Abstract

New York City has experienced the largest HIV epidemic among persons who use psychoactive drugs. We examined progress in placing HIV seropositive persons who inject drugs (PWID) and HIV seropositive non-injecting drug users (NIDU) onto antiretroviral treatment (ART) in New York City over the last 15 years. We recruited 3511 PWID and 3543 NIDU from persons voluntarily entering drug detoxification and methadone maintenance treatment programs in New York City from 2001 to 2014. HIV prevalence declined significantly among both PWID and NIDU. The percentage who reported receiving ART increased significantly, from approximately 50% (2001-2005) to approximately 75% (2012-2014). There were no racial/ethnic disparities in the percentages of HIV seropositive persons who were on ART. Continued improvement in ART uptake and TasP and maintenance of other prevention and care services should lead to an “End of the AIDS Epidemic” for persons who use heroin and cocaine in the New York City.

Keywords: Persons who inject drugs, Non-injection drug users, Treatment as prevention, HIV, antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Treatment as prevention (TasP) is a component in combined prevention and care for persons with HIV/AIDS. The basic idea of TasP is that HIV seropositive persons receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) and achieving viral suppression will not be likely to transmit HIV to others even if they engage in risk behaviors. Thus, having HIV seropositive persons on ART would not only protect their individual health but also reduce further transmission of HIV. New US guidelines encourage all HIV positive persons to begin ART regardless of CD4 count [1]. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYCDOHMH) announced a goal of having 80% of newly diagnosed HIV seropositive persons achieve viral suppression within 12 months of initial diagnosis [2]. New York State has an initiative to “End the AIDS Epidemic”—reducing the number of new HIV infections from the current 3000 per year to 750 per year by 2020, with increasing the numbers of HIV positive persons at viral suppression as a major component of the initiative [3]. If ART/TasP were truly provided to all or almost all HIV infected persons in the US, then it should lead to sufficiently reduced HIV transmission that we would have an “AIDS free generation” [4] with very few new HIV infections, and “end the AIDS epidemic,” and get close to the WHO aspirational goal of “zero new infections”[5].

As a nation, the US has made some progress in getting HIV seropositive persons on ART and to viral suppression but is still far from having a high percentage of HIV seropositive persons on ART and at viral suppression. In a recent analysis of the “treatment cascade” from initial HIV testing to engagement in care to initiation of ART to adherence and achieving viral suppression, 82% of HIV seropositives have been tested, 33% are on ART and 25% are at viral suppression [6]. There are multiple difficulties in effectively providing ART/TasP to persons who use psychoactive drugs including the problems in daily living created by drug dependence, poverty, stigma associated with substance use and mistrust of the medical establishment among substance users, as well as gaps in health care access [7]. These problems can occur at all stages of the HIV treatment cascade, and many HIV seropositive persons with substance use disorders may have additional problems, such as unstable housing or low employment. Others have also noted the need for accessible substance use treatment and the need for integrated services in order to achieve viral suppression in HIV positive persons with substance use disorders [8-10].

In this report, we examine provision of ART to a large sample of HIV positive persons who inject drugs (PWID) and non-injecting drug users (NIDU) in New York City. New York City has experienced the largest HIV epidemics among PWID and NIDU of any city in the world [11]. New York has also made strong political and public health commitments to reducing HIV infection. In addition to the City policy goal of having 80% of persons with newly diagnosed HIV infection achieving viral suppression within 12 months of diagnosis, the Governor of New York recently announced an initiative to “End the AIDS Epidemic” in the state, with a goal of reducing newly diagnosed HIV infections from over 3000 in 2012, (the most recent data available) [12] to 750 in 2020. New York may thus provide an instructive example of the potential for implementation of TasP for PWID and NIDU, and whether the provision of ART and TasP, in combination with other prevention interventions, may lead to “an AIDS free generation” among persons who use drugs in the New York City.

Methods

The data reported here were derived from ongoing analyses of data collected from drug users entering the Mount Sinai Beth Israel drug detoxification and methadone maintenance programs in New York City. The methods for this “Risk Factors” study have been previously described in detail [13,14] so only a summary will be presented here. The programs are both large (approximately 5000 admissions per year in the detoxification program and approximately 1000 new admissions per year and 6000 patients participating in methadone treatment at any point in time) and serve New York City as a whole. There were no changes in the requirements for entrance into the program over the time periods for the data presented here.

Both injecting and non-injecting drug users entering the detoxification and methadone maintenance programs were eligible to participate in the study. Hospital records and the questionnaire results were checked for consistency on route of drug administration and subjects were examined for physical evidence of injecting.

