Abstract

As the number of prison inmates facing end-stage chronic illness grows, more prisons across the U.S. must address the need for end-of-life care. Many will likely need to develop a plan with potentially limited resources and external support. This case study presents one long-running model of care, the Louisiana State Penitentiary Prison Hospice Program. Based on field observations and in-depth interviews with hospice staff, inmate volunteers and corrections officers, we identify five essential elements that have contributed to the long-term operation of this program: patient-centered care, an inmate volunteer model, safety and security, shared values, and teamwork. We describe key characteristics of each of these elements, discuss how they align with earlier recommendations and research, and show how their integration supports a sustained model of prison end-of-life care.

Keywords: prison hospice, end-of-life care, palliative care, correctional health

Introduction

The number of elderly and aging prisoners in the U.S. is rapidly increasing1-3, and prison inmates as a group experience greater disease burden and worse health outcomes than community-dwelling adults. Inmates have higher prevalence of infectious diseases,4 chronic and comorbid illness,5-8 higher rates of cancer generally and of more aggressive forms of cancer particularly,9 greater age-related disability,10-11 and more mental health and substance use disorders.12-14 They may not only experience higher rates of dementia15-16 but the resulting cognitive and physical dysfunction has a greater impact on incarcerated older adults because of the lack of accommodation and adaptability that characterizes prison settings.10-11, 17

In addition to lengthy prison sentencing practices that have raised the number of U.S. prisoners serving longer or life sentences, these findings highlight two additional facts. First, older adults in prison experience a disproportionately greater illness burden then their community-dwelling counterparts.18 Second, a greater number of incarcerated prisoners will experience life-limiting illness, and will die as a result of chronic illness, than ever before in U.S. history.1 Correctional health programs in every state will be required to address the need for end-of-life care for an exponentially growing number of inmates. How to adequately address this need, and provide constitutionally-mandated and humane care while balancing security and custodial demands, will become an increasingly pressing problem for those systems that have not already initiated measures to increase capacity for end-of-life care.

To meet this growing need, prisons in a number of states have implemented prison hospice programs to deliver end-of-life care to incarcerated patients. Hoffman and Dickinson report that in 2011 there were 69 prison hospices operating in the U.S.,19 a number is difficult to confirm as it is derived from self-report by institutional representatives rather than direct observation. Moreover, there is a considerable variety in terms of what activities and policies may be labeled as prison hospice or the models used to deliver these services. For example, prison hospice programs vary greatly in resources, organizational features, and approaches to end-of-life services; there are programs that involve inmate volunteers more or less extensively, programs that bring in outside service providers, and those that train their own medical staff in hospice care. Some programs have developed designated hospice units, and other deliver end-of-life care in general population or in infirmaries.20 It is also likely that there are correctional institutions that have made no provisions for hospice or end-of-life care, and no public documentation informs us whether these are in the minority or majority.

While the literature base for prison hospice is more than 15 years old and includes at least two sets of guidelines for best practices authored by national organizations21-22 there are still relatively few published data-based studies of prison hospice. A series of articles published in the hospice and palliative care literature from 2000 to 2002 describe the development and implementation of the Louisiana State Penitentiary (LSP) Prison Hospice Program at Angola, including the reasons this program was developed, anecdotal accounts of its implementation, and the participation and reaction of correctional officers (COs), medical and nursing staff and inmates.23-26 Other articles describe impressions of the program27, 28 In 2003 Yampolskaya and Winston identified principal components of prison hospice programs based on survey of the literature and extant resources and phone interviews with 10 representatives of U.S. prison hospice programs.29 In a similar 2007 study, Wright and Bronstein conducted phone interviews with 14 U.S. prison hospice coordinators and reported on organizational and structural features, particularly the role of the interdisciplinary treatment team (IDT), that foster integration of prison hospice with the larger institution and culture.30 Most recently, a team of nurse researchers in Pennsylvania have reported on administrative, health staff and patient needs regarding the implementation of end of life care in that state prison system, including the role played by informal inmate volunteers.31-33

The LSP prison hospice program, established in 1998, is among the longest continuously running prison hospice program in the US. Since its inception, other correctional systems have sent representatives to tour their program and learn how the program operates; two film documentaries have also made the program visible to a wider public. This program, therefore, has been considered a case model for the delivery of sustainable prison hospice services. Beginning in 2011, our team engaged in research, in partnership with LSP Prison Hospice staff and inmate volunteers, to identify and describe essential features of this program that contribute to its effectiveness, longevity and sustainability.20,33-34 The study reported here is part of this project to investigate a long-running prison hospice program, examine how it incorporates a unique peer-care inmate volunteer model to deliver end-of-life care to inmates with life-limiting illness, and evaluate outcomes for both patients and inmate volunteer participants.

Study Purpose

The present study sought to describe those factors that LSP hospice staff, inmate volunteers and COs view as essential to supporting the effective and sustained provision of prison hospice services, based on empirical data gathered from field research case-study methods including site visits, observation, and in-depth interviews.

Methods

Design

This qualitative case study was guided by grounded theory principles of deriving evidence from in-depth analysis of everyday practices in their local, situated context. We focused on how interactions among those involved in prison hospice, within the specific context of the prison setting, culture and overarching policies, shaped the ecology of the prison hospice program, and how this influenced sustainability. All study activities were approved by the University's Institutional Review Board.

Description of LSP Hospice Program

The Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola (LSP) serves a population of more than 5000 male inmates at varying levels of custody from minimum to supermaximum status. The majority of LSP inmates are African American and many are serving life sentences as Louisiana State has among the strictest sentencing laws in the U.S.

The prison hospice program, began in 1998, has been in continuous operation, and from 1998 through September 2014 has provided care for 227 patients. Located within a long-term care unit in the LSP treatment center, six private cells are dedicated to hospice care and more beds available as needed in the central common space. Their interdisciplinary treatment team, two RNs serving as hospice director and coordinator, physicians, a unit social worker and several chaplains of different faiths, organizes the supervision, delivery and management of care.

