Abstract

Blustein mapped career decision making onto Maslow’s model of motivation and personality and concluded that most models of career development assume opportunities and decision-making latitude that do not exist for many individuals from low income or otherwise disadvantaged backgrounds. Consequently, Blustein argued that these models may be of limited utility for such individuals. Blustein challenged researchers to reevaluate current career development approaches, particularly those assuming a static world of work, from a perspective allowing for changing circumstances and recognizing career choice can be limited by access to opportunities, personal obligations, and social barriers. This article represents an exploratory effort to determine if the theory of work adjustment (TWA) might meaningfully be used to describe the work experiences of Latino immigrant workers, a group living with severe constraints and having very limited employment opportunities. It is argued that there is significant conceptual convergence between Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and the work reinforcers of TWA. The results of an exploratory, qualitative study with a sample of 10 Latino immigrants are also presented. These immigrants participated in key informant interviews concerning their work experiences both in the United States and in their home countries. The findings support Blustein’s contention that such workers will be most focused on basic survival needs and suggest that TWA reinforcers are descriptive of important aspects of how Latino immigrant workers conceptualize their jobs.

Keywords: latino immigrants, person–environment fit, Maslow, psychology of work, qualitative, vocational psychology, theory of work adjustment

Introduction

The roots of the field of career development stretch back to Frank Parson’s pioneering interventions with poor immigrant workers (Blustein, McWhirter, & Perry, 2005; O’Brien, 2001). In subsequent decades, vocational psychology moved out of immigrant slums and into college counseling centers, but its focus did not shift entirely from the plight of immigrants. For example, in How to Counsel Students, Williamson (1939) detailed strategies to facilitate success of children of immigrant families attending colleges and universities. In the decades of plenty following the Second World War, working-class individuals found secure, good paying jobs with relative ease. The great challenge then faced by career counselors was successfully assimilating a deluge of new students into institutes of higher education. The flood of veterans taking advantage of G. I. Bill benefits was soon followed by the demographic bulge of the “Baby Boom.” Civil rights advances then opened the doors of higher education to yet more students.

The dominant career development approaches in this era of unprecedented economic growth, in which many individuals worked decades, if not entire careers for the same employer, were person–environment (P-E) fit models. Application of these models involved a number of assumptions: good career choices could be made by matching individuals and jobs on the basis of abilities, interests, and values; allowing for differences in abilities, career choice took place on a relatively level playing field, the world of work would remain relatively stable; and the growing economy would continue to allow for steady advancement. Consequently, career interventions focused almost entirely on making a good initial career choice because once launched, career trajectories could be expected to follow predictable courses. The economic changes of recent decades (e.g., corporate mergers, downsizing, globalization, and outsourcing) have greatly challenged such happy assumptions.

The Psychology of Work (PW)

Drawing upon the breadth of social sciences research and thinking about work, Blustein (2006) synthesized a perspective on career development he termed the psychology of work (PW). In contrast to models that assume a stable world of work, PW recognizes that career development occurs neither in a vacuum nor in a static work environment. PW conceptualizes both career choice and the resulting working life as occurring within a complex network of influences. In addition to interests, values, and abilities, work choices are impacted by factors such as personal and family obligations, financial means, social status, experiences of discrimination, economic climate, and government policies.

Blustein (2006) identified three core functions that work has the potential to fulfill: (a) work as a means for survival and power, (b) work as a means of social connection, and (c) work as a means of self-determination. Bluestein mapped career development onto Maslow’s (1970) model of motivation and personality and concluded that many career development models, particularly P-E fit models, tend to focus on higher level needs (self-determination) rather than the more basic needs (survival and power) most salient to many working-class individuals. By assuming career opportunities and decision-making latitude that may not exist for individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, these models are rendered less relevant to them. Although it may represent a distant goal, it is fairly meaningless for an individual with few marketable job skills and a family to support to know that a career requiring a college education would likely be very satisfying—should the individual somehow gain the means to obtain one.

It is important to recognize that PW does not call for the abandonment of previous models of career development (Blustein, 2006). Rather, Blustein called for a reevaluation of these approaches from a perspective that allows for continually changing circumstances for both the external realities impacting work and the internal perceptions individuals have of their opportunities, obligations, and barriers related to career development.

Latino Immigrant Workers

There are currently 42 million people of Latino descent living in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005, 2006). Approximately half of these Latinos are foreign-born. It is estimated that 9.6 million of these Latino immigrants are undocumented (Passel & Cohn, 2009). Being an undocumented immigrant can have a significant impact on the type of work one does. Hudson (2007) found evidence that citizenship status may account for more variance in predicting an individual’s occupation than either race or social class. Because undocumented immigrants have a very restricted range of employment alternatives, they are willing to accept poorer, and often more dangerous, working conditions than native-born workers (Orrenius & Zavodny, 2009). Consequently, researchers have found that foreign-born Latinos working in the United States have significantly higher rates of work-related injury and mortalities than native-born Latinos or non-Latinos (Loh & Richardson, 2004; Richardson, Ruser, & Suarez, 2003). Dong and Platner (2004) found that within the construction industry, Latino immigrant workers were fatally injured at two to three times the rate of native-born workers doing the same jobs.

In the spirit of PW, this article represents an exploratory effort to determine if the theory of work adjustment (TWA) is robust enough to meaningfully describe the work experiences of Latino immigrant workers, a group living with severe social constraints, having very limited employment opportunities and who are underrepresented in the career development literature.

