Abstract

Background

Engagement in HIV care helps to maximize viral suppression, which, in turn, reduces morbidity and mortality and prevents further HIV transmission. With more HIV cases than any other US city, New York City reported in 2012 that only 41% of all persons estimated to be living with HIV (PLWH) had a suppressed viral load, while nearly three-quarters of those in clinical care achieved viral suppression. Thus, retaining PLWH in HIV care addresses this central goal of both the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy and Governor Cuomo's plan to end the AIDS epidemic in New York State.

Methods

We conducted 80 in-depth qualitative interviews with PLWH in four NYC populations that were identified as being inconsistently engaged in HIV medical care: African immigrants, previously incarcerated adults, transgender women, and young men who have sex with men.

Results

Barriers to and facilitators of HIV care engagement fell into three domains: (1) system factors (e.g., patient-provider relationship, social service agencies, transitions between penal system and community); (2) social factors (e.g., family and other social support; stigma related to HIV, substance use, sexual orientation, gender identity, and incarceration); and (3) individual factors (e.g., mental illness, substance use, resilience). Similarities and differences in these themes across the four populations as well as research and public health implications were identified.

Conclusions

Engagement in care is maximized when the social challenges confronted by vulnerable groups are addressed; patient-provider communication is strong; and coordinated services are available, including housing, mental health and substance use treatment, and peer navigation.

Keywords: HIV care engagement, African immigrants, previously incarcerated adults, young men who have sex with men, transgender women

INTRODUCTION

Consistent engagement in HIV primary care (“HIV care”) can improve health and reduce morbidity, mortality, and onward HIV transmission by decreasing HIV viral load.1-6 Although much research focuses on the beginning (initial testing, linkage) and end (ART adherence, viral suppression) of the HIV care continuum, less is known about the key intermediate step – consistent engagement in care.7

Both the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy8 and Governor Cuomo's three-point plan to end the AIDS epidemic in New York State (NYS)9 prioritize retention of HIV-positive persons in health care, with viral suppression as a key goal. In 2012, only 41% of persons estimated to be infected with HIV in NYC were reported to have a suppressed viral load. However, of the 74,723 persons living with HIV/AIDS and under clinical monitoring in NYC in that year, almost three-quarters had an undetectable viral load. Clearly, to meet the goal of sustained viral suppression, more persons living with HIV need to be engaged in continuous HIV care. 10

The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) has identified four groups of people living with HIV (PLWH) in NYC as particularly vulnerable to suboptimal engagement in HIV care: African immigrants, recently released prisoners, young men who have sex with men (YMSM), and transgender women (TGW). In the limited research on HIV care engagement in these groups, studies have shown that HIV-positive African immigrants delay initiation of care,11 perhaps due to stigma, immigration-related barriers, and lack of health insurance.12 Other studies have found that previously incarcerated PLWH released into the community have poor virological and immunological outcomes,13 with low CD4+ cell counts and high viral loads.14 Delays in care engagement among recently released HIV-positive prisoners have been attributed to insecure housing, unemployment, fragmented social ties, substance abuse, and mental illness.15 Among HIV-positive YMSM of color, younger age (<21 years), history of depression, receiving program services, and feeling respected at the clinic were associated with improved retention in HIV care; having a CD4+ count <200 at baseline and being Latino were associated with poorer retention.16 One study of TGW documented stigma and concerns about interactions between hormone therapy and ARVs as challenges to HIV care engagement, whereas access to hormone therapy from an HIV provider was a facilitator.17

Although the literature documents a wide range of barriers to and facilitators of HIV care engagement, there is less qualitative research providing an in-depth understanding of issues of particular relevance to populations at high risk for inconsistent HIV care engagement in NYC. We rarely hear from the patients themselves, in their own words, what motivates or hinders them from seeking care or staying in care. To address this gap, we conducted a qualitative study exploring system, social, and individual barriers to and facilitators of engagement in HIV care among HIV-positive African immigrants, previously incarcerated adults, YMSM, and TGW. The resulting nuanced understanding may contribute to the development of effective service models to optimize HIV care engagement in New York City and other geographic locations where HIV-infected individuals in these demographic groups reside.

METHODS

This study was a collaboration among the Einstein-Montefiore Center for AIDS Research (E-M CFAR), the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Research at the NYS Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (HIV Center), and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH).