In the detoxification program, research staff visited the general admission wards of the program in a preset order and examined all intake records of a specific ward to construct lists of patients admitted within the prior 3 days. All of the patients on the list for the specific ward were then asked to participate in the study. After all of the patients admitted to a specific ward in the 3 day period were asked to participate and interviews have been conducted among those who agreed to participate, the interviewer moved to the next ward in the preset order. As there was no relationship between the assignment of patients to wards and the order that the staff rotated through the wards, these procedures produced an unbiased sample of persons who entered the detoxification program. In the methadone program, newly admitted patients (those admitted in the previous month) were asked to participate in the research. In both programs, willingness to participate was high, with approximately 95% of those asked agreeing to participate.

Written informed consent was obtained and a trained interviewer administered a structured questionnaire covering demographics, drug use, sexual risk behavior, and use of HIV prevention services. Most drug use and HIV risk behavior questions referred to the 6 months prior to the interview.

After completing the interview, each participant was seen by a counselor for HIV pretest counseling and serum collection. HIV testing was conducted at the New York City Department of Health Laboratory using a commercial, enzyme-linked, immunosorbent assays (EIA) test with Western blot confirmation (BioRad Genetic Systems HIV-1-2+0 EIA and HIV-1 Western Blot, BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

In 2001, the questions with respect to HIV testing and ART were revised to be more inclusive of different types of ART. The specific questions on HIV testing were “Have you ever been tested for HIV?” and, if yes, “Have you ever gotten a positive HIV test result?” and, for those who answered that they had received a positive HIV test, the single question on ART was “During the last six months, have you taken any medication such as AZT, DDI, protease inhibitors, NNRTIs, HAART, or some other drug to combat HIV/AIDS?” We did not include a measure of adherence due to the problem of finding a suitable recall period for persons transitioning from living in the community to an inpatient facility. Linkage to care and the importance of adherence to anti-retroviral medication were discussed in the counseling sessions for HIV seropostive participants. The data in this report are from 2001, after the HIV testing and ART questions were modified, to September 2014.

Subjects were permitted to participate multiple times in the study, though only once in any calendar year. We used data from subjects who participated in different years in the analyses presented here, as those subjects were members of the population of interest in the different years. Only about 3% of the subjects in any year were repeat participants, as a result, these subjects would have only a very limited influence on the results.

The Stata statistical programs [15] were used for statistical analyses. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Mount Sinai Beth Israel.

Results

Demographic characteristics, recent drug use behavior and HIV status

Tables 1a and 1b present HIV status by demographic characteristics (including heterosexual males, females, and men-who-have-sex-with men (MSM) and drug use behavior, separately for PWID and NIDU. (This seroprevalence is based on HIV testing, not on self-report of being HIV seropositive.) There are clear disparities, with African-Americans, Latino/as (chisq = 87.2, df=2, p=0.000 among PWID; and chisq = 22.6, df=2, p=0.000 among NIDU), females and MSM (chisq = 44.7, df=2, p=0.000 among PWID; and chisq = 198.2, df=2, p=0.000 among NIDU) having higher HIV prevalence. Older participants were also more likely to be HIV seropositive (chisq = 51.1, df=1, p=0.000 among PWID; and chisq = 4.7, df=2, p=0.031 among NIDU). There were also a number of differences in HIV status by drug use behaviors in the 6 months prior to the interview. As the HIV seropositive subjects were likely to have been infected well before the 6 months prior to the interview, caution is needed in interpreting these relationships.

Table 1a.

HIV serostatus by demographics and drug use characteristics among PWID (2001-2014)

| Total N (%) | Chi-square (df) | p | HIV+ N (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3511 (100) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity* | 87.2 (2) | 0.000 | |||

| Whites | 1019 (100) | 69 (7) | 1 | ||

| African-American | 581 (100) | 133 (23) | 4.1 (3.0-5.6) | ||

| Laino/Latina | 1807 (100) | 228 (13) | 2.0 (1.5-2.6) | ||

| Gender/MSM* | 44.7(2) | 0.000 | |||

| Non-MSM Males | 2714 (100) | 291 (11) | 1 | ||

| MSM | 168 (100) | 44 (26) | 3.0 (2.1-4.3) | ||

| Females | 623 (100) | 101 (16) | 1.6 (1.3-2.1) | ||

| Age* | 51.1 (1) | 0.000 | |||

| < 35 years of age | 553 (100) | 18 (3) | 1 | ||

| 35 or older | 2958 (100) | 420 (14) | 4.9 (3.0-8.0) | ||

| Drug Use Characteristics | |||||

| Daily injection* | 9.0 (1) | 0.003 | |||

| No | 797 (100) | 124 (16) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2713 (100) | 314 (12) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | ||

| Heroin injection* | 17.7 (1) | 0.000 | |||

| No | 254 (100) | 53 (21) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 3256 (100) | 385 (12) | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | ||

| Cocaine injection | 1.6 (1) | 0.206 | |||

| No | 2141 (100) | 255 (12) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1370 (100) | 183 (13) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | ||

| Speedball injection | 1.9 (1) | 0.172 | |||

| No | 1982 (100) | 234 (12) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1529 (100) | 204 (13) | 1.2 (0.9-1.4) |

Significant difference by chi-square test

Table 1b.

