Abstract

Background/Purpose

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) arises in pediatric/adolescent patients without cirrhosis. We retrospectively evaluated the impact of resection, nodal status, metastasis, and PRETEXT stage on overall survival (OS).

Methods

With IRB approval, we reviewed records of 25 consecutive pediatric patients with FL-HCC treated at our institution from 1981–2011. We evaluated associations between OS and PRETEXT stage, nodal involvement, metastasis, and complete resection.

Results

Median age at diagnosis was 17.1 years (range, 11.6–20.5). Median follow-up was 2.74 years (range, 5–9.5). Five (28%) patients had PRETEXT stage 1 disease, 10 (56%) had stage 2, 2 (11%) had stage 3, and 2 (11%) had stage 4 disease. On presentation, 17 (68%) patients had N1 disease, and 7 (28%) had parenchymal metastases. Complete resection was achieved in 17 (80.9%) of 21 patients who underwent resection. Five-year OS was 42.6%. Survival was positively associated with complete resection (P=0.003), negative regional lymph nodes (P=0.044), and lower PRETEXT stage (P<0.001), with a trend for metastatic disease (P=0.05).

Conclusions

In young patients with FL-HCC, lower PRETEXT stage and complete resection correlated with prolonged survival, while metastatic disease and positive lymph node status was associated with poor prognosis. Thus, we recommend complete resection and regional lymphadenectomy whenever possible.

Keywords: fibrolamellar, hepatocellular carcinoma, pediatric, adolescent, prognostic

Introduction

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is a rare liver malignancy that arises in young people without a history of cirrhosis or viral hepatitis. It often presents with nonspecific symptoms and at an advanced stage. Currently, there are no effective treatments for metastatic disease. For regional disease, surgical resection remains the cornerstone of therapy. Some progress has been made by cooperative group studies (e.g. SIOPEL), which have gathered sufficiently large cohorts for appropriate analysis of prognostic factors[1]. However, analyses regarding patient prognoses and survival for this variant of traditional hepatocellular carcinoma have been inconclusive. To identify the most relevant prognostic factors for overall survival, we conducted a retrospective review of our institution’s experience with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in patients younger than 22 years.

Patients and Methods

With institutional review board approval, we identified patients with FL-HCC who received care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between December 1981 and June 2011. Patient records were reviewed for demographic data, disease characteristics, surgical outcomes and follow-up. Pathology specimens were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis of FL-HCC. Attending radiologist assessments of pre-surgical radiology were used to determine Pretreatment Extent of Disease (PRETEXT) staging and tumor dimensions[2,3]. Elevated alpha-fetoprotein was defined as >20 ng/mL.

The log-rank test was used to determine significant associations between PRETEXT stage, nodal involvement, and complete (R0) resection status. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method in SPSS statistical software (version 20.0; IBM Inc, Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 25 consecutive patients with FL-HCC, with a median age at diagnosis of 17.1 years (range, 11.6–20.5 years). Fourteen females and 11 males were identified, a ratio of approximately 1.3 to 1. The most common presenting symptom was pain (n=18; 72%), followed by abdominal distention/mass (n=11; 44%), anorexia/nausea (n=8; 32%), and fever and jaundice (n=5; 20%). One patient with jaundice presented with acute cholangitis, and one patient required percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy prior to chemotherapy. Two patients presented with amenorrhea, and none of the patients presented with precocious puberty. One patient’s mother had undergone in vitro fertilization using exogenous estrogen. None of the patients had viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, or a family history of primary hepatobiliary malignancy. An elevated alpha-fetoprotein was present in 2 (2.3%) patients (22 and 33 IU/mL).

Nineteen (76%) patients had sufficient imaging data for PRETEXT staging. PRETEXT stage distribution was as follows: 5 (26%) patients with stage 1, 10 (53%) patients with stage 2, 2 (10.5%) with stage 3, and 2 (10.5%) with stage 4. Based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition, there were 5 (20%) patients with AJCC stage I disease, 1 (4%) patient with stage II, 1 (4%) with stage III, and 18 (72%) patients with stage IV (11 IVA and 7 IVB). Tumors arose in the left lobe in 12 (48%), in the right lobe in 7 (28%), and 6 (24%) were central or had bilateral involvement (segments 4&5 or 4&8). The median tumor size on preoperative imaging was 11 cm (range 4.2–13.6). Seventeen patients (68%) had positive regional lymph nodes and 7 (28%) had distant parenchymal metastases at diagnosis.

