Abstract

Objective

Despite the importance of TMJ disc in normal function and disease, studying the responses of its cells has been complicated by the lack of adequate characterization of the cell subtypes. The purpose of our investigation was to immortalize, clone, characterize and determine the multi-lineage potential of mouse TMJ disc cells.

Design

Cells from 12-week-old female mice were cultured and immortalized by stable transfection with human telomerase reverse transcriptase. The immortalized cell clones were phenotyped for fibroblast- or chondrocyte-like characteristics and ability to undergo adipocytic, osteoblastic and chondrocytic differentiation.

Results

Of 36 isolated clones, four demonstrated successful immortalization and maintenance of stable protein expression for up to 50 passages. Two clones each were initially characterized as fibroblast-like and chondrocyte-like on the basis of cell morphology and growth rate. Further the chondrocyte-like clones had higher mRNA expression levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (>3.5-fold), collagen × (>11-fold), collagen II expression (2-fold) and collagen II:I ratio than the fibroblast-like clones. In contrast, the fibroblast-like clones had higher mRNA expression level of vimentin (>1.5-fold), and fibroblastic specific protein 1 (>2.5-fold) than he chondrocyte-like clones. Both cell types retained multi-lineage potential as demonstrated by their capacity to undergo robust adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation.

Conclusions

These studies are the first to immortalize TMJ disc cells and characterize chondrocyte-like and fibroblast-like clones with retained multi-differentiation potential that would be a valuable resource in studies to dissect the behavior of specific cell types in health and disease and for tissue engineering.

Keywords: TMJ disc, fibrocartilage cells, immortalization, fibroblast-like cell clones, chondrocyte-like cell clones, multi-lineage potential

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJD) are a term encompassing a spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms, which involve the masticatory musculature, the TMJ and associated structures. These disorders often present with limitation or deviation in mandibular motion, open or closed locking of the jaw, TMJ sounds including clicking, popping and crepitus, and pain in masticatory muscles, TMJ and the face as well as headaches1,2. TMJD symptoms occur in approximately 6 to 12% of the adult population in the United States3. Of the patients with TMJDs, approximately 80% present with signs and symptoms of joint disease including disc displacement, arthralgia, osteoarthrosis and osteoarthritis4,5, indicating that an understanding of the underlying pathobiology of diseases of the joint, and more specifically of the contribution of the TMJ disc, could be beneficial towards potential targeted therapies for a large proportion of patients with TMJDs.

The TMJ disc is a tissue of substantial importance because of its role in normal joint function in permitting mandibular movements and because its degeneration leads to compromised joint function6-9. In humans, the TMJ and disc starts to form during the first trimester as a mesenchymal condensate in the TMJ region10,11. The disc undergoes progressive pre- and post-natal differentiation as it matures from a ligamentous / myotendinous structure to a specialized fibrocartilaginous tissue in response to function12-16. The TMJ disc transmits and dissipates loads acting on the joint and adapts its shape to changing geometry of the articular surfaces, thus minimizing small contact areas and local peak forces9,17. Because the disc is subjected to tensile, compressive and shear forces, it is configured for anisotropic mechanical behavior and has a matrix composition and organization designed to withstand these complex mechanical challenges18-22. These complex functional demands result in a heterogenous tissue with differences in the regional distribution of extracellular matrices and cell phenotypes. Thus the mature disc has a fibrous tendinous structure with fibroblastic cells at sites of tension, a primarily cartilaginous matrix and chondrocyte-like cells at sites of compression and a mixed tissue composition and intermediate fibrochondrocytic cells where the tissue is subjected to complex tensile, compressive and shear forces12,20,23-27. Ultimately, this structural organization and composition of the disc is determined by the cells contained within the tissue.

Despite the importance of TMJ disc cells to the disc's integrity, contributions to normal joint function and role in disease progression, studying their responses to physiologic, pathologic biological and mechanical cues has been complicated by the lack of a detailed characterization of the cell subtypes comprising the disc. Furthermore, even though the disc is known to contain diverse cell phenotypes, the fundamental differences between fibroblast-like or chondrocyte-like cells or other putative cell types have not been elucidated. The longer-term aim of our studies is to elucidate the key characteristics of TMJ disc cell subtypes and their specific responses to exogenous and endogenous stimuli. The specific goals of the present study were to immortalize, clone and characterize mouse TMJ disc cells that primarily demonstrate either fibroblast-like or chondrocyte-like phenotypes and determine whether these clones retain the capacity for multi-lineage differentiation. We chose to establish immortalized cell clones from mice TMJ discs both to develop a needed resource to undertake in vitro mechanistic studies, and to establish protocols for subsequently immortalizing the less readily available human cells. The immortalization, cloning and characterization of these cells provides a valuable resource for future studies to determine cell type-specific responses to physiologic or pathologic cues that could offer critical insights on disease progression, prevention and treatments including tissue engineering of the TMJ disc.