Three Theories and Three Approaches

The three theories informing this manuscript (PW, Maslow, and TWA) have very different etiologies and philosophical underpinnings. Maslow’s (1970) model of motivation and personality arose out of his efforts to better understand and characterize the qualities of individuals who struck him as being remarkable human beings. Maslow accomplished this through conducting case studies of living individuals and by researching the lives of noteworthy historical figures. Although, this theory is built primarily upon subjective interpretations and qualitative data, its intent is to identify causal patterns and important structural elements that will generalize to the broader population. TWA (Dawis & Lofquist, 1984) arose from the “trait and factor” tradition in vocational psychology and is clearly grounded in logical positivism. Framed within an individual differences perspective, TWA assumes that vocationally relevant aspects of both individuals and work environments are stable enough to be measured and static enough to allow meaningful comparisons. In contrast, PW (Blustein, 2006), with an emphasis on individual perceptions and multiple, changing perspectives of the world of work, grew from a post-structuralist orientation, primarily as manifested by application of social cognitive theory to career development. However, as pointed out by Gelso and Lent (2000), such approaches are better viewed as complementing rather than competing with more structural approaches such as P-E fit models. The convergence between these three models, found by this study, argues for the wisdom of this suggestion.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and the TWA

As was previously discussed, Blustein (2006) mapped career development models onto Maslow’s (1970) model of motivation and personality and concluded that most models disproportionately focused on satisfying higher level needs. Therefore, as a first step in exploring the application of the TWA with Latino immigrant workers, its most salient constructs (reinforcer dimensions) were similarly mapped onto Maslow’s model.

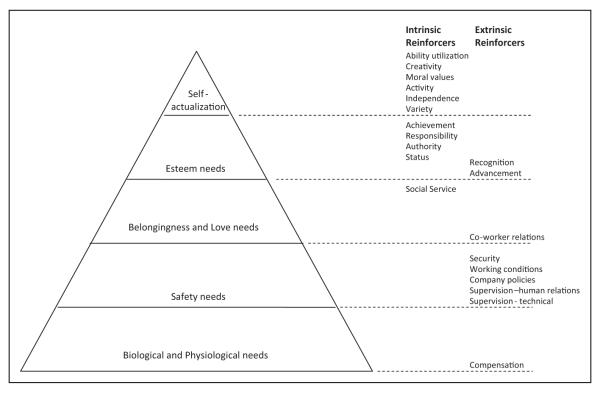

The most familiar summation of Maslow’s (1970) model of motivation and personality is the schematic representation of his hierarchy of needs (see Figure 1). Maslow postulated five levels of human needs that motivate behavior: (a) physiological needs (e.g., food, water, and sleep), (b) safety needs (e.g., physical security and a predictable environment), (c) belongingness and love needs (e.g., meaningful relationships with family and friends), (d) esteem needs (e.g., self-esteem and esteem of others), and (e) self-actualization needs (e.g., maximizing one’s potentials, self-acceptance, acting spontaneously, being creative).

Figure 1.

The relationship between Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and the TWA reinforcers.

TWA (Dawis & Lofquist, 1984) views work as an interactive and reciprocal process between the individual and the work environment. In simplest terms, individuals may be viewed as fulfilling the labor requirements of the work environment, in exchange for which the work environment provides reinforcers that satisfy a wide range of financial, social, and psychological needs for the individual. TWA has identified 20 work-related reinforcers that are available to varying degrees across nearly all workplaces (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Needs, Values, and Reinforcer Class in the Theory of Work Adjustment

| Need | Value | Reinforcer Class |

|---|---|---|

| Ability utilization | Achievement | Internal |

| Achievement | ||

| Creativity | Autonomy | |

| Responsibility | ||

| Advancement | ||

| Recognition | Status | |

| Authority | ||

| Status | ||

| Coworker relations | Altruism | Social |

| Social service | ||

| Moral values | ||

| Activity | Comfort | External |

| Independence | ||

| Variety | ||

| Compensation | ||

| Security | ||

| Working conditions | ||

| Company policies | Safety | |

| Supervision—human relations | ||

| Supervision—technical |

Based upon structural analyses, a number of groupings of the TWA reinforcers have been proposed (see Table 1). The 20 reinforcers may be grouped into six value dimensions (achievement, comfort, status, altruism, safety, and autonomy; Dawis & Lofquist, 1984). These value dimensions may be grouped into three broad reinforcer categories (internal, social, and external; Dawis, Dohm, Lofquist, Chartrand, & Due, 1987; Shubsachs, Rounds, Dawis, & Loquist, 1978) . By considering the source of reinforcers for each of these categories (self, others, and the work environment), one begins to see parallels with Maslow’s hierarchy in which physiological and safety needs are environmentally based, belongingness and love needs are met through interactions with others, and esteem and self-actualization needs are met within one’s self. It should also be noted that these three categories parallel Blustein’s (2006) three core functions of work as a means for survival and power, social connection, and self-determination.

Echoing this emphasis on the source of need satisfaction, the TWA reinforcers have also been classified as being related to either the intrinsic or extrinsic components of job satisfaction (see Figure 1; Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, 1967). Intrinsic job satisfaction refers to those aspects of the job that are inherent to the nature of the work being performed and that are primarily experienced internally by the worker (e.g., sense of challenge, sense of achievement, and level of independence). Extrinsic job satisfaction refers to those aspects of the job that are not inherent to the nature of the work and that are primarily under the control of one’s employer (e.g., compensation, job security, and working conditions).

Figure 1 represents an effort to “map” the TWA reinforcers onto appropriate levels of Maslow’s hierarchy. No lengthy, “formal” definitions exist for the 20 TWA reinforcer dimensions. For example, in the Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss et al., 1967), the meaning of each dimension is illustrated by the label given to it and an accompanying short statement. These statements are drawn directly from the 20 items of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ)—short form. The MSQ–long form contains a total of 100 items (5 per reinforcer dimension). The authors of the MSQ selected the 20 items from the long form (1 for each dimension) that had the most desirable psychometric properties to use in the MSQ–short form. Consequently, it was decided prior to the mapping effort to be guided primarily by the 20 items of the MSQ–short form. The remaining 4 items per reinforcer dimension contained in the long form were used to validate and/or provide nuance to interpretations. The “definitions” of the levels in Maslow’s hierarchy were derived both from Maslow’s (1970) own writings and discussion of the model in Liebert and Spiegler (1982).