Treatment

Thirteen (52%) patients received chemotherapy, 3 as neoadjuvant, 8 as adjuvant, and 2 as their sole treatment. An additional 5 (20%) patients received radiotherapy, administered as neoadjuvant therapy in 1 patient, as adjuvant therapy in 2, as the sole treatment in 1 patient, and as intraoperative therapy in 1. Patients who received adjuvant therapy all had local invasion (vascular or adjacent organs), nodal disease or parenchymal metastases. The patient who received intraoperative radiation therapy had 10 Gray of direct therapy to retrocardiac lymph nodes.

Twenty-one (84%) patients underwent resection for cure, while four patients received biopsy and nonsurgical therapy as their primary treatment. Eight (32%) patients underwent a left lobectomy, 4 (16%) had a right lobectomy, 5 (20%) had a left trisegmentectomy, and 4 (16%) had a right trisegmentectomy. There were no intraoperative deaths.

Among the 21 patients who underwent resection for cure, a complete (R0) resection was achieved in 17 (80.9%) patients, R1 in 2 (9.5%), and R2 in 2 (9.5%). Information about vascular invasion was included in 19 pathology reports, and vascular invasion was evident in 12 (63.2%) of those patients. The median largest tumor dimension, as documented on pathology reports, was 10.5 cm (range 3.5–18). There were no patients with cirrhosis or evidence of intrinsic liver disease.

Median length of hospital stay was 8 days (range 5–14). Postoperative complications included four wound infections and one pulmonary embolus. Four patients were given total parenteral nutrition. The median length of follow-up for the entire cohort was 32.9 months (range 5.3–113.5). The median follow-up for surviving patients was 52.9 months (range 5.3–113.5).

Outcome

The 5-year rate of survival for the entire cohort was 42.6% (95% CI, 20–65.2) (Figure 1). The 5-year rate of survival for the patients undergoing resection was 51.6% (95% CI, 26–77.2). Twelve patients had local recurrence in the group with R0 and R1 margin status, with a median disease free survival of 15.6 months (range 4.3–56.6). Treatment of the recurrences consisted of re-resection in 4, resection with chemoradiation in 5, chemotherapy only in 2, hepatic artery embolization in 1, and hepatic artery embolization with Sho-saiko-to (an herbal supplement that may reduce fibrosis and hepatocyte proliferation[9]) in 1. At the time of analysis, 8 (66.7%) patients with a local recurrence had died, while four survivors were alive at 2.96, 7.2, 9.3 and 9.5 years after initial resection.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the overall survival rate for the entire cohort. Censored data points reflect the time that a patient was last seen; there were no known deaths during the study period.

Univariate Analysis

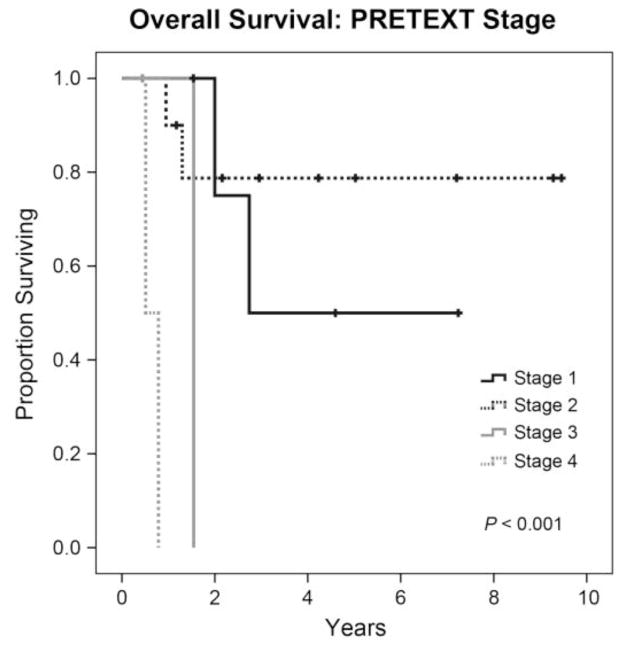

Variables that were found to be significantly associated with prolonged overall survival were R0 resection (P = 0.003) (Figure 2), lower PRETEXT stage (P < 0.001) (Figure 3) and negatively associated with positive regional lymph nodes (P = 0.044) (Figure 4). There was a trend for decreased survival time with positive distant metastatic disease (P = 0.05). See Table 1 for the specific distribution of patients.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the overall survival rate by resection margin status. R0 = complete resection, R1 = microscopically positive margins, R2 = gross residual disease; all patients were alive at last follow-up.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the overall survival rate by PRETEXT stage.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the overall survival rate by regional lymph node status. N0 = negative regional lymph node involvement, N1 = positive regional lymph node involvement.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Disease Factors Associated With Prolonged Survival

