Abstract

Background

The current study evaluated the roles of drinking motives and shyness in predicting problem alcohol use over two years.

Methods

First-year college student drinkers (N=818) completed assessments of alcohol use and related problems, shyness, and drinking motives every six months over a two year period.

Results

Generalized linear mixed models indicated that shyness was associated with less drinking, but more alcohol-related problems. Further, shyness was associated with coping, conformity, and enhancement drinking motives, but was not associated with social drinking motives. However, when examining coping motives, moderation analyses revealed that social drinking motives were more strongly associated with coping motives among individuals higher in shyness. In addition, coping, conformity, and enhancement motives, but not social motives, mediated associations between shyness and alcohol-related problems over time. Finally, coping motives mediated the association between the interaction of shyness and social motives and alcohol-related problems.

Conclusions

Together, the results suggest that shy individuals may drink to reduce negative affect, increase positive affect, and fit in with others in social situations, which may then contribute to greater risk for subsequent alcohol-related problems.

Keywords: Coping motives, Social motives, Enhancement motives, Conformity motives, Social anxiety

Introduction

Shyness is a common experience of discomfort, awkwardness, inhibition, and evaluation apprehension in the presence of other people (Buss, 1985; Crozier, 1979; Henderson & Zimbardo, 1998; Jones et al., 1986; Zimbardo, 1977). It is similar to social anxiety, but is more prevalent and less severe (Carducci, 1999). Broadly speaking, shy individuals experience similar but less intense, physiological, cognitive, and behavioral elements compared to individuals with social anxiety (Heiser et al., 2003; Ludwig & Lazarus, 1983; Turner & Beidel, 1989). However, shyness is theoretically and empirically distinct from social anxiety (Heckelman & Schneier, 1995). For example, shy individuals report less impairment and fewer avoidant behaviors when compared to those experiencing social anxiety. Thus, shyness differs from social anxiety primarily by degree of severity. It this way, shyness could be viewed as analogous to the distinction between sadness and depression. Interestingly, shyness has received far less attention regarding its association with drinking relative to social anxiety despite the fact that shyness is more common.

Examining shyness, Nelson et al. (2008) found that shy college students reported more internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety, depression, low self-perceptions in multiple domains) and less frequent instances of drinking in comparison to their non-shy peers. Similarly, Bruch et al. (1997) and Bruch et al. (1992) found negative associations between alcohol use and shyness. Among college students, drinking tends to occur in social situations, which might account for this negative association. However, when shy individuals do attend a social event, they might be more likely to drink, either to assuage discomfort or social awkwardness. In fact, although this prediction has not been tested with shyness per se, conceptually related work suggests individuals reporting higher levels of social anxiety report experiencing more negative consequences when they drink (Buckner et al., 2006; Gilles et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2006).

There also is a need to explicate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between shyness and drinking. One such relevant mechanism is motivation for drinking. Specifically, Cooper (1994) outlined four specific motives for drinking, including social, coping, conformity, and enhancement. Social drinking motives consist of drinking to increase one’s enjoyment of a social event. Coping drinking motives are endorsed by individuals who seek to alleviate negative affect by consuming alcohol. Conformity drinking motives involve drinking to fit in with others. Enhancement drinking motives refer to drinking to increase positive emotions and experiences. Social drinking motives are commonly cited among adolescents and young adults and tend to be associated with moderate levels of alcohol consumption (e.g., Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche et al., 2005). Enhancement motives are somewhat less commonly endorsed and are linked with moderate to heavy drinking depending on how they are measured (Kuntsche et al., 2005). Coping motives, on the other hand, are less often endorsed by young adults, yet are associated with more problematic alcohol consumption (e.g., Carey & Correia, 1997; Cooper et al., 1995; Kuntsche et al., 2005). Based upon such work, to manage their shyness, shy individuals may strongly endorse social drinking motives and engage in drinking when they find themselves in social situations. Similarly, shy individuals may be apt to strongly endorse coping motives for drinking to reduce negative affect associated with their shyness. Furthermore, shy individuals may drink to cope with their shyness in social situations. Thus, shy individuals might be more likely to pair social and coping motives because they feel uncomfortable in social situations.