The “mapping” process was planned in two phases. In the first phase, the authors independently assigned TWA reinforcer dimensions to levels of Maslow’s hierarchy. In the second phase, the authors met to compare their respective assignments of TWA reinforcers to levels of Maslow’s hierarchy and to resolve any differences. During the second phase, it was discovered that 19 of 20 reinforcer dimensions had been assigned to the same levels of the hierarchy. Only one, compensation, required discussion. The “definitional” item from the MSQ–short form referred to “My pay and the amount that I do” suggesting issues of basic fairness. However, two of the items from the MSQ–long form referred to pay in relationship to “friends” and that of “other workers” suggesting issues of status and belongingness. After discussion, it was decided that compensation might best be treated as the means by which one obtained basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing and therefore was assigned to the base of the hierarchy.

Convergence of the Models

Examination of Figure 1 reveals several patterns. The first is that the TWA reinforcers are distributed across all five levels of Maslow’s hierarchy. Admittedly, the distribution is somewhat skewed toward the higher level needs of self-actualization and esteem, but it is far from an exclusive focus on these two levels. As might be expected from the previous discussion, biological needs have the least coverage by TWA. Indeed, this level is only addressed to the extent that one accepts the argument that the money (compensation) one receives for working can be translated fairly directly into the purchase of basic life needs. However, the next level, safety needs, is well represented by five TWA reinforcers.

The second pattern evident in Figure 1 is that the three broad TWA reinforcer categories (internal, social, and external), despite their conceptual congruence with Maslow’s model, do not map as neatly onto Maslow’s hierarch as might be desired. At Maslow’s level of self-actualization, one finds a mixture of TWA reinforcers spanning all three categories. However, in the remainder of the model, the general arrangement is as expected with internal reinforcers being clustered higher on the model, social reinforcers near the middle, and external reinforcers at the lower levels. Overall, this suggests a reasonably good fit between the models.

The third pattern evident in Figure 1 is the fairly clear separation of the TWA intrinsic and extrinsic reinforcers on the hierarchy. The higher levels are addressed by intrinsic reinforcers and the lowest levels by extrinsic reinforcers. Overall, the model categorizing the TWA reinforcers as intrinsic or extrinsic appears to be a better match than the three category model. One possible explanation for this difference in fit may be found in the etiology of the two TWA models. The three category model grew out of work characterizing occupations and the work environment (Dawis et al., 1987; Shubsachs, et al., 1978). The extrinsic/intrinsic model grew out of work characterizing individual job satisfaction (Weiss et al., 1967). If one allows that Maslow’s model reflects general well-being and recognizes the robust relationships that have been found between job satisfaction and general well-being (Walsh & Eggerth, 2005), it makes sense that the extrinsic/intrinsic model should be a somewhat better fit.

In any event, it is our argument that taken together, the convergence between Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and TWA suggests that TWA has cleared at least one hurdle related to Blustein’s (2006) challenge to reevaluate existing career development models. However, one is still left with the need to determine if in practical terms, these reinforcer dimensions have relevance and meaning among a group as socially and economically marginalized as Latino immigrant workers. The remainder of this article explores this concern by presenting the findings of a qualitative study in which Latino immigrants were interviewed and asked to discuss their jobs.

Method

This study used individual key informant interviews with 10 Latino immigrant workers to explore their work experiences both in the United States and in their countries of origin.

Participants

A total of 10 individual interviews were completed for this study. Five interviews were conducted in Cincinnati, Ohio and five in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Four of the participants were female and six male. Their ages ranged from 19 to 41. Their educational levels ranged from no formal education to college, with 7 of 10 participants having less than a high school education. All currently worked in low-wage/low-skill jobs in construction, manufacturing, or the service sector. This represented a narrower range of work settings than in their countries of origin. The length of time in the United States ranged from 2 to 10 years, with half having lived in the United States from 3 to 5 years. For ethical reasons related to the protection of the participants (Eggerth & Flynn, 2010), no information was collected regarding documentation status. However, the agencies doing the recruiting understood that undocumented individuals were of particular interest to the researchers and offered assurances that they had recruited accordingly. (See Table 2 for detailed demographics.)

Table 2.

Participant Demographics

| Recruitment Site |

Age | Gender | Years in the United States |

National Origin |

Years of Formal Education |

Employment in Country of Origin |

Current Employment in the United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cincinnati | 25 | M | 3 | Mexico | 12 | Farmer | Manufacturing |

| 32 | F | 4 | Guatemala | 12 | Teacher | Manufacturing | |

| 37 | M | 5.5 | Peru | 16 | Painter | Manufacturing | |

| 21 | F | 2 | Guatemala | 0 | Domestic | Janitor | |

| 19 | M | 4 | Guatemala | 6 | Farmer | Meat packing | |

| Santa Fe | 40 | M | 2 | Mexico | 8 | Varied | Security guard |

| 36 | F | 5 | Guatemala | 8 | Manufacturing | Various service jobs |

|

| 27 | M | 3 | Mexico | 6 | Meat packing | Construction | |

| 21 | M | 8 | Mexico | 8 | None | Construction | |

| 41 | F | 10 | Mexico | 6 | Domestic | Fast food |

The participants for this study were a convenience sample recruited from a group of individuals who had previously agreed to participate in a focus group for a larger study of the occupational safety and health experiences of Latino immigrants working in the United States. The interviews were conducted in Cincinnati, Ohio and Santa Fe, New Mexico. The participants were recruited by representatives of local advocacy groups serving their respective Latino immigrant communities. The interviews were conducted in facilities provided by the advocacy group, typically the offices used by the advocacy groups. As such, the facilities were both familiar to and convenient for the participants. All participants were 18 or older, immigrants from Latin America, and currently employed in the United States.

