Abstract

Objectives

Recurrent caries at the margins is a primary reason for restoration failure. The objectives of this study were to develop bonding agent with the double benefits of antibacterial and remineralizing capabilities, to investigate the effects of NACP filler level and solution pH on Ca and P ion release from adhesive, and to examine the antibacterial and dentin bond properties.

Methods

Nanoparticles of amorphous calcium phosphate (NACP) and a quaternary ammonium monomer (dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate, DMADDM) were synthesized. Scotchbond Multi-Purpose (SBMP) primer and adhesive served as control. DMADDM was incorporated into primer and adhesive at 5% by mass. NACP was incorporated into adhesive at filler mass fractions of 10%, 20%, 30% and 40%. A dental plaque microcosm biofilm model was used to test the antibacterial bonding agents. Calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) ion releases from the cured adhesive samples were measured vs. filler level and solution pH of 7, 5.5 and 4.

Results

Adding 5% DMADDM and 10–40% NACP into bonding agent, and water-aging for 28 days, did not affect dentin bond strength, compared to SBMP control at 1 day (p > 0.1). Adding DMADDM into bonding agent substantially decreased the biofilm metabolic activity and lactic acid production. Total microorganisms, total streptococci, and mutans streptococci were greatly reduced for bonding agents containing DMADDM. Increasing NACP filler level from 10% to 40% in adhesive increased the Ca and P ion release by an order of magnitude. Decreasing solution pH from 7 to 4 increased the ion release from adhesive by 6–10 folds.

Significance

Bonding agents containing antibacterial DMADDM and remineralizer NACP were formulated to have Ca and P ion release, which increased with NACP filler level from 10% to 40% in adhesive. NACP adhesive was “smart” and dramatically increased the ion release at cariogenic pH 4, when these ions would be most-needed to inhibit caries. Therefore, bonding agent containing DMADDM and NACP may be promising to inhibit biofilms and remineralize tooth lesions thereby increasing the restoration longevity.

Keywords: antibacterial bonding agent, nanoparticles of amorphous calcium phosphate, ion release, dental plaque microcosm biofilm, dentin bond strength, caries

1. Introduction

Resin composites are the principal material for tooth cavity restorations due to their esthetics and direct-filling capability [1–4]. Advances in polymers and fillers have significantly enhanced the composite properties and clinical performance [5–11]. However, a serious drawback is that composites tend to accumulate more biofilms/plaques in vivo than tooth enamel and other restorative materials [12,13]. Biofilms with exposure to fermentable carbohydrates produce acids and are responsible for tooth caries [14,15]. Furthermore, composite restorations are bonded to the tooth structure via adhesives [16–19]. The bonded interface is considered the weak link between the restoration and the tooth structure [16]. Hence extensive studies were performed to increase the bond strength and determine the mechanisms of tooth-restoration adhesion [20–24]. One approach was to develop antibacterial adhesives to reduce biofilms and caries at the margins [25–28]. The rationale was that, after tooth cavity preparation, there are residual bacteria in the dentinal tubules. In addition, marginal leakage during service could also allow new bacteria to invade into the tooth-restoration interfaces. Therefore, antibacterial bonding agents would be highly beneficial to combat bacteria and caries [29,30].

Accordingly, efforts were made to synthesize quaternary ammonium methacrylates (QAMs) and develop antibacterial resins [25,31–35]. The 12-methacryloyloxydodecyl-pyridinium bromide (MDPB)-containing adhesive effectively inhibited oral bacteria growth [26,29]. Antibacterial adhesive containing methacryloxyl ethyl cetyl dimethyl ammonium chloride (DMAE-CB) was also synthesized [27]. Other studies developed a quaternary ammonium dimethacrylate (QADM) for incorporation into resins [33,36,37]. Recently, a new quaternary ammonium monomer, dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate (DMADDM), was synthesized and imparted a potent anti-biofilm activity to bonding agent [38].

Another approach to combat caries was to incorporate calcium phosphate (CaP) particles to achieve remineralization capability [39–42]. Composites were filled with amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) in which the ACP particles had diameters of several µm to 55 µm [43]. ACP composites released supersaturating levels of calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) ions and remineralized enamel lesions in vitro [43]. One drawback of traditional CaP composites is that they are mechanically weak and cannot be used as bulk restoratives [39,40]. More recently, nanoparticles of ACP (NACP) were synthesized and incorporated into resins [44,45]. NACP nanocomposite released high levels of Ca and P ions while possessing mechanical properties similar to commercial composite control [44]. NACP nanocomposite neutralized acid challenges [45], remineralized enamel lesions in vitro [46], and inhibited caries in vivo [47]. Due to the small particle size and high surface area, NACP in resin would have three main advantages: (1) improved mechanical properties [44], (2) high levels of ion release [44], and (3) being able to flow with bonding agent into small dentinal tubules [48]. However, the Ca and P ion release from bonding agent with various amounts of NACP has not been measured in previous studies.

The objectives of this study were to develop bonding agent with double benefits of antibacterial and remineralizing capabilities, to investigate the effect of NACP filler level and solution pH on Ca and P ion release from the adhesive, and to examine the antibacterial and dentin bonding properties. It was hypothesized that: (1) Incorporation of DMADDM and NACP and water-aging for 1 month will not negatively affect the dentin bond strength; (2) DMADDM will impart a strong antibacterial activity to bonding agent, while NACP will have no effect on antibacterial activity; (3) Ca and P ion release will be directly proportional to NACP filler level in adhesive: (4) NACP adhesive will be “smart” to increase the ion release at acidic cariogenic pH, when these ions would be most-needed to inhibit caries.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of NACP and DMADDM

Nanoparticles of ACP (Ca3[PO4]2), referred to as NACP, were synthesized using a spray-drying technique as described previously [44,45]. Briefly, calcium carbonate (CaCO3, Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ) and dicalcium phosphate anhydrous (CaHPO4, Baker Chemical, Phillipsburg, NJ) were dissolved into an acetic acid solution to obtain final Ca and P ionic concentrations of 8 mmol/L and 5.333 mmol/L, respectively. The Ca/P molar ratio for the solution was 1.5, the same as that for ACP. The solution was sprayed into the heated chamber of the spray-drying apparatus. The dried particles were collected via an electrostatic precipitator (AirQuality, Minneapolis, MN), yielding NACP with a mean particle size of 116 nm [44].

The synthesis of DMADDM with an alkyl chain length of 12 was described elsewhere [38]. Briefly, a modified Menschutkin reaction method was used in which a tertiary amine group was reacted with an organo-halide [33,36–38]. 2-bromoethyl methacrylate (BEMA) (Monomer-Polymer and Dajac Labs, Trevose, PA) was used as the organo halide, and 1-(dimethylamino)docecane (DMAD) (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) was the tertiary amine. Ten mmol of DMAD and 10 mmol of BEMA were added in a 20 mL scintillation vial with a magnetic stir bar [38]. The vial was capped and stirred at 70 °C for 24 h. After the reaction was completed, the ethanol solvent was removed via evaporation, yielding DMADDM as a clear, colorless, and viscous liquid. The reaction and the products were verified via Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in a previous study [38].

