Abstract

Background

Almost 800 000 teachers were working in Germany in the 2012–13 school year. A determination of the most common medical problems in this large occupational group serves as the basis for measures that help maintain teachers’ health and their ability to work in their profession.

Methods

We present our own research findings, a selective review of the literature, and data derived from the German statutory health insurance scheme concerning medical disability, long-term illness, and inability to work among teachers.

Results

Compared to the general population, teachers have a more healthful lifestyle and a lower frequency of cardiovascular risk factors (except hypertension). Like non-teachers, they commonly suffer from musculoskeletal and cardiovascular diseases. Mental and psychosomatic diseases are more common in teachers than in non-teachers, as are nonspecific complaints such as exhaustion, fatigue, headache, and tension. It is commonly said that 3–5% of teachers suffer from “burnout,” but reliable data on this topic are lacking, among other reasons because the term has no standard definition. The percentage of teachers on sick leave is generally lower than the overall percentage among statutory insurees; it is higher in the former East Germany than in the former West Germany. The number of teachers taking early retirement because of illness has steadily declined from over 60% in 2001 and currently stands at 19%, with an average age of 58 years, among tenured teachers taking early retirement. The main reasons for early retirement are mental and psychosomatic illnesses, which together account for 32–50% of cases.

Conclusion

Although German law mandates the medical care of persons in the teaching professions by occupational physicians, this requirement is implemented to varying extents in the different German federal states. Teachers need qualified, interdisciplinary occupational health care with the involvement of their treating physicians.

Teachers have essential duties concerning qualification and education. They also contribute to both the stability of society and the further development of future generations. Both numbers of teachers, who have a broadly comparable duty profile and qualification level, and their employment structure are relevant to medical care. In 2012, 2% of the working population in the EU (approximately 5 million people) were teachers (e1). In the 2012/13 school year there were 797 257 teachers in Germany. Of these, 498 273 worked full-time, 298 984 part-time, and 148 361 on an hourly basis in general and vocational schools. Women account for 58% of teachers who work full-time and 85% of those who work part-time (1). In Germany 76% of teachers are tenured; there are major differences between federal states in the former West and East Germanies in this respect (e2).

Everyday school life is very much shaped by developments in information technology, and also by the more and more multicultural nature of the social environment and increasing school autonomy. This means that more of teachers’ duties involve school management and administration (e1).

The traditional occupation of teaching has given way to a cultural, societal, and social occupation with bureaucratic duties (2). This is characterized by social and interactive emotional labor and is also associated with high demands and multiple stresses (3). The idealized figure of the teacher is associated with various roles as educator, partner, adviser, mediator, social worker, professional manager, and political thinker (4). Teachers’ health has a defining effect on quality of teaching and thereby on the success of students’ learning (5– 7, e3, e4). In particular, burnout among teachers reduces quality of teaching (6, 7).

The autonomy of Germany’s federal states makes it difficult to compile national illness-related statistics for teachers as a professional group: differences include variation between school systems and between numbers of tenured and salaried teachers. Additionally, there are data protection regulations and the various statistical compilation systems and professional classification systems used in social insurance systems. Internationally, not only established school systems but also health care structures and outcome parameters recorded are subject to differing conditions and requirements. These framework conditions also make it almost impossible to identify internationally comparable indicators to describe teachers’ health. A further difficulty faced by scientific studies is the large variety of procedures used to evaluate health risks and resources.

These results of a selective search of the literature and the evaluation of available statistics should provide information, for treating physicians in particular, concerning the classification of teachers’ health issues.

Stress in the teaching profession

The teaching profession includes the following stress factors:

Physical, including noise and indoor climate factors

Chemical, e.g. hazardous substances in specialized teaching and building materials

Ergonomic, such as computer workstations.

The stress factors cited by teachers themselves are time pressure, working hours, noise in school, excessively large class sizes, problems with school authorities, and lack of autonomy on the one hand; and inefficiency, students’ behavioral problems and lack of motivation, problem behavior on the part of parents, and low social status on the other (4, 8– 11, e3, e4). The dominating factor is psychoemotional stress (4, 10– 13).

When asked, teachers always rate stresses caused by school as high to very high. However, this should not only be interpreted as a risk to health. The following demands on teachers, in particular, can impact on health if they are not dealt with (4):

Complexity: nontransparent, unpredictable situations

Long periods of high concentration

Divided attention

Inadequate recovery during the teaching day

Situation-related change of behavior patterns in teaching

Different evaluation criteria used by students, parents, head of school, school authorities, and the public

Being a “lone voice” in the bureaucratic or other system

Intrusion of work into free time.

This negative viewpoint remains dominant if we examine how teachers cope with the demands they face and teachers’ health. In the future, the profession’s resources must be more integrated into job design and health promotion, as the question of how teachers are to remain healthy despite their high levels of work-related stress must be addressed.

Teachers’ health problems

The statements made on the subject of teachers’ health are dependent on which diagnostic tools are used and which threshold values are used to classify health issues (4, 11, 12). In addition, objective data in the form of clinical diagnoses is rarely obtained for this professional group; questionnaires and self-reporting on health are the norm. This is also true of international studies (e5– e21). There is considerable variation in figures on the frequency of subjective health problems in teachers. Schönwälder et al. (9) work on the premise that healthy teachers with few or no complaints are a minority in Germany. In Austria, 14% of teachers rate their health as excellent, and 37% as very good (e22). Seibt et al. (14) found no illness in 28% of teachers. According to Krause und Dorsemagen (15), at least 20% of teachers have severe health problems and therefore very limited work performance. However, screening examinations have shown that teachers differ from the general population in that they have less marked cardiovascular risk factors such as excess weight, metabolic disorders, and smoking, and behave more health-consciously, particularly regarding sport and physical activity (4, 11, 14, e23– e27) (Table 1).