Procedures

Prior to convening the focus group for which the participant was originally recruited, if sufficient numbers would remain for a viable focus group, one participant was selected at random and asked to instead take part in an individual interview in which they would be asked to discuss their work experiences both in the United States and in their countries of origin. The interview was of approximately the same duration (slightly over 1 hr) as the focus group for which the participant had originally been recruited. The participant received the same compensation ($50) for the interview that they would have for the focus group. All participants so approached agreed to be interviewed individually. The interviews were all conducted in Spanish by the same individual, who was fluently bilingual in English and Spanish. Although this interviewer was not Latino himself, he had over a decade of professional experience working with poorly educated, low-income Latinos, both in Latin America and in the United States. Audio recordings were made of the interviews for latter transcription. Upon completion of transcription and translation into English, the recordings were destroyed to ensure the confidentiality of the research participants.

Interview Protocol

The interview protocol contained three broad categories of questions. In the first, participants were asked to discuss their favorite job since coming to the United States. In the second category, participants were asked to discuss the job they liked the least since coming to the United States and to describe their efforts, if any, to improve circumstances on that job. In the third category, participants were asked to contrast differences between working in the United States and in their countries of origin. (See Appendix A for the full interview protocol.)

Data Analysis

For the purposes of this study, a structured approach to content coding was used. In contrast to an “open coding” or grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) in which researchers code responses using the themes and patterns that emerge solely from their reading of the transcripts, a structured approach attempts to fit participant responses into preexisting categories. In this case, the categories were defined by the TWA reinforcer dimensions.

As was discussed earlier, no “formal” definitions exist for the TWA reinforcers. Therefore, coding of interview items was guided in a manner similar to that used to “map” the TWA reinforcer dimensions onto Maslow’s hierarchy. Primary weight was given to the 20 items of the MSQ–short form, which had been selected from the larger pool of 100 items used by the MSQ–long form, having been identified by the instrument authors as having superior psychometric properties (Weiss et al., 1967). The remaining 80 items of the MSQ–long form were used to provide additional definitional depth and/or nuance on an “as needed” basis.

The transcripts (in both Spanish and English) were reviewed independently by two researchers and coded for statements reflecting the TWA reinforcers. The two sets of coding were then compared, differences identified and discussed until resolved and a final consolidated coding of the transcripts was produced.

Results

Review of the interview transcripts revealed that 17 of 20 TWA reinforcers were referred to over the course of the 10 interviews. These 17 reinforcers covered the entire range of six higher level TWA work value dimensions. The three reinforcers that were not referred to by the participants were moral values, supervision—technical, and creativity. The TWA reinforcers compensation and security were alluded to in each interview. In the following, for the sake of brevity, representative quotes will be reproduced for each of the six work value dimensions rather than all 17 of the reinforcers referred to by the participants.

Achievement

The TWA achievement value is associated with the reinforcers ability utilization and achievement. These reinforcers are associated with the satisfaction one receives from doing work one does well, successfully rising to a challenge at work, and/or from feeling that one’s work is meaningful. Given that many undocumented Latino immigrants have jobs that are poorly paid, physically demanding and in unpleasant, if not dangerous, work environments, one might not expect much satisfaction in anything other than the accomplishment of reaching yet another payday. However, this is not the case. For example, women from traditional backgrounds, some of whom have never worked outside of the home, express satisfaction in finding work (typically in the service industries) that they are familiar with. A representative statement is

Yes, yes I like this job (cleaning houses) also because, well, fortunately it is something that I know how to do. (Female, age 41, Santa Fe)

A number of immigrants expressed satisfaction with being able to learn new things or being able to successfully meet work challenges. Representative statements include:

I learn a lot about math here. Yes, because they give us different amounts and we have to convert them to feet and inches. In Guatemala we don’t use feet we use meters but here everything is in feet and inches. (Female, age 32, Cincinnati)

and

Participant: I attend to the clients. I do everything, sometimes I have to clean, sometimes I have to be in the kitchen, sometimes I’m at the register and sometimes I have to give the people their food. My job is to do everything, to be where I am needed.

Interviewer: Do you like to be doing everything or would you prefer to do only one?

Participant: I like things the way they are because I feel useful and I feel challenged. It feels good to know that I can do everything that needs to be done there. (Female, age 36, Santa Fe)

However, it is important to note that for most immigrants, the ultimate value of doing one’s work well and of rising to challenges at work is how directly these translate into increased job security, employability, and/or income.

