. The apparent kinetic constants kcat (A), kcat/KM (B) and KM (C) for reaction with FeHPCD (□), H200E (○) and H200N (◇) were determined as described in the Experimental Procedures. The solid lines represent fits of the kcat and kcat/KM data at each pH value to the equations that describe mechanisms with a single ionization and activities of different protonation forms (Table 2). The dashed lines represent simulated pH profiles for KM values using fitted parameters of kcat and kcat/KM as a function of pH [log(KM) = log(kcat) – log(kcat/KM)].

Table 2.

Summary of steady-state kinetic parameters kcat and kcat/KM for reaction of FeHPCD, H200E and H200N variants with HPCA as a function of pHa

| Substrate HPCA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Kinetic Constant | Enzyme | Eq. | pKa value | Limiting value(s) |

| kcat (s−1) | WT | (1) | 7.65 ± 0.03 | 1.70 ± 0.06 and 23.3 ± 0.7 |

| H200Nc | (1) | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 2.14 ± 0.04 and 3.6 ± 0.1 | |

| (−)d | NA | 2.8 ± 0.6 | ||

| H200E | (1) | 7.20 ± 0.01 | 1.01 ± 0.02 and 0.0192 ± 0.0004 | |

| kcat/KM (mM−1s−1) | WTb | (2) | 10.3 ± 0.7 | 540 ± 50 |

| (−)d | NA | 570 ± 100 | ||

| H200N | (2) | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 250 ± 20 | |

| H200E | (1) | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 110 ± 10 and 8 ± 4 | |

The data were fitted to the expressions for pH dependence that define a mechanism with single ionization process and activities of different protonation forms, as described in the Experimental Procedures section.

In the experimental pH range, values of kcat/KM were nearly pH-independent, and the pKa value could not be determined accurately.

Values for kcat were essentially pH-independent as evidenced by less than 2-fold difference in limiting values at high and low pH extremes.

An average of all values in the pH range.

Protein Structure Comparisons

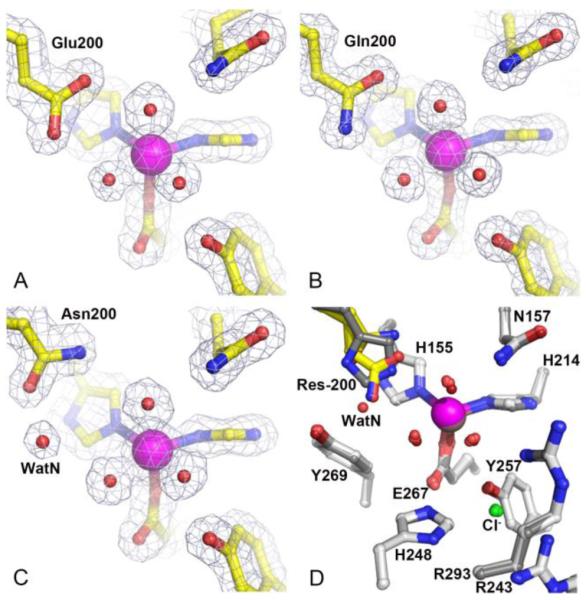

High-resolution X-ray crystal structures of FeHPCD with single active site mutations H200E, H200Q, and H200N were solved at resolutions of 1.65 Å (PDB 4Z6L, Figure 2A), 1.35 Å (PDB 4Z6M, Figure 2B) and 1.52 Å (PDB 4Z6N, Figure 2C), respectively (Table S1-S3). Comparison of the resting state structures of the H200X variants with that of the previously reported WT enzyme (PDB 3OJT) shows that these mutations have no detectable effect on the overall protein structure or on the inter-subunit interactions as indicated by the RMSD values of ~0.5 Å for superposition of all atoms within each tetramer (See an example in Figure 2D). Furthermore, these substitutions of the second sphere residues preserve the same distorted octahedral metal coordination geometry as observed in the FeHPCD structure (Table S4) and do not elicit any conformational changes of the residues in the active site as indicated by RMSD values of 0.15 – 0.44 Å for superposition of all atoms within 15 Å of the metal center. Therefore, structural comparison of the resting state structures of these second sphere mutant enzymes indicates that the observed differences in activity and the type of reaction product formed are likely due to the differences in chemical properties of the side chains and/or the interactions that they support rather than due to the physical alterations in protein structure, global or local.