The program relies on a peer-care model where trained inmate volunteers deliver direct, hands-on care of hospice patients. Inmates interested in volunteering submit an application to the LSP Hospice Coordinator, who then consults formally and informally with COs and inmate volunteers about the suitability of each applicant. Those who are green-lighted are interviewed by the coordinator and social worker; those selected then undergo a training program that includes didactic education, shadowing experienced volunteers, and supervised hands-on experience. When a patient is admitted, volunteers are matched with each patient and assigned to provide 1:1 care throughout the duration of the patient's hospice stay. Inmate volunteers provide most aspects of direct patient care, including activities of daily living and the prevention of skin breakdown. They observe for patient symptoms, including pain, and provide non-pharmacologic interventions such as massage, redirection, relaxation techniques, and repositioning. Inmate volunteers also provide social, psychological and spiritual support for their assigned patients. A hallmark of the program is that when a patient nears death, a vigil is initiated in which inmate volunteers maintain constant presence at the patient beside until the patient dies.

Correctional staff coordinate with hospice team members on a daily basis to support the provision of key program elements such as movement of inmate volunteers from population to the unit to provide patient care, patient visits from family (both biological and prison family), regular volunteer program meetings and fundraising activities, program tours, and patient after-care activities such as funeral arrangements and remembrance services.

Sample

We employed purposeful sampling to solicit interview participants from among COs, medical and nursing staff, and inmate hospice volunteers, based on their ability to inform and expand our understanding of the history of the program and the essential elements necessary to its everyday operation, management and sustainability. Interview participants represented varied roles, level of expertise, training, education, and years working at or living in the prison.

Data Collection

Data included formal interviews, informal conversations with COs, medical staff (RNs, LPNs, CNAs, physicians), hospice administrators, inmate hospice volunteers and prison administration officials, observations and notes made during four site visits to the LSP Prison Hospice Program from August 2011-March 2013. In addition to observations made on the unit and informal conversations, we conducted formal, in-depth interviews with 43 participants including 5 COs, 14 medical and hospice staff, and 24 inmate volunteers. Interviews ranged from 25 minutes to 75 minutes. Some hospice staff and inmate volunteer participants were interviewed more than once, 9-12 months after the first interview. This provided a means for member-checking our interpretation of these data, and incorporating feedback into our analysis. Research interviews were audio recorded (only two participants—both staff members—declined to be recorded.)

Data Analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy, cleaned and imported into Nvivo 10 for coding. Based on team discussion a codebook was developed with seventeen primary content codes; two research team members applied primary codes to each transcript using a line-by-line approach. Ensuring adequate coverage of this complex data was the primary goal at this stage, so coders applied simultaneous coding,35 assigning more than one primary code to the data to fully describe the content. The research team conferred after each coding cycle to discuss and clarify any differences in the application of these codes.

Frequency counts were run for all primary codes by group (staff, inmates and COs), to generate a list of the codes occurring most often in each group; this list was then compared across groups, and seven codes were identified as those most frequently cross-cutting data in all three groups. Data labeled with these codes were aggregated within all three groups, and subsequent phases of team review and discussion identified emergent secondary codes which were then used to perform line-by-line coding on data in these cross-cutting categories. In subsequent analysis, categories were integrated until the final central concepts emerged. Throughout, we constantly compared portions of interview texts and coding within and between participants, and with observational data.

Findings

Five central categories emerged from analysis of interviews and other case-study data: patient-centered care, the volunteer model, safety and security, shared values, and teamwork. These categories are foundational components of the core category essentials of sustainable prison hospice as they were recounted by the COs, hospice staff and inmate volunteers. In what follows we present overarching features of these five essential categories, including similarities and differences associated with differing LSP hospice program roles, and provide tables linking their core components with definitions and exemplary quotes.

Patient-Centered Care

One of the first essential cross-cutting concepts identified was patient-centered care. This is a familiar term to many health providers across multiple settings, yet it assumes a different constellation of meanings in relation to end-of-life care in a prison hospice. Table 1 summarizes the four key concepts that describe the dimensions of patient-centered care and its meaning within this context: unconditional care, responsiveness, authentic relationships and knowing your patient.

Table 1.

Essential elements of prison hospice: Patient-centered care

| Patient-Centered Care | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concepts in Context | Definition and Dimensions | Exemplary Quote |

| Unconditional care | Every prison hospice patient deserves humane care and should be treated with respect regardless of a patient's history or circumstances; acknowledgement of the humanity and uniqueness of each hospice patient, and the need to support and maintain dignity at end-of-life. | “I'm not here to judge anybody. When you're dying, you need somebody to care about you. I'm a nurse. I'm not a judge.” (Nurse) |

| Responsiveness | Alleviating patients' symptoms in a timely way and taking other measures to prevent unnecessary suffering due to their illness process; willingness to respond not only to patient needs but to other team members' assessments and requests. | “A change with their pain medicine, [the nurse is] right there. And she's doing it. Or [a patient] wants to talk to family, something's going on. They're calling me.” (Nurse) |

| Forming real relationships | Being fully present whenever a volunteer is at the bedside and engaged in patient care, and being fully available and open, physically, cognitively, emotionally, and spiritually, to the experience of providing end-of-life care. Therapeutic relationships provide comfort and were supported by establishing trust with patients (and staff), as well as learning to establish and maintain appropriate boundaries. | “I let my patients know that...I'm here for you at all times. And whenever you need me to talk, man, I don't care what it is, if you just need me to come in there, you want to cry on my shoulder, I'm here for you. I want you to feel that you can trust with anything you tell me.” (Volunteer) |

| Know your patient | Specific in-depth knowledge of each patient, as an individual person, to optimize care; includes sharing knowledge about each patient, forming relationships early on, nurturing those relationships, and knowing how to “read” individual patients in order to accurately assess for changes in status, pain, and mood. | “You come in contact with so many different people with various personalities and you can never treat each individual the same. But as long as you have the ability to empathize and sensitivity to listen to what your patient is saying, it will be easier to adapt to those conditions.” (Volunteer) |

Unconditional care

Unconditional care was a critical component identified by all three groups, although how each group conceptualized it depended on their primary role and how closely they interacted with hospice patients. Many hospice staff and COs shared the view that a patient's incarceration was their just punishment, not the adequacy of treatment or care they received while incarcerated. Inmate volunteers described unconditional care in terms of providing care of equally high quality to all their patients, regardless of race, social affiliation, religious belief (or non-belief), criminal history or personal characteristics.