HIV serostatus by demographics and drug use characteristics among NIDU (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | Chi-square (df) | p | HIV+ N (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3543 (100) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity* | 22.6 (2) | 0.000 | |||

| Whites | 221 (100) | 10 (5) | 1 | ||

| African-American | 2277 (100) | 342 (15) | 3.7 (2.0-7.1) | ||

| Latino/Latina | 967 (100) | 113 (12) | 2.8 (1.4-5.4) | ||

| Gender/MSM* | 198.2 (2) | 0.000 | |||

| Non-MSM Males | 2542 (100) | 233 (9) | 1 | ||

| MSM | 220 (100) | 89 (40) | 6.7 (5.0-9.1) | ||

| Females | 774 (100) | 143 (18) | 2.3 (1.8-2.8) | ||

| Age* | 4.7 (1) | 0.031 | |||

| < 35 years of age | 390 (100) | 38 (10) | 1 | ||

| 35 or older | 3153 (100) | 431 (14) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | ||

| Drug Use Characteristics | |||||

| Heroin (nasal)* | 53.4 (1) | 0.000 | |||

| No | 1886 (100) | 323 (17) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1651 (100) | 145 (9) | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | ||

| Speedball (nasal) | 0.65 (1) | 0.422 | |||

| No | 3233 (100) | 433 (13) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 306 (100) | 36 (12) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | ||

| Cocaine (nasal)* | 14.4 (1) | 0.000 | |||

| No | 2072 (100) | 312(15) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1471 (100) | 157 (11) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | ||

| Smoked cocaine (crack)* | 56.5 (1) | 0.000 | |||

| No | 1139 (100) | 80 (7) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2403 (100) | 389 (16) | 2.6 (2.0-3.3) | ||

Significant difference by chi-square test

Previous testing for HIV

Large percentages of the PWID and NIDU participants reported that they had been tested for HIV prior to the HIV testing conducted as part of the study. Over the entire study period, 95% of PWID and 96% of NIDU reported previous testing for HIV. These percentages significantly increased during the study period (trend test z=6.63 among PWID, and 7.52 among NIDUs, p=0.000), with over 98% of both PWID and NIDU reporting previous HIV testing from 2008 on. (Full data available from the first author.)

Percentages of self-reported HIV seropositives on ART

Tables 2a and 2b show the percentages of PWID and NIDU who reported receiving ART in the 6 months prior to the interview among those who reported that they had tested positive for HIV. In contrast to the many differences in HIV prevalence (Tables 1a and 1b), there were relatively few differences in the percentages of HIV positive subjects who reported receiving ART. There were no differences by race/ethnicity. A slightly higher percentage of the MSM-PWID reported receiving ART, and a lower percentage of the female NIDU reported receiving ART. There were no differences in receiving ART by recent drug use behaviors among PWID or NIDU.

Table 2a.

Receiving ART by demographics and drug use characteristics among PWID reporting HIV seropositive status (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | Chi-square (df) | p | ART N (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 297 (100) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.15 (2) | 0.929 | |||

| Whites | 54 (100) | 29 (54) | 1 | ||

| African-American | 83 (100) | 42 (51) | 0.9 (0.4-1.8) | ||

| Laino/Latina | 150 (100) | 79 (53) | 1.0 (0.5-1.8) | ||

| Gender/MSM* | 6.1 (2) | 0.049 | |||

| Non-MSM Males | 189 (100) | 96 (51) | 1 | ||

| MSM | 35 (100) | 25 (71) | 2.4 (1.1-5.3) | ||

| Females | 70 (100) | 33 (47) | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | ||

| Age | 1.2 (1) | 0.284 | |||

| < 35 years of age | 11 (100) | 4 (36) | 1 | ||

| 35 or older | 284 (100) | 150 (53) | 2.0 (0.6-6.8) | ||

| Drug Use Characteristics | |||||

| Daily injection | 0.01 (1) | 0.928 | |||

| No | 97 (100) | 51 (53) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 198 (100) | 103 (52) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | ||

| Heroin injection | 2.4 (1) | 0.121 | |||

| No | 41 (100) | 26 (63) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 254 (100) | 128 (50) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | ||

| Cocaine Injection | 0.01 (1) | 0.920 | |||

| No | 162 (100) | 85 (52) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 133 (100) | 69 (52) | 1.0 (1.0-1.6) | ||

| Speedball injection | 1.3 (1) | 0.246 | |||

| No | 161 (100) | 89 (55) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 134 (100) | 65 (49) | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) |

Table 2b.

