Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the relationship between body composition indicators, including body mass index (BMI), fat mass index (FMI) and lean BMI (LBMI), and adverse outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in Asian populations. The aim of this study was to clarify this relationship.

Methods

The SHINANO registry is a prospective, observational, multicenter cohort registry that enrolled 1923 consecutive patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) from August 2012 to July 2013; 66 patients were excluded because of missing data. We evaluated 1857 patients with CHD who underwent PCI (aged 70±11 years; 23% women; BMI 23.8±3.5 kg/m2; LBMI 18.3±1.8 kg/m2; FMI 5.4±2.2 kg/m2). Patients were divided into three groups, based on BMI, LBMI and FMI tertiles, to assess the prognostic value of the three indicators. The primary endpoint was major adverse cardiac events (MACE), including all cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke at 1 year.

Results

Over a 1 year follow-up period (1776 patients, 95.6%), the cumulative MACE incidence was 8.7% (161 cases). Using Kaplan–Meier analysis, the MACE incidence was significantly higher in patients with lower BMI values (13.4–22.2 kg/m2) (p=0.002) and lower LBMI values (11.6–17.6 kg/m2) (p<0.001); this trend was not observed for FMI. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that lower LBMI but not lower BMI values were predictive of a higher MACE incidence (HR 1.55; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.30).

Conclusions

Lower LBMI values are associated with adverse outcomes in an Asian population with CHD undergoing PCI. LBMI is a better predictor of MACE than BMI or FMI.

Clinical trial registration

UMIN-ID; 000010070.

Keywords: CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Introduction

Obesity is a well known mortality risk factor among the general population,1 and has been described as one the most visible yet neglected public health problems.2 Obesity is commonly assessed by body mass index (BMI), with underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2) individuals having a higher incidence of coronary artery disease.3 In particular, higher levels of obesity (BMI ≥35.0 kg/m2) are significantly associated with a higher incidence of all cause mortality.4 Although BMI is a simple tool for assessing obesity, differentiating fat mass (FM) content from skeletal muscle mass, or lean body mass (LBM), is difficult using the BMI calculation, especially in patients with a BMI value <30 kg/m2.5 Therefore, BMI assessment may misclassify individuals with excess adipose tissue as being non-obese. Sex, age and race have also been reported to alter the relationship between BMI and mortality.6

A previous report demonstrated an inverse correlation between LBM and mortality risk.7 However, LBM dynamically decreases with advancing age, even when BMI remains stable. The incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) is also well known to increase with age. Therefore, we hypothesised that the LBM index (LBMI) might be a better prognostic predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) than conventional predictors, including BMI, in patients with CHD.

In the current study, we evaluated the relationship of body composition parameters, including BMI, LBMI and FM index (FMI), with adverse clinical events in an Asian population with CHD who had undergone percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).

Methods

Study populations

A retrospective subanalysis was performed using integrated data for the period August 2012 to July 2013 from the Shinshu Prospective Multicentre Analysis for Elderly Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (SHINANO) registry. The SHINANO registry design has been described in detail previously.8 Briefly, this registry is a prospective, multicenter, observational registry of patients with any CHD, including stable angina, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI and unstable angina, who underwent PCI at one of 16 collaborating hospitals in the Nagano prefecture of Japan. This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry, as accepted by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (UMIN-ID; 000010070). The registry did not have any exclusion criteria, and was an all comer registry. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of each participating hospital. All patients gave written informed consent before participating.

Among the 1923 patients registered in the SHINANO registry, we identified 1857 patients who had body height and weight data recorded. Patients were prospectively followed for 1 year. The primary endpoint of this study was incidence of MACE, including all cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) and ischaemic stroke. The relationship between the anthropometric measurements (BMI, FMI and LBMI) and the incidence of MACE was analysed.

Definitions

Body weight was measured using a digital scale to the nearest 0.01 kg, and height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer while patients stood without shoes. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). LBM was calculated using the James formula as follows: in men, LBM=(1.1×weight (kg))−(128×(weight (kg)/height (cm))2); in women, LBM=(1.07×weight (kg))−(148×(weight (kg)/height (cm))2).9 FM was calculated as LBM (kg) subtracted from body weight (kg). LBMI and FMI were calculated as LBM and FM (kg), divided by the height squared (m2).