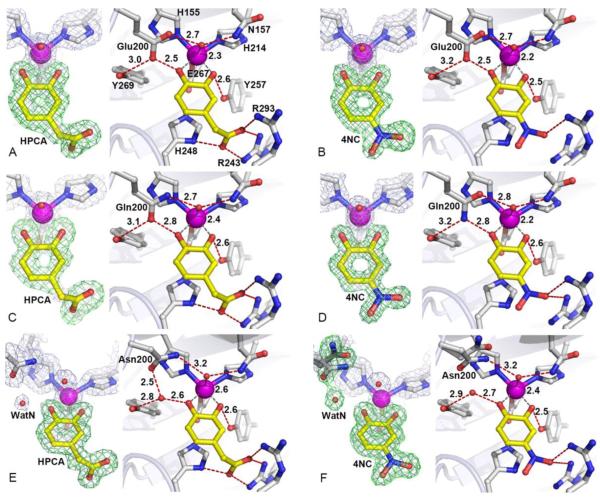

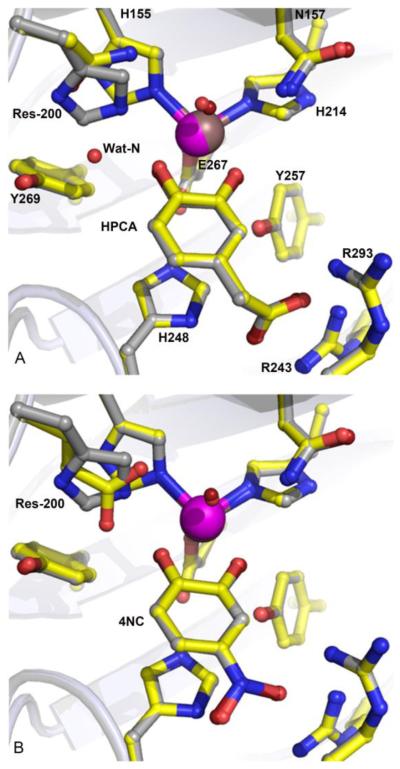

Figure 2.

Resting state structures and comparison of the active site environments for H200X variants with that of FeHPCD. (A) H200E variant (PDB 4Z6L), (B) H200Q variant (PDB 4Z6M) and (C) H200N variant (PDB 4Z6N). (D) Overlay of active site structures of H200X variants and FeHPCD (PDB 3OJT). The blue 2Fobs–Fcalc electron density map is contoured at 1.3 σ (A, C) and 1.4 σ (B). Atom color code: gray, carbon (FeHPCD); yellow, carbon (variant); blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen (variant); dark red, oxygen (FeHPCD); green, chlorine; purple, iron (variant); bronze, iron (FeHPCD). Orientation of carboxamide moiety in the H200Q and H200N variant structures cannot be determined unambiguously based on observed electron density or hydrogen-bonding interactions with neighboring residues.

Interactions and Environment of Second Sphere Residue 200

In the WT enzyme, the environment of the active site places the imidazolium moiety of H200 in the center of the pocket defined by the residues Y269, H155 and W192. Due to these spatial restrictions, the conformational flexibility of H200 side chain is rather limited. In the resting state structures of the WT enzyme, the Nε atom of H200 is 2.8-3.0 Å away from the Fe-bound solvent in the dioxygen binding site, and it is 3.6-3.7 Å away from the solvent in the substrate C1-hydroxyl binding site. In the H200E and H200Q variants, the side chains of residue 200 occupy spatially similar conformations and are brought slightly closer to the metal center, as indicated by the distances of 2.5-2.9 Å and 3.0-3.2 Å to solvent molecules in O2 and substrate C1-hydroxyl binding sites, respectively (Figure 2A-B). In contrast, Asn at position 200 is a spatially different mutation, as the conformational flexibility of this shorter side chain is not restricted by the proximity to the Y269/H155/W192 pocket. An important structural consequence of the Asn at position 200 is a significant increase in the available space at both the O2 and substrate C1-hydroxyl binding sites (Figure 2C). In fact, a new solvent molecule (WatN) is observed in the active site of H200N enzyme, occupying the space created by Asn substitution and hydrogen-bonded to N200, Y269, and solvent in the substrate-C1-hydroxyl site. The relevant hydrogen-bonding distances in the active sites of the WT, H200E, H200Q, and H200N enzymes are given in Table S4.

Interactions of Second Sphere Residues in the ES Complex

Although the analysis of the resting state structures shows that H200E/Q/N variants maintain the same local and global protein structure, the altered residues are expected to have different interactions with the nearby metal-coordinated solvent in the O2 binding site and the aromatic substrate. Accordingly, high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of H200E, H200Q, and H200N variants were solved in complex with HPCA, 4SC, and 4NC substrates (Table S1-S3). To facilitate comparison of substrate binding mode, high-resolution X-ray crystal structure of FeHPCD in complex with 4SC was determined as well (Table S5). High-resolution structures of FeHPCD (PDB 3OJT), FeHPCD-HPCA (PDB 4GHG) and FeHPCD-4NC (PDB 4GHH) have been reported in previous studies.24, 30

The X-ray crystal structures of the H200E-[HPCA] (PDB 4Z6O, Figure 3A), H200E-[4SC] (PDB 4Z6R, Figure S1A) and H200E-[4NC] (PDB 4Z6U, Figure 3B) complexes were solved at 1.63 Å, 1.70 Å and 1.48 Å resolution, respectively (Table S1). Glu at position 200 participates in several interactions with solvent in the O2-binding site, substrate C1-hydroxyl, and Y269 that are reminiscent of those observed for H200, except for the bidentate interaction of the carboxylate moiety that bridges the ligands in two first coordination sphere sites. The hydrogen bonds between residue-200 and the C1-hydroxyl moiety of the aromatic substrates are the strongest for the H200E variant (2.5 Å), suggesting an anionic character for the glutamate (Table S6 – S8) for the HPCA and 4SC complexes. In the case of the H200E-4NC complex, optical spectra show that the 4NC is bound as a dianion.25 Consequently, the Glu200 must be protonated to account for the short distance observed. Interestingly, there is substantial decrease in activity for this mutant with each substrate despite its potential to serve as an acid-base catalyst like the histidine normally in position 200. This decreased reactivity is likely to reflect differences in the protonation state, charge, and rate-limiting step in the pH range of enzymatic activity, which are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 3.

