Summary

Heart failure is characterized by the transition from an initial compensatory response to decompensation, which can be partially mimicked by transverse aortic constriction (TAC) in rodent models. Numerous signaling molecules have been shown to be part of the compensatory program, but relatively little is known about the transition to decompensation that leads to heart failure. Here we show that TAC potently decreases the RBFox2 protein in the mouse heart, and cardiac ablation of this critical splicing regulator generates many phenotypes resembling those associated with decompensation in the failing heart. Global analysis reveals that RBFox2 regulates splicing of many genes implicated in heart function and disease. A subset of these genes undergoes developmental regulation during postnatal heart remodeling, which is reversed in TAC-treated and RBFox2 knockout mice. These findings suggest that RBFox2 may be a critical stress sensor during pressure overloading-induced heart failure.

Introduction

The mammalian heart contains post-mitotic cardiomyocytes, and pathological loss of these cells is the ultimate cause of heart failure (Diwan and Dorn, 2007). Most forms of cardiomyopathy are associated with initial cardiac hypertrophy, which has been widely considered a compensatory program during pathological conditions. However, hypertrophy per se is not a prerequisite for heart failure, as it also occurs under physiological conditions (e.g. exercise). Even under pathological conditions (i.e. hypertension, myocardial infarction or ischemia), hypertrophy can be decoupled from functional compensation in various genetic models (Hill et al., 2000). Instead, progression to heart failure is linked to the so-called decompensation process, which leads to myocardial insufficiency (Diwan and Dorn, 2007). The induction of several critical signaling pathways has been linked to the compensatory program, some of which appear to also contribute to decompensation (Marber et al., 2011). However, relatively little is known about molecular events responsible for the transition from compensation to decompensation. In fact, global approaches have been applied to heart disease samples from both humans and animals (Giudice et al., 2014; Kaynak et al., 2003), but it remains unclear whether dysregulation of individual genes are a cause or consequence of heart failure.

The RBFox family of RNA binding proteins has been implicated in development and disease (Kuroyanagi, 2009). Mammalian genomes encode three RBFox family members, all of which show prevalent expression in the brain. RBFox1 (A2BP1) and RBFox2 (RMB9 or Fxh) are known to play central roles in brain development (Gehman et al., 2012; Gehman et al., 2011), whereas RBFox3 (NeuN) is a well-established biomarker for mature neurons (Kim et al., 2009). In addition, both RBFox1 and RBFox2 are expressed in the heart where RBFox2 is expressed from embryo to adult and RBFox1 is induced in postnatal heart (Kalsotra et al., 2008), contributing to heart development and function in zebrafish (Gallagher et al., 2011). Up-regulation of RBFox1 has been detected in the failing heart in humans (Kaynak et al., 2003), whereas mutations in RBFox2 have been linked to various human diseases, including autism (Sebat et al., 2007) and cancer (Venables et al., 2009). A more recent study demonstrated that RBFox2, but not RBFox1, is required for myoblast fusion during C2C12 cell differentiation (Singh et al., 2014), thus strongly implicating RBFox2 in heart development and function in mammals. At the molecular level, both RBFox1 and RBFox2 have been extensively characterized as splicing regulators that recognize the evolutionarily conserved UGCAUG motif in pre-mRNAs (Zhang et al., 2008) and regulate alternative splicing in a position-dependent manner (Yeo et al., 2009).

In the present study, we report that the RBFox2 protein is decreased in response to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) in the mouse heart, and cardiac-specific ablation of RBFox2 generates an array of phenotypes resembling those in TAC-induced heart failure. Global analysis reveals an extensive RBFox2-regulated splicing program, which likely constitutes a key part of the developmental program during postnatal heart remodeling, and importantly, both TAC treatment and RBFox2 ablation reverse this splicing program. These findings suggest that diminished RRFox2 expression may be a key event during heart decompensation.

Results

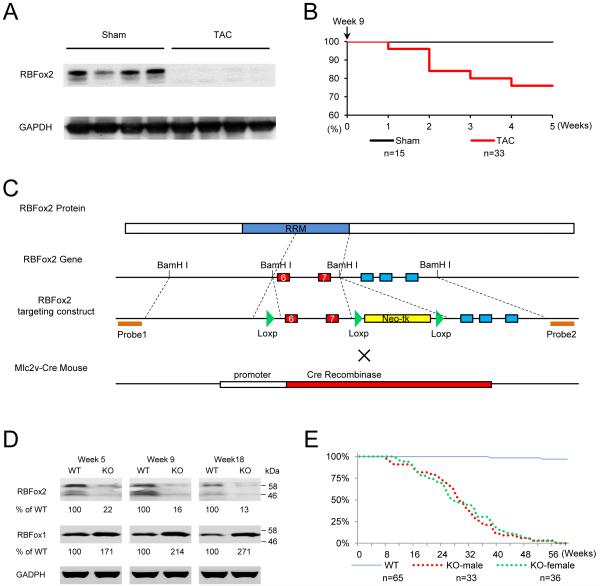

RBFox2 is functionally linked to to pressure overloading-induced heart failure

RBFox2 shows prevalent expression throughout heart development (Kalsotra et al., 2008), but its biological function in cardiac muscle and potential contribution to heart disease in mammals has remained unexplored. We first tested whether RBFox2 expression might be perturbed in a TAC-induced heart failure model. Strikingly, we found that RBfox2 protein was largely diminished in the heart of live mice five weeks after TAC (Figure 1A), which resulted in ~30% mortality (Figure 1B). These data suggests that RBFox2 may function as a key sensor to cardiac stress and its down-regulation is linked to heart failure.