Table 1. Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in teachers versus the general population (DEGS1).

| Parameter | Teachers sample | DEGS1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 2144) |

Male (n = 423) |

Female | Male | ||

| Blood pressure (mmHg)* (e23) | (ntotal = 7096) | ||||

| Systolic BP | Mean ± SD | 128.9 ± 18.4 | 133.1 ± 18.1 | 120.8 | 127.4 |

| Diastolic BP | Mean ± SD | 82.8 ± 11.0 | 86.0 ± 11.6 | 71.2 | 75.3 |

| Hypertension*(≥140/90 and/or use of antihypertensive medication) | % | 43.8 | 52.7 | 29.9 | 33.3 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) (e24) | (ntotal = 7116) | ||||

| BMI | Mean ± SD | 25.0 ± 4.3 | 26.2 ± 3.4 | 26.5 | 27.2 |

| - Underweight (<18.5) | % | 1.3 | 0 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| - Healthy weight (18.5 to 24.9) | % | 57.2 | 42.3 | 44.7 | 32.2 |

| - Overweight (25.0 to 29.9) | % | 28.6 | 45.2 | 53 | 67.1 |

| - Obese (≥30.0) | % | 12.9 | 12.5 | 23.9 | 23.3 |

| Lipid metabolism parameters (mmol/L) (e25) | (ntotal = 7045) | ||||

| Total cholesterol | Mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 5.9 ± 1.2 | 5.3 | 5.2 |

| - High (≥5.0) | % | 50.7 | 46.6 | 60.5 | 56.6 |

| HDL cholesterol | Mean ± SD | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| - Low (<1.0) | % | 1.1 | 7.2 | 3.6 | 19.3 |

| Exercise (e26) | (ntotal = 7741) | ||||

| Regular exercise | % | 73.2 | 75.3 | 65.6 | 67 |

| Smoking (e27) | (ntotal = 7899) | ||||

| Smokers | % | 12 | 16.2 | 26.9 | 32.6 |

Study period for teachers sample: 2004 to 2014 in Saxony (current data). 2008 to 2011 in Germany (DEGS1: Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults 2012 [e23–e27])

BP: blood pressure; BMI: body-mass index; DEGS1: German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults—first wave; HDL: high-density lipoprotein

*Teachers sample: 24 to 64 years; single blood pressure measurement; regular blood pressure medication

DEGS1: 18 to 79 years; mean of second and third blood pressure measurement; medication taken in the last seven days

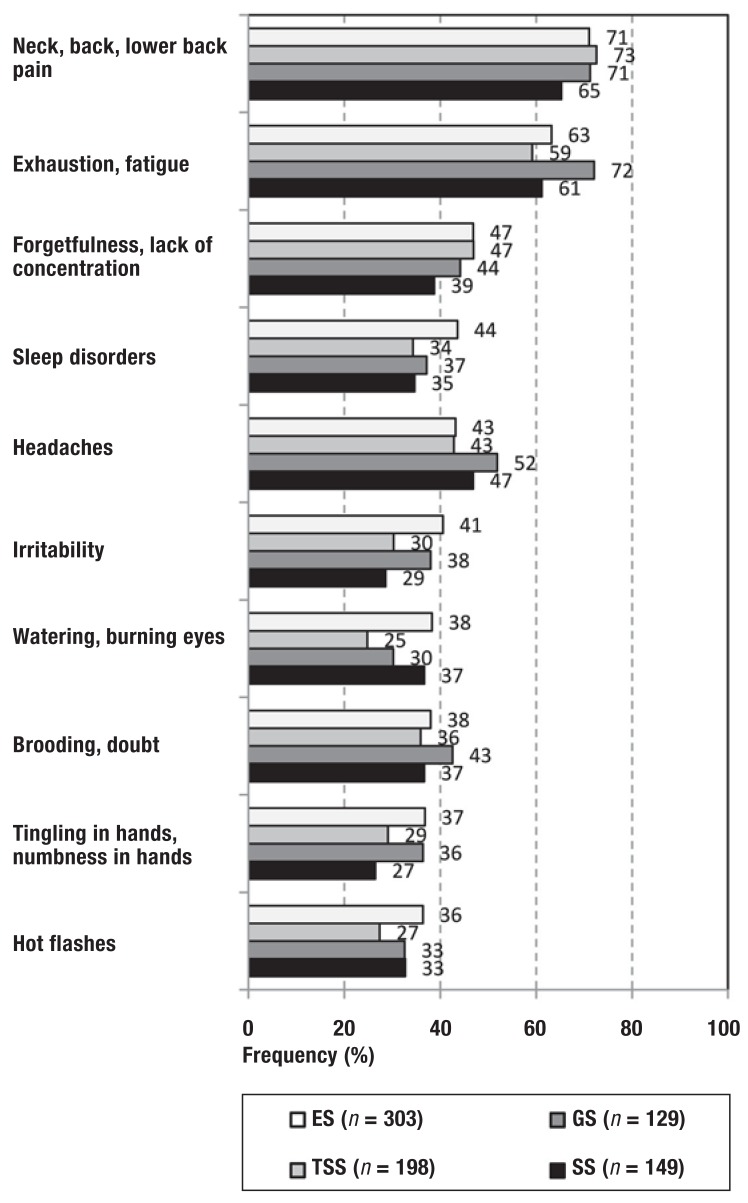

In multiple studies, regardless of the type of school, the dominant psychosomatic complaints are found to be exhaustion and fatigue, headaches, tension, listlessness, sleep and concentration disorders, inner restlessness, and increased irritability (4, 9, 10, 16, 17, e28) (Figure 1). These complaints are more common than in other working individuals in Germany (18).

Figure 1.