2.2. Incorporation of DMADDM and NACP into bonding agent

Scotchbond Multi-Purpose (SBMP, 3M, St. Paul, MN) was used as the parent bonding system to test the effects of incorporation of DMADDM and NACP. According to the manufacturer, SBMP etchant contained 37% phosphoric acid. SBMP primer single-bottle contained 35–45% 2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA), 10–20% copolymer of acrylic and itaconic acids, and 40–50% water. SBMP adhesive contained 60–70% BisGMA and 30–40% HEMA.

DMADDM was mixed with SBMP primer at DMADDM/(SBMP primer + DMADDM) = 5% by mass, following previous studies [30,49]. Similarly, 5% of DMADDM was mixed with SBMP adhesive. NACP was mixed into the adhesive at mass fractions of: 10%, 20%, 30% and 40%. NACP filler levels higher than 40% were not used because the dentin bond strength decreased in preliminary study. The following six bonding systems were tested:

Unmodified SBMP primer P and adhesive A (designated as “SBMP control”);

P + 5% DMADDM, A + 5% DMADDM (designated as “P&A + 5DMADDM”);

P + 5% DMADDM, A + 5% DMADDM + 10% NACP (P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 10NACP);

P + 5% DMADDM, A + 5% DMADDM + 20% NACP (P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 20NACP);

P + 5% DMADDM, A + 5% DMADDM + 30% NACP (P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 30NACP);

P + 5% DMADDM, A + 5% DMADDM + 40% NACP (P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 40NACP).

2.3. Dentin shear bond strength testing

Caries-free human third molars were cleaned and stored in 0.01% thymol solution. Flat mid-coronal dentin surfaces were prepared by cutting off the tips of crowns with a diamond saw (Isomet, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) [38,49]. Each tooth was embedded in a poly-carbonate holder (Bosworth, Skokie, IL) and ground perpendicular to the longitudinal axis on 320-grit silicon carbide paper until the occlusal enamel was removed. The dentin surface was etched with 37% phosphoric acid gel for 15 s and rinsed with water for 15 s [38,49]. A primer was applied with a brush-tipped applicator and rubbed in for 15 s. The solvent was removed with a stream of air for 5 s, then an adhesive was applied and light-cured for 10 s (Optilux). A stainless-steel iris, having a central opening with a diameter of 4 mm and a thickness of 1.5 mm, was held against the adhesive-treated dentin surface. The opening was filled with a composite (TPH) and light-cured for 60 s. The bonded specimens were stored in water at 37 °C for 1 day or 28 days. A chisel with a Universal Testing Machine (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN) was aligned to be parallel to the composite-dentin interface [38,49]. The load was applied at a rate of 0.5 mm/min until the bond failed. Dentin shear bond strength, SD, was calculated as: SD = 4P/(πd2), where P is the load at failure, and d is the diameter of the composite [38,49].

2.4. Saliva collection for dental plaque microcosm biofilm model

The dental plaque microcosm biofilm model was approved by the University of Maryland. This model has the advantage of maintaining much of the complexity and heterogeneity of in vivo plaques [50]. To represent the diverse bacterial populations, saliva from ten healthy individuals was combined for the experiments. Saliva was collected from healthy adult donors having natural dentition without active caries or periopathology, and without the use of antibiotics within the past three months [38,49]. The donors did not brush teeth for 24 h and stopped any food/drink intake for at least 2 h prior to donating saliva. Stimulated saliva was collected during parafilm chewing and kept on ice. An equal volume of saliva from each of the ten donors was combined, and diluted to 70% saliva and 30% glycerol. Aliquots of 1 mL were stored at −80 °C for subsequent use [38,49].

2.5. Resin specimens for biofilm experiments

Primer/adhesive/composite tri-layer disks were fabricated following previous studies [38,49]. First, each primer was brushed on a glass slide, then a polyethylene mold (inner diameter = 9 mm, thickness = 2 mm) was placed on the glass slide. After drying with a stream of air, 10 µL of an adhesive was applied and cured for 20 s with Optilux [38,49]. Then, the composite (TPH) was placed on the adhesive to fill the mold and cured for 1 min (Triad 2000, Dentsply, Milford, DE). The cured disks were agitated in water for 1 h to remove any uncured monomers, following a previous study [51]. The disks were then immersed in distilled water at 37 °C for 1 d. The disks were then sterilized with an ethylene oxide sterilizer (Anprolene AN 74i, Andersen, Haw River, NC) and de-gassed for 7 days, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The specimens were then used for biofilm experiments.

2.6. Bacteria inoculum and live/dead biofilm staining

The saliva-glycerol stock was added, with 1:50 final dilution, to a growth medium as inoculum. The growth medium contained mucin (type II, porcine, gastric) at a concentration of 2.5 g/L; bacteriological peptone, 2.0 g/L; tryptone, 2.0 g/L; yeast extract, 1.0 g/L; NaCl, 0.35 g/L, KCl, 0.2 g/L; CaCl2, 0.2 g/L; cysteine hydrochloride, 0.1 g/L; haemin, 0.001 g/L; vitamin K1, 0.0002 g/L, at pH 7 [52]. Each tri-layer disk was placed into a well of a 24-well plate with the primer side facing up. Each well was filled with 1.5 mL of inoculum, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After 8 h, each specimen was transferred into a new 24-well plate with 1.5 mL fresh medium, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 16 h. Then, each specimen was transferred into a new 24-well plate with 1.5 mL fresh medium, and incubated for 1 day. This totaled 2 days of incubation, which was shown to form biofilms on resins [38,49].

Disks with 2-day biofilms were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and live/dead stained using the BacLight live/dead bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Imaging was performed via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM 510, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Three randomly-chosen fields of view were photographed for each of six disks, yielding a total of 18 images for each bonding agent.

2.7. MTT assay of biofilm metabolic activity

A MTT assay (3-[4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used to examine the metabolic activity of biofilms [53]. MTT is a colorimetric assay that measures the enzymatic reduction of MTT, a yellow tetrazole, to formazan. Disks with 2-day biofilms (n = 6) were transferred to a new 24-well plate, and 1 mL of MTT dye (0.5 mg/mL MTT in PBS) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 1 h. During the incubation, metabolically active bacteria metabolized the MTT, a yellow tetrazole, and reduced it to purple formazan inside the living cells. Disks were then transferred to new 24-well plates, and 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to solubilize the formazan crystals. The plates were incubated for 20 min with gentle mixing at room temperature. Two hundred µL of the DMSO solution was collected, and its absorbance at 540 nm was measured via a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A higher absorbance means a higher formazan concentration, which indicates more metabolic activity in the biofilms [38,49,53].