Receiving ART by demographics and drug use characteristics among NIDU reporting HIV seropositive status (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | Chi-square (df) | p | ART N (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 394 (100) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 1.4 (1) | 0.509 | |||

| Whites | 9 (100) | 5 (56) | 1 | ||

| African-American | 281 (100) | 183 (65) | 1.5 (0.4-5.7) | ||

| Latino/Latina | 98 (100) | 58 (59) | 1.2 (0.3-4.6) | ||

| Gender/MSM* | 9.2 (2) | 0.010 | |||

| Non-MSM Males | 185 (100) | 132 (71) | 1 | ||

| MSM | 79 (100) | 46 (58) | 0.6 (0.3-0.97) | ||

| Females | 124 (100) | 69 (56) | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | ||

| Age* | 5.6 (1) | 0.018 | |||

| < 35 years of age | 30 (100) | 13 (43) | 1 | ||

| 35 or older | 362 (100) | 235 (65) | 2.4 (1.1-5.1) | ||

| Drug Use Characteristics | |||||

| Heroin (nasal) | 0.4 (1) | 0.546 | |||

| No | 282 (100) | 181 (64) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 110 (100) | 67 (61) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | ||

| Speedball (nasal) | 1.2 (1) | 0.270 | |||

| No | 364 (100) | 233 (64) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 28 (100) | 15 (54) | 0.7 (0.3-1.4) | ||

| Cocaine (nasal) | 0.1 (1) | 0.738 | |||

| No | 260(100) | 166 (64) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 132 (100) | 82 (62) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | ||

| Smoked cocaine (crack) | 0.0 (1) | 0.967 | |||

| No | 63 (100) | 40 (63) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 329 (100) | 208 (63) | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) |

Significant difference by chi-square test

Trends in HIV prevalence and receiving ART

Tables 3a and 3b show the percentages of PWID and NIDU who tested HIV positive in the different years of the study, while tables 4a and 4b show the percentages of self-reported HIV positive PWID and NIDU who reported receiving ART (among those who reported that they had tested positive for HIV) in the different years of the study. HIV prevalence among both PWID and NIDU rose during the early 2000s, likely the result of increased provision of ART and the decrease in AIDS related deaths during this time [16]. Since the mid-2000s there has been a decline in HIV prevalence among both PWID and NIDU. The percentage of self-reported HIV seropositive PWID and NIDU who reported receiving ART in the 6 months prior to the interview increased significantly over the years, with 74% of PWID and 81% of NIDU reporting that they were on ART from 2012 to 2014.

Table 3a.

HIV seropositive percentages by year among PWID (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | HIV+ N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 3511 (100) | ||

| Year* | ||

| 2001 | 531 (100) | 72 (14) |

| 2002 | 535 (100) | 68 (13) |

| 2003 | 469 (100) | 51 (11) |

| 2004 | 186 (100) | 40 (22) |

| 2005 | 211 (100) | 35 (17) |

| 2006 | 236 (100) | 42 (18) |

| 2007 | 155 (100) | 32 (21) |

| 2008 | 151 (100) | 19 (13) |

| 2009 | 150 (100) | 19 (13) |

| 2010 | 131 (100) | 14 (11) |

| 2011 | 198 (100) | 17 (9) |

| 2012 | 245 (100) | 17 (7) |

| 2013 | 213 (100) | 6 (3) |

| 2014 | 100 (100) | 6 (6) |

Significant difference by trend test (z= −4.45, p=0.000)

Table 3b.

HIV seroprevalence by year among NIDU (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | HIV+ N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Year* | 3543 (100) | |

| 2001 | - | - |

| 2002 | 21 (100) | 2 (10) |

| 2003 | 241 (100) | 28 (12) |

| 2004 | 165 (100) | 24 (15) |

| 2005 | 314 (100) | 45 (14) |

| 2006 | 404 (100) | 77 (19) |

| 2007 | 383 (100) | 56 (15) |

| 2008 | 378 (100) | 65 (17) |

| 2009 | 321 (100) | 43 (13) |

| 2010 | 271 (100) | 41 (15) |

| 2011 | 280 (100) | 29 (10) |

| 2012 | 300 (100) | 28 (9) |

| 2013 | 270 (100) | 14 (5) |

| 2014 | 195 (100) | 17 (9) |

Significant difference by trend test (z= −4.18, p=0.000)

Table 4a.