Most common complaints (e28) among teachers by type of school

(research performed in 2009; as stated by employees [ 14])

ES: elementary school; TSS: technical secondary school; GS: grammar school; SS: special school

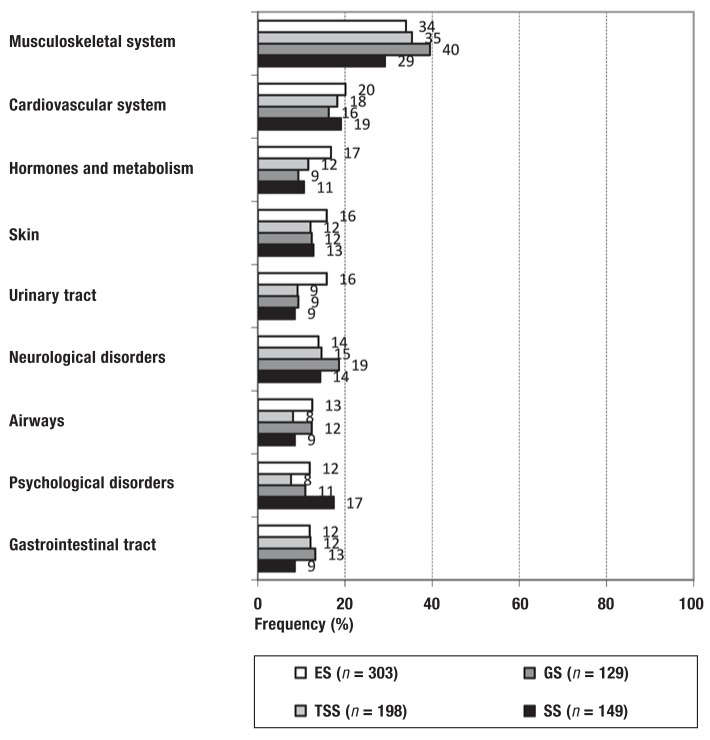

The most common self-reported diagnoses among teachers are disorders of the musculoskeletal system and the cardiovascular system (14, e29) (Figure 2). The underlying morbidity pattern has not changed substantially among this professional group in the last 25 years. For example, as early as 1988 disorders of the musculoskeletal system, cardiovascular system, and digestive system were the most common complaints among teachers (21 534 female, 4400 male) and in all working individuals in the former German Democratic Republic (162 041 women, 467 149 men) (19). However, teachers showed a higher frequency of disorders of the nervous system, particularly neuroses. These findings are based on the widest-ranging collection of data—even internationally—on clinical diagnoses in teachers and other professional groups (e30). Recent studies have confirmed a higher prevalence of psychological complaints than the population average (8, 14, 20).

Figure 2.

Medical diagnoses (e29) of teachers by type of school (research performed in 2009; as stated by employees [14])

ES: elementary school;

TSS: technical secondary school;

GS: grammar school;

SS: special school

Risk of burnout

To date, teachers are the homogenous group in which the risk of burnout has most frequently been investigated. According to the ICD classification, burnout is not a disease (21, 22). Dealing with burnout poses a medical and scientific dilemma. As yet it has no uniform definition, and there are a variety of different tools with which to measure it; these do not meet traditional criteria for good-quality testing (22, 23). This means that personal misconceptions concerning one’s own work can be interpreted as burnout (22). Subjective information on complaints of burnout is usually used uncritically even in scientific studies and clinical diagnostics.

However, the concept of burnout has taken root in clinical practice. According to figures that are representative of the population, more than 4% of the German population are diagnosed with burnout every year (12-month prevalence). Those employed in education are particularly likely to be affected (24). Because isolated symptoms are also often classified as burnout (14, 23), the findings available on the incidence of burnout among teachers are contradictory. Prevalence rates ranging from 1% to 33% have been reported (3, 12, 14, 23– 28, e10– e18). In the studies by Böckelmann et al. (29) and Seibt et al. (14), in contrast, complete burnout was found in only 1% to 5% of female teachers using the Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey (MBI-GS) (e31), although approximately half and one-third respectively reported some symptoms of burnout. In a study comparing professional groups (e32), female teachers had a lower rate of burnout (1%) than female doctors (5%). In Finland, according to the figures from a population-wide survey, 25% of the adult population suffer from mild symptoms of burnout, and 3% from serious symptoms (30). Further data from international studies is summarized in Table 2 (e11– e22, e31, e33– e40). This overview confirms that findings on teachers’ health vary. For example, following major education reforms in Hong Kong there was an increase in psychological problems and suicide rates among teachers (e19). The correlations illustrate the possible health effects of occupational demands that are difficult to cope with.

Table 2. International study findings on teachers’ health.

| Countr | Investigated variable(s). sample size n | Findings | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Stress (PAW); physical and psychological health (SF-36); sick leave (days); n = 1066 |

|

Bogaert et al. 2014 (e11) |

| Italy | Symptoms of depression (CES-D); symptoms of anxiety (SAS); n = 113 |

|

Borelli et al. 2014 (e12) |

| Korea | Burnout (MBI-ES); n = 499 |

|

Shin et al. 2013 (e17) |

| China (Hong Kong). UK |

Stress (PSS); physical and psychological health (SF-36); effort–reward imbalance (ERI-Q); n = 259 |

|

Tang et al. 2013 (e19) |

| Portugal | Burnout (MBI-GS); n = 281 |

|

Ferreira & Martinez 2012 (e13) |

| Spain | Burnout (MBI-GS); n = 727 |

|

Rey et al. 2012 (e16) |

| Austria | Symptom checklist (SCL-90); physical and psychological health (SF-36); n = 2498 |

|

Griebler 2011 (e22) |

| Namibia | Burnout (MBI-ES); n = 337 |

|

Louw et al. 2011 (e14) |

| USA | Burnout (MBI-ES); symptoms of depression (CES-D); n = 267 |

|

Steinhardt et al. 2011 (e18) |

| Romania | Burnout (MBI-GS); n = 177 |

|

Vladut & Kállay 2011 (e21) |

| Spain | Burnout (MBI-ES); n = 1386 |

|

Otero López et al. 2010 (e15) |

| EUROTEACH study | Burnout (MBI-GS); somatic complaints (SCL-90-R); n = 2796 |

|

Verhoeven et al. 2003 (e20) |

n: no. of study participants; CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff 1977 [e35]); ERI-Q: Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (Siegrist et al. 2004 [e39]);