2.8. Lactic acid production by biofilms adherent on resin disks

Disks with 2-day biofilms (n = 6) were rinsed with cysteine peptone water (CPW) to remove loose bacteria, and then transferred to 24-well plates containing 1.5 mL buffered-peptone water (BPW) plus 0.2% sucrose [38,49]. The specimens were incubated for 3 h to allow the biofilms to produce acid. The BPW solutions were collected for lactate analysis using an enzymatic method. The 340-nm absorbance of BPW was measured with the microplate reader. Standard curves were prepared using a standard lactic acid (Supelco Analytical, Bellefonte, PA) [38,49].

2.9. Colony-forming unit (CFU) counts of biofilms adherent on resin disks

Disks with 2-day biofilms were transferred into tubes with 2 mL CPW, and the biofilms were harvested by sonication and vortexing via a vortex mixer (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) [38,49]. Three types of agar plates were prepared. First, tryptic soy blood agar culture plates were used to determine total microorganisms [38,49]. Second, mitis salivarius agar (MSA) culture plates, containing 15% sucrose, were used to determine total streptococci [38,49,54]. This is because MSA contains selective agents crystal violet, potassium tellurite and trypan blue, which inhibit most gram-negative bacilli and most gram-positive bacteria except streptococci, thus enabling streptococci to grow [54]. Third, cariogenic mutans streptococci are known to be resistant to bacitracin, and this property is often used to isolate mutans streptococci from the highly heterogeneous oral microflora. Hence, MSA agar culture plates plus 0.2 units of bacitracin per mL was used to determine mutans streptococci [38,49,55]. The bacterial suspensions were serially diluted and spread onto agar plates for CFU analysis [38,49].

2.10. Calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) ion release measurement

Preliminary studies indicated that when NACP was incorporated into SBMP adhesive, there was no loss in dentin bond strength. However, when NACP was incorporated into SBMP primer, the dentin bond strength decreased. Hence NACP was incorporated into SBMP adhesive but not into primer. Four groups of materials were tested for Ca and P ion release: (i) SBMP adhesive + 5% DMADDM + 10% NACP, (ii) SBMP adhesive + 5% DMADDM + 20% NACP, (iii) SBMP adhesive + 5% DMADDM + 30% NACP, (iv) SBMP adhesive + 5% DMADDM + 40% NACP. Each adhesive paste was placed into a rectangular mold of 2 × 2 × 12 mm following previous studies [42,44]. The specimen was photo-cured (Triad 2000, Dentsply, York, PA) for 1 min on each open side of the mold and then stored at 37 °C for 1 day. A sodium chloride (NaCl) solution (133 mmol/L) was buffered to three different pH: pH 4 with 50 mmol/L lactic acid, pH 5.5 with 50 mmol/L acetic acid, and pH 7 with 50 mmol/L HEPES. Following previous studies [44], three specimens of 2 × 2 × 12 mm were immersed in 50 mL of solution at each pH, yielding a specimen volume/solution of 2.9 mm3/mL. This compared to a specimen volume per solution of approximately 3.0 mm3/mL in a previous study [39]. For each solution, the concentrations of Ca and P ions released from the specimens were measured at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. At each time, aliquots of 0.5 mL were removed and replaced by fresh solution. The aliquots were analyzed for Ca and P ions via a spectrophotometric method (DMS-80 UV-visible, Varian, Palo Alto, CA) using known standards and calibration curves [39,40,42,44].

2.11. Statistical analysis

One-way and two-way analyses-of-variance (ANOVA) were performed to detect the significant effects of the variables. Tukey’s multiple comparison was used to compare the data at p of 0.05.

3. Results

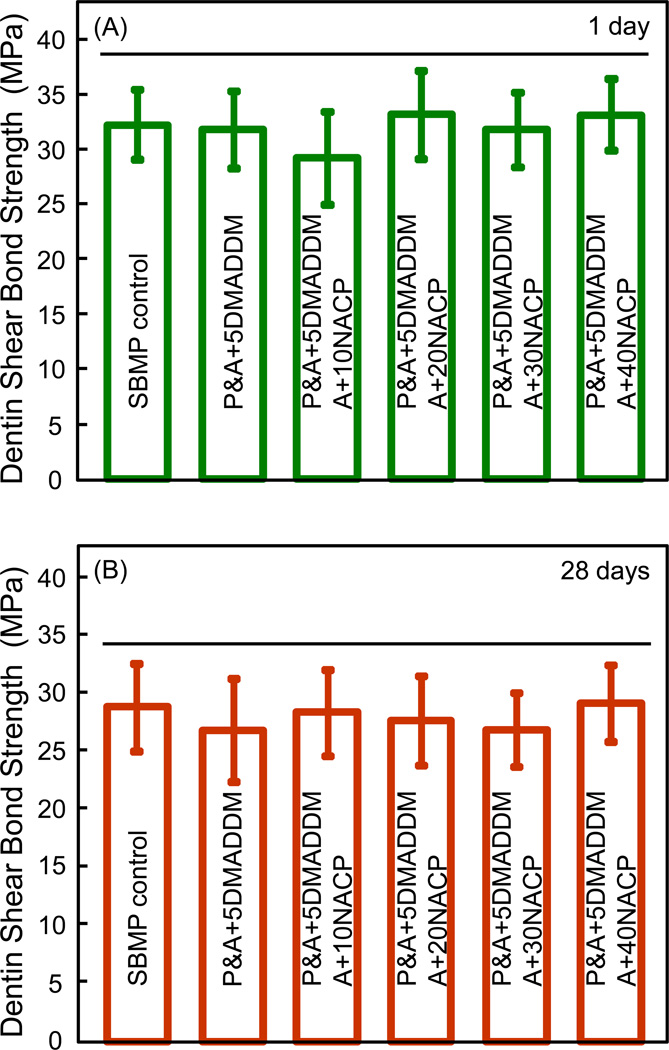

The dentin shear bond strength results are plotted in Fig. 1 after immersion for: (A) 1 day, and (B) 28 days (mean ± sd; n = 10). Adding NACP from 10% to 40% did not significantly affect the dentin bond strength, compared to SBMP control (p > 0.1). Water-aging for 28 days had no significant effect on dentin bond strength, compared to those at 1 day (p > 0.1). The mean values of dentin bond strengths at 28 days were approximately 10% lower than those at 1 day. For example, the dentin bond strength of SMBP control decreased from approximately 32 MPa at 1 day to 29 MPa at 28 days. However, the difference between 1 day and 28 days was not statistically significant (p > 0.1). Furthermore, incorporating 5% DMADDM had no significant effect on dentin bond strength, compared to SBMP control without DMADDM (p > 0.1).