Responsiveness

Hospice staff, including CNAs, LPNs, and RNs, described patient-centered care as a patient-specific approach to addressing patient needs, including proactive symptom management based on expert assessment, responding to individual needs whenever possible, and patient advocacy. Staff also described a willingness among medical staff, volunteers and COs to change scheduling or unit routines in order to accommodate patient needs.

Forming real relationships

Mentioned most often by the volunteers, forming real relationships meant being fully present when at the bedside and engaged in patient care. This was supported by establishing trust with patients (and staff), while maintaining appropriate boundaries. The prison setting presents barriers to COs and staff having such relationships with hospice patients, and volunteers were better suited to this role; staff and COs recognized the importance of these relationships and the commitment of volunteers in fostering them.

Knowing your patient

This was described by volunteers as a critical lesson learned through experience, and by watching other volunteers in “a continuing process of learning” though which they understood the critical need to get to know and communicate with patients before they become too ill to engage. The need to have extensive understanding of each hospice patient as an individual was described in ethical terms, as essential for the provision of optimal care.

The Inmate Hospice Volunteer Model

The volunteer model was recognized by staff, COs, and volunteers as a critical and unique component of the LSP Prison Hospice Program and the primary reason end-of-life care services have been sustained. Table 2 presents four key features related to the volunteer model: peer-to-peer care, direct 1:1 care, the distinction between volunteers and orderlies, and a high level of education and experience.

Table 2.

Essential elements of prison hospice: The inmate hospice volunteer model

| Inmate Hospice Volunteer Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concepts in Context | Definition and Dimensions | Exemplary Quote |

| Peer-to-peer care | Use of inmate volunteers to provide direct end-of-life care to their peers. The connection volunteers share with their fellow inmates facilitates quality continuity of care; volunteers identify with and advocate for patients, are resourceful and find innovative ways to meet patient and unit needs. | “They'll [volunteers] even tell us things like, he's depressed, and they'll know the reason why. You know, it may be something going on in his life that we don't know about.” (Nurse) |

| Direct 1:1 care | Volunteers receive 1:1 patient care assignments that begin upon admission; provide a wide range of direct patient-care activities encompassing clinical, emotional, spiritual, and after-care; also includes being on call 24/7 during vigil, performing symptom and pain assessment, innovative non-pharmacological symptom and management techniques. Volunteers do all of the bedside care, with the exception of taking vital signs, testing blood sugar and administering medication, extending the staffing model to relieve nurses of such care; nurses rely on volunteers to be their “eyes and ears”. | “The nurse is not there to sit and just watch the patient. You got to be the one to sit there, you got to watch the oxygen tanks and...whether he's in pain, so you got to be able to communicate with the nurse.” (Volunteer) |

| Beyond orderlies | Differentiating unpaid volunteer role from orderlies who may receive compensation; key characteristics of the volunteer role include: being surrogate family; taking a team approach; dedication (i.e. volunteering during free time and being available on-call); considered the backbone of the program. Volunteers demonstrate dedication by keeping their word with patients, choosing to care for patients during their free time, often missing other recreational and social opportunities to attend their patients. | “Well, the orderly, he doesn't have to care about you. And if you need a shower, all he has to do is...shower you...put you back in the bed, and he's gone. It's like it's no relationship there...That's the whole point of not dying alone, knowing that somebody is there, that have to do that role.” (Volunteer) |

| Education/experience | Volunteers are highly trained; receive ongoing formal education (hospice education, clinical psychology, spiritual) and in-services, as well as informal education through hands-on apprenticeships or mentorships with experienced volunteers. Volunteers also deliver education to patients and to others outside the hospice program; volunteers often speak at conferences and participate in radio shows. | “I watched the guy that I knew was sincere...and when I tutored I got a little bit from this one and a little bit from that one. And I acquired what I knew, and became the volunteer that I am today.“ (Volunteer) |

Peer-to-peer care

The provision of peer-to-peer care was described as enabling an extent and quality of end-of-life care that would not otherwise be possible given the setting and circumstances. Volunteers are able to identify and empathize with prison hospice patients, to advocate for their social, emotional and spiritual needs based on shared understanding, and to “translate” between patients and hospice staff. Staff and COs recognize that hospice patients may feel more comfortable relating to another inmate who may share similar experiences while also being skilled in providing care.

Direct 1:1 care

Provision of patient-centered hospice care was possible due to 1:1 patient care assignments. Volunteers were able to invest the time required to monitor patients continuity of care while providing the majority of direct bedside care including sitting 24-hour vigil at time of death and aftercare. Extending the staffing model in this manner enabled nursing staff to focus on management, medication administration, attend to specialized care, and be a resource for volunteer questions. Staff frequently spoke about their reliance upon volunteers to be their “ears and eyes”, often deferring to volunteers for their expert knowledge of patients and ability to recognize patient-specific symptoms.

Beyond orderlies

Participants also frequently pointed out that volunteers work for free, providing care in addition to their regularly assigned work within the prison. This represented an exceptional dedication and commitment to their role, the program, and most importantly, their patients. This was often contrasted with the role of an inmate orderly, who is assigned to work in the treatment unit and who may receive compensation for this work.

Education and experience

In addition to over 40 hours of initial didactic and supervised hands-on clinical training, volunteers participate in ongoing formal education courses based on modified CNA trainings that provide essential elements of providing care. More experienced volunteers—some having provided end of life care for dozens of patients over more than a decade— commonly mentored newer volunteers on patient care. Notably, volunteers placed highest value on informal, hands-on experiences they received on the job working with other volunteers, learning things beyond the basics learned in books.

Safety and Security

There are always potential conflicts between institutional mandates of security and the provision of patient care, yet our study participants discussed a nuanced sense of how missions of security and end-of-life care can—and must—be balanced and integrated. Table 3 details three foundational aspects related to safety and security: security first, boundaries not barriers, adaptability, and a focus on patient safety.

Table 3.

