Abstract

Objective

The current study endeavored to establish the feasibility and acceptability of a brief intervention for medically admitted suicide attempt survivors.

Method

Fifty patients admitted to a Level 1 trauma center were recruited following a suicide attempt. The first 10 patients provided information on what constituted usual care, which in turn informed the creation of the intervention manual and research design. The next 10 patients informed refinement of the intervention and research procedures. The final 30 patients were randomized in a pre-post research design to receive the teachable moment brief intervention plus usual care or usual care only. Patients were assessed prior to randomization and 1 month later by blinded research assistants. Outcomes included patient satisfaction, readiness to change problematic behaviors, reasons for living, and suicidal ideation.

Results

Patients rated the brief intervention as “good” to “great” on all items related to client satisfaction. Significant group × time interactions were observed for readiness to change (β=9.02, S.D.=3.73, P=.02) and reasons for living (β=29.60, S.D.=10.22, P=.004), suggesting greater improvement for those patients who received the brief intervention.

Conclusions

Patients admitted to an acute inpatient medical setting may benefit from a brief intervention that complements usual care by focusing specifically on the functional aspects of the suicide attempt in a collaborative, patient-centered manner.

Keywords: Suicide attempt, Brief intervention, Inpatient medical setting, Longitudinal

1. Introduction

The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention has set a goal of reducing suicide attempts and suicide deaths in the United States by 20% in 5 years and 40% in 10 years [1]. To achieve this goal, prevention strategies must be realistic and sustainable. Interventions intended for high-risk populations [2] must take into account patient, provider, and setting level contextual factors, where new skills are expected to be quickly learned and adopted by care providers, valued by patients, and fit within the culture of specific clinical settings [3]. One such high-risk population is suicide attempt survivors hospitalized in acute care inpatient medical settings, which represent approximately 317,000 hospital admissions and $3.5 billion in total medical costs annually [4]. Previous research suggests significantly elevated rates of suicide (Odds Ratio=56) [5] and subsequent hospitalizations for self-directed violence (Relative Risk=175) [6] for those previously hospitalized for injuries sustained during a suicide attempt. Information is lacking on the emotional impact of treating suicide attempt survivors in hospital settings. Previous studies do indicate that general hospital staff often view patients admitted for self-directed violence in a negative manner compared with clinicians in psychiatric hospital and community settings [7]. As elucidated in a review of emergency staff reactions to suicidal and self-harming patients, implementation of evidence-based approaches may assuage clinician anxiety and negative perceptions when interacting with suicidal patients [8].