Materials & Methods

Reagents and Animals

All cell culture reagents and media were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA) and chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise mentioned. Total RNA extraction kit was from Qiagen Corp. (Valencia, CA) and quantitative real time reverse-transcriptional polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) kits were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). BCA protein assay kit was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). Transfection agent Fugene HD, hygromycin B, α-MEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), fungizone and antibiotics were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Primary antibodies to mouse vimentin, Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein (COMP), and Collagen X were from Abcam Plc. (Cambridge, MA), to mouse fibroblast specific protein 1 (FSP1), aggrecan and β-actin were from Sigma-Aldrich Corp., and to mouse collagen I and collagen II were from EMD Chemicals Inc. (Gibstown, NJ). The pGRN145 plasmid containing a cDNA encoding human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with federal and institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Determination of In Vivo Disc Cell Phenotypic Proportions and Distribution

For histological analyses, mice heads or knees were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified with 10% of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, embedded in paraffin, 5μm thick sections cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cell numbers by phenotypes and distribution were quantified from tissue sections from three mice. Cells demonstrating elongated, narrow spindle shaped appearance were morphologically classifed as fibroblast-like, while those displaying a rounded morphology with lacunae were classified as chondrocyte-like.

Isolation and Immortalization Mouse TMJ Disc Cells

TMJ discs from 12-week-old female mice were retrieved following euthanasia and cultured as described previously28,29. The discs were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing antibiotics and fungizone, minced and incubated with α-MEM containing 10% FBS, and 100 units/ml of streptomycin and penicillin for 2 to 4 weeks. Passage two cells were immortalized by stable transfection with the vector pGNR145 expressing hTERT cDNA using Fugene HD. The transfected cells were selected in presence of hygromycin B (35μg/ml) over 5 weeks and positive clones were subcultured in medium with hygromycin B (10μg/ml).

Determination of Cell Immortalization

Of 36 isolated clones, four demonstrated successful immortalization as determined by telomerase assays and the ability to maintain expression of select markers for up to 50 passages. Telomerase activity was assessed using a telomerase repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The TRAP assay involves a two-step process in which the telomerase-mediated elongation products are first amplified by PCR using GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Applied Biosystems). Samples with enzyme-inactivation by heat treatment of the cell extract for 10 minutes at 85°C prior to the TRAP reaction served as negative controls. The amplified products were quantitated by readings at an absorbance wavelength of A450nm against a blank with a reference wavelength of A690nm. The amplified ladder was visualized following electrophoresis on a 12.5% Polyacrylamide gel and staining with ethidium bromide. The stability of protein expression for versican and aggrecan previously shown to be expressed in the TMJ disc15,30 was determined by Western blots.

Cell Characterization by Morphology, Growth Rate and Specific Markers

Morphological characteristics of the cells were assessed at days 1 and 8 of culture by phase contrast microscope (Nikon TS100). For cell growth assays, the clones were seeded at a density of 1.5×104 cells in 100 mm culture dish in α-MEM and cells counted at 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 days. Passage-dependent expression of specific proteins was assayed for cells at passages 2 to 50, with about two population doublings corresponding to one passage.

To assay for fibroblast-like or chondrocyte-like markers, the clones were cultured in media supplemented with 10% FBS and hygromycin B (10μg/ml) for 2 days followed by incubation without hygromycin until the cells were ∼80% confluent. The cells were fixed for immunocytochemistry, and the expression of markers determined at the transcriptional and translational levels through qRT-PCR on mRNA and Western blots on cell lysates, respectively.

Multi-lineage Differentiation Potential of Cell Clones

The capacity for multi-lineage differentiation was determined for cell clones mTD-6 and -11. Cells were seeded at a density of 50,000/cm2 and initially maintained in α-MEM with 10% FBS. Osteoblast differentiation was induced by supplementing this media with 50μg/ml ascorbic acid, 10mM β-glycerophosphate and 3μM Chrion 99021 (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, Ml) for 21 days. For adipogenesis, cells were grown for 2 days in medium containing insulin (5μg/ml, Invitrogen), dexamethasone (1μM), IBMX (500μM) and troglitazone (5μM), followed by growth in medium containing troglitazone (5μM) only for up to 9 days. Chondrogenesis in multilayer cultures was induced over a 21-day period by addition of 50μg/ml ascorbic acid, 10mM β-glycerophosphate and 20μg/ml TGF-β1 (Enzo Life Science, Ann Arbor, Ml) to the medium.

Protein Assays and Western Blots

Immortalized clones were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) followed by ultrasonication (Sonic Dismembrator® model 10, Fisher Scientific). The protein concentration in the lysate was determined by BCA protein assay. The samples, standardized by total protein were mixed with 4X sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with 2-Mercaptoethanol, and separated by electrophoresis on 4-12% (w/v) Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Poly Acrylamide gels. The proteins were transferred to Polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immoblin®, Millipore), blocked with milk in PBS, incubated with primary polyclonal antibodies, washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad) as described previously28,31. Following further washes, the protein bands were visualized by incubating the membrane with a chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) and exposure to an X-ray film. After incubation with stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific) for 20 minutes, the blot was re-probed with primary antibody specific for actin.

Total RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

Gene expression levels were quantified by qRT-PCR (PRISM 7500, Applied Biosystems). Upon confluence, total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using Ominiscript RT kit (Qiagen) with an oligo(dT) primer (Applied Biosystems). A 1:100 (v/v) dilution of the resulting cDNA was utilized as the template to quantify the relative mRNA levels of FSP1, vimentin, COMP, collagen X, collagen II, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α (CEBP-α), adiponectin, runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and osteocalcin (OCN) using SYBR green master mix and specific primers designed with Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). All primers except those for OCN were obtained commercially (Applied Biosystems) and are proprietary information. The primer sequences for osteocalcin are provided in Figure 6. The qRT-PCR amplification was confirmed by performing the melting curve test and observing a single peak for each gene. Mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or β-actin was used as internal control.