Essential elements of prison hospice: Safety and security

| Safety and Security | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concepts in Context | Definition and Dimensions | Exemplary Quote |

| Security first | This idea is foundational not only because it is a prison, but because this orientation allows them to make this a special space within the prison where hospice can happen; includes the idea of the prison as context or environment, the prison code, protecting the program, and securing the space for hospice (keeping hospice a safe place). | “If they see an issue or something somebody will jump on it real quickly because we want it to run smooth. We don't want the name smeared in any way...we try to clear up anything that goes on. But it's mainly everybody is very proud of it.” (Nurse) |

| Boundaries not barriers | Not allowing typical boundaries like protocol, procedures, and policies to become barriers to allowing hospice to function; maintaining “fair but firm” professional boundaries while also treating others with respect and avoiding rigidity; examples include allowing touch between inmates, and having clear expectations. | “I think they're [volunteers] given a lot when they first come in. We'll give you the benefit of the doubt, and you can have all this, but then if you can't follow that, and stay within those boundaries, we'll start taking it away.” (CO) |

| Adaptability | Adapting, changing or bending the rules to permit or support hospice activities; being “fair but firm” and retaining “the human part” of themselves in responding to issues; knowing when to insist on control vs. allowing some space for variation; balancing program needs against protocol, for example allowing movement between various areas of the prison; making exceptions when needed or reasonable; escorting inmates and families during off visit hours. | “These are sick people and these are people that are helping them and you have to work with that, you have to go a little further with them because you have to go that extra mile because they are sick...you have to be that interceptor sometimes, in between different areas and with their families...” (CO) |

| Patient safety | A sense of protection and responsibility for the vulnerable inmates; includes questioning or highlighting motives, for example making sure people have the “right” motives; maintaining unit structure, and working together to keep the vulnerable patients safe. | “Most of them are bedridden, so therefore, we have to provide security for them so nobody would go in and do anything to them because they can't defend themselves.” (CO) |

Security first

All participants acknowledged that the hospice program is first and foremost a prison hospice program; security, therefore, often superseded other concerns. We learned of several instances over the years where documented inmate infractions outside the program, as well as staff and COs perception of inappropriate behavior within the program (i.e. arguing with staff), led to volunteer suspension or dismissal from the program. Some volunteers expressed dissatisfaction that unit constraints sometimes limited the quality of care they provided (such as not being able to access certain foods for their patients or having COs unfamiliar with the program question their need to go to the medical unit at various hours) while they also described how security helped protect their patients from potential harm and maintained a space within which hospice can continue to function.

Boundaries not barriers

COs and staff described a problem-solving approach minimizing typical boundaries like protocol, procedures, and policies from becoming barriers to hospice function. For example, while regular prison policy frequently prohibits touch between inmates, in the hospice setting touch is an integral part of the day-to-day interaction between the volunteer inmate and the patient. COs and staff also cited the need to maintain professional boundaries while also treating others with respect and avoiding rigidity.

Adaptability

COs and staff described a willingness to examine, adapt, or change the rules to permit or support hospice activities whenever feasible and when not in direct conflict with security concerns. They also cited support from administration, for balancing program needs against protocol, such as allowing volunteer movement between various areas of the prison, and making exceptions when escorting inmates and families during off visit hours. While volunteers described a few instances where COs unfamiliar with the program made visiting patients outside regular hours difficult, these situations were largely resolved by staff and COs more familiar with the program, who strategically placed memos at gates where volunteers pass through.

Patient safety

COs and staff, like the inmate hospice volunteers, expressed a strong sense of protectiveness and responsibility for the vulnerable hospice patients. COs in particular saw their role in prison hospice as protecting inmates who may be at higher risk, and who require additional safeguarding because of their fragile condition. Members of all three groups mentioned how they monitored the unit and other providers (both staff and volunteers) to assure that people were operating with the “right” motivations, and that the hospice team had the resources and protection they needed to remain safe themselves and to ensure safety and comfort for vulnerable patients.

Shared Values

In addition to the more concrete practice and policy-driven elements, participants noted a sense of shared values essential to the daily functioning of the hospice program; these can be summarized by the general belief that all involved should do their best to uphold certain standards because this is “the right thing to do”. Table 4 presents a set of core values identified by COs, staff and volunteers: empathy and compassion, principled action, community responsibility, and respect.

Table 4.

Essential elements of prison hospice: Shared values

| Shared Values | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concepts in Context | Definition and Dimensions | Exemplary Quote |

| Empathy and compassion | Witnessing, experiencing and responding to the pain and suffering of others; the idea of putting oneself in others' shoes; a desire to help make things better. | “They're taken away from everything else... I always think about, would I want to be alone? Would I want to just be laying in poo or pee? No. They deserve the dignity. It doesn't matter that they killed somebody else to get here.” (Nurse) |

| Principled action | Doing the right things for the right reasons, having legitimate motivation for providing hospice care for all involved; authentic compassion and care for fellow prisoners; the desire to give back to the community; taking care of others as one would want to be cared for themselves. | “Whatever [the patient] need, you give it to him. And you don't ask for nothing in return. I mean, you don't do it for publicity or to be seen, but you do it because you love that man and you care about him.” (Volunteer) |

| Community responsibility | A sense of belonging to and participating in something bigger than any one individual or groups. Includes: stepping up and taking action; a willingness to be a leader and work through issues and problems; not abandoning worthy projects when things become complicated. | “Because we all work together and conquer the problem, they have something that needs to be done, we don't cry about it or... ‘You're supposed to do this, you're supposed to do that.’ We just get in and do it, it needs to be done it gets done.” (Volunteer) |

| Respect | Holding others in a positive regard that was both earned through trust and dependability. The idea that each role involved in the hospice program brings something unique and necessary to the daily delivery and management of the program; having respect for others performing their roles, and for those with whom they interact to make the hospice unit function. | “You have to give people the opportunity to demonstrate that they can be trusted. Proper training, the wardens, the support staff, letting us try different things...I think trust is a big part of it. Giving [volunteers] the opportunity to prove themselves, and to work with us.” (Nurse) |

Empathy and compassion

For volunteers, the ability to identify with patient suffering and needs meant that they could overcome their own discomforts or aversions to bodily functions, strong odors and intimate care, and express empathy and practice compassion, even when prison culture at large makes such action risky. COs and staff described how the humanizing influence of empathy and compassion helped them not only in relation to their own roles in relation to the prison hospice program but also made them better at their jobs overall. All noted a ripple effect whereby the growth of empathy and compassion has changed prison culture for the better, making their jobs easier.