Figure 1. Essential requirement for RBFox2 to prevent heart failure.

(A) Western blotting analysis of RBFox2 in sham- and TAC-treated mice after 5 weeks of surgery. GADPH served as a loading control.

(B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of sham and TAC littermate male mice.

(C) Diagram of conditional RBFox2 knockout and generation of heart-specific knockout by crossing with an Mlc2v-Cre transgenic mouse.

(D) Western blotting analysis of RBFox1 and RBFox2 in wild-type (WT) and RBFox2 knockout (KO) cardiomyocytes at three postnatal stages. Triplicate results were quantified relative to WT, as indicated below each gel.

(E) Survival curves of WT and RBFox2 KO littermate mice in both sexes.

To determine whether RBFox2 has a potential to contribute to, rather than as a functional consequence of, heart failure, we took advantage of an RBFox2 conditional knockout mouse (Gehman et al., 2012). By crossing RBFox2f/f mice with an Mlc2v-Cre (active at E8.5) transgenic mouse (Chen et al., 1998), we ablated the gene at the onset of cardiogenesis (Figure 1C). Mice with different genotypes all gave live birth, indicating that, once the cardiogenic program is lunched, RBFox2 is not essential for the remaining steps in organ formation throughout embryonic development.

Western blotting showed that the RBFox2 protein was substantially reduced in isolated RBFox2−/− cardiomyocytes at several postnatal stages we examined (Figure 1D). In comparison, RBFox1 was elevated to some extent in RBFox2−/− hearts, indicating a degree of functional compensation. However, RBFox2 clearly has a unique functional requirement in the heart, as less than 5% of RBFox2-ablated mice of both sexes were able to survive beyond one year (Figure 1E). These results establish an essential function of RBFox2 in postnatal heart, and importantly, suggest that diminished RBFox2 may be functionally linked to pressure overloading-induced heart failure.

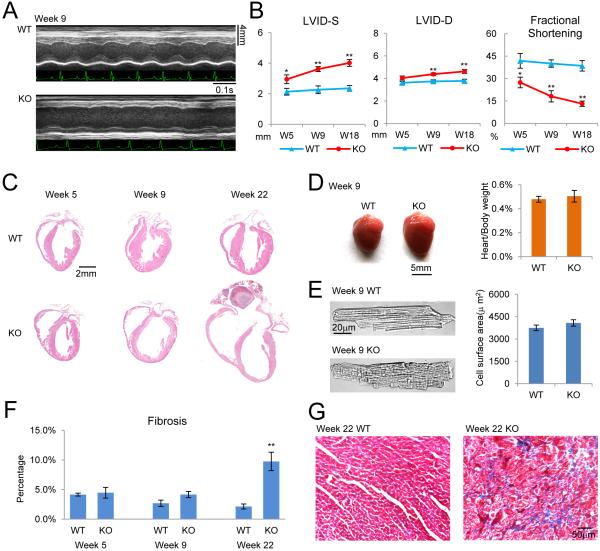

RBFox2 ablation causes dilated cardiomyopathy that leads to heart failure

By echocardiography, we recorded severe contraction defects in RBFox2−/− heart (Figure 2A and S1A), which is characterized by a significant increase in both end-systolic and end-diastolic Left Ventricular Internal Dimension (LVID-S and LVID-D), resulting in progressive decrease in fractional shortening with age (Figure 2B and S1A). At week 5, both the gross morphology and structure of the RBFox2−/− heart showed relatively minor defects (Figure 2C and S1B), but by 9 weeks, the cardiac chamber began to enlarge and the ventricular wall became thinner, and by 22 weeks, the RBFox2−/− heart developed typical dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (Figure 2C). Intriguingly, the development of DCM in RBFox2−/− mice was not accompanied by advent of cardiac hypertrophy, as indicated by similar heart/body ratio to WT mice (Figure 2D) and by little increase in cell surface area of cardiomyocytes isolated by enzymatic perfusion at week 9 (Figure 2E). These observations imply that dysregulated RBFox2 may selectively contribute to heart decompensation without first inducing hypertrophy. H&E (Hematoxylin and Eosin) staining showed extensive disconnection of cardiomyocytes and Trichrome staining and revealed increased fibrosis at week 9 and onward (Figure S1B, 2F and 2G).

Figure 2. General heart failure phenotype induced in RBFox2 ko mice.

(A) Examples of cardiac echocardiography of WT and RBFox2 KO mice acquired at 9 weeks of age.

(B) Key echocardiography parameters of WT and RBFox2 KO mice at different ages. LVID-D: left ventricular internal dimension values at end-diastole; LVID-S: left ventricular internal dimension values at end-systole. The data in each group were collected from 5 to 8 mice and expressed as mean±SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01.

(C) H&E staining of the coronal sections of WT and RBFox2 KO hearts at different ages.