Substrate coordination environments in the active sites of H200X variants. (A) H200E-[HPCA] complex (PDB 4Z6O), (B) H200E-[4-NC] complex (PDB 4Z6U), (C) H200Q-[HPCA] (PDB 4Z6P), (D) H200Q-[4-NC] (PDB 4Z6V), (E) H200N-[HPCA] (PDB 4Z6Q), (F) H200N-[4-NC] (PDB 4Z6W). The blue 2Fobs–Fcalc maps are contoured at 1.0 – 1.4 σ. The green ligand omit Fobs–Fcalc maps are contoured at 4 – 8.5 σ. Atom color code: gray, carbon (enzyme); yellow, carbon (substrate); blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; purple, iron. Red dashed lines show hydrogen-bonds (Å). Gray dashed lines indicate bonds or potential bonds to iron (Å). Cartoons depict secondary structure elements. Representative structures for FeHPCD and H200X variants in complex with 4-SC are shown in Figure S1.

The X-ray crystal structures of the H200Q-[HPCA] (PDB 4Z6P, Figure 3C), H200Q-[4SC] (PDB 4Z6S, Figure S1B) and H200Q-[4NC] (PDB code 4Z6V, Figure 3D) complexes were solved at 1.75 Å, 1.42 Å and 1.37 Å resolution, respectively (Table S2). Spatially, Glu (H200E) and Gln (H200Q) are conservative substitutions and participate in similar interactions. However, the differences in chemical properties of the carboxylate (H200E) and carboxamide (H200Q) moieties are reflected in the strength of hydrogen-bonding interactions towards the C1-OH groups of the substrates (Table S6 – S8).

The X-ray crystal structures of the H200N-[HPCA] (PDB 4Z6Q, Figure 3E), H200N-[4SC] (PDB 4Z6T, Figure S1C) and H200N-[4NC] (PDB 4Z6W, Figure 3F) complexes were solved at 1.57 Å, 1.50 Å and 1.57 Å resolution, respectively (Table S3). The new solvent molecule (WatN) observed in the active sites of the resting state structure of the H200N enzyme (Figure 2C) is also present in the ES complex structures with HPCA and 4NC (Figure 3E and 3F). The occupancy (mobility) of this new solvent (WatN) varies depending on the substrate bound in the active site of H200N variant. For example, the electron density for WatN in H200N-[4SC] is lower than in the other substrate complexes of this variant (Figure S1C), indicating significantly reduced occupancy or increased mobility. On the other hand, the presence of WatN is very well defined in the complex with 4NC (Figure 3F).

In contrast to the H200N structures with HPCA or 4SC bound, the electron density in the active site of the H200N-[4NC] complex clearly indicates that N200 adopts multiple conformations (Figure 3F). One of the N200 conformers is the same as that found in the resting state structure or in the structures of the HPCA or 4SC complexes, forming a hydrogen bond to the new solvent. The second N200 conformer is refined with its carboxamide moiety flipped “out” away from the new solvent. The simultaneous presence of two N200 conformers was observed in all 4 subunits of the H200N-[4NC] complex, with the new flipped “out” conformer refined at occupancies of 50 - 70%. While it is possible that the new “out” conformation is sampled in H200N complexes with other substrates as well, structural analysis shows that in the crystalline form of ES complexes with HPCA and 4SC a single conformation dominates. The distribution of Asn200 conformers in complex with catecholic substrates may be governed by the ionization state of the bound substrate (specifically the protonation state of the C1-OH), which in the case of substrates used in this study, appears to be the only difference in the vicinity of residue 200 in the H200N variant. When dianionic 4NC is bound in the active site of H200N variant, the observed position of new WatN solvent differs from that observed in the resting state or in the H200N-HPCA complex (Figure S2). This shift in position of WatN closer to the coordination sphere may reflect changes in hydrogen bonding interaction with C1-O− of 4NC, and as a consequence the unfavorable steric interaction with N200 conformer in the “in” position (2.3 Å) is relieved in the new flipped “out” conformer (c.f. Table S8 with S4 and S6).

Examples shown in Figure 4A and B illustrate that neither the substrate binding mode nor coordination geometry to the FeII center is altered by the residue substitutions at position 200 (H200E/Q/N). This is consistent with the anion-binding pocket (R243/R293/H248) serving as a primary determinant of the substrate-binding mode by preferential stabilization of the non-hydroxyl substituent of catecholic substrates. The optimal steric and electrostatic stabilization by the anion-binding pocket in FeHPCD is achieved for −CH2COO− moiety of HPCA. However, different substituents at the 4-position can be accommodated in the substrate-binding site, without changes in the positions of the aromatic ring. Although they are shorter, these typically de-localized moieties (−NO2, −SO3−) become polarized and can still interact with the anion-binding pocket,24 albeit with slight out-of-plane distortions.

Figure 4.

Comparison of active sites in the ES complexes of the FeHPCD and H200X variants. (A) Overlayed complexes with HPCA: FeHPCD (PDB 4GHG) and H200N ((PDB 4Z6Q). (B) Overlayed complexes with 4NC: FeHPCD (PDB 4GHH) and H200E (PDB 4Z6U). Atom color code: gray, carbon (FeHPCD); yellow, carbon (H200X); dark blue, nitrogen (FeHPCD); blue, nitrogen (H200X); dark red, oxygen (FeHPCD); red, oxygen (H200X); bronze, iron (FeHPCD); purple, iron (H200X). Cartoons depict secondary structure elements for FeHPCD (gray) and H200X variants (light blue).