Figure 1.

Dentin shear bond strength using extracted human teeth: (A) after 1 day immersion, and (B) after 28 days of immersion (mean ± sd; n = 10). Horizontal line indicates values that are not significantly different (p > 0.1). “P” designates SBMP primer. “A” designates SBMP adhesive. All values in (A) and (B) are statistically similar (p > 0.1).

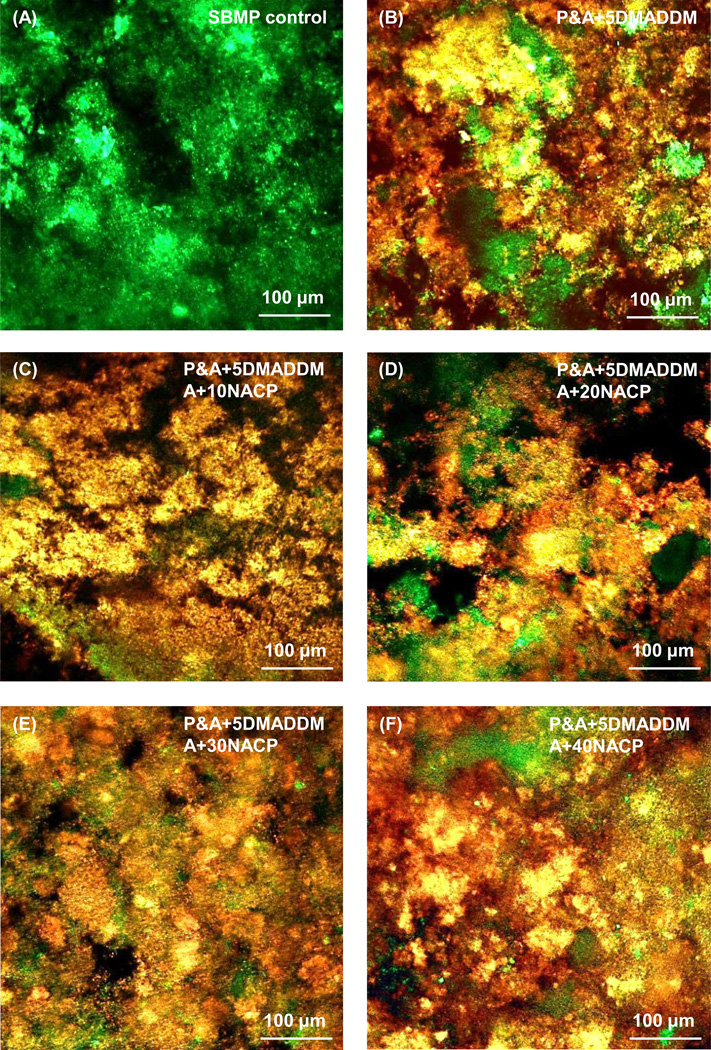

Fig. 2 shows representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of live/dead staining of 2-day biofilms on disks of the six bonding agents. SBMP control disks were covered by primarily live bacteria. In contrast, all the five groups containing DMADDM had mostly dead bacteria. Varying the NACP amount from 0% to 40% did not appear to have a noticeable effect on biofilm viability.

Figure 2.

Representative live/dead images of dental plaque microcosm biofilms grown for 2 days on: (A) SBMP control; (B) P&A + 5DMADDM; (C) P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 10NACP; (D) P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 20NACP; (E) P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 30NACP; and (F) P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 40NACP. Live bacteria were stained green, and dead bacteria were stained red. Live/dead bacteria that were close to, or on the top of, each other produced orange or yellow colors. SBMP control was covered by primarily live bacteria. The other five groups containing DMADDM had mostly dead bacteria.

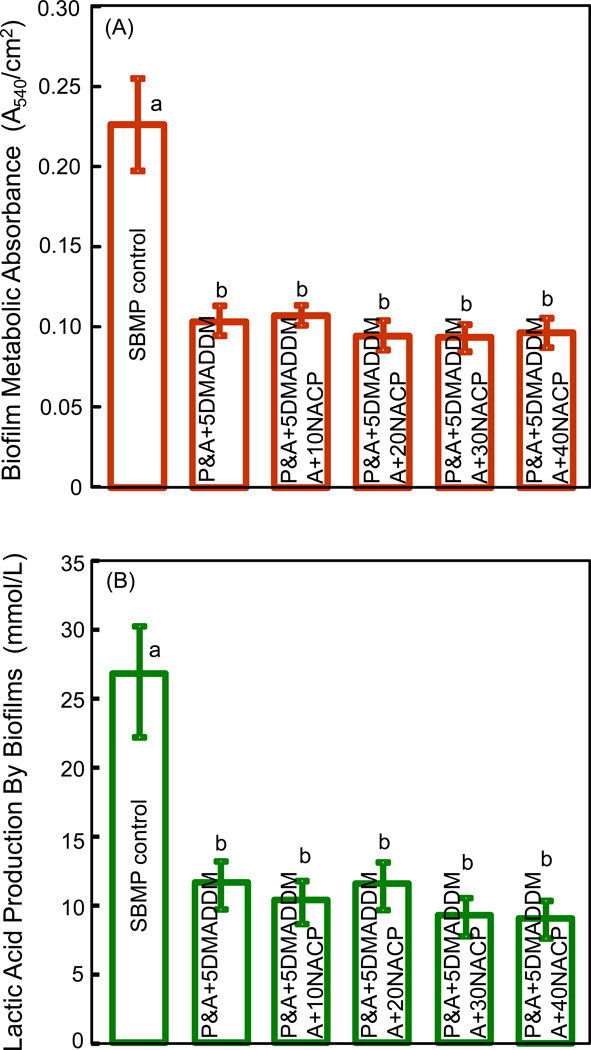

Fig. 3 shows quantitative antibacterial properties of the bonding agents: (A) Biofilm metabolic activity via the MTT assay, and (B) lactic acid production by biofilms (mean ± sd; n = 6). Adding DMADDM into bonding agent substantially decreased the biofilm metabolic activity. On the other hand, changing NACP filler level from 0% to 40% had no significant effect (p > 0.1). The lactic acid production by biofilms was also greatly reduced by DMADDM incorporation, and the antibacterial efficacy was not compromised when NACP was added into the bonding agent containing DMADDM.

Figure 3.

