Abstract

Hedgehog (Hh) morphogen signalling plays an essential role in tissue development and homeostasis. While much is known about the Hh signal transduction pathway, far less is known about the molecules that regulate the expression of the hedgehog (hh) ligand itself. Here we reveal that Shaggy (Sgg), the Drosophila melanogaster orthologue of GSK3β, and the N-end Rule Ubiquitin-protein ligase Hyperplastic Discs (Hyd) act together to co-ordinate Hedgehog signalling through regulating hh ligand expression and Cubitus interruptus (Ci) expression. Increased hh and Ci expression within hyd mutant clones was effectively suppressed by sgg RNAi, placing sgg downstream of hyd. Functionally, sgg RNAi also rescued the adult hyd mutant head phenotype. Consistent with the genetic interactions, we found Hyd to physically interact with Sgg and Ci. Taken together we propose that Hyd and Sgg function to co-ordinate hh ligand and Ci expression, which in turn influences important developmental signalling pathways during imaginal disc development. These findings are important as tight temporal/spatial regulation of hh ligand expression underlies its important roles in animal development and tissue homeostasis. When deregulated, hh ligand family misexpression underlies numerous human diseases (e.g., colorectal, lung, pancreatic and haematological cancers) and developmental defects (e.g., cyclopia and polydactyly). In summary, our Drosophila-based findings highlight an apical role for Hyd and Sgg in initiating Hedgehog signalling, which could also be evolutionarily conserved in mammals.

Introduction

Hh morphogens act in multicellular animals to control development and homeostasis of adult tissues and organs [1, 2]. In Drosophila, the Hh pathway (HhP) governs many aspects of Drosophila development that includes adult eye and head development from the larval eye-antennal imaginal disc (EA disc)[3]. In an unstimulated cell, the unbound Hh-receptor Patched (Ptc) constitutively represses Hh signalling by indirectly suppressing the pathway’s transcriptional effector Cubitus Interruptus (Ci). Whereupon Hh ligand stimulation, Ci activity is de-repressed to permit of expression of Ci’s target genes[2].

The phosphorylation-directed threonine/serine kinase Sgg plays as important role in suppressing Ci activity, as well as being implicated in a diverse array of signal transduction pathways that include insulin, stress, growth factor, cytokine and morphogen signalling[4]. Within the HhP, Sgg, together with Protein kinase A and Casein Kinase I[5, 6], phosphorylate Ci to create a binding site for the F-box protein Slimb (Slmb, the Drosophila homologue of mammalian βTrCP)[7]. This phosphodependent interaction allows the Slmb-bearing Cullin-1 E3 complex (Cul1Slmb) to promote Ci ubiquitylation and its subsequent partial proteolysis. Removal of Ci’s C-terminal transcriptional transactivation domain converts full-length 155kDa Ci (Ci155) into a 75kDa Ci (Ci75) transcriptional repressor. As part of a negative feedback mechanism, an alternative Cullin-3 based complex (Cul3Rdx) also targets Ci155 for ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation using the substrate specificity factor, Roadkill (Rdx), the Drosophila homologue of Speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP)[8, 9].

Although much is known about the molecular mechanisms governing Ci155 expression in the Hh-stimulated cell, far less is know about the upstream events that govern the expression of the hedgehog ligand. Hyperplastic Discs (Hyd), a ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3) of the N-end rule pathway[10] represents one of the few non-transcription factors identified as a suppressor of hh ligand expression. Hyd was originally identified as a regulator of imaginal disc development, with hyd mutant alleles resulting in either hyperplastic or hypoplastic discs[11]. Hyd contains a number of domains related to ubiquitin signalling, which include a ubiquitin binding domain[12], a substrate recruitment domain for N-end rule substrates[13] and a catalytic HECT domain[14]—the presence of which defines Hyd as an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase. While little is known about Hyd’s molecular functions outside of the HhP, its mammalian orthologues are implicated in DNA damage signalling[15–17], miRNA activity[18], metabolism[19] and cell cycle checkpoint control [20–23].

Previous work by Lee et al[24] revealed that hyd mutant (hyd K3.5) clone-bearing EA discs were hyperplastic, spatially misexpressed hh and exhibited increased Ci155 levels within clones[24]. Deletion of hh function within the hyd K3.5 mutant clones partially rescued the EA disc overgrowth phenotype, but did not rescue the increased levels of Ci155 expression. Therefore suggesting that Hyd can normally suppresses Ci155 expression independent of any effect mediated by hh ligand overexpression. These results indicated that Hyd may have independent roles in controlling the (i) initiation of Hh signalling by regulating hh ligand expression and (ii) modulating the pathway response by governing Ci155 expression. What remained unclear from this elegant work was the underlying molecular mechanism by which Hyd might independently regulate hh and Ci155 expression?

Here we identify a genetic interaction between hyd and sgg in the regulating HhP activity in the developing EA disc. Our work reveals a previously unreported role for Sgg in regulating hh ligand expression, while identification of a physical interaction between Hyd, Sgg and Ci155 provides a potential mechanism by which Hyd could influence both hh ligand and Ci155 expression patterns. Overall, these findings provide new mechanistic insights into how Hyd and Sgg influence different aspects of Hh signalling.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

Constructs were made by standard PCR-based cloning methods using restriction enzyme cloning. hyd and EDD inserts were ligated into a modified pMT or pcDNA5 vector (Invitrogen) containing an N-terminal HA-Strep tag. hyd mutant constructs were constructed using standard site-directed mutagenesis using primers targeting: UBRmt (C1272A+ C1274A), PABCmt (Y2509A+C2527A) and HECTmt (C2854A) domains. Inserts for sgg were cloned into a C-terminal V5/FLAG-tagged pMT or pcDNA5 vector. Myc-GLI2 expression vector was kindly provided by Rune Toftgard (Karolinska Institute, Sweden). Drosophila cDNAs were acquired from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Centre, DGRC. UAS-hyd WT and hyd C>A (HECTmt C2854A) inserts (NotI-NotI) were cloned into pUAST and sent to Bestgene Inc., USA for transgenic production.

Genomic DNA sequencing

hyd alleles were sequenced by Sanger sequencing using an array of overlapping primers. Sequences were aligned against hyd genomic DNA using SerialCloner software.

5’ FL hyd ATG: GTTTCCATGCAATTTGTTTTGCAACC

5' hyd genomic @2580: CGAAAGAAGCTTGCAGAAGTCCATGC

5' hyd genomic @3104: CTTGACTTGACCAAATCAGACGC

5' hyd genomic @3627: CGTGCCCGAAGACCTTATCTCCCTGCTGG

5' hyd genomic @4156: GGATATCTGAAGAATTGCAGC

5' hyd genomic @4680: CGCCGCTTCTTGTGGGACAAATTCCGG

5' hyd genomic @5211: GTGAAGGACGTGGTGTTTGTCG

5' hyd genomic @5736: GTGCTTCGTGATGGCAATGGAGC

5' hyd genomic @6255: GCAACTATGAGTTCATCCGCTGCCGG

5' hyd genomic @6779: GCTAAAGGAGGCCATGATTTTCCCG

5' hyd genomic @7302: GATAATGATATGCCGGACCATGATCTGGAGC

3’seq hyd@4536: AACACAGCTCTGCACGTATTTGTTGC

5'hyd@3000: CTCGACAAGCGCTTACGTTAG

5' hyd genomic @6779: GCTAAAGGAGGCCATGATTTTCCCG

5' hyd genomic @7302: GATAATGATATGCCGGACCATGATCTGGAGC

5' hyd genomic @7775: GCTGCACAAGATATCCATCGAGG

5' hyd genomic @8309: GGACGGCATGCAAGATGACGAGAGC

5' hyd genomic @8839: CGACAACGGCCAGCAACTTGGC

5' hyd genomic @9384: GCTCACACACCTCTGAGCACCGAGACG

5' hyd genomic @9955: CGATTCTAGTAAGACGGGTGATGG

5' hyd genomic @10505: GCCGCTGGAAGCTAACTCTGG

5' hyd genomic @11029: CGTTCGGCCCGTGAGAGGAAGG

5' hyd genomic @11570: GCCAAGGCTTTGCATCATTCGAGCG

5' hyd genomic @12088: GGAGGTATGGGCAAATATTGCG

5' hyd genomic @12548: CGACTGCGAATACTTGTATCTCTCGG

3’ Hyd 3'UTR: TGGCCGTTTTATTGGTTACAATGG

Cell culture

Insect S2 and Cl8 cells were acquired from, and cultured according to, the Drosophila RNAi Screening Centre (DRSC, USA). Transfections were performed using Effectene (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and protein expression induced with 0.35 mM CuSO4. HEK293 (CRL-1573) cells were cultures according to ATCC guidelines and transfected using CaCl2 (Life Technologies).

Pull-down assays, co-IP and Western blotting

Cells were processed for immunoprecipitation (IP) and/or SDS-PAGE/Western blotting as previously described in[25]. Briefly, cells were lysed 48h post-transfection Triton lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 100mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1X Roche protease inhibitor mix, 1X Roche phosphatase inhibitor mix). Post clarification, HA-Strep Hyd was pulled down using either Streptactin sepharose (GE Healthcare) or HA-agarose (clone HA-7) (Sigma) for 1hr at 4°C with rotation. After washing, protein complexes were eluted with one bead volume of 1X NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) and 100mM DTT. To IP endogenous Hyd, 5μl M19 antibody (Santa Cruz) was added to the lysate and incubated at 4°C with rotation for 2 h, followed by Protein-A agarose (Sigma) for 30 min with rotation. Samples were run on BIS-TRIS-gradient gels (Invitrogen) and blotted onto PVDF (Millipore). Antibodies used were: mouse HA (1:2,000 Covance), FLAG M2 (1:2,000 Sigma), SGG GSK-4G-AS (1:5,000 Euromedex), Myc 9B11 (1:6,000 Cell Signalling), V5 (1:2000 AbD Serotec); goat EDD M19 (1:1,000; Santa Cruz); rat Ci 2A1 (1:10 DSHB); mouse, goat and rat HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used 1:5,000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Fly stocks

Alleles used are described in Flybase except the UAS-hyd lines that are described here for the first time. hyd K7.19 and hyd K3.5 were obtained from Jessica Treisman (NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA) while the others were either created using pUAST-mediated transgenesis or purchased from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre. Sp//SM6-TM6 was obtained from Marcos Vidal (Beatson Institute for Cancer Research, Glasgow, UK). Flies were maintained on standard medium at 25°C.