Autonomy

The TWA autonomy value is associated with the reinforcers creativity and responsibility. These reinforcers are associated with the satisfaction one receives from being able to use one’s own judgment to direct one’s work activities and of being able to develop innovative approaches to work tasks. As was indicated earlier, creativity was not alluded to in these interviews. The low complexity level and rote nature of many of the jobs held by Latino immigrants may leave little room (or incentive) for innovation. All of participant statements that could be associated with the autonomy value were in reference to responsibility. Paralleling findings related to the achievement value, autonomy was less valued as an end itself, but as a means to an end—in this case, escaping the pressure to work faster and harder. A representative statement is

I am happy with him (the boss). He doesn’t walk around telling you to hurry up or to do this or that. He just gives you the address, tells you what you’ll need … I can just call him on the phone and he brings me more materials, everything I need. Sometimes I don’t even see him, I only see him when he gives me the checks to hand out. (Male, age 21, Santa Fe)

Status

The TWA status value is associated with the reinforcers advancement, recognition, authority, and social status. These reinforcers are associated with the satisfaction one receives from having opportunities to move into better job positions at work, being praised for doing good work, directing the work activities of others, and being respected within one’s community for the work one does. There were frequent references to reinforcers associated with the status value. As might be expected from the discussion of other reinforcers, these reinforcers were linked by the immigrant workers to both job security and employability. The majority of references were related to opportunities for advancement and recognition for a job well done, both of which were viewed by participants as a fairly direct route to higher pay. One important theme that emerged in connection with discussion of status reinforcers was the ambivalence that seems to characterize the lives of many undocumented immigrant workers. Any apparent blessing is examined closely for possible downsides—in particular, decreased job security or pressure to increase productivity to unsustainable levels. Another important theme to note is that in many instances, references related to the status value were characterized as much by the absence of reinforcers as by their presence. Representative statements included:

No one knew how to weld aluminum and they began to tell us we could make more money if we learned. So I decided I’d give it a try. So I would practice and practice … My idea is that you have to learn as much as you can in the company. Your job will not be there forever so if you learn it will be easier to get a job in other companies. (Male, age 25, Cincinnati)

All the employees are from a staffing agency and everyone is paid the same. There’s no difference between the person folding, the person punching and those welding and in most places welders are always paid more. So I would tell them … look you could pay the workers doing more difficult work more. You could give them a little more money and they would feel better and would be happier with their jobs. (Male, age 25, Cincinnati)

Well it’s a big decision because of the commitments one has (as a supervisor), and there are more responsibilities, because if something goes wrong they will blame you … It’s not so much that I am going to feel better than the others but rather the simple fact that the people are valuing my work and what I do. (Female, age 32, Cincinnati)

and

Interviewer: Why do you like your job (as foreman)?

Participant): Well, no one is around to pressure me, no one says ‘Hey, do this!’ no one yells at me … because I’m in charge, the foreman as they say, that’s why.” (Male, age 21, Santa Fe)

Altruism

The TWA altruism value is associated with the reinforcers coworker relations, social service, and moral values. These reinforcers are associated with the satisfaction one receives from having cordial relations with one’s coworkers, feeling that one’s job somehow contributes to the greater good and be able to perform one’s job without violating one’s values. As indicated earlier, no identifiable references were made to the reinforcer moral values. Most references to this category were to coworker relations. The importance of coworker relations is not surprising for Latino immigrant workers. Many immigrants find jobs through social networks within the immigrant community. Given both the expense of automobile ownership and the difficulty undocumented immigrants have obtaining a valid driver’s license, many rely upon others for rides to and from work. The consequences of bad relations with coworkers can threaten both current and future employment in ways such as not being informed about job opportunities and/or being unable to find reliable transportation to the worksite. In some instances, coworkers are from the same extended family group and/or the same small community in Latin America. Consequently, a falling out on the job between two coworkers has the potential to cause a “ripple effect” impacting family and friends thousands of miles away. Given the multiple levels of connections between many Latino immigrant coworkers, it is not surprising that many of the references to the altruism value were tinged with the ambivalence discussed previously. Representative statements included:

They wanted to put me as the head of a group, but I didn’t want problems … It’s not that I didn’t want the promotion it’s that I didn’t want problems with the other workers … I had seen that others who were put in charge didn’t even last three months before getting fired and I wanted to keep my job … Workers would always take things out of the trash, which was prohibited, and this would create problems for the group leader (because you are held responsible for your workers) … They don’t even give you much of a raise, maybe 20 or 30 cents … It’s not worth it. (Female, age 31, Cincinnati)

There are things I like, for example, there are some very friendly people. I’ll tell you something, the people from the U.S. are very good people … So what I enjoy most about my work is attending to the clients. I feel good because I practice my English and chit chat with them. I have made many friends this way. (Male, age 36, Santa Fe)

and

I would prefer to manage other people because I like to teach. I have always been like this because everything I have learned I have wanted to share. I have taught a lot of people. There are those who are selfish and don’t share what they know. Not me. (Female, age 31, Cincinnati)

Comfort

The TWA comfort value is associated with the reinforcers activity, independence, variety, compensation, security, and working conditions. These reinforcers are associated with the satisfaction one receives from having something to do most of the day, opportunities to work alone, opportunities to do different job tasks from time to time, being paid well for the work one does, having stable, steady employment, and having a physically comfortable workplace. Although all of the reinforcers were touched upon, compensation and security were mentioned most frequently. For Latino immigrants, compensation has an importance that is hard for nonimmigrants to fully comprehend. Most immigrants working as day laborers have been cheated out of some or all of their pay on at least one occasion. Some employers attempt to avoid legal responsibility for employing undocumented immigrants by hiring through subcontractors and/or staffing agencies. Immigrants who have been in such employment situations report instances of financial exploitation ranging from having unreasonable amounts deducted for services such as use of the agency shuttle to commute to and from work, to not being paid at all. When complaints are lodged with the staffing agency, the contracting company is blamed, and when complaints are made at the worksite, the staffing agency is blamed—resulting in circular finger pointing and no redress for the exploited immigrants. When an immigrant is paid, there are often multiple claimants for the money. In addition to local living expenses and trying to save for the future, most are expected to send money to family members back home and some remain in ongoing debt to the human smugglers who arranged their border crossings. Representative statements included:

When you are in a job the most important thing is going to be your pay. It’s always that way because that’s why we came here. (Male, age 25, Cincinnati)