Dental plaque microcosm biofilm properties on bonding agents: (A) Metabolic activity via the MTT assay, and (B) lactic acid production (mean ± sd; n = 6). Six bonding agents were tested: SBMP control; P&A + 5DMADDM; P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 10NACP; P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 20NACP; P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 30NACP; and P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 40NACP. In each plot, values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

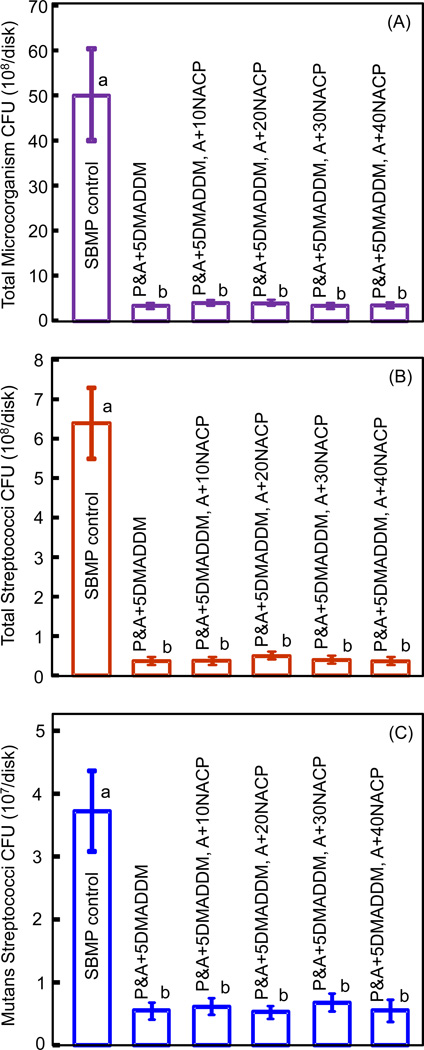

The CFU counts of biofilms adherent on the six bonding agents are plotted in Fig. 4: (A) Total microorganisms, (B) total streptococci, and (C) mutans streptococci (mean ± sd; n = 6). All five bonding agents containing DMADDM had much lower biofilm CFU than SBMP control (p < 0.05). The antibacterial potency did not change with the addition of NACP to the adhesive (p > 0.1).

Figure 4.

Colony-forming units (CFU) of 2-day biofilms on bonding agents: (A) Total microorganisms, (B) total streptococci, and (C) mutans streptococci (mean ± sd; n = 6). Six bonding agents were tested: SBMP control; P&A + 5DMADDM; P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 10NACP; P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 20NACP; P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 30NACP; and P&A + 5DMADDM, A + 40NACP. In each plot, values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

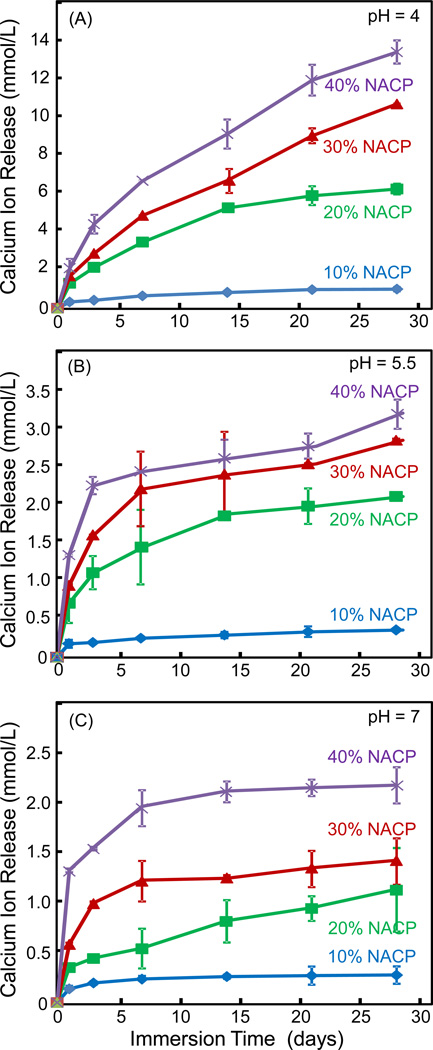

The Ca ion release from adhesive specimens vs. NACP filler level are plotted in Fig. 5 at three different pH values: (A) pH 4, (B) pH 5.5, and (C) pH 7. Note the y-scale difference in order to show the data points with clarity. Two-way ANOVA showed that NACP filler level and immersion time both had significant effects on ion release (p < 0.05), with a significant interaction between the two variables (p < 0.05). In each plot at each pH, increasing the NACP filler level in adhesive monotonically increased the Ca ion release. Decreasing the solution pH significantly increased the ion release, with Ca ion release at pH 4 being about 6 to 10 times higher than the release at pH 7.

Figure 5.

Calcium ion release from cured adhesive specimens as a function of NACP filler level: (A) pH 4, (B) pH 5.5, and (C) pH 7. Note the y-scale difference in order to show the data points with clarity. Increasing the NACP filler level from 10% to 40% increased the Ca ion release (p < 0.05). Decreasing the solution pH increased the ion release (p < 0.05).

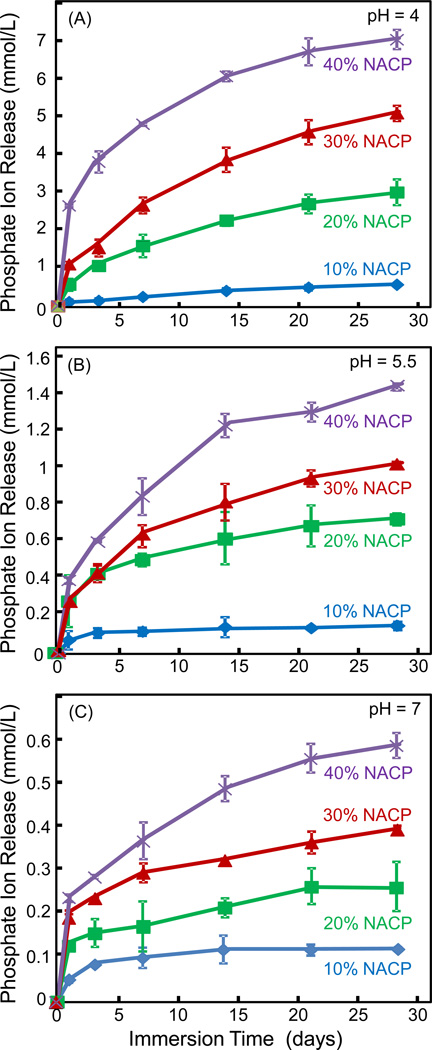

The corresponding P ion release profiles from the adhesives are plotted in Fig. 6: (A) pH 4, (B) pH 5.5, and (C) pH 7. Increasing the NACP filler level in the adhesive from 10% to 40% increased the ion release by approximately an order of magnitude. Furthermore, the P ion release was much higher at acidic pH than that at neutral pH. The released P ion concentration at pH 4 was approximately 10-fold that at pH 7.

Figure 6.