(D) Size and mass of WT and RBFox2 KO hearts at 9 weeks of age. Left panel: Side by side comparison between WT and KO hearts at 9 weeks. Right panel: Statistics of the heart-to-body weight ratio of WT and KO hearts. The data in each group were collected from 3 mice and expressed as mean±SEM.

(E) Size of cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and RBFox2 KO hearts at 9 weeks of age. Left panel: Transmission images of WT and RBFox2-deleted cardiomyocytes. Right panel: Statistics of the cell surface area of WT and KO cardiomyocytes. The data in each group were based on analysis of 23 to 25 cells from 3 mouse hearts and expressed as mean±SEM.

(F) Statistics of fibrosis from Trichrome-stained WT or RBFox2 KO hearts at different development stages. The data in each group were based on analysis of 5 to 6 images from 2 mice and expressed as mean±SEM. **P <0.01.

(G) Trichrome staining for fibrosis and myofibril disorder in RBFox2 KO heart by 22 weeks. See also Figure S1.

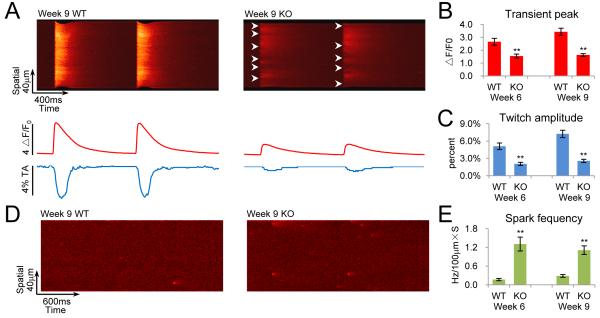

We next examined calcium-handling properties on isolated RBFox2−/− cardiomyocytes. High-resolution line-scan mode confocal microcopy revealed weakened calcium transients (Figure 3A and 3B), resulting in impaired whole cell twitch (Figure 3C), even though the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) content remained unaltered (Figure S2A). The calcium-handling defect was also reflected by a significant elevation of self-evoked calcium sparks (Figure 3D and 3E), indicative of severe calcium leak (Cheng and Lederer, 2008). To further establish the primary effects, we used two independent siRNAs to knock down RBFox2 on cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes from WT mice (Figure S2B), and observed similar calcium handling defects (Figure S2C), including reduced transient peak (Figure S2D), increased calcium sparks (Figure S2E), and elevated spontaneous transient frequency (Figure S2F). These results suggest a direct contribution of RBFox2 to excitation-contraction (EC) coupling in cardiac muscle.

Figure 3. Defective EC coupling in RBFox2 knockout cardiac muscle.

(A) Confocal images of intracellular calcium transients and contraction. Isolated cardiomyocytes from WT and KO mice at 9 weeks of age were paced electrically at 1.0 Hz. Lower panels show the traces of spatially averaged calcium transient (top) and the corresponding cell shortening (bottom).

(B and C) Statistics of calcium transient peak (ΔF/F0, which is defined as the ratio between the signal and baseline) and twitch amplitude (TA) in cardiomyocytes from WT and KO mice at two different ages. The data were based on analysis of 13 to 20 cells from three hearts and expressed as mean±SEM. **P <0.01.

(D) Confocal measurement of spontaneous calcium sparks in 9 weeks WT or KO cardiomyocytes at rest.

(E) Statistics of the frequency of calcium sparks in cardiomyocytes from WT or KO mice at two different ages. The data were based on analysis of 14 to 20 cells from three hearts and expressed as mean±SEM. **P <0.01. See also Figure S2 on the results observed on RBFox2 siRNA-treated cardiomyocytes.

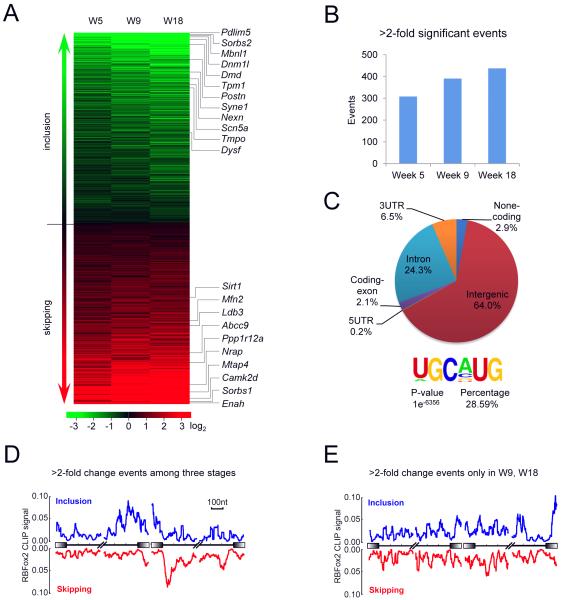

RBFox2 regulates a large splicing program in cardiac muscle

As RBFox2 is a well-established splicing regulator, we next aimed to elucidate the mechanism underlying the observed functional defects by profiling the splicing program perturbed in RBFox2−/− heart. We took advantage of the RNA annealing-selection-ligation coupled with deep sequencing (RASL-seq) platform developed in our lab (Zhou et al., 2012), which measures 3884 annotated alternative splicing events in the mouse genome, thus providing a sensitive and cost-effective mean to broadly survey RBFox2-regulated splicing. To distinguish between likely direct functional consequences and those additionally altered by accumulating defects, we surveyed three specific developmental stages at postnatal week 5, 9, and 18 in triplicate (Figure 4A and S3A), which respectively represents an initial stage that showed detectable but minimal pathology, an intermediate stage associated with evident cardiac malfunction, and a late stage when knockout mice began to die (see Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 4. Primary and accumulated defects in disease progression.