The following lines were created and used for mitotic clone analysis:

yw ey-flp3.6; act>y+>GAL4, UAS-GFP; FRT82B, tubGAL80//SM6-TM6

FRT82B, hh-lacZ/TM6B Tb

FRT82B, hydK7.19 hh-lacZ/TM6B Tb

UAS-sggS9A; FRT82B, hydK7.19 hh-lacZ//SM6-TM6 Tb

UAS-sggS9A; FRT82B, hh-lacZ//SM6-TM6 Tb

UA-sgg-RNAi; FRT82B, hydK7.19 hh-lacZ//SM6-TM6 Tb

UAS-sgg-RNAi; FRT82B, hh-lacZ//SM6-TM6 Tb

UAS-hydWT or-hydC>A; FRT82B,/TM6B Tb

UAS-hydWT or-hydC>A; FRT82B, hydK7.19 /TM6B Tb

The following lines were created and used for wing analysis:

Vg-GAL4

Vg-GAL4; UAS SggS9A / +

Vg-GAL4; UAS SggS9A / UAS hydWT

Vg-GAL4; UAS SggS9A / UAS hydC>A

Vg-GAL4; UAS SggRNAi / +

Vg-GAL4; UAS SggRNAi / UAS hydWT

Vg-GAL4; UAS SggRNAi / UAS hydC>A

Fly Crosses and Clone Production

Eye disc

Using a MARCM-based approach[26] GFP-labelled mitotic clones were generated using ey-flp to recombine FRT82B sites and remove a STOP cassette preventing expression of act-GAL4 to drive UAS-response elements (UAS-GFP and-cDNAs and-RNAi). Use of FRT82B tub-GAL80 ensured expression of UAS-response elements were tightly regulated. For hh expression studies hh-lacZ P30[27] was recombined onto FRT82B and FRT82B hyd k7.19. Three-hour embryo collection windows were used to synchronise L3 collection for dissection of imaginal eye discs.

Wing disc

UAS-sgg and hyd overexpression in the wing disc was mediated by vg-GAL4 or sca-GAL4 expression. Adult wings were imaged 16hrs after emerging from pupae.

Immunofluorescence

L3 eye-antennal discs were dissected in PBS as previously described[28]. Discs were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by washing and mounting in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). All antibodies were diluted in blocking solution. Primary antibodies used were mouse β-Gal (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB), Ptc (1:10; DSHB); rabbit Hh (1:400)[29]; rat Ci 2A1 (1:10; DSHB). Secondary antibodies were mouse, rabbit and rat conjugated to Alexa 594 and Cy5 (1:500; Invitrogen).

Image acquisition and data analysis

Confocal images were captured on a NikonA1R confocal microscope at 20X or 60X magnification. Widefield image sections were captured at 20X on a Zeiss Axioplan II and images deconvolved using Volocity (PerkinElmer). For quantitative analysis, imaged were taken using the same acquisition parameters. Brightfield colour images of heads, wings and notum were acquired using an Olympus SX9 stereomicroscope (4X) attached to a Nikon D300 camera. Image J was used to create a black overlay mask by thresholding the GFP channel images. The subsequent black mask corresponding to GFP negative regions was then superimposed over the Ci155 or βGal images. ImageJ was also used for measuring adult heads, band densitometry and pixel intensity. Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism were used for graphs and ANOVA and t-test statistical analysis.

Results

Hyd binds Ci155 and the Drosophila GSK3β homologue Shaggy

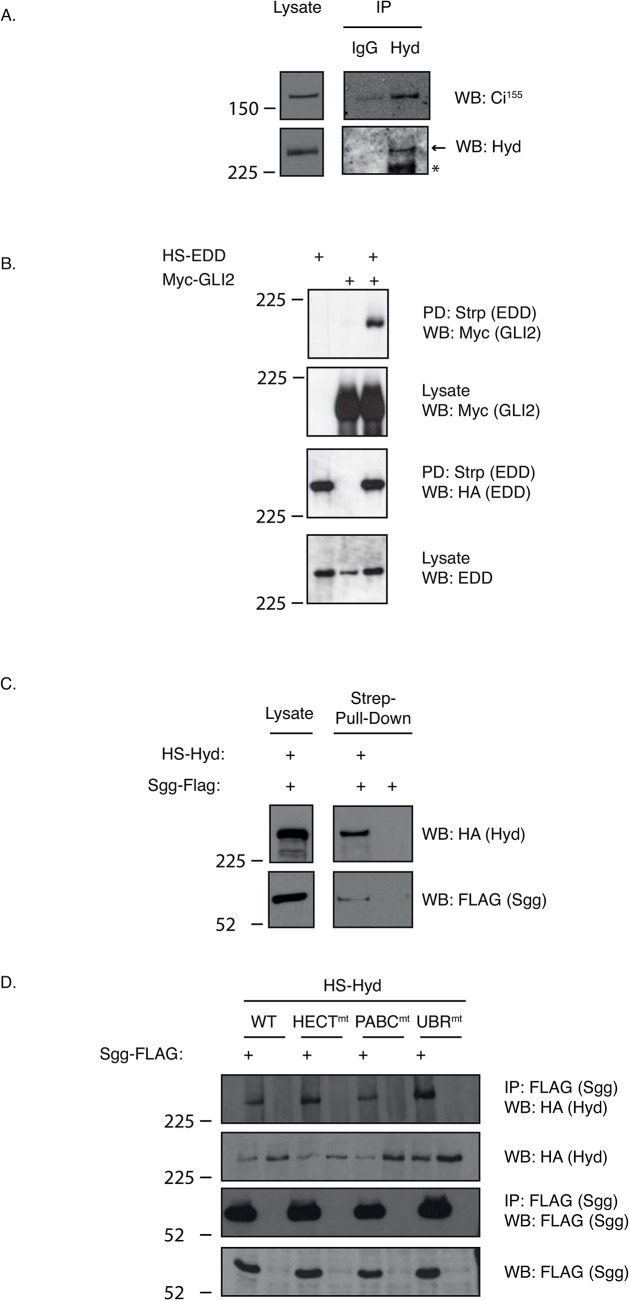

We initially sought to gain a molecular insight into how Hyd might directly regulate Ci155 expression by addressing whether Hyd could physically interact with Ci155. Drosophila wing-disc-derived CL8 cells that express both Hyd and Ci155 were used to investigate endogenous protein interactions. Co-immunoprecipitations (Co-IPs) revealed that Hyd consistently co-purified endogenous Ci155 at levels significantly increased over IgG control levels (Fig 1A). To support these observations we addressed whether Hyd’s human homologue, EDD, could also bind one of the human Ci homologues, GLI2. Exogenously expressed Haemagglutinin-Streptavidin-(HS)-EDD efficiently co-purified full-length Myc-tagged GLI2 from transfected HEK293 cells (Fig 1B). In summary, our data indicated that both Hyd and EDD bind to the HhP's major transcriptional effectors.

Fig 1. Hyd binds the Hedgehog pathway’s key transcriptional effector Ci155 and the Ci-regulatory kinase Sgg.

Co-immunoprecipitation (A,D) and affinity-purification (B,C) studies with the indicated affinity reagents were examined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (A) Drosophila CL8 cells were lysed and incubated with either Hyd or control IgG antibodies and affinity purified by Protein G beads. An arrow indicates the position of the expected size band and an asterisk indicates the presence of an uncharacterised faster migrating Hyd species. (B) Mammalian HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and lysates underwent Streptactin-mediated purification (Strp) to purify Haemagglutinin-Streptactin-EDD (HS-EDD) and detect co-purified Myc-GLI2. (C) Drosophila S2 cells were transfected with either HS-hyd or HS-vector control, lysed and then incubated with Streptactin-affinity resin. Control and Hyd-coated beads were then incubated with Sgg-FLAG expressing S2 lysate and, following washing, analysed for bound Sgg-FLAG. Only the HS-Hyd beads purified FLAG-Sgg. (D) Drosophila S2 cells were co-transfected with the indicated hyd mutant and sgg-FLAG constructs and FLAG-affinity purified complexes were analysed with the indicated antibodies.

A recent report revealed EDD’s interaction with GSK3β[30], a known GLI2 binding protein[5, 6]. This observation provided a potential means of Hyd to indirectly interacting with Ci and prompted us to examine if Hyd could also co-purify GSK3β’s Drosophila homologue, Shaggy (Sgg) (Fig 1C and 1D). HS-Hyd was first purified from HS-hyd transfected S2 cells using Streptactin-affinity resin. Control or HS-Hyd-loaded beads were then incubated with Sgg-FLAG expressing S2 cells lysate. HS-Hyd bound resin, but not control resin, co-purified Sgg-FLAG (Fig 1C). To identify which domains might be important for mediating/promoting the interaction with Sgg, we created a series Hyd constructs with predicted loss-of-function point mutations: HECT(C2854A)[14] to potentially improve the interaction by preventing HECT-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation; and PABC(Y2509A+C2527A)[31] and UBR(C1272A + C1274A)[13] domains to unfold these protein-protein interaction domains. None of the mutants altered the amount of co-purified FLAG-Sgg (Fig 1D), suggesting that other domains/residues are important for Hyd’s interaction with Sgg. Taken together this evidence reveals an evolutionarily conserved ability of Hyd and EDD to bind both the HhP’s key transcriptional effector (Ci/GLI2) as well as one of its key regulatory kinases (Sgg/GSK3β).