Several studies have specifically considered associations between social anxiety and drinking motives (e.g., Buckner et al., 2006; Clerkin & Barnett, 2012; Ham et al., 2007; Ham et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2006); however, no studies of which we are aware have specifically examined shyness and drinking motives. Past investigations have found associations between social anxiety and related constructs such as anxiety sensitivity and fear of negative evaluation and all four drinking motives. For example, coping and conformity motives have been positively associated with social anxiety and interaction anxiety (Clerkin & Barnett, 2012; Lewis et al., 2008). Similarly, fear of negative evaluation was found to positively correlate with coping, conformity, and social drinking motives (Stewart et al., 2006). The literature has found mixed evidence regarding enhancement motives. Enhancement motives were positively associated with social anxiety in one study (Buckner et al, 2006), yet another study found that enhancement motives were negatively associated with social anxiety (Clerkin & Barnett, 2012).

Furthermore, associations among drinking motives, facets of social anxiety, and alcohol use and related problems have also been explored. Regarding drinking, individuals lower in social anxiety were found to drink more, especially if they more strongly endorsed enhancement drinking motives (Clerkin & Barnett, 2012); whereas coping motives were found to be associated with more drinking and alcohol-related problems, but only for individuals with moderate and high levels of social anxiety (Ham et al., 2007). Coping and conformity motives have been shown to account for associations between fear of negative evaluation, an aspect of shyness, and alcohol-related problems (Stewart et al., 2006). Finally, coping, conformity, and enhancement motives have been found to explain associations between anxiety sensitivity/social anxiety and alcohol-related problems (Buckner et al., 2006; Ham et al. 2009; Lewis et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2001). Thus, social anxiety relates to both drinking motives and alcohol use and related problems. The present investigation aims to extend this literature to include associations among shyness, a more common and less debilitating experience, drinking motives, and drinking and related problems.

Guided by previous research, the present study sought to evaluate associations among shyness, motivations for drinking, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related problems utilizing a longitudinal dataset comprised of five waves of data over a two-year period (Neighbors et al., 2010). We expected that shy individuals who drink would be more likely to drink for social, coping, enhancement, and conformity reasons. Additionally, we expected that social and coping motives would be more strongly associated for shy individuals as they may be drinking to cope with negative affect in social situations to enable them to enjoy a party or social gathering. We further expected that shy individuals would experience more alcohol-related problems, and that associations between shyness and alcohol-related problems would be mediated by drinking motives.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants included 818 undergraduate students from a large northwestern university (57.6% female) who met criteria for heavy drinking, defined as those who reported one or more heavy drinking episodes (4/5 drinks per occasion for women/men, respectively) within the previous month. Participant ages ranged from 17 to 21 (M = 18.1 years, SD = 0.46). The sample consisted of predominately Caucasian/White (65.28%) and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals (24.21%), followed by Other (4.40%), Hispanic/Latino (4.16%), African American/Black (1.47%), and Native American/American Indian (0.49%).

Procedure

Participants completed measures of alcohol use, drinking motives, and alcohol-related problems across five time-points including baseline, six-months, 12-months, 18-months, and 24-months post-baseline. Participants also completed a measure of shyness, which was assessed across four consecutive time-points, beginning with baseline. Students were randomly selected from the campus registrar’s list and screened via email. Eligible students were recruited to the longitudinal trial which was designed to evaluate a personalized normative feedback intervention. Participants were compensated $10 for completing the screening assessment, $25 for completing the baseline assessment, and $25 for completing each of the four follow-up assessments. Retention rates six-, 12-, 18-, and 24-months post-baseline were: 92%, 87%, 85%, and 82% respectively. For complete details regarding the larger trial and procedures, please refer to Neighbors et al. (2010).