Principled action

Inmates discussed how they had an ethical mandate to care for others as they would want to be cared for themselves at the end of their own lives. Neither personal gain nor positive recognition were legitimate reasons, and they contrasted voluntary end-of-life care with the motivations of others (staff) who receive pay for patient care, which was seen as a less “pure” motivation. Staff described “right reasons” as providing quality patient care in alignment with medical and nursing ethics, even when end-of-life care demands something extra beyond typical patient care. Lack of dignity and respect for dying inmates was seen by both COs and staff as particularly unethical and inhumane—adequate end-of-life care was not generally depicted as something special and dependent on being deserving, but as an opportunity to assert the value of all human life, regardless of history or circumstance.

Community responsibility

Staff and volunteers expressed a sense belonging to and participating in something bigger than any one individual or group. Most participants we interviewed, including COs, saw community responsibility as the necessity for “good people” to “step up” and take action. This was also seen as a willingness to take some leadership, shoulder the burden of working through issues and problems, and not abandoning worthy projects when things become challenging.

Respect

Respect was associated with a mutual positive regard that was earned through trust and dependability, but also with a general stance toward the inmates involved in the hospice program; that is, respect was given until or unless someone demonstrated behavior undeserving of respect, instead of withheld until someone is proven worthy of it. Participants expressed respect for others performing their roles well, and for the unique and necessary contribution of other groups to the daily delivery and management of the program.

Teamwork

Participants in all groups stressed the importance of individuals in different roles being willing to work together, collaborate and help achieve unit goals. Occasionally, breakdowns in teamwork or communication were mentioned; these examples were notable because they highlighted breaches in the normal flow of operations. Table 5 depicts three fundamental aspects of teamwork as described by participants across groups: an interdisciplinary (IDT) program model, recognition of stakeholder interdependence, and the fact that volunteers are formally organized as a team.

Table 5.

Essential elements of prison hospice: Teamwork

| Teamwork | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concepts in Context | Definition and Dimensions | Exemplary Quote |

| Interdisciplinary team (IDT) model | Application of an IDT model to end-of-life care in a correctional setting that involves the coordination of medical, volunteer and security roles working toward a common goal. IDT members include physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains working together in to deliver effective wrap-around services. COs may not be formal members of the IDT, but must be consulted and involved throughout the process. | “A lot of volunteers have kept the program going... And then nurses that have been here a while to kind of work with the new people and to give guidance as to what we used to do and what needs to be done and everything, but it's a team. Everybody's got their own part in it.” (Nurse) |

| Stakeholder interdependence | Recognizing the necessity of not just acting as a team, but of acknowledging the interdependent nature of providing hospice care. Teamwork in this sense also means working well together and a relationship of respect for other roles; knowing that one can rely and count on team members to be there, do their job, and cover for each other if needed. Instances identified as a lack of teamwork were infrequent and often due to a lack of understanding about program goals. | “The nurses...they show [volunteers] some of the things they can do to help them out like clean. Like the nurse is supposed to clean... sometimes we're so short of staff the hospice volunteers do that for them. And that stands out for them and the nurses praise them for helping them do their job too.” (CO) |

| Formal volunteer team | Volunteers exhibit a high degree of cooperation and coordination that is essential to the functioning of the program; they are formally organized and identify as a team. Volunteers hold regular team meetings with the hospice program coordinator to address program-related concerns (i.e. fundraising, items or resources for hospice rooms and patients) and to discuss their concerns about patient care. Communication amongst volunteers off the unit ensures that patient care duties and vigil shifts are covered. | “We [volunteers] communicate 24/7. We see each other in the dorms, in the education buildings...So every time we see each other, there's something needed, one will let somebody know. Somebody's not going to be able to make a vigil or visit: “Could you stand in?” “Yes, I'll stand in.” If I can't stand in, I'll find somebody that can stand in. And that's how we communicate.” (Volunteer) |

Interdisciplinary team (IDT) model

The effectiveness of an IDT model to end-of-life care entails various members of the team, including physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains, working together in a coordinated manner to promote optimal patient and family outcomes by providing warp-around services. Correctional health care is unique in that security must also be part of this approach. In LSP COs were not formal members of the IDT, but staff described (and we observed) numerous situations where they are integral to planning and implementing hospice services at multiple points in the process.

Stakeholder interdependence

COs described interdependence in terms of how they worked together with medical staff—and more indirectly the inmate volunteers—to incorporate patient and program needs with security procedures. Medical staff acknowledged how critical the volunteer role was to the functioning of the hospice program, and extending care beyond what the nurses alone would be able to manage. Volunteers described turning to hospice staff when they encounter something beyond the scope of their role, and expressed confidence that their concerns would be heard. Although infrequent, several inmate volunteers had negative experiences when COs unfamiliar with the hospice program or unclear about specific program goals prevented them from fulfilling their duties, but these were exceptions that underscored how daily management of the hospice program relied on the interdependence of multiple roles.

Formal volunteer team

COs, staff and inmate volunteers also stressed the high degree of cooperation and coordination amongst volunteers as essential to the functioning of the program (the organization of the LSP inmate volunteer program is described in greater detail below.) Volunteers are “officially” identified as a team members by a t-shirt that bears the logo “Hospice: Helping Others Share Their Pain Inside a Correctional Environment” which serves as a collective identity and recognition. Even while off the unit, many volunteers communicate closely to ensure that patient care duties and vigil shifts are covered.