Fig. 6. Fibroblast-like and chondrocyte-like mouse TMJ disc cell clones undergo osteogenic differentiation when cultured under appropriate conditions.

mTD-6 and -11 cell clones were cultured for up to 21 days in media alone (-) or media with osteogenic mediators (+) ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate and Chrion 99021. RNA was retrieved and subjected to qRT-PCR for Runx2 (A) and osteocalcin (B) or cells fixed and stained with Alizarin Red (C). Both cell types showed robust induction of osteogenic markers and mineralized matrix staining, with the differentiation being more marked for mTD-11 than mTD-6 cell clone. The primer sequence for OCN is as follows: Forward-GCTCTGTCTCTCTGACCTCACA; Reverse-CCCTCCTGCTTGGACATGAA; FAM Probe-CTGAGTCTGACAAAGCC. qRT-PCR data represents mean (95% CI) of respective genes relative to those of GAPDH from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Immunocytochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Immortalized clones were seeded into chamber slides (5 × 103 cells/chamber) until 30% confluent, washed with PBS, fixed with 75% (v/v) ethanol for 15 minutes, washed, incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed and blocked with 1% (w/v) horse serum albumin for 30 minutes. The cells were incubated with primary rabbit anti-mouse COMP or goat anti-mouse FSP1 or non-immune IgG for 2 hours. After washing, cells were incubated with fluorescent-labeled donkey anti-rabbit-FITC or donkey anti-goat lgG-CFL647 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) secondary antibody (1:2000v/v), respectively for 1 hour. The nuclei were stained with 4-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Following further washing, the cells were mounted with cover slips and observed under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon TS100, Tokyo, Japan). A similar protocol was used for staining TMJ disc tissue, with the exception that the sections were serially incubated with both primary antibodies followed by both secondary antibodies.

Cytochemistry for Cell Differentiation

The cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 1 hour, washed and processed as follows. For determination of fat droplet accumulation, the cells were incubated with 60% isopropyl alcohol for 10 minutes and stained with Oil Red O (2mg/ml in 60% Isopropyl Alcohol) for 1 hour. To stain for mineralization, the cells were incubated for 0.5 hour in 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.2 with 10% ammonium hydroxide). To stain for sulfated proteoglycans, the cells were incubated in 1% Alcian Blue in 3% acetic acid (pH 2.5) for 2 hours. Cells were washed with PBS and images taken using a phase contrast microscope (Nikon D300).

Statistical Analysis

All studies were performed in triplicate and repeated three-times. Numerical data were plotted as means ±95% confidence interval (CI). Because the data was normally distributed, the statistical significance of any differences was determined by single factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the inter-group differences were determined by Tukey's test using JMP 10 program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Cell Morphology Phenotypes and Location in the TMJ Disc and Knee Meniscus

We first quantified the relative numbers and distribution of the two cell types found in the TMJ disc based on morphology, and compared these findings with those of the knee meniscus fibrocartilage. As with other species, the mouse TMJ disc is biconcave in shape and can be similarly divided in the anteroposterior direction into an anterior band, intermediate zone, and posterior band (Figs. 1A and B). Although chondrocyte-like cells possessing a round morphology and surrounded by pericellular matrix were distributed throughout the disc, they were most abundant in the intermediate zone (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the elongated spindle shaped fibroblastic cells were mostly observed in posterior and anterior bands (Fig. 1D). Double immunolabeling revealed that most of the spindle shaped cells stained primarily for the fibroblast marker FSP132,33, while those with round morphology stained for both FSP1 and the chondrocyte marker COMP34 (Fig. 1E). Quantitation of the cell phenotypes by location showed that chondrocyte-like cells are dominant in the central region (70%) while fibroblast-like cells are more prevalent in the anterior and posterior bands (72%) of the disc (Fig. 1F). Overall 63% of the cells in the TMJ disc were of fibroblast-like morphology while the remainder were chondrocyte-like in shape. These findings contrast with those of the knee meniscus where chondrocyte-like cells predominate at over 90% of the cells (Fig. 1G).

Fig. 1. In vivo cell phenotypes in the mouse TMJ disc.

(A) H and E stained section of the TMJ showing the biconcave TMJ disc interposed between the mandibular condyle, and articular fossa and eminence. (B) Low power photomicrograph of the TMJ disc demonstrating cell distribution and heterogeneity of fibroblast-like (Fb-Like) and chondrocyte-like (Ch-Like) cells in the posterior band and intermediate zone of the TMJ disc. Although both cell types are found throughout the disc, the rounded chondrocyte-like cells with clear pericellular matrix are predominantly found in the central intermediate zone (C and F; white bars) while the elongated spindle shaped fibroblast-like cells are highly prevalent in anterior and posterior bands of the TMJ disc (D and F; black bars). (E) Double immunolabeling revealed that the spindle shaped cells stain primarily for FSP1 (red or magenta fluorescence; arrow), while the rounded cells stain for both COMP and FSP1 (yellow or white fluorescence; arrowhead). (G) The proportion of the two cell types differ between the TMJ disc and knee meniscus fibrocartilages with the TMJ disc (white bars) having a large proportion (62%) of fibroblast-like cells, while the knee meniscus (black bars) predominantly (90%) has chondrocyte-like cells. Data is presented as mean and 95% CI from three mice derived independently for each animal by averaging cell numbers from seven to ten sections per animal.