Receiving ART by year of interview among PWID claiming HIV seropositive status (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | ART N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 297 (100) | ||

| Year* | ||

| 2001 | 42 (100) | 19 (45) |

| 2002 | 38 (100) | 13 (34) |

| 2003 | 24 (100) | 13 (54) |

| 2004 | 21 (100) | 8 (38) |

| 2005 | 22 (100) | 8 (36) |

| 2006 | 38 (100) | 19 (50) |

| 2007 | 28 (100) | 17 (61) |

| 2008 | 12 (100) | 4 (33) |

| 2009 | 15 (100) | 13 (87) |

| 2010 | 14 (100) | 9 (64) |

| 2011 | 14 (100) | 11 (79) |

| 2012 | 18 (100) | 12 (67) |

| 2013 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) |

| 2014 | 7 (100) | 6 (86) |

Significant difference by trend test (z= 4.14, p=0.000)

Table 4b.

Receiving ART by year of interview among NIDU reporting HIV seropositive status (2001-2014), New York City

| Total N (%) | ART N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 394 (100) | ||

| Year* | ||

| 2001 | - | - |

| 2002 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| 2003 | 16 (100) | 11 (69) |

| 2004 | 13 (100) | 7 (54) |

| 2005 | 31 (100) | 16 (52) |

| 2006 | 70 (100) | 33 (47) |

| 2007 | 46 (100) | 27 (59) |

| 2008 | 58 (100) | 39 (67) |

| 2009 | 39 (100) | 31 (79) |

| 2010 | 36 (100) | 23 (64) |

| 2011 | 28 (100) | 16 (57) |

| 2012 | 23 (100) | 19 (83) |

| 2013 | 13 (100) | 12 (92) |

| 2014 | 18 (100) | 13 (72) |

Significant difference by trend test (z= 3.07, p=0.002)

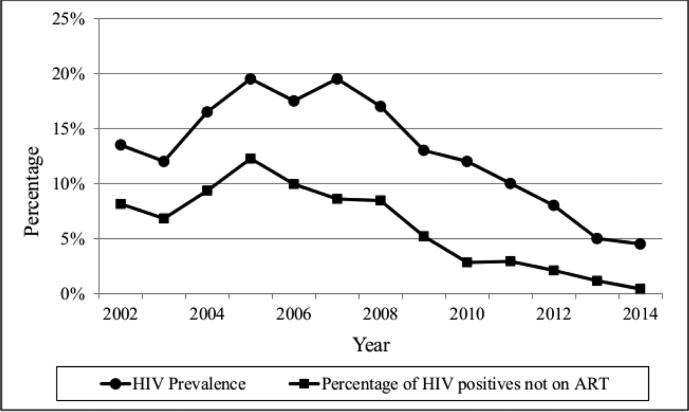

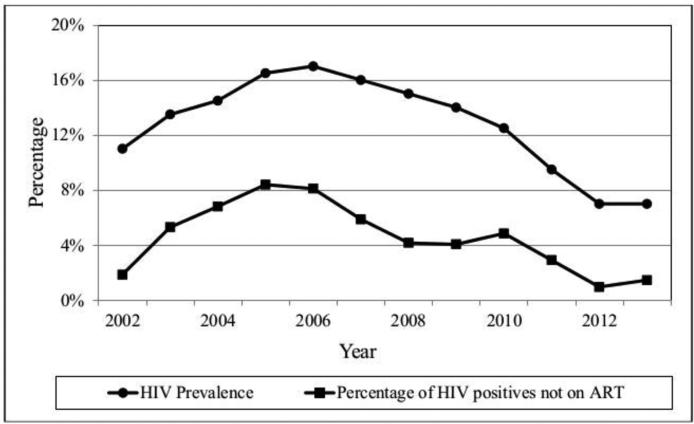

Figures 1a and 1b show HIV prevalence and the prevalence of persons who report that they are HIV positive and not on ART among PWID and NIDU during the study period. (Moving averages were used to smooth year-to-year variations.) HIV prevalence and the percentages of self-reported HIV positives not on ART have been decreasing since the mid-2000s.

Figure 1a.

HIV Prevalence and Percentage of HIV Positives not on ART among Persons who Inject Drugs

Figure 1b.