Measures

Shyness

The Revised Shyness Scale (Cheek, 1983) assesses the extent to which participants report experiencing feelings related to shyness. The scale consists of 13 items, such as “I feel inhibited by social situations” and “I am often uncomfortable at parties and other social functions. Responses ranged from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale (1=Very uncharacteristic or untrue, strongly disagree; 5=Very characteristic or true, strongly agree). The Revised Shyness Scale has been shown to have sound psychometric properties (Crozier, 2005). Reliabilities for the current study across time points ranged from .87 to .89.

Drinking Motives

The Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQR; Cooper, 1994) consists of 20 items assessing the frequency participants engaged in drinking for differing motives: coping, social, enhancement, and conformity. Each item refers to the question “Below is a list of reasons people sometimes give for drinking alcohol. Thinking of all the times you drink, how often would you say you drink for each of the following reasons?” Sample items include: “because it helps when you feel depressed or nervous” for the coping subscale, “to celebrate a special occasion with friends” for the social subscale, “because you like the feeling” for the enhancement subscale, and “to fit in with a group you like” for the conformity subscale. Responses ranged from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale (1=Never/Almost Never; 5=Almost Always, Always). Reliabilities across time points for coping motives ranged from .83 to .86 and ranged from .84 to .88 for enhancement motives. For social motives, reliabilities ranged from .85 to .91, and for conformity motives, reliabilities ranged from .86 to .88. The DMQ-R has been cited as the most widely used assessment of drinking motives and demonstrates strong psychometric properties (Kuntsche et al., 2005).

Drinking

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985; Kivlahan et al., 1990) was used to measure the number of standard drinks participants consumed each day of the typical week (Monday-Sunday) during the past three months. Typical weekly drinking was assessed by averaging the number of drinks participants reported consuming each week during the three months prior. Considerable use of this measure in the college alcohol literature has shown good test-retest reliability and convergent validity (Neighbors et al., 2006).

Alcohol-related Problems

The Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assesses the extent to which participants had experienced alcohol-related problems in the past month as a result of their drinking or occurring while drinking. The questionnaire included 25 questions such as “neglected your responsibilities” and “felt that you had a problem with school”. Responses ranged from 0 to 4 on a Likert scale (0=Never; 4=10 times or more). Reliabilities across time points ranged from .89 to .96. This measure has been used considerably in college samples and has been demonstrated to reliably identify alcohol-related problems (Martens et al., 2007).

Data analytic plan

Data analysis was conducted using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) approach (Hilbe, 2011). This is a person centered approach which is analogous to standard multi-level models (e.g., Kreft, Kreft, & de Leeuw, 1998; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) with data at multiple levels. Each individual contributed up to five rows of data, where variables at each time point (level 1) are nested within individuals (level 2). The primary difference between GLMM and traditional multi-level models is that distributions may be specified as counts or non-normal. Analyses were completed using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS 9.4 using maximum likelihood estimation and Gauss-Hermite quadrature optimization. Initial analyses were conducted to determine correct distributional specifications for each of the variables used as outcomes (Hilbe, 2011). Model comparisons using BIC values indicated that drinks per week and RAPI scores were best modeled as negative binomial distributions whereas all drinking motives were better approximated by normal distributions. Effect sizes (d) were calculated using the formula 2t/sqrt(df) (Rosenthal, Rosnow, & Rubin, 2000).

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 displays correlations, means, standard deviations, and ranges for all variables at baseline. Correlations revealed that shyness was negatively associated with drinks per week but was not significantly correlated with alcohol-related problems. Shyness was positively associated with coping and conformity motives, was negative associated with enhancement drinking motives, and was not correlated with social drinking motives. Shyness was significantly associated with sex such that males reported higher levels of shyness on average. Alcohol use, as measured by drinks per week, was positively associated with alcohol-related problems, coping, social, and conformity drinking motives, and sex such that men reported consuming more alcohol than women on average. Alcohol-related problems were positively associated with all four drinking motives and with sex such that men reported experiencing more alcohol-related problems than women overall. All drinking motives were positively associated with one another. Sex was associated with conformity drinking motives such that men reported drinking for conformity more so than did women; however sex was not associated with the other three drinking motives.