The hyd K7.19 allele lacks E3 function and promotes adult head defects

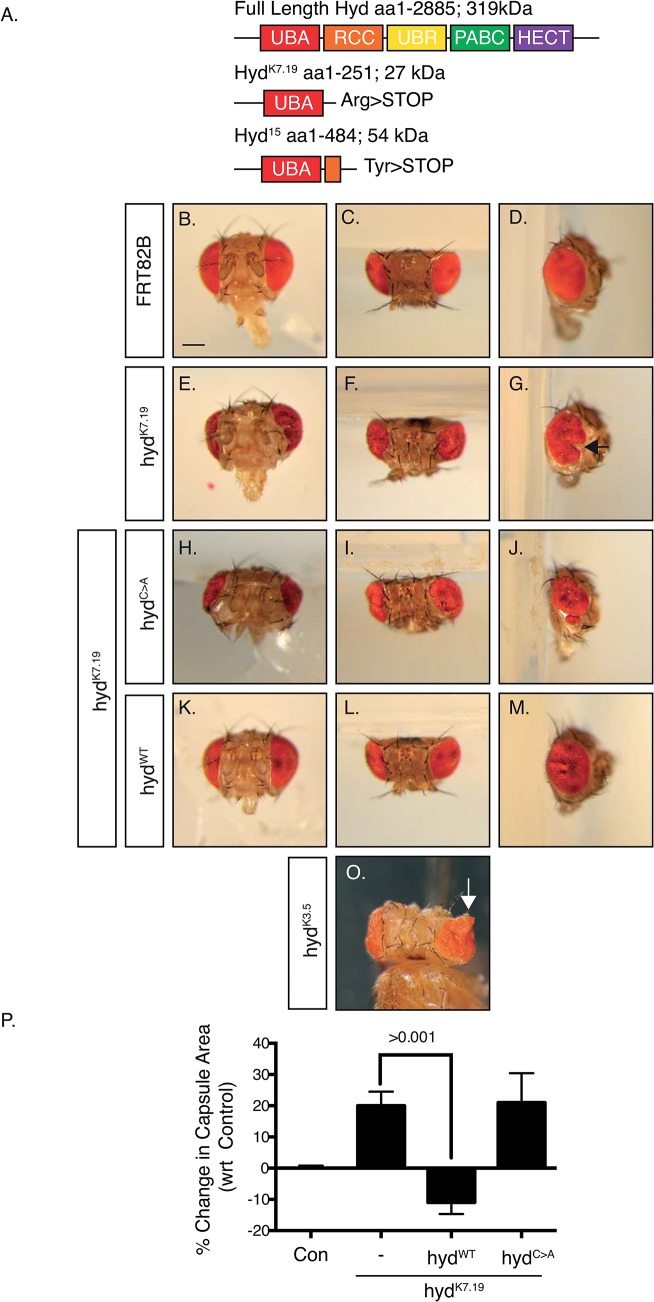

Due to Sgg’s physical interaction with Hyd we wished to determine if perturbed Sgg function would alter the hyd mutant phenotype. As distinct hyd alleles mediate dramatically different effects on imaginal discs[11], we wished to first molecularly characterise a selection of hyd loss of function mutant alleles. Four available hyd alleles (hyd 15, hyd K3.5, hyd K7.19 and hyd wc461) were sequenced to identify nucleotide changes. Analysis revealed nonsense mutations in hyd K7.19 (aaR251>STOP) and hyd 15 (aa485W>STOP) (Fig 2A), but failed to find exon- or intron-associated mutations in hyd K3.5 or hyd wc461. The lack of exon/intron-associated mutations in hyd K3.5 and hyd wc461 suggested these harboured mutations in regulatory regions governing hyd mRNA expression, stability or translation. We chose to carry out all our studies using the most severe truncating mutation hyd K7.19 that, if expressed, would lack all domains apart from the Hyd’s N-terminal UBA domain. Such a protein would therefore lack its ability to bind N-end rule substrates (via it UBR domain)[13], influence miRNA function (via its PABC domain)[18] and function as an E3 enzyme (via its HECT domain)[14] (Fig 2A).

Fig 2. hyd K7.19 is defective in HECT E3 function and causes abnormal head development.

(A) Schematic representation of the full length Hyd protein containing the Ubiquitin Association Domain (UBA), Regulator of Chromatin Condensation-like (RCC), Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase E3 Component N-Recognin (UBR) domain, Poly(A)-Binding Protein C-Terminal (PABC) and Homologous to the E6AP Carboxyl Terminus (HECT) domains and the potential protein products encoded by hyd k7.19 and hyd 15. In comparison to control heads (B-D), hyd k7.19 flies (E-G) exhibited disruption of the adult eye and increased head-capsule area. Co-expression of the hyd WT (K-M), but not hyd C>A (H-J), transgene suppressed the hyd k7.19 phenotype. Scale bar = 200μm. (O) hyd K3.5 flies exhibit eye tissue outgrowths that are not present in hyd k7.19 heads. (P) Quantification of the head capsule area of the indicated genotype. % values are normalised to control. n = >10 of each genotype. s.e.m and indicated p value determined by Student’s t-test.

To generate hyd K7.19 clones throughout the developing EA disc we utilized mitotic recombination—a technique that permits creation of homozygous mutant cells from heterozygous tissue. The MARCM-based system[26] was used with an eyeless promoter driven Flippase (FLP) in combination with a FLP Recombination Target (FRT) marked hyd K7.19 -bearing chromosome (FRT82B hyd K7.19, herein referred to as simply hydK7.19). This then allowed us to create homozygous hyd K7.19 mutant clones specifically within the developing EA disc. Homozygous mitotic clones were also positively marked by GFP expression through FLP-mediated removal of an FRT-STOP-FRT signal upstream of UAS-GFP transgene. The presence of tub-GAL80 on the FRT82B chromosome also ensured that GAL4-mediated transcription only occurred in FRT82B hyd k7.19 homozygous cells.

Animals bearing hyd K7.19 clones in the EA discs were viable, but exhibited dramatic changes in the shape and size of the adult eye together with a significant expansion of the head capsule (Fig 2, compare FRT82B control B-D with E-G). Over 90% of all hyd k7.19 flies showed a ‘puckered’ eye phenotype, reflecting ingress of head capsule at the expense of the eye field along the dorsal-ventral (DV) midline (Fig 2G, arrow). Interestingly, while hyd k3.5 adult heads showed the same eye and heads defects they also exhibited outgrowths from the eye (Fig 2O, arrow)[24] that were never observed in hyd K7.19 heads. Such phenotypic variations potentially reflected the distinct molecular defects associated with the different alleles—an effect commonly observed across allelic series.

To confirm that the hyd K7.19 phenotype was solely due to perturbed hyd function we attempted to rescue the mutant phenotype through expression of wild-type hyd transgene. Expression of a wild type UAS-hyd (hyd WT) (Fig 2H–2J), but not an E3-catalytic dead hyd mutant (hyd C>A) (Fig 2K–2M), transgene rescued the hyd K7.19 phenotype. Quantification of the area of head capsule revealed a significant reduction in hyd K7.19 flies expressing the hyd WT, but not hyd C>A, transgenes (Fig 2P). These results indicated that the gene mutation(s) associated with the hyd K7.19 allele were effectively suppressed by the hyd wt, but not the hyd C>A, transgene. Therefore, it is most likely that the hyd k7.19 phenotype is associated with loss of Hyd’s E3 catalytic activity.

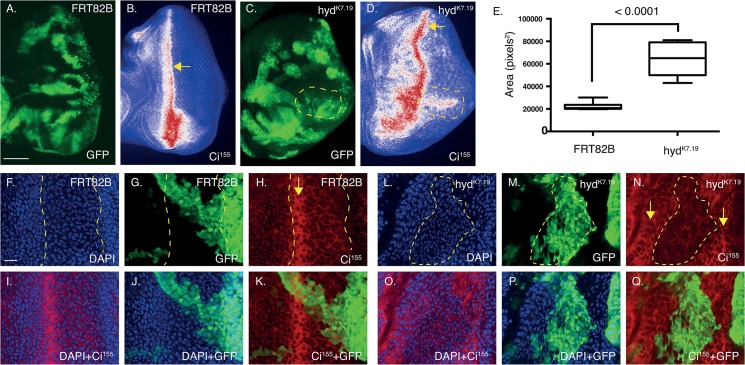

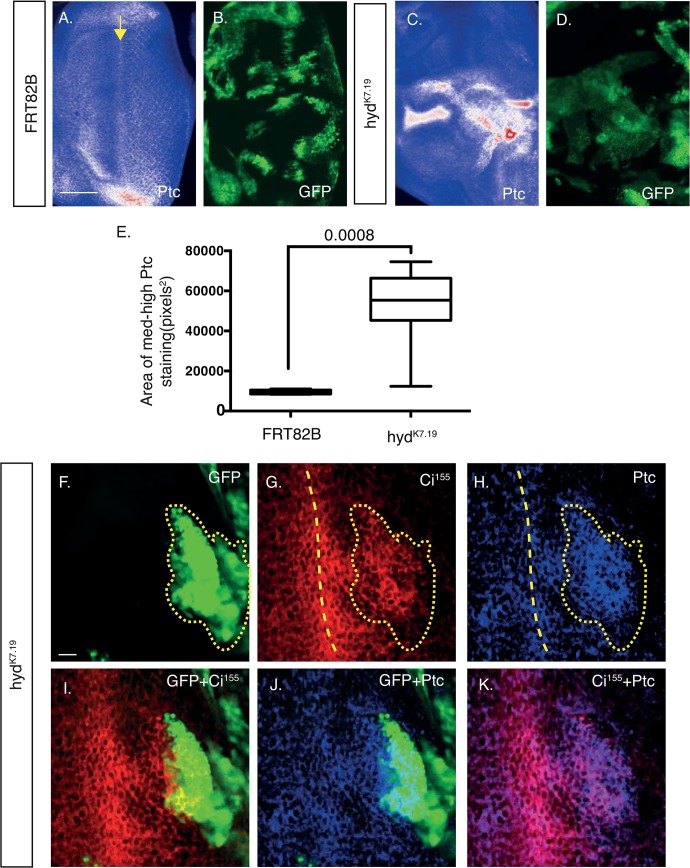

Loss of hyd function increases Ci155 and Ptc expression

Once we had characterised and validated the hyd k7.19 allele we then wished to investigate Ci155 expression patterns. Based on Hyd’s physical interaction with Sgg and Ci155 we predicted that Ci155 expression patterns would be altered. GFP positive mitotic clones in 3rd instar larval EA discs (Fig 3A and 3B panels, respectively) were examined for GFP fluorescence and Ci155 expression by immunofluorescence. Use of an antibody raised against Ci’s C-terminus detected only the active full length Ci155, but not the C-terminally truncated Ci75 transcriptional repressor form[32]. Please note that all images were acquired using fixed illumination/acquisition parameters and Ci155 expression reflected through application of a “Union Jack” lookup table to indicate regions of low (blue), medium (white) and high (red) levels of expression.

Fig 3. hyd K7.19 EA discs exhibit aberrant Ci155 expression patterns and morphogenetic furrow-associated features.