Eligibility and Recruitment

Eligibility criteria (based on self-report) for all four populations were (1) HIV-positive, (2) ≥ 3 months post-HIV diagnosis, (3) ≥18 years of age, and (4) having been linked to care (defined as at least one visit with an HIV provider). Group-specific eligibility criteria were, for previously incarcerated, released from jail or prison within the previous year; for African immigrants, born in Africa; for YMSM, 18-29 years old and self-identifying as a gay man or MSM; and, for TGW, self-identifying as a transgender woman. Convenience samples were recruited through community-based organizations, the Internet, and word-of-mouth referrals.

Procedures

We conducted one-hour, face-to-face qualitative interviews (N=80; 20 per group) to elicit stories about engagement in HIV care. In addition to socio-demographic information, open-ended questions addressed (1) personal experiences with medical visits; (2) reasons for engagement and non-engagement in care for themselves and others like them; (3) non-medical services; and (4) strategies for improving HIV care engagement.

Interviews were conducted by masters- and doctoral-level interviewers and digitally recorded. Transcripts were checked by the interviewers and entered into NVivo (YMSM and TGW) or Dedoose (African immigrants and previously incarcerated) for systematic data management. Coding teams of 2-3 coders each from the E-M CFAR and from the HIV Center independently developed an initial set of codes from a subset of their own interviews. After applying the initial codes to several transcripts, the two teams worked together to develop a uniform codebook for all four populations.

We used both primary codes based on the interview questions and secondary codes that emerged from the data. For example, for the primary code “linkage to care,” secondary codes were “shopping for doctor,” “navigation of health care system,” and “initiation of ART.” For the primary code, “perceptions of care,” secondary codes were “continuity of care,” “frequency of care,” “medication adherence,” and “retention in care.” We also developed codes relevant to individual populations. Coded data were summarized in coding reports, and key themes were identified across the four groups.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The average age of African immigrants, who came from 9 countries, was 45 (range 27-61) years; 65% identified as female and 35% as male; all identified as Black. The average age of the previously incarcerated was 49 (range 25-60) years; 35% identified as female and 65% as male; 58% identified as Black (race), and 37% as Hispanic (ethnicity). The average age of TGW was 32 years (range 23-49); 75% identified as Black, and 40% as Hispanic. The average age of YMSM was 25 years (range 19-28); 65% identified as Black and 35% as Hispanic. Race and ethnicity were not mutually exclusive. Over three-quarters of the African immigrants were linked to care soon after their HIV diagnosis and, once linked, were consistently engaged. In contrast, only about half of previously incarcerated participants, YMSM, and TGW participants were consistently engaged in care.

Barriers and Facilitators to Engagement

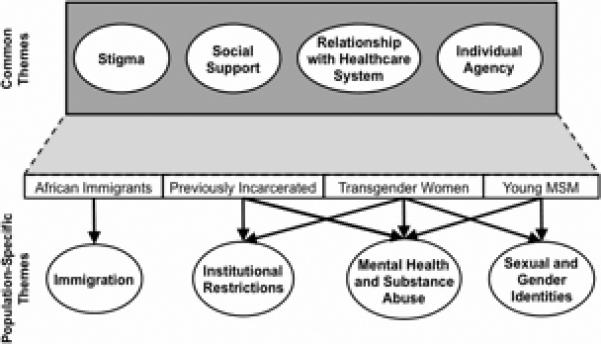

Thematic analysis identified barriers and facilitators to HIV care engagement that applied to all study populations as well as some that differed among groups (see Figure 1). The overarching domains of system-level, social-level, and individual-level factors framed participants’ discussions of HIV care engagement. In the quotations below, participants are identified by pseudonyms; as African immigrant (AI), previously incarcerated (PI), young MSM (YMSM), and transgender woman (TGW); with age and gender noted.

Figure 1.

Structural, Institutional, Social, and Individual-Level Enablers and Barriers to Engagement and Retention in HIV Care across Four Vulnerable Populations.

System-level factors

Specific features of social service, health care, and penal systems facilitate or obstruct consistent engagement in HIV care. Some system-level issues cut across populations, whereas others (e.g., healthcare in the penal system, immigration status, provider sensitivity to homosexuality or transgender concerns and practices) were specific to particular groups.

Housing

All four populations identified social services – housing, drug and alcohol treatment, food stamps, and transportation – as integral to their survival and quality of life and at least as important as their HIV care. HIV/AIDS Service Administration (HASA) housing support was repeatedly cited as a reason that people stayed in HIV care. TGW and YMSM who were homeless or struggling with housing when they were diagnosed with HIV said that obtaining secure housing through HASA allowed them to take better care of themselves.

