Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) is poised to take a significant place in the prenatal setting given its increased yield over standard karyotyping, but concerns regarding ethical and counseling challenges remain, especially associated with the risk of uncertain and incidental findings. Guidelines recommend patients receiving prenatal screening undergo genetic counseling prior to testing, but little is known about women’s specific pre- and post-testing informational needs, as well as their preference for return of various types of results.

METHODS

The present study surveys 199 prenatal genetic counselors who have counseled patients undergoing CMA testing and 152 women who have undergone testing on the importance of understanding pre-test information, return of various types of results, and resources made available following an abnormal finding.

RESULTS

Counselors and patients agree on many aspects, although findings indicate patients consider all available information very important, while genetic counselors give more varying ratings.

CONCLUSION

Counseling sessions would benefit from information personalized to a patient’s particular needs and a shared decision-making model, so as to reduce informational overload and avoid unnecessary anxiety. Additionally, policies regarding the return of various types of results are needed.

BACKGROUND

Chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) can identify submicroscopic genomic deletions and duplications not detectable by traditional karyotyping. In pediatric settings, CMA testing is a first tier test for detection of genomic abnormalities in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, where about 20% of children are predicted to test positive for a causative pathogenic copy number variant1, frequently leading to changes in patient management.2,3 In prenatal settings, because of the increased yield of CMAs compared to standard karyotyping, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) has recommended microarray testing be offered when a fetal structural anomaly is detected on ultrasound,4 and in this situation CMA testing provides clinically relevant information not detectable on karyotyping in about 6.0% of cases.5 When CMA testing is done in lower risk situations, such as advanced maternal age, abnormal findings are seen in 1.7% of cases after a normal karyotype.5 Because of this increased yield over standard karyotyping, ACOG also recommends offering CMA testing to women carrying a structurally normal fetus who are undergoing an invasive procedure for any indication.4 In Europe, guidelines for offering prenatal microarray testing vary across countries,6 with many either recommending microarrays as a first tier test after detecting a fetal anomaly on ultrasound or when invasive testing is performed.7

Despite improved detection rate and faster turnaround time,4,8 enthusiasm for more widespread use of prenatal CMA testing has been tempered by ethical and counseling challenges.7,9,10,11,12 This includes the possibility of laboratories detecting and reporting copy number variants (CNVs) of uncertain clinical significance (VOUS), the detection of CNVs associated with conditions with variable expression or penetrance, and incidental findings including CNVs associated with increased risk for adult-onset conditions or neuropsychiatric disorders.10,11,13,14

Currently, ACOG and European guidelines recommend a woman offered prenatal genetic testing be given education and counseling to understand and weigh benefits and limitations of various testing modalities, and then make an autonomous decision most consistent with her values and preferences.15,16 ACOG specifically recommends pre-test counseling for CMA testing include discussion of the potential for results of uncertain significance, as well as the possibility of incidental finding results suggesting non-paternity, consanguinity, and susceptibility to adult-onset conditions.4

Due to the small amount of time in early prenatal visits devoted to discussion of genetic tests17 and the increasing number and complexity of testing options available, many are concerned women are making decisions after receiving only minimal information and with poor understanding.18,19 In response, various modalities to evaluate risk, provide education, and support decision-making for prenatal testing have been developed and evaluated,20,21,22 and Minkoff and Berkowitz19 have suggested all women meet with a genetic counselor early in pregnancy to review personal genetic risks and testing options.

There is limited data on women’s informational needs as they consider prenatal genetic tests,23 although when surveyed, most women express interest in learning about many aspects of testing.18,24,25 However, since a variety of conditions may be detectable with a single test, and the risk of any specific finding is very low, an appropriate balance between informing women about all possibilities and preventing information overload and unnecessary anxiety must be found.24,26,27 The discussion agenda in genetic counseling sessions is frequently set by the genetic counselor,28,29 in part because women may not discuss their informational needs.30 In practice, most genetic counseling sessions are dominated by the clinician, with dialogue focusing on biomedical or instructive, rather than psychosocial topics, diagnosable conditions, follow-up options if the test is positive, or decision-making28,29,31,32,.33 Sessions where the counselor sets the agenda may not meet the patient’s needs, as there is frequently a discrepancy between what clinicians and patients believe is most important for making an informed decision.34,35

In support of patient autonomy, the vast majority of genetic counselors and geneticists (~80%) believe woman should be given a choice about what kinds of unexpected diagnoses are returned to them.36 Despite wanting as much information as possible about their fetus or neonate,37,38,39 including CMA results of uncertain clinical significance,40 when given such results prenatally, many women express distress and prolonged uncertainty about their child’s development and seek out additional information, frequently from genetic counselors.41,42 Genetic counselors, however, may lack confidence interpreting ambiguous results, counseling patients about uncertain prenatal findings, and facilitating decision making around the possibility of terminating a pregnancy in the face of uncertain results.43,44

To further understand beliefs about what should be included in pre-test education and counseling sessions for prenatal CMA testing, as well as which types of results should be returned, we surveyed women who had prenatal CMA testing and genetic counselors who had counseled women about the test.

