Comparative analysis in Arabidopsis ecotypes, hybrids, and tetraploids revealed the presence of natural variation in early reproductive development that depends on the function of epigenetic pathways.

Abstract

In angiosperms, the transition to the female gametophytic phase relies on the specification of premeiotic gamete precursors from sporophytic cells in the ovule. In Arabidopsis thaliana, a single diploid cell is specified as the premeiotic female gamete precursor. Here, we show that ecotypes of Arabidopsis exhibit differences in megasporogenesis leading to phenotypes reminiscent of defects in dominant mutations that epigenetically affect the specification of female gamete precursors. Intraspecific hybridization and polyploidy exacerbate these defects, which segregate quantitatively in F2 populations derived from ecotypic hybrids, suggesting that multiple loci control cell specification at the onset of female meiosis. This variation in cell differentiation is influenced by the activity of ARGONAUTE9 (AGO9) and RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE6 (RDR6), two genes involved in epigenetic silencing that control the specification of female gamete precursors. The pattern of transcriptional regulation and localization of AGO9 varies among ecotypes, and abnormal gamete precursors in ovules defective for RDR6 share identity with ectopic gamete precursors found in selected ecotypes. Our results indicate that differences in the epigenetic control of cell specification lead to natural phenotypic variation during megasporogenesis. We propose that this mechanism could be implicated in the emergence and evolution of the reproductive alternatives that prevail in flowering plants.

INTRODUCTION

The life cycle of flowering plants alternates between a dominant, diploid, sporophytic generation and a short-lived, haploid, gametophytic generation in specialized reproductive organs. Integration between environmental signals and developmental programs that control flowering initiates development of the female reproductive lineage within the gynoecium. During early formation of the gynoecium in Arabidopsis thaliana, ovule primordia develop from the placenta as finger-like protrusions by active cell divisions in the subepidermal layer (Schneitz et al., 1995; Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998; Ferrándiz et al., 1999). A single cell is specified as the archeospore, which directly differentiates into the premeiotic gamete precursor known as the megaspore mother cell (MMC). The MMC subsequently divides by meiosis to produce four haploid cells, one of which is specified as the functional megaspore (FM), the first cell of the female gametophytic phase. The FM develops by three rounds of mitosis into a female gametophyte, containing three antipodal cells, two synergids, the egg, and a binucleated central cell. After double fertilization, the egg and the central cell will develop into the embryo and the endosperm, respectively (Reiser and Fischer, 1993; Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998; Drews and Koltunow, 2011).

This pattern of development characteristic of Arabidopsis and the majority of flowering plants is known as the monosporic, Polygonum-type of female gametogenesis (Maheshwari, 1950; Eames, 1961). Although the Polygonum-type prevails in most angiosperms examined to date (Huang and Russell, 1992), there are many examples of naturally occurring variations that affect cell specification in the ovule during female meiosis or gametogenesis. These variations often involve the emergence of several female gamete precursors (Vandendries, 1909; Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998; Bachelier and Friedman, 2011), the incorporation of more than one meiotically derived product to the female gametophyte (Maheshwari, 1950; Madrid and Friedman, 2009), the formation of nonreduced female gametophytes (Karpechenko, 1927; Bretagnolle and Thompson, 1995; Ramsey and Schemske, 1998), or the formation of seeds through asexual reproduction by a process known as apomixis that bypasses meiosis and fertilization (Grimanelli et al., 2001; Koltunow and Grossniklaus, 2003). Although extensive comparative and morphological reports describing these alternatives are available for many angiosperm taxa, the genetic basis and molecular mechanisms that control this type of reproductive natural variation remain unclear.

Several genes are known to be involved in the control of gamete cell specification and meiosis, and they act either by restricting the number of meiotic precursors or by enabling the progression through the meiotic division (Sheridan et al., 1996; Ferrándiz et al., 1999; Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Nonomura et al., 2003; Lieber et al., 2011). In addition, epigenetic components mediated by the action of small RNAs (sRNAs) have been described as important regulators of cell specification and female gametogenesis in Arabidopsis (Armenta-Medina et al., 2011; Rodríguez-Leal and Vielle-Calzada, 2012). sRNAs are 18- to 30-nucleotide RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level by their association with members of the ARGONAUTE (AGO) protein family. Several classes of sRNAs have been defined, depending on their mechanisms of biogenesis and action (Ghildiyal and Zamore, 2009). The function of AGO9 and other specific members of the so-called RNA-directed DNA methylation or trans-acting small interfering RNA pathways are important for the correct specification of female gamete precursors. Mutations in genes such as RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE6 (RDR6), DICER-LIKE3, and AGO9 exhibit increased frequency of abnormal gamete precursors that often give rise to more than one female gametophyte developing in the Arabidopsis ovule (Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010). Additional roles for sRNAs and their interactors in female meiosis and gametogenesis have been described, suggesting that some epigenetic pathways are crucial for the establishment of the gametophytic generation (Nonomura et al., 2007; García-Aguilar et al., 2010; Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2011; Tucker et al., 2012).

Here, we report a detailed analysis of the phenotypic effects of natural variation in the control of gamete precursor specification in the developing ovule of Arabidopsis. We show that in phylogenetically distant ecotypes, the mechanisms that specify gamete precursors are naturally variable, and they often lead to the differentiation of supernumerary cells as premeiotic precursors. Moreover, the frequency at which these ectopic cell configurations occur is increased in F1 hybrids of specific ecotypes, and the prevalence of ectopic cells at late stages of megasporogenesis is increased in tetraploid individuals. We also show that the genetic introgression of mutations affecting the function of AGO9 or RDR6 is buffered by allelic interactions in the ovule of ecotypic F1 hybrids and that the complete loss of AGO9 activity disrupts this mitigating effect. Finally, we demonstrate that the patterns of transcriptional regulation and protein localization of AGO9 are variable between ecotypes and that the abnormal gamete precursors found in mutants defective in RDR6 share a cellular identity with the ectopic cells naturally found in specific ecotypes. Our results link previously characterized epigenetic pathways to mechanisms of natural variation that affect the specification of female gamete precursors in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

Selected Ecotypes of Arabidopsis Show Natural Variation in Cell Differentiation during Megasporogenesis, Which Is Influenced by Intraspecific Hybridization and Ploidy

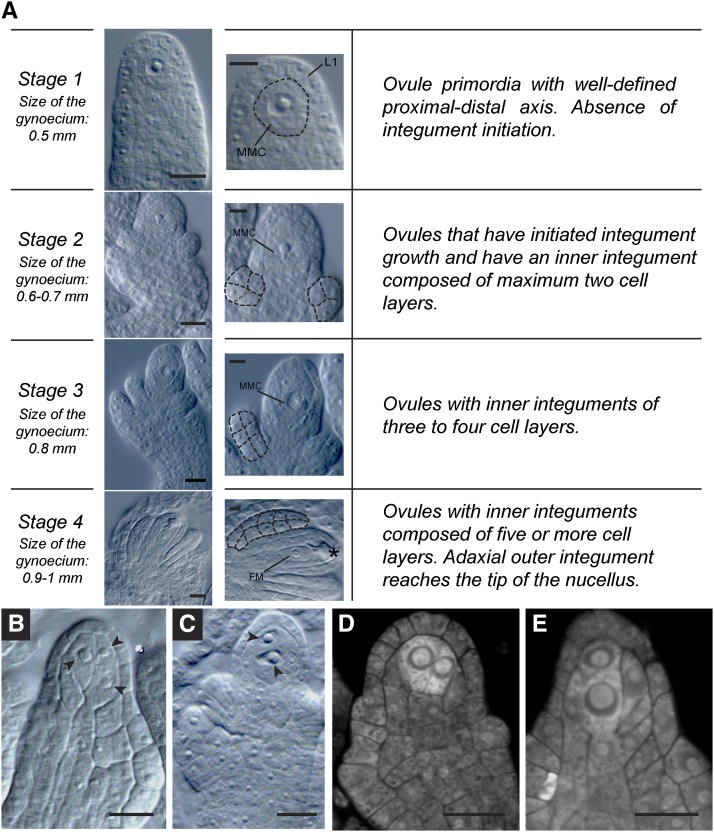

Previous reports showed that in most cases of megasporogenesis in Arabidopsis, a single subepidermal cell in the ovule primordium is specified as the MMC (Vandendries, 1909; Schneitz et al., 1995). The MMC enters meiosis and gives rise to four haploid cells, of which only one survives to develop a into female gametophyte. To further characterize the timeframe of cell differentiation in the apical region of the developing ovule, we correlated premeiotic to postmeiotic cellular differentiation with integumentary growth in five genetically distant ecotypes of Arabidopsis and their respective hybrids (Figure 1). In addition to the reference ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0), we selected Shakdara-0 (Sha-0), Borky-4 (Bor-4), Cape Verde Islands-0 (Cvi-0), and Monterrosso-0 (Mr-0) as four genetically distant ecotypes with a contrasting pattern of geographic and environmental distribution (Nordborg et al., 2005). As presented in Figure 1A and Table 1, four temporal stages that encompass megasporogenesis were defined to score cell differentiation and division. We defined Stage 1 as corresponding to ovule primordia having a well-defined proximal-distal axis and the absence of integument initiation. Stage 2 comprises ovules that have initiated integument growth and have an inner integument composed of a maximum of two cell layers. In Stage 3 ovules, both integuments have initiated growth and development, and the inner integument has three to four cell layers. Finally, Stage 4 ovules contain an inner integument of at least five cell layers and an adaxial outer integument that reaches the tip of the nucellus.