Phosphate ion release from the adhesive specimens as a function of NACP filler level: (A) pH 4, (B) pH 5.5, and (C) pH 7. Note the y-scale difference in order to show the data points with clarity. Increasing the NACP filler level in the adhesive from 10% to 40% increased the ion release. The level of ion release was increased at acidic pH (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The present study developed antibacterial bonding agents with DMADDM and NACP, and determined the effects of NACP filler level and pH on Ca and P ion release from adhesive for the first time. The bonding agent containing DMADDM and NACP had three advantages: (1) antibacterial activity to inhibit biofilm growth and lactic acid production; (2) NACP for Ca and P ion release to inhibit caries, where the release could be dramatically increased at cariogenic acidic pH; and (3) dentin bond strength matching commercial bonding agent without antibacterial or remineralizing capability. Recurrent caries at the margins limits the lifetime of composite restorations. It is beneficial to stabilize or regress caries thereby to increase the restoration longevity. In vivo demineralization occurs with the dissolution of Ca and P ions from the tooth structure into the saliva. On the other hand, remineralization occurs with mineral precipitation into the tooth structure to increase the mineral content. Although saliva contains Ca and P ions, the remineralization of tooth lesions can be significantly promoted by increasing the solution concentrations of Ca and P ions to levels higher than those in natural oral fluids. Furthermore, when marginal gaps occur at the tooth-restoration interface, a NACP adhesive could greatly increase the local Ca and P ion concentration to promote remineralization and inhibit demineralization at the margin, where secondary caries usually occurs. Therefore, an important approach to the inhibition of demineralization and the promotion of remineralization was to develop CaP-containing restorations [39–47]. Indeed, CaP-filled resins released Ca and P ions to supersaturating levels with respect to tooth mineral, which were shown to protect the teeth from demineralization, or even regenerate lost tooth mineral [46,47]. Furthermore, NACP-containing adhesive of the present study has the benefit of potentially remineralizing the remnants of lesions in the prepared tooth cavity and increasing the mineral content of enamel and dentin at the margins to provide a strong tooth-restoration interface.

The Ca and P ion release from adhesive was investigated as a function of filler level and solution pH. NACP had a specific surface area of 17.76 m2/g [44]. In comparison, the specific surface area for traditional ACP particles was about 0.5 m2/g [43]. Therefore, resins containing NACP could release more Ca and P ions using lower filler levels of NACP than traditional ACP. For adhesive, a filler level of 40% or less was used in order to not compromise the dentin bond strength. While the filler level was limited for the adhesive, the NACP with a high surface area possessed a high ion releasing capability. As a result, the Ca and P ion release levels were higher than those reported for previous CaP composites [39,40]. Increasing the NACP filler level from 10% to 40% increased the Ca and P ion release by about an order of magnitude. Therefore, clinically, 30% to 40% of NACP should be used in adhesive for maximum caries-inhibition capability. The pH was another important parameter that affects the ion release. A local plaque pH in vivo of above 6 is considered safe, pH of 6.0 to 5.5 is potentially cariogenic, and pH of 5.5 to 4 is cariogenic. The NACP adhesive was “smart” and substantially increased the Ca and P ion release when the pH was reduced from neutral to a cariogenic pH of 4. There was a 6–10 fold increase in ion release as the pH was decreased from 7 to 4, when these ions would be most-needed to inhibit caries. Further in vivo studies are required to investigate that caries-inhibition efficacy of the NACP adhesive.

In a recent study on a modified adhesive containing NACP, the bonded interface was examined in a scanning electron microscope [48]. Numerous NACP nanoparticles were found in resin tags in the dentinal tubules as well as in the hybrid layer [48]. However, SEM examination did not reveal remineralization effects of the hybrid layer or the local dentin where the resin tags containing NACP were located in. A separate study reported significant remineralization in tooth enamel via NACP using quantitative microradiography, where the mineral profiles of enamel sections were measured via contact microradiography [46]. Future study should use quantitative microradiography to measure the mineralization in dentin using the NACP adhesive. Furthermore, with Ca and P ion release, it is possible that the adhesive may be weakened mechanically over time. The present study showed a small (statistically insignificant) reduction in dentin bond strength after 28 d water-aging, compared to 1 d. This is consistent with a previous study with 6 months of water-aging, showing a slight but insignificant change in dentin bond strength compared to 1 d [49]. The small size of the NACP nanoparticles may be desirable in maintaining good mechanical properties than the use of larger traditional CaP particles in the resin matrix [41,42,44]. Further study is needed to investigate the effect of CaP particle size on the durability of dentin bond strength.

The incorporation of 5% DMADDM imparted a potent anti-biofilm capability to the NACP bonding agent. Caries is a dietary carbohydrate-modified bacterial infectious disease caused by acid production by biofilms [14,15]. Because there are often residual bacteria in the prepared tooth cavity and it is extremely difficult to completely eradicate bacteria in the tooth cavity, an antibacterial bonding agent would help kill bacteria inside dentinal tubules [25–27]. In addition, there has been an increased interest in the less removal of tooth structure and minimal intervention dentistry [56]. While this could preserve more tooth structure, this could also leave behind more carious tissues with active bacteria in the tooth cavity. Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) does not remove the carious tissues completely, leaving remnants of lesions and bacteria [57]. Using the bonding agent of the present study containing DMADDM and NACP, the NACP could remineralize the remaining tooth lesions, while the DMADDM could potentially kill the residual bacteria in the tooth cavity while the bonding agent was in the uncured state before it was photo-polymerized.

After tooth cavity restoration, during service in vivo, microgaps could form at the tooth-restoration interfaces allowing for bacterial invasion [58,59]. This could cause secondary caries at the margins and harm the pulp. Microgaps were observed between the adhesive resin and the primed dentin, or between the adhesive resin and the hybrid layer [58,59]. This would suggest that a large portion of the marginal gap is surrounded by the cured adhesive resin, hence the invading bacteria would mostly come into contact with the adhesive surface [29]. The bonding agent containing DMADDM and NACP could potentially inhibit such invading bacteria at the margins, while could also release Ca and P ions at the margins to remineralize lesions in the case of a cariogenic challenge.

QAMs possess bacteriolysis ability because their positively-charged quaternary amine N+ can attract the negatively-charged cell membrane of the bacteria, which could disrupt the cell membrane and cause cytoplasmic leakage [25,26,55]. Since the QAM was co-polymerized with and immobilized in the resin, the antibacterial effect would be durable and not leach out or be diminished over time [25,26]. Indeed, a bonding agent containing QAM was water-aged for 6 months, and there was no decrease in its antibacterial efficacy from 1 day to 6 months [49]. Furthermore, after 6 months of water-aging, there was no decrease in the dentin bond strength compared to that at 1 day [49]. This dentin bond strength durability was likely related to the antibacterial bonding agent’s inhibition of the host-derived matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which could degrade the hybrid layer [49,60]. Further studies are needed to investigate the long-term properties and the remineralization capability in vivo of the bonding agent containing DMADDM and NACP.