I have to tell you I didn’t like it because it was, I don’t know, like boring. Always doing the same thing, it was not interesting. In the beginning I learned how to do it but then I didn’t learn anything else. Where I am now, I’ve been here 5 years and I’m still learning. There are always two or three difficult things that I had never done and I learn to do them. (Female, age 21, Santa Fe)

I had the opportunity to work full time for the union, but they told me that I would be on provisional status for two months (before becoming a full employee). But, I couldn’t leave my current job because the work with the union was not a sure thing. (Female, age 32, Cincinnati)

It’s very hot there (where she works), we asked them to put in air conditioning—we have heat. They said they would think about it and they did but it didn’t help much. They only put in one fan that made as much noise as an airplane but at least they put that in. We have to yell during the summer. When winter comes we’ll be okay because we won’t have this discomfort. (Female, age 32, Cincinnati)

Safety

The TWA safety value is associated with the reinforcers company policies, supervision—human relations, and supervision—technical. These reinforcers are associated with the satisfaction one receives from being employed in a setting where company policies are clearly stated and fairly enforced, having a supervisor who is respectful and responsive to worker needs, and having a supervisor who is technically competent and is able to teach subordinates how to do their jobs. As indicated earlier, no identifiable references were made to the reinforcer supervision—technical. The lack of supervisory expertize and/or training of workers likely has a number of sources. One is the language barrier existing between most Latino immigrants and their supervisors, particularly in areas of the United States that have not traditionally been settlement areas for Latinos. Another factor may be the relatively low-skill level of many of the jobs in which Latinos are employed leads employers to believe little or no technical expertize and/or training of workers is necessary. Unfortunately, the significant occupational health disparities that exist between Latino immigrant workers and American-born workers suggest that at the very least, Latino workers could benefit from adequate safety training. Although financial necessity often forces Latino immigrant workers to accept poor treatment from their employers, they are very aware that they are being treated unfairly. Representative statements included:

What I don’t like is that sometimes they tell us that they aren’t going to pay overtime. That’s what I don’t like. (Male, age 19, Cincinnati)

For me a good job, above all else, there would be respect. That the supervisor respects the worker and the worker respects the supervisor. Without respect you can’t do anything. (Male, age 37, Cincinnati)

I changed companies because my old boss had a lot of problems, he always scolded us, he would always yell. He treated us badly. He yelled at us a lot. (Female, age 27, Santa Fe)

The most important thing for me is to be at peace with the boss and my co-workers. It’s not that I want to make less money but if I was in a situation where the boss would pay less but would treat me well, treat me like a human well then I’d be okay earning less. (Male, age 40, Santa Fe)

Discussion

Over the course of the 10 interviews, 17 of 20 TWA reinforcers, representing all six of the TWA work value areas were mentioned by the Latino immigrant workers. These reinforcers covered all levels of Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs. Although not reflected in the relative number of quotations included in this article, the two reinforcers most frequently mentioned during the interviews were compensation and security. This is clearly consistent with Blustein’s (2006) predictions that individuals in low-wage/low-skill jobs would be most concerned with the satisfaction of needs lower on Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy. However, it is significant that these workers were clearly aware of aspects of employment other than a paycheck and job security. Even under circumstances of constrained choice, some participants reported making employment decisions based upon the satisfaction of higher level needs such as enjoying a variety of work tasks, experiencing a sense of accomplishment, having positive interactions with others, and seeking opportunities for self-improvement—sometimes at the expense of lower level needs such as higher compensation and greater job security. Although these workers held jobs often considered undesirable by most Americans, they were all able to find positive meanings in their jobs—if only from the pride of having done one’s work well.

A number of the quotes reflect ambivalence when referring to some reinforcers. Others reflect guardedness toward authority. One might be tempted to find in these statements support for the proposed Latino cultural traits of fatalism and deference to authority (Antshel, 2002; Cuellar, Arnold, & Gonzalez, 1995). However, it is our belief that although these traits may color the manner in which these topics are presented, overall it is more likely that these statements are an accurate reflection of how vulnerable to exploitation undocumented workers realize themselves to be.

Congruent with Blustein’s (2006) observations, references to a number of the TWA reinforcers were made within the context of commenting upon their absence. Because many career development professionals work with individuals having more life options than the immigrant workers interviewed for this study, the tendency in the literature has been to conceptualize reinforcers as being defined by their presence—not their absence.

As has been previously mentioned, 3 of the 20 TWA reinforcers (creativity, moral values, and supervision—technical) were not clearly referred to during any of the interviews. Given that both creativity and moral values map onto self-actualization, the highest level of Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy, and the participants all held low-wage/low-skill jobs, one might not be surprised that no clear mention, positive or negative, was made of these two TWA reinforcers. However, that begs the question why references were made to other reinforces that map onto self-actualization in Maslow’s hierarchy.

The nature of the data collection opportunity did not allow us to conduct follow-up interviews with any of the study participants. However, discussions with representatives of the “grassroots” community organizations that we had partnered with on this data collection effort shed some light on the issue. For most of these immigrant workers, creativity has never been expected nor asked for on the job. Even in instances allowing for innovation, immigrants are wary of sharing anything with employers that might serve as a tool to extract even more work from them. It is far more likely that an employer would use a “labor saving” innovation to increase production than to reduce the job demands of the immigrant workers.

Our community partners felt that the failure to reference moral values might simply reflect the reality of the immigrant work experience. The TWA instruments define this reinforcer with terms such as being able to “do work without feeling it is morally wrong” and “being able to do things that don’t go against my religious beliefs” (Dawis & Lofquist, 1984). Most immigrants are never in the sort of work situations that offer moral challenges. As one community partner suggested, “There isn’t a lot of opportunity to violate your moral principles lifting a shovel or swinging a hammer.”