Figure 1.

Ovule Morphology and Gamete Precursor Cell Differentiation at Four Stages of Ovule Development in Arabidopsis.

(A) Temporal stages encompassing megasporogenesis as defined on the basis of integument growth. Asterisk indicates the presence of a degenerated megaspore. L1, L1 cell layer.

(B) Bor-4 ovule with three differentiated female gamete precursors (arrowheads).

(C) Cvi-0 ovule with two differentiated female gamete precursors (arrowheads).

(D) and (E) Confocal sections showing Mr-0 ovules containing female gamete precursors showing higher intensity of propidium iodide staining compared with adjacent sporophytic cells.

Bars = 10 μm in (A), 5 μm in inset in (A), and 10 μm in (B) to (E).

Table 1. Quantitative Analysis of Cell Differentiation during Megasporogenesis in Ovules of Arabidopsis Ecotypes, Their Wild-Type Hybrid, and Tetraploid Lines.

| Stage 1 |

Stage 2 |

Stage 3 |

Stage 4 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Single MMC (%) | Ectopic Configurations (%) | Total | Single MMC (%) | Ectopic Configurations (%) | Total | Single MMC (%) | Ectopic Configurations (%) | Total | Functional Megaspore (%) | Ectopic Configurations (%) | Total |

| Col-0 | 478 (90.4) | 51 (9.6) | 529 | 578 (89.6) | 67 (10.4) | 529 | 593 (96.1) | 24 (3.9) | 529 | 257 (99.2) | 2 (0.8) | 529 |

| Ler | 282 (83.7) | 55 (16.3) | 337 | 325 (89.5) | 38 (10.5) | 337 | 245 (96.1) | 10 (3.92) | 337 | 210 (95.5) | 10 (4.55) | 337 |

| Sha-0 | 379 (95.2) | 19 (4.8) | 398 | 705 (96.6) | 25 (3.4) | 398 | 500 (99.2) | 4 (0.8) | 398 | 197 (100) | 0 (0) | 398 |

| Bor-4 | 620 (89.5) | 73 (10.5) | 693 | 702 (93) | 53 (7) | 693 | 335 (95.4) | 16 (4.6) | 693 | 287 (99) | 3 (1) | 693 |

| Cvi-0 | 314 (88.5) | 41 (11.5) | 355 | 335 (92.5) | 27 (7.5) | 355 | 241 (93.8) | 16 (6.2) | 355 | 266 (100) | 0 (0) | 355 |

| Mr-0 | 303 (72.7) | 114 (27.3) | 417 | 339 (82.9) | 70 (17.1) | 409 | 339 (96.3) | 13 (3.7) | 352 | 296 (98) | 6 (2) | 302 |

| Col-0 × Sha-0 F1 | 491 (88.2) | 66 (11.8) | 557 | 612 (92) | 13 (8) | 625 | 453 (97.4) | 12 (2.6) | 465 | 190 (98.4) | 3 (1.6) | 193 |

| Col-0 × Bor-4 F1 | 323 (78.6) | 88 (21.4) | 411 | 311 (79.7) | 79 (20.3) | 390 | 269 (91.2) | 26 (8.8) | 295 | 291 (98.3) | 5 (1.7) | 296 |

| Col-0 × Cvi-0 F1 | 174 (71.3) | 70 (28.7) | 244 | 305 (86.9) | 46 (13.1) | 351 | 249 (89.9) | 28 (10.1) | 277 | 255 (98.1) | 5 (1.9) | 260 |

| Col-0 × Mr-0 F1 | 401 (77.4) | 117 (22.6) | 518 | 251 (83.9) | 48 (16.1) | 299 | 313 (93.7) | 21 (6.3) | 334 | 174 (96.1) | 7 (3.9) | 181 |

| Col 4N | 282 (70.1) | 120 (29.9) | 402 | 534 (85.9) | 88 (14.1) | 622 | 355 (97.3) | 10 (2.7) | 365 | 158 (89.3) | 19 (10.7) | 177 |

| Ler 4N | 292 (75.8) | 93 (24.2) | 385 | 335 (82.7) | 70 (17.3) | 405 | 253 (97.7) | 6 (2.3) | 259 | 275 (96.2) | 11 (3.8) | 286 |

All four stages encompass the main cellular events occurring during megasporogenesis, up to the differentiation of the FM at the onset of megagametogenesis. For Stages 1 to 3, the majority of ovules in all five ecotypes showed a single conspicuous MMC with a dense cytoplasm, large nucleus, and prominent nucleolus, occupying a preponderant position in direct contact with the apical L1 layer. At these same stages, all five ecotypes also showed variable frequencies of ovules harboring more than one cell reminiscent of the MMC (Figures 1B to 1E); these alternative morphological events were named ectopic configurations. Mr-0 was the most variable ecotype, with nearly 30% of ovules showing ectopic configurations at Stage 1 (Table 1; Supplemental Table 1). Following the developmental progression from Stages 1 to 4, the frequency of ectopic configurations declined in all ecotypes, being almost absent at Stage 4, suggesting developmental competition between neighboring ectopic cells (Table 1). In all cases where ectopic configurations were observed, a single linear arrangement of degenerated cells adjacent to a surviving megaspore was observed at Stage 4, suggesting that a single cell divided meiotically.

We also quantified cell differentiation during megasporogenesis in F1 individuals resulting from intraspecific crosses between Col-0 and each of the additional four selected ecotypes. The results were analyzed using a χ2 test. As shown in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2, the phenotypic frequencies revealed cases of both additive and nonadditive effects, depending on the parental combinations and the developmental stage analyzed. When compared with their mid-parent value (i.e., the average phenotype frequency observed in the parental lines), F1 individuals resulting from crosses between Col-0 and Sha-0 showed additive effects in Stages 1, 3, and 4, while F1 plants from crosses between Col-0 and Bor-4 or Cvi-0 ecotypes exhibited nonadditive phenotypic frequencies at different stages. Whereas for Col-0 × Cvi-0 F1 individuals nonadditivity was confirmed for Stages 1 and 3, Col-0 × Bor-4 F1 hybrids showed the same pattern from Stages 1 to 3. A statistically significant suppressive effect on the frequency of ectopic configurations was observed in the Col-0 × Sha-0 F1 individuals, suggesting that in this cross nonadditive effects are associated with reduction of ectopic configurations. In the case of Col-0 × Mr-0 F1 hybrids, a nonadditive effect was only present across Stages 1 and 2. In all genetic combinations, the trend in phenotypic frequencies was consistent in reciprocal crosses, showing that the selection of an ecotype as a maternal or paternal parent did not influence the F1 results (Supplemental Table 1).

Finally, we quantified cell differentiation during megasporogenesis in tetraploid individuals of Col-0 and Landsberg erecta (Ler). Both ecotypes exhibited high frequencies of ovules showing ectopic configurations compared with their diploid counterparts (29.9% for Col-0; 24.2% for Ler at Stage 1). Although in both ecotypes the frequency of ectopic configurations decreased during the progression of megasporogenesis, 10.7% of Col-0 ovules showed ectopic configurations at Stage 4—a frequency significantly higher than diploid ovules of this same ecotype (0.8%) at that stage—suggesting that dosage factors are able mitigate the developmental mechanisms that favor competition between neighboring gamete precursors. Overall, these results indicate that premeiotic gamete cell specification is naturally variable in the ovule of Arabidopsis, with a strong tendency toward restricting the persistence of ectopic configurations at late stages of megasporogenesis. They also show that specific allelic combinations have a tendency to increase the differentiation of ectopic cells at the onset of meiosis, whereas higher ploidy levels in specific ecotypes tend to increase the prevalence of ectopic cells at late stages of megasporogenesis.