Discussion

Earlier publications, including the handful of research studies cited above, provide critical insights for building the prison hospice evidence base. The National Prison Hospice Association (NPHA) has published personal and professional accounts of prison hospice development, and descriptions of several different models implemented in Connecticut, Texas, Illinois and Louisiana. In 1998 the NPHA drafted a set of prison operational guidelines outlining central concepts, policies and procedures for prison administrators and correctional health workers seeking to design and implement prison hospice.21

In 2009, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) published its Quality Guidelines for Hospice and End-of-Life Care in Correctional Settings.22 This document, created in collaboration with correctional experts, outlines ten key components of quality end of life care in correctional settings: inmate patient- and family-centered care; ethical behavior and inmate patient rights; clinical excellence and safety; inclusion and access; organizational excellence and accountability; workforce excellence; quality guidelines; compliance with laws and regulations; stewardship and accountability; and performance improvement. Within each of these areas the NHPCO sets forth specific guidelines for implementation and quality improvement and examples of how these can be met.

These recommendations and resources have been vital to raising awareness of the need for, and possibility of, more widespread implementation of prison end of life care. Yet there remains a relative lack of empirical research into the processes that shape the everyday interactions and practices necessary to sustain prison hospice programs. This may be at least partially responsible for the fact that, despite the availability of expert recommendations and resources, prison hospices have not proliferated more widely beyond the numbers previously reported by Hoffman and Dickson19 (69 prison hospices in the U.S.) and the NHPCO (“approximately” 75 in U.S. prisons and 6 in the Federal Bureau of Prisons.)36

Detailed knowledge concerning key operational elements and processes, based on the lived experience of multiple stakeholders, remains elusive. The steps necessary for translating global recommendations into specific program and policy implementation may still seem too daunting for correctional systems without this knowledge; administrators may remain unconvinced of the value of prison hospice without confirmation, via empirical qualitative and quantitative evidence, of how other systems have handled challenges and adaptations.

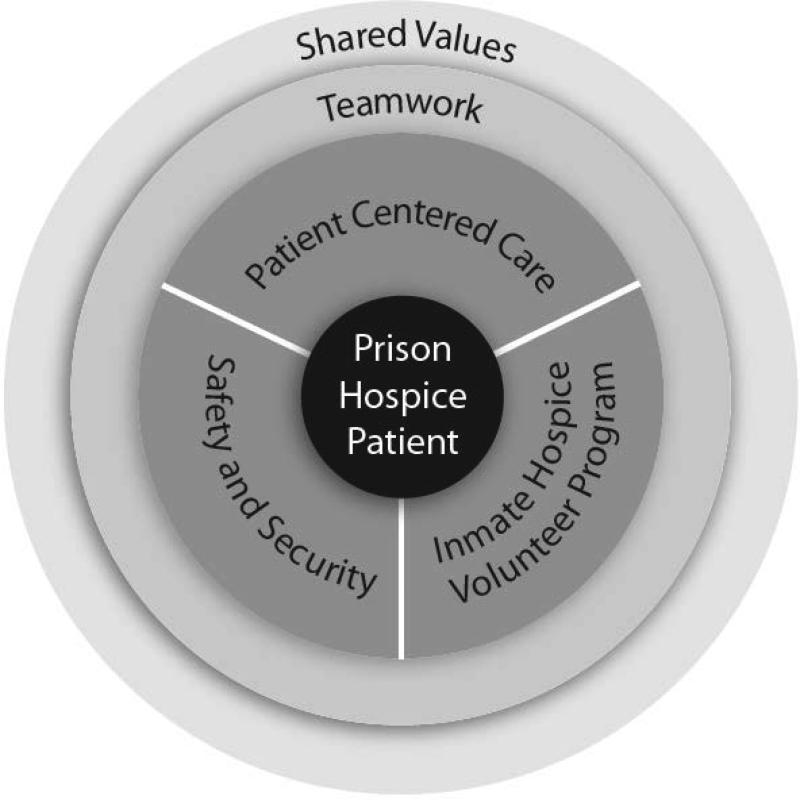

Figure 1 presents a working model of how the five essential elements inductively derived from our study data—patient centered care, the volunteer model, safety and security, shared values and teamwork—relate to each other and align with previously published recommendations, identifying the structural and cultural elements necessary to sustain a prison hospice program.

Figure 1.

Relationship of Essential Elements in Prison Hospice

This data-based model confirms and contextualizes several recommendations for specific policies and practices that experienced correctional health staff, COs, and inmate volunteers have endorsed as essential to maintaining a prison hospice program over time, including how more formal elements codified in policies and procedures shape, and are shaped by, culture and daily practice. This schema is not meant to replace those provided by national agencies or other researchers; rather, our findings confirm the importance of several key areas that emerged as central to sustainability in the model program we studied.

Structural Elements: Patient-Centered Care, the Volunteer Model, Safety and Security

Patient-centered care, the volunteer model, and safety and security represent core features of the prison hospice program that were developed at LSP through specific daily practices and supported by formal policies, training and procedures. A number of previous recommendations are reflected in our findings, including patient- and family-centered care, a formal IDT approach, inmate volunteer programs with training and support through ongoing meetings and supervision, a dedicated hospice coordinator, a volunteer coordinator (in the case of LSP, this is the same person as the hospice coordinator), a primary nursing model, and the provision of 24 hour presence and support at time of death through a hospice vigil. These are structural elements that provide a framework for the program and help maintain its stability. Of these, two stand out as notable because of how they contextualize prior recommendations.

A formal volunteer model

The LSP volunteer model emerged as perhaps the most significant structural element in our study. The ongoing existence of a formal volunteer program, through which inmate volunteers provide direct care to prison hospice patients, was cited by COs, staff and volunteers alike as the most important contributor to program effectiveness and sustainability.

Several specific features of how LSP has organized their volunteer program should be noted. Inmate volunteers, selected through a multi-level vetting process, receive both initial didactic and clinical training and ongoing education as a cohort, meeting regularly to identify program and cohort needs. LSP volunteers are organized as a prison club, which reinforces the collective and social nature of their work and affords them representation, visibility and legitimacy within the broader prison community. Through the facilitation of the LSP Hospice Coordinator and the Director of Nursing, they are also closely involved with decision-making and fund-raising for the program; this fosters a strong sense of personal and collective investment and stewardship toward the program. This higher degree of trust, responsibility and autonomy extends to informal mentorship that occurs between more and less experienced volunteers, a dynamic that is encouraged by both interactions with staff and the structure of the program.