(A) The heatmap of the splicing profiling data by RASL-seq among three different disease stages. The data were sorted by the mean value of the three stages groups analyzed. Green: induced inclusion; red: induced skipping. Genes that were previously linked to dilated cardiomyopathy are highlighted on the right.

(B) Number of > 2-fold significant events among disease stages.

(C) The genomic distribution of RBFox2 CLIP-seq reads. The top enriched motif and the percentage of the motif on total CLIP peaks are shown on the lower panel.

(D and E) The RNA maps of RBFox2 binding and splicing responses based on those with >2-fold change relative to WT consistently detected among all three stages.

(D) versus changes detected only in mice of week 9 and 18 (E). See also Figure S3 and Table S2.

We recorded a sufficient number of splicing changes (>10 counts with both isoforms, p<0.05 among triplicate) among ~70% of total surveyed splicing events in both WT and RBFox2−/− hearts at all three stages (Figure S3B). In aggregate, we detected a total of 709 splicing switching events in 624 genes, among which 346 events exhibited enhanced exon skipping and 363 events displayed induced exon inclusion in response to RBFox2 ablation (Figure 4A and Table S2). We noted that the number of dysregulated splicing events is already comparable to that identified by large-scale RNA-seq on RBFox2 siRNA-treated C2C12 cells (Singh et al., 2014), even though our platform only surveys a set of annotated splicing events. Interestingly, the number of altered splicing events increased during DCM progression: Using a stringent cutoff (>2-fold in ratio change in addition to p<0.05), we identified 308 (43.4% of total), 390 (55.0%) and 437 (61.6%) altered splicing events at week 5, 9, and 18, respectively (Figure 4B, S3A and Table S2). Together, these findings reveal an extensive splicing program regulated by RBFox2 in the mouse heart.

Context-dependent RBFox2 binding is responsible for early induced splicing events

The splicing changes detected at week 5 are likely direct targets because of minimal morphological and structural changes detected at this stage. One effective way to identify direct RBFox2 targets is to determine RBFox2 binding events on induced alternative splicing events and link RBFox2 binding to functional consequences based on its well-established position-dependent effects. We therefore performed genome-wide analysis of RBFox2-RNA interactions by crosslinking iummunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (CLIP-seq) on primary cardiomyocytes isolated from WT mice. From 67 million mapped reads and after removing PCR products based on built-in barcodes, we obtained ~15 million CLIP-seq reads that were uniquely mapped to the mouse genome (Figure S3C). Interestingly, 64.0% reads were mapped to intergenic regions, indicating additional functions of RBFox2 in the mouse genome, and 24.3% reads to intron regions, consistent with its roles in regulated splicing (Figure 4C). The RBFox2 CLIP-seq reads were enriched with the expected UGCAUG motif (Figure 4C and S3D), which underlies ~29% of 149,832 identified RBFox2 binding peaks (Figure 4C), similar to our previous observation on ES cells (Yeo et al., 2009).

We next linked the CLIP-seq data to regulated splicing events detected by RASL-seq, observing the expected positional effects on significantly altered events detected at all three stages, showing enhanced exon inclusion when RBFox2 bound upstream introns and stimulated exon skipping when RBFox2 bound downstream introns (Figure 4D). In contrast, we saw no such correlation with the splicing responses additionally detected at weak 9 and 18 (Figure 4E). These data indicate that the alternatively spliced genes recorded at week 5 are likely primary targets for RBFox2 whereas those additionally detected in later stages are secondary responses to accumulating defects in RBFox2−/− heart.

Critical splicing changes underlie specific functional defects in RBFox2 knockout mice