The Frequency of Ectopic Cells in the Ovule Segregates Continuously among Individuals of Wild-Type F2 Populations

To determine whether multiple segregating factors could contribute to the variability found in gamete precursor cell specification, the frequency of ovules showing ectopic configurations was quantified in a population of F2 individuals from two different crosses that previously exhibited nonadditive effects (Col-0 × Cvi-0 and Col-0 × Bor-4). For ∼50 F2 individuals per cross, close to 100 ovules were cytologically analyzed at Stage 1 in both segregating populations (Figure 2). In both cases, the phenotypic frequencies of ectopic configurations followed a normal distribution, broadly coalescing in seven distinct phenotypic classes (Shapiro-Wilk test for normality, P > 0.7; Figure 2; Supplemental Table 3), with transgression beyond the maximum limit reached by the parents in both F2 populations (up to 40%). Although subtle differences in phenotypic frequencies were observed between the two segregating populations, the broad categories were conserved, indicating that the same number of factors in both populations are contributing to the control of the cell specification trait. This result suggests that several discrete genetic factors are influencing the specification of gamete precursors during early ovule development in Arabidopsis and that they contribute additively to phenotype frequency of ovules with ectopic cells, favoring a quantitative genetic control of cell specification.

Figure 2.

Segregation of Ovules Showing Ectopic Configurations in F2 Populations Originating from Ecotypic F1 Hybrids.

(A) Frequency of ovules showing ectopic configurations in Col-0 × Cvi-0 F2 individuals.

(B) Frequency of ovules showing ectopic configurations in Col-0 × Bor-4 F2 individuals.

Ecotypic Variation in Cell Differentiation Is Influenced by the Activity of AGO9

The presence of ectopic configurations at variable frequencies in ecotypes of Arabidopsis is reminiscent of phenotypes found in dominant ago9 and rdr6 loss-of-function mutants. Plants defective in AGO9 or RDR6 showed ectopic differentiation of female gamete precursors and subsequent formation of extranumerary female gametophytes in the developing ovule (Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010). To investigate a possible involvement of these sRNA-related genes in the natural ecotypic variation during megasporogenesis, we quantified the frequency of ectopic configurations in F1 progeny resulting from the cross of ago9-3 (Col-0) individuals with Bor-4, Sha-0, Cvi-0, and Mr-0 plants (Table 2). Whereas heterozygous F1 individuals resulting from a cross between homozygous ago9-3 and Sha-0 showed an additive increase in ovules exhibiting ectopic configurations (Table 2), F1 plants from homozygous ago9-3 crossed to Bor-4, Cvi-0, and Mr-0 showed no increase in the frequency of ovules showing ectopic configurations compared with heterozygous ago9-3/+ or their corresponding wild-type ecotypic hybrids. A similar tendency was detected in reciprocal crosses between rdr6-15 mutants (Col-0) and Cvi-0, indicating that the effect of dominant ago9 or rdr6 mutations in the ectopic configuration phenotype is buffered in ecotypic hybrids, as the introduction of a dominant ago9 or rdr6 allele did not result in an increase in the number of ovules showing ectopic configurations. These results confirm that a high frequency of ectopic configurations in F1 hybrids resulting from crosses between Col-0 and Bor-4 or Cvi-0 is likely related to divergent allelic combinations. Interestingly, homozygous ago9-3 F1 hybrids resulting from a cross between ago9-3 and BC4 heterozygous ago9-3/+ plants introgressed into a Bor-4 background showed frequencies of ectopic configurations in Stage 1 ovules equivalent to those found in homozygous ago9-3 (Col-0) individuals (χ2 = 2.35 < χ2 0.05[1] = 3.84; Table 2). Since homozygous ago9-3 mutants were previously shown to lack any AGO9 activity (Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010), this result indicates that the buffering effect described above is overcome by the complete loss of function of AGO9. Our results suggest that although hybridization between some phylogenetically distant ecotypes perturbs the process of gamete precursor cell specification at quantitative levels similar to those observed in mutants defective in AGO9 function, the introduction of mutations affecting AGO9 or RDR6 activity is buffered by complex allelic interactions in specific ecotypic F1 hybrids. They also show that the complete absence of AGO9 activity disrupts this buffering effect, revealing a genetic interaction between the natural mechanisms that control ecotypic variation during megasporogenesis and the function of AGO9.

Table 2. Quantitative Comparison among Wild-Type and Mutant Ecotypic Hybrids at Stage 1.

| Genotype | Single MMC (%) | Ectopic Configurations (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 × Sha-0 F1 | 491 (88.2) | 66 (11.8) | 557 |

| ago9-3 × Sha-0 F1 | 646 (78.4) | 178 (21.6) | 824 |

| Col-0 × Cvi-0 F1 | 174 (71.3) | 70 (28.7) | 244 |

| ago9-3 × Cvi-0 F1 | 228 (76.0) | 72 (24.0) | 300 |

| rdr6-15 × Cvi-0 F1 | 372 (77) | 111 (23) | 483 |

| Col-0 × Mr-0 F1 | 401 (77.4) | 117 (22.6) | 518 |

| ago9-3 × Mr-0 F1 | 303 (73.2) | 111 (26.8) | 414 |

| Col × Bor-4 F1 | 323 (78.6) | 88 (21.4) | 411 |

| ago9-3 × Bor-4 F1 | 560 (78.4) | 154 (21.6) | 714 |

| ago9-3 × BC ago9-3 (Bor-4) −/− F1 | 396 (73.9) | 140 (26.1) | 536 |

| ago9-3/+ | 371 (75.3) | 122 (24.7) | 493 |

| rdr6-15/+ | 369 (68.6) | 169 (31.4) | 538 |

| ago9-3 | 551 (70) | 236 (30) | 787 |

Natural Variation in Genomic Regulatory Regions of AGO9 Results in Changes in Transcriptional Regulation and Protein Localization

To determine whether differences in AGO9 expression could help explain differences in the frequency of ectopic configurations found between Col-0 and Mr-0 ecotypes, we conducted mRNA whole-mount in situ hybridization in developing ovules of Col-0 and Mr-0 individuals using a 149-bp antisense RNA probe corresponding to a Col-0 sequence located in the 3′ untranslated region (Supplemental Figure 1). As expected from previous results, in both genetic backgrounds, AGO9 mRNA was localized in all cells of the ovule primordium throughout megasporogenesis. However, under identical experimental conditions, the level of mRNA expression was consistently higher in developing ovules of Col-0 compared with Mr-0 ovules. Because the level of genomic polymorphisms between Col-0 and Mr-0 within the sequence corresponding to the selected probe is not sufficient to cause deficiencies in the formation of antisense RNA:mRNA duplexes to explain this difference (Supplemental Figure 1), these in situ hybridization results suggest that AGO9 mRNA is weakly expressed in Mr-0 ovules. To determine whether this difference in AGO9 expression is related to ecotypic differences in AGO9 transcriptional regulation, the complete 2619-bp intergenic region upstream of the AGO9 coding sequence isolated from either Col-0 or Mr-0 plants was cloned in front of the uidA (β-glucuronidase [GUS]) reporter gene to subsequently transform Col-0 wild-type individuals. Stage 1 ovules of Col-0 plants transformed with a transcriptional fusion that includes the Col-0 AGO9 regulatory sequence (proCol-0AGO9:GUS) showed strong GUS expression after 6 h of histochemical incubation, with initial expression in the nucellar cells located at the proximal pole of the MMC (99%, n = 110). At Stage 2, GUS expression was localized in additional nucellar cells and in the L1 layer. At Stage 4, GUS expression prevailed in the chalazal region of the ovule (Figures 3A to 3C). In contrast, ovules of Col-0 plants transformed with a transcriptional fusion that includes the Mr-0 AGO9 regulatory sequence (proMr-0AGO9:GUS) showed GUS expression only after 24 to 36 h of histochemical incubation in a pattern antagonistic to developing ovules of proCol-0AGO9:GUS transformants. The majority of proMr-0AGO9:GUS ovules at Stage 1 (88%, n = 568) showed GUS expression restricted to L1 cells located at the apical (distal) pole of the MMC. Although Stage 2 ovules showed GUS expression restricted to a larger number of L1 cells in the same region, Stage 4 ovules showed GUS expression in a pattern similar but not identical to Stage 4 ovules in proCol-0AGO9:GUS transformants (Figures 3D to 3F), since GUS expression in the subepidermal apical region remains strong in proMr-0AGO9:GUS transformants.