HIV Prevalence and Percentage of HIV Positives not on ART among Persons who Inject Drugs

We also conducted multivariable logistic regression to examine the association of demographic and drug use characteristics with reported receipt of ART. Three separate models were constructed. The first model assessed the associations among all participants. The second and third models were restricted, respectively, to PWID and NIDUs, in order to examine the specific drug use characteristics that are particular to each group. Backward elimination was used to arrive at the final version of each of the three models above. Year-of-interview, age (by year), gender, race/ethnicity, and injection status were included in all models. Injection drug use characteristics were additionally included in the PWID models. Non-injection drug use characteristics were additionally included in NIDU models. Table 5 shows the covariates that were significantly associated with receipt of ART. Year of injection and age were the variables most strongly associated with receiving ART. Year of injection presumably reflects changes in the New York City system of HIV testing, linkage to care and providing ART over time. Age presumably reflects the greater likelihood of developing symptoms and/or low CD4 cell counts among participants who had been infected with HIV for long periods of time. Interestingly, the only significant gender/MSM variable was that PWID participants who reported MSM behavior were slightly more likely to report receiving ART. Over 90% of our PWID reporting injecting heroin, so that we do not have a definitive explanation for the association between injecting heroin and not receiving ART other than PWID injecting other drugs but not heroin may be a small, special group.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic models of receiving ART among all participants, PWID, and NIDU (2001-2014)

| Variable | OR | z | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model: All Participants | |||||

| Year-of-interview | 1.14 | 3.74 | 0.000 | 1.06 | 1.22 |

| MSM | 1.60 | 1.92 | 0.055 | 0.99 | 2.58 |

| Female | 1.04 | 0.21 | 0.833 | 0.72 | 1.52 |

| Age | 1.04 | 3.26 | 0.001 | 1.02 | 1.07 |

| Model: PWID | |||||

| Year-of-interview | 1.18 | 2.76 | 0.006 | 1.05 | 1.33 |

| MSM | 5.62 | 2.93 | 0.003 | 1.77 | 17.86 |

| Female | 1.09 | 0.24 | 0.808 | 0.53 | 2.27 |

| Age | 1.06 | 2.65 | 0.008 | 1.02 | 1.11 |

| Heroin injection | 0.33 | −2.36 | 0.018 | 0.13 | 0.83 |

| Model: NIDU | |||||

| Year-of-interview | 1.11 | 2.52 | 0.012 | 1.02 | 1.21 |

| Age | 1.04 | 2.44 | 0.015 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

Discussion

We found that rates of HIV testing among PWID and NIDU were extremely high and have been so for over a decade. These findings are consistent with qualitative data from people who use drug who report ready access to, and frequent use of, HIV testing services [17]. In contrast to national data for all transmission groups where “not knowing one's status” represents a significant gap in the care continuum, HIV testing programs in New York City have been very effective in engaging PWID and NIDU in HIV testing.

During the past decade the proportion of HIV infected PWID and NIDU who report being on ART has increased significantly. Substance use has been cited by many researchers as representing a significant barrier to ART at the individual level [18,19], at the clinical provider level and at a range of social and structural levels [20]. While there is no doubt that real and significant barriers exist at each of these levels, our data show that, over the past decade, that there have been significant increases in the proportion of PWID and NIDU reporting taking ART. These improvements have occurred not only among those with a remote or past history of substance use but also among individuals with recent, severe drug use. The participants in this study were not only currently using substances (primarily heroin and cocaine), but were using at levels to where they were voluntarily entering substance use treatment. Despite these levels of drug use, a very high percentage—approximately three quarters over the last 3 years—reported that they were receiving ART. One inference from this is that there has been some reduction in individual, provider and system level barriers to active PWID and NIDU receiving ART. This finding also has potentially promising implications for providing HCV treatment to PWID [21].

The majority of subjects in this study were entering a short-term detoxification program. Short-term detoxification programs by themselves do not often produce long-term abstinence from illicit drugs; linkage to long-term treatment is generally needed to achieve long-term abstinence from illicit drugs. But short-term abstinence programs may be critical for stabilizing life situations and reducing drug use to levels where the participants are able to continue participating in and adhering to ART.

There are large racial/ethnic and gender disparities in HIV infection among people who use drugs in the US with African-Americans and Latino/as typically having twice the HIV prevalence of Whites, and females and MSM typically having twice the HIV prevalence of behaviorally heterosexual males [22,23]. The data on HIV prevalence among our participants (Tables 1a and 1b) illustrate this. We did not, however, find any racial/ethnic disparities and only modest gender disparities in receiving ART among our study participants (See Table 2a and 2b). This lack of disparities in the provision of ART is clearly a positive finding for public health. We would note, however, that it will be necessary to have greater percentages of racial/ethnic minorities, females and MSM on ART in order to overcome the disparities in HIV prevalence so that “treatment as prevention” is fully effective in all groups.