The omission of references to supervision—technical may also be explained as reflecting the reality of the immigrant work experience. The TWA instruments define this reinforcer in terms of how well one is trained to do one’s job and how much you can rely upon a supervisor for guidance. Given the language barriers between Latino immigrants and their employers, and the nature of the jobs, most are never formally trained by their employers. Many immigrant workers report that they learn to do their jobs through trial and error or are taught by other immigrants who have been employed in the same workplace longer. Even if these workers receive “training” from their employers, it tends to be wholly inadequate. In the pilot project for another study, the authors of this article asked a sample of Latino immigrant workers if they had been trained on how to perform their jobs safely. Many said that they had. When asked about the specific nature of the training, it often consisted of a supervisor pointing to a piece of equipment and merely saying, “Careful around that. It’s dangerous!” or “That’s sharp. Don’t cut yourself!”

Saturation

It is possible that the omission of the three TWA reinforcers is simply the result of the modest sample size of this study. Sample sizes for qualitative research cannot be calculated using the sort of power analyses used for quantitative research approaches. Rather the concept of saturation is used to determine whether or not an adequate number of interviews have been conducted (Kuzel, 1999). Saturation is considered to have occurred when no significant new topics are generated by interviews. It is possible that constraints of working with a convenience sample left this study several participants short of achieving full saturation.

A number of factors do point toward having reached an acceptable level of saturation. The authors’ previous experience working with this population investigating similar topics found that saturation was often reached after as few as 6–7 interviews. Therefore, 10 interviews could be expected to yield a fairly comprehensive range of responses. Of the 17 TWA reinforcers identified by the coders, only 1 (achievement) was mentioned by a single participant. The remaining 16 reinforcers were clearly referenced by multiple participants. In addition, despite the “missing” three reinforcers, the six higher-order work values of TWA were all well represented by the participant responses. The pattern of the reinforcers mentioned was consistent with expectations based upon Blustein (2006). Finally, plausible explanations for the missing reinforcers were provided by representatives of the advocacy groups that served as the study’s cultural consultants.

Practical Implications

Although Latino immigrant workers face significant challenges related to well-being and adjustment at work, it is unlikely that they will ever seek counseling in traditional career guidance settings. Differences of language, culture, and documentation status only begin to describe the chasm that exists between the day-to-day lives of the typical individual seeking career guidance and the lives of these Latino workers. Although this article argues for the applicability of TWA to describing important aspects of the work experiences of Latino immigrants, it is only a first step in addressing the concerns raised by Blustein (2006). Many of the barriers limiting their employment opportunities are institutional and societal—well beyond the powers of these immigrants to change on an individual level.

In the face of such obstacles, it might seem that career development professionals have little to offer these immigrants. However, Frank Parsons worked with individuals facing similar challenges and found enough success to lay the foundations of the career guidance movement. An important element of Parsons’ success was that he worked in and with the immigrant community. Although the days of settlement houses are long over, one can identify “grassroots” advocacy groups serving the Latino immigrant community. Any of these groups are acutely aware of the challenges these immigrants face on the job. Clearly, offering Latino immigrant workers, the same menu of services provided to students in college guidance centers would not be useful. Partnerships with community groups will play a crucial role in helping career development professionals to better understand the immigrant community and to develop ways to best meet their work-related needs. Barriers of language might necessitate that this assistance be channeled through one’s community partners. Examples include serving as an expert consultant for the agency and training bilingual agency staff to provide basic career guidance services.

The findings reported in this article suggest that Latino immigrants identify a range of work reinforcers very similar to those reported by native-born workers. However, it was clear that compensation and job security trumped all other concerns. Counselors will need to expand their conceptualization of “career” beyond those jobs requiring lengthy, specialized training. As Maslow (1970) argued, self-actualization must be put on hold until basic survival needs are satisfied. Consequently, one’s first goals will likely be related to ways work can be made safer, more stable, and, if possible, better paid. Career guidance professionals will need to familiarize themselves with the local job market, English as a second language programs, and any community agencies providing low or no cost legal or medical services. In addition, a basic understanding of state and federal laws concerning labor, workplace safety, and immigration would be helpful.

Once basic survival needs are ensured, many immigrants could still benefit from psychological services. The middle of Maslow’s (1970) pyramid holds needs associated with belongingness and love. Latino immigrants are likely to suffer from multiple stressors related to these needs. Most are separated from their families, they tend to be socially isolated within their host communities, some are culturally disorientated, undocumented status emphasizes a sense of “otherness,” and they live within an increasingly hostile political environment. It is beyond the scope of this article to delve further into these concerns. Hopefully, this list is compelling enough to encourage others to conduct research in this area.

Conclusion

This study suggests that an important convergence exists between the reinforcer dimensions of TWA and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In addition, the findings support Blustein’s (2006) argument that individuals with few job skills employed in low-wage jobs will be most concerned with meeting basic survival and safety needs. Rising to Blustein’s challenge, the TWA appears to do a fairly good job of capturing how Latino immigrant workers conceptualize the rewards available to them from work. The 10 interviews conducted in this study identified 17 of 20 TWA reinforcers. The reasons why three reinforcers did not emerge are not entirely clear. However, plausible explanations for their absence were offered by Latino cultural experts. Rather than being a failure to reach saturation, these findings could represent the realities of the immigrant work experience and/or genuine cultural differences in the conceptualization of work. It should also be noted that a somewhat different set of categories might have been decided upon if a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) had been used. In this approach, the researchers code responses using the themes and patterns that emerge solely from their reading of the transcripts rather than attempting to fit responses in preexisting categories as was done in this study.