Non-fatal MI was defined as a twofold or greater in increase in creatine phosphokinase concentration, troponin-T levels ≥0.1 ng/mL or new Q waves in ≥2 contiguous electrocardiogram leads.10 Ischaemic stroke was defined as the presence of a new neurological deficit, lasting for at least 24 h, with definite evidence of ischaemia on MRI or CT.11 Heart failure was based on a previous diagnosis, hospitalisation history or current heart failure treatment. Diabetes was defined as glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C) ≥6.5%, fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or treatment with hypoglycaemic agents. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or ongoing therapy for hypertension. Dyslipidaemia was defined as a serum total cholesterol concentration ≥220 mg/dL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration ≥140 mg/dL or current lipid lowering therapy.12 Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed by echocardiography using the Teichholz method, and LVEF ≤40% indicated left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction.13 All PCI procedures and selection of medical treatments after PCI were at the discretion of the treating physician.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD, if normally distributed, and as medians (IQR) if not normally distributed. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk W test. Categorical variables are described as numbers and percentages. Clinical data were described and compared across the LBMI groups. Differences between the LBMI groups were analysed using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. The Kaplan–Meier test was performed to assess the cumulative incidence of MACE, stratified by BMI, LBMI and FMI tertiles. The log rank test was used to compare survival curves. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to estimate the independent predictors of MACE; variables clinically associated with MACE were entered into the multivariate model. The variance inflation factor was used to evaluate multicollinearity for each variable; no variance inflation factor values were >2. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, V.21 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for all patients and for the three LBMI groups are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by lean body mass index tertiles

| LBMI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All patients(n=1857) | 11.7–17.6 (n=635) | 17.7–19.1 (n=621) | 19.2–23.6 (n=601) | p Value |

| Age (years) | 70.6±10.9 | 74.2±10.2 | 70.8±9.8 | 66.0±11.1 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥75 years | 718 (38.7) | 344 (54.2) | 233 (37.5) | 141 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Female | 436 (23.5) | 331 (52.1) | 99 (15.9) | 6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8±3.6 | 20.6±2.3 | 23.7±2.2 | 27.1±2.7 | <0.001 |

| BMI <18.5 kg/m2 | 97 (5.2) | 97 (15.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2 | 91 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 12 (1.9) | 79 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| FMI (kg/m2) | 5.4±2.2 | 4.3±1.7 | 5.3±2.1 | 6.8±1.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1347 (72.5) | 442 (69.6) | 429 (69.1) | 476 (79.2) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1107 (59.6) | 336 (52.9) | 355 (57.2) | 416 (69.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 108.1±35.4 | 105.5±35.9 | 106.9±32.1 | 112.0±37.7 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 47.9±13.8 | 51.3±14.9 | 47.4±13.2 | 45.0±12.6 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 685 (36.9) | 198 (31.2) | 238 (38.3) | 249 (41.4) | 0.001 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.5±5.6 | 6.4±6.5 | 6.7±7.1 | 6.4±1.3 | 0.711 |

| History of smoking | 948 (51.1) | 223 (35.1) | 326 (52.5) | 399 (66.4) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 61.4±23.7 | 58.5±26.9 | 63.4±21.8 | 62.6±21.7 | <0.001 |

| Haemodialysis | 112 (6.0) | 57 (8.9) | 25 (4.0) | 30 (4.9) | 0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7±2.0 | 12.9±4.1 | 14.6±9.6 | 14.4±1.9 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 60.2±13.4 | 59.2±14.3 | 61.2±13.1 | 60.3±12.6 | 0.056 |

| LV dysfunction | 149 (8.0) | 65 (10.2) | 44 (7.1) | 40 (6.7) | 0.034 |

| AF | 200 (10.8) | 81 (12.8) | 58 (9.3) | 61 (10.1) | 0.126 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Stroke | 181 (9.7) | 84 (13.2) | 49 (7.9) | 48 (7.9) | 0.001 |

| PAD | 198 (10.7) | 97 (15.3) | 59 (9.5) | 42 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| History of MI | 465 (25.0) | 138 (21.7) | 159 (25.6) | 168 (27.9) | 0.038 |

| ACS on admission | 816 (43.9) | 309 (48.2) | 259 (41.7) | 248 (4.13) | 0.014 |

| De novo lesion | 1648 (87.1) | 577 (90.9) | 551 (88.7) | 520 (86.5) | 0.053 |

| ISR of DES | 83 (4.5) | 21 (3.3) | 26 (4.2) | 36 (5.9) | 0.067 |

| ISR of BMS | 122 (6.6) | 40 (6.3) | 39 (6.3) | 43 (7.2) | 0.770 |

| Lesion distribution | |||||

| LAD | 871 (46.9) | 293 (46.2) | 296 (47.7) | 282 (46.9) | 0.864 |

| LCX | 351 (18.9) | 121 (19.1) | 106 (17.1) | 124 (20.6) | 0.280 |

| RCA | 686 (36.9) | 231 (36.9) | 235 (37.8) | 220 (36.6) | 0.847 |

| LMT | 43 (2.4) | 21 (3.3) | 8 (1.3) | 14 (2.3) | 0.059 |

| Bypass graft | 22 (1.2) | 10 (1.6) | 8 (1.3) | 4 (0.7) | 0.322 |

| Multivessel disease | 727 (39.1) | 257 (40.4) | 249 (40.1) | 221 (36.8) | 0.338 |