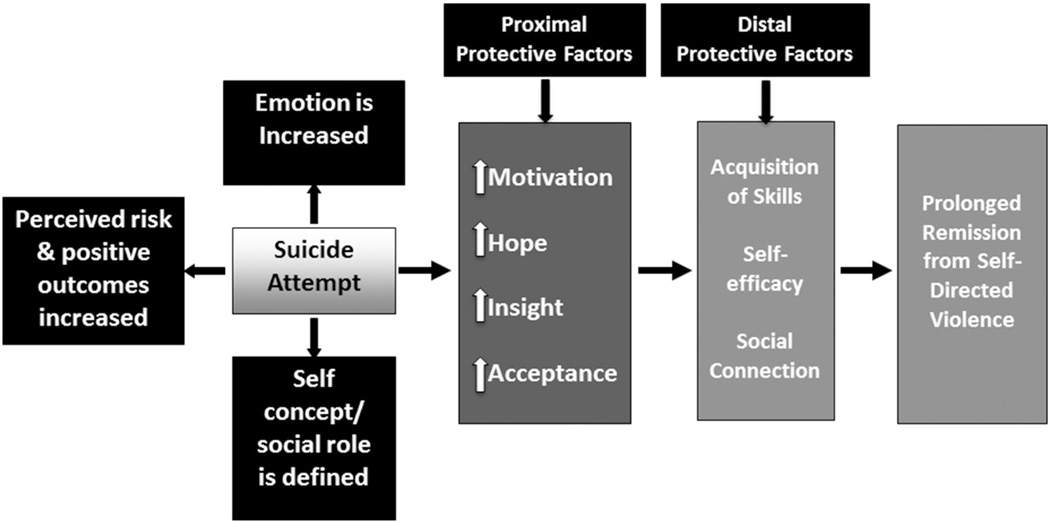

The population of suicide attempt survivors treated in acute inpatient medical settings is heterogeneous in nature, ranging from those who made a non-lethal attempt with little intent to die to others treated for a serious, premeditated suicide attempt meant to result in death. As such, discharge planning will vary based upon multiple factors, including medical coverage, resource allocation, and patient motivation and insight to engage in mental health services. While patients stabilize physically, care providers could take advantage of the time (median= 4 days) [9] spent on medical/surgical floors by engaging them in a brief intervention targeting their suicidal ideation. The timing of such an intervention matches behavioral medicine research supporting a sentinel event effect (i.e., teachable moment), where patients demonstrate greater openness to new information and elevated motivation to reduce problematic health behaviors when engaged shortly after a cueing event [10,11]. As purported by Boudreaux and colleagues [10], the factors associated with short-term behavior change following a cueing event may differ to varying degrees from those factors associated with more distal gains. Following a suicide attempt, proximal factors may include fostering self-acceptance, insight, restoring hope for the future, and increasing motivation to engage in evidence-based treatment to acquire new skills to address the issues that uniquely underlie their recent attempt and suicidal ideation. The distal factors may consist of maintaining adherence to an outpatient suicide-specific treatment plan, strengthening social bonds, and enhancing self-efficacy to create one’s future.

Previous research has applied the conceptualization of a teachable moment to non-suicide related phenomena, such as smoking cessation [11], where the cueing event may be a visit to the emergency department for an exacerbation of a child’s asthma, which in turn leads a parent to forgo future smoking after facing the impacts of second hand smoke. As described by McBride and colleagues [11], a cueing event is associated with a multi-faceted interpretation, which may in turn lead to greater desire to initiate changes in order to reduce problematic health behavior. This conceptual framework can readily be applied to a suicide attempt, which has the potential to increase an individual’s emotional state, sharpen perceptions regarding risks and positive outcomes associated with personal choices, and add clarity to social role and self-concept, such as “I am a spouse, father, and/or son.” The overall perceived impact of the suicide attempt is associated with elevated motivation, hope, insight, and acceptance, which may prove effective in reducing proximal risk during a particularly lethal window of time for suicide when patients are being admitted to inpatient psychiatry units and/or returning to the community [12]. Acquiring new skills through outpatient treatment, enhancing self-efficacy through recovery, and deepening and expanding social connection are theorized to prolong remission from self-directed violence. Thus, intervening on medical/surgical floors may lead to more effective use and engagement in subsequent inpatient and outpatient mental health services to prevent subsequent suicide attempts and emergency services.

The current study aims were informed by the Phase 1a/b treatment development framework described in Leon, Davis and Kraemer [13] wherein we sought to refine and pilot a treatment manual and adherence measure, while also measuring the feasibility and acceptability of screening, recruitment, randomization, and assessment procedures. Additionally, we sought to examine trajectories across 1 month on outcomes of interest between patients who received the brief intervention and those who did not.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty patients medically admitted to a medical/surgical floor of a Level 1 trauma center were recruited following a suicide attempt. Patients admitted for self-directed violence without intent to die (i.e., unintentional overdose, non-suicidal self-injury) or who denied making a suicide attempt were excluded from the study. To better understand usual care for suicide attempt survivors in acute inpatient medical settings prior to beginning the intervention development phase, the first author completed immersive-observation of 10 suicide attempt survivors for up to 8 h per day for two days, which involved separately interviewing patients and their psychiatric care providers. Findings from this initial phase suggest that hospital providers prioritized: a) assessing risk of suicide while in the hospital and during the immediate post-hospitalization period, b) determining whether inpatient psychiatric admission is needed, c) conducting a clinical interview to determine diagnosis and relevant treatment options, and d) providing suggestions on short-term risk management strategies, including medications and behavioral approaches. Notably absent was direct intervention regarding the unique factors underlying and leading up to the recent suicide attempt, such as their beliefs about unburdening others, feelings of isolation, and potential vulnerability to extreme emotion dysregulation. Short-term risk management strategies utilized focused more on keeping the patient safe than addressing what was actually making them suicidal.

The next 10 patients informed the refinement of the initial treatment protocol, adherence rating measure, and study procedures and were not included in the analyses. The next 30 patients were randomized to receive the teachable moment brief intervention plus usual care or usual care only to assess feasibility of the randomization procedure [13], not with the intention of measuring efficacy of the intervention. All study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01355848).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Suicidal ideation and behavior