MBI-ES: Maslach Burn-out Inventory—Educator Survey (Ruy et al. 2003 [e37]); MBI-GS: Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey (Schaufeli et al. 1996 [e31]); PAW: Psychosocial Aspects at Work Questionnaire (Symonds et al. 1996 [e33]); PSS: Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al. 1983 [e38]); SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (Zung 1971 [e36]); SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist (Derogatis 1977 [e40]); SF-36: Short-Form Health Survey (Ware et al. 1993 [e34])

27% of the teachers investigated by Böckelmann et al. (29) stated that they were suffering severe emotional exhaustion, the core component of burnout. High levels of emotional strain are also reported in approximately one-third of teachers in the German Teachers’ Health Handbook (Handbuch Lehrergesundheit) (31). According to the Stress Report for Germany (Stressreport Deutschland 2012) (32), 13% of men and 20% of women in the general population suffer physical and emotional exhaustion. In teaching and education, physical and emotional exhaustion is present in 22% of those in employment. This is the second-highest value for any field.

In addition to the MBI, standardized questionnaires such as the Work-Related Behavior and Experience Pattern (AVEM, Arbeitsbezogene Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster) (3) and the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) (26) are often also used to determine the risk of burnout in samples of teachers. Schaarschmidt (3) identifies an experience and behavior pattern associated with burnout in 25% of all teachers, and Bauer (33) in 30%. However, these behavior patterns are not a diagnosis of burnout; rather, they describe various patterns of increased-risk behavior.

According to Hillert et al. (34), a combination of the following criteria typically leads to symptoms of burnout:

Limited ability to distance oneself from one’s work

Strong tendency towards resignation in the face of failure

Limited ability to obtain social support (AVEM pattern B) (3).

Lehr (20) pleads for established diagnostic systems for depressive disorders to be used in research on teachers’ health. This would enable better comparison with other professional groups.

In one of the largest studies involving online questionnaires, Nübling et al. (26) used the COPSOQ and found slightly increased burnout scores among teachers in Baden–Württemberg than the mean for all occupations (46 versus 42 on a scale ranging from 0 to 100). The high job security of tenured teachers may have led to lower burnout scores. Among teachers in Rhineland–Palatinate, however, there was no difference in burnout scores between teachers and the overall COPSOQ population. For life and job satisfaction, teachers actually reported higher scores than other professional groups (e3).

The COPSOQ results of a Europe-wide study of teachers showed a gender effect in burnout (35). Female teachers had a mean score of 50, male teachers of 43. “Work–privacy conflicts,” job insecurity, and emotional demands were confirmed as negative job features.

In summary, there is no reliable data to date assessing the extent of burnout among teachers. This is also the conclusion drawn in the current expert opinion of the Action Committee on Education of the Bavarian Industry Association (VBW, Vereinigung der Bayerischen Wirtschaft e. V.) concerning psychological stress and burnout among personnel in the field of education (22). The German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics (DGPPN, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde) (36) believes there is an urgent need for precise epidemiological research on psychosocial problems at work and their consequences, and for improvements in how burnout as a concept is handled. The contradictory findings that have been obtained are not sufficient to characterize burnout as a typical “teachers’ illness” (14, 23). Nevertheless, burnout, particularly its exhaustion components, is a major aspect of teachers’ health problems.

Sick leave

Health insurers and federal states’ statistical offices provide occupation-specific information on sick leave. It should be noted that in statutory health insurers’ figures teachers are subsumed into various fields and economic groups, together with those employed in other occupations. In addition, no such data is available for teachers with private health insurance or tenured teachers. This makes it harder to classify and compare findings on numbers of teachers on sick leave.

However, collation of health insurers’ data (Table 3) reveals that salaried teachers with statutory health insurance tend to have fewer days’ sick leave than the mean for individuals insured with the same health insurers (37– 39). In 2012 and 2013 the professional groups that included teachers had fewer days’ sick leave than the health care professions. Illnesses in fields that included teachers were also of shorter duration than in the comparator groups. Rates of diseases of the airways and psychological disorders are higher than the mean for individuals insured with the same health insurers, while rates of cardiovascular, muscular, and skeletal diseases and injuries are lower (37). Since the introduction of the additional diagnosis Z73 in 2004 as part of ICD-10, which also includes burnout as a diagnosis, the number of days of sick leave associated with Z73 had increased tenfold for the population as a whole by 2013 (37). In 2013 the proportion of these cases of sick leave was approximately three times higher for those working in education and insured with AOK than the mean for the field. This reflects the fact that burnout is diagnosed more frequently in professions with a social component than in other professional groups.

Table 3. Sick leave among teachers in Germany.

| Sick leave _(days’ leave × 100/insurance days) | Cases of sick leave _per 100 members*1 | Mean duration of cases of sick leave (d) | Days’ sick leave _per 100 members*1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOK insurants 2013 (37) | ||||

