Abstract

Protein synthesis involves the accurate attachment of amino acids to their matching tRNA molecules. Mistranslating the amino acids serine or glycine for alanine is prevented by the function of independent but collaborative aminoacylation and editing domains of alanyl-tRNA synthetases (AlaRSs). Here we show that the C-Ala domain plays a key role in AlaRS function. The C-Ala domain is universally tethered to the editing domain both in AlaRS and in many homologous free-standing, editing proteins. Crystal structure and functional analyses showed that C-Ala forms an ancient single-stranded nucleic acid binding motif that promotes cooperative binding of both aminoacylation and editing domains to tRNAAla. In addition, C-Ala may have played an essential role in the evolution of AlaRSs by coupling aminoacylation to editing to prevent mistranslation.

The algorithm of the genetic code is established in the first reaction of protein synthesis. In this reaction, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARSs) catalyze the attachment of amino acids to their cognate transfer RNAs (tRNAs) that bear the triplet anticodons of the genetic code. When a tRNA is acylated with the wrong amino acid, mistranslation occurs if the misacylated tRNA is released from the synthetase, captured by elongation factor, and used at the ribosome for peptide synthesis. To prevent mistranslation, some AARSs have separate editing activities that hydrolyze the misacylated amino acid from the tRNA (1–3). Because an editing-defective tRNA synthetase is toxic to bacterial and mammalian cells (4, 5), and is causally linked to disease in animals (6), strong selective pressure retains these editing activities throughout evolution.

A particular challenge appears to be avoiding mistranslation of serine or glycine for alanine. All three kingdoms of life contain free-standing editing-proficient homologs of the editing domains found in AlaRSs (7). These proteins—known as AlaXps—provide functional redundancy by capturing mischarged tRNAAla’s that escape the embedded editing activities of AlaRSs (8). Although free-standing editing domains having counterparts in ThrRS and ProRS (7, 9, 10), they are not as evolutionarily conserved as AlaXps. Moreover, enzymes like LeuRS, IleRS, and ValRS lack any freestanding editing domain counterparts (1, 2, 11, 12). Despite the multiple checkpoints to prevent mischarging of tRNAAla, not known is how the apparatus for preventing confusion of serine and glycine for alanine was assembled. . To pursue this question, we focused on a third domain separate from the editing and aminoacylation domains, known as C-Ala, which is found in all AlaRSs and is tethered to their editing domains.

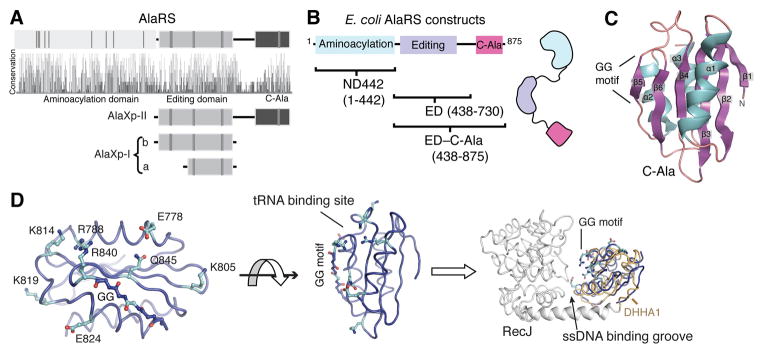

The modular arrangement of domains in AlaRSs is evolutionarily conserved (13) (Fig. 1A). The N-terminal aminoacylation domain is active as an isolated fragment and its three dimensional structure is that of a typical class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. The central editing domain is homologous to the editing domain of the class II ThrRS (14, 15). Lastly, a linker tethers the third (C-Ala) domain to the editing domain. In contrast to the other two domains, C-Ala is only loosely conserved and its structure is unknown. Based on a survey of AlaRS sequences we predicted that a fragment corresponding to residues 766 to 875 of E. coli AlaRS would form a structural unit (Fig. 1B). The corresponding region of Aquifex aeolicus AlaRS is the 110 amino acid fragment encompassing residues 758–867, which was expressed in E. coli, purified and crystallized. The structure was solved to a resolution of 1.85 Å (Table S1), and showed a globular domain having an α/β-fold, comprised of a central six-stranded β-antiparallel sheet flanked by two α-helices on one side and one α-helix on the other (Fig. 1C). Although sequences of C-Ala are highly diverged, structural constraints are seen. The highly conserved Gly838-Gly839 in β5 (Fig. S1A) allows a sharp turn that would be disallowed for non-Gly residues (Fig. 1C, S1B). The following residue (Arg840 in A. aeolicus C-Ala) is fixed by this sharp turn with its sidechain positioned upwards, at the center of the proposed nucleic acid binding interface (see below). This Arg (or Lys) is universally conserved in AlaRSs. Given that strand β5 has to be exposed for binding with tRNA, the bulged GG motif additionally prevents intermolecular edge-to-edge aggregation, which occurs easily between solvent accessible β-strand edges (16). Except for the GG motif, four well conserved residues (Val812, Ala822, Gly848, Ala857) form the hydrophobic core of C-Ala, with other residues only generally conserved in type (Fig. S1A). This conservation is consistent with C-Ala domains in all AlaRSs folding into a similar structure.