| Procedure success | 1719 (92.6) | 592 (93.2) | 578 (93.1) | 549 (91.3) | 0.380 |

| Medications | |||||

| Aspirin | 1771 (95.4) | 597 (94.0) | 596 (95.9) | 578 (96.2) | 0.728 |

| Thienopyridines | 1638 (88.2) | 546 (85.9) | 554 (89.2) | 538 (89.5) | 0.365 |

| Statins | 1305 (70.3) | 416 (65.5) | 424 (68.3) | 465 (77.4) | <0.001 |

| ACE-I | 569 (30.6) | 195 (30.7) | 189 (30.4) | 185 (30.8) | 0.967 |

| ARB | 673 (36.2) | 207 (32.6) | 200 (32.2) | 266 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| β-blockers | 673 (36.2) | 236 (37.2) | 262 (42.2) | 255 (42.4) | 0.157 |

| Warfarin | 165 (8.9) | 72 (11.3) | 67 (10.8) | 66 (10.9) | 0.917 |

Data are shown as mean±SD or n (%).

ACE-I, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BMS, bare metal stent; CVD, cerebral vascular disease; DES, drug eluting stent; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FMI, fat mass index; HbA1C, glycated haemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; ISR, in-stent restenosis; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LBMI, lean body mass index; LCX, left circumflex artery; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LMT, left main trunk; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease; RCA, right coronary artery.

Mean patient age was 70.6 years, 76.5% were men and mean BMI was 23.8 kg/m2 (range 13.4–40.8 kg/m2). Based on WHO definitions, 4.9% of subjects were obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2), 28.1% were overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), 61.8% were normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) and 5.2% were underweight (BMI <1.5 kg/m2). Among the traditional coronary risk factors, approximately 75% of patients had hypertension, 50% had dyslipidaemia, 40% had diabetes and 50% had a history of smoking. The group with low LBMI values (11.7–17.6 kg/m2) had a high proportion of patents who were older and/or were women. Patients in this group also were more likely to have LV dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, a history of stroke or peripheral artery disease (PAD) and acute coronary syndrome on admission. Concomitant atherosclerotic risk factors, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and smoking, were lower in patients with a low LBMI (11.7–17.6 kg/m2). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum haemoglobin levels were lower in patients with low LBMI values than in those with intermediate (17.7–19.1 kg/m2) or high (19.2–23.6 kg/m2) LBMI values.

To assess the strength of the relationship between LBMI and variables such as age, BMI, eGFR, LVEF, low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, we performed multiple regression analysis using the backward stepwise method. The standardised regression coefficient values for age, BMI and high density lipoprotein cholesterol were −0.105, 0.834 and −0.086, respectively.

Incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events

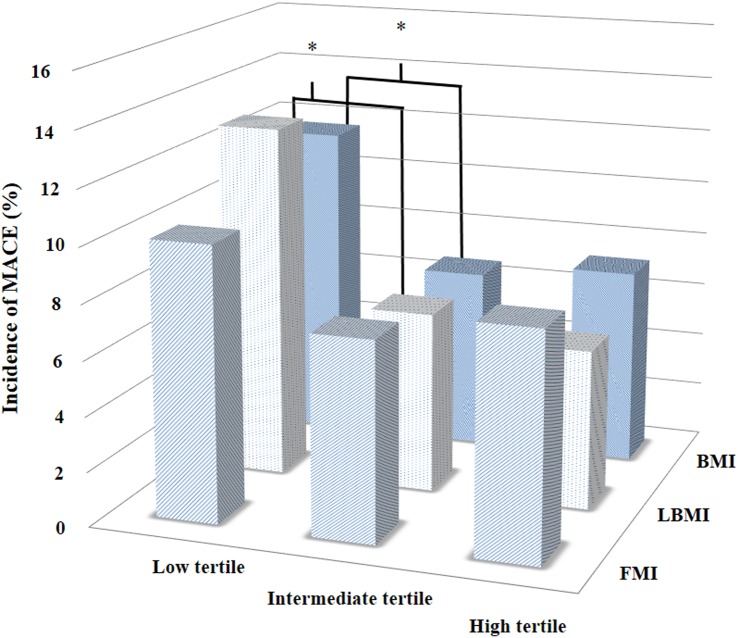

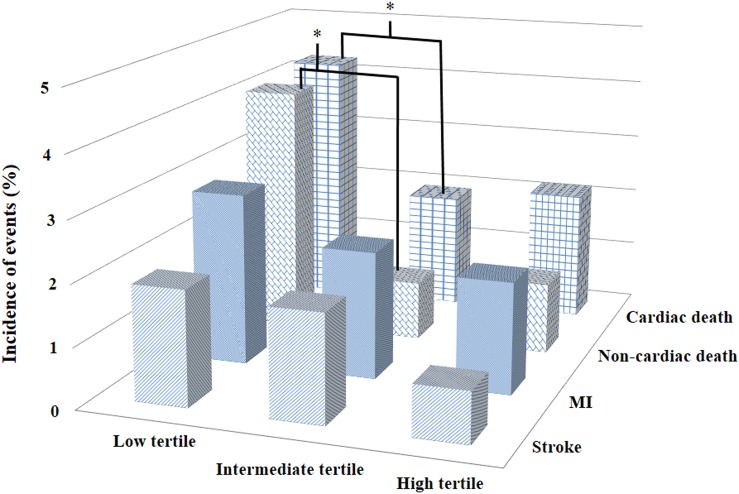

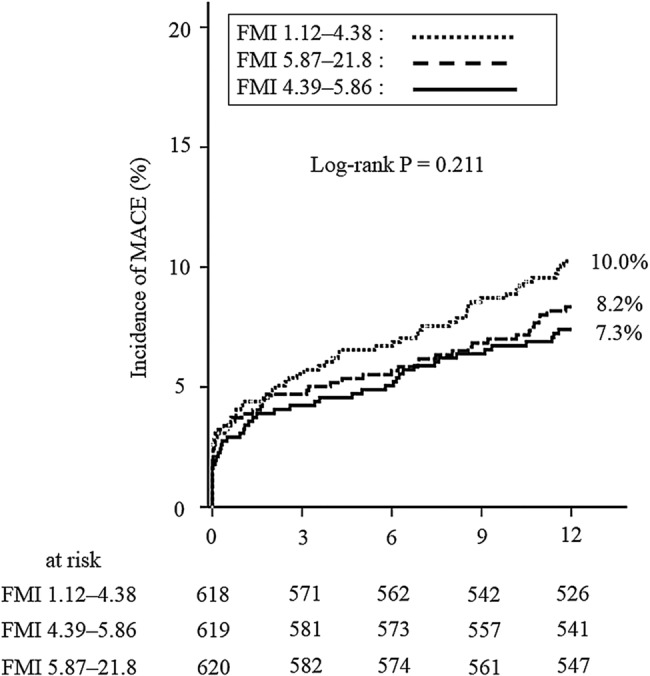

Of 1857 patients, 1776 (95.6%) completed the 1 year follow-up. During the follow-up period, 161 cases (8.7%) of MACE occurred, including 91 all cause deaths, 42 non-fatal MIs and 28 ischaemic strokes. Figure 1 illustrates the cumulative incidence of MACE according to each BMI, FMI and LBMI tertile. The lower BMI and LBMI tertiles were more often associated with adverse clinical outcomes than the intermediate or higher tertiles (χ2 test for linear trend, p=0.003 and p<0.001, respectively). This trend was not present in the FMI tertiles. Figure 2 demonstrates the difference in each clinical event, according to LBMI tertile. The incidences of cardiac and non-cardiac deaths were significantly higher in patients with lower LBMI values than in those with intermediate or high LBMI values (χ2 for linear trend, p=0.023 and p<0.001, respectively). There were no significant differences in the incidences of ischaemic stroke and MI (χ2 for linear trend, p=0.251 and p=0.466, respectively).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) according to body mass index (BMI), fat mass index (FMI) and lean BMI (LBMI) tertiles. Patients with a BMI of 13.4–22.2 kg/m2 and a LBMI of 11.7–17.6 kg/m2 had a significantly higher incidence of MACE compared with patients having other BMI and LBMI values (χ2 test for linear trend p=0.003 and p<0.001, respectively).

Figure 2.

Incidence of clinical events according to lean body mass index (LBMI) tertile. Patients with a LBMI of 11.7–17.6 kg/m2 had a significantly higher incidence of cardiac and non-cardiac deaths compared with those with intermediate or high LBMI values (χ2 test for linear trend p=0.023 and p<0.001, respectively). MI, myocardial infarction.