“... having, you know, my own place and being able to live the way I want to live, I could focus on ... my health. I'm not worried about what I'm going to eat tomorrow, where I'm going to be tomorrow. So I feel more stable, and I feel like I'm in a place where I could, you know, worry about me....” (Vanessa, TGW, 25)

Having secure housing made them feel that someone cared for them and therefore helped them to stay in care.

“It is [easier to stay in care] because now you know you have a place to rest your head, a place to get away from the world. ... It shows that somebody loves you...”(Yvonne, TGW, 31)

Although secure housing was a gateway to other social services, which, in turn, facilitated HIV care engagement, dealing with these systems could be a source of stress.

“... this system is much better because I'm in my own space .... The thing with it is, though... you have to deal with the system. Parts of it are easier to deal with; parts of it are much more stressful. For instance, with this part of the system, you have to wait around a lot more..” (Bernadette, TGW, 25)

There was also a detrimental relationship between housing services policies and healthcare outcomes, in that only with a health decline could individuals to obtain housing.

“I was also homeless, waiting to get on HASA...because they kept saying, ‘You're not sick enough,’ because I was literally in a healthy T-cell range.... So I got really sick, got HASA.” (Yvonne, TGW, 31)

One participant, who had had undetectable viral load said,

“I couldn't get HASA because you had to have a certain viral load. ... And then ... I was going through a lot of stress ... and I stopped taking my medication. ... it messed up my viral loads... but that's the only way that I actually got the care that I needed.” (Warren, YMSM, 27)

Community-based social service organizations (CBOs)

CBOs played an important coordinating and facilitating role across populations. In addition to short-term housing upon release, CBOs were described by previously incarcerated PLWH as providing a critical lifeline for other needs. Obtaining medical, mental health, harm reduction/substance abuse, and social services through one coordinating CBO resulted in immediate attention to their most pressing concerns – often improving HIV care access and engagement.

“We had to do groups at [name of CBO]... They had a medical team there, but you could have went anyplace, but I figured I'm living here, why not take the medical because it's all together....” (Carolyn, PI, 59)

During incarceration, CBOs often enabled inmates to connect with services, including HIV care, in the community after release. This was especially important for those whose parole conditions prohibited them from returning to their old neighborhoods and, thus, re-engaging with previous providers. Since most had not received a list of HIV care providers upon release, they appreciated that CBOs referred them to non-stigmatizing high-quality HIV care.

“They have counselors come in and talk with you and they set you up for when you're coming out, tell you what to do and where to go.” (Sean, PI, 48)

HIV care navigation, (e.g., appointment reminders, health insurance monitoring) was a crucial service provided by CBOs. For instance, TGW and YMSM emphasized the importance of social service providers, adherence counselors, and other CBO staff in working with social service and healthcare systems and helping them remain engaged in HIV care.

“I see him [adherence counselor], like, once year, so it's not really often. But when I do see him, it's very helpful. Because, again, he just stresses the importance of adhering to it [treatment], yeah.” (Troy, YMSM, 28)

Finally, structured interpersonal support and learning through involvement in CBOs were identified as important coping strategies for participants themselves or other PLWH.

“Another big thing that's made me stay in care is ... [being] part of my youth program ... that's actually kept me more informed about things ....” (Joe, YMSM, 25)

“When they have ... a community-based place where they can go and either talk what's on their mind, some place where they can go and be social and learn at the same time too.... When they're feeling better, they're going to want to keep going.” (Sean, PI, 48)

Immigration status

In contrast, African immigrants spoke less often about using CBOs and social service programs to support HIV care engagement. Because many were undocumented and most had emigrated from countries with suboptimal HIV care, fear of deportation made them unwilling to risk seeking social services. Further, most did not know they could be treated for HIV in the US regardless of their immigrant status; many were diagnosed late in their illness, when they were pregnant or acutely ill.

Healthcare providers

Relationships with HIV care providers had a significant impact on engagement in care for all four populations. In general, good communication, caring attitudes, and trust were essential to consistent engagement in HIV care, whereas not feeling respected, cared about, or listened to were reasons to disengage.

Most African immigrants trusted their doctors, were eager to please them and, once linked to care, reported high engagement and adherence. They were grateful for how caring their doctors were, with many saying that the doctor “treated them like family” and did not stigmatize them because of their HIV status.