Fig. 1. General design of AlaRS and C-Ala structure.

(A) Highly conserved AlaRS domain scheme throughout evolution. Conservation panel shows the relative sequence identity of the 410 aligned AlaRS sequences. Some strictly conserved amino acids in each group are shown as gray vertical bars.

(B) Constructs of E. coli AlaRS used in this paper.

(C) The overall structure of A. aeolicus C-Ala.

(D) The C-terminal half (809–879 region) contains relatively conserved surface residues that face the single strand nucleic acid binding groove when C-Ala (blue) is superimposed onto the DHHA1 domain (yellow) of RecJ (grey).

The distal portion of C-Ala (799–869) is annotated as a DHHA1 domain (as seen in the single strand exonuclease RecJ) in the PFAM bioinformatics database (17). Although this segment is represented in the C-terminal half of our solved C-Ala structure, the structure of the remainder of C-Ala cannot be estimated from the PFAM database. In spite of the lack of high sequence similarity, C-Ala and DHHA1 of RecJ are closely similar structures (rmsd = 2.0 Å over the 97 Cα positions (Fig. S1D)) and are true homologs (Fig. S1B-E). The DHHA1 domain in RecJ binds to ssDNA by forming a central groove with the N-terminal nuclease domain (18). Superimposing C-Ala with the DHHA1 domain of RecJ revealed that the conserved GG of strand β5 in C-Ala is oriented towards this groove, as is the GG motif of the corresponding β-strand of DHHA1 (Fig. 1D). Relatively conserved surface residues (Glu778, Arg781, Lys805, Arg827, Arg840 and Gln845) in C-Ala are all clustered around the side formed by the GG motif (Fig. 1D), and most are restricted to strong hydrogen donors (R/K/Q). Thus, C-Ala most likely uses this side of the GG motif to bind tRNA.

We predicted that C-Ala binds to the elbow of the L-shaped tRNA, formed by the D- and T- loops (Fig. S2). This prediction was confirmed by footprinting tRNAAla, using lead cleavage as a probe. Fragments of AlaRS comprising the editing domain (ED), with and without tethered C-Ala (ED–C-Ala) (Fig. 1B), were compared by the lead-cleavage pattern of tRNAAla, which showed that C-Ala specifically protected the D-loop moiety of the tRNAAla elbow (Fig. 2A). Although mischarged (with Ser or Gly) tRNAAla is deacylated by AlaRS, a similarly mischarged truncated tRNAAla substrate lacking the tRNA elbow cannot be deacylated (19). Thus, C-Ala appears to specifically recognize the L-shape (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. C-Ala targets the elbow of tRNAAla and is the major binding module of AlaRS.

(A) Lead footprinting of 5′-[32P]-tRNAAla. Two sites, U17 and G18 on tRNAAla(UGC) transcript, were cleaved by lead ion, and specifically protected by ED–C-Ala but not by ED.

(B) Model of full-length AlaRS-tRNAAla complex. The detected contacts are shown as spheres on the tRNA model.

(C) Retardation of electrophoretic mobility of 3′-[32P]-tRNAAla by binding of specific fragments of E. coli AlaRS. Shown are full-length AlaRS (●), C-Ala (○), ED–C-Ala (▲), ED (□), ND442 (▼), ND442–ED (■). The equilibrium response at each concentration was fitted to a single-site binding model. Error bars are SD’s from triplicates.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) measured binding of all domains and domain combinations to tRNAAla (Fig. 2C). The affinity of full-length AlaRS was modest (Kd = 3.0 ± 0.3 μM (SEM)), and close to the measured Michaelis constant for tRNA aminoacylation (tRNAAla(UGC), KM = 2.8 μM) (20). Constructs that had either the aminoacylation domain (ND442) or ED alone had lower affinity for tRNAAla, with Kd values of 18 μM and 50 μM, respectively (Fig. 2C). Fusing these two domains together (ND442–ED) gave a Kd that was intermediate to the individual Kd’s (38 μM), suggesting that, when the domains are combined, energetic binding contributions of each are partly cancelled out (presumably a conformational change that costs some energy (21)). Furthermore, C-Ala bound to tRNA with a relatively high affinity (Kd = 0.8 μM), and ED–C-Ala bound tRNAAla with almost the same Kd (2.2 μM) as that of full-length enzyme. Thus, C-Ala is important for binding tRNAAla.