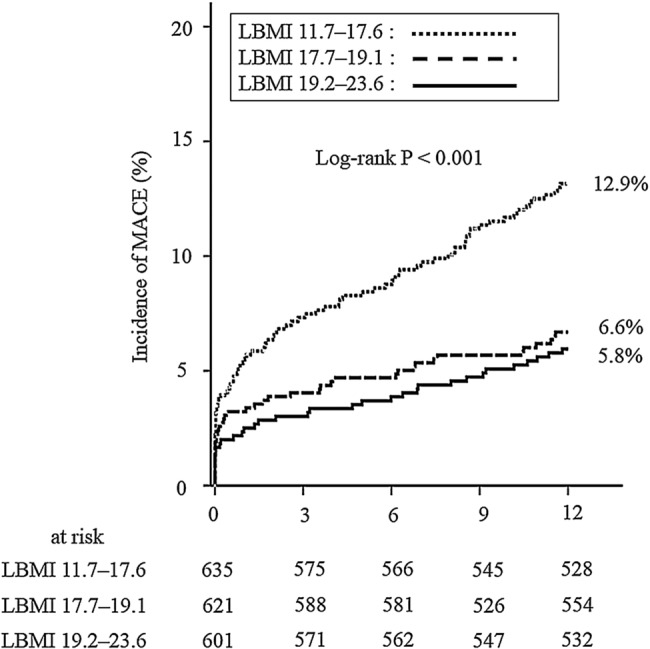

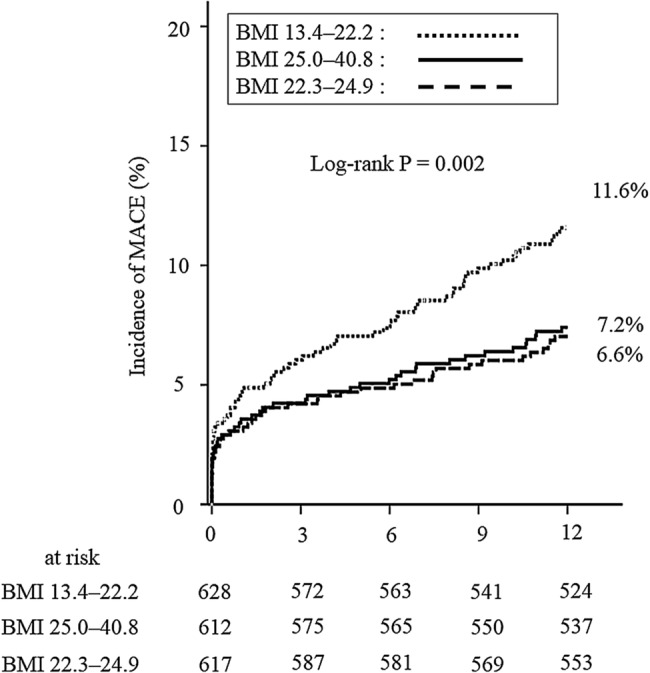

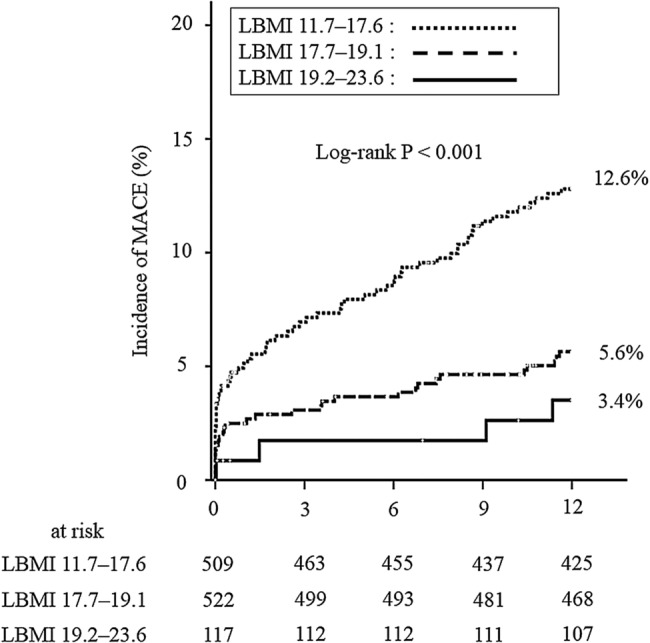

To assess the relationship between MACE and BMI, FMI and LBMI, we performed Kaplan–Meier analyses according to each anthropometric measurement. Patients with low BMI values (13.4–22.2 kg/m2) had a significantly higher incidence of MACE than those with intermediate (22.3–24.9 kg/m2) or high (25.0–40.8 kg/m2) BMI values (11.6% vs 6.6% vs 7.2%, log rank p=0.002). Patients with low LBMI values (11.7–17.6 kg/m2) also had a significantly higher incidence of MACE than those with intermediate (17.7–19.1 kg/m2) or high (19.2–23.6 kg/m2) LBMI values (12.9% vs 6.6% vs 5.8%, log rank p<0.001), as shown in figures 3 and 4. This trend was not observed in the Kaplan–Meier analysis of FMI (figure 5).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) stratified by lean body mass index (LBMI) tertile. Patients with a LBMI of 11.7–17.6 kg/m2 had a significantly higher incidence of MACE than those with intermediate (17.7–19.1 kg/m2) or high (19.2–23.6 kg/m2) LBMI values (12.9% vs 6.6% vs 5.8%, log rank p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) stratified by body mass index (BMI) tertile. Patients with a BMI of 13.4–22.2 kg/m2 had a significantly higher incidence of MACE than those with intermediate (22.3–24.9 kg/m2) or high (25.0–40.8 kg/m2) BMI values (11.6% vs 6.6% vs 7.2%, log rank p=0.002).