| –Total | 5.1% | 160.7 | 11.5 | 1850 |

| AOK insurants 2013: field: education and teaching | ||||

| –Total for field | 4.5% | 191.2 | 8.5 | 1625 |

| –West | 4.4% | 192.8 | 8.3 | 1600 |

| –East | 4.9% | 184.5 | 9.7 | 1790 |

| AOK insurants 2013: economic group: health and social care | ||||

| –Total | 5.3% | 163.5 | 12.2 | 1992 |

| AOK insurants 2012 (37) | ||||

| –Total | 4.9% | 153.3 | 11.8 | 1812 |

| AOK insurants 2012: field: education and teaching | ||||

| –Total for field | 5.0% | 242.4 | 7.6 | 1842 |

| –West | 4.8% | 238.6 | 7.4 | 1766 |

| –East | 5.8% | 256 | 8.3 | 2125 |

| AOK insurants 2012: economic group: health and social care | ||||

| –Total | 5.1% | 155.2 | 12.5 | 1934 |

| DAK insurants 2013 (38) | ||||

| –Total | 4.0% | 121.1 | 12 | 1456 |

| DAK insurants 2013: economic group: education. culture. and media | ||||

| –Total for economic group | 3.1% | 106.4 | 10.6 | 1124 |

| DAK insurants 2013: economic group: health care | ||||

| –Total for economic group | 4.6% | 126.4 | 13.2 | 1663 |

| DAK insurants 2012 (38) | ||||

| –Total | 3.8% | 112 | 12.6 | 1405 |

| DAK insurants 2012: economic group: education. culture. and media | ||||

| –Total for economic group | 3.0% | 99.5 | 11.1 | 1108 |

| DAK insurants 2012: economic group: health care | ||||

| –Total for economic group | 4.4% | 117.1 | 13.9 | 1626 |

| TKK insurants 2013 (39) | ||||

| –Total | 4.0% | 115 | 12.8 | 1470 |

| TKK insurants 2013: professional field: social and educational occupations. pastoral care providers | ||||

| –Total for field | 3.9% | 115 | 12.4 | 1430 |

| –Male | 3.1% | 91 | 12.4 | 1130 |

| –Female | 4.9% | 143 | 12.4 | 1780 |

| TKK insurants 2013: professional field: health care professions | ||||

| –Total for field | 4.1% | 109 | 13.7 | 1490 |

| –Male | 3.9% | 98 | 14.5 | 1420 |

| –Female | 4.3% | 121 | 13 | 1570 |

| TKK insurants 2012 (39) | ||||

| –Total | 3.9% | 106 | 13.4 | 1420 |

| TKK insurants 2012: professional field: social and educational occupations. pastoral care providers | ||||

| –Total for field | 3.8% | 107 | 12.9 | 1380 |

| –Male | 3.0% | 84 | 13 | 1090 |

| –Female | 4.7% | 134 | 12.8 | 1720 |

| TKK insurants 2012: professional field: health care professions | ||||

| –Total for field | 4.0% | 100 | 14.7 | 1470 |

| –Male | 3.9% | 92 | 15.3 | 1410 |

| –Female | 4.2% | 111 | 13.9 | 1540 |

*1Insured year-round

Gender-specific data on sick leave of teachers insured with AOK shows higher figures for women than for men; duration for the two genders is comparable (37). More days’ sick leave are reported in the federal states of the former East Germany than those of the former West Germany, both overall and in professional groups that include teachers (37). The figures for 2013 were lowest in Bavaria, at 3.5%, and highest in Berlin, at 6.5%. In the former West German states the mean percentage of individuals taking sick leave is 4.4%; the corresponding figure for the former East German states is 4.9%.

In summary, teachers take fewer days’ sick leave than the mean for individuals insured with the same health insurers or the health care professions investigated. It is not known whether some days on which teachers were unfit for work fell on school holidays and therefore were not recorded, or whether presenteeism was part of the reason for their low number of days’ sick leave.

Long-term diseases

The percentage of teachers with long-term diseases in general schools in Germany was 4.0% in 2012 and 3.8% in 2013. Female teachers (2013: 4.0%) suffer from long-term diseases more frequently than male teachers (2013: 3.3%). Here too we find the same difference between East and West in terms of days’ sick leave: in 2013 the percentage of teachers with long-term diseases was 5.3% in the former East Germany and 3.0% in the former West Germany (e41).

Figures on the number of cases of sick leave due to long-term diseases per 100 members show that psychological disorders are the most common. Between 2011 and 2013, the number of cases per 100 members rose from 1.6 to 1.8.

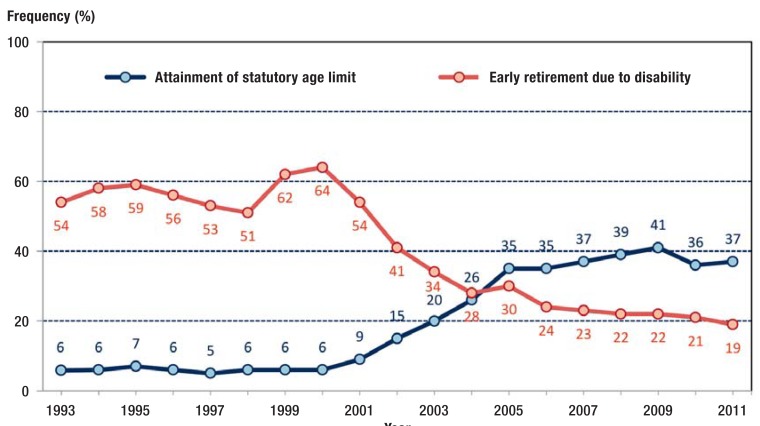

Early retirement (disability)

There is now scientific consensus to the effect that early retirement is a multidimensional process, and that its causes relate to society, social medicine, the law, and the individual. The percentage of tenured teachers who take early retirement is higher than for other professional groups (13, 40). In 2000, only 6% of teachers were still fit for work on reaching statutory retirement age. Of the remaining 94%, 62% retired due to illness-related disability, and 32% took early retirement because they had reached the minimum age for doing so (Figure 3). Following the comprehensive introduction of pension reductions for early retirees in 2001, illness-related retirement among teachers has halved in just a few years, and the percentage of those who are still fit for work at retirement age has markedly increased. In 2011 the mean age of the 3990 teachers who retired as a result of disability was 58 years (1). The mean age on retirement among tenured teachers rose from 57 to 63 years between 1993 and 2012. At the same time, the percentage of tenured teachers still fit for work at retirement age increased sevenfold, from 6% in 1993 to 41% in 2009. However, the percentage of those unfit for work before retirement age remains higher than in other public-sector areas. In these other areas, 17% of all retirements were due to disability in 2009 (1). Psychological and psychosomatic diseases (32% to 50%) are the most common reason for early retirement among teachers, and women tend to suffer more frequently than men (4, 13). In the states of the former East Germany, early retirement for teachers is substantially less common than among tenured teachers in the former West Germany. In 2012, for example, a total of only 417 teachers in the former East Germany retired. Of these, 116 (28%) stated disability as their reason for retiring (e2).