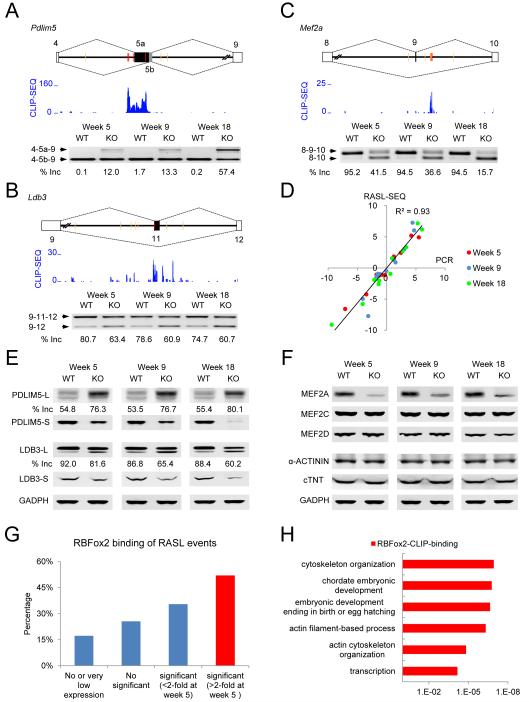

We previously demonstrated the robustness of the RASL-seq platform in profiling alternative splicing (Zhou et al., 2012), which we further confirmed by RT-PCR on a panel of altered splicing events at three developmental ages and linked those induced splicing to specific RBFox2 binding events (Figure 5A-5D and S4). Specific genes chosen for validation were based on their existing functional information on heart development and/or disease. For example, Pdlim5 and Ldb3 are important for maintaining the structural integrity of the contractile apparatus in the heart (Cheng et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2009). RBFox2 bound multiple strong consensus motifs (red) located in the upstream intronic regions as well as on the alternative Pdlim5 exon 5a, resulting in suppression of the alternative exon (Figure 5A). Near the alternative exon 11 in Ldb3, RBFox2 bound both upstream and downstream intronic regions (although these motifs were not evolutionarily conserved, labeled yellow, indicating potential synergistic actions of other RNA binding proteins) with a net effect that led to exon skipping in RBFox2−/− heart (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Critical splicing changes linked to specific defects in the contractile apparatus.

(A) Induced exon inclusion in Pdlim5. Top: The gene structure, illustrating the alternative exon 5a and 5b. Yellow and red lines indicate the locations of non-conserved and conserved (U)GCAUG motifs, respectively. Middle: The RBFox2 CLIP-seq signals. Bottom: the RT-PCR results and calculated percentages of Splice-In (included exon divided by both isoforms) in each sample.

(B) Induced exon skipping in Ldb3. The gene structure, motif distribution, and CLIP-seq signals were similarly annotated as in A.

(C) Induced exon skipping in Mef2a. The gene structure, motif distribution, and CLIP-seq signals were similarly annotated as in A.

(D) PCR validation of 11 RASL events at three different disease stages. Black line shows the correlation of all 33 PCR results.

(E) Western blotting analysis of PDLIM5 and LDB3 in WT and KO cardiomyocytes. Note that both PDLIM5 and LDB3 have long and short isoforms resulting from alternative polyadenylation. In both cases, the long isoform contains the alternatively spliced products. The percentages of exon inclusion based on the intensity of protein isoforms on the gel. The results had been repeated on different sets of WT and KO hearts.

(F) Western blotting analysis of multiple MEF2 family proteins. α-ACTININ and c-TNT served as loading controls.

(G) Percentage of directly RBFox2 binding events in different RASL-seq data groups.

(H) Gene ontology analysis of direct RBFox2 target genes in biological processes based on the DAVID database. See also Figure S4.

We further probed the protein levels by Western blotting, showing reciprocal increase in the exon 5a-containing L isoform and decrease in the exon 5b-containing S isoform in the case of Pdlim5 in response to RBFox2 knockout (Figure 5E). Note that both Pdlim5 and Ldb3 genes produced two alternatively polyadenylated isoforms (L and S) in which the L isoform carried both alternatively spliced mRNA isoforms, and RBFox2 ablation induced the smaller isoform at both the RNA and protein levels (Figure 5B and 5E). The protein levels of both PDLIM5-S and LDB3-S were also progressively diminished, indicating accumulating effects in RBFox2−/− heart (Figure 5E).

We similarly validated additional RBFox2-regulated genes at week 5 and onward, including Abcc9 (an ATP-sensitive potassium channel), Sorbs1 and Sorbs2 (both being SH3 domain-containing signaling molecules) and Enah (involved in cytoskeleton organization and remodeling), each of which showed specific RBFox2 binding events at locations that are consistent with the positional rule established for RBFox2-regulated splicing (Figure S4). Importantly, these genes have also been previously linked to dilated cardiomyopathy (Aguilar et al., 2011; Bienengraeber et al., 2004; Gehmlich et al., 2007; Yung et al., 2004).

Critical splicing events were induced in key transcription factor genes

We also observed a major impact of RBFox2 ablation on alternative splicing of the MEF family of transcription factors, causing the exclusion of the alternative exon 9 in Mef2a and the alternative exon 7’ in Mef2d (Figure 5C and S4), similar to a recent report in C2C12 cells (Singh et al., 2014). These induced isoform switches have been previously shown to affect their activities in transcription (Zhu et al., 2005), consistent with widespread changes at gene expression levels in RBFox2 siRNA-treated C2C12 cells (Singh et al., 2014). Interestingly, while the alternative exon does not change the reading frame in both of these cases, we additionally detected a major reduction of Mef2a protein (Figure 5F), indicating the involvement of RBFox2 in additional layers of regulation. The altered transcription program may thus account for accumulating changes in alternative splicing during the development of disease phenotype in RBFox2−/− heart, as suggested for the function of RBFox1 in the nervous system (Fogel et al., 2012).

From the global prospective, we found that RBFox2 binding events are directly linked to induced alternative splicing events at week 5 (Figure 5G). Importantly, via GO term analysis of all expressed genes detected by RNA-seq (data not shown) in the mouse heart at the same developmental stage, we found that direct RBFox2 target genes are enriched in cytoskeleton organization and transcription in biological processes (Figure 5H). Together, these observations suggest that the RBFox2-regulated splicing program may directly contribute to the development of disease phenotype in RBFox2−/− heart and many secondary effects, especially those observed in late stages, may result from induced splicing of key genes involved in transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls in cardiac muscle.