The Scale for Suicide Ideation is a 19-item assessment used to evaluate the current intensity of the patient’s specific attitudes toward, behavior, and plans to commit suicide. The measure has been the primary outcome measure in several trials targeting suicidal patients and has evidence of strong psychometrics (α=.88) [14]. The Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Count is a brief two-page instrument for determining the first, most recent, and most severe suicide attempt or non-suicidal self-injury. The Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Count also collects information on the date of attempt/self-injury, method used in index and previous attempts according to the definitions of Linehan et al. (e.g., using definitions of self-inflicted injuries which include situations of actual tissue damage and situations where tissue damage would have occurred except for outside intervention or sheer luck [e.g., firearm jammed]) [15], intent to die (i.e., intent to die, ambivalent, no intent to die), highest level of medical treatment received, and lethality [16]. The Reasons for Living Inventory is a measure that rates the importance of different reasons why people choose not to kill themselves. We used the 32-item adolescent version as we attempted to recruit participants as young as 15 years of age, but were unable to consent a minor for the study. Should we have recruited a minor, we believed the adolescent version would have been more appropriate while still providing meaningful information about adults. The measure has shown strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability [17].

2.2.2. Motivation to change

The Stages of Change Questionnaire is an 18-item measure based on the original, 32- item scale created by McConnaughy, Prochaska, and Verlicer [18]. The measure has shown acceptable levels of internal consistency in an adult sample (α=.75–.87) and predictive validity of response to treatment [19].

2.2.3. Satisfaction ratings

The 8-itemClient Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) is a general measure of individual satisfaction with health and human services that takes 3–8 min to complete. It has been shown to have good internal consistency (α=.83–.93) and good predictive validity [20,21]. Patients are asked to use a 4-point Likert scale (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=excellent) to rate each item.

2.2.4. Demographic characteristics

The Demographic Data Survey was used to collect demographic information, including gender (male, female, and transgender), sexual orientation, marital status, income, ethnicity, and number of family members located within a 50-mile radius [22].

2.3. Intervention: teachable moment brief intervention

The Teachable Moment Brief Intervention (TMBI) is informed by two evidenced-based approaches to suicide prevention: a) the therapeutic philosophy of the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) [23,24]; and b) the functional analysis of self-directed violence inherent in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [25,26]. The therapeutic philosophy of CAMS consists of establishing a collaborative relationship with the patient while focusing directly on the unique factors associated with their suicidal ideation. The functional assessment of self-directed violence in DBT is used to validate a patient’s internal and external motivations underlying a suicide attempt, while simultaneously acknowledging that death may not ultimately have been the sole desire associated with a suicide attempt. The emphasis on collaboration guides the interventionist to lead the patient through a discovery process of the specific factors underlying their suicide attempt when conducting the functional analysis, as opposed to a psychoeducational approach where the therapist is the expert espousing common reasons why people make suicide attempts.

TMBI is overtly non-shaming when discussing the patient’s recent suicide attempt. Instead, the goal is to help the patient identify the factors underlying their suicidal ideation and move more rapidly towards making a decision to reject suicide and actively address the problems that led to their suicide attempt, including engaging in inpatient psychiatric care, when appropriate, and outpatient mental health services to resolve these issues. Additionally, the patient and interventionist complete a one page worksheet documenting the factors identified as underlying their suicidal ideation and a crisis response plan to address both short-term coping strategies and long-term treatment planning. Briefly, the intervention is comprised of rapport building, discovery of factors underlying the suicide attempt through functional assessment, short term crisis planning, and discussion of linkage to outpatient mental health services.

In order to spark greater perception of risks and positive outcomes included in the teachable moment conceptual framework, the functional analysis includes a review of what was lost and gained as a result of the suicide attempt. Again, this is done in a non-judgmental, collaborative manner, but does address serious repercussions, including physical impairments, medical bills, likelihood of inpatient hospitalization, and time away from obligations in the community. This discussion is also intended to elicit a greater awareness of self-concept and social role when identifying how the suicide attempt has impacted those in the patient’s sphere of social support and plans for future living. One example from the study was a patient who discussed how moving it was to wake up intubated in his hospital room following a self-inflicted gunshot to the chest, knowing that he had made the wrong decision about killing himself when he saw his family members looking down on him with tears in their eyes. Speaking directly about such factors may prolong increased emotionality. The intent is that this brief therapeutic experience will culminate in greater hope for the future, self-acceptance, insight, and readiness to engage in forthcoming therapeutic efforts and reconnect with social supports (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model for teachable moments as related to a suicide attempt. The conceptual model for teachable moments as related to a suicide attempt is adapted from work by McBride et al. [11] on smoking cessation.