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) stratified by fat mass index (FMI) tertile. There were no significant differences in MACE across patients with low (1.12–4.38 kg/m2), intermediate (4.39–5.86 kg/m2) or high (5.87–21.8 kg/m2) FMI values (10.0% vs 7.3% vs 8.2%, log rank p=0.211).

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to identify the specific predictors of MACE in the study population. After adjusting for age, sex, eGFR, LV systolic dysfunction, a history of cerebral infarction or PAD, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndrome, a low LBMI (11.7–17.6 kg/m2) was an independent predictor of MACE (HR 1.51; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.24; p=0.043). In the same multivariate models, a low BMI (13.4–22.2 kg/m2) was not associated with MACE (HR 1.37; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.95; p=0.075) (table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of MACE in the overall study population

| Univariate analysis |

Model 1* |

Model 2† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Age | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 1.78 (1.29 to 2.47) | 0.001 | 1.48 (1.02 to 2.15) | 0.039 | ||

| eGFR | 0.98 (0.83 to 0.99) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.89 to 0.99) | 0.007 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.005 |

| LVD | 3.21 (2.16 to 4.78) | <0.001 | 2.81 (1.86 to 4.26) | <0.001 | 2.90 (1.92 to 4.39) | <0.001 |

| MI | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.66) | 0.374 | ||||

| Stroke | 2.20 (1.47 to 3.29) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.05 to 2.54) | 0.029 | 1.63 (1.05 to 2.54) | 0.031 |

| PAD | 1.86 (1.24 to 2.79) | 0.003 | ||||

| HTN | 1.12 (0.78 to 1.60) | 0.539 | ||||

| DLp | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.89) | 0.008 | ||||

| DM | 0.90 (0.65 to 1.25) | 0.538 | ||||

| AF | 2.01 (1.35 to 2.99) | 0.001 | ||||

| ACS | 1.55 (1.23 to 2.12) | 0.007 | 1.62 (1.15 to 2.28) | 0.006 | 1.63 (1.16 to 2.29) | 0.005 |

| LBMI 11.7–17.6 | 2.15 (1.57 to 2.93) | <0.001 | 1.51 (1.01 to 2.25) | 0.043 | ||

| BMI 13.4–22.2 | 1.73 (1.27 to 2.36) | 0.001 | 1.37 (0.97 to 1.95) | 0.075 | ||

*Model 1 included LBMI 11.7–17.6 kg/m2, age, gender, eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), LV dysfunction, history of stroke, history of PAD, hypertension, DLp, DM, AF and ACS on admission.

†Model 2 included BMI 13.4–22.2 kg/m2, age, gender, eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), LVD, history of stroke, history of PAD, hypertension, DLp, DM, AF and ACS on admission.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; DLp, dyslipidaemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertension; LBMI, lean body mass index; LVD, left ventricular dysfunction; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Clinical validation of LBMI in patients with a normal BMI

In the current study, more than half (61.8%) of patients had a normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2). To assess the clinical validation of LBMI in patients with a normal BMI, we performed Kaplan–Meier analysis according to MACE stratified by LBMI tertile (11.7–17.6 kg/m2, 17.7–19.1 kg/m2 and 19.2–23.6 kg/m2). In the subgroup of patients with a normal BMI, patients with a low LBMI (11.7–17.6 kg/m2) had a significantly higher incidence of MACE than those with an intermediate (17.7–19.1 kg/m2) or high (19.2–23.6 kg/m2) LBMI (12.6% vs 5.6% vs 3.4%, log rank p<0.001), as shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier analysis according to major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) stratified by lean body mass index (LBMI) tertile in patients with a normal body mass index. Patients with a low LBMI (11.7–17.6 kg/m2) had a significantly higher incidence of MACE than those with intermediate (17.7–19.1 kg/m2) or high (19.2–23.6 kg/m2) LBMI values (12.6% vs 5.6% vs 3.4%, log rank p<0.001).

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that a low LBMI could predict MACE in patients with CHD who had undergone PCI. In particular, patients with a LBMI of 11.7–17.6 kg/m2 had a higher incidence of MACE than those with an intermediate (17.7–19.1 kg/m2) or high (19.2–23.6 kg/m2) LBMI. Patients with a BMI of 13.4–22.2 kg/m2 also had a higher incidence of MACE; however, a BMI within this range was not an independent predictor of MACE in multivariate Cox regression analysis. Our results indicate that the assessment of LBMI provides further insight into risk stratification, following revascularisation, in patients with CHD compared with risk stratification using only BMI.