Proton Transfer Pathway

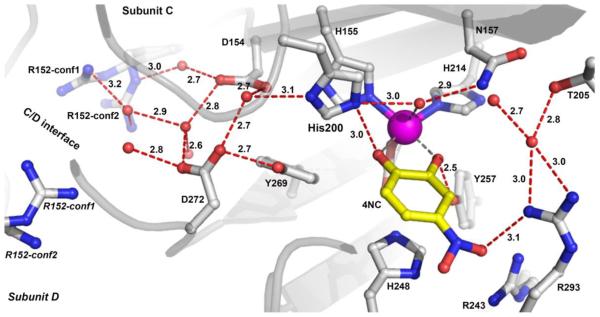

The mechanism illustrated in Scheme 1 invokes a role for H200 as an acid catalyst for the reaction in which the O-O bond is broken. The proton for this function may be supplied by the substrate, or alternatively, it might be supplied from bulk solvent if the substrate is fully deprotonated as is the case for 4NC. Inspection of the structure reveals the potential proton transfer pathway, which connects H200 in FeHPCD to bulk solvent in the intersubunit space (Figure S3) via alternating solvents and ionizable residues (Figure 5). In principle, this pathway will be essential for turnover of 4NC, but not for HPCA, which can supply a proton directly. This is borne out in the case for the FeHPCD enzyme by kinetic experiments with D272N variant, where isosteric replacement of an ionizable residue in the proposed proton relay pathway retains HPCA turnover but completely abolishes ring-cleavage of 4NC, despite presence of H200 in the second sphere (Table 3). In contrast, little effect on ring-cleavage activity for both types of substrates (HPCA or 4NC) is observed for Y269F variant (Table 3), where an “off-pathway” interaction is eliminated by the substitution. In the case of the H200X variants, the envisioned alternate proton relay pathway via Y269 does not lead directly to O2 binding site because the link though H200 is broken. Consequently, ring cleavage is replaced by ring oxidation in the 4NC reaction for H200X variants as observed for the D272N variant.

Figure 5.

Proton transfer pathway in the active sites of the FeHPCD in complex with 4NC (PDB 4GHH, subunit C). Atom color code is the same as that described for Figure 3. Red dashed lines show hydrogen-bonds (in angstroms). Gray dashed lines indicate bonds or potential bonds to iron. Corresponding pathways for complexes in H200E, H200Q and H200N variants are depicted in Figure S4.

Table 3.

Comparison of apparent kinetic parameters for reaction of the Y269F and D272N variants of FeHPCD at pH 7.5a.

| kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (mM−1s−1) | KM (μM) | Kd (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPCA | ||||

| D272N | 2.61 ± 0.04b | 160 ± 20 | 16 ± 2 | |

| Y269F | 6.4 ± 0.5b | 145 ± 25 | 44 ± 7 | |

| 4-NC | ||||

| D272N | < 0.001c,d | 64 | ||

| Y269F | 0.82 ± 0.03b | 40 ± 7 | 19 ± 3 | 31 |

Reactions were carried out in air-saturated 200 mM MOPS, pH 7.5 at 22 °C and analyzed as described in the Experimental Procedures.

Optical spectroscopy shows that the expected ring-cleaved product is produced.

Below limit of detection for ring-cleaved product.

Aerobic incubation over 2 h yields the 4NC quinone product.

DISCUSSION

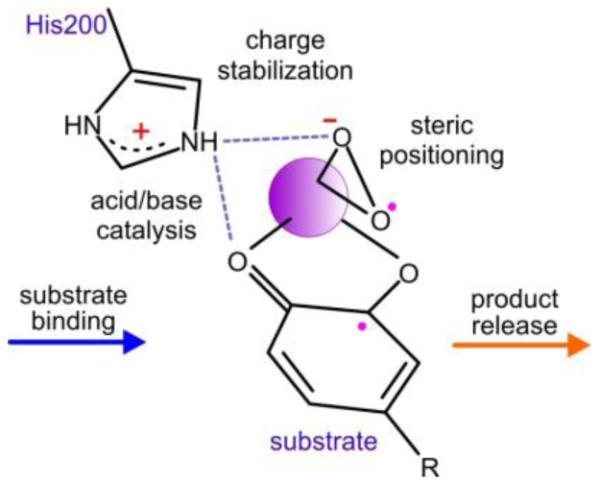

The structural studies described here show that a broad range of substitutions can be made at position 200 in the active site of FeHPCD without causing detectible changes in the positions of the other active site residues. Moreover, several substrates with substituents of very different electronegativity and structure are accommodated without detectable perturbations in the position of the aromatic ring. This is a very favorable outcome for a study designed to evaluate the roles played by substrate and active site residues in the catalytic process. Past kinetic and spectroscopic studies have shown that substrate is far from passive during the oxygen activation and insertion process. It has been speculated that iron-bound substrate can transfer an electron to activate O2 (and simultaneously itself) and provide a proton needed to break the O–O bond in a subsequent step.1, 3, 4, 9, 16-19 Similarly, we have speculated that H200 can play many roles by not only serving as an acid-base catalyst, but also controlling the orientation of bound O2 through its steric bulk, and stabilizing the activated superoxo intermediate through hydrogen bonding and charge compensation.12, 25-27, 31 The studies described here provide insight into the structural basis for how both substrate and H200 perform these various roles. These aspects of the mechanism of extradiol dioxygenases will be discussed in the following sections.