“...my doctor...he takes care of me. He also give me his cell phone number just in case.” (Molly, AI, 38)

YMSM also cited the importance of providers who were invested in their health and well-being and talked about patient-provider relationships as friendships or even family.

“...Like, if I have questions... she just really cares... It's like a mom... We talk about everything. We talk about my relationships...I can check in with her.” (Darrell, YMSM, 27)

“He's very blunt. Straightforward. He likes to tell it how it is; he doesn't hold anything back. He gives you the best advice that I've probably ever had from any doctor, and he just makes you feel really comfortable. He treats you kind of like a friend, mostly. And he's homosexual, so that it made it easier, too.” (Joe, YMSM, 25)

Similar to the other groups, YMSM stressed the importance of provider-patient communication, wanting providers to explain treatment options thoroughly and address their concerns.

“He's very thorough... he explains everything to a T. He's very articulate, and he's very knowledgeable. And any and all questions that ... I have for him, he always answers it with ease and attitude-free.” (Troy, YMSM, 28)

“I believe a lot of people who are HIV-positive, even those who are in denial about it, would go to places like that; you know, who had doctors... like the one I have, being honest with you about your health, not holding any punches but reassuring you that it's not the end. Yeah, I think if there were more places like [name of CBO] ... [HIV+ people] would probably be sticking with the HIV treatment.” (Bobbie, YMSM, 28)

However, YMSM also preferred to be active participants in their own healthcare. Providers who were not receptive to answering questions or failed to address doubts and concerns or collaborate with patients impeded effective communication, imperiling patient engagement.

“....a doctor would have authority over, you know, what course of treatment might be best for my body. But that doesn't change the fact that we're two people exchanging information...I don't want to act like I'm talking to my seventh grade assistant principal.” (Pablo, YMSM, 22)

Both TGW and YMSM wanted providers to make them feel comfortable in sharing their sexual and gender identity and practices and to be knowledgeable about homosexuality and transgender issues. For TGW, this included the provider understanding gender identity, hormone therapy and drug interactions, and the complexities of treating gender-transitioning HIV-positive patients. Both YMSM and TGW declared that providers’ lack of training about and affirmation of gender and sexual identities would hinder HIV care engagement to the extent that they might drop out of care.

In jails and prisons, lack of trust in medical providers and poor medical care were powerful deterrents to HIV care engagement. Formerly incarcerated participants reported that doctors in prisons did not explain what a positive HIV test meant and what treatments were available, and they were skeptical about doctors’ commitment to prisoner health and ability to deliver adequate care.

“Don't trust doctors in prison. They are not well-qualified, do not care about the patient...I just didn't trust his judgment because we were a bunch of criminals and they treat us like shit.” (Mark, PI, 25)

Participants also cited lack of access to a steady supply of ART while incarcerated. Many reported that, when arrested, their antiretroviral medication was at home or was confiscated, resulting in treatment interruptions until the medications were returned or the penal system health provider prescribed ART (frequently as generic or other substitute medications).

Social factors: stigma and social support

Stigma

Stigma was a powerful deterrents to entering and staying in HIV care across populations. For example,

“There's a lot of stigma surrounding HIV .... They [others who get diagnosed] may have heard of someone passing away from it, or they may have even ... heard horror stories from way back when. And they kind of carry that stigma with them, so when they find out that they're HIV-positive, then, you know, they don't want to deal with it.” (Terrance, YMSM, 22)

“Maybe they think about stigmatization; maybe they think... people gonna know ... who they are and that's why they don't want to go [for care]. Even [CBO name]– some people don't want to go there because they think people gonna know you are HIV.”(Walter, AI 51)

Incarcerated PLWH often were seen for care by a particular doctor or clinic, allowing other inmates to deduce that they were HIV-positive. Thus, many of the previously incarcerated had not shared their diagnosis with the penal health care system, preferring to forego treatment while incarcerated rather than face HIV stigma and rejection by other inmates and officers – particularly since surviving prison or jail unscathed can depend on the protection of others.

“The concept in jail is that if you are HIV positive, everyone will take that against you. That they don't want to be your friend .... They don't want to shake your hand, they don't want to share...That is one of the reasons why I didn't want to take medication. I tried not to go to the hospital much...“ (Nomar, PI, 54)

Most African immigrants hid their diagnosis from their families and communities on whom they were dependent for housing, jobs, child-care, and social support. Several reported that when their HIV status was accidently disclosed, they were fired from their jobs, ostracized, or evicted. Thus, membership in their local immigrant community was a double-edged sword – both an indispensable resource for support and a source of extreme vulnerability if that support were withdrawn.