BMI is the most frequently reported tool for determining under/overweight and obesity, and a relationship between BMI and CHD patient prognosis has been established.14 Nevertheless, BMI has also been reported to be poor in distinguishing body fat from LBM.15 A recent study showed that estimation of body fat using BMI underestimated or overestimated true body fat in nearly half of patients with CHD.16 The relationship between BMI and mortality is especially variable in elderly patients;17 furthermore, BMI does not account for patient sex.18 Previous studies have also reported an increased cardiovascular risk in patients with normal weight obesity, defined as patients with a normal BMI in conjunction with elevated adiposity.19 Similarly, the waist to hip ratio has been demonstrated as a useful predictor of mortality and cardiovascular disease in Caucasian populations.20 However, neither waist circumference nor waist to hip ratio was associated with mortality in Asian populations.21

Assessment of body shape may not always contribute to adverse event prediction in all races. During the past decade, the impact of body fat and LBM on mortality has been assessed to identify body composition parameters that are more effective for predicting mortality. Navaneethan et al22 reported that a higher LBM, which was measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, was associated with lower mortality in patients without chronic kidney disease. Lavie et al23 demonstrated that lean mass index and body fat, measured using skinfold methods, predicted mortality in patients with stable CHD. They also showed that higher fat levels are associated with a better prognosis in CHD.24 However, previous studies have not reported that LBMI is useful in predicting mortality in patients with CHD, including those with stable angina, unstable angina, STEMI and non-STEMI.

We observed a relationship between LBMI and MACE in patients undergoing PCI, whereas BMI and FMI were not individually associated with MACE, in this population. This result is consistent with previous reports describing body composition and survival in patients with stable CHD.25 Thus evaluating LBMI, rather than BMI, may be important for risk stratification in patients with CHD. In this study, the mean BMI value was 23.8±3.5 kg/m2, which is similar to previous research studies in Asian populations;21 therefore, our results may be representative of the general population. An analysis of patients with normal BMI values, which accounted for more than half of the study population, showed that a low LBMI was also associated with poor clinical outcomes compared with intermediate or high LBMI values. Thus stratification using LBMI, in patients with normal BMIs, may be more useful for predicting clinical outcomes.

Although concomitant atherosclerotic risk factors were fewer in patients with a lower LBMI, the number of patients with a prior history of stroke or PAD was higher in these patients than in those with a higher BMI. In a recent study, Huang et al26 showed that low LBMI values predicted mortality in an Asian population with CAD. Similar to the result of Huang et al, our results demonstrated that a lower LBMI was an independent predictor of adverse events, after adjusting for concomitant atherosclerotic risk factors and atherosclerotic disease. A lower LBMI may be a risk factor for atherosclerotic disease although this putative relationship requires further evaluation in larger numbers of patients.

A non-significant association has been reported between BMI and mortality in elderly patients (≥65 years), and the relationship between BMI and mortality in elderly patients has been demonstrated to be represented by a U-shaped curve with a large flat bottom.27 In our population, the proportion of patients ≥65 years of age was high (72.3%), and only 4.9% of patients had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

LBMI is clinically beneficial for detecting patients with sarcopenia, defined as an age related decline in LBM and muscle strength.28 This condition has been reported to be associated with muscle loss, obesity and insulin resistance because of increased visceral fat, which promotes cardiovascular disease29 and a high incidence of mortality.30 In the assessment of standardised regression coefficients, LBMI was not strongly dependent on age, which demonstrated significant differences between LBMI tertiles. Therefore, measurement of LBMI provides additional prognostic value to the risk stratification.

Limitations

In the current study, LBM was calculated using the James formula, rather than being assessed using resistance measurement or dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. However, the James formula has been reported to perform satisfactorily in normal and moderately obese patients. In the study population, the proportion of patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 was only 4.9%. Therefore, our results were not affected by the LBM measurement. Only patients diagnosed with CAD were included in this study; our results may not apply to the normal population. An assessment of the prognostic value of the LBMI in the general population is warranted.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that stratification using LBMI may help to predict adverse events in patients with CHD who have undergone PCI. Further long term and multiracial studies in larger populations are needed to assess the clinical validation of LBMI with regard to long term outcomes and in the general population.

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

The association between body mass index (BMI) and prognosis has been studied in patients with coronary artery disease. However, age, gender and race were reported to alter this association. Body mass is composed of fat body mass and lean body mass. Lean body mass was reported to be inversely associated with mortality in Caucasian populations.

What does this study add?

A low lean BMI (LBMI) was an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in an Asian population who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention for coronary artery disease. In a subgroup of patients with a normal BMI, this result was preserved. BMI alone did not predict the poor clinical outcomes in this population.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Stratification using LBMI helped to predict adverse events in patients with coronary artery disease who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. It might be more beneficial to use LBMI for stratifying risk in patients with a normal BMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the SHINANO registry investigators: Shoji Hotta, Ina Central Hospital, Ina, Japan; Yuichi Kamiyoshi, Nagano Municipal Hospital, Nagano, Japan; Takuya Maruyama, Shinonoi General Hospital, Nagano, Japan; Noboru Watanabe, Hokushin General Hospital, Nakano, Japan; Takayuki Eisawa, Komoro Kosei General Hospital, Komoro, Japan; Shinichi Aso, Aizawa Hospital, Matsumoto, Japan; Shinichirou Uchikawa, Azumino Red Cross Hospital, Azumino, Japan; Naoto Hashizume, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto, Japan; Noriyuki Sekimura, Matsumoto Medical Centre, Matsumoto, Japan; Takehiro Morita, Nagano Matsushiro General Hospital, Nagano, Japan.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Shoji Hotta, Yuichi Kamiyoshi, Takuya Maruyama, Noboru Watanabe, Takayuki Eisawa, Shinichi Aso, Shinichirou Uchikawa, Naoto Hashizume, Noriyuki Sekimura and Takehiro Morita.