(A-D) Deconvolved widefield and confocal image (F-Q) sections of control FRT82B (A,B, F-K)) and hyd k7.19 (C,D, L-Q) EA discs imaged for direct GFP fluorescence (A,C,G,K), Ci155 immunofluorescence (B,D,H,I,K) and DAPI (A,B,C,E,F,G). (A-D) hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibit abnormal Ci155 expression patterns. A “Union Jack” lookup table was applied to Ci155 images to visualise low (blue), medium (white) and high (red) intensity levels and arrows marks the presumed Ci155 DVS / morphogenetic furrow and an asterisk indicates increased Ci155 staining as a result of the tissue folding over in itself (B). (D) hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibited ectopic Ci155 expression in the posterior compartment (E, marked by a dashed yellow line, which is also overlaid onto C). (E) Quantification of the area of medium-to-high Ci155 signal in control and hyd k7.19 EA discs. n = 5, s.e.m and indicated p value determined by Student’s t-test. (F-Q) hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibit abnormal markers of the morphogenetic furrow. Control FRT82B EA discs exhibited normal nuclei distribution (F) and DVS Ci155 expression (H), while hyd k7.19 discs exhibited irregular patterns (L,N). (F-H) Dashed lines indicated the DVS’s associated high anterior and low posterior Ci155 expression margins (H), which is overlaid onto (F,G). (L-N) A region of low Ci155 expression flanked by two DVS-like regions of high Ci155 expression is marked by a dashed outline (N), which is overlaid onto (L,M). Arrows mark high Ci155 DVS (H), or DVS-like (N), signals. Scales bars (A-D) 50μm and (F-Q) 10μm.

Ci155 expression in the FRT82B control discs showed a characteristic pattern of expression fof high levels in a dorsal-ventral stripe (DVS) that divided the disc into anterior and posterior compartments (Fig 3B, arrow). A small region of high Ci155 staining was also apparent at the posterior/dorsal edge (Fig 3B, arrowhead)[33], while intense signals at the ventral edge coincided with the disc folding over upon itself (Fig 3B asterisk). Please note that Ci155 DVS expression marks the front of the morphogenetic furrow (MF)[34], a morphological feature that, through the action of Hedgehog signalling, progresses in a posterior to anterior direction. Thereby acting to constantly redefine the regions of the EA discs’ anterior and posterior domains[3, 35].

In hyd K7.19 EA discs (Fig 3C and 3D) the general Ci155 DVS staining pattern was perturbed (Fig 3D), exhibiting irregularities in its positioning, width and staining intensity. The presumed DVS (Fig 3D arrow) frequently undulated along the dorsal-ventral axis and exhibited significant broadening, as well as “arcs” of increased Ci155 staining spreading out into the posterior compartment (Fig 3D dashed region). Quantification of the area of medium-to-high Ci155 intensity staining (white+red) revealed >3-fold increase in hyd k7.19 EA discs over control (Fig 3E).

Closer examination of the DVS region of control EA discs revealed well-ordered nuclei showing a characteristic pattern of densely packed nuclei flanking a region of less-dense nuclei (Fig 3F, demarcated by dashed lines). The intense strip of Ci155 expression two-three cells wide (Fig 3H, arrow) marks the anterior boundary between the high and low nuclei densities (Fig 3F). Posterior to the Ci155 DVS, less intense Ci155 staining exhibited a characteristic ‘lattice-like’ staining pattern (Fig 3H) associated with differentiating photoreceptors. In contrast to the regulator patterns seen in the control, hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibited two Ci155 DVS-like signals (Fig 3N, arrows). Potentially indicating the existence of two MFs within the one EA disc—a known effect associated with ectopic hh expression[36]. The DVS region also exhibited disorganised cell nuclei that formed ‘swirls’ (Fig 4A dashed line) that overlapped with Ci155 DVS staining (Fig 4C). Potentially indicating that Ci155-associated MF progression was disrupted.

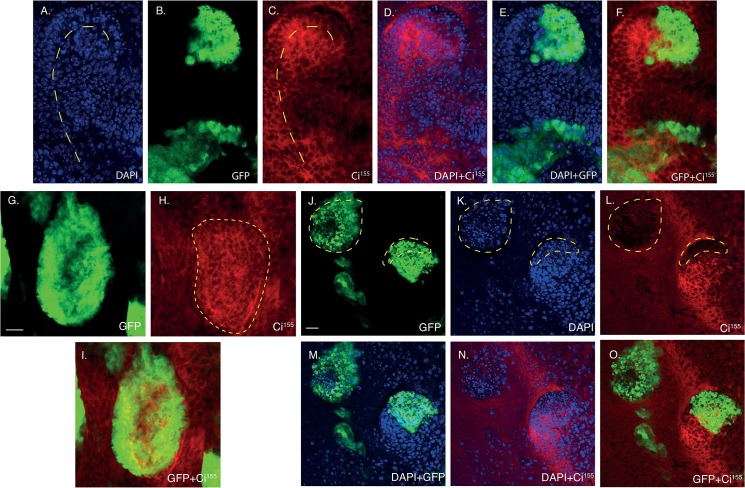

Fig 4. hyd k7.19 clones exhibit distinct patterns of Ci155 expression.

Confocal image sections of hyd k7.19 EA discs imaged for direct GFP fluorescence (B,E,F,G,I,J,M,O) Ci155 immunofluorescence (C,D,F,H,I,L,N,O) and DAPI (A,D,E,K,M,N). (A-F) hyd k7.19 discs exhibited curved arrays of nuclei (A, dashed line) that were reflected in the Ci155 DVS (C, dashed line). (G-I) Posterior hyd k7.19 clones near the DVS exhibited increased Ci155 expression (H, dashed outline). (J-O) Anterior hyd k7.19 clones near the DVS exhibited decreased Ci155 expression (L, low Ci155 marked by dashed lines, which are overlaid onto J,K). Scale bars = 10μm.

Closer assessment of the effects on Ci155 expression within hyd k7.19 clones revealed increased expression within clones located posterior to, and in the vicinity of, the DVS (Fig 4G–4I). Whereas infrequent hyd k7.19 clones well within the anterior compartment exhibited reduced Ci155 expression (Fig 4J–4O, dashed lines). Therefore, in a spatially dependent manner, clonal loss of Hyd function resulted in both cell autonomous increases and decreases in Ci155 expression. Nevertheless, the predominant effect observed in hyd k7.19 EA discs was increased Ci155 expression within and around the DVS, both in and outside of hyd k7.19 clones.

To establish if the increased Ci155 expression patterns translated into increased HhP activity, we next examined the protein product of one of Ci155 target genes, ptc. In control discs (Fig 5A and 5B), the posterior compartment expressed Ptc in a regular lattice-like pattern with a weak dorsal-ventral signal, reminiscent of the Ci155 DVS (Fig 5A, arrow). As with Ci155, hyd K7.19 EA discs exhibited ectopic Ptc staining (white/red signals) that showed no clear, or exclusive, co-localisation with hyd k7.19 GFP clones (compare Fig 5C and 5D). Quantification of the average Ptc signal intensity revealed a marked increase in the Ptc expression levels across the hyd k7.19 EA disc (Fig 5E). Next we used co-immunofluorescence to directly assess whether particular clones located across the EA disc co-localised with altered Ci155 and Ptc expression (Fig 5F–5K). Only hyd K7.19 clones located adjacent and posterior to the DVS demonstrated a clear positive correlation between ectopic Ci155 and Ptc expression (Fig 5G and 5H, respectively). However, when considering the pattern across the rest of the EA disc, neither ectopic expression of Ptc nor Ci155 exclusively co-localised within hyd k7.19 clones (also see Figs 6 and 7). We therefore conclude that the presence of hyd k7.19 clones within an EA disc elicits a generalised increase in HhP activity both within and outside of the clones. Importantly, aberrant Ci155 and Ptc expression patterns in hyd k7.19 EA discs were effectively rescued by co-expression of the UAS-hyd WT transgene (S1 Fig). This effective rescue supported the idea that the aberrant Ci155 expression pattern was specifically caused by the loss of hyd function, rather than any other mutations carried on the hyd k7.19-bearing chromosome arm.

Fig 5. hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibit abnormal Ptc expression.

(A-D) Deconvolved widefield and (F-K) confocal image sections of control FRT82B (A,B) and hyd k7.19 (C,D and F-K) EA discs imaged for GFP fluorescence and the indicated antigens for IF. “Union Jack” lookup table applied to Ptc images (A,C) to visualise low (blue), medium (white) and high (red) intensity levels. (E) Quantification of the area of medium and high Ptc signal. n = 3, s.e.m and indicated p value determined by Student’s t-test. (F-K) Overlapping expression of Ci155 and Ptc immunofluorescence within a hyd k7.19 GFP-positive clone anterior to the Ci155 DVS (F yellow dotted outline, which is overlaid onto G,H). The yellow dashed line indicates the Ci155 DVS, which is overlaid onto H). Scale bars = 50μm (A-D) and 10μm (F-K).

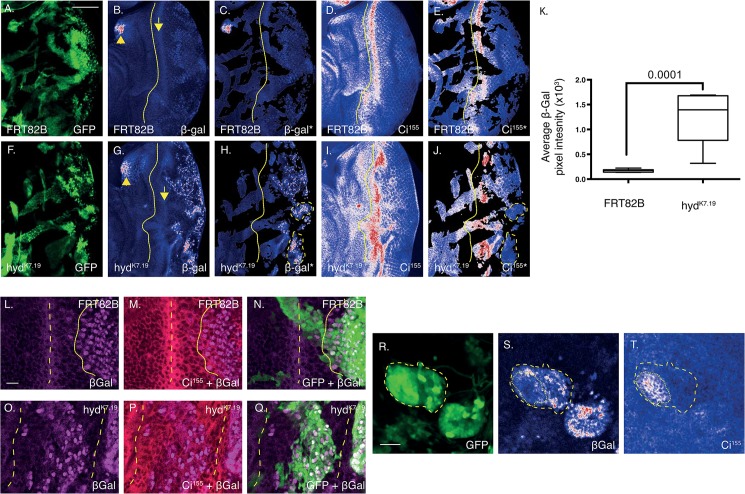

Fig 6. hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibit increased hh-lacZ-associated β-Gal expression within the posterior compartment and DVS-region.