Inmate volunteers are also entrusted with the provision of direct patient care, comparable to the role of a nurse aide, with the exception of taking vital signs or monitoring blood sugars. Patient care occurs via a primary care model where volunteers are matched with patients based on personality, history or compatibility of interests; volunteers then provide 1:1 care for their patients for the remainder of their hospice stay. Finally, as recommended by the NPHA and the NHPCO, volunteers provide 24 hour care and companionship for patients in the final 72 hours of life. This process, known as sitting vigil, is of extremely high significance and value to volunteers, staff and COs alike who see vigil as a direct reflection of the program mission and their collective professionalism and humanity.

Hospice education for COs

This structural element, identified as critical in earlier recommendations, appeared to be less central to the daily function of the LSP program. First, the need for hospice-specific training for COs has been identified as a critical need in supporting prison hospice. Despite this, COs in our study did not report receiving special training related to end of life care or hospice. In fact, several COs expressed how, if they are doing their jobs appropriately and well, they do not need special training because they are not delivering patient care but maintaining security and safety for all, including vulnerable hospice patients.

At the same time, all of the COs we interviewed also described how they learned about hospice and end of life issues by being in proximity to the program and watching the inmate volunteers and nurses provide patient care. They reported that working in and around the program substantially increased their awareness and understanding of end-of-life care issues and the goals of hospice, knowledge they took with them into their “free-world” lives. In fact, the one officer who expressed skepticism about the program in terms of inmates being kept alive, or getting undeserved better care than free-world patients, worked in a position at the farthest physical remove from the program. Several (including this participant) also said that COs who are not able to adapt to working around the program are weeded out and reassigned.

Our findings suggest that within this program, the influence of shared cultural values (such as religious and familial orientation) may reinforce the hospice mission despite lack of formal hospice training or education for COs. Receipt of specialized training may be seen as changing the CO role in ways that alter the meaning of this identity within a correctional context. Following this, efforts to educate COs regarding hospice need to address this potential conflict; efforts should also be made to educate COs outside the program who have no opportunities to experience hospice first-hand.

Cultural Elements: Shared Values, Teamwork

Shared values and teamwork represent more informal, less programmatic but nonetheless central elements that support the daily management and long-term operation of prison hospice. These elements represent cultural values that have emerged as COs, hospice staff and inmate volunteers have worked together to implement the hospice program over years.

Formal IDT and the value of teamwork

The concept of teamwork emerged in our analysis as more of a shared cultural value than a formal structural element; it appears that teamwork as a value may exert a more powerful cultural influence than teamwork as a programmatic feature. We observed at least two scheduled IDT meetings involving the LSP hospice coordinator, social worker, chaplain, and medical director (inmate volunteers were not included in IDT meetings.) These meetings were brief, and largely focused on patient requests for medication changes, arrangements for family visits and pastoral care. Far more prominent and productive seemed to be the teamwork occurring in routine interactions between hospice medical staff, COs and volunteers “on the fly” as they worked together to deal with the everyday complications of managing various aspects of the program.

The relationship between IDT as a structure and teamwork as a value seemed similar to the relationship between formal and experiential CO hospice training noted above—that is, there is a sense in which formalized or mandated policy may actually conflict with a sense of “doing” prison hospice because it is part of one's job and (as so many participants said) “the right thing to do”—not something exceptional that redefines one's fundamental role within the culture of the institution. This suggests that any additional training that COs and staff receive regarding hospice should not ignore extant concepts and values of cultural, ethical and moral responsibility which may already be working within a given system, as a way of naturalizing what may at first seem additional or exceptional.

Of course our data does not inform either a casual or temporal interpretation of the relationship between having a formal IDT which includes COs, and the development of a shared cultural value of teamwork. It is conceivable that implementing an IDT model could eventually ingrain a team approach among stakeholders with differing perspectives and interests. On the other hand, if teamwork is already part of the culture, then implementation of an IDT model may be more easily accomplished and more likely to persist. Prison hospice recommendations could therefore be enhanced with a focus on team-building beyond the IDT, perhaps utilizing case-based scenarios or simulations to emphasize cooperative problem solving in ways that acknowledge and value the unique and necessary roles of COs, health staff and volunteers and allow participants to retain their distinct cultural identities. These may be more effective if developed with direct input from (or even by) COs, medical staff, inmate volunteers and patients themselves.

The unique cultural elements at work in the LSP program may include beliefs and values that represent specific local, historical or geographic influences that may not easily translate to other diverse prison communities. It is conceivable, however, that each correctional institution interested in developing a hospice program can work with their own COs, correctional health care staff and inmates to identify those values which are central to their own culture and community, and integrate these into a formal rationale and plan for providing effective and sustainable end-of-life care. Once these shared values are identified, or emerge, targeted efforts can be made to promote them as cultural norms that represent everyone's best interests.

In summary, our findings correspond with several principal components of prison hospice programs identified in previous research and suggest that with key structures and supports in place, including ongoing examination and improvement of these structures, the delivery of effective and sustainable prison hospice and end-of-life care is possible at relatively low cost. This raises the possibility that other prison health care initiatives such as providing adequate care and protection of aging and disabled prison inmates might spark a similar sense of stakeholder buy-in and common mission.

To gain more traction, recommendations will likely require the support of confirmatory empirical data that also address the social and cultural adaptations and processes noted in previous studies29-33 and our work,33-34 because these insights arise over time, unfolding through daily practice. Cultural change is not mandated, but grows within the intra- and interpersonal dynamics of everyday experience, something we have tried to capture here. Prison hospice is more than a program, set of policies or mandate from administration; our participants told us that prison hospice exists in and through the daily practices and interactions of the men and women working to enact these principles. More research is needed to track the development and adaptation of prison hospice programs over time

Limitations

While comprehensive and based on multiple data sources, this study is essentially a case study of one prison hospice program. We have provided our justification for focusing on this program because of its history, national recognition and long-term sustainability. A systematic and objective comparison of a variety of prison hospice programs, including varied approaches to organization and provision of services, would greatly enhance our understanding of factors that contribute to the effectiveness and sustainability of prison hospice programs; such a study should also address important geographical, logistic, economic, and ideological differences. Finally, the assessment presented here is generally a positive one. Participants certainly described challenges to implementing and maintaining the prison hospice program through the years—as one inmate volunteer said, “It hasn't been all peaches and cream.” Nonetheless, the accounts of COs, treatment center staff and inmate volunteers, and our observations, consistently pointed toward many more examples of “what makes this work.”