2.4. Procedures

Eligible patients were identified through referrals from the Adult Psychiatry Consultation Service (APCS) service and through reviews of medical records for patients currently being treated by the APCS. A research team member asked the Attending or Resident from the APCS treating an identified patient whether they believed the patient was eligible for the study and the best timing for approach (i.e., working around imminent surgery, altered mental status). When appropriate for recruitment, a member of the research team approached the patient in their hospital room and introduced the study. Informed consent was obtained from patients who expressed an interest and agreed to participate in the study. The decision to randomize patients is informed by Leon et al [13], wherein we sought to measure randomization as a marker of feasibility for future efficacy trials. Consented patients completed a pre-randomization interview in the hospital and 1-month follow-up interview over the telephone with blinded research assistants. Patients randomized to receive the TMBI were met by the first author in their hospital room on the same day they completed the baseline interview. The second author reviewed selected sessions to develop and rate adherence to the treatment manual. Patients who received the TMBI completed an additional post-intervention instrument in the hospital to measure their satisfaction with the intervention. Regardless of treatment condition, all patients received usual care at the trauma center, which included assessment and management of suicidal ideation by the APCS and assistance in disposition planning, including possible inpatient psychiatry admission and treatment linkage to a clinic in the community.

2.5. Analytic approach

We compared the patient demographic and clinical characteristics, and baseline readiness to change, reasons for living, and suicidal ideation using Fisher exact test for categorical variables or t-test for continuous variables between two groups. Items for the CSQ were individually examined to measure mean scores and standard deviations to reflect the acceptability of the TMBI to patients. A significant difference between the treatment groups was observed for gender, but not for other clinical or demographic characteristics, including history of suicide attempt age, ethnicity, and income (Table 1). Next, linear mixed effects regression models were utilized to measure group by time interactions on measures of readiness to change and reasons for living. A Poisson mixed effects regression was utilized to manage the skewed distribution of the suicidal ideation measure, which is consistent with previous research utilizing the Scale for Suicide Ideation. All mixed effect models included gender due to the imbalance between groups. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1, College Station, TX, USA.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and baseline scores on outcome measures.

| Usual Care (n=15) | TMBI (n=15) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (S.D.) | 39.02 (14.43) | 43.67 (13.13) | .37 |

| Sex | .02 | ||

| Female | 7 | 1 | |

| Male | 8 | 14 | |

| Ethnicity | .31 | ||

| Asian/Asian American | 12 | 12 | |

| Black/African American | 0 | 2 | |

| Native American/American Indian | 1 | 0 | |

| White/Caucasian | 0 | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | 0 | |

| Education | .32 | ||

| Some high school | 3 | 2 | |

| High school/GED | 1 | 3 | |

| Business or technical college | 3 | 2 | |

| Some college | 3 | 7 | |

| College graduate | 3 | 1 | |

| Master’ s degree | 2 | 0 | |

| Income | .85 | ||

| Less than $5000 | 5 | 7 | |

| $5000– $14,999 | 0 | 1 | |

| $15,000– $19,999 | 3 | 1 | |

| $25,000– $29,999 | 2 | 1 | |

| $30,000– $49,000 | 1 | 1 | |

| $50,000 or more | 3 | 3 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| Suicide attempts | .24 | ||

| Mean (S.D.) | 10.21 (18.4) | 4.14 (4.42) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.00 (1.0–9.2) | 2.50 (1.0–5.3) | |

| Readiness to change, mean (S.D.) | 74.33 (11.86) | 69.68 (11.16) | .28 |

| Reasons for living, mean (S.D.) | 123.26 (31.30) | 104.15 (40.66) | .16 |

| Scale for suicidal ideation, mean (S.D.) | 25.85 (6.29) | 25.44 (5.66) | .85 |

Note: Sex, ethnicity, education, and income were analyzed using Fisher exact test; Continuous outcomes were analyzed using t-test.