Confocal image sections of FRT82B control (A-E, L-N)) and hyd k7.19 (F-J, O-T) EA discs imaged for direct GFP fluorescence (A,F,N,Q,R), β-Gal (B,C,G,H,L-Q,S) and Ci155 immunofluorescence (D,E,I,J,M,P,T). (A-K) hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibited increased β-Gal expression (H) relative to FRT82B controls (C). Non-clonal regions (GFP—ve regions) were ‘masked off’ to help visualise β-Gal and Ci155 expression only within GFP-positive clones (C,H and E,J, respectively). Yellow dotted lines indicate the division between anterior and posterior compartment (B—E and G-J). Dashed yellow lines indicate regions of high hh expression (H) and corresponding low Ci155 expression (E). (K) Quantification of the β-Gal average pixel intensity of the masked off images. n = 5, s.e.m and indicated p value determined by Student’s t-test. Scale bars = 50μm. (L-Q) hyd k7.19 DVS regions exhibited abnormal β-Gal (O) and Ci155 (P) expression. Dashed lines indicate high Ci155 DVS expression (M,P), which are overlaid onto the other panels. The dotted line marks the anterior front of high β-Gal expression (L), which is overlaid on (M,N). (R-T) Two GFP positive hyd k7.19 clones (R), located in the posterior compartment clearly overexpressed β-Gal (S). Of those clones, only one (R yellow dashed line, which is overlaid onto S,T) also harboured increased Ci155 expression (T). A specific clonal subregion (T, dotted line) with the clone coincided with low β-Gal expression (S, dotted line). Scale bars = 10μm.

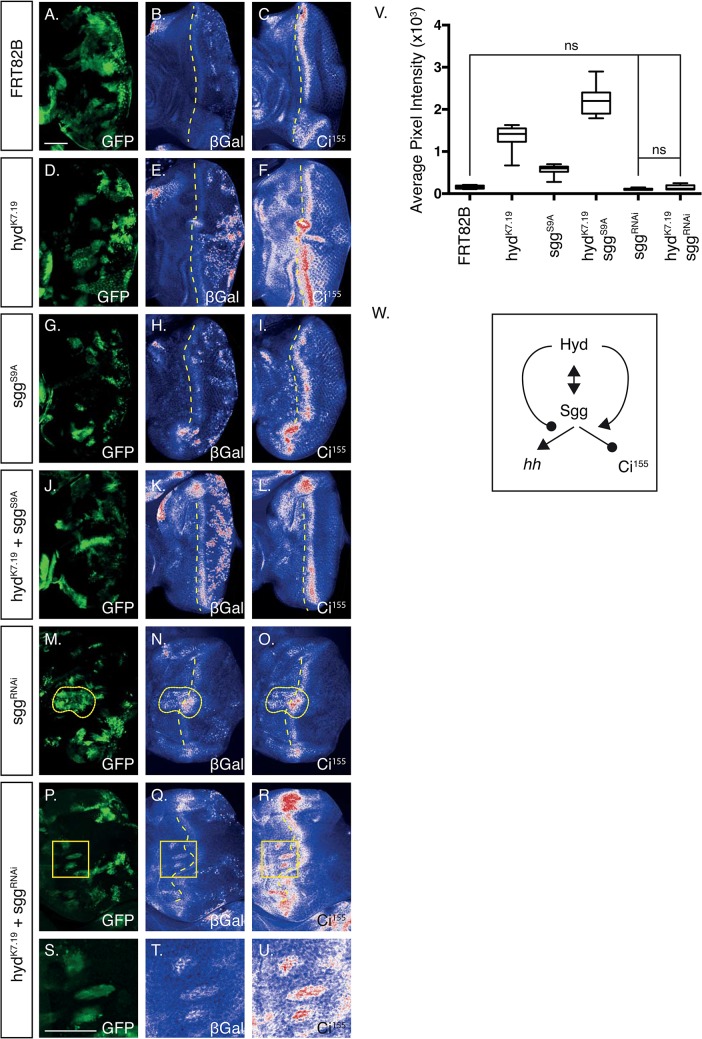

Fig 7. Sgg regulates hh-lacZ expression in both the posterior and anterior compartments.

(A-U) Confocal images of EA disc of the indicated genotypes imaged for GFP (A,D,G,J,M,P,S) fluorescence and β-Gal (B,E,H,K,N,Q,T) and Ci155 (C,F,I,L,O,R,U) immunofluorescence. Dashed lines indicate the division between the anterior and posterior compartments, dotted lines indicate regions of high β-Gal and Ci155 expression within and anterior to the DVS region (N,O, respectively). The boxed regions (P-R) indicate a region harbouring three clones overexpressing β-Gal and Ci155 in the anterior compartment, which are enlarged in (S-U). (V) Boxplots of quantification of the average β-Gal pixel intensity of non-GFP masked off images (not shown). n = >5 for each genotype, s.e.m indicated. Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison tests, which revealed all comparisons to be statistically significant, except those indicated as non-significant (ns). (W) Potential model to explain the effects observed in the posterior EA disc. The double-headed arrow indicates a physical interaction, the single-headed arrow a positive regulatory action and the round-headed arrow a negative regulatory action. Scale bar = 50μm.

hyd K7.19 EA discs exhibit increased hh expression

EA discs bearing hyd k7.19 clones clearly exhibited abnormal Ci155 DVS patterns that suggested improper MF initiation/progression/termination. Due to Hh’s important role in both regulating Ci155 expression and MF initiation and progression, we sought to examine if hh mRNA expression was also abnormal. The altered effects of Ci155 expression outside of hyd k7.19 clones also suggested that an extracellular signalling molecules derived from hyd k7.19 cells could account for cell-non-autonomous effects. Previous work by Lee et al suggested that hyd K7.19 mutant clones spatially misexpressed hh mRNA in the posterior compartment[24]. Such spatial Hh misexpression, and subsequent paracrine-mediated activation of the HhP, could have accounted for the observed ectopic Ci155 expression outside of hyd k7.19 clones. To support this hypothesis, we first wanted to confirm that hyd K7.19 mutant cells spatially, and/or quantitatively, misexpressed hh mRNA. Using a hh lacZ enhancer trap (hhP30)[34] we were able to indirectly assess endogenous hh mRNA expression by determining β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity and expression levels.

Previous work in the wing disc revealed that Ci75 repressed hh expression[37]. We therefore wished to see if expression of unprocessed Ci155 correlated with increased hh expression. To address this we used IF to examine co-localisation of hh-lacZ-derived β-Gal with Ci155 and the GFP signals marking hyd k7.19 clones (Fig 6). To aid quantification, β-Gal and Ci155 images were acquired by fixed acquisition parameters and application of Image J’s “Union Jack” look-up-table, segmenting signal intensities into low (blue), medium (white) and high (red). Analysis of FRT82B control EA discs revealed (i) a thin, low-level dorsal-ventral ‘stripe’ of β-Gal expression in the middle of the posterior domain (Fig 6B, dotted line), (ii) high expression in the anterior-dorsal region (Fig 6B arrowhead) and (iii) low-level expression within the posterior compartment. Please note that non-recombined cells remained heterozygous for hh-lacZ and were therefore capable of expressing β-Gal.

Similar to control discs, hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibited the same low-level dorsal-ventral ‘stripe’ expression (Fig 6G arrow), but had dramatically increased β-Gal expression within the posterior compartment (compare Fig 6B with 6G). To exclusively analyse the regions corresponding to GFP-positive mitotic clones we used thresholding of the GFP channel to mask out the β-Gal and Ci155 signals of non-GFP expression regions (Fig 6C, 6H, 6E and 6J, respectively). Comparing the masked hyd K7.19 images revealed no clear co-localisation of increased Ci155 and β-Gal expression; e.g., two GFP-positive regions exhibiting high hh expression, but low Ci155 expression are indicated (Fig 6H and 6J, dashed lines). Quantification revealed hyd k7.19 EA discs to express β-Gal >10-fold over that of FRT82B control (Fig 6K). In summary, Hyd potently suppressed hh expression in the posterior half of the posterior compartment of EA discs.

Closer examination of the MF region in control EA discs (Fig 6L–6N) revealed the expected increase in β-Gal expression (Fig 6L) 3–5 cell diameters posterior to the Ci155 DVS (Fig 6M)[3]. In contrast, hyd k7.19 EA clones within the presumed MF region (Fig 6O and 6P) were associated with disordered β-Gal expression patterns (Fig 6O) flanked by regions of high DVS-like Ci155 expression (Fig 6P, dashed lines). hyd k7.19 EA discs also exhibited rare posterior hyd K7.19 clones that overexpressed both β-Gal and Ci155 (Fig 6R–6T, dashed line). Yet, even within those clones there appeared to be some degree of mutual exclusivity in Ci155 and β-Gal/hh expression (compare the dotted region within the marked clone in Fig 6S and 6T). In summary, due to the general negative correlation between Ci155 and hh expression, our findings do not support a role for Ci75-mediated suppression of hh in the EA disc. A finding that is in agreement with the genetic approach taken by Lee et al[24].

sgg RNAi rescues hyd k7.19-associated ectopic hh expression

The marked increase in hh gene expression in hyd k7.19 EA discs potentially explained some of the EA disc-wide effects on Ci155 and Ptc expression. However, what remained unclear was how hh expression was being misregulated within hyd k7.19 clones? Although Ci can regulate hh ligand expression in the wing disc[37], we found no positive correlation between increased Ci155 expression and hh overexpression in hyd k7.19 clones (Fig 6H, 6J, 6S and 6T). We next turned our attention to Hyd’s binding partner, Sgg, a kinase implicated in regulating the transcriptional output of diverse signalling pathways[4]. To directly address a role for Sgg in the hyd k7.19–associated overexpression of hh we chose to increase or decrease Sgg function in hyd K7.19 clones. Use of UAS-driven transgenes allowed us to express either an active sgg mutant (sgg S9A) that is refractory to insulin-signalling mediated inhibition[38], or sgg RNAi specifically within FRT82B control or hyd k7.19 clones (Fig 7).

Clonal overexpression of SggS9A alone had no dramatic effect on Ci155 expression patterns either within GFP clones or on the EA disc as a whole (compare Fig 7A and 7C with 7G and 7I). However, there was an apparent increase in β-Gal expression within the posterior compartment (compare Fig 7B with 7H). These observations suggested that SggS9A promoted hh expression in the posterior domain without significantly affecting Ci155 expression. Overexpressing SggS9A within hyd K7.19 clones reduced Ci155 expression to that of control (compare Fig 7C, 7F and 7L) and promoted β-Gal expression within the dorsal-ventral stripe region (compare Fig 7B, 7E and 7K). Therefore, our data indicated that in a hyd k7.19 background SggS9A overexpression suppressed ectopic Ci155 expression and promoted hh expression.