Immortalization and Cloning of Two Morphologically Different Cell Types from the TMJ Disc

Of 36 isolated hTERT cDNA-transfected clones, four demonstrated successful immortalization as determined by telomerase assays (Figs. 2A and B) and the stable expression of select markers for up to 50 passages (Fig. 2C). In contrast, no telomerase activity was observed in TMJ primary cells, and was almost completely inhibited in the clones after heat treatment, indicating that hTERT was competent in mouse cells (Figs. 2A and B). While primary TMJ disc cells had a progressive decrease in expression of versican and aggrecan with increasing cell passages, all established clones at passage 50 demonstrated expression levels of these proteins similar to those found in early passage primary cells (Fig. 2C), thus maintaining primary cell traits.

Fig. 2. Isolation, immortalization and initial characterization of mouse TMJ disc (mTD) cell clones.

Following transfection with a vector (pGNR145, ATCC) expressing the hTERT cDNA and selection with hygromycin, four clones demonstrated enhanced telomerase activity and stable expression of proteins over 50 passages. cDNA from cell clones transfected with hTERT subjected to telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay demonstrated robust increase in telomerase activity in mTD cell clones 1, 2, 6 and 11 relative to that in primary cells as determined by absorbance readings of amplified products (A), and telomere ladder on 12.5% Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide (B). This telomerase activity in hTERT-transfected cells was abrogated by heat inactivation (HI+). (C) The transfected cell clones also maintained stable expression levels of fibroblast marker versican, and chondrocyte marker aggrecan as well as MMP-9 and MMP-13 for up to 50 passages while a passage-dependent decrease in expression of these proteins was observed in primary disc cells. (D) At days 1 and 8 of culture mTD clones 2 and 6 show an elongated, spindle shaped fibroblast-like morphology, while mTD clones 1 and 11 demonstrated polygonal chondrocyte-like morphology. (E) All four cell clones had rapid growth curves reaching confluency at about 8 days, with mTD-2 and -6 showing faster growth rates than mTD-1 and -11 cell clones. Data is presented as mean with 95% CI. (***p< 0.0001)

Next the potential fibroblast-like or chondrocyte-like characteristics of the mouse TMJ disc (mTD) cell clones, mTD-1, -2, -6 and -11 were determined by cell morphology and growth curves. At pre-confluence (day 1) and confluence (day 8) clones mTD-2 and mTD-6 showed elongated, spindle shaped fibroblast-like morphology (Fig. 2D, a-d) while clone mTD-1 and mTD-11 are larger polygonal cells with large nuclei similar to those observed in chondrocyte-like cells (Fig. 2D, e-h). Additionally, mTD-2 and mTD-6 clones had faster growth rates than the mTD-1 and mTD-11 clones (Fig. 2E).

Confirmation of Fibroblast-like or Chondrocyte-like Characteristics of mTD Clones

The phenotypes of the mTD cell clones was determined by their relative expression of fibroblast markers, FSP1 and vimentin, and chondrocyte specific proteins, COMP and collagen type X by these cells. The clones mTD-2 and -6 had higher mRNA levels for FSP1 (>2.6) (Fig. 3A) and vimentin (>1.6) (Fig. 3B) compared to those in clones mTD-1 and -11. In contrast, mTD-1 and -11 clones had higher mRNA levels for COMP (>3.5 fold) (Fig. 3E) and collagen type X (>11 fold) than clones mTD-2 and -6 (Fig. 3F). These differences in expression of FSP1, vimentin, COMP and collagen X between the four cell clones was confirmed by Western blots (Figs. 3C and G) and by immunofluorescence for FSP1 and COMP (Figs. 3D and H). Given these observations, clones mTD-2 and -6 clones will be referred to as fibroblast-like, and clones mTD-1 and -11 as chondrocyte-like.

Fig. 3. Expression of fibroblast and chondrocyte markers in immortalized mTD cell clones.

mRNA or cell lysates extracted from immortalized cell clones were subjected to qRT-PCR or Western blots, respectively for fibroblast markers FSP and vimentin, as well as chondrocyte markers COMP, and collagen X. Fibroblast-like (Fb-Like) clones mTD-2 and -6 show higher gene and protein expression for FSP1 (A and C) and vimentin (B and C) than chondrocyte-like (Ch-Like) clones mTD-1 and -11. In contrast the chondrocyte-like clones show higher expression levels of COMP (E and G) and collagen X (F and G) than fibroblast-like clones. Actin was used as an internal control for qRT-PCR and Western blots. Immunocytochemistry revealed higher levels of FSP staining in fibroblast-like clones mTD-2 and -6 than chondrocyte-like clones mTD-1 and -11, (D) while COMP was more intensely stained in chondrocyte-like clones than fibroblast-like clones (H). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Actin was used as an internal control for the qRT-PCR and Western blots. qRT-PCR data represents mean (95% CI) fold difference in respective genes from three independent experiments for each cell clone, each performed in triplicate.