Figure 3.

Early retirement due to disability and attainment of statutory age limit while still fit for work among tenured teachers in Germany between 1993 in 2011 (modified according to Gehrmann [e42])

Conclusion

Changing the framework conditions for work in education does not automatically maintain or further health or fitness for work. Individual assessment and advice are important in the teaching profession.

The teaching professions require qualified occupational medical care tailored to the particular nature of teaching. This should be provided within a network of expertise including psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychosomatic specialists in addition to treating physicians.

Key Messages.

Teachers’ behavior is healthier than the mean for the population as a whole. They also have less severe cardiovascular risk factors, with the exception of hypertension.

In studies involving questionnaires, teachers report psychosomatic complaints such as exhaustion and fatigue, headaches, tension, listlessness, sleep and concentration disorders, inner restlessness, and increased irritability more frequently than the mean for other professions.

Teachers usually have fewer days’ sick leave than the mean for individuals insured with the same health insurers, and their illness duration is shorter with the exception of psychological disorders and diseases of the airway. Teachers in the former East Germany take more days’ sick leave than those in the former West Germany, and female teachers take more than male teachers.

According to population-related medical studies, in cases of unfitness for work and during sick leave psychological health problems are more severe in teachers than the mean for the population.

It is impossible to draw definite conclusions regarding the severity of burnout, as a result of varying definitions, procedures (questionnaires), and interpretations of the term.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. rer. medic. Dipl.-Math. Haufe and Dr. rer. nat. Dipl.-Psych. Seibt declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Prof. Scheuch is Business Manager of the Center for Work and Health in Saxony (Zentrum für Arbeit und Gesundheit Sachsen GmbH).