In contrast to sgg S9A, sgg RNAi alone had no obvious effects on β-Gal or Ci155 expression in the posterior, but did increase their expression in regions within, and anterior to, the DVS region (compare Fig 7B, 7N and 7C and 7O, dotted lines, respectively). In a hyd k7.19 background sgg-RNAi reduced Ci155 staining in the posterior, but increased its expression levels within, and anterior to, the DVS (compare Fig 7F and 7R). A very similar pattern was also observed for β-Gal (compare Fig 7E and 7Q). Together these observations indicated that within the posterior compartment, Sgg functions to suppress Ci155 and promote hh expression. Interestingly, rounded anterior clones within hyd k7.19+sgg RNAi EA discs exhibited elevated Ci155 staining that co-localised with increased hh expression (Fig 7P–7R and 7S–7U). These observations suggested that within the anterior compartment, Sgg functions to repress both Ci155 and hh expression.

The masking technique described in Fig 6 allowed quantification of clonal β-Gal average intensities within the posterior compartment. Analysis revealed SggS9A overexpression caused a two- and >20-fold increase in β-Gal expression in comparison to hyd k7.19 or FRT82B control discs, respectively (Fig 7V). The increased β-Gal expression in hyd k7.19 + sgg S9A EA discs indicated potential co-operation between loss of Hyd and gain of Sgg function in promoting hh/β-Gal expression. In agreement with the IF images, sgg RNAi in a hyd k7.19 background reduced hh-β-Gal expression levels back to that of FRT82B control levels. In summary, our image and quantification data indicated that Sgg regulated hh expression in both the posterior and anterior compartments and modified hyd k7.19-associated ectopic Ci155 and hh expression patterns.

Taken together our data suggested that, within the central and posterior regions, loss of Hyd function cell autonomously (i) promoted Sgg-mediated promotion of hh expression—that potentially accounted for the increased Ci155 expression outside of hyd k7.19 clones and (ii) inhibited Sgg-mediated repression of Ci155 expression—that potentially contributed to the increased Ci155 expression within hyd k7.19 clones. Please note that our observations cannot exclude a role for autocrine/paracrine Hh-mediated increases in Ci155 expression within hyd k7.19 clones. A model of the physical and functional relationships between Hyd and Sgg is depicted in Fig 7W.

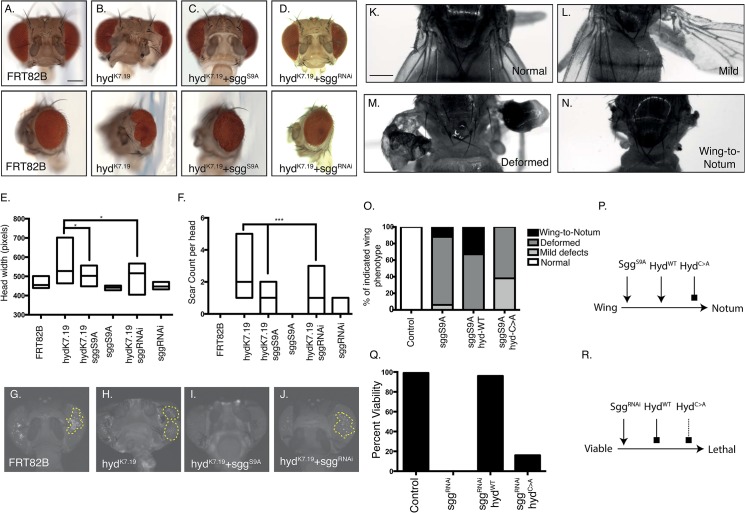

sgg RNAi rescues the hyd K7.19 adult eye phenotype

Next we wished to determine if modulation of Sgg activity modified the adult hyd K7.19 head phenotype (Fig 8A–8D). Surprisingly both sgg S9A and sgg RNAi rescued the hyd K7.19 phenotype (compare Fig 8B with 8C and 8D, respectively). Quantification of the phenotypic effects revealed a significant decrease upon perturbation of sgg function (Fig 8E and 8F, respectively), with sgg S9A resulting in the more robust rescue. To ensure that mutant clones were persisting and contributing to adult structures we examined the adults’ heads for GFP signals (Fig 8G–8J). An absence of GFP positive clones in the hyd k7.19+sgg S9A adult heads (Fig 8I) suggested that the combined loss of hyd and gain of sgg function (hyd k7.19 + sgg S9A) eliminated the mutant cells from the developing EA disc/head. Hence, it appears that sgg loss of function (hyd k7.19 +sgg RNAi), rather than eliminating cells, actively rescued the signalling defects associated with the hyd k7.19 phenotype. Comparing the molecular phenotypes of the SggS9A and sgg RNAi rescue EA discs (Fig 7J–7L and 7P–7U, respectively) revealed that the reduction in hh expression correlated with the ‘true’ phenotypic rescue by sgg RNAi.

Fig 8. Sgg and Hyd genetically interact to govern animal viability and head and wing development.

(A-J) Sgg perturbation modifies the hyd k7.19 head phenotype. (A-D) Brightfield images of adult Drosophila heads of the indicated genotypes shown either ‘head on’ (upper panels) or ‘side on’ (lower panels). Both gain (C) and loss (D) of sgg function appeared to rescue the hyd k7.19 phenotype. Boxplots indicating head width (E, n = ≥8 for each genotype) and counts of eye scars (F, n = ≥8 for each genotype) of the indicated genotypes, with statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA (E) and Fishers exact test (F) revealed statistical significance (asterisks). (G-J) Representative GFP fluorescent signals in adult Drosophila heads of the indicated genotypes revealed only hyd k7.19 +sgg S9A animals lack a GFP signal (n = ≥4 for each genotype). Scale bars = 175μm. (K-P) hyd WT overexpression promotes the sgg S9A-mediated wing phenotype. (K-N) Brightfield images of adult Drosophila wings showing (K) normal, (L) mildly deformed, (M) severely deformed and (N) wing-to-notum phenotypes. (O) Percentage of adult wing phenotypes of vg-GAL4 flies expressing the indicated transgenes, revealing that the hyd WT transgene enhanced, and the hyd C>A transgene suppressed the severity of the sgg S9A wing defects (n ≥12 for each genotype). (P) Model showing the genetic interaction between sgg S9A and hyd UAS-transgenes with respect to the wing-to-notum phenotype. Arrows indicate promotion and blockhead arrows inhibition. (Q-R) hyd WT overexpression rescues sgg RNAi-mediated embryonic lethality. Percentage viability of sca-GAL4 flies expressing the indicated transgenes revealed a >95% rescue of embryonic lethality upon co-expression with the UAS-hyd WT, but not UAS-hyd C>A, transgene (16 individual crosses per genotype). (R) Model showing the genetic interaction between sgg and hyd UAS-transgenes. Arrows indicate promotion, blockhead arrows inhibition and dotted blockhead arrow weak inhibition. Scale bar = 250μm.

hyd and sgg genetically interact to regulate animal viability and wing development

Our work in the eye disc indicated that hyd and sgg exhibited a complex genetic interaction to influence EA disc development. We next used UAS-GAL4-based overexpression and RNAi studies to confirm that hyd and sgg genetically interacted in other imaginal discs/organs. The wing disc was chosen based upon hyd K3.5 clones phenocopying the Ci155 and hh effects observed in the EA disc[24] and importance Hh signalling in its development[39]. SggS9A overexpression in the developing wing disc by the vestigal-GAL4 (vg-GAL4) driver (Fig 8K–8P) resulted in deformed wings (Fig 8L and 8M) and with less frequency wing-to-notum transformation(Fig 8N)[38]. Co-expression of UAS-hyd WT enhanced the SggS9A phenotype resulting in a significant increase in the percentage of flies exhibiting wing-to-notum transformation, whereas E3 defective UAS-hyd C>A suppressed the SggS9A phenotype (Fig 8O). These observations suggested that Sgg and HydWT, but not HydC>A, co-operated in promoting wing-to-notum transformation (Fig 8P). A similar positive relationship was also observed when using scaborous-GAL4 (sca-GAL4) to drive sgg-RNAi in a number of organs that includes the wing disc[40]. Remarkably, the embryonic lethality associated with sgg-RNAi was effectively rescued by co-expression of UAS-hyd WT, but not UAS-hyd C>A (Fig 8Q). These observations further support a strong genetic interaction between hyd and sgg in diverse aspects of Drosophila development. Additionally, it appeared that HydWT, but not HydC>A, efficiently functioned to potentially promote Sgg function (Fig 8R). Please note that our vg- and sca-GAL4 studies suggested that Hyd promoted Sgg function, yet in the EA Hyd appeared to suppress Sgg function. Potential explanations of this apparent contradiction are detailed in the discussion below.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results identified a genetic and physical interaction between hyd/Hyd and sgg/Sgg, as well as a role in regulating imaginal disc development, embryonic viability and hh and Ci155 expression.

Discussion

Sgg and Hyd regulate hh expression

Both Hyd and Sgg regulate hh expression in the posterior domain, with Sgg promoting and Hyd suppressing hh expression. Our epistasis experiments in the EA disc with the sgg S9A and sgg RNAi transgenes also revealed that sgg functions either downstream of, or parallel to, hyd in regulating hh expression. Therefore within the posterior EA disc we suggest that Hyd normally represses Sgg’s ability to promote hh expression. Combined with the fact that the two proteins physically interact, we believe that they function in the same signalling pathway, albeit with opposing effects on hh expression.

The observed general increase in Ci155 expression within hyd k7.19 discs located near the DVS provided a potential mechanism of regulating hh expression[37]. While we did not directly address Ci75 expression levels, we may infer that increased Ci155 expression may have resulted from decreased Ci75 generation and a subsequent de-repression of hh expression. Our observation that hyd k7.19 clones located well within the posterior compartment exhibited increased hh, but low Ci155 expression, failed to support a role Ci75-mediated regulation of hh expression. Furthermore, SggS9A overexpression, which would be predicted to promote Ci75 production, also promoted hh expression.