HIV prevalence initially increased among both PWID and NIDU in our study period. We believe that this was the result of the provision of ART leading to reductions in AIDS related death and disability among our participants [16]. HIV prevalence then declined to less than 10% by the end of the study period, and the percentage of HIV positive participants receiving ART increased from approximately 50% to approximately 75%. The percentages of PWID and NIDU who are HIV positive and not on ART are now well under 5%. This must be considered a very propitious indication of the prospects of “treatment as prevention” to contribute to an “AIDS free generation” for persons who use drugs in New York City. We do not have the detailed information needed to determine the causes of the trend for increased ART among our study participants, but it seems plausible that this trend is a result of improvements in the total system of HIV prevention and care for persons who use drugs in the New York City, including needle/syringe programs, substance use treatment programs, Ryan White supported programs, supported housing for HIV positives, efforts of providers to treat HIV infected persons who use drugs, efforts to link HIV positive persons to care, and increased support by the City and State health departments. Year of interview was a very strong predictor of being on ART among our participants, which suggest that the entire system did become more effective in placing people on ART over time.

We also do not have information on viral suppression among our HIV seropositive participants who reported being on ART. Over the time period for this study, the NYCDOHMH and New York City HIV treatment providers have increased efforts to place more HIV seropositive persons on ART and achieve sustained viral suppression among those on ART [24]. Thus, given the increasing rates of ART seen in this study, it is likely that the percentage of our HIV positive participants who are at viral suppression is likely to be increasing as well.

The NYCDOHMH does collect transmission risk category and laboratory testing data, including viral load results, for known HIV seropositive persons in New York City [25]. Among persons in the injecting drug use transmission category, 73 % of those known to be in care in 2012 (had a CD4 cell count, a CD4 percent, or a viral load assay in 2013) and 75% of those known to be in care in 2014 were at viral suppression (≤ 200 copies/ml) at their last viral load testing [25]. We thus estimated viral suppression among our PWID subjects for 2012-2014 using 98% tested for HIV (see HIV testing in Results section) 75% of those who self-reported as HIV were receiving ART (and thus were in care) times 74% of PWID in care are at viral suppression (average of 2012 and 2013 data from NYCDOHMH surveillance data cited above) = 0.98 × 0.75 × 0.74 = 54% at viral suppression. Given the similarities between the data for our PWID participants and our NIDU participants, we would also estimate that half or more of our NIDU subjects were at viral suppression for 2012-2014. Note that these estimates for our participants, all of whom had problematic drug use, are twice the CDC estimate of viral suppression among all HIV seropositives in the United States (25%) [6].

The simultaneous decreases in HIV prevalence (Tables 3a and 3b) and increases in HIV positive persons on ART (Tables 4a and 4b) may generate a positive feedback loop for reducing HIV incidence among persons who use drugs in New York City (Figures 1a and 1b). Fewer HIV seropositives and a higher percentage of HIV seropositives on ART should lead to less transmission of HIV. Less transmission would then lead to lower prevalence and then to even less transmission. It is not yet possible to determine the full extent to which HIV prevalence and incidence might be reduced, but a situation in which there are “very few” new HIV infections among persons who use heroin and cocaine appears to be an achievable public health goal for New York City [4]. We would caution, however, that it will be necessary to maintain HIV prevention and care programs. Travel to the city by HIV seropositive drug users from other areas and sexual transmission from persons who do not use drugs to drug users are likely to continuously re-introduce HIV infection into the New York City drug using population.

Limitations

Although the data reported here are from a single set of substance use programs in New York City, data from these programs have been fully consistent with data from other treatment programs and from community recruited samples in New York City [26,27].

As part of the informed consent process, participants are made aware that they may decline to answer any specific item in the questionnaire. A small percentage (approximately 2%) of subjects either declined to answer the question on whether they had ever received a positive HIV test result, or gave answers that appeared to be biased by social desirability, e.g., they reported testing HIV negative when our study testing showed them to be HIV positive. Persons who did not report that they had received an HIV positive test result were not asked questions about receiving ART. We are conducting a separate analysis of these participants. The numbers of such participants were sufficiently small and are declining over time, so that it is extremely unlikely that they would influence the results of the analyses presented here.

We did not measure adherence in this study, as it would have been necessary to measure for multiple time periods (very recent through months prior to interview) and multiple measures would probably have been needed. Adherence may have been particularly difficult in the period of intense drug use prior to entering drug treatment and in the transition from living in the community to an inpatient setting. We are now adding measures of adherence to the continuing study.

The participants in this study were primarily using heroin and/or cocaine; very few reported methamphetamine use (less than 1% of our sample). We did not find any significant differences in receiving ART by patterns of recent drug use, but generalization of our results to persons with primary methamphetamine use should be done with great caution.