METHODS

Recruitment of patients having CMA testing

Patients who had prenatal CMA testing performed through one of 11 prenatal testing facilities in the United States collaborating with Columbia University on their NIH-funded project “Prenatal Microarray Follow-Up Study” learned about the study from a pamphlet provided after receiving results. The pamphlet invited patients who had received testing results in the past 4–6 weeks to participate in a short online survey. Recruitment occurred between June 2013 and July 2014.

Recruitment of genetic counselors

Participants were members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) who were recruited either through postings on NSGC on-line discussion forums or through personalized emails. Eligible counselors had discussed prenatal CMA testing with at least one pregnant woman within the past year. We first posted an announcement of the survey and survey link on the NSGC Prenatal Counseling Special Interest Group (SIG) discussion forum. A week later, we posted an announcement of the survey on the NSGC main discussion forum, and then re-posted the announcement a week later. One week following, personal email and survey link were sent to 125 randomly selected genetic counselors who listed their specialty as prenatal counseling, making sure to exclude email addresses to which an incentive had already been paid for completing a survey (see below). Surveys were completed between February and April of 2013.

Survey instrument and data collection

Two separate survey instruments, one for patients who had CMA testing and one for genetic counselors, were developed by the study team. Each included a series of items to assess opinions about 1) the importance of patients understanding various types of information that could be included in pre-test counseling; 2) which types of incidental findings or results relating to susceptibility to various types of conditions should be returned to patients tested; and 3) resources needed for those patients receiving positive results. Items asked about the importance of each on a scale of 1 = “Not at all important” to 4 = “Very important.”

The patient survey included items to gather data on their reason for CMA testing, type of procedure performed, education, race, ethnicity, age, and religious affiliation. The genetic counselor survey included items relating to the counselor’s years of experience, number of patients counseled about CMA testing, gender, age, religious affiliation, race, and ethnicity.

An informed consent statement was included at the beginning of the survey, and respondents could only complete the survey after checking a box indicating informed consent to participate. At the end of the survey, respondents were taken to a second, unlinked survey asking them to provide their email address for a $10 e-gift card, ensuring survey responses were anonymous.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented for both patients undergoing CMA testing and genetic counselors. Due to the highly skewed nature of responses, comparisons between groups were performed using non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U), although means are presented to aid in interpretation. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

Respondents

One hundred and fifty-five patients completed the survey, with 152 answering all questions (Table 1). They were generally well educated (86% were college graduates), white (77.5%) and non-Hispanic (89%). The primary reason for testing was age, and 36 patients (26%) reported abnormal or VOUS CMA test results.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (N = 155)

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| < College graduate | 21 | 14 |

| College graduate | 53 | 34 |

| Post-graduate | 81 | 52 |

| Race | ||

| White | 120 | 77.5 |

| Asian | 16 | 10 |

| Black/ African American | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 10 | 6.5 |

| More than one | 7 | 5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 17 | 11 |

| Non-Hispanic | 138 | 89 |

| Religious Affiliation | ||

| Catholic | 41 | 26 |

| Jewish | 21 | 33 |

| Protestant | 12 | 8 |

| None | 54 | 35 |

| Other | 15 | 10 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single, never married | 11 | 7 |

| Married/ partnered | 141 | 91 |

| Separated or divorced | 3 | 2 |

| Living biological children | ||

| Yes | 71 | 46 |

| No | 83 | 54 |

| Indication for testing* | ||

| Maternal age | 78 | |

| Abnormal integrated or serum screen | 17 | |

| Ultrasound anomaly | 48 | |

| Positive family history | 11 | |

| Previous child with genetic abnormality | 16 | |

| Mother and/ or father carry a chromosome deletion or duplication | 10 | |

| Other | 10 | |

| No response | 3 | |

| Procedure performed* | ||

| Amniocentesis | 79 | |

| CVS | 80 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| Result | ||

| Normal | 116 | 76 |

| Abnormal | 16 | 11 |

| Variant of uncertain significance | 20 | 13 |

Could select more than one indication

Of the 199 genetic counselors who responded to the survey, 188 of them completed it by answering all questions (Table 2). One hundred and nineteen counselors responded to the posting on the discussion forums, and 74 (59.2% response rate) completed the survey after receiving the email invitation. They were primarily female (89%), white (85%) and non-Hispanic (98%). On average, they had been practicing for 9 years (range=1–35). Most (64%) reported devoting more than 75% of their professional time to counseling prenatal patients.

Table 2.

Genetic Counselor Demographics (N = 199)