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt Bildung und Kultur. Schuljahr 2012/2013. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2014. Allgemeinbildende und berufliche Schulen. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulich K. Arbeitsbelastungen, Beziehungskonflikte, Zufriedenheit. Weinheim und Basel. Beltz: 1996. Beruf Lehrer/in. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaarschmidt U. Weinheim, Basel, Berlin: Beltz; 2005. Halbtagsjobber? Psychische Gesundheit im Lehrerberuf - Analyse eines veränderungsbedürftigen Zustandes. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheuch K, Seibt R, Rehm U, Riedel R, Melzer W. Lehrer Handbuch der Arbeitsmedizin. In: xLetzel S, Nowak D, editors. Fulda: Fuldaer Verlagsanstalt; 2010. F I-L-2 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hattie J. Abingdon/New York: Routledge; 2009. Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunter M, Klusmann U, Baumert J, et al. Professional competence of teachers: effects on instructional quality and student development. J Educ Psychol. 2013;105:805–820. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klusmann U, Kunter M, Trautwein U, et al. Engagement and emotional exhaustion in teachers: does the school context make a difference? Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2008;57:127–151. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaarschmidt U, Kieschke U. Beanspruchungsmuster im Lehrerberuf.Ergebnisse und Schlussfolgerungen aus der Potsdamer Lehrerstudie . In: Rothland M, editor. Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2013. pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schönwälder HG, Berndt J, Ströver F, Tiesler G. Bremerhaven: Wirtschaftsverlag NW; 2003. Belastung und Beanspruchung von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seibt R, Galle M, Dutschke D. Psychische Gesundheit im Lehrerberuf. Präv Gesundheitsförd. 2007;4:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seibt R, Spitzer S, Druschke D, Scheuch K, Hinz A. Predictors of mental health in female teachers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2013;26:556–569. doi: 10.2478/s13382-013-0161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer J, Stamm A, Virnich K, et al. Correlation between burnout syndrome and psychological and psychosomatic symptoms among teachers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006;79:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s00420-005-0050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber A, Weltle D, Lederer P. Frühinvalidität im Lehrerberuf: Sozial- und arbeitsmedizinische Aspekte. Dtsch Arztebl. 2004;101:A850–A-859. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seibt R, Ulbricht S, Rehm U, Steputat A, Scheuch K. Dresden: Selbstverlag der Technischen Universität Dresden; 2011. Arbeitsmedizinische Vorsorgeuntersuchungen - Bericht zur Gesundheit von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern der Sächsischen Bildungsagentur 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause A, Dorsemagen C. Gesundheitsförderung für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer: Gesundheitsförderung und Gesundheitsmanagement in der Arbeitswelt. In: Bamberg E, Ducki A, Metz AM, editors. Vol. 561. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2011. 579 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harazd B, Gieske M, Rolff HG. Belastungserleben von Lehrkräften - was Schulleiter/innen tun können: Salutogenes Leitungshandeln. In: Buchen L, Horster L, Rolff HG, editors. Schulleitung und Schulentwicklung. Stuttgart: Raabe; 2009. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seibt R, Hübler A, Steputat A, Scheuch A. Verausgabungs-Belohnungs-Verhältnis und Burnout-Risiko bei Lehrerinnen und Ärztinnen - ein Berufsgruppenvergleich. Arbeitsmed Sozialmed Umweltmed. 2012;47:396–406. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiter I. Berlin: BKK DV, DGUV, AOK-BV, vdek; 2014. Zusammenschau von Erwerbstätigenbefragungen aus Deutschland, iga-Report 26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheuch K, Vogel H. Prävalenz von Befunden in ausgewählten Diagnosegruppen bei Lehrern. Soz Präventivmed. 1993;38:20–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01321157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehr D. Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf: Gesundheitliche Situation und Evidenz für Risikofaktoren. In: Terhart E, Bennewitz H, Rothland M, editors. Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf. Münster: Waxmann; 2011. pp. 757–773. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaschka WP, Korczak D, Broich K. Burnout: A fashionable diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:781–787. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blossfeld HP, Bos W, Daniel HD, et al. Münster: Waxmann; 2014. Vereinigung der Bayerischen Wirtschaft e. V. Münster (eds.)Aktionsrat Bildung. Gutachten Psychische Belastungen und Burnout beim Bildungspersonal. Empfehlungen zur Kompetenz- und Organisationsentwicklung. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheuch K, Seibt R. Arbeits- und persönlichkeitsbedingte Beziehungen zu Burnout - eine kritische Betrachtung. Arbeit und Gesundheit. Zum aktuellen Stand in einem Forschungs- und Praxisfeld. In: Richter PG, Rau R, Mühlpfordt S, editors. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2007. pp. 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hapke U, Maske UE, Scheidt-Nave C, et al. Chronischer Stress bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:749–754. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1690-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gieske M, Harazd B. Theoretischer Hintergrund und Forschungsstand zur Lehrergesundheit. In: Harazd B, Gieske, Rolff H-G, editors. Gesundheitsmanagement in der Schule. Lehrergesundheit als neue Aufgabe der Schulleitung. Köln: LinkLuchterhand; 2009. pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nübling M, Vomstein M, Haug A, et al. Freiburg: Freiburger Forschungsstelle Arbeits- und Sozialmedizin; 2012. Personenbezogene Gefährdungsbeurteilung an öffentlichen Schulen in Baden-Württemberg - Erhebung psychosozialer Faktoren bei der Arbeit. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unterbrink T, Hack A, Pfeifer R, et al. Burnout and effort-reward-imbalance in a sample of 949 German teachers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;80:433–441. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wegner R, Berger P, Poschadel B, Manuwald U, Baur X. Burnout hazard in teachers results of a clinical psychological intervention study. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2011;6:37–42. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Böckelmann I, Zavgorodnij I, Iakymenko M, et al. Professional burnout syndrome among teachers of Ukraine and Germany. Sci J Ministry Health Ukraine. 2013;3:163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population - results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schumacher L, Nieskens B, Sieland B, et al. Handbuch Lehrergesundheit - Impulse für die Entwicklung guter gesunder Schulen. Köln: Carl Link; 2012. DAK-Gesundheit & Unfallkasse NRW (eds) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohmann-Haislah A. Stressreport Deutschland 2012 Psychische Anforderungen, Ressourcen und Befinden. Dortmund: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. (1. Auflage) 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauer J. Burnout bei schulischen Lehrkräften. Psychotherapie im Dialog. 2009;10:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillert A, Koch S, Lehr D. Das Burnout-Phänomen am Beispiel des Lehrerberufs. Paradigmen, Befunde und Perspektiven berufsbezogener Therapie- und Präventionsansätze. Nervenarzt. 2013;84:806–812. doi: 10.1007/s00115-013-3745-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nübling M, Vomstein M, Haug A, et al. European-wide survey on teachers work related stress - assessment, comparison and evaluation of the impact of psychosocial hazards on teachers at their workplace. www.etuce.homestead.com/Publications2011/Final_Report_on_the_survey_on_WRS-2011-eng.pdf. (last accessed on 1 December 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berger M, Linden M, Schramm E, Hillert A, Voderholzer U, Maier W. Positionspapier der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) zum Thema Burnout. www.dgppn.de/fileadmin/user_upload/_medien/dokumente/dgppn-veranstaltungen/2012-03-07hsburnout/praesentationsfolienberger.pdf. (last accessed on 17 March 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badura B, Ducki A, Schröder H, Klose J, Meyer M, editors. Zahlen, Daten, Analysen aus allen Branchen der Wirtschaft. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. Fehlzeiten-Report 2014. Erfolgreiche Unternehmen von morgen - gesunde Zukunft heute gestalten. [Google Scholar]

- 38.DAKG esundheit. Gesundheit im Spannungsfeld von Job, Karriere und Familie. Berlin: IGES Institut GmbH; 2014. Gesundheitsreport 2014. Analyse der Arbeitsunfähigkeitsdaten. Die Rushhour des Lebens. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Techniker Krankenkasse. Veröffentlichungen zum Betrieblichen Gesundheitsmanagement der TK, Band 29. Hamburg: TKK; 2014. Gesundheitsreport 2014. Risiko Rücken. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hundeloh H. Weinheim, Basel. Beltz; 2012. Gesundheitsmanagement an Schule - Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung als Aufgaben der Schulleitung. [Google Scholar]

- e1.Eurydice. eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/key_data_series/151EN.pdf. Key data on teachers and school leaders. Brüssel:Exekutivagentur Bildung, Audiovisuelles und Kultur 2013. (last accessed on 18 March 2015) [Google Scholar]

- e2.Statistisches Bundesamt. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt 2014.; FS 14, Reihe 6.1, Versorgungsempfänger öffentlicher Dienst 2013. Versorgungsempfänger des öffentlichen Dienstes. www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/FinanzenSteuern/OeffentlicherDienst/Versorgungsempfaenger2140610137004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed on 18 March 2015) [Google Scholar]

- e3.Dudenhöffer S, Claus M, Schöne K, et al. Schwerpunkt: Förderschulen. Schuljahr 2011/2012. Mainz: Universitätsmedizin, Institut für Lehrergesundheit; 2013. Gesundheitsbericht der Lehrkräfte und Pädagogischen Fachkräfte in Rheinland-Pfalz. [Google Scholar]

- e4.Rothland M, Klusmann U. Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. In: Rahm S, Nerowski C, editors. Enzyklopädie Erziehungswissenschaft Online (EEO), Fachgebiet Schulpädagogik. Weinheim: Juventa; 2012. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- e5.Klassen RM. Teacher stress: the mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. J Edu Res. 2010;103:342–350. [Google Scholar]