In all AlaRSs, C-Ala is tethered to the editing domain by a linker that is a predicted α-helical coiled-coil. Without C-Ala, editing activity for ED was reduced to ~ 1/1000 of E. coli AlaRS (8). As mentioned above, the linker and C-Ala have high sequence diversity across species. To examine the functional conservation of C-Ala in AlaRS, we fused C-Ala from A. aeolicus to ED of E. coli AlaRS. The editing activity was boosted from about 0.1% to about 10% of native AlaRS. Including the linker in the swap further boosted the activity to about 20% of the E. coli enzyme. Grafting C-Ala and its linker from human AlaRS to ED of E. coli AlaRS gave nearly full activity for clearance of Ser-tRNAAla (Fig. 3). Thus, a conserved function for C-Ala and the linker that tethers it to ED is likely.

Fig. 3. The C-terminal region is functionally conserved.

Top: Four different domain-swapped AlaRS constructs. Bottom: Deacylation of Ser-tRNAAla. Shown are E. coli ED–C-Ala (■), E. coli AlaRS438-698-H. sapiens AlaRS756-968 (●), E. coli AlaRS438-698-A. aeolicus AlaRS694-867 (▽), E. coli AlaRS438-769-A. aeolicus AlaRS764-867 (▲), and no enzyme control (○).

Clearly, the modular arrangement of functional domains along the sequences of AlaRSs (Fig. 1A) might have arisen from fusions of genes encoding separable domains. Selective pressure for fusion would come from advantages of having domains cooperate beneficially. To investigate this question, we split E. coli AlaRS into halves—ND442 and ED–C-Ala (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the two domains functioning independently (8, 22), we could detect no interaction between them using two different assays. To investigate whether the two domains could assemble onto one tRNA, gel shift assays were performed with 3′-end radiolabeled E. coli tRNAAla, in the presence of ND442 or of ED–C-Ala, or both. We first established a concentration of ED–C-Ala that allowed formation of a stable binary complex with tRNAAla. Next, we added an amount of ND442 that was insufficient to form a complex with tRNAAla by itself. Under these conditions, a ternary complex was formed, with the amount of ternary complex increasing with the concentration of ND442 (Fig. 4B). Thus, ternary complex formation is cooperative, that is, binding of ND442 is promoted by the presence of ED–C-Ala.

Fig. 4. C-Ala brings together the editing center and aminoacylation domain on tRNAAla.

(A) Schematic diagrams are shown with E. coli AlaRS broken into halves, and used for characterizing the possible cooperativity in the experiments below.

(B) C-Ala dependent ternary complex formation. PAGE of mixtures containing 0.1 μM 3′-[32P]-tRNAAla, 3.0 μM ED–C-Ala or ED and increasing amounts of fragment ND442.

(C) Specific enhancement of ND442 aminoacylation activity by ED–C-Ala, but not by ED. Error bars are SD’s from triplicates.

A parallel experiment showed that deletion of C-Ala from ED–C-Ala severely reduced binding of ED to tRNAAla and thus also eliminated formation of the ternary complex (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these data show that tRNAAla serves as a bridge to cooperatively bring together editing and aminoacylation centers, and that the ability of tRNAAla to play this role is C-Ala-dependent. To further validate these conclusions, we checked whether C-Ala-dependent ternary complex formation could facilitate the activity of the aminoacylation domain. A series of concentrations of ED–C-Ala (3–80 μM) were incubated together with ND442 in the aminoacylation assay (Fig. 4C). Dramatic enhancement of ND442 aminoacylation activity was induced upon addition of ED–C-Ala, with an apparent Kd of 6.1 ± 1.2 μM (this “functional” apparent Kd is comparable to the estimated Kd of 2.2 ± 0.5 μM from EMSA analysis, Fig. 2C). Adding BSA (10 μM) to the system slightly decreased the apparent activity in all assays, with no change to the effect of ED–C-Ala on the activity of ND442 (Fig. S4A). Although ED is able to bind weakly to tRNAAla (Kd = 50 μM), when high concentrations (80 μM) of ED were added, no enhancement of ND442 aminoacylation activity was seen (Fig. 4C, S4C). Thus, C-Ala brings together aminoacylation and editing domains to bind simultaneously to the acceptor stem (Fig. 4D). Without C-Ala, the binding of tRNA to ND442 and ED is not able to make editing collaborative with aminoacylation.