We also determined collagen I and II mRNA and protein expression in each clone and calculated the ratio of collagen type II:I mRNA levels. While both types of cell clones expressed similar levels of collagen type I mRNA, the chondrocyte-like clones expressed about two times higher mRNA levels of collagen type II than the fibroblast-like clones (Fig. 4A). This observation was confirmed by Western blots (Fig. 4B). Consequently, the chondrocyte-like clones showed more than three times higher collagen type II:I mRNA ratio compared with the fibroblast-like clones (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Expression of types I and II collagens by fibroblast-like and chondrocyte-like mTD cell clones.

Type I and type II collagen mRNA levels determined using qRT-PCR (A) and Western blots (B) showed that fibroblast-like clones mTD-2 and -6 (white bar) and chondrocyte-like clones mTD-1 and -11 (black bar) express similar levels of type I collagen. However, the chondrocyte-like cell clones expressed higher levels of collagen II than the fibroblast-like clones, which resulted in about a 3-fold greater type II: type I collagen mRNA ratio in the chondrocyte-like vs the fibroblast-like cell clones. Actin was used as an internal control for the qRT-PCR and Western blots. qRT-PCR data represents mean (95% CI) fold difference in respective genes from three independent experiments for each cell clone, each performed in triplicate.

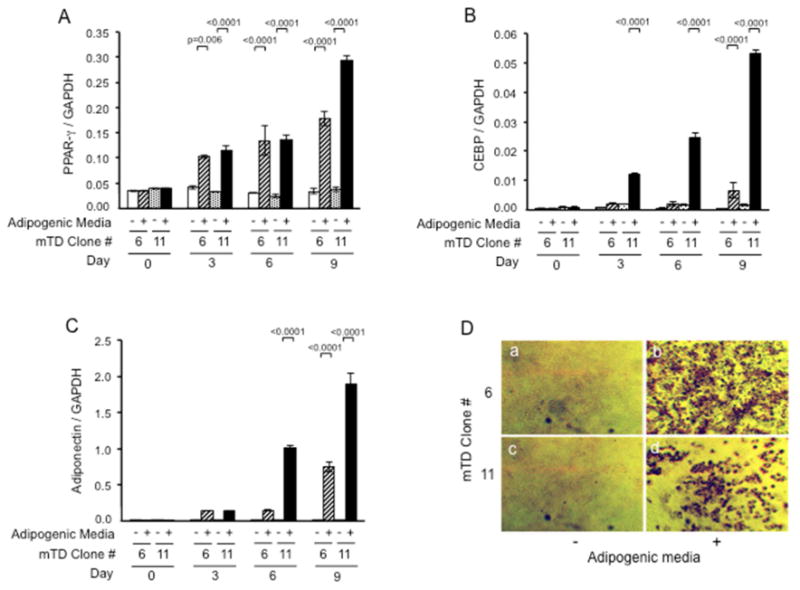

Multi-lineage Potential of mTD Cell Clones

To determine if the immortalized cell clones had a potential for multilineage differentiation we evaluated the ability of cell clones showing the highest levels of fibroblast markers (mTD-6) or chondrocyte markers (mTD-11) to differentiate to adipocytes, osteoblasts and chondrocytes. The basal levels of PPAR-γ, CEBP-α and adiponectin were similar in both cell clones (Fig. 5). In contrast, clone mTD-11 had higher baseline levels of osteogenic genes, Runx2 and OCN (Fig. 6) as well as chondrocyte marker collagen type X (Fig. 7) than clone mTD-6. Both cell clones demonstrated progressive and robust induction of adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic markers (Figs. 5 to 7). With the exception of Runx2, for which both cell clones responded similarly to osteogenic induction in the first 14 days, the mTD-11 clone had greater and / or earlier induction of all markers of adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation than clone mTD-6. Staining for adipogenesis with Oil Red O demonstrated marked uptake of dye by both adipocyte-induced cell clones, with mTD-11 showing more enlarged cell size and lipid accumulation than mTD-6. Similarly, staining for mineralization and sulfated proteoglycans showed deeper coloration and larger nodules in mTD-11 than mTD-6 cell clones. Thus overall mTD-11 clone has a greater mesenchymal multipotential differentiation capacity than the mTD-6 clone.

Fig. 5. Fibroblast-like and chondrocyte-like mouse TMJ disc cell clones undergo adipogenic differentiation when cultured under appropriate conditions.

mTD-6 and -11 cell clones were cultured for up to 9 days in media alone (-) or media with adipogenic mediators (+) insulin, dexamethasone, IBMX and troglitazone. RNA was retrieved and subjected to qRT-PCR for PPAR-y (A), CEPB-oc (B) and adiponectin (C) or cells fixed and stained with Oil Red-O (D). Both cell types showed robust induction of all adipogenic markers and Oil Red-O staining under adipogenic conditions, with the differentiation being more marked for mTD-11 than mTD-6 cell clone. qRT-PCR data represents mean (95% CI) of respective genes relative to those of GAPDH from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Fig. 7. Fibroblast-like and chondrocyte-like mouse TMJ disc cell clones undergo chondrogenic differentiation when cultured under appropriate conditions.