Figure 3.

Reporter Gene Expression in proCol-0AGO9:GUS and proMr-0AGO9:GUS Transgenic Lines in a Col-0 Background.

(A) Stage 1 ovule of a transgenic proCol-0AGO9:GUS plant.

(B) Stage 2 ovule of a transgenic proCol-0AGO9:GUS plant.

(C) Stage 4 ovule of a transgenic proCol-0AGO9:GUS plant.

(D) Stage 1 ovule of a transgenic proMr-0AGO9:GUS plant.

(E) Stage 2 ovule of a transgenic proMr-0AGO9:GUS plant.

(F) Stage 4 ovule of a transgenic proMr-0AGO9:GUS plant.

(G) Stage 1 ovule of a Sha-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS (Col-0) F1 plant.

(H) Stage 1 ovule of a Bor-4 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS (Col-0) F1 plant.

(I) Stage 1 ovule of a Cvi-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS (Col-0) F1 plant.

(J) Stage 4 ovule of a Sha-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS (Col-0) F1 plant.

(K) Stage 4 ovule of a Bor-4 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS (Col-0) F1 plant.

(L) Stage 4 ovule of a Cvi-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS (Col-0) F1 plant.

The nucellar region is highlighted by dashed lines in (A). Arrows indicate the presence of gamete precursors in (A), (B), (D), (E), and (G) to (I), and the functional megaspore is highlighted in (C) and (F). Asterisks indicate the presence of degenerated megaspores in (C) and (F). Bars = 10 μm in (A), (B), (D), (E), and (G) to (I) and 20 μm in (C), (F), and (J) to (L).

We also determined the pattern of AGO9 transcriptional regulation in developing ovules of F1 plants generated by crossing individuals of Sha-0, Bor-4, and Cvi-0 to the proCol-0AGO9:GUS Col-0 line (Figures 3G to 3L). Whereas the general pattern of GUS expression was reminiscent of the pattern found in ovules of Col-0, ovules of F1 individuals exhibited specific differences at both premeiotic and postmeiotic stages (Stages 1 and 4). At Stage 1, whereas Sha-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS F1 ovules showed a pattern equivalent to Col-0 (Figure 3G), GUS expression was substantially reduced in Bor-4 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS and Cvi-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS F1 ovules (Figures 3H and 3I). Also, whereas initial GUS expression in Col-0 ovules was in most nucellar cells located at the proximal pole of the MMC, Bor-4 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS F1 individuals showed initial expression in a small cluster comprising L2 and L3 cells at the midlateral region of the premeiotic primordium (Figure 3H). At Stage 4, Bor-4 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS and Cvi-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS F1s also showed reduced GUS expression compared with Sha-0 × proCol-0AGO9:GUS F1 and Col-0 ovules (Figures 3J to 3L), indicating that in these F1 individuals AGO9 expression is reduced throughout megasporogenesis. Taken together, these results suggest that the factors controlling transcriptional regulation of AGO9 are variable among ecotypes and their hybrids. They also suggest that although divergent regulation of the Mr-0 AGO9 promoter region in the Col-0 background can cause antagonistic changes in the spatial pattern of reporter gene expression, additional genetic factors are likely to compensate these changes to produce similar but not identical spatial patterns of transcriptional regulation at subsequent stages of ovule development.

To determine the pattern of AGO9 protein expression in ovules of selected ecotypes, we conducted whole-mount immunolocalizations using a polyclonal antibody previously reported to specifically recognize an epitope of the AGO9 protein. Previous experiments showed that in wild-type Col-0 ovules undergoing meiosis, AGO9 is localized in discrete cytoplasmic foci of sporophytic cells, preferentially in the apical region of the L1 layer, but not in meiotically dividing cells or in the functional megaspore. The same antibody was used to localize AGO9 in Stage 1 ovules of all five selected ecotypes (Figure 4). In premeiotic Stage 1 ovules of Col-0, Bor-4, and Sha-0, AGO9 was localized in cytoplasmic foci present in most sporophytic cells of the primordium, but also transiently in the nucleus of the MMC at variable expression levels. In these three ecotypes, most Stage 1 ovules also showed a clear pattern of preferential AGO9 localization in a cluster of apical L1 cells located at the distal pole of the MMC, in agreement with previous immunolocalizations conducted in Col-0 at subsequent developmental stages (Figures 4A to 4C). By contrast, most Stage 1 ovules of Mr-0 and Cvi-0 did not show this preferential localization of AGO9 in cells of the L1 layer (Figures 4D and 4E). Whereas the large majority of ovules of Col-0, Bor-4, and Sha-0 showed AGO9 localization in apical cells of the L1 layer (86.4% for Col-0, 97.2% for Bor-4, and 95.8% for Sha-0; total n = 119), only close to 50% showed the equivalent pattern in Mr-0 and Cvi-0 (50% for Cvi-0 and 53.4% for Mr-0; total n = 94). These results indicate that the ecotypic differences found in the pattern of AGO9 transcriptional regulation are also reflected in the cellular pattern of protein localization.

Figure 4.

AGO9 Protein Localization in Stage1 Ovules of Arabidopsis.

(A) AGO9 localization in a Col-0 ovule.

(B) AGO9 localization in a Sha-0 ovule.

(C) AGO9 localization in a Bor-4 ovule.

(D) Cvi-0 ovule showing absence of AGO9 localization in the L1 layer.

(E) Mr-0 ovule showing absence of AGO9 localization in the L1 layer.

(F) AGO9 localization in a heterozygous rdr6-15/+ ovule; arrows indicate the presence of gamete precursors.

(G) AGO9 localization in a Mr-0 ovule; arrows indicate the presence of gamete precursors.

(H) AGO9 localization in a Bor-4 ovule; arrows indicate the presence of gamete precursors.

(I) AGO9 localization in a Cvi-0 ovule; arrows indicate the presence of gamete precursors.

(J) AGO9 expression is absent in homozygous ago9-3 ovules.

L1, L1 cell layer; N, nucleus of the MMC. Bars = 10 μm in (A) to (J) and 5 μm in insets in (F) to (I).

Abnormal Ectopic Cells in Ovules Defective for RDR6 Share Identity with Ectopic Cells Found in the Analyzed Ecotypes

The nuclear pattern of AGO9 protein localization specifically shown by the MMC was also present in extranumerary cells found in ovules of ecotypes Mr-0, Bor-4, and Cvi-0. Previous studies indicated that heterozygous rdr6-15/+ individuals showed aberrant cell specification at premeiotic stages, with several female gamete precursors differentiating, growing, and dividing at the apical region of the developing ovule. To determine if the ectopic cells naturally found in selected ecotypes acquire a developmental identity similar to aberrant accessory cells found in ovules defective for RDR6, we conducted AGO9 whole-mount immunolocalizations in ovules of heterozygous rdr6-15/+ plants. Under whole-mount histological observations, the frequency at which Stage 1 rdr6-15/+ ovules exhibited accessory cells was of 31% (n = 538). For rdr6-15/+ ovules, whereas the preferential localization of AGO9 in the apical cells of the L1 layer was absent, AGO9 was expressed in the nucleus of accessory cells present in the nucellus (Figure 4F). Under confocal illumination, the frequency of Stage 1 rdr6-15/+ ovules showing AGO9 localization was of 26% (n = 33). An identical nuclear pattern of AGO9 localization was observed in Stage 1 ectopic cell configurations present in ovules of the Mr-0, Bor-4, and Cvi-0 ecotypes (Figures 4G to 4I), suggesting that naturally occurring ectopic cells in Arabidopsis ecotypes acquire the same identity as abnormal female gamete precursors found in rdr6-15/+ individuals, confirming that natural variation in the specification of female gamete precursors acts through some of the sRNA-dependent epigenetic pathways that prevail in the ovule of Arabidopsis.