Pressure overloading and RBFox2 ablation induce a related splicing program

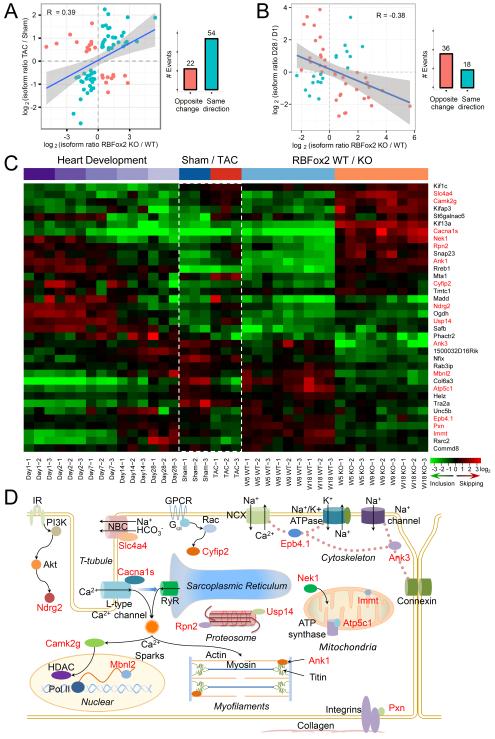

Because TAC-induced pressure overloading diminished RBFox2, we next performed RASL-seq on sham and TAC-treated hearts, identifying 199 significantly changes splicing events (Figure S5A and Table S3). These data allowed us to compare with the splicing program in RBFox2−/− heart despite the fact that the altered splicing events in TAC-treated hearts were measured on mice at age 14 (TAC treatment began at week 9 and lasted for 5 weeks), while total RNAs were extracted from RBFox2 knockout mice at postnatal week 5 after deletion of the gene in an early embryonic stage. We thus anticipated numerous compound effects to generate unique spectra of splicing changes on the two different animal models. Nonetheless, comparing between 709 splicing switches in RBFox2−/− heart and 199 events in response to TAC surgery in adult mice, we identified 76 shared events that show an overall positive correlation between the two experimental conditions (Figure 6A, left panel; Table S3). Importantly, among these 76 overlapping events, 54 (71%) showed changes in the same directions (Figure 6A, right panel). Thus, diminished RBFox2 expression appears to partially contribute to TAC-induced splicing and heart failure.

Figure 6. RBFox2 ablation induce alternative splicing events in the opposite directions during heart remodeling.

(A) Positive correlation between significantly changed splicing events detected response to RBFox2 KO and TAC surgery. Green-colored dots show changes in the same directions; Orange-colored dots indicate changes in the opposite directions, as summarized in the right panel.

(B) Negative correlation between 54 events commonly induced by RBFox2 KO and TAC and those detected during postnatal heart modeling from day 1 to day 28. Green-colored dots show changes in the same directions; Orange-colored dots indicate changes in the opposite directions.

(C) Heatmap of 36 regulated splicing events that show opposite changes during heart remodeling relative to RBFox2 KO and TAC surgery. Red-labeled on the right are genes previously implicated in heart function and/or disease.

(D) Diagram that highlights 15 genes (from red-labeled ones in C) with diverse regulatory functions in cardiomyocyte. IR: insulin receptor. See also Figure S5 and Table S3.

Heart modeling-induced splicing events are reversed in failing heart

While the identified alternative splicing events in RBFox2−/− or in TAC-treated hearts provide a rich resource for functional dissection on the single gene basis to understand the contribution of individual altered splicing events to specific cardiac functions, the induced splicing program as a whole is likely responsible for the complex heart failure phenotype observed on each animal model. One way to assess the global contribution of RBFox2-regulated splicing to heart failure is to compare the compendium of RBFox2 ablation- or TAC-induced splicing events with the splicing program associated with postnatal heart remodeling. This developmentally regulated process occurs in the first month of newborn mice, critical for enhancing cardiac performance to meet the demand for increasing workload. In fact, multiple reprogramming events have been characterized at the level of transcription, such as switches in the expression of α to β myosine heavy chain, fetal to adult troponin I , and β to α-tropomyosin (Muthuchamy et al., 1993). Importantly, switches of these genes in the reverse direction are often associated with heart failure (Krenz and Robbins, 2004; Muthuchamy et al., 1998). We thus hypothesized that the splicing program might also undergo critical reprogramming during heart remodeling.

To test this hypothesis, we performed RASL-seq on 5 developmental points in the first month of newborn mice from day 1 to day 28. Comparison between the two end points revealed 564 significant switches in alternative splicing (Figure S5B), consistent with the previous report (Giudice et al., 2014), indicating that heart remodeling in the mouse is also associated with extensive reprogramming at regulated splicing levels, which may collectively contribute to augmented heart performance. Focusing on the 54 genes that showed significantly altered splicing in the same directions between RBFox2−/− and TAC-treated hearts (Figure 6A), we found an overall negative correlation between development-associated changes and those induced by RBFox2 ablation (Figure 6B, left panel; Table S3). Among these events, 36 (67%) showed changes in opposite directions (Figure 6B, right panel), indicating a substantial contribution of RBFox2-controled splicing to heart remodeling.