“...I just want to keep things only in my close family. ... one of my other family members don't know anything yet. They ... have their misjudgments and stigma about people that have it. They tend to treat people differently.” (John, AI, 36)

Further, if going to an HIV doctor or filling prescriptions might reveal their status, many would sacrifice care to preserve the secret.

“I wanted to be very discreet because I didn't want a hospital or clinic close to home ..., maybe run into people in the neighborhood that I didn't want to really know about my status ... I didn't want them somewhere where they see me there ... and say, “Oh, you're on this floor ... We know what floor you're going for and who's on that floor.” (John, AI, 36)

Although all four groups talked about how HIV stigma kept them from engaging in care, types of stigma specific to each population also emerged, focused on e.g., sexual identity for YMSM, gender identity for TGW, incarceration or substance abuse for recently released prisoners, and undocumented status for the African immigrants. For some, disclosure of HIV status would add another layer of stigmatization. For instance, TGW participants reported that the compounded stigma of being transgender and HIV-positive led them to avoid getting care.

“... being transgender with HIV is harder than just being a straight person, or a normal gay person. Because you have to go through a lot, to find out who you really are. You can never be who you want to be... you going through all this psychological shit. And when you get through the end of the day, you don't give a damn.” about medical care no more. You just don't care.” (Jennifer, TGW, 23)

Recently released prisoners reported feeling stigmatized because of their substance use or incarceration history. This interfered with reconnecting to family members for social support and to the health care system, where they believed they would be treated disrespectfully. Whether actually encountered or anticipated, this stigma was detrimental to engagement in HIV care, often leading to the decision not to access care at a particular clinic/hospital.

“I knew from ... hearing other girls who were HIV-positive how they got treated. I didn't want to be treated that way. ... I was afraid of going to a hospital and I was afraid of and didn't know how to go about finding another specialist. I didn't even know that there were doctors that really specialized in that... so I went almost a year without any type of medication once the ones that he gave me ran out, and any type of doctor's care.” (Lydia, PI, 44)

Social support

Yet the negative consequences of stigma were buffered by support from friends, family, and peers, and most participants identified this social support – especially from people living in similar circumstances – as a facilitator of HIV care engagement, giving meaning to life, and being helpful in making connections and in initiating and staying in HIV care.

“Because I met a friend of mine in parole when I went to parole and he's positive....I told him, “I know I'm positive, but I don't want to accept that.” Me and him became partners, intimate, and he helped me accept that and to let go of that denial. He took me to my first doctor, which I'm still with.” (Joan, PI, 53)

“At first [my sister]...was a little bit shocked and kind of disappointed, I guess, but once she found out the situation and how it came about, she was more understanding and just, you know, she became kind of like my mother. She's always getting on me about take my medicine, and make sure I go to the doctor, and make sure I do this and make sure I do that. So, she's been a big help.” (Joe, YMSM, 25)

“Yes, because when I find out ... I don't want to go to the hospital ... I want to be dead. And, after that day, my cousin's friend who used to work here, they call me, and they give me the appointment to come in to see the doctor. And when I go there, ... they put me on the medicine.” (Molly, AI, 38)

However, some TGW reported significant lack of social support from family or friends, and expected little support if they disclosed their HIV status, highlighting the isolating effects of being both transgender and HIV-positive:

“I haven't opened up to family .they're already in a life crisis about me being transgendered. The last thing I need them to do is start drinking vodka all night because of my status. Start talking about, oh, what we did wrong, you know.” (Vanessa, TGW, 25)

In addition to obtaining social support from their communities, many African immigrants were parents or grandparents, which was a powerful motivator to stay healthy, see the doctor, and take medications regularly.

“Yeah, I listen to the doctor. I have to be there for my kids.” (Naya, AI, 40)

“I believe some people don't even go for treatment; they stop. In my own opinion – for me only – I would like to live for my kids... Even if I don't know when I'm going to die, I want to be there for my kids when they grow up. Even if I leave this world, I would like to leave them when they're much older. Yes, so it's important for me to take my medication; it's important for me to see the doctor...” (Norma, AI, 36)

In addition to receiving social support, providing support facilitated one's own healthcare management. For instance, previously incarcerated participants who were peer educators appreciated the opportunity to “give back” by educating other PLWH and felt less stigmatized and better able to prioritize their own health care.