Conclusion

To discern and compare the essential elements for sustaining prison hospice, we examined one exemplar program, the Louisiana State Penitentiary Prison Hospice Program at Angola. Our qualitative analysis revealed five essential elements—patient-centered care, the volunteer model, safety and security, shared values, and teamwork—that developed and matured at LSP over time. These essential components represent an investment by all parties—volunteers, COs, and medical staff—in program quality, maintained through formal program structures as well as shared values. While each corrections setting has its own culture and history, we maintain that these program components can be translated into other prisons to achieve similar outcomes and address the end-of-life care needs of aging and chronically ill prisoners.

Acknowledgment of Funding

This study was funded by a University of Utah Center on Aging Faculty Pilot Grant (Cloyes, PI) and a University of Utah College of Nursing Faculty Research Grant (Cloyes, PI).

Contributor Information

Kristin G. Cloyes, University of Utah.

Susan J. Rosenkranz, Oregon Health & Science University.

Patricia H. Berry, Oregon Health & Science University.

Katherine P. Supiano, University of Utah.

Meghan Routt, University of Utah.

Kathleen Shannon-Dorcy, University of Washington Tacoma.

Sarah M. Llanque, University of Utah.

References

- 1.Carson EA, Sabol WJ. Prisoners in 2011. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin (NCJ 239808) 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Human Rights Watch [September 15, 2014];Old behind bars: The aging prison population in the United States. http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/repotrs/usprisons01 12webcover_0.pdf.

- 3.Chiu T. It's about time: Aging prisoners, increasing costs , and geriatric release. Vera Institute of Justice; New York: [September 15, 2014]. http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/Its-about-time-aging-prisoners-increasing-costs-and-geriatric-release.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maruschak LM, Beavers R. Bureau of Justice Statistics HIV in prisons , 2007-08. Aids. 2009. 14:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidem Comm Health. 2009;63(11):912–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhlmann R, Ruddell R. Elderly jail inmates: Problems, prevalence and public health. Cal J Health Prom. 2009;3(2):49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeb S, AbuDagga A. Health-related research on older inmates: An integrative review. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:556–565. doi: 10.1002/nur.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rikard RV, Rosenberg E. Aging Inmates: A Convergence of Trends in the American Criminal Justice System. J Corr Health Care. 2007;13:150–162. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathew P, Elting L, Cooksley C, Owen S, Lin J. Cancer in an incarcerated population. Cancer. 2005;104(10):2197–204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aday RH, Krabill JJ. Special Needs Offenders in Correctional Institutions. Sage; Los Angeles: 2013. 2013. Older and geriatric offenders: Critical issues for the 21st century. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Sudore RL, Strupp HM, Willmott DJ, Walter LC. Being old and doing time: Functional impairment and adverse experiences of geriatric female prisoners. J Am Geriat Soc. 2006;54(4):702–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arndt S, Turvey CL, Flaum M. Older offenders, substance abuse, and treatment. Am J Geriat Psych. 2002;10(6):733–739. 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (NCJ 213600) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.AUTHOR

- 15.Fazel S, McMillan J, O'Donnell I. Dementia in prison: Ethical and legal implications. J Med Ethic. 2002;28:156–159. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.3.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AUTHOR

- 17.Mara CM. Expansion of long-term care in the prison system: an aging inmate population poses policy and programmatic questions. J Aging Soc Pol. 2002;14(2):43–61. doi: 10.1300/J031v14n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, Lawrence F. Comparing incarcerated and community-dwelling older men's health. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(2):234–49. doi: 10.1177/0193945907302981. discussion 250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman HC, Dickinson GE. Characteristics of prison hospice programs in the United States. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(4):245–52. doi: 10.1177/1049909110381884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AUTHOR

- 21. [January 29, 2015];National Prison Hospice Association. Prison Hospice Operational Guidelines. 1998 http://prisonhospice.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/prison-hospice-guidelines-revised3.doc.

- 22.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [January 29, 2015];Quality Guidelines for Hospice and End of-Life Care in Correctional Settings. 2009 http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Access/Corrections/CorrectionsQualityGuidel ines.pdf.

- 23.Evans C, Herzog R, Tillman T. The Louisiana State Penitentiary: Angola prison hospice. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(4):553–558. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tillman T. Hospice in prison The Louisiana State Penitentiary hospice program. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(4):513–524. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith S. A security officer's view of the Louisiana State Penitentiary hospice program. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(4):527–528. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West J. Room number six. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(4):525–526. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Head B. The transforming power of prison hospice: Changing the culture of incarceration one life at a time. J Hos Palliat Nurs. 2005;7(6):354–359. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osofsky MJ, Zimbardo PG, Cain B. Revolutionizing prison hospice: The interdisciplinary approach of the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Corrections Compendium. 2004;29(4):5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yampolskaya S, Winston N. Hospice care in prison: General principles and outcomes. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2003;20:290–296. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright K, Bronstein L. An organizational analysis of prison hospice. Prison J. 2007;87(4):391–407. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loeb SJ, Hollenbeak CS, Penrod J, Smith CA, Kitt-Lewis E, Crouse SB. Care and companionship in isolating environments: Inmates attending to dying peers. J Foren Nurs. 2013;9(1):35–44. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0b013e31827a585c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penrod J, Loeb SJ, Smith CA. Administrators' perspectives on changing practice in end-of-life care in a state prison system. Pub Health Nurs. 2014;32(2):99–108. doi: 10.1111/phn.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loeb SJ, Penrod J, McGhan G, Kitt-Lewis E, Hollenbeak CS. Who wants to die in here? Perspectives of prisoners with chronic conditions. J Hospice Palliat Nurs. 2014;16(3):173–181. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AUTHOR

- 34.AUTHOR

- 35.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [January 26, 2015];End of life care in corrections: The facts. http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Access/Corrections/Corrections_The_Facts.pdf.