- e6.Mazzola JJ, Schonfeld IS, Spector P. What qualitative research has taught us about occupational stress. Stress Health. 2011;27:93–110. doi: 10.1002/smi.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Shirom A, Oliver A, Stein E. Teachers’ stressors and strains: a longitudinal study of their relationships. Int J Stress Manage. 2009;16:312–332. [Google Scholar]

- e8.Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S. Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: a study of relations. Teach Teach Educ. 2009;26:1059–1069. [Google Scholar]

- e9.Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer MJ, et al. Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:302–307. doi: 10.1136/oem.56.5.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Stansfield SA, Head JRS, Singleton N, Lee A. London: HSE Books; 2003. Occupation and mental health: secondary analysis of the ONS psychiatric morbidity survey of Great Britain. [Google Scholar]

- e11.Bogaert I, De Martelaer K, Deforche B, et al. Associations between different types of physical activity and teachers’ perceived mental, physical, and work-related health. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1492–1511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Borrelli I, Benevene P, Fiorilli C, et al. Working conditions and mental health in teachers: a preliminary study. Occup Med. 2014;64:530–532. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Ferreira AI, Martinez LF. Presenteeism and burnout among teachers in public and private Portuguese elementary schools. Int J Hum Res Manage. 2012;23:4380–4390. [Google Scholar]

- e14.Louw D, George E, Esterhuyse K. Burnout amongst urban secondary school teachers in Namibia SAJIP. S Afr J Ind Psychol. 2011;37:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- e15.Otero López J, Bolaño C, Santiago Mariño M, Pol E. Exploring stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in secondary school teachers. Int J Psychol Psychol Therapy. 2010;10:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- e16.Rey L, Extremera N, Pena M. Burnout and work engagement in teachers: are sex and level taught important? Ansiedad Y Estrés. 2012;18:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- e17.Shin H, Noh H, Jang Y, et al. A longitudinal examination of the relationship between teacher burnout and depression. J Employment Couns. 2013;50:124–137. [Google Scholar]

- e18.Steinhardt M, Smith Jaggars S, Faulk K, Gloria C. Chronic work stress and depressive symptoms: assessing the mediating role of teacher burnout. Stress Health. 2011;27:420–429. [Google Scholar]

- e19.Tang J, Leka S, MacLennan S. The psychosocial work environment and mental health of teachers: a comparative study between the United Kingdom and Hong Kong. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s00420-012-0799-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Verhoeven C, Maes S, Kraaij V, Joekes K. The Job Demand-Control-Social Support Model and wellness/health outcomes: a European Study. Psychol Health. 2003;18:421–440. [Google Scholar]

- e21.Vladut CI, Kállay É. Psycho-emotional and organizational aspects of burnout in a sample of romanian teachers. Cogn Brain Behav. 2011;15:331–358. [Google Scholar]

- e22.Griebler R. Gesundheitszustand österreichischer Lehrerinnen und Lehrer. In: Dür W, Felder-Puig R, editors. Lehrbuch schulische Gesundheitsförderung. Bern: Huber; 2011. pp. 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- e23.Neuhauser H, Thamm M, Ellert U. Blutdruck in Deutschland 2008-2011- Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:795–801. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Mensink GBM, Schienkiewitz A, Haftenberger M, et al. Übergewicht und Adipositas in Deutschland - Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:786–794. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Scheidt-Nave C, Du Y, Knopf H, et al. Verbreitung von Fettstoffwechselstörungen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland - Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:661–667. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Krug S, Jordan S, Mensink GBM, et al. Körperliche Aktivität - Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:765–771. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Lampert T, von der Lippe E, Müters S. Verbreitung des Rauchens in der Erwachsenenbevölkerung in Deutschland - Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:802–808. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Höck K, Hess H. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften; 1975. Der Beschwerdenfragebogen (BFB) [Google Scholar]

- e29.Hasselhorn HM, Freude G. Der Work Ability Index - ein Leitfaden. Bremerhaven: Wirtschaftsverlag NW Verlag für neue Wissenschaft GmbH. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- e30.Oberdoerster G. Prävalenz ausgewählter chronischer Krankheiten bei Werktätigen - Ergebnisse arbeitsmedizinischer Vorsorgeuntersuchungen. Z ges Hyg. 1987;33:567–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burn-out Inventory—General Survey. In: Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, editors. The Maslach Burnout Inventory test manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- e32.Seibt R, Hübler A, Steputat A, Scheuch K. Verausgabungs-Belohnungs-Verhältnis und Burnout-Risiko bei Lehrerinnen und Ärztinnen - ein Berufsgruppenvergleich. Arbeitsmed Sozialmed Umweltmed. 2012;7:396–406. [Google Scholar]

- e33.Symonds TL, Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ. Do attitudes and beliefs influence work loss due to low back trouble? Occup Med. 1996;46:25–32. doi: 10.1093/occmed/46.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M. Boston: The Health Institute; 1993. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. [Google Scholar]

- e35.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- e36.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Ruy JY, Park SH, Yoon SK. The factors associated with psychological burnout of helping professional, counselors and teachers. Korean J Youth Counseling. 2003;11:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- e38.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, et al. The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1483–1499. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Derogatis LR. Baltimore, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1977. SCL-90-R: Administration, scoring and procedures manual-I. [Google Scholar]

- e41.Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK (WIdO) (ed) Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK (WIdO) Berlin: WidO; 2014. Sep 20, Krankenstand von AOK-versicherten Lehrkräften an allgemeinbildenden Schulen in Deutschland 2012 und 2013 - Sonderauswertung. [Google Scholar]

- e42.Gehrmann A. Zufriedenheit trotz beruflicher Beanspruchung? Anmerkungen zu den Befunden der Belastungsforschung. In: Rothland M, editor. Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. Modelle, Befunde, Interventionen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]