SggS9A’s ability to promote ectopic hh expression raised the possibility that transcriptional control via other signalling pathway could also be involved. GSK3β governs the activity of multiple transcription factors[4, 41] that could potentially influence hh transcription. Of hh’s known transcriptional (Engrailed[42], Master of Thickveins[43], Serpent[44]) and epigenetic regulators (PRC1/2 and Trithorax[45] and Kismet[46]) none are reported to bind to Hyd or Sgg (Biogrid/INTact databases). Hence there is no clear candidate to potentially explain how Sgg/GSK3β’s might regulate hh expression.

Hyd Suppresses Ci155 expression

Within hyd k7.19 clone-bearing EA discs, elevated Hh-mediated paracrine signalling most likely accounted for the increased Ci155 expression outside of hyd k7.19 clones. Whereas within hyd k7.19 clones themselves, Hyd can cell autonomously influence Ci155 expression levels independent of its effects on hh transcription[24]. We clearly observed marked changes in Ci155 expression within hyd k7.19 clones relative to surrounding control cells, which are presumably exposed to similar local Hh expression levels. Therefore, cell-intrinsic genetic differences between cells, rather than distinct Hh levels, potentially explained the Ci155 expression patterns. We hypothesise that cell autonomous effects on Ci155 expression observed within hyd k7.19 clones may be due to reduced Sgg-mediated Ci155 proteolysis. In summary, we believe that Ci155 expression levels across the hyd k7.19 EA disc are governed by both Hh-ligand-dependent and-independent mechanism that may both rely on Hyd and Sgg function.

Ci155 expression is post-translationally controlled by two distinct Cullin-based E3 complexes that are distinguished by their substrate-specificity factors Slmb[7] and Rdx[8, 9] and their spatially restricted actions. In general, the Cul-1Slmb complex promotes Ci155 processing in the anterior compartment, whereas the Cul-3Rdx complex promotes Ci155 degradation in the posterior. However, Cul-1 and-3 activity overlap around the MF[47], which raises the possibility of both Cul-1Slmb-mediated Ci155 processing and Cul-3Rdx-mediated Ci155 degradation[47, 48] occurring within the same cell. Due to the hyd k7.19 EA discs’ abnormal Ci155 DVS patterns (i.e., broader, irregular, posterior extensions) it was possible that Cul-associated activities were also spatially abnormal around an irregular morphogenetic furrow. Hence, we hypothesise that misexpression of Cul-associated E3 activities may underlie the numerous Ci155 expression defects observed within hyd k7.19 clones. EDD’s ability to bind Cul-3[49] also supports a potential role for Hyd in influencing Cul-3Rdx-mediated Ci155 ubiquitylation and degradation.

Hyd regulates imaginal disc development

hyd k7.19 EA discs exhibiting ectopic hh expression would lead to abnormal paracrine Hh signalling and irregular MF progression. Disruption of such an important morphological landmark as the MF may have altered the discs’ anterior-posterior, dorsal-ventral and lateral-medial axes to disrupt spatial information and consequentially alter cell fates (e.g., eye to head capsule). Our studies in different imaginal discs and tissues clearly identify a strong genetic interaction between hyd and sgg in controlling Drosophila development. Due to the essential roles for Hh signalling in development, we hypothesise that defects in HhP activity underlies a significant component of the observed mutant phenotypes.

Within the EA disc, Wingless (Wg) and Hh morphogen signalling antagonise each other’s actions to specify the EA discs’ cellular fate and promote development of distinct adult head structures[50]. As in the EA disc, both morphogen signalling pathways also play essential role in wing disc development[3, 51]. Due to Sgg’s key roles in both morphigen signalling pathways perturbed Wg signalling could also contribute to the hyd k7.19 mutant phenotype. The previously reported partial rescue of the hyd K3.5 adult head phenotype upon loss of hh function[24], clearly suggested the additional involvement of other Hh-ligand-independent effects. Within the HhP, Hyd’s potential ability to influence Sgg-mediated Ci155 expression could be one such Hh-ligand-independent component. However, an effect totally independent of the HhP, such as the Wg pathway, could also contribute to the hyd K7.19 adult head phenotype.

While Hh plays an important role in wing development, abnormal Wg signalling plays a known role in the wing-to-notum transformation[38]. EDD’s ability to affect β-catenin activity[30, 52] supports a potential evolutionarily conserved role for Hyd in Wg pathway signalling. Therefore, future work should focus on simultaneously investigating both Wg- and Hh-mediated signalling in hyd mutant tissue. Although we are uncertain as to exact molecular mechanisms involved, our sequencing of the hyd k7.19 allele, in combination with our hyd transgene experiments in the eye and wing discs, clearly support an important role for Hyd’s HECT-associated E3 activity in regulating Sgg function and controlling Drosophila development.

Epistatic relationship between hyd and sgg

At the morphological level the epistatic relationships observed in the eye and wing disc appear contradictory. In the eye, Hyd appeared to repress Sgg function while in the wing disc it appeared to promote Sgg function. A simple explanation may reside in technical differences between generating cells totally lacking full-length Hyd (hyd k7.19) versus those experiencing a reduction/overexpression. The difference in the two systems is clearly demonstrated by an absence of an adult head phenotype upon EA disc clonal overexpression of SggS9A compared to the dramatic adult wing phenotypes upon vg-GAL4-mediated SggS9A overexpression.

An alternative explanation resides in tissue-specific differences between eye and wing imaginal discs. This notion is supported by the striking fact that hyd hemizyogous mutant animals harbour hyperplastic wing and hypoplastic haltere discs[11]. Hence loss of Hyd function can produce diametrically opposed effect in different types of imaginal discs. Additionally, the functional relationship between Hyd and Sgg is not a simple one, whereby Hyd may (i) promote Sgg-mediated repression of Ci155 expression and yet (ii) inhibit Sgg-mediated promotion of hh expression (see Fig 7W). Taking the EA disc as a whole, Hyd can apparently both promote and inhibit distinct functional aspects of Sgg and Hedgehog signalling. Discrepancies at the morphological level may therefore potentially reflect Hyd’s differential ability to promote and inhibit distinct Sgg functions at the molecular level.

With tissue-specific requirements in mind, development of a particular tissue may be more susceptible to disruption of one of Hyd/Sgg’s Hh-associated functions than the other. For example, the genetic epistasis observed in the EA disc suggested that regulation of hh was the critical determinant for the disc’s correct development—highlighting Hyd’s importance in repressing Sgg-mediated hh expression (left arm of Fig 7W). In contrast, Hyd’s ability to promote Sgg-mediated inhibition of Ci155 (right arm of Fig 7W) may be the critical determinant for promoting abnormal wing development.

In summary our findings implicate both Sgg and Hyd as important regulators of hh ligand expression, HhP activity and imaginal disc development. Hyd may influence Sgg to utilise mechanistically independent actions to control initiation of (hh expression) and the response to (Ci155 expression) Hedgehog signalling. We hypothese that Hyd and Sgg act to establish distinct Hedgehog signalling cell states—e.g., (A) cells capable of producing Hh and but not responding to Hh stimulation and (B) cells only being able to respond to, but not produce, Hh. Such rigid cell states could help establish and subsequently enforce spatial divisions, whereas transitions between them could also allow morphogenetic elements like the MF to function as it moves across the EA disc.

Hyd’s ability to regulate Hh signalling provides it with the potential means to govern important cellular signalling pathway involved in both animal development and adult tissue homeostasis. These potential abilities may help to explain the dramatic phenotypes observed in homozygous hyd K7.19 larvae[11], Ubr5 null mice[53], conditionally mutant adult Ubr5 mice (MD, manuscripts in preparation) and human cancers[54–56].