3. Results

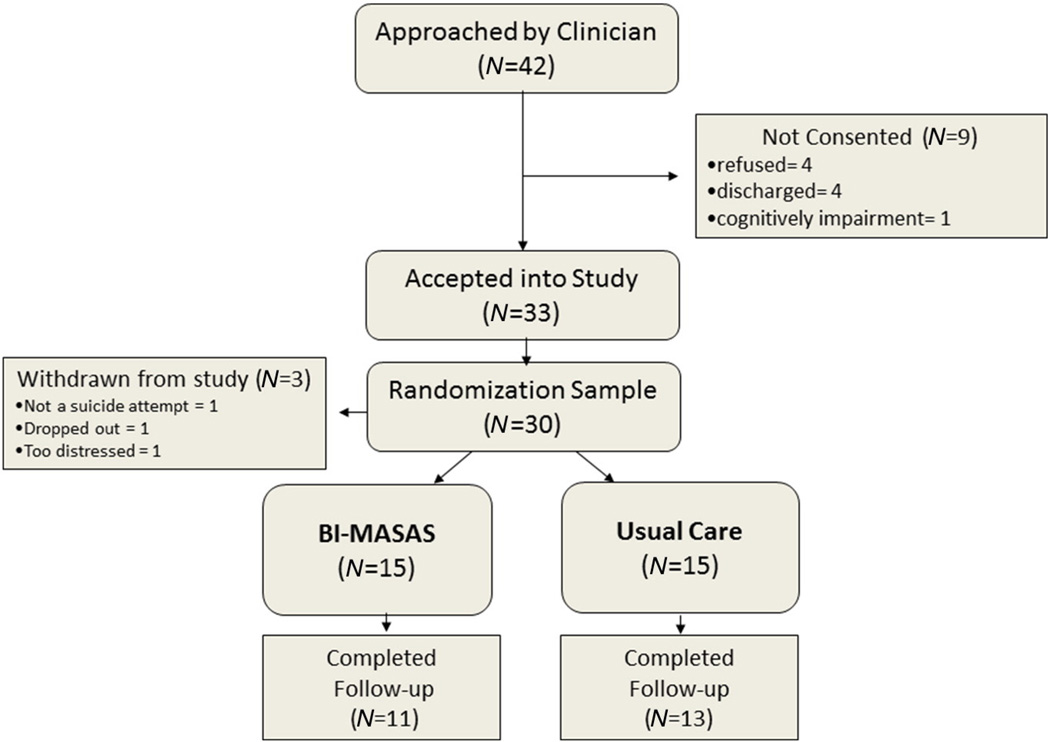

As can be seen in the consort diagram in Fig. 2, we approached 42 participants for the formal pilot phase of the study after the intervention manual and assessment battery were finalized. Four declined to participate, four were discharged prior to informed consent, and one was too cognitively impaired at best mental status to recruit during his hospital stay. Of the 33 participants who consented to the study, we randomized 30 with one determined at baseline not to have attempted suicide, one who dropped out after completing the baseline assessment to concentrate on physical recovery, and one who was too distressed by the baseline interview process. We completed 80% of the 1-month follow-up interviews. The 20% who were lost to follow-up did not respond to our efforts at contacting them through telephone, mail, or email contacts. Review of baseline data demonstrated no significant differences between those who completed the 1-month assessment and those who did not on suicidal ideation, reasons for living, readiness to change, or previous suicide attempts.

Fig. 2.

Consort Chart for Formalized Pilot Study of TMBI vs. usual care. Consort chart for the formalized pilot phase of the TMBI plus usual care vs. usual care. This consort chart only includes patients recruited after the treatment manual, assessment battery, and adherence measures were finalized. The study achieved 80% completion for the 1-month assessment.

3.1. Acceptability ratings

Intervention patients rated the TMBI as “good” to “great” on all CSQ items, with a high overall mean, as well (M=3.38 out of 4, S.D.=0.37). The CSQ was completed immediately after the clinician left the room following the intervention. Written responses were all positive and included sentiments such as “I definitely feel that sitting down and talking with someone early on after a suicide attempt is a good ideas and should be a service” and “At first I wasn’t expecting anything; now I feel like I got a little healed.” The average length of intervention was 43.98 min (S.D.=12.87). One session was not recorded completely due to battery failure on the audio recording device. The usual care condition patients did not complete a CSQ for their care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Client satisfaction ratings for the TMBI.

| Mean (S.D.) | |

|---|---|

| Overall | 3.38 (0.37) |

| Quality of service? | 3.60 (0.51) |

| Get the service you wanted? | 3.34 (0.50) |

| Extent that service met your needs? | 3.00 (0.65) |

| Recommend to a friend? | 3.60 (0.51) |

| Satisfied with amount received? | 3.20 (0.77) |

| Helped you deal more effectively with problems? | 3.27 (0.46) |

| Overall, how satisfied? | 3.47 (0.52) |

| If seeking help again, would you come back to the service? | 3.53 (0.64) |

Note. Scale of 1–4 (1=worst; 4=best); Only those receiving the TMBI provided satisfaction ratings.

3.2. Longitudinal group by time outcomes across 1-month follow-up

Results from the mixed effect models suggested significant group by time interactions on several outcomes of interest (Table 3). As shown in Table 1, no significant differences were observed at baseline for any of the outcome measures.

Table 3.