DISCUSSION

Intraspecific natural variation in the angiosperms offers opportunities for natural selection to exert evolutionary pressure over the diversity of developmental pathways that are essential for survival, reproduction, or dispersal (Alonso-Blanco et al., 2009; Prasad et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2014). In some cases, this variation is directly related to quantitative traits that can be mapped and associated with developmental or physiological processes (Atwell et al., 2010; Strange et al., 2011), whereas in others it can be traced to functional multiallelic diversity of a single locus (Todesco et al., 2010). Epigenetic natural variation, manifested through either epimutations or epialleles, is currently under intense investigation to assess its impact in both adaptability and evolution. Although the extent to which epigenetic variation contributes to phenotypic variation remains to be determined, several examples of naturally occurring epialleles that affect plant development have been reported (Brink, 1956; Cubas et al., 1999; Manning et al. 2006). Arabidopsis has provided abundant evidence of epigenetic variation through either spontaneous or induced epimutants, including the induction of flowering, seed development, and genomic imprinting (Shindo et al., 2006; Fujimoto et al., 2011; Pignatta et al., 2014); however, the consequences of natural epigenetic variation in gametogenesis have not been investigated.

Our study shows that natural variation among distinct Arabidopsis ecotypes reflects the epigenetic mechanisms that lead to the differentiation of female gamete precursors at the onset of meiosis. Despite significant differences in their intrinsic frequencies of ectopic configurations, crosses between Col-0 and Sha-0 or Mr-0 showed additive effects, suggesting that widespread natural variation is based on conserved and independent genetic factors that control the specification of gamete precursors. By contrast, F1 hybrids between Col-0 and Bor-4 and Cvi-0 gave rise to ovules in which the frequency of gamete precursors was significantly increased compared with the corresponding mid-parent value. This disruption in the control of cell specification, beyond the frequency observed in the parental ecotypes, is reminiscent of nonadditive effects associated with the phenomenon of heterosis or hybrid vigor (Birchler et al., 2010; Chen, 2010). Differences in the phenotypic frequency of ectopic configurations are reminiscent of heterotic responses previously reported for F1 progeny of some Arabidopsis ecotypes (Moore and Lukens, 2011; Groszmann et al., 2014). A similar effect was also found in Medicago sativa, for which only certain parental combinations produced heterotic responses, as revealed by nonadditive gene expression (Li et al., 2009). Although an increase in the number of female gamete precursors does not necessarily affect fertility or seed production, the possibility of increasing the number of cells entering the gametophytic developmental pathway, through divergent allelic combinations present in specific ecotypic hybrids, could represent an adaptation to detrimental conditions that affect female meiosis and cause fertility defects.

Several studies have raised the possibility that alternative reproductive pathways, such as tetraspory or asexual reproduction through seeds (apomixis), evolved as a response to hybridization, genomic collisions, or unstable climatic environment (Carman, 1997; Voigt-Zielinski et al., 2012; Lovell et al., 2013; Hojsgaard et al., 2014). Segregating F2 populations of ecotypic crosses showed a continuous distribution of the frequency of ectopic configurations, suggesting that the genetic factors influencing the phenotype are quantitative and conserved among different ecotypes. In agreement with our results, these type of nonadditive effects are particularly evident in ecotypic hybrids or polyploid individuals that are often correlated with changes in gene expression (Chen, 2007; Miller et al., 2012; Chen, 2013), and large-scale transcriptional analysis in hybrids of Arabidopsis ecotypes indicate that nonadditive changes in gene expression result in alteration of developmental or physiological processes, including photosynthetic capacity, seedling development, or leaf morphology (Fujimoto et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012; Todesco et al., 2012; Chen, 2013).

In addition to genetically related natural variation, epigenetic variability can also contribute to the phenotypic differences found among Arabidopsis ecotypes (Latzel et al., 2013; Silveira et al., 2013; Cortijo et al., 2014). Our results show that ecotypic variation in cell differentiation is influenced by the functional activity of AGO9 and RDR6. Whereas AGO9 encodes an AGO protein that preferentially interacts with a 24-nucleotide sRNA corresponding to transposable elements located in the pericentromeric regions of all Arabidopsis chromosomes (Durán-Figueroa and Vielle-Calzada, 2010; Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010), RDR6 acts in the biogenesis of various types of sRNAs including trans-acting small interfering RNAs and in posttranscriptional transgene silencing mediated by sRNAs (Peragine et al., 2004; Yoshikawa et al., 2005; Chitwood et al., 2009). AGO9 is phylogenetically related to AGO4 and AGO6, proteins that are involved in heterochromatic silencing through the RNA-directed DNA methylation pathway (Zilberman et al., 2003, 2004; Vaucheret, 2008; Havecker et al., 2010; Mallory and Vaucheret, 2010; Eun et al., 2011). The introduction of a single dominant loss-of-function ago9 or rdr6 allele in some Arabidopsis ecotypes resulted in a buffering effect that limited the number of ovules showing ectopic configurations, whereas this buffering effect was lost in plants that completely lost AGO9 activity.

These results suggest that the partial loss of AGO9 activity is epigenetically sensed to restrict the number of sporophytic cells that premeiotically differentiate into female gamete precursors by AGO9- or RDR6-dependent mechanisms yet to be elucidated. This is also reflected in the comparison of the pattern of reporter gene expression that results from GUS fusions to a large 2619-bp genomic segment that represents the AGO9 regulatory region of either Col-0 or Mr-0. Variation in transcriptional regulation of AGO9 was observed when the AGO9 regulatory region present in the genome of Mr-0 was introduced into the Col-0 background, exposing the effects of accumulated genetic differences between these two ecotypes. Although the pattern of AGO9 mRNA localization is equivalent in both ecotypes, their initial pattern of transcriptional regulation is antagonistic, revealing that divergent allelic combinations can have an effect at the transcriptional level in the control of AGO9 expression. When comparing transcriptional fusions corresponding to Col-0 and Mr-0 alleles, the pattern of GUS expression is similar but not identical at the onset of female gametogenesis, suggesting that a dynamic pattern of transcriptional regulation and possibly mRNA transport prevails during megasporogenesis, since the pattern of mRNA localization coincides with the final pattern of AGO9 protein localization. Because AGO9 contains a large intron at the 5′ region that was not included in the proAGO9:GUS fusions tested, it is possible that additional genomic elements absent in our transgenic lines could influence the ecotypic pattern of AGO9 transcription. The transcriptional regulation of AGO9 is also altered in some hybrids between ecotypes, particularly in those exhibiting a nonadditive exacerbation of the frequency of ectopic configurations (Col-0 × Bor-4 and Col-0 × Cvi-0 F1 individuals), suggesting that hybridization can also perturb AGO9 expression by reducing its transcriptional activity, leading to the differentiation of accessory cells into premeiotic gamete precursors, leading to phenotypic consequences that result in natural variation during female reproductive development.

Previous results showed that during megasporogenesis, AGO9 protein localization was confined to discrete foci present in the cytoplasm of sporophytic cells within the nucellus, with abundant expression at the apex of the ovule primordium, in cells of the L1 layer (Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010). Our results show that the same pattern prevails in Stage 1 ovules at the onset of meiosis; however, the nucleus of the MMC in several ecotypes sporadically shows AGO9 expression, suggesting that an ephemeral and transient nuclear AGO9 localization can be found in the MMC, a discovery that suggest a dynamic pattern of protein traffic between cytoplasm and nucleus reminiscent of AGO4 dynamics in root cells (Li et al., 2006; Pontes et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2012). In the case of AGO9, nuclear localization is exclusive of the MMC and ectopic cells acquiring a gamete precursor identity in several ecotypes and individuals defective in RDR6, a result suggesting that ectopic cell configurations naturally exhibited by some Arabidopsis ecotypes share a developmental identity with ectopic gamete precursors found in ovules defective in the epigenetic control of cell specification. Further cytological and molecular studies will be necessary to integrate an understanding of AGO9 function, sRNA dynamics, and the early control of cell specification in the ovule.