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 59 | 30 |

| 30–39 | 82 | 41 |

| 40–49 | 27 | 13.5 |

| 50 or older | 17 | 8.5 |

| No response | 14 | 7 |

| Race | ||

| White | 169 | 85 |

| Black/ African American | 3 | 1.5 |

| Asian | 9 | 4.5 |

| Other | 2 | 1 |

| More than one race | 3 | 1.5 |

| No response | 13 | 6.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 3 | 1.5 |

| Non-Hispanic | 179 | 90 |

| No response | 17 | 8.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 178 | 89 |

| Male | 8 | 4 |

| No response | 13 | 7 |

| Religious Affiliation | ||

| Catholic | 43 | 21.5 |

| Protestant | 54 | 27 |

| Jewish | 19 | 10 |

| Muslim | 1 | 0.5 |

| None | 42 | 21 |

| Other | 18 | 9 |

| No response | 22 | 11 |

| Years in Practice | ||

| <5 | 76 | 38 |

| 5–10 | 57 | 29 |

| 11–20 | 46 | 23 |

| >20 | 20 | 10 |

| Approximate number of patients discussed prenatal microarray testing with | ||

| 0–10 | 61 | 31 |

| 11–50 | 84 | 42 |

| >50 | 54 | 27 |

| Number of patients opting for prenatal microarray testing | ||

| 0–10 | 111 | 56 |

| 11–50 | 70 | 35 |

| >50 | 14 | 7 |

| No response | 4 | 2 |

Survey responses

Importance of understanding information in pre-test counseling

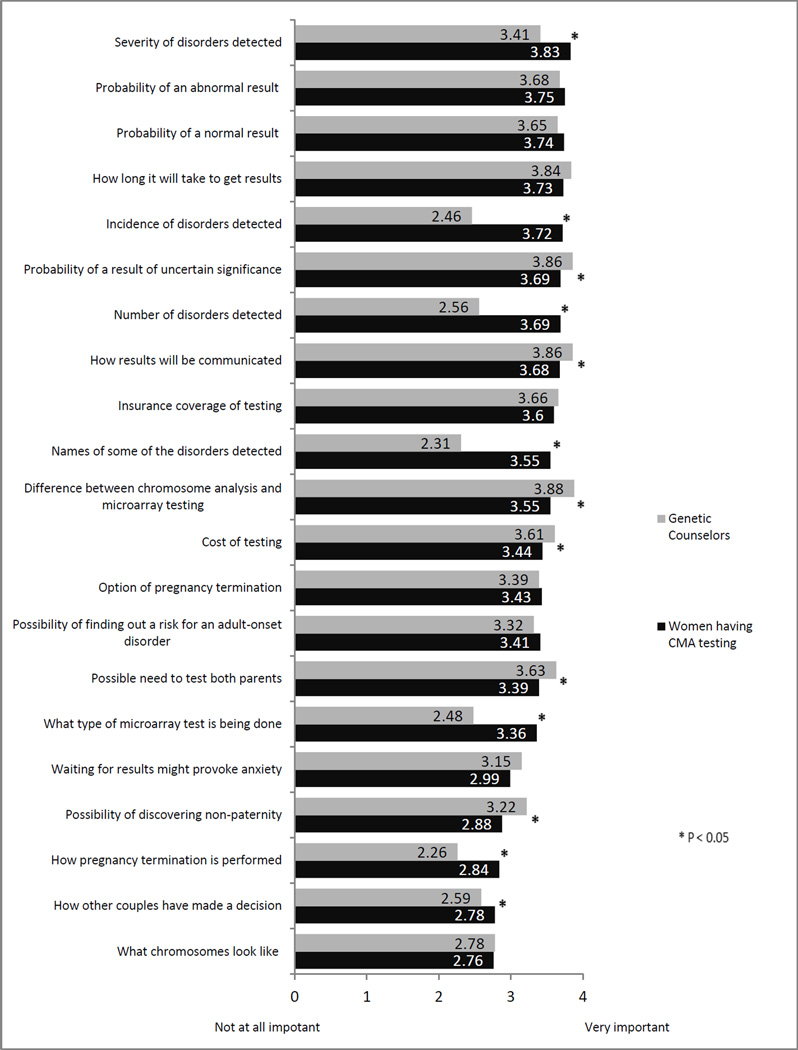

The mean importance of understanding various types of information that could be included in pre-test genetic counseling by type of respondent (genetic counselor or patient having prenatal CMA testing) is included in Figure 1. Both genetic counselors and patients agree it is important patients understand all types of information included in the survey. Patients considered information related to the type of testing being done, pregnancy termination, other couples’ decision making process, and the severity, number and incidence of diseases detected significantly more important to understand than genetic counselors did (all p<.05). Genetic counselors considered information about the communication of results, the cost of testing, the possibility of results of uncertain significance, and differences between chromosome analysis and microarray testing to be significantly more important to understand than did patients (all p <.05).

Figure 1.

Importance of Understanding Information Included in Pre-test Counseling

The informational items most likely to be endorsed as “Very important” to understand among patients included the name of some disorders detected (86%), probability of a normal result (80%) and the probability of an abnormal result (80%). Patients assigned lowest importance to understanding what chromosomes look like (mean=2.76) and how other couples made their decisions (mean=2.78). The items counselors considered to be “Very important” for patients to understand were differences between microarray and chromosome analysis (85%), the probability of results of uncertain significance (82%), and insurance coverage of testing (68%). Genetic counselors assigned least importance to information about how pregnancy termination is performed (mean=2.26). Among patients, there were no significant differences in ratings of importance according to whether the test result was normal or abnormal/uncertain (all p > 0.05).