| Variable | Survivors | Mortalities | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower PRETEXT Stage | <0.001 | ||

| I | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | |

| II | 8 (80%) | 2 (20%) | |

| III | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | |

| IV | 0 | 2 (100%) | |

| Negative Resection Margins | 0.003 | ||

| Complete (R0) | 6 (35%) | 11 (65%) | |

| Microscopically positive (R1) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Gross residual disease (R2) | 0 | 6 (100%)* | |

| Regional Lymph Node Involvement | 0.044 | ||

| Negative | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Positive | 5 (29%) | 12 (71%) | |

| Distant Metastatic Disease | 0.05 | ||

| Negative | 10 (55.6%) | 8 (44.4%) | |

| Positive | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) |

For resection margins, 4 of the patients classified as R2 underwent biopsy only without resection.

Discussion

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma occurs at a rate of 0.2 per 100,000 population[4]. Despite its low incidence, it is an important primary liver tumor because it arises in young persons without any history of cirrhosis or viral hepatitis. Originally described by Edmondson in 1956 as a rare variant of traditional HCC, papers detailing clinical experience were not available until the 1980s[5]. Currently, it is being investigated by multinational cooperative groups, in series of small cohorts, and in population based reviews. Investigation of prognostic factors and the underlying biology of this rare tumor is hindered by epidemiological databases that lack comorbidities and adjuvant treatments, small series with variable treatment cohorts (especially for chemotherapy), and disparate outcome analyses relative to traditional HCC. Here, we define significant prognostic factors in the largest single-institution cohort of pediatric and adolescent patients with FL-HCC published to date. We focused our analysis on local factors in a cohort treated largely by surgical resection; we identified lower PRETEXT stage and negative resection margins to be positively associated with prolonged overall survival, while regional lymph node involvement and positive distant metastatic disease were negatively associated.

In our cohort, the median age was 17.1 years and the female-to-male ratio was 1.3 to 1. A preponderance of females among patients with FL-HCC has been noted in other studies, which is in contrast to the male predominance in previously published analyses of traditional HCC[4,6–8]. There were no patients with viral hepatitis, similar to other studies of FL-HCC in Western and European countries. In our cohort, 52% of patients received chemotherapy, including various protocols over 30 years as well as the use of alternative therapy, such as Sho-saiko-to[9]. The advances in downstaging unresectable hepatoblastoma with platinum-based chemotherapy have not proven effective in FL-HCC, and there was no increase in survival over time with newer or experimental protocols. A recent review by Kaseb et al. that assessed standardized chemotherapy protocols showed an improvement in overall survival with adjuvant and neoadjuvant regimens using 5-fluorouracil with interferon[10]. This analysis was not specific to pediatric patients, but provides a basis for possible implementation in pediatric patients. The results of an MSKCC trial using combinations of everolimus, leuprolide, and letrozole are forthcoming; however, the study was conducted in patients with unresectable FL-HCC.

Focusing on a surgically treated population, we identified negative surgical margins to be significantly associated with prolonged overall survival. Negative surgical margins were achieved in 84% of patients undergoing resection. Other series have contributed valuable information supporting the importance of surgical resection; however, many lacked the distinction between gross resection and microscopically negative margins. A recent review of SIOPEL data did not show a significant difference in survival between FL-HCC and traditional HCC[1]. However, only 17 (71%) of 24 of patients with FL-HCC underwent any type of resection, making direct comparisons difficult.

Positive regional lymph nodes were negatively associated with survival in our series. There are strong supporting data from several series regarding the higher incidence of regional lymph node involvement, higher rate of lymphadenectomy in FL-HCC, and worse prognosis of those with regional disease vs localized disease[11–15]. Furthermore, the high rate of regional recurrence in patients with node-positive FL-HCC warrants meticulous regional lymph node dissection[11,16,17]. In a parallel study of the genomics of FL-HCC, we found an active chimeric protein kinase in the primary tumors as well as all regional lymph nodes sequenced[18]. Thus, a regional lymphadenectomy is warranted, as this putative driver mutation was found in regional lymph nodes and represents a potential source of recurrence.