mTD-6 and -11 cell clones were cultured for up to 21 days in media alone (-) or media with chondrogenic media (+) ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate and TGF-β1. RNA was retrieved and subjected to qRT-PCR for type II collagen (A) and type X collagen (B) or cells fixed and stained with Alcian Blue (C). Both cell types showed robust induction of chondrogenic markers and sulfated proteoglycan staining, with the differentiation being more marked for mTD-11 than mTD-6 cell clone. qRT-PCR data represents mean (95% CI) of respective genes relative to those of GAPDH from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Discussion

Our study is the first to immortalize, clone and characterize two distinct types of TMJ disc cells. The successful immortalization of the cells was demonstrated by the similarly high levels of telomerase activity in all four clones and the stability of versican and aggrecan expression for upto 50 passages. In contrast to the immortalized cell clones, primary cells showed little telomerase activity and progressive decrease in expression of the assayed proteins. This effect of passaging on diminution of protein expression in primary cells has been shown in previous studies including those from the human TMJ disc35,36. Thus passaging of TMJ fibrochondrocytes retrieved from diseased human TMJs over 9 passages resulted in passage-dependent decrease in cell viability and reduction in expression of genes for several matrix molecules including collagens I, III, IV, V, XV and XVI, the proteoglycans aggrecan, chondroitin sulfate, heparin sulfate, biglycan, decorin, and COMP36. Similarly, porcine primary TMJ disc cells undergo significant decreases in gene expression levels of aggrecan, and collagen types I and II by 20%, 23% and 73%, respectively per passage35. The successful immortalization and cloning of disc cells provides a valuable resource for studying the behavior of specific cell subtypes in health and disease.

Our findings confirm the presence of at least two cell populations within the mouse TMJ disc that have different morphologies and express different levels of fibroblastic and chondrocytic genes. The isolation of cells with two distinct morphologies from the TMJ disc is not surprising given that the tissue has a heterogenous cell population, and validates previous studies where two cell phenotypes were observed in mixed cell cultures31. Cells within the TMJ disc have been variously identified as fibroblasts, fibroblast-like, fibrochondrocytes, chondrocyte-like and chondrocytes12,20,23-26,37,38 emphasizing that the nature and behavior of these cells remain poorly understood. In supplementing the current knowledge on these cells, our in vivo characterization of cell types by morphology showed that the TMJ disc from young mice has approximately 63% fibroblast-like cells and 37% chondrocyte-like cells, with the former cells predominantly located in the peripheral zones while the majority of the latter cell type were found in the intermediate zone. These findings compare well with those from the porcine TMJ disc where approximately 70% of the cells have fibroblast-like and remainder have chondrocyte-like morphologies38. Regionally too the ratio of fibroblast-like to chondrocyte-like cells is higher in the anterior and posterior bands and lower in the intermediate zone in bovine and porcine discs23,38. In contrast to the cell types in the porcine and mouse disc, the TMJ disc cells of the primate contain numerous chondrocytes in the band areas while the intermediate zone is tendinous with scattered chondrocytes and the posterior attachment is composed of fibrocytes39. Similarly in rabbits, cartilage-characteristic proteoglycans and cartilage-like cells are located in the band areas with those in the attachment region showing fibroblastic characteristics40. Taken together our findings and those of others12,20,23-25,38-41 demonstrate that the TMJ disc is a microheterogenous tissue with distinct areas of regional specialization and substantial variations between species.

The finding on differences in the tissue localization of cell phenotypes and matrix distribution and composition between species likely reflects species-dependent dissimilarities in functions to which the disc is subjected and age related changes of the discal tissues12,16,20,23-25,38-41. Fibrocartilages in general including the TMJ disc have been referred to as a transitional tissue19 that undergo substantial regional and temporal developmental and maturational changes in composition, organization and cell phenotype with age. Mechanical forces play a key role in the maturation of the TMJ fibrocartilage as well as to changes in its composition and anatomy. Thus the full maturation of the TMJ disc coincides with functional demands when adult occlusion is established14 and the transition from a primarily fibrous tissue in young rats and marmosets to one containing fibrochondrocytes in older animals12. Finally, the evidence for the potent effects of function on disc anatomy, composition, and cells is provided by experiments in which joint loading is altered13,15,30. For example raising the bite unilaterally in animal models results in increased expression of aggrecan in disc fibrocartilage indicating that increased compressive bite forces contribute to regional changes in the TMJ fibrocartilage13,15. These experiments also reveal that the disc cells are highly and rapidly responsive to changes in the mechanical environment as reflected by the robust regional changes in disc glycosaminoglycan content as early as 2 to 4 weeks following altered TMJ loading. Similarly, a pathologic model of disc displacement in rabbits shows rapid extensive shape changes, reorganization of collagenous matrices and loss of metachromatic staining40. Given that these responses of the disc to physiologic stimulation or pathologic insult are modulated by discal cells, the availability of two types of immortalized cell clones creates opportunities to explore and dissect the specific responses of different cell subtypes to altered biological and / or mechanical environments.