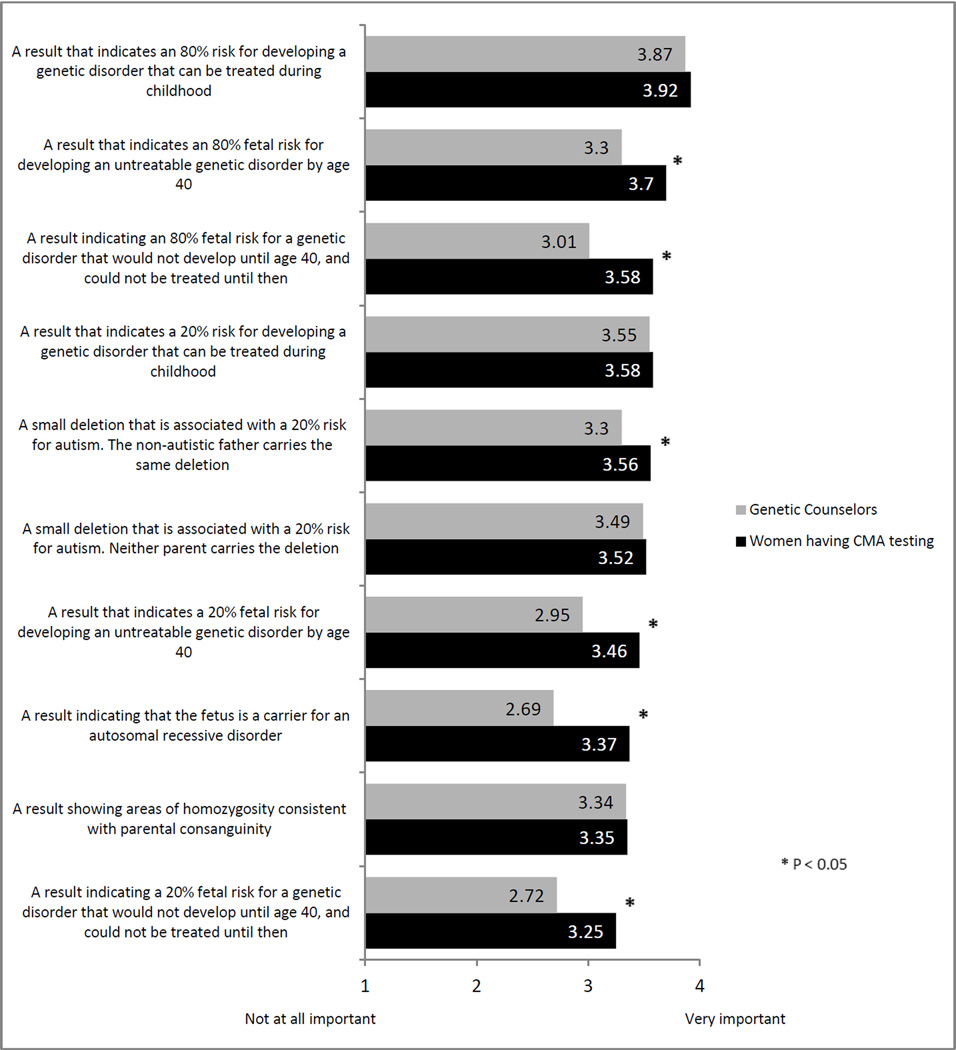

Importance of reporting incidental findings or results relating to disease susceptibility

Overall, both genetic counselors and patients believe it is important to report all types of possible results (Figure 2). Patients and counselors did not differ significantly with respect to reporting of results indicating a 20% risk for developing a treatable childhood genetic disorder or a 20% risk for autism in which neither parent carries the same genetic change. For all other results, patients rated the importance of reporting results as higher than did counselors (p < .05). Among patients, there were no significant differences in their rating of the importance as a function of whether the test result was normal or abnormal/uncertain (all p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Importance of Reporting Various Types of Results

The result rated most important to return by both patients (91%) and counselors (82%) would be a result indicating an 80% risk for developing a treatable childhood-onset genetic disorder. Patients rated a result indicating a 20% fetal risk for a genetic disorder that would not develop until age 40 and could not be treated until then as least important (mean=3.25). Genetic counselors assigned the least importance to a result indicating that the fetus is a carrier for an autosomal recessive disorder (mean=2.69).