Metastatic disease was associated with decreased overall survival. The relative resistance of FL-HCC to chemotherapy likely contributes to poor outcomes in patients presenting with metastases. At the time of analysis there was one long-term survivor who had presented with metastatic disease who was disease free at 9.5 years post diagnosis. This patient had a large retroperitoneal mass that was resected, and a retrocardiac mass treated with resection and intraoperative radiation therapy. Similar to other analyses, PRETEXT staging was found to be significant and useful for prognosis[3]. A multivariate analysis to assess for the independence of resection margins from PRETEXT stage (smaller tumors being more resectable) would have been underpowered in this study.

The relative rarity of FL-HCC makes data collection and protocol design difficult, warranting continued investigation by multi-institutional and multinational cooperative groups. While chemotherapy has not proven effective as a primary or downstaging treatment, the recent discovery of a chimeric protein kinase in a small cohort of FL-HCC patients may provide therapeutic options or serum-based diagnosis[18]. While relatively rare, FL-HCC often presents at late stage, and patients with metastatic disease have a poor prognosis. Cooperative studies to gather detailed clinical information and tissue samples are of great importance to achieve further advances in treatment. Currently, surgical resection remains the cornerstone of therapy for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, and reasonable attempts for negative surgical margins with meticulous lymph node dissection are warranted.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weeda VB, Murawski M, McCabe AJ, Maibach R, Brugières L, Roebuck D, et al. Fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma does not have a better survival than conventional hepatocellular carcinoma-- Results and treatment recommendations from the Childhood Liver Tumour Strategy Group (SIOPEL) experience. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKinlay GA, Pritchard J. A common language for childhood liver tumours. Pediatr Surg Int. 1992;7:325–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roebuck DJ, Aronson D, Clapuyt P, Czauderna P, de Ville de Goyet J, Gauthier F, et al. 2005 PRETEXT: a revised staging system for primary malignant liver tumours of childhood developed by the SIOPEL group. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:123–32. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Is Fibrolamellar Carcinoma Different from Hepatocellular Carcinoma? A US Population-Based Study. Hepatology. 2004;39:798–803. doi: 10.1002/hep.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edmondson HA. Differential diagnosis of tumors and tumor-like lesions of liver in infancy and childhood. AMA J Dis Child. 1956;91:168–86. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1956.02060020170015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig JR, Peters RL, Edmondson HA, Omata M. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: A tumor of adolescents and young adults with distinctive clinico-pathologic features. Cancer. 1980;46:372–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800715)46:2<372::aid-cncr2820460227>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu S-B, Kim H-Y, Eo H, Won J-K, Jung S-E, Park K-W, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of pediatric hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2006;30:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7965-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czauderna P, Mackinlay G, Perilongo G, Brown J, Shafford E, Aronson D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: results of the first prospective study of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2798–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J-K, Kim J-H, Shin HK. Therapeutic effects of the oriental herbal medicine Sho-saiko-to on liver cirrhosis and carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:825–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaseb AO, Shama M, Sahin IH, Nooka A, Hassabo HM, Vauthey JN, et al. Prognostic Indicators and Treatment Outcome in 94 Cases of Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncology. 2013;85:197–203. doi: 10.1159/000354698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stipa F, Yoon SS, Liau KH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, et al. Outcome of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1331–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayo SC, Mavros MN, Nathan H, Cosgrove D, Herman JM, Kamel I, et al. Treatment and prognosis of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a national perspective. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torbenson M. Review of the clinicopathologic features of fibrolamellar carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:217–23. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3180504913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakar S, Burgart LJ, Batts KP, Garcia J, Jain D, Ferrell LD. Clinicopathologic features and survival in fibrolamellar carcinoma: comparison with conventional hepatocellular carcinoma with and without cirrhosis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1417–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ang CS, Kelley RK, Choti MA, Cosgrove DP, Chou JF, Klimstra D, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma: data from the fibrolamellar carcinoma consortium. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2013;6:3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malouf GG, Brugieres L, Le Deley M-C, Faivre S, Fabre M, Paradis V, et al. Pure and mixed fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas differ in natural history and prognosis after complete surgical resection. Cancer. 2012;118:4981–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAteer JP1, Goldin AB, Healey PJ, Gow KW. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: epidemiology and the impact of regional lymphadenectomy on surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:2194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honeyman JN, Simon EP, Robine N, Chiaroni-Clarke R, Darcy DG, Lim IIP, et al. Detection of a recurrent DNAJB1-PRKACA chimeric transcript in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2014;343:1010–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1249484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]