Roles of H200 in Acid-Base Catalysis

The participation of an acid-base catalyst has long been proposed in the O2 activation and insertion mechanism of extradiol dioxygenases, but it was unclear whether this involved one residue serving both roles or two catalytic groups.1, 13 The current and past studies support the role of H200 in one or both roles because exchange of this residue for one incapable of acid-base catalysis significantly alters the rate constants of the reaction steps in which catalytic proton transfer(s) between substrate and bound O2 are proposed to occur.25-27 The kinetic data presented here show strong pH dependence related to the ionization state of the 200-position residue for turnover of the optimal substrate HPCA for enzymes with an acid-base residue in position 200 (WT and H200E). In contrast, kcat is essentially insensitive to proton concentration when a residue incapable of proton transfer is at that position (H200N), as evidenced by less than 2-fold difference in magnitude of kcat at low and high pH extremes. Structural analysis shows that H200 is ideally positioned for proton abstraction from the substrate hydroxyl moiety as well as subsequent transfer of the proton to the dioxygen in the adjacent site. Accordingly, H200 is found to form a strong hydrogen bond (2.5 Å) with the superoxo moiety of the 4NC semiquinone-FeII-superoxo complex trapped previously by conducting the reaction in a crystal of FeHPCD.12 Together, these kinetic and structural results strongly support the role for H200 as both the base and acid catalyst of the reaction cycle. However, the source of the protons for these catalytic events may differ depending on the specific substrate bound in the active site, and this is discussed below.

Role of Substrate in Providing a Proton to H200

Binding of aromatic substrates in the active site is a multi-step process, involving displacement of solvent, substrate ionization, and active site reorganization events to form a reactive state of the enzyme-substrate complex.17, 25 Across the extradiol dioxygenase family, both the native and the rapidly turned over alternative substrates of extradiol dioxygenases become singly deprotonated at the C2-hydroxyl as they bind to the catalytic metal in the active site7, 8, 10, 22 From the structural perspective, the mechanistic advantage of initially retaining a proton on the substrate C1-hydroxyl for extradiol ring cleavage reaction may be at least two-fold. First, the substrate monoanion can serve as a guaranteed source of the required proton optimally placed for base catalysis by H200 in the ternary complex. Second, the dissociation of the C1-hydroxyl proton, which must occur for C2 to become sp3 hybridized during oxygen attack, provides a mechanism to coordinate oxygen activation and alkylperoxo complex formation. This coordination prevents adventitious reactions of activated oxygen, while increasing the efficiency and specificity of ring attack. The slow substrate 4NC presents a quite different case because it binds in the fully deprotonated state,17, 26 and thus it cannot provide a proton. Accordingly, the reaction catalyzed by the WT enzyme is significantly slowed and another proton source is required.32 The structural basis for the supply of this proton provides an intriguing new insight into catalysis by FeHPCD as described in the next section.

Role of H200 in Acid-base Catalysis when the Substrate Cannot Provide a Proton

In contrast to reactions with substrates such as HPCA and 4SC, H200 is absolutely required for ring cleavage of fully deprotonated 4NC. This may indicate that the ability of H200 to readily accept a proton from a source other than substrate near neutral pH is an important aspect of promoting the ring cleavage over ring oxidation chemistry. Indeed, protonation of the proximal oxygen to the Fe is key to O-O bond cleavage in oxygen insertion chemistry.19, 21, 32-34 Analysis of interactions in the active site of FeHPCD reveals a hydrogen-bonding network beginning in the intersubunit space and terminating at H200 that could supply a proton when aromatic substrates such as 4NC cannot (Figure 5). While most of the putative proton pathway is intact in the H200X variants (Figure S4), the lack of His as the terminal residue prevents ring-cleavage of 4NC. This may reflect the more favorable pKa of histidine for acid-base catalysis in this case, or it may be due to unfavorable steric and charge effects of the variants.

The evolutionary rationale for the proposed proton relay pathway in the mechanism of the FeHPCD as means for sourcing a proton other than that supplied by substrate remains unclear. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that FeHPCD and its structural homolog MndD are the only structurally characterized extradiol enzymes that exhibit such an ordered/direct network of functional groups that link to the strictly conserved second sphere acid-base catalyst. Significant variation in composition (enzyme residues and solvents) and lack of order is observed for this region in the other extradiol dioxygenase enzymes for which structural data is currently available.6, 7, 35 Accordingly, FeHPCD and MndD are the only extradiol dioxygenases reported to date to cleave the aromatic ring of 4NC.

Role of Substrate in Providing Protons in the Absence of H200

The fact that ring-open products from the singly deprotonated substrates HPCA and 4SC can be formed by all H200X variants implies that an alternative acid-base catalyst must exist in the enzyme to compensate for lack of H200. One possibility is that the solvent molecules near the active site metal assume this role. The majority of solvent molecules observed within the active site of the resting state structures are displaced upon binding of aromatic substrate. The remaining crystallographic solvent molecules are found in all of the enzyme-substrate structures reported here; these include solvents participating in specific interactions with charged residues within the proposed proton relay pathway and those near the anion-binding pocket (Figure 5 and S4). However, these solvent molecules are located 5 – 8 Å away from the substrate-C1-OH or O2 binding sites, and thus appear not to be well placed as direct substitutes for H200 as the acid-base catalyst. In the H200E and H200Q variants, the steric bulk of the position 200 side chains restrict solvent access to the substrate C1-OH and O2 binding sites (Figures 3A-D and S1A-B). The opposite steric effect is observed for the H200N variant, where the void created by the shorter Asn side chain allows a new crystallographic solvent (WatN) to occupy the second sphere environment, where it is stabilized by hydrogen-bonding interactions with N200, Y269 and substrate C1-OH (Figure 3E-F). If solvent is the alternative catalyst in the H200 variants, WatN in H200N would be expected to make it a better catalyst than either H200E or H200Q. This is observed to be the case in comparison with the H200E variant, but the electrostatic properties of the E200 may contribute strongly to the low activity (Table 1 and 2, Figure 1A) as discussed further in the next section. The expected correlation with solvent accessibility does not appear to be valid, however, for the comparison of the overall activities of the H200N and H200Q variants, which exhibit similar kinetic parameters when turning over HPCA and 4SC. One explanation for this observation is that the steric bulk of H200Q may establish a balance between decreased solvent accessibility and increased stabilization of a reactive intermediate in a productive orientation, another possible role for H200. In contrast, the shorter and more flexible side chain of N200 can assume multiple orientations, none of which is close enough to the O2-binding site to contribute significantly to stabilization of bound dioxygen in the correct orientation for attack on the substrate (Tables S6 – 8). While WatN is properly placed in H200N to act as a base catalyst for substrate deprotonation, it is significantly displaced from the position of H200 and consequently not ideally located to act as an acid catalysis for protonation of the proximal oxygen to the Fe in the alkylperoxo intermediate.