Supporting Information

Confocal images of UAS-hyd WT; FRT82B hyd k7.19 EA discs imaged, left to right, for direct GFP fluorescence, Ci155 and Ptc immunofluorescence and the indicated combinations. These discs exhibit relatively normal Ci155 and Ptc expression patterns, indicating an effective rescue of the hyd k7.19 phenotype by overexpression of HydWT.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Bloomington Stock Centre, Drosophila Genetics Resource Centre, Addgene, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Drosophila Genomics Resource Centre (supported by NIH grant 2P40OD010949–10A1), Mary Anne Price, Jessica Treisman, Bob Holmgreen, Marcos Vidal and Tom Kornberg for materials and fly strains. Paul Perry and Matthew Pearson for imaging assistance.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council New Investigator Award BB/H0128691/1 (MD, FS), the Medical Research Council RA1734 (SM) and an ERASMUS undergraduate placement award (MM). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Pan Y, Bai CB, Joyner AL, Wang B. Sonic hedgehog signaling regulates Gli2 transcriptional activity by suppressing its processing and degradation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26(9):3365–77. Epub 2006/04/14. 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3365-3377.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Briscoe J, Therond PP. The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2013;14(7):416–29. Epub 2013/05/31. 10.1038/nrm3598 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker NE. Patterning signals and proliferation in Drosophila imaginal discs. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2007;17(4):287–93. Epub 2007/07/13. 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sutherland C. What Are the bona fide GSK3 Substrates? Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:505607 Epub 2011/06/02. 10.4061/2011/505607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Price MA, Kalderon D. Proteolysis of the Hedgehog signaling effector Cubitus interruptus requires phosphorylation by Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 and Casein Kinase 1. Cell. 2002;108(6):823–35. Epub 2002/04/17. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jia J, Amanai K, Wang G, Tang J, Wang B, Jiang J. Shaggy/GSK3 antagonizes Hedgehog signalling by regulating Cubitus interruptus. Nature. 2002;416(6880):548–52. Epub 2002/03/26. 10.1038/nature733 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiang J, Struhl G. Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature. 1998;391(6666):493–6. Epub 1998/02/14. 10.1038/35154 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kent D, Bush EW, Hooper JE. Roadkill attenuates Hedgehog responses through degradation of Cubitus interruptus. Development. 2006;133(10):2001–10. Epub 2006/05/03. 10.1242/dev.02370 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang Q, Zhang L, Wang B, Ou CY, Chien CT, Jiang J. A hedgehog-induced BTB protein modulates hedgehog signaling by degrading Ci/Gli transcription factor. Developmental cell. 2006;10(6):719–29. Epub 2006/06/03. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sriram SM, Kim BY, Kwon YT. The N-end rule pathway: emerging functions and molecular principles of substrate recognition. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2011;12(11):735–47. Epub 2011/10/22. 10.1038/nrm3217 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mansfield E, Hersperger E, Biggs J, Shearn A. Genetic and molecular analysis of hyperplastic discs, a gene whose product is required for regulation of cell proliferation in Drosophila melanogaster imaginal discs and germ cells. Dev Biol. 1994;165(2):507–26. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kozlov G, Nguyen L, Lin T, De Crescenzo G, Park M, Gehring K. Structural basis of ubiquitin recognition by the ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain of the ubiquitin ligase EDD. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(49):35787–95. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matta-Camacho E, Kozlov G, Li FF, Gehring K. Structural basis of substrate recognition and specificity in the N-end rule pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(10):1182–7. Epub 2010/09/14. 10.1038/nsmb.1894 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matta-Camacho E, Kozlov G, Menade M, Gehring K. Structure of the HECT C-lobe of the UBR5 E3 ubiquitin ligase. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2012;68(Pt 10):1158–63. Epub 2012/10/03. 10.1107/S1744309112036937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang T, Cronshaw J, Kanu N, Snijders AP, Behrens A. UBR5-mediated ubiquitination of ATMIN is required for ionizing radiation-induced ATM signaling and function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(33):12091–6. Epub 2014/08/06. 10.1073/pnas.1400230111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okamoto K, Bartocci C, Ouzounov I, Diedrich JK, Yates JR 3rd, Denchi EL. A two-step mechanism for TRF2-mediated chromosome-end protection. Nature. 2013;494(7438):502–5. Epub 2013/02/08. 10.1038/nature11873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gudjonsson T, Altmeyer M, Savic V, Toledo L, Dinant C, Grofte M, et al. TRIP12 and UBR5 suppress spreading of chromatin ubiquitylation at damaged chromosomes. Cell. 2012;150(4):697–709. Epub 2012/08/14. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.039 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Su H, Meng S, Lu Y, Trombly MI, Chen J, Lin C, et al. Mammalian hyperplastic discs homolog EDD regulates miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Molecular cell. 2011;43(1):97–109. Epub 2011/07/06. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reid MA, Wang WI, Rosales KR, Welliver MX, Pan M, Kong M. The B55alpha subunit of PP2A drives a p53-dependent metabolic adaptation to glutamine deprivation. Molecular cell. 2013;50(2):200–11. Epub 2013/03/19. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scialpi F, Mellis D, Ditzel M. EDD, a ubiquitin-protein ligase of the N-end rule pathway, associates with spindle assembly checkpoint components and regulates the mitotic response to nocodazole. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290(20):12585–94. Epub 2015/04/03. 10.1074/jbc.M114.625673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Munoz MA, Saunders DN, Henderson MJ, Clancy JL, Russell AJ, Lehrbach G, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase EDD regulates S-phase and G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoints. Cell cycle. 2007;6(24):3070–7. Epub 2007/12/13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smits VA. EDD induces cell cycle arrest by increasing p53 levels. Cell cycle. 2012;11(4). Epub 2012/02/07. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benavides M, Chow-Tsang LF, Zhang J, Zhong H. The novel interaction between microspherule protein Msp58 and ubiquitin E3 ligase EDD regulates cell cycle progression. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1833(1):21–32. Epub 2012/10/17. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee JD, Amanai K, Shearn A, Treisman JE. The ubiquitin ligase Hyperplastic discs negatively regulates hedgehog and decapentaplegic expression by independent mechanisms. Development. 2002;129(24):5697–706. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ditzel M, Broemer M, Tenev T, Bolduc C, Lee TV, Rigbolt KT, et al. Inactivation of effector caspases through nondegradative polyubiquitylation. Mol Cell. 2008;32(4):540–53. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24(5):251–4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee JJ, von Kessler DP, Parks S, Beachy PA. Secretion and localized transcription suggest a role in positional signaling for products of the segmentation gene hedgehog. Cell. 1992;71(1):33–50. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Legent K, Treisman JE. Wingless signaling in Drosophila eye development. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;469:141–61. Epub 2008/12/26. 10.1007/978-1-60327-469-2_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallet A, Rodriguez R, Ruel L, Therond PP. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog is required for trafficking and movement, revealing an asymmetric cellular response to hedgehog. Developmental cell. 2003;4(2):191–204. Epub 2003/02/15. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hay-Koren A, Caspi M, Zilberberg A, Rosin-Arbesfeld R. The EDD E3 ubiquitin ligase ubiquitinates and up-regulates beta-catenin. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(3):399–411. Epub 2010/12/02. 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lim NS, Kozlov G, Chang TC, Groover O, Siddiqui N, Volpon L, et al. Comparative peptide binding studies of the PABC domains from the ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase HYD and poly(A)-binding protein. Implications for HYD function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):14376–82. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Motzny CK, Holmgren R. The Drosophila cubitus interruptus protein and its role in the wingless and hedgehog signal transduction pathways. Mechanisms of development. 1995;52(1):137–50. Epub 1995/07/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blanco J, Seimiya M, Pauli T, Reichert H, Gehring WJ. Wingless and Hedgehog signaling pathways regulate orthodenticle and eyes absent during ocelli development in Drosophila. Developmental biology. 2009;329(1):104–15. Epub 2009/03/10. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ma C, Zhou Y, Beachy PA, Moses K. The segment polarity gene hedgehog is required for progression of the morphogenetic furrow in the developing Drosophila eye. Cell. 1993;75(5):927–38. Epub 1993/12/03. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roignant JY, Treisman JE. Pattern formation in the Drosophila eye disc. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53(5–6):795–804. Epub 2009/06/27. 10.1387/ijdb.072483jr [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JJ, Ekker SC, von Kessler DP, Porter JA, Sun BI, Beachy PA. Autoproteolysis in hedgehog protein biogenesis. Science. 1994;266(5190):1528–37. Epub 1994/12/02. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Methot N, Basler K. Hedgehog controls limb development by regulating the activities of distinct transcriptional activator and repressor forms of Cubitus interruptus. Cell. 1999;96(6):819–31. Epub 1999/04/02. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Papadopoulou D, Bianchi MW, Bourouis M. Functional studies of shaggy/glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation sites in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24(11):4909–19. Epub 2004/05/15. 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4909-4919.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gradilla AC, Guerrero I. Hedgehog on the move: a precise spatial control of Hedgehog dispersion shapes the gradient. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2013;23(4):363–73. Epub 2013/06/12. 10.1016/j.gde.2013.04.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guo M, Jan LY, Jan YN. Control of daughter cell fates during asymmetric division: interaction of Numb and Notch. Neuron. 1996;17(1):27–41. Epub 1996/07/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henderson MJ, Russell AJ, Hird S, Munoz M, Clancy JL, Lehrbach GM, et al. EDD, the human hyperplastic discs protein, has a role in progesterone receptor coactivation and potential involvement in DNA damage response. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(29):26468–78. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tabata T, Eaton S, Kornberg TB. The Drosophila hedgehog gene is expressed specifically in posterior compartment cells and is a target of engrailed regulation. Genes & development. 1992;6(12B):2635–45. Epub 1992/12/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bejarano F, Perez L, Apidianakis Y, Delidakis C, Milan M. Hedgehog restricts its expression domain in the Drosophila wing. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(8):778–83. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tokusumi Y, Tokusumi T, Stoller-Conrad J, Schulz RA. Serpent, suppressor of hairless and U-shaped are crucial regulators of hedgehog niche expression and prohemocyte maintenance during Drosophila larval hematopoiesis. Development. 2010;137(21):3561–8. Epub 2010/09/30. 10.1242/dev.053728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maurange C, Paro R. A cellular memory module conveys epigenetic inheritance of hedgehog expression during Drosophila wing imaginal disc development. Genes Dev. 2002;16(20):2672–83. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Terriente-Felix A, Molnar C, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, de Celis JF. A conserved function of the chromatin ATPase Kismet in the regulation of hedgehog expression. Developmental biology. 2011;350(2):382–92. Epub 2010/12/15. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ou CY, Lin YF, Chen YJ, Chien CT. Distinct protein degradation mechanisms mediated by Cul1 and Cul3 controlling Ci stability in Drosophila eye development. Genes & development. 2002;16(18):2403–14. Epub 2002/09/17. 10.1101/gad.1011402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baker NE, Bhattacharya A, Firth LC. Regulation of Hh signal transduction as Drosophila eye differentiation progresses. Developmental biology. 2009;335(2):356–66. Epub 2009/09/19. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bennett EJ, Rush J, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Dynamics of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase network revealed by systematic quantitative proteomics. Cell. 2010;143(6):951–65. Epub 2010/12/15. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Royet J, Finkelstein R. Establishing primordia in the Drosophila eye-antennal imaginal disc: the roles of decapentaplegic, wingless and hedgehog. Development. 1997;124(23):4793–800. Epub 1998/01/15. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Klein T. Wing disc development in the fly: the early stages. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2001;11(4):470–5. Epub 2001/07/13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ohshima R, Ohta T, Wu W, Koike A, Iwatani T, Henderson M, et al. Putative tumor suppressor EDD interacts with and up-regulates APC. Genes Cells. 2007;12(12):1339–45. Epub 2007/12/14. 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01138.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Saunders DN, Hird SL, Withington SL, Dunwoodie SL, Henderson MJ, Biben C, et al. Edd, the murine hyperplastic disc gene, is essential for yolk sac vascularization and chorioallantoic fusion. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(16):7225–34. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. O'Brien PM, Davies MJ, Scurry JP, Smith AN, Barton CA, Henderson MJ, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase EDD is an adverse prognostic factor for serous epithelial ovarian cancer and modulates cisplatin resistance in vitro. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(6):1085–93. Epub 2008/03/20. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fuja TJ, Lin F, Osann KE, Bryant PJ. Somatic mutations and altered expression of the candidate tumor suppressors CSNK1 epsilon, DLG1, and EDD/hHYD in mammary ductal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64(3):942–51. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Meissner B, Kridel R, Lim RS, Rogic S, Tse K, Scott DW, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR5 is recurrently mutated in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(16):3161–4. Epub 2013/02/15. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478834 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confocal images of UAS-hyd WT; FRT82B hyd k7.19 EA discs imaged, left to right, for direct GFP fluorescence, Ci155 and Ptc immunofluorescence and the indicated combinations. These discs exhibit relatively normal Ci155 and Ptc expression patterns, indicating an effective rescue of the hyd k7.19 phenotype by overexpression of HydWT.

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.