Table 1.

Correlations, means, standard deviations, and ranges among baseline variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shyness | -- | |||||||

| 2. Drinks per week | −.09* | -- | ||||||

| 3. Alcohol-related problems | .05 | .43*** | -- | |||||

| 4. Social drinking motives | .03 | .17*** | .20*** | -- | ||||

| 5. Coping drinking motives | .18*** | .13*** | .35*** | .34*** | -- | |||

| 6. Conformity drinking motives | .18*** | .03 | .24*** | .39*** | .51*** | -- | ||

| 7. Enhancement drinking motives | −.08* | .28*** | .22*** | .63*** | .29*** | .19*** | ||

| 8. Sex | .08* | .20*** | .09* | .01 | −.02 | .09** | −.01 | -- |

| Mean | 2.44 | 11.65 | 6.91 | 3.47 | 2.04 | 1.80 | 3.31 | 0.42 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.66 | 10.81 | 7.75 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.50 |

| Minimum | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 5.00 | 79.00 | 74.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 |

Note. N = 818

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Primary analyses

In two general linear mixed models (GLMM), we first examined associations between shyness and drinks per week and between shyness and alcohol-related problems. In each GLMM the outcome was specified as a negative binomial distribution. Time and gender were included as covariates. In the first GLMM, shyness was associated with significantly fewer drinks per week, B = −.124, t(2128) = −4.34, p < .001. In the second GLMM, where alcohol-related problems was the outcome variable, drinking was also included as a covariate. Shyness was associated with significantly more alcohol-related problems, B = .135, t(2127) = 3.69, p < .001.

Next, we examined simple associations between shyness and each of the four drinking motives, controlling for time and gender. Given the strong association between drinks per week and drinking motives, we also controlled for typical drinks per week. Results of all four models are presented in Table 2. Results revealed that shyness was uniquely associated with coping, conformity, and enhancement motives, but not social motives.

Table 2.

Drinking motives as a function of shyness controlling for sex, time, and drinking.

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE B | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping motives | Sex | −.08 | .05 | −1.56 | −.11 |

| Time | −.07 | .01 | −7.17** | −.31 | |

| Drinks per week | .01 | .01 | 7.87*** | .34 | |

| Shyness | .19 | .03 | 7.18*** | .31 | |

|

| |||||

| Social motives | Sex | −.04 | .06 | −.61 | −.04 |

| Time | −.10 | .01 | −8.45** | −.37 | |

| Drinks per week | .01 | .01 | 7.24*** | .32 | |

| Shyness | .01 | .03 | 0.12 | .01 | |

|

| |||||

| Conformity motives | Sex | .13 | .05 | 2.55* | .18 |

| Time | −.03 | .01 | −2.97** | −.13 | |

| Drinks per week | .01 | .01 | 2.95** | .13 | |

| Shyness | .20 | .03 | 7.68*** | .33 | |

|

| |||||

| Enhancement motives | Sex | −.02 | .06 | −.42 | −.03 |

| Time | −.12 | .01 | −10.26*** | −.45 | |

| Drinks per week | .02 | .01 | 11.22*** | .49 | |

| Shyness | −.07 | .03 | −2.32* | −.10 | |

Note.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

We then examined drinks per week and alcohol-related problems as a function of shyness and drinking motives controlling for time, gender, and alcohol consumption. Results are presented in Table 3 and reveal independent effects of both drinking motives and shyness (p = .05) in predicting alcohol-related problems after accounting for drinking.1

Table 3.

Alcohol-related problems as a function of shyness and drinking motives, controlling for sex, time, and drinking.