5. Conclusions

This study developed bonding agents containing an antibacterial monomer DMADDM as well as a remineralizer NACP, and determined the effects of NACP filler level and pH on Ca and P ion release from adhesive. Incorporating DMADDM into bonding agent yielded a potent antibacterial activity, while NACP in adhesive released Ca and P ions for remineralization and caries-inhibition. This was achieved without compromising the dentin bond strength at 1 day and 1 month. The Ca and P ion release was greatly increased with NACP filler level increasing from 10% to 40% in the adhesive. The NACP adhesive was “smart” and dramatically increased the ion release at a cariogenic pH 4, when these ions would be most-needed to inhibit caries. DMADDM imparted a strong anti-biofilm function to the bonding agent, substantially reducing metabolic activity and lactic acid of biofilm as well as total microorganisms, total streptococci and mutans streptococci of the biofilm. Therefore, the bonding agent containing DMADDM and NACP is promising for inhibiting biofilms at the margins and remineralization to combat recurrent caries, which is currently a main reason for restoration failure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Fang Li, Ke Zhang and Joseph M. Antonucci for fruitful discussions. This study was supported by NIH R01 DE17974 (HX), a scholarship from the West China School of Stomatology (CC), a bridge fund from the University of Maryland Baltimore School of Dentistry (HX), and a seed grant from the University of Maryland Baltimore (HX).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Official contribution of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); not subject to copyright in the United States.