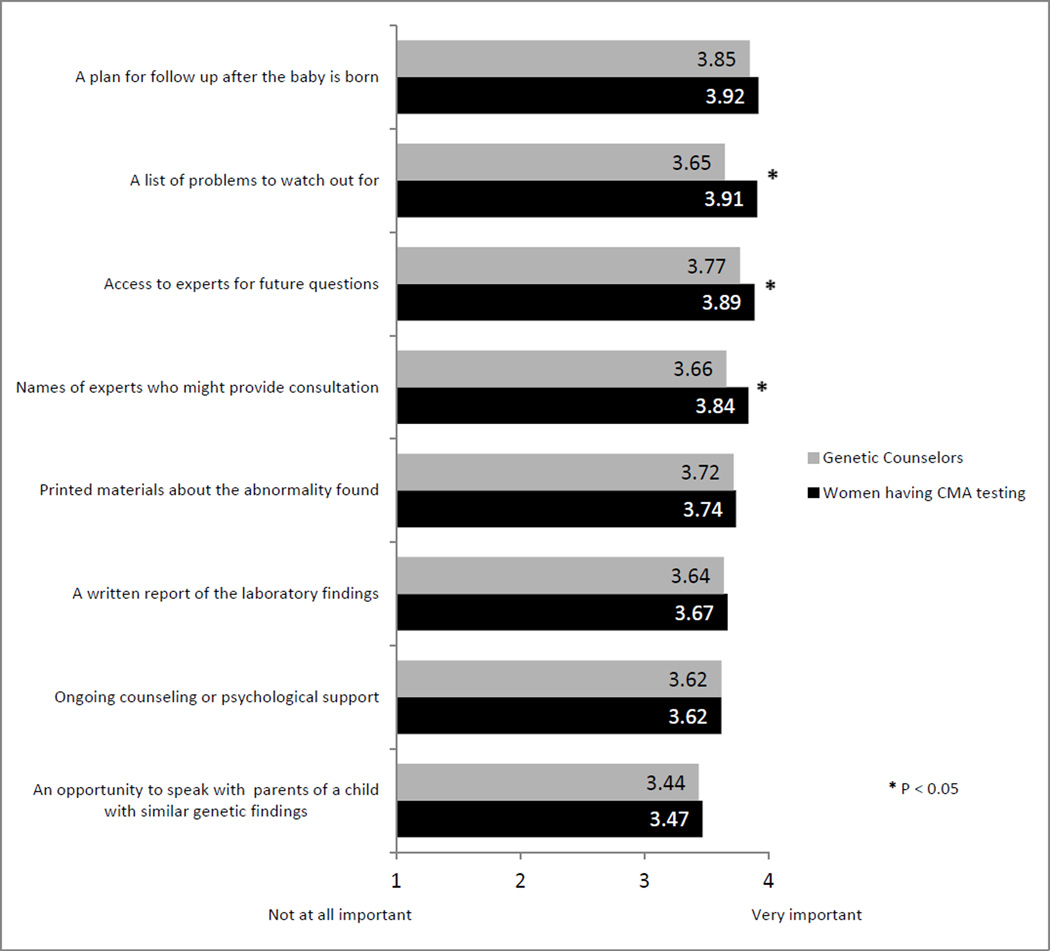

Importance of the availability of resources for patients receiving positive results

Both counselors and patients agreed it is important to make all resources listed on the survey available to patients receiving abnormal or uncertain prenatal microarray results (Figure 3). Patients having CMA testing reported a list of problems to watch out for and the name of and access to experts for future questions to be significantly more important than genetic counselors did (all p <.05). Ratings of importance did not differ as a function of whether test results were normal or abnormal/uncertain (all p > 0.05). Both patients and genetic counselors assigned the greatest importance to a plan for follow up after the baby is born (mean=3.92; mean=3.85, respectively), and least importance, although marginally, to an opportunity to speak with parents of a child with similar genetic findings (mean=3.47; mean=3.44, respectively).

Figure 3.

Importance of Resources for Patients Receiving Abnormal or Uncertain Results

DISCUSSION

We found genetic counselors and patients having prenatal CMA testing agree on the importance of many elements relating to pre- and post-test counseling. As previously reported, patients want to understand all information relating to prenatal testing, and want as much information about the future health of their unborn child as possible.39,45 In comparison, genetic counselors consider some information to be of lower importance, likely reflecting their desire to prioritize information discussed in counseling sessions. Additionally, they were somewhat more selective in the importance of returning various types of results found on prenatal CMA testing.

Despite many similarities between the beliefs of genetic counselors and patients, several significant differences emerged, providing insight into the structure genetic counseling sessions might take. As previous evidence has suggested,28 genetic counselors rated procedural information, such as communication of results, cost of testing, possibility of results of uncertain significance, and differences between chromosome analysis and microarray testing, as being significantly more important than did patients. Patients reported information about the severity, number, and incidence of diseases detected, how pregnancy termination is performed and other couples’ decision making process as significantly more important than genetic counselors did. Somewhat surprisingly, patients rated information about other couples’ decision process among the lowest. This may suggest patients view their choices regarding testing as very personal and, as has been shown previously, value more personalized information as they make prenatal testing decisions.46 Most important to patients was information about the severity of detectable disorders and probability of an abnormal/ normal result, indicating patients most want to know the chance of the test revealing their baby has a serious problem.

These findings and previous research suggest counselors should identify issues that are most important for the individual patient at the outset of the counseling session and then personalize counseling to address those issues.29,37 Although most patients want to understand a wide variety of items relating to prenatal testing, studies have shown that when genetic counseling sessions are information dense, or when patients are under emotional stress, understanding may be poor.29,42 Importantly, assistance with decision-making is frequently lacking in genetic counseling sessions.33 Adopting a shared decision-making model, in which the patient identifies information most useful to her would alleviate the problem of information overload and allow patients to reach a decision more grounded in her goals and values.47 Patients are primarily interested in information relevant to their own particular pregnancy circumstance and outcome as opposed to generalizable information often emphasized in counseling sessions.29 However, an effective method for delivering personalized information in this rapidly evolving field has not yet been established.48 One useful method of identifying patients’ informational needs is through a pre-counseling survey asking patients to identify personally important questions for discussion.30 This has been effectively implemented in other settings, such as cancer risk counseling, and is associated with an overall more positive counseling experience.49,50 Consistent with a shared-decision model, questions may also elicit patient’s values relating to pregnancy and parenting so counselors can engage with them in a discussion around these values to reach an informed and comfortable decision together.29 Such discussions may be especially important as beliefs and values about prenatal genetic testing, detectable conditions, and pregnancy termination vary both across and within cultures51,52,53 and, some important topics, such as raising a child with a disability, frequently remain undiscussed.31 Additional information about risks, procedures, and possible results could be provided through supplemental print or on-line information, either before or after the genetic counseling session, thus allowing time to be spent on personalized education and decision-making.