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE B | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol-related problems | Sex | .09 | .06 | 1.53 | .11 |

| Time | −.06 | .01 | −3.99*** | −.17 | |

| Drinks per week | .04 | .01 | 18.08*** | .79 | |

| Shyness | .07 | .04 | 2.10* | .09 | |

| Coping motives | .26 | .03 | 8.25*** | .36 | |

| Social motives | .04 | .03 | 1.47 | .06 | |

| Conformity motives | .10 | .03 | 3.20** | .14 | |

| Enhancement motives | .12 | .01 | 4.25*** | .19 |

Note..

p < .001.

p = .01.

p < .05.

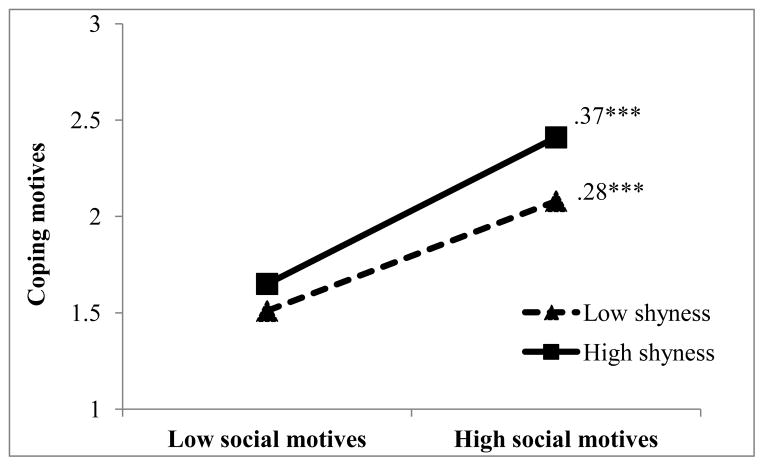

Next, we examined whether social and coping drinking motives were more strongly associated for shy individuals. Table 4 contains parameter estimates for a model examining coping drinking motives as a function of social motives, shyness, and their interaction, controlling for drinking, time, and sex. As can be seen in Figure 1, findings indicate that social motives are positively associated with coping motives, particularly for individuals higher in shyness. Thus, social and coping motives appear to be more closely related for shy individuals, suggesting that they may be using alcohol to alleviate negative affect associated with experiences of shyness in social situations.

Table 4.

Coping drinking motives as a function of sex, time, drinking, social drinking motives, shyness, and the interaction of shyness and social drinking motives.

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE B | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping motives | Sex | −.07 | .05 | −1.42 | −.05 |

| Drinks per week | .01 | .01 | 5.44*** | .19 | |

| Time | −.04 | .01 | −4.18*** | −.15 | |

| Shyness | −.05 | .07 | −.69 | −.02 | |

| Social motives | .15 | .05 | 3.04** | .11 | |

| Social motives*Shyness | .07 | .02 | 3.66*** | .13 |

Note.

p < .001.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Social drinking motives are positively associated with coping drinking motives, especially for individuals higher in shyness, controlling for sex, time, and drinking.