Contrary to other cases in which specific ecotype combinations resulted in hybrids showing deleterious phenotypes (Todesco et al., 2010; Durand et al., 2012), no detrimental effects in fertility were found in ecotypic hybrids or AGO9-defective plants, suggesting that the phenotypic variation among ecotypes could be related to neutral accumulation of genetic differences or by episodes of natural selection that lead to fixation of certain genetic configurations (Atwell et al., 2010; Long et al., 2013). While several ecotypes and their hybrids exhibited variable frequencies of ectopic configurations, female gametophyte development occurred normally in all backgrounds, with a single meiotically derived cell differentiating into a functional megaspore, suggesting that in most cases ectopic cells degenerate without additional development. A similar pattern was observed in Sorghum bicolor, where the sporadic presence of aposporous initials correlated with an acceleration of meiotic initiation but no extranumerary female gametophytes were found at subsequent developmental stages (Carman et al., 2011). Our results favor the possibility of a flexible control of gamete precursor cell specification prevailing in Arabidopsis at the onset of meiosis, but a robust canalization mechanism acting at the onset of the processes that trigger meiosis and megagametogenesis; the molecular mechanisms that ensure the establishment of such a canalized developmental process could be partially dependent on the epigenetic pathways that involve AGO9 and RDR6. In several families of flowering plants, the number of female gamete precursors that can occur within a single ovule is highly variable, with extreme examples such as Peonia californica exhibiting up to 40 premeiotic precursors (Walters, 1962). Our results suggest that some of the epigenetic mechanisms that prevail during early ovule development are involved in the natural phenotypic variation observed during megasporogenesis. Future comparative studies of the role of genes such as AGO9 and RDR6 in species showing alternative gametophytic pathways will provide insights into the evolution of the epigenetic mechanisms that control female gametogenesis and cell specification in flowering plants.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes Bor-4, Sha-0, Cvi-0, and Mr-0 were obtained from the ABRC as part of the collection of 96 ecotypes provided by Joy Bergelson, Martin Kreitman, and Magnus Nordborg (Stock CS22660). Tetraploid Col-0 (CS3176) and Ler were a gift from David Galbraith (University of Arizona). ago9-3 (SAIL_34_G10) and rdr6-15 (SAIL_617_H07) were also obtained from the ABRC. Five rounds of backcrossing were performed to introgress the ago9-3 mutant allele into Bor-4 ecotype. All seeds were surface sterilized with 100% ethanol or with chlorine gas and germinated in Murashige and Skoog medium at 22°C or 25°C under stable long-day (16 h light/8 h dark) or full-day conditions. Plants were grown at 24°C under controlled growth chamber or greenhouse conditions.

Generation and Analysis of proAGO9:GUS Transformants

The regulatory region of the AGO9 gene (At5g21150) from Col-0 and Mr-0 ecotypes was transcriptionally fused to the uidA (GUS) reporter gene by amplifying a 2619-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the complete intergenic region located upstream of its coding sequence but excluding the 5′ untranslated region (primers: pAGO9S1_HindIII 5′-AATATTAAGCTTGGGAGACAGAAAGTGCGGTGAGAGAGAGAC-3′ and pAGO9AS1_KpnI 5′-GGCCTGGGTACCATTCACTAAAATATAGGTGTGTCGCTTATA-3′). Amplicons were cloned into pCR8 TOPO TA (Invitrogen) and used as donors in LR recombination (LR Clonase II; Invitrogen) with pMDC162 (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003), producing a binary vector that contains the uidA reporter gene. Transgenic Col-0 plants were obtained by floral dipping as previously described (Clough and Bent, 1998). At least 15 T1 individuals were obtained and analyzed for each of the two constructs (Col-0 or Mr-0 version). At least five individuals of 10 independent T2 transformants were cytologically examined to quantify the frequency of GUS expression at different stages of megasporogenesis.

Cytological and Histochemical Analysis

Inflorescences were fixed in FAA (50% ethanol, 10% formaldehyde, and 5% acetic acid) for 24 to 48 h and subsequently dehydrated in 70% ethanol. Immature flower buds were dissected with hypodermic needles (1-mL insulin syringes; TERUMO SS10M2913M) to isolate the developing gynoecia. Several hundred ovules for each of the four stages were obtained by mounting individual gynoecia in regular microscope slides and immersing in Herr’s clearing solution (phenol:chloral hydrate:85% lactic acid:xylene:clove oil in a 1:1:1:0.5:1 proportion). Histochemical localization of GUS activity was performed by incubating gynoecia of 0.5 to 1 mm in length in GUS staining solution (10 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, and 1 mg mL−1 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronic acid in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 2 to 36 h at 37°C. For propidium iodide staining, gynoecia of 0.5 to 0.7 mm in length were fixed in FPA (10% formaline, 5% propionic acid, and 70% ethanol) overnight at 4°C. After fixation, samples were washed with 100 mM l-arginine, pH 8.0 (Sigma-Aldrich) and stained with 2 mg mL−1 propidium iodide in 100 mM of l-Arg (pH 12). Ovule primordia were exposed by gently pressing a cover slip over a conventional slide containing 16 μL of Vectashield (VectorLabs). Serial optical sections were obtained on a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal laser scanning microscope, with single-track configuration for detecting propidium iodide (excitation with a diode-pumped solid-state laser at 568 nm, with emission collected using a band-pass of 575 to 615 nm). Sections were edited using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012). For light microscopy observations, samples were analyzed under Nomarski illumination using a DMR Leica microscope.

Whole-Mount in Situ Hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes specific for AGO9 were synthesized by in vitro transcription as previously described (Vielle-Calzada et al., 1999; Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010). Hybridizations were performed as previously described (García-Aguilar et al., 2005). Developing gynoecia of 0.5 to 0.8 mm in length were fixed in paraformaldehyde (4% paraformaldehyde, 2% Triton, and 1× PBS in diethylpyrocarbonate [DEPC]-treated water) for 2 h at room temperature with gentle agitation, washed three times in 1× PBS-DEPC water, and embedded in 15% acrylamide:bisacrylamide (29:1) using precharged slides (Fisher Probe-On) treated with poly-l-Lys as described (Bass et al., 1997). Gynoecia were gently opened to expose the ovules by pressing a cover slip on top of the acrylamide. Samples were then treated with 0.2 M HCl for 20 min at room temperature, followed by a washing step in 1× PBS-DEPC water. The slides were then incubated with proteinase K (1 μg mL−1) for 30 min at 37°C. The proteinase K reaction was stopped in glycine (2 mg mL−1). A postfixation step was performed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, followed by incubation in hybridization buffer (6× SSC buffer, 3% SDS, 50% formamide, and 0.1 mg mL−1 of yeast tRNA [Roche]) for 2 h at 55°C. An overnight incubation was performed using 600 ng of sense or antisense RNA probe against AGO9 in hybridization buffer. After overnight incubation, three washing steps with 0.2× SSC/0.1% SDS at 55°C were performed. Slides were treated with RNase (10 μg mL−1), washed four times in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS at 55°C, and treated with 1× TBS/0.5% blocking agent (Roche) for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were incubated with anti-DIG (Roche) at a concentration of 1:1000 in 1× TBS/1% BSA for 2 h at room temperature. After antibody incubation, four washing steps in 1× TBS/0.5% BSA/1% Triton X-100 were performed at room temperature. Slides were incubated in detection buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween, and 1 mM levamisole [Sigma-Aldrich]) for 15 min before adding 10 μL of each nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate (AP Conjugate Substrate Kit; Bio-Rad) per milliliter of detection buffer and incubated overnight at room temperature. Slides were mounted in 50% glycerol and visualized using Nomarski illumination under a Leica DRM microscope.