Longitudinal mixed effects regression group × time outcomes across 1 month.

| Coefficient/risk ratio |

Standard error |

95% CI Lower, Upper |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness to change (Total Score) | 9.02 | 3.73 | 1.70 | 16.32 | .02 |

| Precontemplation | 3.52 | 1.69 | 0.20 | 6.84 | .04 |

| Contemplation | 1.71 | 1.05 | −0.35 | 3.38 | .10 |

| Action | 2.92 | 1.78 | −0.57 | 6.41 | .10 |

| Maintenance | 1.39 | 1.39 | −1.34 | 4.12 | .32 |

| Reasons for Living | 29.60 | 10.22 | 9.57 | 49.63 | <.01 |

| Suicidal ideation | 1.36 | 0.24 | 0.95 | 1.93 | .09 |

Note: All mixed effect regression models included gender in the analysis. Coefficients are utilized for all outcomes except for suicidal ideation, for which a risk ratio was used to report the Poisson regression model outcome. The coefficients and risk ratio reflect the group × time interaction effects for each outcome.

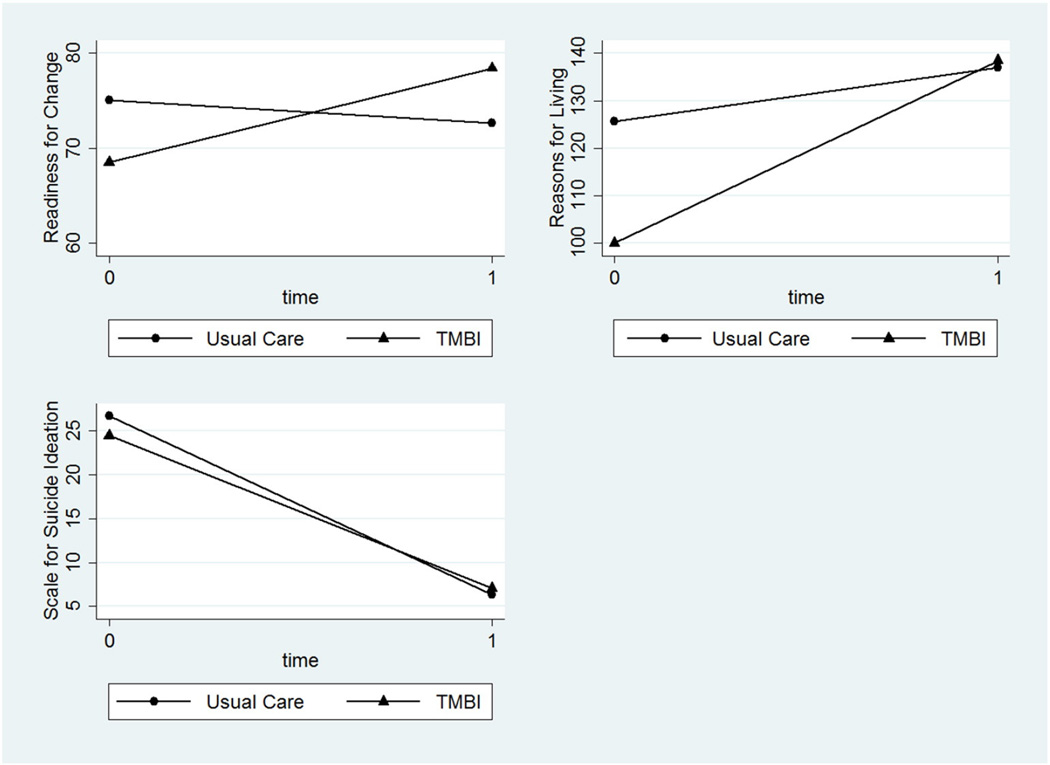

The TMBI group demonstrated significant positive improvement in motivation to address their problems compared to those in the usual care group (β=9.02, S.D.=3.73, CI=1.70, 16.32; Fig. 3). A closer examination of the subscales with the Stages of Change questionnaire revealed a noticeable trend towards greater improvements across the Precontemplation (β=3.52, S.D.=1.69, CI=0.20, 6.84), Contemplation (β=1.71, S.D.=1.05, CI=−0.35, 3.38), and Action subscales (β=2.92, S.D.=1.78, CI=−0.57, 6.41) in comparison to the usual care group, suggesting a consistent response towards addressing concerns across the transtheoretical model of behavior change. Significant improvements across time on Reasons for Living improvements were also observed for the TMBI group compared to the usual care group (β=29.60, S.D.=10.22, CI=9.57, 49.63; Fig. 3). Inspection of trajectories between baseline and 1-month assessments for each of the study patients demonstrated a wide range of baseline levels for the TMBI group, 100% of which reported improvement on the measure at 1-month compared to 54% in the usual care group. Although a trend was observed for greater improvement of suicidal ideation for the TAU group (RR=1.36, S.D.=0.24, CI=0.95, 1.93), the majority of patients (~70%) in both conditions reported no desire for suicide at the 1-month assessment.