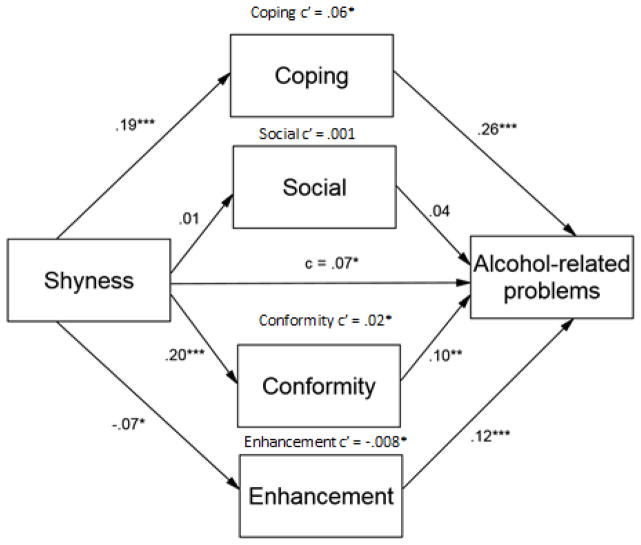

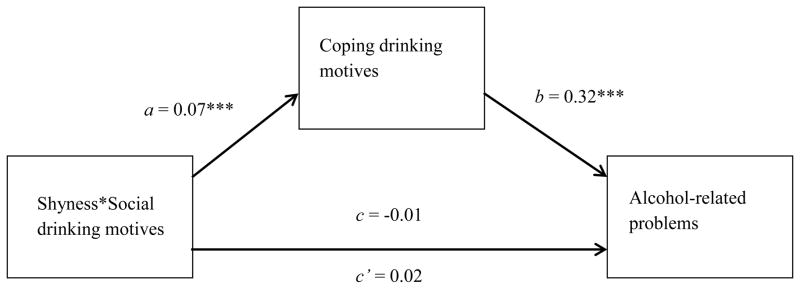

Finally, to test mediation, we used MacKinnon’s ab product approach. Confidence intervals were obtained using the RMediation applet (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011), which provides bootstrapped asymmetric confidence intervals for ab products. For the model evaluating coping motives as a mediator of the association between shyness and alcohol related problems, we used the parameter estimates in Table 2 for specifying the a path, shyness predicting coping, and the b path, coping predicting alcohol-related problems. Thus, the ab product for testing coping motives as a mediator controlled for sex, time, drinking, and social motives. Estimates for the mediation models are unstandardized. As can be seen in Figure 2, results of the RMediation analysis revealed a significant indirect path for coping, ab = 0.061 [95% CI: 0.04, 0.08]. Using the same approach, RMediation results revealed a significant indirect effect of shyness on alcohol-related problems through conformity drinking motives, ab = 0.02 [95% CI: 0.008, 0.034]. Furthermore, the indirect effect of shyness on problems through enhancement motives was also significant, ab = −0.008 [95% CI: −0.016, −0.001]. However, the indirect effect of shyness on alcohol-related problems through social drinking motives was non-significant, ab = 0.001 [95% CI: −0.006, 0.009]. Similarly, RMediation analyses were conducted for a model evaluating an indirect pathway from the interaction between shyness and social motives and alcohol-related problems (controlling for drinking) through coping motives. To obtain parameter estimates for this mediation model, a regression model was run examining alcohol-related problems as a function of shyness and drinking motives as well as the interaction between shyness and social drinking motives, controlling for drinking, time, and gender. Parameter estimates are shown in Table 5. Figure 3 depicts the significant indirect path for coping, ab = 0.022 [95% CI: 0.01, 0.036].

Figure 2.

Coping, conformity, and enhancement motives (but not social motives) mediate associations between shyness and alcohol-related problems controlling for sex, time, and drinking.

Table 5.

Alcohol-related problems as a function of sex, time, drinking, coping drinking motives, social drinking motives, shyness, and the interaction of shyness and social drinking motives.

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE B | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol- related problems | Sex | .11 | .06 | 1.84† | .06 |

| Drinks per week | .04 | .01 | 18.56*** | .65 | |

| Time | −.06 | .01 | −4.21*** | −.15 | |

| Shyness | .07 | .11 | .65 | .02 | |

| Coping motives | .32 | .03 | 12.08*** | .42 | |

| Social motives | .13 | .08 | 1.72† | .06 | |

| Social motives*Shyness | −.01 | .03 | −.02 | −.01 |

Note.

p < .001.

p < .10.

Figure 3.

Coping motives mediate associations between the interaction of shyness and social motives and alcohol-related problems controlling for sex, time, and drinking.