Disclaimer

Certain commercial materials and equipment are identified to specify experimental procedures. This does not imply recommendation by NIST/ADA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drummond JL. Degradation, fatigue, and failure of resin dental composite materials. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87:710–719. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferracane JL. Resin composite - State of the art. Dental Materials. 2011;27:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demarco FF, Correa MB, Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Opdam NJM. Longevity of posterior composite restorations: Not only a matter of materials. Dental Materials. 2012;28:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satterthwaite JD, Maisuria A, Vogel K, Watts DC. Effect of resin-composite filler particle size and shape on shrinkage-stress. Dental Materials. 2012;28:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayne SC, Thompson JY, Swift EJ, Stamatiades P, Wilkerson M. A characterization of first-generation flowable composites. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1998;129:567–577. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu X, Burgess JO. Compressive strength, fluoride release and recharge of fluoride-releasing materials. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2451–2461. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00638-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts DC, Marouf AS, Al-Hindi AM. Photo-polymerization shrinkage-stress kinetics in resin-composites: methods development. Dental Materials. 2003;19:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferracane JL. Hygroscopic and hydrolytic effects in dental polymer networks. Dental Materials. 2006;22:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuel SP, Li S, Mukherjee I, Guo Y, Patel AC, Baran GR, Wei Y. Mechanical properties of experimental dental composites containing a combination of mesoporous and nonporous spherical silica as fillers. Dental Materials. 2009;25:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu H, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Impact of curing protocol on conversion and shrinkage stress. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:822–826. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coelho-De-Souza FH, Camacho GB, Demarco FF, Powers JM. Fracture resistance and gap formation of MOD restorations: influence of restorative technique, bevel preparation and water storage. Operative Dentistry. 2008;33:37–43. doi: 10.2341/07-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zalkind MM, Keisar O, Ever-Hadani P, Grinberg R, Sela MN. Accumulation of Streptococcus mutans on light-cured composites and amalgam: An in vitro study. Journal of Esthetic Dentistry. 1998;10:187–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1998.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyth N, Domb AJ, Weiss EI. An in vitro quantitative antibacterial analysis of amalgam and composite resins. Journal of Dentistry. 2007;35:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Featherstone JDB. The science and practice of caries prevention. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2000;131:887–899. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng DM, ten Cate JM. Demineralization of dentin by Streptococcus mutans biofilms grown in the constant depth film fermentor. Caries Research. 2004;38:54–61. doi: 10.1159/000073921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer P, Ye Q, Park JG, Topp EM, Misra A, Marangos O, Wang Y, Bohaty BS, Singh V, Sene F, Eslick J, Camarda K, Katz JL. Adhesive/dentin interface: The weak link in the composite restoration. Annals Biomedical Engineering. 2010;38:1989–2003. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Breschi L, Tjaderhane L, Carvalho RM, Carrilho M, Tezvergil-Mutluay A. State of the art etch-and-rinse adhesives. Dental Materials. 2011;27:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Meerbeek B, Yoshihara K, Yoshida Y, Mine A, De Munck J. State of the art of self-etch adhesives. Dental Materials. 2011;27:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roeder L, Pereira RNR, Yamamoto T, Ilie N, Armstrong S, Ferracane J. Spotlight on bond strength testing-Unraveling the complexities. Dental Materials. 2011;27:1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.08.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikemura K, Tay FR, Endo T, Pashley DH. A review of chemical-approach and ultramorphological studies on the development of fluoride-releasing dental adhesives comprising new pre-reacted glass ionomer (PRG) fillers. Dental Materials Journal. 2008;27:315–329. doi: 10.4012/dmj.27.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J, Ye Q, Topp E, Misra A, Kieweg SL, Spencer P. Water sorption and dynamic mechanical properties of dentin adhesives with a urethane-based multifunctional methacrylate monomer. Dental Materials. 2009;25:1569–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritter AV, Swift EJ, Jr, Heymann HO, Sturdevant JR, Wilder AD., Jr An eight-year clinical evaluation of filled and unfilled one-bottle dental adhesives. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2009;140:28–37. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Godoy F, Kramer N, Feilzer AJ, Frankenberger R. Long-term degradation of enamel and dentin bonds: 6-year results in vitro vs. in vivo. Dental Materials. 2010;26:1113–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J, Eslick J, Ye Q, Misra A, Spencer P. The influence of chemical structure on the properties in methacrylate-based dentin adhesives. Dental Materials. 2011;27:1086–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imazato S. Review: Antibacterial properties of resin composites and dentin bonding systems. Dental Materials. 2003;19:449–457. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imazato S. Bioactive restorative materials with antibacterial effects: new dimension of innovation in restorative dentistry. Dental Materials Journal. 2009;28:11–19. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li F, Chen J, Chai Z, Zhang L, Xiao Y, Fang M, Ma S. Effects of a dental adhesive incorporating antibacterial monomer on the growth, adherence and membrane integrity of Streptococcus mutans. Journal of Dentistry. 2009;37:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Namba N, Yoshida Y, Nagaoka N, Takashima S, Matsuura-Yoshimoto K, Maeda H, Van Meerbeek B, Suzuki K, Takashida S. Antibacterial effect of bactericide immobilized in resin matrix. Dental Materials. 2009;25:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imazato S, Kinomoto Y, Tarumi H, Ebisu S, Tay FR. Antibacterial activity and bonding characteristics of an adhesive resin containing antibacterial monomer MDPB. Dental Materials. 2003;19:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imazato S, Kuramoto A, Takahashi Y, Ebisu S, Peters MC. In vitro antibacterial effects of the dentin primer of Clearfil Protect Bond. Dental Materials. 2006;22:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie D, Weng Y, Guo X, Zhao J, Gregory RL, Zheng C. Preparation and evaluation of a novel glass-ionomer cement with antibacterial functions. Dental Materials. 2011;27:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Agee KA, Uchiyama T, Imazato S, Mutluay MM, Cadenaro M, Breschi L, Nishitani Y, Tay FR, Pashley DH. The inhibitory effects of quaternary ammonium methacrylates on soluble and matrix-bound MMPs. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90:535–540. doi: 10.1177/0022034510389472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonucci JM, Zeiger DN, Tang K, Lin-Gibson S, Fowler BO, Lin NJ. Synthesis and characterization of dimethacrylates containing quaternary ammonium functionalities for dental applications. Dental Materials. 2012;28:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Wang Y, Liao S, Wen ZT, Fan Y. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial dental monomers and composites. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2012;100:1511–1162. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weng Y, Howard L, Guo X, Chong VJ, Gregory RL, Xie D. A novel antibacterial resin composite for improved dental restoratives. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2012;23:1553–1561. doi: 10.1007/s10856-012-4629-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng L, Weir MD, Xu HHK, Antonucci JM, Kraigsley AM, Lin NJ, Lin-Gibson S, Zhou XD. Antibacterial amorphous calcium phosphate nanocomposite with quaternary ammonium salt and silver nanoparticles. Dental Materials. 2012;28:561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng L, Zhang K, Melo MAS, Weir MD, Zhou XD, Xu HHK. Anti-biofilm dentin primer with quaternary ammonium and silver nanoparticles. Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91:598–604. doi: 10.1177/0022034512444128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng L, Weir MD, Zhang K, Arola DD, Zhou X, Xu HHK. Dental primer and adhesive containing a new antibacterial quaternary ammonium monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate. Journal of Dentistry. 2013;41:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skrtic D, Antonucci JM, Eanes ED. Improved properties of amorphous calcium phosphate fillers in remineralizing resin composites. Dental Materials. 1996;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(96)80037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickens SH, Flaim GM, Takagi S. Mechanical properties and biochemical activity of remineralizing resin-based Ca-PO4 cements. Dental Materials. 2003;19:558–566. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu HHK, Sun L, Weir MD, Antonucci JM, Takagi S, Chow LC. Nano dicalcium phosphate anhydrous-whisker composites with high strength and Ca and PO4 release. Journal of Dental Research. 2006;85:722–727. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu HHK, Weir MD, Sun L, Takagi S, Chow LC. Effect of calcium phosphate nanoparticles on Ca-PO4 composites. Journal of Dental Research. 2007;86:378–383. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langhorst SE, O’Donnell JNR, Skrtic D. In vitro remineralization of enamel by polymeric amorphous calcium phosphate composite: Quantitative microradiographic study. Dental Materials. 2009;25:884–891. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.01.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu HHK, Moreau JL, Sun L, Chow LC. Nanocomposite containing amorphous calcium phosphate nanoparticles for caries inhibition. Dental Materials. 2011;27:762–769. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreau JL, Sun L, Chow LC, Xu HHK. Mechanical and acid neutralizing properties and inhibition of bacterial growth of amorphous calcium phosphate dental nanocomposite. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2011;98:80–88. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weir MD, Chow LC, Xu HHK. Remineralization of demineralized enamel via calcium phosphate nanocomposite. Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91:979–984. doi: 10.1177/0022034512458288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melo MAS, Weir MD, Rodrigues LKA, Xu HHK. Novel calcium phosphate nanocomposite with caries-inhibition in a human in situ model. Dental Materials. 2013;29:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melo MAS, Cheng L, Zhang K, Weir MD, Rodrigues LKA, Xu HHK. Novel dental adhesives containing nanoparticles of silver and amorphous calcium phosphate. Dental Materials. 2013;29:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang K, Cheng L, Wu EJ, Weir MD, Bai Y, Xu HHK. Effect of water-aging on dentin bond strength and anti-biofilm activity of bonding agent containing antibacterial monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate. Journal of Dentistry. 2013;41:504–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McBain AJ. In vitro biofilm models: an overview. Advances in Applied Microbiology. 2009;69:99–132. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imazato S, Ehara A, Torii M, Ebisu S. Antibacterial activity of dentine primer containing MDPB after curing. Journal of Dentistry. 1998;26:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McBain AJ, Sissons C, Ledder RG, Sreenivasan PK, De Vizio W, Gilbert P. Development and characterization of a simple perfused oral microcosm. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;98:624–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kraigsley AM, Tang K, Howarter JA, Lin-Gibson S, Lin NJ. Effect of polymer degree of conversion on Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2012;12:1706–1713. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201200214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shewmaker PL, Gertz RE, Jr, Kim CY, de Fijter S, DiOrio M, Moore MR, et al. Streptococcus salivarius meningitis case strain traced to oral flora of anesthesiologist. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48:2589–2591. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00426-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lima JP, Sampaio de Melo MA, Borges FM, Teixeira AH, Steiner-Oliveira C, Nobre Dos Santos M, et al. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of photodynamic antimicrobial therapy in an in situ model of dentine caries. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2009;117:568–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lynch CD, Frazier KB, McConnell RJ, Blum IR, Wilson NH. Minimally invasive management of dental caries: contemporary teaching of posterior resin-based composite placement in U.S. and Canadian dental schools. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2011;142:612–620. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frencken JE, van't Hof MA, van Amerongen WE, Holmgren CJ. Effectiveness of single-surface ART restorations in the permanent dentition: a meta-analysis. Journal of Dental Research. 2004;83:120–123. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duarte SJ, Lolato AL, de Freitas CR, Dinelli W. SEM analysis of internal adaptation of adhesive restorations after contamination with saliva. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry. 2005;7:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loguercio AD, Reis A, Bortoli G, Patzlaft R, Kenshima S, Rodrigues Filho LE, et al. Influence of adhesive systems on interfacial dentin gap formation in vitro. Operative Dentistry. 2006;31:431–441. doi: 10.2341/05-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Agee KA, Uchiyama T, Imazato S, Mutluay MM, Cadenaro M, et al. The inhibitory effects of quaternary ammonium methacrylates on soluble and matrix-bound MMPs. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90:535–540. doi: 10.1177/0022034510389472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]