Fig. 3.

Baseline and 1-month Stages of Change Questionnaire, Reasons for Living Inventory, and Scale for Suicide Ideation total scores. Stages of Change Questionnaire, Reasons for Living Inventory, and Scale for Suicide Ideation total scores for TMBI and usual care groups at baseline and 1-month follow-up assessments.

4. Discussion

The current study demonstrates that a brief intervention for medically admitted suicide attempt survivors could be feasibly delivered and studied in a Level 1 trauma center. Acceptability of the TMBI was evidenced by the client satisfaction ratings reported by those who received the intervention. Patients rated the brief intervention as “good” to “great” on all items related to client satisfaction. Additionally, we observed significant interaction effects across the 1-month time period, such that patients who received the TMBI demonstrated positive linear trends for readiness to change behaviors and important reasons why they would choose not to suicide.

Expanding on the study outcomes, we found a positive linear trend for three of the four subscales contained within the Stages of Change Questionnaire that represented improvements in Pre-Contemplation, Contemplation, and Action phases of working towards addressing their current concerns. Although not all of the analyses reflected statistically significant differences, the consistent trend of increasing awareness and willingness to address one’s problems was seen across most of the spectrum of readiness to change. Although the median number of suicide attempts appears to be somewhat high (Overall Median=2), the current sample seems to be representative of the larger population of patients who seek care at urban acute care hospital settings for self-directed violence. In fact, our median suicide attempt history mirrors that found by Comtois and colleagues [27] in a recent study of N=202 patients treated in an emergency department following self-directed violence. It is also not surprising that 63% of our study participants reported at least 1 previous suicide attempt, given the strong association between past and future suicide-related behaviors. Therefore, it does appear that the intervention is properly designed for the trauma patient population; however, future research is needed to determine the extent to which a teachable moment is fostered by individuals surviving a first attempt, or for lesser forms of self-directed violence, such as suicidal ideation, planning, and aborted attempts. It would not be too difficult to adjust the language of the TMBI to focus on other aspects of self-directed violence, but we have no available data to inform the acceptability of such an application.

Other researchers are examining the application of brief interventions for suicidal patients in different settings, such as Safety Planning with non-demand follow-up contacts in emergency departments [28] and Motivational Interviewing for suicidal Veterans on inpatient psychiatry units [29]. Interacting with suicide attempt survivors in their medical/ surgical hospital room is an unstudied clinical situation. The TMBI emphasis on collaboration and functional analysis is designed to enhance and seize upon the elevated readiness to change that exists in the sentinel event effect, i.e., “teachable moment,” window. Indeed, a high average baseline score for readiness to change for all participants was observed in the current study (M=72.0, S.D.=11.56; full scale range 18–90), perhaps indicating a unique window of opportunity for engagement. Those patients who received the TMBI were more likely to report even greater readiness to change scores at the 1-month assessment compared to a decrease in motivation for the usual care condition. Both the intervention and usual care groups reported significant declines in suicidal ideation from baseline to 1-month. The usual care group had a somewhat quicker, albeit non-significant, reduction in suicidal ideation across 1 month. Additionally, the same approximate percentage (70%) of patients on each condition reported no suicidal thoughts at the 1-month assessment. Therefore, the data does suggest no likely iatrogenic effects associated with the TMBI, though additional time points would provide more conclusive information.

Care for suicide attempt survivors could be expanded to include evidence-based outpatient treatments [23,26,30] and non-demand follow-up contacts [31,32]. Although a more comprehensive program would likely lead to even greater improvement in outcomes across time, it nevertheless requires services by additional personnel. The TMBI can be delivered during the course of usual care procedures by existing care providers, with only additional costs associated with clinician training and time spent with patients. Furthermore, adding additional services would dilute the ability to study the full impact of an intervention specifically timed to take advantage of the sentinel event effect following a recent suicide attempt, which is one of the key areas of innovation in the current study.

Despite the promising results from this intervention development study, several methodological issues limit our findings. First, the lead author who created the intervention was the only clinician to deliver the TMBI. Future research must demonstrate that a wide range of care providers can be trained to deliver the TMBI with acceptable levels of adherence. Second, the study involved a small sample of patients and was not intentionally conducted to measure the efficacy of the TMBI. Third our study was limited to one follow-up assessment to measure potential changes across time. Fourth, we used an adolescent version of the Reasons for Living Inventory which may have resulted in measurement error as applied to all ages in our sample. We are currently conducting a larger pilot study of the TMBI at a Level 1 trauma center wherein we are addressing these methodological limitations by training multiple interventionists representing various levels and disciplines of training and conducting follow-up interviews at 1-, 3-, and 12-months with an updated assessment battery.