“I was taking them [HIV medications] as prescribed this time because I was part of the ACE program, and I wanted to become a peer educator there. So in order for me to become a peer educator, I had to be in adherence with everything. In order to teach somebody I had to teach myself first.” (Carolyn, PI, 59)

Similarly, some YMSM and TGW reported that volunteering or working in HIV-related services helped them stay in care; they were able to build a sense of community, cultivate a support system, and become positive role models for their peers.

“Another big thing that's made me stay in care is another program that I'm actually in... they create PSAs [public service announcements] geared towards people living with HIV... the importance of medications and so forth. ... so that's actually kept me more informed..” (Joe, YMSM, 25)

For some, becoming a peer educator for their community enabled them to educate themselves and take care of their own health as well.

“I facilitate groups here... I try to utilize all the tools that I provide to others, applying it to me...” (Jessica, TGW, 46)

Individual-level factors

Often, other life stressors took precedence over HIV healthcare needs. For instance, recently released prisoners often lacked housing, and the rifts created by their substance use and mental health problems resulted in few family members being willing to house them. Substance abuse issues often overrode other health care demands, including engagement in HIV care and medication adherence. Although some hoped to change their luck, stay clean, get a job, and avoid future incarceration, others spoke of the temptations posed by the street lifestyle once released.

“[Being in prison] is the time to rest, work out, eat well – it's like recuperation time when you are getting ready to leave...and then you get out and start getting high, smoking crack cocaine.” (Warren, PI,54)

“... you know deep down in your mind you're supposed to... but you get the fuck-its. You get a lot of that.” (Bonnie, PI, 55)

Similarly, many African immigrants described multiple stressors including poverty and hunger, rape, domestic violence, death and loss, and depression.

“... I'm kind of scared of people because of what happened to me. It's not only HIV status, but I've been through domestic violence, too, with my kids’ dad.” (Louise, AI, 27)

Urgent daily problems requiring their immediate attention included feeding young children, finding transportation to work, and housing; attending to these often impeded optimal HIV care engagement.

However, stories from all four populations spoke to their resilience and how their personal strength and accountability facilitated engagement in HIV care. All groups described HIV care engagement as primarily a personal decision influenced by their motivation to maintain health, personal strength, accountability, and self-reliance.

“If I want to live, I got to stay in [care]. ... If I don't stay, I'm going to die. .... If I could find something new to help me, I would try it. I would try it. Yeah, I would try it.” (Karen, TGW, 48)

“[Staying in care] kind of comes natural, I guess. I don't know if anything really makes it easy. I just do what I have to do, you know, because I know what's expected of me if I want to stay alive and stay healthy.” (Troy, YMSM, 28)

For some TGW, remaining engaged in HIV care was linked to their affirmation as women and desire to live happily and healthfully.

“I'm a woman now. I look how a woman acts.... And living with HIV as a transgender – how will I put that now? It's like, you want to still look pretty.... You don't want to break out into no pneumonia. You don't want to die early. You don't want to be into that obstacle that -- now that it's like a wake-up call.” (Nicole, TGW, 25)

Members of all four groups expressed appreciation for the healthcare resources available to them. In particular, most African immigrants were acutely aware of the differences in the availability of HIV treatment and care in the US compared to their home countries.

“I know I have HIV and I need the doctor...to be alive...and they give me all this for free.... I have to thank America for that [crying].” (Lonnie, AI, 60)

Finally, many participants described staying engaged in HIV care as a survival mechanism and took strength from knowing that they could prolong their lives not only for themselves, but for their families and communities.

“I think just seeing like, some of my peers, you know, give up on themselves, and actually just watching them pass away. And I didn't want to be just a number as just a person to pass away. I wanted to be a number as, ‘I'm in this fight, and I'm going to keep trying to progress for me. Not just for myself, but for my family, and also for my community.’ So, if a person sees that I'm, you know, hanging in the race, I can be persuasive to help someone else ... Either you're, you know, taking care of yourself, or letting yourself go to waste. And I refuse to do the second one” (Darrell, YMSM, 27)

DISCUSSION

Engaging particularly vulnerable populations of PLWH in consistent HIV care is critical both for optimizing their own health and for preventing further transmission of HIV by those with unsuppressed viral loads. New York City, with the largest number of infected people of any US city, struggles to meet the proposed national and local targets of engagement in HIV care and suppressed viral load.10