In the reporting of incidental findings and results relating to disease susceptibility, patients assigned high importance to learning all possible results. Both patients and genetic counselors ascribed greatest importance to results indicating a high likelihood of a genetic disorder that could be treated in childhood. Although not as important as other types of results, nearly all patients agreed they would like to learn about incidental findings indicating susceptibility to adult onset illnesses, even if untreatable, and carrier status. Genetic counselors were more selective in which types of results are important to return to patients, indicating not all results were of equal value in their mind. Responses may demonstrate genetic counselors’ reluctance to share findings considered uncertain or irrelevant to post-testing decision making, such as results indicating a low probability of developing a disease in adulthood.

Policies regarding return of incidental findings from prenatal testing are needed in light of the importance pregnant patients place on learning about their baby’s susceptibility to a variety of conditions. If patients are given a choice about return of incidental findings, counseling should focus on both the risks and benefits of learning about results related to adult-onset conditions, especially if results indicate a low or uncertain probability of any clinical issues. If patients are not given a choice about return of incidental findings, they should be made aware of the small but real chance such a result could be found, and given the option to decline testing if they would not wish to learn such results.

If a woman has a positive test result, both patients and genetic counselors agree it is important to make a variety of resources available. Not surprisingly, both patients and genetic counselors assigned greatest importance to a plan for follow up after the baby is born, as this will help guide appropriate treatment and structure expectations post-delivery. Given the especially high importance assigned to both emotionally supportive and informational resources, counselors should be prepared to offer or refer patients to a range of resources targeting their needs, which may include third party experts in the field, as well as psychological support.

Although many experts predicted prenatal CMA testing was poised to possibly replace standard karyotyping, the recent introduction of non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPS) for aneuploidies through the analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal circulation has led to a dramatic decrease in the number of invasive prenatal tests being performed.54,55 Some companies have added testing for a group of well-defined microdeletion syndromes to NIPS tests for aneuploidies,56,57 and in the future, it is likely testing for additional conditions associated with CNVs will be offered.58,59 Adding to the future prenatal testing landscape, fetal whole genome sequencing is technically feasible,60 and according to some experts, inevitable.61 With such testing, many of the same challenges associated with CMA testing outlined above will only be amplified.

The present study is among the few to explore women’s informational and resource needs associated with prenatal CMA testing and one of the only studies to assess attitudes towards return of results among patients who have personal experience with prenatal genomic testing. However, the present research has some limitations. The patients surveyed were demographically homogenous, being mostly white, highly educated, and all from the United States. It is important to consider how responses from other racial, socioeconomic, and cultural groups may differ from those presently surveyed. Additionally, male partners were not surveyed. Future research may also look at ways of aiding genetic counselors with setting a counseling agenda that best meets the needs of a particular patient. Measures of patient understanding, decision satisfaction, and wellbeing associated with various counseling formats should be assessed as well.

CONCLUSIONS

Genetic counselors and patients receiving CMA testing agree on the importance of many aspects of pre- and post- test counseling, including pre-test information, reporting of results, and needed resources after positive results. Despite many similar ratings of importance, patients assigned a particularly high level of importance to all information, results and resources. Given these findings, we recommend: 1) genetic counselors aid patients in identifying and prioritizing the pre-test information that is most important to them; 2) given the importance most patients place on learning a range of possible uncertain and incidental findings results, policies for return of results are needed that take into account patient perspectives; 3) genetic counselors should offer both informational and emotionally supportive resources to patients who have received positive results; and 4) educational materials are needed that provide details about all aspects of prenatal CMA testing to supplement pre-test genetic counseling.

What’s already known about this topic?

Most women desire comprehensive education about prenatal screening and testing for genetic disorders, but little is known about their specific needs pre- and post-testing. In order to develop guidelines for return of uncertain and incidental findings from prenatal genomic testing, data are needed on women’s preferences for return of various types of results.

What does this study add?

This study adds to the limited knowledge of women’s informational and resource needs associated with prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) testing and is one of the only studies to assess attitudes towards return of results among patients who have personal experience with prenatal genomic testing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Amita Russell, MS, CGC and Jessica Feinberg for their assistance with subject recruitment, and to W. Andrew Faucett, MS, CGC and Heather Shappell, MS, CGC for their assistance with the development of the survey instruments as well as with subject recruitment. Funding for this study was secured by Ronald Wapner, MD, and we are grateful for the guidance he has provided throughout this study.