If solvent is not the acid-base catalyst in the absence of H200, the bound oxygen intermediate itself may fulfill this role. Our transient kinetic studies show that addition of O2 to the H200N variant bound with HPCA results in the formation of a relatively long-lived substrate semiquinone-Fe(III)-peroxo species.27 Computational studies suggest that such as species is capable of both abstracting the remaining hydroxyl proton from HPCA and subsequently attacking the substrate to form the alkylperoxo intermediate.34 This reaction is slow and may not represent the reaction coordinate for the native enzyme, but it would result in the same committed alkylperoxo intermediate, and consequently, the same reaction product. In the case of 4NC turnover by the H200X variants, neither the substrate nor the proton transfer pathway can supply the proton to the peroxo moiety. As a result, the peroxo moiety would not attack the substrate and the O-O would not break resulting in the very slow (t1/2 of minutes to hours) observed release of the substrate quinone and peroxide from the enzyme.

Effect of Charge at Position 200

When H200 is substituted by Glu, the magnitude of the turnover number for reaction with the optimal substrate HPCA is maximal in the acidic pH range, opposite to the trend observed for FeHPCD and the other H200 variants (Figure 1). At pH 7.5, the activity of the H200E variant with HPCA is reduced by 30-fold as compared to that of the WT enzyme and also 11-fold as compared to the H200Q enzyme (Table 1). Although, these changes in kcat may reflect the effects on steps other than oxygen activation and reaction, we have reported similar large decreases in rate constants for steps in the oxygen activation steps themselves.25 The fact that significant differences in activity are observed for structurally isosteric substitutions (H200E/Q), suggests that steric interactions alone are unlikely to be the basis for reduced turnover numbers and opposite pH effects.

A more likely cause of the observed kcat effects is the charge on the group at position 200. If H200 functions as the active site base as proposed, then it will gain a positive charge in preparation for the acid catalysis of the Criegee rearrangement. This positive charge in the second sphere environment would stabilize both the deprotonated substrate C1–O− resulting from the base catalysis and the putative superoxo anion radical moiety that would result from electron transfer to O2 as it binds to the iron. Introduction of neutral Gln in position 200 (H200Q) could stabilize one of these anionic species in part by hydrogen-bonding, given the close proximity (2.7 – 2.9 Å) and bidentate interaction of its carboxamide moiety with the first coordination sphere sites. However, introduction of a negatively charged Glu in the second sphere environment (H200E) would disfavor formation and stabilization of the anionic iron-superoxo intermediate, thereby slowing the overall reaction at a key point in the cycle.

The interactions described above are consistent with the crystal structures reported here. Shorter (stronger) hydrogen bonds to substrate C1-OH relative to those in the H200Q variant are consistent with an ionized E200 side chain at pH 7.5 (Table S6 – 8). Aromatic substrates that bind with C1-OH protonated, such as HPCA and 4SC, would be stabilized by interaction with the ionized E200 carboxylate. However, E200 may not be a sufficiently strong base for proton abstraction from substrates such as HPCA and 4SC at neutral pH. In contrast, binding of substrates such as fully ionized 4NC would require that E200 be protonated to prevent charge repulsion with the substrate C1–O−. This proton is evidently either not in the proper location to promote O-O bond cleavage and insertion or transfer of the proton to bound oxygen is inhibited by the resulting creation of a negatively charged residue near the anionic substrate.

Effect of the Position 200 Residue on the Rate-Limiting Step

In addition to an overall slowing of the reaction, H200E exhibits a dramatically different pH dependence than WT or the other H200X variants. Accounting for the pH dependence in a multistep mechanism as found for FeHPCD is often complex because kcat changes may arise from the change in ionization state of one or several important amino acids, or from a change in the rate-limiting step. The rate-limiting step for WT and H200N turnover of HPCA occurs late in the reaction cycle, although the step in which the alkylperoxo intermediate is formed in the case of H200N is only slightly faster and may contribute to the observed kcat.17, 25 This is in accord with the observation that the kcat/Km value is unchanged by pH because this value reflects steps up to and including the first irreversible step,36 which is thought to be O2 binding/reduction when HPCA is the substrate.25 The pH dependence of kcat for the WT enzyme turning over HPCA suggests that a step in the ring opening or product release steps is favored by a neutral histidine. A neutral histidine would also be required for the acid-base role proposed above. The opposite pH effect on kcat of H200E suggests that its pKa is relatively high (e.g. 7.2, Table 2) and that a negative charge slows the rate-limiting step. At pH below 7.5, the constant kcat/Km value for H200E suggests that the rate-limiting step follows the first irreversible step as in the case of the WT and other H200X variants. However, at pH values above 7.5 the decrease in kcat/Km value shows that either the rate-limiting step or a preceding step is affected by pH. It is possible that the negative charge of the Glu in this pH region inhibits the rate of binding of the deprotonated, anionic substrate, shifting the rate-limiting step to this portion of the reaction cycle. If this is the case, then the dramatic difference in pH dependence observed for H200E versus WT enzyme at high pH arises from the impact of the position 200 residue on two different steps of the reaction cycle, neither of which is in the oxygen activation, attack and insertion portion of the reaction cycle. Protonated E200 favors anionic substrate binding, while deprotonated H200 favors anionic product formation and release. These observations reveal additional roles for H200 on the substrate binding and product formation/release portions of the reaction cycle.