Discussion

The present study examined the associations between shyness, problem drinking, and motives for drinking in a college student sample over a two-year period. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive examination of shyness, motivation for drinking, and drinking outcomes thus far. Results indicated that shyness was negatively associated with drinking, but positively associated with negative alcohol-related consequences across time. As expected, shyness was positively associated with coping and conformity drinking motives over time and was negatively associated with enhancement motives; however, contrary to predictions, shyness was not associated with social drinking motives. Moderation analysis revealed that social and coping drinking motives were positively associated, especially for individuals higher in shyness. Tests of mediation revealed that coping, conformity, and enhancement motives, but not social motives, mediated associations between shyness and alcohol-related problems over time, while controlling for baseline drinking. Finally, coping motives mediated the association between the interaction of social motives and shyness and alcohol-related problems, suggesting that the relationship between social and coping motives for shy individuals is associated with experiencing more alcohol-related problems.

Results supported expectations with one exception. Namely, shyness was not associated with social drinking motives. This finding may be due, in part, to shy individuals being less likely to find themselves in social situations, as has been suggested in examinations of associations between social anxiety and drinking motives and behavior (Buckner et al., 2006). Furthermore, results suggested that social motives may have a different function for shy individuals. Rather than drinking directly for social enjoyment, social drinking motives tend to be more intertwined with coping motives for shy individuals. Specifically, shy individuals who do report drinking for social motives also reporting drinking more to cope, which in turn is associated with more problematic drinking.

The findings have several clinical implications. First, it is increasingly evident that it is important to consider shyness as a vulnerability construct for problem drinking among young adults. Second, for individuals higher in shyness, it is important to assess and potentially intervene to address coping motives for alcohol to help decrease the odds of problem drinking behavior. Psychoeducational information about the nature of shyness, negative affect, drinking behavior and motives, and their cyclical nature may be important. For example, the educational foci could emphasize that drinking does not effectively ameliorate shyness and may increase problems (shyness and drinking) in the longer-term, presumably encouraging further reliance on drinking to cope with distress. Of note, the observed direct effects were moderate in size. Thus, the extent to which clinical relevance of such effects should be understood in the context of their relative magnitude. Also, while the current study was focused on the process of drinking maintenance in examining shyness, alcohol use, drinking motives, and experiences of problems over a two-year period, future investigations may examine how changes in shyness and alcohol-related affect-regulatory processes (expectancies/motives) impact actual drinking behavior in real-time in the laboratory or in clinical administration paradigms or using ecological momentary assessment procedures.

There are several potential limitations to the present study and directions for future research. The present samples were relatively homogeneous in terms of age, race, and education levels. Thus, the degree to which the present results can be generalized to more diverse samples remains to be determined. Second, despite the prospective design, causal inferences cannot be drawn from the existing observational data. Third, the study employed self-report measures to assess the examined variables. Accordingly, method variance may have played a role in the observed effects. Fourth, recall bias may be involved in the reporting of drinking behavior. Future work could more closely space follow-up assessments to help mitigate this concern. Additionally, social anxiety was not assessed so we were not able to statistically control for the influence of social anxiety to determine whether associations were unique to shyness or were due to a commonality among shyness and social anxiety. Finally, we opted a priori to examine the relation between shyness and drinking. Of course, many other substance use behaviors and problems could similarly be explored, including tobacco use and cannabis use, to better contexualize the generalizability of the present models to other forms of substance use behavior.

Overall, the present findings indicate that shyness is associated with more alcohol-related problems and is with positively associated with coping and conformity motives and negatively associated with enhancement drinking motives. Moreover, coping and social drinking motives were more strongly associated among more shy individuals, and coping motives mediated the association between the interaction of shyness and social motives with alcohol-related problems. Finally, coping, conformity, and enhancement motives mediated associations between shyness and alcohol-related problems. Together, the present findings suggest that shy individuals may drink to reduce negative affect associated with shyness in social situations and may also drink to fit in with others in a group setting, which may then contribute to greater risk for subsequent alcohol-related problems.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA014576.