Developmentally regulated RBFox2 target genes provide diverse cardiac functions

To better appreciate the developmentally regulated splicing program relative to TAC-induced and RBFox2 ablation-triggered splicing events, we displayed dynamic splicing changes in the 36 genes surveyed by RASL-seq at different developmental stages or under various treatment conditions (Figure 6C, green or red colors highlight induced inclusion or skipping of alternative exons). We noted that the patterns are similar between mice at day 28 and sham-operated mice at week 14, indicating that those developmentally regulated splicing events had largely completed after postnatal remodeling in the first month and the induced mRNA isoforms then remain relatively constant in the adulthood. In contrast, a large percentage of these developmentally reprogrammed splicing events were reversed in response to TAC treatment or RBFox2 ablation (Figure 6C). This reversal strongly suggests that RBFox2-regulated splicing events contribute to augmented heart performance in adult mice.

Importantly, the majority of those developmentally regulated RBFox2 target genes (red-labeled genes on the right side of Figure 6C) have been previously implicated in heart function and/or disease. Among these genes, two (Epb4.1, which encodes for protein 4.1R, and Atp5c1, which encodes for the ATP synthetase γ subunit F1γ) have been extensively characterized as direct targets for the RBFox family of splicing regulators and RBFox-mediated repression of the alternative exon in each case has been shown to be critical for enhanced cardiac function (Hayakawa et al., 2002; Ponthier et al., 2006). Our data now indicate that these genes are also developmentally repressed during postnatal modeling, which becomes derepressed in response to both TAC treatment and RBFox2 ablation. Two other genes (Camk2γ and Slc4a4) have also been reported to respond to pressure overloading in the heart (Colomer et al., 2003; Yamamoto et al., 2007).

Other genes that show strong developmental regulation and reversal in TAC-treated and RBFox2 ablated mice include those involved in (1) cytoskeleton organization: Ank1 (Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos and Bloch, 2003) and Ank3 (Sato et al., 2011), (2) Ca++ handling: Epb4.1 (Stagg et al., 2008) and Camk2γ (Kwiatkowski and McGill, 2000), (3) regulation of channel activities: Slc4a4 (Yamamoto et al., 2007) and Cacna1s (Stunnenberg et al., 2014), (4) proteasome functions: Usp14 (Wilson et al., 2002) and Rpn2 (Rosenzweig et al., 2012), (5) cellular signaling: Pxn (Melendez et al., 2004), Nek1 (Chen et al., 2009), and Cyfip2 (Schenck et al., 2003), (6) mitochondrial activities: Immt (Yang et al., 2012) and Atp5c1 (Hayakawa et al., 2002), and (7) regulated splicing and translation: Mbnl2 (Wang et al., 2012). The identification of Mbnl2 as a RBFox2 target gene exemplifies a potential cascade of regulated splicing events through RBFox2-regulated splicing regulators, given the recent observation that RBFox2 appears to function as a key regulator of splicing factors (Jangi et al., 2014). In fact, we noted that Ndrg2, a key gene involved in cardioprotection (Sun et al., 2013), had been previously reported to a target gene for the Mbnl family of splicing regulators (Du et al., 2010). Together, these data suggest that RBFox2 modulates diverse regulatory functions in cardiomyocytes (Figure 6D). Although individual mRNA isoforms of these genes remain to be functionally characterized, it is likely that the reversal of these developmentally regulated splicing program may collectively contribute to heart failure in TAC-treated and RBFox2 knockout mice.

Discussion

RBFox2 controls a large splicing program in the heart

RBFox2 has emerged as a key tissue-specific regulator of alternative splicing in development and disease through recognizing the conserved GUAUG motif in metazoans (Zhang et al., 2008). In mammalian heart, RBFox2 is expressed in a relatively constant fashion, in contrast to the dramatic induction of the related RBFox1 protein after birth (Kalsotra et al., 2008), which may together regulate and maintain a key splicing program functionally important for postnatal heart remodeling. Such a synergistic function between RBFox1 and RBFox2 has been demonstrated in zebrafish heart development (Gallagher et al., 2011). Intriguingly, RBFox2 appears to play a more important role than RBFox1 in C2C12 cells (Singh et al., 2014), and the lethal phenotype observed on RBFox2 ablated mice clearly demonstrated its unique contribution to cardiac function, which is consistent with the large altered splicing program in RBFox2 knockout cardiomyocytes despite the continuous presence of RBFox1.

It is interesting to note that RBFox2-ablated mice were relatively morphologically normal until five weeks after birth, indicating that RBFox2 is critical for heart performance. By splicing profiling, we identified a large number of RBFox2 direct target genes based on direct binding evidence and resultant RNA map that shows the anticipated positional effects. Importantly, these RBFox2 target genes provide diverse cardiac functions, ranging from key components of the contractile apparatus to various ion channels and signaling molecules critical for coupling between excitation and contraction to genes involved in energy metabolism, as highlighted in Figure 6D. The RBFox2-regulated splicing program is likely further amplified via its immediate target genes, which include the MEF family of muscle-specific transcription factors and other critical splicing regulators (such as Mbnl2), eventually causing mortality of RBFox2 knockout mice.