Conclusion

As summarized in Scheme 2, the structural studies presented here show that the FeHPCD active site is exactingly organized to allow H200 to abstract a proton from the optimal substrate, stabilize the oxy-complex by both hydrogen bonding and charge interaction, and promote oxygen reaction and insertion by acid catalysis. At the same time, the substrate and oxygen are connected through bonds to the iron that may allow internal transfer of one or two electrons. Perturbations caused by introducing new residues at position 200 or altering the inductive capacity of the substrate substituents cause little or no change in the positions of the substrate or active site amino acid side chains, but significant changes are observed in solvent distributions, the kinetic parameters, and in some cases, the products formed. These results serve to emphasize the exquisitely interconnected nature of the roles played by the components of the active complex. For example, the use of a substrate like 4NC denies H200 the proton needed for catalysis. The reaction can apparently be rescued by histidine protonation via a backup proton relay system, but the reaction remains slow because the electronegative nitro substituent of the substrate prevents efficient transfer of an electron to the metal-oxygen complex. Similarly, substitution of H200 by a residue such as Glu forces the system to use an inefficient acid/base catalyst (solvent, Glu, or Fe(III)-peroxo), and it also introduces a negative charge near where an anionic superoxo species is proposed to form. Again, catalysis is slowed by two different effects, both of which result from the same amino acid change. Finally, efficient enzyme catalysis requires maintenance of high intermediate interconversion rate throughout the catalytic cycle, and a neutral histidine at position 200 appears to be the best choice for the late ring opening and product release steps.

Scheme 2.

Summary of the multiple effects of H200

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Soleil Synchrotron (beamline Proxima I, St Aubin, France), Swiss Light Source (beamline X-06DA, PSI, Villigen, Switzerland), Diamond Light Source (beamlines I-04-1 and I-03, Didcot, UK) and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (beamline ID 14-1, Grenoble, France) for access to synchrotron radiation facilities. We thank Michael Mbughuni for purification of H200X variants, and Marc Cabry for preparation of Y269F and D272N variant plasmids.

Funding

This work is supported by Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/H001905/1 (to E.G.K) and National Institutes of Health Grant GM24689 (to J.D.L.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMPSO

N-(1,1-dimethyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-3-amino-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid

- 5-CHMSA

5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde

- ES

enzyme-substrate complex

- FeHPCD

homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase from Brevibacterium fuscum

- H200X

variants of FeHPCD at position 200 where H is His and X is Asn, Glu, or Gln

- HPCA

homoprotocatechuic acid (3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid)

- MES

4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- MOPS

3-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid

- 4NC

4-nitrocatechol

- 4SC

4-sulfonylcatechol

- 5-SHMSA

5-sulfonyl-2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- TAPS

[(2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl)amino]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- Tris-HCl

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride

- WatN

crystallographically observed solvent in the second coordination sphere of H200N variant