Conclusions

There are many potential difficulties in providing ART to persons with problematic substance use. These difficulties may occur in all stages along the continuum of HIV care. Despite these difficulties, New York City has been making considerable progress in providing ART to both persons who inject drugs and non-injecting drug users. As an addition to the other elements of “combined prevention” (needle/syringe programs, substance use treatment) it would appear that “Ending the Epidemic” [28] and achieving an “AIDS-free generation”— could be reached within the near future for persons who use heroin and cocaine in New York City.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported through funding grants 5RO1DA003574 and 1R01DA0356707-01 from the National Institutes of Health. We would also like to thank Sarah Braunstein and Laura Karasankse of NYC Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene for providing information on viral suppression. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organizations or the agencies the authors are affiliated with.

References

- 1.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adolescent Adults Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009:1–161. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farley T. Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. NYC Health; Queens: 2011. 2011 Advisory #27: Health Department Releases New HIV Treatment Recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartcollis A. Cuomo Plan Seeks to End New York's AIDS Epidemic. New York Times. 2014 Jun 28;:A18. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinton H. Creating an AIDS-free generation [Internet] Department of State; Washington (DC): Nov 8, 2011. [2012 Jun 5]. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS UNAIDS 2011-2015 Strategy Getting Close to Zero: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2014.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC Fact Sheet: HIV in the United States: The Stages of Care. CDC; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucas GM. Substance abuse, adherence with antiretroviral therapy, and clinical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Life Sci. 2011 May 23;88(21-22):948–952. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombard F, Proescholdbell RJ, Cooper K, Musselwhite L, Quinlivan EB. Adaptations across clinical sites of an integrated treatment model for persons with HIV and substance abuse. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009 Aug;23(8):631–638. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tetrault JM, Moore BA, Barry DT, et al. Brief versus extended counseling along with buprenorphine/naloxone for HIV-infected opioid dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012 Dec;43(4):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walley AY, Tetrault JM, Friedmann PD. Integration of substance use treatment and medical care: a special issue of JSAT. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012 Dec;43(4):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Friedman SR. HIV among drug users at Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City, the first 25 years. Subst Use Misuse. 46(2-3):131–139. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene . HIV Surveillance & Epidemiology Program - HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. NYCDOHMH; New York City: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Novick DM, et al. HIV-1 infection among intravenous drug users in Manhattan, New York City, from 1977 through 1987. JAMA. 1989;261:1008–1012. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.7.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Des Jarlais D, Arasteh A, Hagan H, McKnight C, Perlman D, Friedman S. Persistence and change in disparities in HIV infection among injecting drug users in New York City after large-scale syringe exchange. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S445–S451. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.159327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stata 12 [computer program] College Station, Texas: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene . HIV Surveillance & Epidemiology Program - HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics. NYCDOHMH; New York City: 1982-2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan AE, Masson CL, Mateu-Gelabert P, et al. Perceptions of drug users regarding hepatitis C screening and care: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, et al. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):756–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharpe TT, Lee LM, Nakashima AK, Elam-Evans LD, Fleming PL. Crack cocaine use and adherence to antiretroviral treatment among HIV-infected black women. J Community Health. 2004;29(2):117–127. doi: 10.1023/b:johe.0000016716.99847.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coetzee B, Kagee A, Vermeulen N. Structural barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a resource-constrained setting: the perspectives of health care providers. AIDS Care. 23(2):146–151. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perlman DC, Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer J. Can HIV and HCV Infection be Eliminated among Persons who Inject Drugs? J Addict Dis. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2015.1059111. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, McKnight C, Perlman DC, Cooper HL, Hagan H. HSV-2 Infection as a Cause of Female/Male and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Infection. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer JP, Modi SN, Arasteh K, Hagan H. Are females who inject drugs at higher risk for HIV infection than males who inject drugs: an international systematic review of high seroprevalence areas. Drug Alcohol Depend. 124(1):95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irvine MK, Chamberlin SA, Robbins RS, et al. Improvements in HIV care engagement and viral load suppression following enrollment in a comprehensive HIV care coordination program. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu783. ciu783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene . HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013. NYCDOHMH; New York City: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Des Jarlais DC, Perlis T, Friedman SR, et al. Declining seroprevalence in a very large HIV epidemic: injecting drug users in New York City, 1991 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(12):1801–1806. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Perlis T, et al. Convergence of HIV seroprevalence among injecting and non-injecting drug users in New York City. AIDS. 2007;21(2):231–235. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280114a15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New York State Department of Health . Ending the Epidemic Task Force. NYSDOH; Albany: 2014. [Google Scholar]