Fourth, patients who were disappointed to survive the suicide attempt may have been less likely to participate in the research study. Anecdotally, the first author did recruit and intervene with at least one patient who wished that he had died. In reviewing the individual baseline assessments, there was a wide range of post-suicide attempt readiness to change, suggesting that aspects of the teachable moment model were under-stimulated and resulted in less initial movement towards rejecting suicide in some patients. It is possible that these patients did regret not dying, but future research is needed to further test this question. Fifth, patients in the usual care condition did not complete the CSQ; therefore, it is not possible to evaluate the acceptability and possible impact of usual care on the study outcomes. The setting for the study is a level 1 trauma center that serves a safety net population in King County, WA, including 10% monolingual non-English speaking individuals. It is also a primary training site for University of Washington School of Medicine, in addition to the University of Washington Medical Center. Sixth, additional symptoms could be evaluated in future studies, including depression, hopelessness, anxiety, and agitation.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the acceptability and feasibility of a brief intervention delivered to suicide attempt survivors currently hospitalized on a medical/surgical floor. Additionally, the use of readiness to change as an outcome is novel for suicide-specific brief interventions. We believe this construct, along with the reasons for living scale, match well onto the constructs represented in our conceptual model regarding elevated motivation and heightened self-concept and social role in the limited window following a suicide attempt. Future research examining contextual characteristics, such as timing and clinical setting, will further inform ways to maximize the impact of services provided to suicide attempt survivors treated in acute medical settings.

Acknowledgements

The current study was supported by grants T32HD057822 (PI: Rivara) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and K24MH086814 (PI: Zatzick) from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: none.

References

- 1.The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: 2011–2012 Annual Report. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitman A, Caine E. The role of the high-risk approach in suicide prevention. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:175–177. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasgow RE, Chambers D. Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conner KR, Langley J, Tomaszewski KJ, Conwell Y. Injury hospitaliztion and risks for subsequent self-injury and suicide: A national study from New Zealand. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1128–1131. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman DC, Soderberg R, Rivara FP. Prior injury and motor vehicle crash as risk factors for youth suicide. Epidemiology. 1993;4:115–119. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders KEA, Hawton K, Fortune S, Farrell S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical stadd regarding people who self-harm: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Kotzalidis, Tatarelli R. Emergency staff reactions to suicidal and self-harming patients. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:169–178. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200508000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zatzick D, Jurkovich G, Rivara FP, Russo J, Wagner A, Wang J, et al. A randomized stepped care intervention trial targeting posttraumatic stress disorder for surgically hospitalized injury survivors. Ann Surg. 2013;257:390–399. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826bc313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreaux ED, Bock B, O'Hea E. When an event sparks behavior change: an introduction to the sentinel event method of dynamic model building and its application to emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride C, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18:156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: evidence based on longitudinal registers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:427–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, Wagner A. Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII): development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:303–312. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linehan MM, Comtois KA. University of Washington; 1999. Suicide attempt and self injury count. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osman A, Downs WR, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, Baker MT, Baker JR, et al. The Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (RFL-A): development and psychometric properties. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54:1063–1078. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199812)54:8<1063::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McConnaughy EA, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 1983;20:368–375. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis CC, Simons AD, Silva SG, Rohde P, Small DM, Murakami JL, et al. The role of readiness to change in response to treatment of adolescent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:422–428. doi: 10.1037/a0014154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. The UCSF Client Satisfaction Scales: I. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8, in The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: US, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999. pp. 1333–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linehan MM. Demographic data survey (DDS) Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comtois KA, Jobes DA, O'Connor SS, Atkins DC, Janis K, Chessen CE, et al. Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS): feasibility trial for next-day appointment services. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:963–972. doi: 10.1002/da.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jobes DA. Managing suicidal risk. New York, NY: US, Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knox KL, Stanley B, Currier GW, Brenner L, Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Brown G. An emergency department-based brief intervention for veterans at risk for suicide (SAFE VET) Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl. 1):S33–S37. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Britton PC, Conner KR, Maisto SA. An open trial of motivational interviewing to address suicidal ideation with hospitalized veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:961–971. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:563–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comtois KA, Kerbrat AH, Atkins DC, Roy-Byrne P, Katon W. Self-reported usual care for self-directed violence during the 6 months before emergency department admission. Med Care. 2015;53:45–53. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, Wasserman D, De Leo D, Bolhari J, Botega NJ, et al. Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: a randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:703–709. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.046995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motto JA, Bostrom AG. A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:828–833. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]