Altogether, the results of this study do suggest that TWA might be fruitfully applied to Latino immigrants, individuals with very few degrees of freedom in their employment situations. However, this study is far from a full validation of the entire TWA model with this population. That is clearly beyond the scope of this exploratory study and awaits future research efforts.

Beyond any theoretical implications this work might have, the quotes contained in this article are a powerful reminder that beyond current headlines, the stakes for Latino immigrants are more immediate and higher than they are for any other group involved in the politics of immigration reform. If indeed, as opponents of immigration argue, “They are here to take our jobs!” it is sobering to consider that this study suggests that for Latino immigrants, the rewards of “taking our jobs” are defined as much by their absence as much as by their presence.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for the research and authorship of this article was provided by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Bios

Donald E. Eggerth received his doctorate in counseling psychology from the University of Minnesota. He is currently a Senior Team Coordinator in the Education and Information Division of NIOSH. In this position, he coordinates a multistudy research agenda concerning the work experiences of Latino immigrants. In addition, he is a Research Fellow with the Consortium for Multicultural Psychology Research at Michigan State University and an Affiliate Faculty member with the Department of Psychology at Colorado State University. In his spare time, he enjoys reading, attending the symphony, and traveling with his family.

Michael A. Flynn has a master’s degree in anthropology and is a Public Health Advisor with the Training Research and Evaluation Branch of NIOSH. His research focuses on developing and evaluating culturally tailored interventions as well as identifying pre- and posttraining conditions that facilitate or hinder occupational safety among immigrant workers. Prior to coming to NIOSH, he worked for 10 years in nongovernmental organizations in Guatemala, Mexico, Ohio, and California. In his spare time, he enjoys cycling, camping, and coaching his sons’ soccer teams.

Appendix A. Interview Script and Probes

- Tell me about the favorite job you have had since coming to the United States.

- Describe the job to me.

- What did you like about the job?

- Was there anything you did not like about the job?

- How long did you work there?

- Are you still working there?

- If not, what happened?

- Tell me about the least favorite job you have had since coming to the United States.

- Describe the job to me

- What did you dislike about the job?

- When did you begin to notice the things you did not like about the job?

- Did you immediately notice the problems or become aware of them over time?

- Did you notice the problems or were they brought to your attention by someone else? Who?

- Did it get better or worse over time?

- How did you react to the situation?

- What was your initial reaction?

- Did this change over time?

- Did you talk to anyone about the problem?

- Who did you talk to?

- What was their reaction?

- Did you ever contemplate quitting, going to the boss etc.?

- How was the situation resolved?

- Do you think you would react differently if it happened again?

- Was there anything you liked about the job?

- How long did you work there?

- Are you still working there?

- What are the differences between working in the United States and your home country?

- What do you like/dislike about working in the United States?

- What did you like/dislike about working in your home country?

- Do you react differently to problems at work here than you did at home?

- What are some concerns you have when you think about leaving a job?

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Antshel KM. Integrating culture as a means of improving treatment adherence in the Latino population. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2002;4:435–449. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein DL. The psychology of working: A new perspective for career development, counseling, and public policy. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein DL, McWhirter EH, Perry JC. An emancipatory communitarian approach to vocational development theory, research, and practice. The Counseling Psychologist. 2005;33:141–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, Gonzalez G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis RV, Dohm TE, Lofquist LH, Chartrand JM, Due AM. Minnesota occupational classification system III: A psychological taxonomy of work. Vocational Psychology Research, University of Minnesota; Minneapolis: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis RV, Lofquist LH. A psychological theory of work adjustment. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Platner JW. Occupational fatalities of Hispanic construction workers from 1992 to 2000. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2004;45:45–54. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggerth DE, Flynn MA. When the third world comes to the first: Ethical considerations when working with Hispanic immigrants. Ethics & Behavior. 2010;20:229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gelso CJ, Lent RW. Scientific training and scholarly productivity: The person, the training environment and their interaction. In: Brown SD, Lent RW, editors. Handbook of counseling psychology. 3rd ed Wiley; New York, NY: 2000. pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson K. The new labor market segmentation: Labor market dualism in the new economy. Social Science Research. 2007;36:286–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Liebert RM, Speigler MD. Personality: Strategies and issues. The Dorsey Press; Homewood, IL: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Loh K, Richardson S. Foreign-born workers: Trends in fatal occupational injuries, 1996–2001. Monthly Labor Review. 2004;127(6):42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. Rev. ed Harper and Row; New York, NY: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KM. The legacy of Parson: Career counselors and vocational psychologists as agents of change. Career Development Quarterly. 2001;50:66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius PM, Zavodny M. Do immigrants work in riskier jobs? Demography. 2009;46:535–551. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn VD. A portrait of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Pew Hispanic Center; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S, Ruser R, Suarez P. Contained in safety is seguridad. The National Academies; Washington, DC: 2003. Hispanic workers in the United States: An analysis of employment distributions, fatal occupational injuries, and non-fatal occupational injuries and illnesses; pp. 43–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shubsachs ABW, Rounds JB, Dawis RV, Lofquist LH. Perceptions of work reinforcer systems: Factor structure. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1978;13:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1990. Basics of qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau [Retrieved September 8, 2005];Facts of features: Hispanic heritage month 2005. 2005 from http://www.census.gov/

- U.S. Census Bureau [Retrieved January 8, 2008];Current population survey: Annual social and economic supplement. 2006 from http://www.census.gov/

- Walsh WB, Eggerth DE. Personality and vocational psychology: The relationship of the five factor model to job performance and job satisfaction. In: Walsh WB, Savickas ML, editors. Handbook of vocational psychology. 3rd ed Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW, Lofquist LH. Manual for the Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire. Minnesota studies in vocational rehabilitation: Vol. XXII. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson EG. How to counsel students. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1939. [Google Scholar]