Funding source: This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Development, National Institutes of Health (UO1-HD-055651). There was no additional involvement from funding sources.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(5):749–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayeems RZ, Hoang N, Chenier S, et al. Capturing the clinical utility of genomic testing: medical recommendations following pediatric microarray. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson LB, Applegate CD, Wohler E, et al. The impact of chromosomal microarray on clinical management: a retrospective analysis. Genet Med. 2014;16(9):657–664. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion No. 581: the use of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1374–1377. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000438962.16108.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2175–2184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vetro A, Bouman K, Hastings R, et al. The introduction of arrays in prenatal diagnosis: a special challenge. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(6):923–929. doi: 10.1002/humu.22050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong A, Dondorp WJ, Macville MV, et al. Microarrays as a diagnostic tool in prenatal screening strategies: ethical reflection. Hum Genet. 2014;133(2):163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crolla JA, Wapner RJ,Van Lith JM. Controversies in prenatal diagnosis 3: should everyone undergoing invasive testing have a microarray? Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(1):18–22. doi: 10.1002/pd.4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady PD, Delle Chiaie B, Christenhusz G, et al. A prospective study of the clinical utility of prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities and an exploration of a framework for reporting unclassified variants and risk factors. Genet Med. 2014;16(6):469–476. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westerfield L, Darilek S, van den Veyer IB. Counseling challenges with variants of uncertain significance and incidental findings in prenatal genetic screening and diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2014;3:1018–1032. doi: 10.3390/jcm3031018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Opstal D, de Vries F, Govaerts L, et al. Benefits and burdens of using a SNP array in pregnancies at increased risk for the common aneuploidies. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(3):319–326. doi: 10.1002/humu.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dondorp W, Sikkema-Raddatz B, de Die-Smulders C, de Wert G. Arrays in postnatal and prenatal diagnosis: an exploration of the ethics of consent. Hum Muta. 2012;33(6):916–922. doi: 10.1002/humu.22068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGillivray G, Rosenfeld JA, Gardner RJ, Gillam LH. Genetic counseling and ethical issues with chromosome microarray analysis in prenatal testing. Prenat Diag. 2012;32(4):389–395. doi: 10.1002/pd.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson KL, Czerwinski JL, Hoskovec JM, et al. NSGC practice guideline: prenatal screening and diagnostic testing options for chromosome aneuploidy. J Gen Counsel. 2013;22(1):4–15. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skirton H, Goldsmith L, Jackson L, et al. Offering prenatal diagnostic tests: European guidelines for clinical practice. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(5):580–586. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 88, December 2007. Invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1459–1467. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291570.63450.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernhardt BA, Geller G, Doksum T, et al. Prenatal genetic testing: consent of discussions between obstetric providers and pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(5 Pt 1):648–655. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell RM, Agatisa PK, Nutter B. What patients want: lead considerations for current and future applications of noninvasive prenatal testing in prenatal care. Birth. 2014;41(3):276–282. doi: 10.1111/birt.12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkoff H, Berkowitz R. The case for universal prenatal genetic counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1335–1338. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuppermann M, Pena S, Bishop JT, et al. Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1210–1217. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edelman EA, Lin BK, Doksum T, et al. Evaluation of a novel electronic genetic screening and clinical decision support tool in prenatal clinical settings. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(5):1233–1245. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1358-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanakker O, Vilain C, Janssens K, et al. Implementation of genomic arrays in prenatal diagnosis: The Belgian approach to meet the challenges. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57(4):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srebniak MI, Opstal D, Joosten M, et al. Whole genome array as a first-line cytogenetic test in prenatal diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/uog.14745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell RM, Nutter B, Agatisa PK. Patient-centered prenatal counseling: Aligning obstetric healthcare professionals with needs of pregnant women. Women Health. 2015;55(3):280–296. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.996724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin L, Van Dulmen S, Spelten E, et al. Prenatal counseling for congenital anomaly tests: parental preferences and perceptions of midwife performance. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(4):341–353. doi: 10.1002/pd.4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oepkes D, Yaron Y, Kozlowski P, et al. Counseling for non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): what pregnant patients may want to know. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(1):1–5. doi: 10.1002/uog.13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faas BH, Feenstra I, Eggink AJ, et al. Non-targeted whole genome 250K SNP array analysis as replacement for karyotyping in fetuses with structural ultrasound anomalies: evaluation of a one-year experience. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(4):362–370. doi: 10.1002/pd.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgson JM, Gillam LH, Sahhar MA, Metcalfe SA. “Testing times, challenging choices”: an Australian study of prenatal genetic counseling. J Genet Counsel. 2010;19(1):22–37. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt LM, de Voogd KB, Castañeda The routine and the traumatic in prenatal genetic diagnosis: does clinical information inform patient decision making? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(3):302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roshanai AH, Lampic C, Ingvoldstad C, et al. What information do cancer genetic counselees prioritize? J Genet Couns. 2012;21(4):510–526. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrelly E, Cho MK, Erby L, et al. Genetic counseling for prenatal testing: where is the discussion about disability? J Genet Counsel. 2012;21(6):814–824. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9484-z. (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul J, Metcalfe S, Stirling L, et al. Analyzing communication in genetic consultations—a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(1):15–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin L, Gitsels-van der Wal JT, Pereboom MT, et al. Midwives’ perceptions of communication during videotaped counseling for prenatal anomaly test: how do they relate to clients’ perception and independent observations? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(5):588–597. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrell RM, Dolgin N, Flocke SA, et al. Risk and uncertainty: shifting decision making for aneuploidy screening to the first trimester of pregnancy. Genet Med. 2011;13(5):429–436. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182076633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin L, Hutton EK, Spelten ER, et al. Midwives' views on appropriate antenatal counselling for congenital anomaly tests: do they match clients' preferences? Midwifery. 2014;30(6):600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohn Z, Adam S, Birch P, et al. Genetics professionals' perspectives on reporting incidental findings from clinical genome-wide sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(3):542–549. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norton ME, Nakagawa S, Kuppermann M. Women’s attitudes regarding prenatal testing for a range of congenital disorders of varying severity. J Clin Med. 2014;3(1):144–152. doi: 10.3390/jcm3010144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldenberg AJ, Dodson DS, Davis MM, Tarini BA. Parents' interest in whole-genome sequencing of newborns. Genet Med. 2014;16(1):78–84. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Steen SL, Diderich KEM, Riedijk SR, et al. Pregnant couples at increased risk for common aneuploidies choose maximal information from invasive genetic testing. Clin Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1111/cge.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turbitt E, Halliday JL, Amor DJ, Metcalfe SA. Preferences for results from genomic microarrays: comparing parents and health care providers. Clin Genet. 2014;87(1):21–29. doi: 10.1111/cge.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernhardt BA, Soucier D, Hanson K, et al. Women’s experiences receiving abnormal prenatal chromosomal microarray testing results. Genet Med. 2013;15(2):139–145. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hillman SC, Skelton J, Quinlan-Jones E, et al. “If it helps…” the use of microarray technology in prenatal testing: Patient and partners reflections. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(7):1619–1627. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikhaelian M, Veach PM, MacFarlane I, et al. Prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis: a survey of prenatal genetic counselors' experiences and attitudes. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(4):371–377. doi: 10.1002/pd.4071. (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernhardt BA, Kellom K, Barbarese A, et al. An exploration of genetic counselors’ needs and experiences with prenatal chromosomal microarray testing. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(6):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9702-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willis AM, Smith SK, Meiser B, et al. How do prospective parents prefer to receive information about prenatal screening and diagnostic testing? Prenat Diagn. 2014;35(1):100–102. doi: 10.1002/pd.4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durand MA, Stiel M, Boivin J, Elwyn G. Information and decision support needs of parents considering amniocentesis: interviews with pregnant patients and health professionals. Health Expect. 2010;13(2):125–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White MT. Respect for autonomy in genetic counseling: an analysis and a proposal. J Gen Counsel. 1997;6(3):297–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1025628322278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dolan SM. Personalized genomic medicine and prenatal genetic testing. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1203–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albada A, van Dulmen S, Ausems MG, Bensing JM. A pre-visit website with question prompt sheet for counselees facilitates communication in the first consultation for breast cancer genetic counseling: Finding from a randomized controlled trial. Genet Med. 2012;14(5):535–542. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albada A, van Dulmen S, Ausems MG, Bensing JM. Follow-up effects of a tailored pre-counseling website with question prompt in breast cancer genetic counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alsulaiman A, Hewison J, Abu-Amero KK, et al. Attitudes to prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy for 30 conditions among women in Saudi Arabia and the UK. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(11):1109–1113. doi: 10.1002/pd.3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nahar R, Puri RD, Saxena R, Verma IC. Do parental perceptions and motivations towards genetic testing and prenatal diagnosis for deafness vary in different cultures? Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(1):76–81. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simsek-Kiper PO, Utine GE, Volkan-Salanci, et al. Parental factors in prenatal decision making and the impact of prenatal genetic counseling: a study on Turkish families. Genet Couns. 2014;25(1):53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larion S, Warsof SL, Romary L, et al. Uptake of noninvasive prenatal testing at a large academic referral center. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):651. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiller GE, Kershberg HB, Goff J, et al. Women’s views and the impact of noninvasive prenatal testing on procedures in a managed care setting. Prenat Diagn. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pd.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hardisty EE, Vora NL. Advances in genetic prenatal diagnosis and screening. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(6):634–638. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han SC, Platt LD. Noninvasive prenatal testing: need for informed enthusiasm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):557–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wapner RJ, Babiarz JE, Levy B, et al. Expanding the scope of noninvasive prenatal testing: detection of fetal microdeletion syndromes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):332.e1–332.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peters BA, Kermani BG, Alferov O, et al. Detection and phasing of single base de novo mutations in biopsies from human in vitro fertilized embryos by advanced whole-genome sequencing. Genome Res. 2015;25(3):426–434. doi: 10.1101/gr.181255.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitzman JO, Snyder MW, Ventura M, et al. Noninvasive whole-genome sequencing of human fetus. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(137):137ra76. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hillman SC, Willams D, Carss KJ, et al. Prenatal exome sequencing for fetuses with structural abnormalities: the next step. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45(1):4–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.14653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]