A docking model positions the aminoacylation and editing domains on opposite sides of the tRNA acceptor stem, where they each make contact with the G3•U70 base pair—using both the major and minor grooves of tRNAAla (Fig. 2B, S2). Earlier experiments showed that both aminoacylation and editing were sensitive to the same G•U pair (8, 23, 24), and it is now clear that C-Ala provides the architecture for bringing together the two domains on the same RNA helix. In this way, the editing domain checks for mischarging by picking out tRNAs that have Gly or Ser and a G3•U70 pair. Because G3•U70 is specific to tRNAAla’s and thus marks a tRNA as specific for alanine, the editing domain (before being coupled to the aminoacylation domain) could easily pick out in trans those tRNAAla’s that are mischarged with Gly or Ser and avoid clearing Gly or Ser from their cognate tRNAs (tRNAGly and tRNASer, respectively). C-Ala is distinct from any other tRNA binding domain, including the EMAPII/Trbp111 domain (25), C-domain of LeuRS (26, 27), and N-domain of human LysRS (28), which also bind to the elbow region of tRNAs. Additionally, these domains are not linked to both a synthetase and a free-standing editing domain and are not known to promote collaboration between editing and aminoacylation functions.

Three types (Ia, Ib, II) of free-standing genome-encoded AlaXps are widely distributed in all three kingdoms of life and act in trans to clear tRNAAla mischarged with Ser or Gly (7, 8, 29, 30). Type Ia AlaXp lacks the Gly-rich motif near the N-terminus of the editing motif of type Ib and type II AlaXps (31). However, unlike types Ia and Ib AlaXps that are comprised of just the editing domain, type II AlaXp has the C-Ala domain (Fig. 1A). A highly resolved phylogenetic tree shows the expected canonical patterns of ThrRS and AlaRS, where the bacterial versions are specifically related to, but deeply separated from, eukaryotic lineages (Fig. S5) (32). This phylogenetic analysis implies that all three forms of AlaXp evolved in the ancestral community. This phylogeny also suggests that AlaXp-II is derived from AlaXp-I. The editing domain of ThrRS is closest to AlaXp-I, thus suggesting an early separation that split the original editing enzyme into two different specificities, one for tRNAThr and the other for tRNAAla. Most importantly, the phylogenetic analysis indicates that the editing domain of AlaRS appeared concurrently with the ancient, most-developed and largest free-standing editing enzyme, the C-Ala-containing AlaXp-II. Thus, C-Ala may have been instrumental in bringing together editing and aminoacylation domains on one tRNA to ultimately (through fusion) create AlaRS (Fig. S6).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant GM 15539 from the National Institutes of Health and by a fellowship from the National Foundation for Cancer Research. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID:3G98).

References and Notes

- 1.Nureki O, et al. Science. 1998;280:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukai S, et al. Cell. 2000;103:793–803. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dock-Bregeon A, et al. Cell. 2000;103:877–884. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Döring V, et al. Science. 2001;292:501–504. doi: 10.1126/science.1057718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nangle LA, Motta CM, Schimmel P. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JW, et al. Nature. 2006;443:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahel I, Korencic D, Ibba M, Söll D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15422–15427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136934100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beebe K, Mock M, Merriman E, Schimmel P. Nature. 2008;451:90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature06454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong FC, Beuning PJ, Silvers C, Musier-Forsyth K. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52857–52864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korencic D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10260–10265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403926101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvian LF, Wang J, Steitz TA. Science. 1999;285:1074–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:915–922. doi: 10.1038/nsmb985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribas De Pouplana L, Musier-Forsyth K, Schimmel P. In: The Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Ibba M, Francklyn C, Cusack S, editors. Eurekah; Georgetown: 2005. pp. 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankaranarayanan R, et al. Cell. 1999;97:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beebe K, Ribas De Pouplana L, Schimmel P. EMBO J. 2003;22:668–675. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finn R, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamagata A, Kakuta Y, Masui R, Fukuyama K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5908–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092547099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beebe K, Merriman E, Schimmel P. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45056–45061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou YM, Schimmel P. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4942–4947. doi: 10.1021/bi00438a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gale AJ, Shi JP, Schimmel P. Biochemistry. 1996;35:608–615. doi: 10.1021/bi9520904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasin M, Regan L, Schimmel P. Nature. 1983;306:441–447. doi: 10.1038/306441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buechter DD, Schimmel P. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5267–5272. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swairjo MA, et al. Mol Cell. 2004;13:829–841. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomanbhoy T, et al. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:344–348. doi: 10.1038/86228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4985–4996. doi: 10.1021/bi6024935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu JL, Martinis SA. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francin M, Kaminska M, Kerjan P, Mirande M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1762–1769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sokabe M, Okada A, Yao M, Nakashima T, Tanaka I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11669–11674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502119102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chong YE, Yang XL, Schimmel P. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30073–30078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805943200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63:390–400. doi: 10.1107/S090744490605640X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woese CR, Olsen GJ, Ibba M, Söll D. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:202–236. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.202-236.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.