Whole-Mount Protein Immunolocalization

Developing gynoecia of 0.5 to 0.6 mm in length were fixed in paraformaldehyde (1× PBS, 4% paraformaldehyde, and 2% Triton), under continuous agitation for 2 h on ice, washed three times in 1× PBS, and embedded in 15% acrylamide:bisacrylamide (29:1) over precharged slides (Fisher Probe-On) treated with poly-l-Lys as described (Bass et al., 1997). Gynoecia were gently opened to expose ovules by pressing a cover slip on top of the acrylamide. Samples were digested in an enzymatic solution composed of 1% driselase, 0.5% cellulase, and 1% pectolyase (all from Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× PBS for 60 min at 37°C, subsequently rinsed three times in 1× PBS, and permeabilized for 2 h in 1× PBS:2% Triton. Blocking was performed with 1% BSA (Roche) for 1 h at 37°C. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with AGO9 primary antibody used at a dilution of 1:100 (Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010). Slides were washed for 8 h in 1× PBS:0.2% Triton, with refreshing of the solution every 2 h. The samples were then coated overnight at 4°C with secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) at a concentration of 1:300. After washing in 1× PBS:0.2% Triton for at least 8 h, the slides were incubated with propidium iodide (500 μg mL−1) in 1× PBS for 20 min, washed for 40 min in 1× PBS, and mounted in Prolong medium (Molecular Probes) overnight at 4°C. Serial sections on Stage 1 ovules were captured on a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META), with multitrack configuration for detecting iodide (excitation with a diode-pumped solid-state laser at 568 nm, emission collected using a band-pass of 575 to 615 nm) and Alexa 488 (excitation with an argon laser at 488 nm, emission collected using a band-pass of 500 to 550 nm). Laser intensity and gain were set at similar levels for all experiments. Projections of selected optical sections were generated using ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data for genes in this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL database or the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database under the following accession numbers: AGO9, NM_122122/AED92940 or At5g21150; and RDR6, NM_114810/AEE78550 or At3g49500. The ago9-3 (SAIL_34_G10) and rdr6-15 (SAIL_617_H07) lines were obtained from the ABRC.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. AGO9 mRNA localization in the developing ovule of Col-0 and Mr-0 ecotypes.

Supplemental Table 1. Quantitative analysis of ectopic configurations during megasporogenesis in selected ecotypes of Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Table 2. Quantitative analysis of ectopic configurations in the ovule of ecotypic F1 hybrids.

Supplemental Table 3. Segregation analysis in F2 populations from Arabidopsis ecotype hybrids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stewart Gillmor and Shai Lawit for useful comments on the article, Marcelina García-Aguilar for technical advice with immunolocalizations, and members of the Group of Reproductive Development and Apomixis for stimulating discussions. All Arabidopsis seed stocks were obtained through the ABRC at Ohio State University. D.R-L. and G.L-M. were recipients of a graduate scholarship from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT). Research was supported by CONACyT, the DuPont Pioneer regional initiatives to benefit local subsistence farmers, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.R.-L. and J.-P.V.-C. designed the research. D.R.-L. performed the genetic crosses and cytological analysis on all materials. D.R.-L. and G.L.-M. generated the transgenic lines and carried out whole-mount immunolocalizations and whole-mount in situ hybridizations. U.A.-V. contributed new histocytochemical tools. D.R.-L. and J.-P.V.-C. analyzed the results and wrote the article.

Glossary

- MMC

megaspore mother cell

- FM

functional megaspore

- sRNA

small RNA

- Col-0

Columbia-0

- Sha-0

Shakdara-0

- Bor-4

Borky-4

- Cvi-0

Cape Verde Islands-0

- Mr-0

Monterrosso-0

- Ler

Landsberg erecta

- DEPC

diethylpyrocarbonate

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alonso-Blanco C., Aarts M.G.M., Bentsink L., Keurentjes J.J.B., Reymond M., Vreugdenhil D., Koornneef M. (2009). What has natural variation taught us about plant development, physiology, and adaptation? Plant Cell 21: 1877–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.T., Wagner M.R., Rushworth C.A., Prasad K.V.S.K., Mitchell-Olds T. (2014). The evolution of quantitative traits in complex environments. Heredity (Edinb.) 112: 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta-Medina A., Demesa-Arévalo E., Vielle-Calzada J.P. (2011). Epigenetic control of cell specification during female gametogenesis. Sex. Plant Reprod. 24: 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwell S., et al. (2010). Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature 465: 627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelier J.B., Friedman W.E. (2011). Female gamete competition in an ancient angiosperm lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 12360–12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass H.W., Marshall W.F., Sedat J.W., Agard D.A., Cande W.Z. (1997). Telomeres cluster de novo before the initiation of synapsis: a three-dimensional spatial analysis of telomere positions before and during meiotic prophase. J. Cell Biol. 137: 5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler J.A., Yao H., Chudalayandi S., Vaiman D., Veitia R.A. (2010). Heterosis. Plant Cell 22: 2105–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretagnolle F., Thompson J.B. (1995). Gametes with the somatic chromosome number: mechanisms of their formation and role in the evolution of autopolyploid plants. New Phytol. 129: 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink R.A. (1956). A genetic change associated with the R Locus in maize which is directed and potentially reversible. Genetics 41: 872–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman J.G. (1997). Asynchronous expression of duplicate genes in angiosperms may cause apomixis, bispory, tetraspory, and polyembryony. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 61: 51–94. [Google Scholar]

- Carman J.G., Jamison M., Elliott E., Dwivedi K.K., Naumova T.N. (2011). Apospory appears to accelerate onset of meiosis and sexual embryo sac formation in sorghum ovules. BMC Plant Biol. 11: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.J. (2007). Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58: 377–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.J. (2010). Molecular mechanisms of polyploidy and hybrid vigor. Trends Plant Sci. 15: 57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.J. (2013). Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14: 471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood D.H., Nogueira F.T., Howell M.D., Montgomery T.A., Carrington J.C., Timmermans M.C. (2009). Pattern formation via small RNA mobility. Genes Dev. 23: 549–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortijo S., et al. (2014). Mapping the epigenetic basis of complex traits. Science 343: 1145–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubas P., Vincent C., Coen E. (1999). An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature 401: 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M.D., Grossniklaus U. (2003). A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133: 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews G.N., Koltunow A.M. (2011). The female gametophyte. The Arabidopsis Book. 9: e0155, doi/10.1199/tab.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Figueroa N., Vielle-Calzada J.P. (2010). ARGONAUTE9-dependent silencing of transposable elements in pericentromeric regions of Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 5: 1476–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand S., Bouché N., Perez Strand E., Loudet O., Camilleri C. (2012). Rapid establishment of genetic incompatibility through natural epigenetic variation. Curr. Biol. 22: 326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames A.J. (1961). Morphology of the Angiosperms. (New York: McGraw-Hill; ). [Google Scholar]

- Eun C., Lorkovic Z.J., Naumann U., Long Q., Havecker E.R., Simon S.A., Meyers B.C., Matzke A.J., Matzke M. (2011). AGO6 functions in RNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing in shoot and root meristems in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 6: e25730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrándiz C., Pelaz S., Yanofsky M.F. (1999). Control of carpel and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68: 321–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto R., Taylor J.M., Shirasawa S., Peacock W.J., Dennis E.S. (2012). Heterosis of Arabidopsis hybrids between C24 and Col is associated with increased photosynthesis capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 7109–7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto R., Sasaki T., Kudoh H., Taylor J.M., Kakutani T., Dennis E.S. (2011). Epigenetic variation in the FWA gene within the genus Arabidopsis. Plant J. 66: 831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Aguilar M., Michaud C., Leblanc O., Grimanelli D. (2010). Inactivation of a DNA methylation pathway in maize reproductive organs results in apomixis-like phenotypes. Plant Cell 22: 3249–3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Aguilar M., Dorantes-Acosta A., Pérez-España V., Vielle-Calzada J.-P. (2005). Whole-mount in situ mRNA localization in developing ovules and seeds of Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 23: 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M., Zamore P.D. (2009). Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 94–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimanelli D., Leblanc O., Perotti E., Grossniklaus U. (2001). Developmental genetics of gametophytic apomixis. Trends Genet. 17: 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus U., Schneitz K. (1998). The molecular and genetic basis of ovule and megagametophyte development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 9: 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M., Gonzalez-Bayon R., Greaves I.K., Wang L., Huen A.K., Peacock W.J., Dennis E.S. (2014). Intraspecific Arabidopsis hybrids show different patterns of heterosis despite the close relatedness of the parental genomes. Plant Physiol. 166: 265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havecker E.R., Wallbridge L.M., Hardcastle T.J., Bush M.S., Kelly K.A., Dunn R.M., Schwach F., Doonan J.H., Baulcombe D.C. (2010). The Arabidopsis RNA-directed DNA methylation argonautes functionally diverge based on their expression and interaction with target loci. Plant Cell 22: 321–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojsgaard D., Greilhuber J., Pellino M., Paun O., Sharbel T.F., Hörandl E. (2014). Emergence of apospory and bypass of meiosis via apomixis after sexual hybridisation and polyploidisation. New Phytol. 204: 1000–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B.-Q., Russell S.D. (1992). Female germ unit: Organization, isolation, and function. Int. Rev. Cytol. 140: 233–293. [Google Scholar]