Contributors: HKo, MK, HN, HKi, EM, HA and TS participated in the acquisition of the data at each participating hospital. HH, TM, SE and YM were responsible for the conception and design of the study. HM and UI drafted the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of each participating hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Shoji Hotta, Yuichi Kamiyoshi, Takuya Maruyama, Noboru Watanabe, Takayuki Eisawa, Shinichi Aso, Shinichirou Uchikawa, Naoto Hashizume, Noriyuki Sekimura, and Takehiro Morita

References

- 1.Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB et al. . Overweight, obesity, mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med 2006;355:763–78. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000;894:i–xii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF et al. . Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 2004;293:1861–7. doi:10.1001/jama.293.15.1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H et al. . Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:71–82. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.113905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolds K et al. . The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic clustering: prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999–2004). Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1617–24. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.15.1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong JS, Port FK, Hulbert-Shearon TE et al. . Survival advantage in Asian American end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int 1999;55:2515–23. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allison DB, Zhu SK, Plankey M et al. . Differential associations of body mass index and adiposity with all-cause mortality among men in the first and second National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES I and NHANES II) follow-up studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:410–16. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miura T, Miyashita Y, Motoki H et al. . In-hospital clinical outcomes of elderly patients (≥80 years) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ J 2014;78:1097–103. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James W. Research on obesity. London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD et al. . Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2007;116:2634–53. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP et al. . An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/America Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:2064–89. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e318296aeca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ueshima H et al. . Diagnostic criteria for dyslipidemia. Executive summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Japan—2012 version. J Atheroscler Thromb 2013;20:517–23. doi:10.5551/jat.15792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang TJ, Levy D, Benjamin EJ et al. . The epidemiology of “asymptomatic” left ventricular systolic dysfunction: implications for screening. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:907–16. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndrepepa G, Fusaro M, Cassese S et al. . Relation of body mass index to bleeding during percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2015;115:434–40. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franzosi MG. Should we continue to use BMI as a cardiovascular risk factor? Lancet 2006;368:624–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69222-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Schutter A, Lavie CJ, Arce K et al. . Correlation and discrepancies between obesity by body mass index and body fat in patients with coronary heart disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2013;33:77–83. doi:10.1097/HCR.0b013e31828254fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen I, Mark AE. Elevated body mass index and mortality risk in the elderly. Obesity 2007;8:41–59. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James DC. Gender differences in body mass index and weight loss strategies among African American. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:1360–2. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(03)01071-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J et al. . Normal weight obesity: a risk factor for cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality. Eur Heart J 2010;31:737–46. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myint PK, Kwok CS, Luben RN et al. . Body fat percentage, body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of mortality and cardiovascular disease. Heart 2014;100:1613–19. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han SS, Kim KW, Kim KI et al. . Lean mass index: a better predictor of mortality than body mass index in elderly Asians. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:312–17. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navaneethan SD, Kirwan JP, Arrigain S et al. . Adiposity measures, lean body mass, physical activity and mortality: NHANES 1999–2004. BMC Nephrol 2014;15:108 doi:10.1186/1471-2369-15-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Patel DA et al. . Body composition and survival in stable coronary heart disease: impact of lean mass index and body fat in the “obesity paradox”. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1374–80. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Artham SM et al. . The obesity paradox, weight loss, and coronary disease. Am J Med 2009;122:1106–14. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heiat A, Vaccarion V, Krumholz HM. An evidence-based assessment of federal guidelines for overweight and obesity as they apply to elderly persons. Arch Intern Med 2011;161:1194–203. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.9.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang BT, Peng Y, Liu W et al. . Lean body index, body fat and survival in Chinese patients with coronary artery disease. QJM Published Online First: 21 Jan 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcv013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero-Corral A, Montori VM, Somers VK et al. . Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort study. Lancet 2006;368:666–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69251-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM et al. . Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. doi:10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Syddall H, Roberts HC, Evandrou M et al. . Prevalence and correlates of frailty among community-dwelling older men and women: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing 2010;39:197–203. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R et al. . Midarm muscle circumference, physical performance and mortality: results form the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE study). Clin Nutr 2010;29:441–7. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]