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Additional experimental procedures describing site-directed mutagenesis, protein expression, and purification, production of fully-reduced FeHPCD, and X-ray crystallographic methods, Tables S1 – S8, Figures S1 – S4. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. The coordinates and structure factor files have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [www.rcsb.org/pdb] with accession numbers: 4Z6L, 4Z6O, 4Z6R, 4Z6U, 4Z6M, 4Z6P, 4Z6S, 4Z6V, 4Z6N, 4Z6Q, 4Z6T, 4Z6W and 4Z6Z.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lipscomb JD. Mechanism of extradiol aromatic ring-cleaving dioxygenases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miller MA, Lipscomb JD. Homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase from Brevibacterium fuscum - A dioxygenase with catalase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5524–5535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vaillancourt FH, Bolin JT, Eltis LD. The ins and outs of ring-cleaving dioxygenases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;41:241–267. doi: 10.1080/10409230600817422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bugg TDH. Non-heme iron-dependent dioxygenases: Mechanism and structure. In: de Visser SP, Kumar D, editors. Iron-containing enzymes: Versatile catalysts of hydroxylation reactions in nature. The Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, UK: 2011. pp. 42–66. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Versatility of biological non-heme Fe(II) centers in oxygen activation reactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:186–193. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Han S, Eltis LD, Timmis KN, Muchmore SW, Bolin JT. Crystal structure of the biphenyl-cleaving extradiol dioxygenase from a PCB-degrading pseudomonad. Science. 1995;270:976–980. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Senda T, Sugiyama K, Narita H, Yamamoto T, Kimbara K, Fukuda M, Sato M, Yano K, Mitsui Y. Three-dimensional structures of free form and two substrate complexes of an extradiol ring-cleavage type dioxygenase, the BphC enzyme from Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;255:735–752. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vetting MW, Wackett LP, Que L, Jr., Lipscomb JD, Ohlendorf DH. Crystallographic comparison of manganese- and iron-dependent homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:1945–1958. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.1945-1958.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arciero DM, Lipscomb JD. Binding of 17O-labeled substrate and inhibitors to protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase-nitrosyl complex. Evidence for direct substrate binding to the active site Fe2+ of extradiol dioxygenases. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:2170–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shu L, Chiou YM, Orville AM, Miller MA, Lipscomb JD, Que L., Jr. X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies of the Fe(II) active site of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. Implications for the extradiol cleavage mechanism. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6649–6659. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Arciero DM, Lipscomb JD, Huynh BH, Kent TA, Münck E. EPR and Mössbauer studies of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase. Characterization of a new Fe2+ environment. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:14981–14991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Crystal structures of Fe2+ dioxygenase superoxo, alkylperoxo, and bound product intermediates. Science. 2007;316:453–457. doi: 10.1126/science.1134697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mendel S, Arndt A, Bugg TDH. Acid-base catalysis in the extradiol catechol dioxygenase reaction mechanism: Site-directed mutagenesis of His-115 and His-179 in Escherichia coli 2,3-dihydroxyphenylpropionate 1,2-dioxygenase (MhpB) Biochemistry. 2004;43:13390–13396. doi: 10.1021/bi048518t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sugimoto K, Senda T, Aoshima H, Masai E, Fukuda M, Mitsui Y. Crystal structure of an aromatic ring opening dioxygenase LigAB, a protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase, under aerobic conditions. Structure (London) 1999;7:953–965. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Barry KP, Taylor EA. Characterizing the promiscuity of LigAB, a lignin catabolite degrading extradiol dioxygenase from Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6724–6736. doi: 10.1021/bi400665t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lipscomb JD, Orville AM. Mechanistic aspects of dihydroxybenzoate dioxygenases. Metal Ions Biol. Syst. 1992;28:243–298. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Groce SL, Miller-Rodeberg MA, Lipscomb JD. Single-turnover kinetics of homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15141–15153. doi: 10.1021/bi048690x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Siegbahn PEM, Haeffner F. Mechanism for catechol ring-cleavage by nonheme iron extradiol dioxygenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8919–8932. doi: 10.1021/ja0493805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Deeth RJ, Bugg TDH. A density functional investigation of the extradiol cleavage mechanism in non-heme iron catechol dioxygenases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003;8:409–418. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Machonkin TE, Doerner AE. Substrate specificity of Sphingobium chlorophenolicum 2,6-dichlorohydroquinone 1,2-dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8899–8913. doi: 10.1021/bi200855m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dong G, Shaik S, Lai W. Oxygen activation by homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase: a QM/MM study reveals the key intermediates in the activation cycle. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3624–3635. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vaillancourt FH, Barbosa CJ, Spiro TG, Bolin JT, Blades MW, Turner RFB, Eltis LD. Definitive evidence for monoanionic binding of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl to 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase from UV resonance Raman spectroscopy, UV/vis absorption spectroscopy, and crystallography. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2485–2496. doi: 10.1021/ja0174682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Intermediate in the O-O bond cleavage reaction of an extradiol dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11168–11170. doi: 10.1021/bi801459q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Structural basis for the role of tyrosine 257 of homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase in substrate and oxygen activation. Biochemistry. 2012;51:8755–8763. doi: 10.1021/bi301115c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Groce SL, Lipscomb JD. Aromatic ring cleavage by homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase: Role of His200 in the kinetics of interconversion of reaction cycle intermediates. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7175–7188. doi: 10.1021/bi050180v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mbughuni MM, Chakrabarti M, Hayden JA, Bominaar EL, Hendrich MP, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Trapping and spectroscopic characterization of an FeIII-superoxo intermediate from a nonheme mononuclear iron-containing enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16788–16793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mbughuni MM, Chakrabarti M, Hayden JA, Meier KK, Dalluge JJ, Hendrich MP, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Oxy-intermediates of homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase: Facile electron transfer between substrates. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10262–10274. doi: 10.1021/bi201436n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mbughuni MM, Meier KK, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Substrate-mediated oxygen activation by homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase: Intermediates formed by a tyrosine 257 variant. Biochemistry. 2012;51:8743–8754. doi: 10.1021/bi301114x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Groce SL. Ph.D. thesis. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN: 2003. Mechanistic and mutagenesis studies of homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase; pp. 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fielding AJ, Kovaleva EG, Farquhar ER, Lipscomb JD, Que L., Jr. A hyperactive cobalt-substituted extradiol-cleaving catechol dioxygenase. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011;16:341–355. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0732-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kovaleva EG, Neibergall MB, Chakrabarty S, Lipscomb JD. Finding intermediates in the O2 activation pathways of non-heme iron oxygenases. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:475–483. doi: 10.1021/ar700052v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dong G, Lai W. Reaction mechanism of homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase with 4-nitrocatechol: Implications for the role of substrate. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:1791–1798. doi: 10.1021/jp411812m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Borowski T, Georgiev V, Siegbahn PEM. Catalytic reaction mechanism of homogentisate dioxygenase: A hybrid DFT study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17303–17314. doi: 10.1021/ja054433j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Christian GJ, Ye S, Neese F. Oxygen activation in extradiol catecholate dioxygenases - a density functional study. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1600–1611. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cho J-H, Jung D-K, Lee K, Rhee S. Crystal structure and functional analysis of the extradiol dioxygenase LapB from a long-chain alkylphenol degradation pathway in Pseudomonas. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34321–34330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Northrop DB. On the meaning of Km and V/K in enzyme kinetics. J. Chem. Ed. 1998;75:1153–1157. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.