Stigma and discrimination, lack of health insurance, unemployment, social and economic marginalization, mental illness, substance use, unstable housing, and mistrust of the medical system were documented as barriers to HIV care engagement in our study as well in studies by others.7, 19-21

Our data identified some issues common across populations and some specific to particular populations. Even for issues common to all four groups, our in-depth qualitative interviews revealed nuanced differences that can guide best practice and public health policy for each population and highlighted the need to tailor interventions. Our findings were also notable for the many examples participants offered of strategies to promote engagement – such as services coordination and provider sensitivity training – that could be adopted or more widely implemented to fill gaps in support for HIV care.

All four populations emphasized the essential role of community-based social service agencies. Notably, these CBOs worked differently with each group, tailoring their services to the population's needs and emphasizing different service delivery points to optimizing HIV care engagement. Some penal systems, for example, involved CBOs before prisoners’ release to optimize continuity of HIV care in the community. This was particularly important if the conditions of parole prohibited a previously incarcerated individual from returning to his or her former community and, perhaps, former care facilities. For all populations, CBOs provided supportive and accepting case management and peer navigation that were critical in engaging PLWH – particularly those who were stigmatized – in HIV care. Case management, an evidence-based strategy for increasing retention in HIV primary care among young HIV-positive Latino and African-American MSM,22 also appears to have significant benefits for previously incarcerated individuals and African immigrants.

We cannot overemphasize the importance of housing to HIV care engagement and viral load suppression. People without an address are at a profound disadvantage in gaining access to services; people without a home cannot create the structure and stability they need to access care and adhere to medications. People who are living with others and dependent on their good will may be vulnerable to abuse and mistreatment and may keep their HIV status secret to ensure a continued domicile. Public health policy should continue to support the role of CBOs as partners with the health care system in supporting engagement in HIV care,, particularly among the hardest-hit and most disenfranchised communities, and interested citizens might advocate for increased funding for such programs. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and NY State have begun to recognize this need: the ACA supports the ‘health homes’ model for chronic conditions, and NYC Medicaid reform through health homes has begun to reimburse for many CBO counseling services not covered formerly.

A second system-level intervention strategy would target the provider-patient relationship. All four groups cited the importance of providers with whom they felt comfortable and secure, whether because of the provider's accessibility and supportive, non-stigmatizing behavior; the respect and collaboration shown to the patient (e.g., engaging in shared decision-making while communicating about medical issues clearly); or the provider's knowledge about and sensitivity to patient concerns (e.g., sexual orientation and gender identity, HIV care in the context of hormone treatment for TGW). Best practices for HIV care providers could include training and capacity-building in these domains, in medical and nursing schools, in residency training, and in licensing examinations. This will be particularly important if national initiatives to move HIV care to primary care management are successful.

For all four groups, stigma led people to remain hidden and potentially disengaged from care. Again, community social service organizations played a key role in diminishing the effects of stigma through structured social support and referral to non-stigmatizing supportive health care facilities. HIV healthcare facilities themselves can institutionalize best practices that strongly discourage stigmatization and promote acceptance and supportive attitudes among all staff and providers.

Study Limitations

As with all qualitative research, findings are best used to generate insights, themes, and new hypotheses, and qualitative interviews do not necessarily reflect the frequency of the engagement barriers and facilitators we identified. In addition, our recruitment strategies led us to identify participants who were more likely to be engaged in HIV care. Although most whom we interviewed had a checkered history of care engagement and their stories were very instructive, we would have benefited from talking with more PLWH who were not currently engaged in care.

Conclusions

Some barriers to HIV care engagement affected people's motivation to engage; others affected their ability to engage. At the time of the interview, most participants were strongly motivated to engage in care but experienced hurdles and challenges that made it hard. Daily life stresses often put HIV care secondary to finding a place to live and/or something to eat, feeding a drug addiction, or finding a job. The discrimination and internalized stigma that could result from disclosure of HIV were heavy burdens that most participants explicitly cited as barriers to care engagement.

Many participants described times of lost motivation to engage in HIV care; this was often rooted in pervasive demoralization, a sense of diminished worth, or simple weariness. But, narratives also revealed what helped participants regain their willingness to seek care, including the intercession of family members, friends and peers, peer navigators and community health workers; physicians who “went beyond” to reach out through personalized calls/messages, make home visits, and cajole patients back; strength of will and personal agency; and traumatic events, including health problems, that resurrected their fear of death and disability and motivated change.