The multi-potential differentiation capabilities under adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic conditions of both the fibroblast- and chondrocyte-like cell clones demonstrate that they retain plasticity and have not yet acquired an irreversible differentiation status. While cells with multi-lineage potential have not been isolated from the TMJ disc previously, it is possible that the disc maintains a pool of such cells for self-repair and regeneration. As such a preferential selection of progenitor cells during immortalization and clonal expansion provides a likely explanation of these traits in our cell clones. The presence of this multipotent quality in at least cell clones mTD-6 and -11 offers a potential resource for future animal studies on defining viable tissue engineering approaches for TMJ disc fibrocartilage regeneration. Also a single established TMJ phenotype may not offer the plasticity required for responding to changes in function and mechanical environment to undergo the desired differentiation. This makes it important for some cells within the tissue to retain the capacity to undergo differentiation into the range of cells typically present within the tissue. Although tissue engineering of bone and cartilaginous tissues have been well studied, that of the complex heterogenous TMJ disc is still in relatively early stages. Much of the research on tissue engineering the TMJ disc has focused on characterizing the native tissue composition, organization and mechanical properties, and identifying appropriate scaffolds and testing cell types and densities20,37,38,43-50. However despite some initial work49,50, no cell type(s) or source has yet been validated for reconstituting an optimal fibrocartilaginous TMJ disc. The immortalized TMJ disc fibroblast-like and chondrocyte-like cell clones with multi-potential differentiation capabilities generated from our studies will provide the ability to both compare their relative efficacies in tissue engineering of the TMJ disc and provide insights into how to improve TMJ disc repair and regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data: Comparative expression of Fibroblast Specific Protein 1 (A) and COMP (B) in early passage (P2) primary TMJ disc cells and cell clones mTD-6 and -11. (C) Immunolocalization of type X collagen in mouse TMJ disc.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants R01 DE018455 and K12 DE023574 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. We wish to thank Dr. Takayuki Hayami for his help with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors state that they have no conflicts of interests.

- Sunil Kapila and Young Park conceived and designed the studies;

- Young Park, Jun Hosomichi, Chunxi Ge and Jinping Xu collected and assembled the data;

- Sunil Kapila, Young Park, Jun Hosomichi, Chunxi Ge and Renny Franceschi contributed to analysis and / or interpretation of the data;

- Young Park and Jinping Xu provided technical and logistical support;

- Sunil Kapila obtained funding for these studies;

- All authors contributed to drafting or revising the article for important intellectual content;

- All authors read and provided final approval for the submitted manuscript.