Footnotes

These analyses were also conducted with the added covariate satisfaction with life in predicting drinks per week and alcohol-related problems. Results were similar, shyness significantly predicted drinks per week, with the exception that shyness became marginally significant in predicting alcohol-related problems (p = .06). Inclusion of satisfaction with life as a covariate in the full model did not change associations between any of the motives and alcohol-related problems.

References

- Bruch M, Heimberg R, Harvey C, McCann M, Mahone M, Slavkin S. Shyness, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol use: Discovery of a suppressor effect. J Res Pers. 1992;26:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch M, Gorsky J, Collins T, Berger P. Shyness and sociability reexamined: A multicomponent analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:904–915. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch M, Rivet K, Heimberg R, Levin M. Shyness, alcohol expectancies, and drinking behavior: Replication and extension of a suppressor effect. Pers Indiv Differ. 1997;22:193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner J, Schmidt N, Eggleston A. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behav Ther. 2006;37:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH. Shyness. Springer US; 1986. A theory of shyness; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carey K, Correia C. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek JM. Unpublished manuscript. Wellesley College; Wellesley, MA: 1983. The revised Cheek and Buss shyness scale. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek J, Buss A. Shyness and sociability. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;41:330–339. [Google Scholar]

- Clerkin E, Barnett N. The separate and interactive effects of drinking motives and social anxiety symptoms in predicting drinking outcomes. Addict Behav. 2012;37:674–677. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Parks G, Marlatt G. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psych. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Frone M, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier WR. Measuring shyness: analysis of the revised Cheek and Buss shyness scale. Pers Indiv Differ. 2005;38:1947–1956. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles D, Turk C, Fresco D. Social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and self-efficacy as predictors of heavy drinking in college students. Addict Behav. 2006;31:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham L, Bonin M, Hope D. The role of drinking motives in social anxiety and alcohol use. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham L, Zamboanga B, Bacon A, Garcia T. Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cog Behav Ther. 2009;38:133–145. doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg R, Liebowitz M, Hope D, Schneier F. Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, And Treatment. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser N, Turner S, Beidel D. Shyness: Relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L, Zimbardo P. Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative Binomial Regression. 2. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong A, Galloway C, Feagans L. Coping motives as a moderator of daily mood-drinking covariation. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:344–353. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W, Briggs S, Smith T. Shyness: Conceptualization and measurement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:629–639. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.3.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones WH, Carpenter BN. Shyness. Springer US; 1986. Shyness, social behavior, and relationships; pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan D, Marlatt G, Fromme K, Coppel D, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. J Consult Clin Psych. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, Kreft I, de Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Hove M, Whiteside U, Lee C, Kirkeby B, Oster-Aaland L, Neighbors C, Larimer M. Fitting in and feeling fine: Conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:58–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig R, Lazarus P. Relationship between shyness in children and constricted cognitive control as measured by the Stroop Color-Word Test. J Consult Clin Psych. 1983;51:386–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D, Fairchild A, Fritz M. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens M, Neighbors C, Dams-O’Connor K, Lee C, Larimer M. The factor structure of a dichotomously scored Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:597–606. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens M, Neighbors C, Lewis M, Lee C, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer M. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie J, Hummer J, Lewis M, Lee C, Desai S, Kilmer J, Larimer M. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L, Padilla-Walker L, Badger S, Barry C, Carroll J, Madsen S. Associations between shyness and internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, and relationships during emerging adulthood. J Youth Adolescence. 2008;37:605–615. [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Levenson M. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Read J, Wood M, Kahler C, Maddock J, Palfai T. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow R, Rubin D. Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Morris E, Mellings T, Komar J. Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. J Ment Health. 2006;15:671–682. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Zvolensky M, Eifert G. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;31:157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon D. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behav Res Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S, Beidel D, Townsley R. Social phobia: Relationship to shyness. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:497–505. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, Labouvie E. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo PG. Shyness: What it is, what to do about it. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1977. [Google Scholar]