As we seek strategies to reduce HIV transmission through undetectable viral loads, we must provide an individualized platform of services through which PLWH can achieve this goal, both for their own health outcomes and for prevention of infection of others. Particularly vulnerable populations, such as the four on which we focused, need system-, social-, and individual-level support to maintain both high motivation to participate in care and high persistence in overcoming obstacles to care over the long term. CBOs, health care systems, penal systems, governments, and communities must commit resources to overcome the life-long challenges to engagement faced by these groups.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants number P30-MH43520 and P30-AI087714

Footnotes

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of NIH. Responsibility for the content of this report rests solely with the authors.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castilla J, Del Romero J, Hernando V, Marincovich B, Garcia S, Rodriguez C. Effectiveness of HAART in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(1):96–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000157389.78374.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Gay C, Kashuba AD, Blower S, Paxton L. Narrative review: antiretroviral therapy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:591–601. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr., et al. Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das M, Chu PL, Santos G-M, Scheer S, Vittinghoff E, McFarland W, Colfax GN. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011068.t001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson M, Laraque F, Mavronicolas H, Braunstein S, Torian L. Linkage and retention in care and the time to HIV viral suppression and viral rebound – New York City. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.959463. Published online 22 Sep 2014. DOI: 10.1080/09540121.2014.959463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:41–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The White House Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP) [18 September 2014];National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. 2010 Available at www.whitehouse.gov/onap.

- 9.Gov. [18 September 2014];Cuomo releases 3-point plan to end AIDS epidemic in New York. 2014 Jun 29; Available at https://www.governor.ny.gov/press/06292014-end-aids-epidemic.

- 10.Dietz PM, Krueger AL, Wolitski RJ, et al. [19 October 2014];State HIV Prevention Progress Report. 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/progressreports/index.html. Published August 2014.

- 11.Blanas DA, Nichols K, Bekele M, Lugg A, Kerani RP, Horowitz CR. HIV/AIDS among African-Born residents in the United States. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2013;15:718–724. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9691-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page LC, Goldbaum G, Kent JB, Buskin SE. Access to regular HIV care and disease progression among black African immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1230–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien H- S, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Reports. January-February. 2005;120:84–88. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: Reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. June 15. 2004;38:1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montague BT, Rosen DL, Solomon L, Nunn A, Green T, Costa M, Baillargeon J, Wohl DA, Paar DP, Rich JD, on behalf of the LINCS Study Group Tracking linkage to HIV care for former prisoners. A public health priority. Virulence. 2012 May-Jun;33:319–324. doi: 10.4161/viru.20432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnus M, Jones K, Phillips G, 2nd, Binson D, Hightow-Weidman LB, Richards-Clarke C, Wohl AR, Outlaw A, Giordano TP, Quamina A, Cobbs W, Fields SD, Tinsley M, Cajina A, Hidalgo J, YMSM of color Special Projects of National Significance Initiative Study Group Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: results from the outreach, care, and prevention to engage HIV-seropositive young MSM of color special project of national significance initiative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr 1;53(4):529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b56404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, Johnson MO. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann. Behav. Med. Feb. 2014;47(1):5–16. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jovchelovitch S, Bauer MW. Narrative interviewing. In: Bauer, Martin W, Gaskell G, editors. Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook. SAGE; London, UK: 2000. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anthony MN, Gardner L, Marks G, Anderson-Mahoney P, Metsch LR, Valverde EE, del Rio C, Loughlin AM, for the antiretroviral treatment and access study (ARTAS) study group Factors associated with use of HIV primary care among persons recently diagnosed with HIV: Examination of variables from the behavioural model of health-care utilization. AIDS Care. February. 2007;19(2):195–202. doi: 10.1080/09540120600966182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christopoulos KA, Das M, Colfax GN. Linkage and retention in HIV care among men who have sex with men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S214–S222. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garland PM, Valverde EE, Fagan J, Beer L, Sanders C, Hillman D, Brady K, Courogen M, Bertolli J, for the NIC Study Group HIV counseling testing and referral experiences of persons diagnosed with HIV who have never entered HIV care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(3 Suppl):117–127. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wohl AR, Garland WH, Wu J, Au CW, Boger A, Dierst-Davies R, Carter J, Carpio F, Jordan W. A youth-focused case management intervention to engage and retain young gay men of color in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2011;23(8):988–997. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]