Competing Interest Statement: None of the authors have any financial or personal conflict of interest or competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Howard J, Truelove E, et al. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120:273–281. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1990.0043. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohrbach R, Fillingim RB, Mulkey F, Gonzalez Y, Gordon S, Gremillion H, et al. Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain. 2011;12:T27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;124:115–21. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manfredini D, Segu M, Bertacci A, Binotti G, Bosco M. Diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders according to RDC/TMD axis I findings, a multicenter Italian study. Minerva Stomatol. 2004;53:429–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plesh O, Sinisi SE, Crawford PB, Gansky SA. Diagnoses based on the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders in a biracial population of young women. J Orofac Pain. 2005;19:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortes D, Exss E, Marholz C, Millas R, Moncada G. Association between disk position and degenerative bone changes of the temporomandibular joints: an imaging study in subjects with TMD. Cranio. 2011;29:117–26. doi: 10.1179/crn.2011.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhard L, Giannakopoulos NN, Rohde S, Schmitter M. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disc position in patients with TMJ pain assessed by coronal MRI. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42:201. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos KC, Dutra ME, Warmling LV, Oliveira JX. Correlation among the changes observed in temporomandibular joint internal derangements assessed by magnetic resonance in symptomatic patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1504–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka E, Dalla-Bona DA, Iwabe T, Kawai N, Yamano E, van Eijden T, et al. The effect of removal of the disc on the friction in the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1221–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carini F, Scardina GA, Caradonna C, Messina P, Valenza V. Human temporomandibular joint morphogenesis. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2007;112:267–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sperber GH. Craniofacial Development. BC Decker; Hamilton, ON: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkovitz BK, Pacy J. Age changes in the cells of the intra-articular disc of the temporomandibular joints of rats and marmosets. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:987–95. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao JJ, Rahemtulla F, Scott PG. Proteoglycan expression in the rat temporomandibular joint in response to unilateral bite raise. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1520–28. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagy NB, Daniel JC. Development of the rabbit craniomandibular joint in association with tooth eruption. Arch Oral Biol. 1992;37:271–80. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(92)90049-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakao Y, Konno-Nagasaka M, Toriya N, Arakawa T, Kashio H, Takuma T, et al. Proteoglycan expression is influenced by mechanical load in TMJ discs. J Dent Res. 2015;94:93–100. doi: 10.1177/0022034514553816. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano T, Scott PG. Changes in the chemical composition of the bovine temporomandibular joint disc with age. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:845–53. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(96)00040-4. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beek M, Koolstra JH, van Ruijven LJ, van Eijden TM. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of the cartilaginous structures in the human temporomandibular joint. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1913–18. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800101001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beek M, Aarnts MP, Koolstra JH, Feilzer AJ, van Eijden TM. Dynamic properties of the human temporomandibular joint disc. J Dent Res. 2001;80:876–80. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. Biology of fibrocartilage cells. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;233:1–45. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Detamore MS, Athanasiou KA. Structure and function of the temporomandibular joint disc: implications for tissue engineering. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:494–506. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano T, Scott PG. A quantitative chemical study of glycosaminoglycans in the articular disc of the bovine temporomandibular joint. Arch Oral Biol. 1989;34:749–57. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(89)90082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scapino RP, Canham PB, Finlay HM, Mills DK. The behaviour of collagen fibres in stress relaxation and stress distribution in the jaw-joint disc of rabbits. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:1039–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(96)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landesberg R, Takeuchi E, Puzas JE. Cellular, biochemical and molecular characterization of the bovine temporomandibular joint disc. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:761–67. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(96)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milam SB, Klebe RJ, Triplett RG, Herbert D. Characterization of the extracellular matrix of the primate temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:381–91. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90376-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills DK, Daniel JC, Herzog S, Scapino RP. An animal model for studying mechanisms in human temporomandibular joint disc derangement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:1279–92. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rees LA. The structure and function of the mandibular joint. Br Dent J. 1954;96:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonardi R, Musumeci G, Sicurezza E, Loreto C. Lubricin in human temporomandibular joint disc: an immunohistochemical study. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:614–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad N, Wang W, Nair R, Kapila S. Relaxin induces matrix-metalloproteinases-9 and -13 via RXFP1: induction of MMP-9 involves the PI3K, ERK, Akt and PKC-z pathways. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;363:46–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Hayami T, Kapila S. Female hormone receptors are differentially expressed in mouse fibrocartilages. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:646–54. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sindelar BJ, Evanko SP, Alonzo T, Herring SW, Wight T. Effects of intraoral splint wear on proteoglycans in the temporomandibular joint disc. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;379:64–70. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapila S, Lee C, Richards DW. Characterization and identification of proteinases and proteinase inhibitors synthesized by temporomandibular joint disc cells. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1328–3640. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740061301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, et al. Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:393–405. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada H, Danoff TM, Fischer A, Lopez-Guisa JM, Strutz F, Neilson EG. Identification of a novel cis-acting element for fibroblast-specific transcription of the FSP1 gene. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(2):F306–14. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.2.F306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaucke F, Dinser R, Maurer P, Paulsson M. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) and collagen IX are sensitive markers for the differentiation state of articular primary chondrocytes. Biochem J. 2001;358:17–24. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen KD, Athanasiou KA. Effect of passage and topography on gene expression of temporomandibular joint disc cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:101–10. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garzon I, Carriel V, Marin-Fernandez AB, Oliveira AC, Garrido-Gomez J, Campos A, et al. A combined approach for the assessment of cell viability and cell functionality of human fibrochondrocytes for use in tissue engineering. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen KD, Athanasiou KA. Tissue Engineering of the TMJ disc: a review. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1183–96. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Detamore MS, Hegde JN, Wagle RR, Almarza AJ, Montufar-Solis D, Duke PJ, et al. Cell type and distribution in the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:243–48. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills DK, Fiandaca DJ, Scapino RP. Morphologic, microscopic, and immunohistochemical investigations into the function of the primate TMJ disc. J Orofac Pain. 1994;8:136–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mills DK, Daniel JC, Scapino R. Histological features and in-vitro proteoglycan synthesis in the rabbit craniomandibular joint disc. Arch Oral Biol. 1988;33:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(88)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalpakci KN, Willard VP, Wong ME, Athanasiou KA. An interspecies comparison of the temporomandibular joint disc. J Dent Res. 2011;90:193–98. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segu M, Politi L, Galioto S, Collesano V. Histological and functional changes in retrodiscal tissue following anterior articular disc displacement in the rabbit: review of the literature. Minerva Stomatol. 2011;60:349–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Almarza AJ, Athanasiou KA. Seeding techniques and scaffolding choice for tissue engineering of the temporomandibular joint disk. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1787–95. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen KD, Athanasiou KA. Scaffold and growth factor selection in temporomandibular joint disc engineering. J Dent Res. 2008;87:180–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almarza AJ, Athanasiou KA. Effects of initial cell seeding density for the tissue engineering of the temporomandibular joint disc. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:943–50. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-3311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almarza AJ, Athanasiou KA. Evaluation of three growth factors in combinations of two for temporomandibular joint disc tissue engineering. Arch Oral Biol. 2006;51:215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Detamore MS, Athanasiou KA. Tensile properties of the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:558–65. doi: 10.1115/1.1589778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Detamore MS, Athanasiou KA. Effects of growth factors on temporomandibular joint disc cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:577–83. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalpakci KN, Kim EJ, Athanasiou KA. Assessment of growth factor treatment on fibrochondrocyte and chondrocyte co-cultures for TMJ fibrocartilage engineering. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:1710–18. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang L, Detamore MS. Effects of growth factors and glucosamine on porcine mandibular condylar cartilage cells and hyaline cartilage cells for tissue engineering applications. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Data: Comparative expression of Fibroblast Specific Protein 1 (A) and COMP (B) in early passage (P2) primary TMJ disc cells and cell clones mTD-6 and -11. (C) Immunolocalization of type X collagen in mouse TMJ disc.