- Karpechenko G.D. (1927). The production of polyploid gametes in hybrids. Hereditas 9: 349–368. [Google Scholar]

- Koltunow A.M., Grossniklaus U. (2003). Apomixis: a developmental perspective. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54: 547–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzel V., Allan E., Bortolini Silveira A., Colot V., Fischer M., Bossdorf O. (2013). Epigenetic diversity increases the productivity and stability of plant populations. Nat. Commun. 4: 2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.F., Pontes O., El-Shami M., Henderson I.R., Bernatavichute Y.V., Chan S.W., Lagrange T., Pikaard C.S., Jacobsen S.E. (2006). An ARGONAUTE4-containing nuclear processing center colocalized with Cajal bodies in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 126: 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wei Y., Nettleton D., Brummer E.C. (2009). Comparative gene expression profiles between heterotic and non-heterotic hybrids of tetraploid Medicago sativa. BMC Plant Biol. 9: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber D., Lora J., Schrempp S., Lenhard M., Laux T. (2011). Arabidopsis WIH1 and WIH2 genes act in the transition from somatic to reproductive cell fate. Curr. Biol. 21: 1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Q., et al. (2013). Massive genomic variation and strong selection in Arabidopsis thaliana lines from Sweden. Nat. Genet. 45: 884–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell J.T., Aliyu O.M., Mau M., Schranz M.E., Koch M., Kiefer C., Song B.H., Mitchell-Olds T., Sharbel T.F. (2013). On the origin and evolution of apomixis in Boechera. Plant Reprod. 26: 309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid E.N., Friedman W.E. (2009). The developmental basis of an evolutionary diversification of female gametophyte structure in Piper and Piperaceae. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 103: 869–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari P. (1950). An Introduction to the Embryology of Angiosperms. (New York: MacGraw-Hill; ). [Google Scholar]

- Mallory A., Vaucheret H. (2010). Form, function, and regulation of ARGONAUTE proteins. Plant Cell 22: 3879–3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning K., Tör M., Poole M., Hong Y., Thompson A.J., King G.J., Giovannoni J.J., Seymour G.B. (2006). A naturally occurring epigenetic mutation in a gene encoding an SBP-box transcription factor inhibits tomato fruit ripening. Nat. Genet. 38: 948–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R.C., et al. (2012). Heterosis manifestation during early Arabidopsis seedling development is characterized by intermediate gene expression and enhanced metabolic activity in the hybrids. Plant J. 71: 669–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M., Zhang, C., and Chen, Z.J. (2012). Ploidy and hybridity effects on growth vigor and gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana hybrids and their parents. G3 (Bethesda) 2: 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moore, S., and Lukens, L. (2011). An evaluation of Arabidopsis thaliana hybrid traits and their genetic control. G3 1: 571–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nonomura K., Miyoshi K., Eiguchi M., Suzuki T., Miyao A., Hirochika H., Kurata N. (2003). The MSP1 gene is necessary to restrict the number of cells entering into male and female sporogenesis and to initiate anther wall formation in rice. Plant Cell 15: 1728–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura K., Morohoshi A., Nakano M., Eiguchi M., Miyao A., Hirochika H., Kurata N. (2007). A germ cell specific gene of the ARGONAUTE family is essential for the progression of premeiotic mitosis and meiosis during sporogenesis in rice. Plant Cell 19: 2583–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordborg M., et al. (2005). The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol. 3: e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo-Monfil V., Durán-Figueroa N., Arteaga-Vázquez M., Demesa-Arévalo E., Autran D., Grimanelli D., Slotkin R.K., Martienssen R.A., Vielle-Calzada J.P. (2010). Control of female gamete formation by a small RNA pathway in Arabidopsis. Nature 464: 628–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A., Yoshikawa M., Wu G., Albrecht H.L., Poethig R.S. (2004). SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 18: 2368–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatta D., Erdmann R.M., Scheer E., Picard C.L., Bell G.W., Gehring M. (2014). Natural epigenetic polymorphisms lead to intraspecific variation in Arabidopsis gene imprinting. eLife 3: e03198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes O., Li C.F., Costa Nunes P., Haag J., Ream T., Vitins A., Jacobsen S.E., Pikaard C.S. (2006). The Arabidopsis chromatin-modifying nuclear siRNA pathway involves a nucleolar RNA processing center. Cell 126: 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K.V.S.K., et al. (2012). A gain-of-function polymorphism controlling complex traits and fitness in nature. Science 337: 1081–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J., Schemske D.W. (1998). Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29: 467–501. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser L., Fischer R.L. (1993). The ovule and the embryo sac. Plant Cell 5: 1291–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Leal D., Vielle-Calzada J.P. (2012). Regulation of apomixis: learning from sexual experience. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15: 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefthaler U., Balasubramanian S., Sieber P., Chevalier D., Wisman E., Schneitz K. (1999). Molecular analysis of NOZZLE, a gene involved in pattern formation and early sporogenesis during sex organ development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 11664–11669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A., Wuest S.E., Vijverberg K., Baroux C., Kleen D., Grossniklaus U. (2011). Transcriptome analysis of the Arabidopsis megaspore mother cell uncovers the importance of RNA helicases for plant germline development. PLoS Biol. 9: e1001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9: 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneitz K., Hülskamp M., Pruitt R.E. (1995). Wild-type ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana: a light microscope study of cleared whole-mount tissue. Plant J. 7: 731–749. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan W.F., Avalkina N.A., Shamrov I.I., Batygina T.B., Golubovskaya I.N. (1996). The mac1 gene: controlling the commitment to the meiotic pathway in maize. Genetics 142: 1009–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo C., Lister C., Crevillen P., Nordborg M., Dean C. (2006). Variation in the epigenetic silencing of FLC contributes to natural variation in Arabidopsis vernalization response. Genes Dev. 20: 3079–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira A.B., Trontin C., Cortijo S., Barau J., Del Bem L.E., Loudet O., Colot V., Vincentz M. (2013). Extensive natural epigenetic variation at a de novo originated gene. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange A., Li P., Lister C., Anderson J., Warthmann N., Shindo C., Irwin J., Nordborg M., Dean C. (2011). Major-effect alleles at relatively few loci underlie distinct vernalization and flowering variation in Arabidopsis accessions. PLoS ONE 6: e19949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todesco M., et al. (2010). Natural allelic variation underlying a major fitness trade-off in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 465: 632–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todesco M., Balasubramanian S., Cao J., Ott F., Sureshkumar S., Schneeberger K., Meyer R.C., Altmann T., Weigel D. (2012). Natural variation in biogenesis efficiency of individual Arabidopsis thaliana microRNAs. Curr. Biol. 22: 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M.R., Okada T., Hu Y., Scholefield A., Taylor J.M., Koltunow A.M. (2012). Somatic small RNA pathways promote the mitotic events of megagametogenesis during female reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Development 139: 1399–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandendries R. (1909). Contribution á l'histoire du développement des crucifères. Cellule 25: 412–429. [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H. (2008). Plant ARGONAUTES. Trends Plant Sci. 13: 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vielle-Calzada J.-P., Thomas J., Spillane C., Coluccio A., Hoeppner M.A., Grossniklaus U. (1999). Maintenance of genomic imprinting at the Arabidopsis medea locus requires zygotic DDM1 activity. Genes Dev. 13: 2971–2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt-Zielinski M.L., Piwczyński M., Sharbel T.F. (2012). Differential effects of polyploidy and diploidy on fitness of apomictic Boechera. Sex. Plant Reprod. 25: 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters J.L. (1962). Megasporogenesis and gametophyte selection in Paeonia californica. Am. J. Bot. 49: 787–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ye R., Wang W., Iki T., Liu C., Wu Y., Ishikawa M., Zhou X., Qi Y. (2012). Cytoplasmic assembly and selective nuclear import of Arabidopsis Argonaute4/siRNA complexes. Mol. Cell 46: 859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M., Peragine A., Park M.Y., Poethig R.S. (2005). A pathway for the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 19: 2164–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman D., Cao X., Jacobsen S.E. (2003). ARGONAUTE4 control of locus-specific siRNA accumulation and DNA and histone methylation. Science 299: 716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman D., Cao X., Johansen L.K., Xie Z., Carrington J.C., Jacobsen S.E. (2004). Role of Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE4 in RNA-directed DNA methylation triggered by inverted repeats. Curr. Biol. 14: 1214–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.