RBFox2 may serve as a key sensor to stress signaling

Our current targeting study is of physiological relevance because of the link of diminished RBFox2 protein to pressure overloading. This implicates RBFox2 as a key sensor to stress signaling in the heart. Interestingly, its mRNA level appears unaltered as evidenced by multiple probe signals in our RASL-seq oligonucleotide pool that remain unchanged in TAC-treated mice. This suggests that RBFox2 protein might be down regulated via a post-translational mechanism(s), which is subjected to future studies. Such unaltered mRNA would escape the detection in previous gene expression profiling experiments on animal models (Zhao et al., 2004) or human patient samples (Kaynak et al., 2003). Unfortunately, such unstable protein in TAC-treated mice discouraged us to further evaluate RBFox2 reduction to TAC-induced phenotype with a transgene.

While it is currently unclear about the mechanism to trigger the reduction of RBFox2 protein in TAC-treated mice, the proposed sensor function raises an intriguing possibility that RBFox2 might be a key target in certain stress signaling pathways. In fact, diverse signal transduction pathways have been shown to accompany physiological heart modeling or pathological responses in failing heart (van Berlo et al., 2013). Therefore, it will be an important object for future studies to understand how RBFox2 expression is diminished in response to a specific stress signal(s). As its mRNA appears unaltered in TAC-treated heart, it will be particularly interesting to determine whether RBFox2 is a target for a pressure overloading-induced microRNA (Reddy et al., 2012). Proteasome-mediated degradation also remains a formal possibility to be tested in future investigation.

RBFox2 might be a key component of decompensation in failing heart

Mammalian genomes encode for a large number of RNA binding proteins, which together control an extensive alternative splicing program (Fu and Ares, 2014) in development and disease (Kalsotra and Cooper, 2011). Because alternative splicing often introduces subtle changes in mRNA that may alter RNA stability and/or function, it has remained a major challenge to infer functional consequences among numerous altered splicing events in a given cell type or biological system. Here, we took advantage of postnatal heart remodeling, a well-known positive force for augmentation of cardiac functions. By profiling splicing in this critical developmental window, we identified a set of alternative splicing events that are switched in a monotonic fashion. Importantly, many of those events were reversed in response to TAC treatment or RBFox2 ablation, thus consistent with comprised cardiac function via such a regulated splicing program. This includes F1γ (encoded by Atp5c1), one of the best biochemically characterized RBFox2 target genes (Fukumura et al., 2007), and splicing of this ATP synthetase gene is known to enhance energy production in the mitochondria of cardiac muscle (Hayakawa et al., 2002). Defects in this and other RBFox2 target genes may thus collectively contribute to heart failure in RBFox2 knockout mice.

Our functional study of RBFox2-regulated splicing on the mouse model also provides critical insights into cardiac decompensation, which is a key, but poorly understood process during heart failure. We found that RBFox2 ablation induced a failure phenotype without first induced cardiac hypertrophy, consistent with other genetic models in which compensation and decompensation appear decoupled (Diwan and Dorn, 2007). Our observations that TAC triggered a dramatic reduction in RBFox2 expression and both TAC and RBFox2 ablation produced related disease phenotypes and regulated a set of key alternative splicing events strongly suggest that RBFox2 may be a key component of cardiac decompensation. It will be of great interest to determine in future studies whether the RBFox2 level could be correlated to hypertension-induced cardiac malfunction in humans.

Experimental Procedures

Transaortic Banding Surgery

Nine-week-old male littermate mice were subjected to pressure overload by transaortic constriction (TAC) surgery, as described (Guo et al., 2014). After five weeks of surgery, total protein and RNA were extracted from isolated cardiomyocytes from Sham and TAC-treated mice for Western blotting, RASL-seq, and RT-PCR.

Generation of RBFox2 cardiac-specific knockout mice

The construction of conditional RBFox2 knockout mice has been previously described (Gehman et al., 2012). Crossing of the mice with the Mlc2v-Cre transgenic mouse and characterization of the mutant mice of genotypes are detailed in Extended Experimental Procedures. Specific siRNAs used in the current study are listed in Table S1.

Echocardiography and calcium imaging

Phenotypic and echocardiographic analyses of RBFox2 ablated heart were performed according to (Xu and Fu, 2005) and details are also provided in Extended Experimental Procedures.

RASL-seq profiling, data analysis, and RT-PCR validation

RASL-seq is designed to profile mRNA isoforms using pooled pairs of oligonucleotides each flanked by a universal primer to target specific splice junctions in spliced mRNAs, as previously described (Li et al., 2012), and are detailed in Extended Experimental Procedures. Significantly changed splicing events at different developmental stages in RBFox2 KO mice over WT are listed in Table S2 and those induced by TAC treatment over sham operation and those altered during postnatal heart development are listed in Table S3.

RBFox2 CLIP-seq

RBFox2 CLIP-seq and construction of the RBFox2 RNA map were previously detailed (Yeo et al., 2009). A rabbit polyclonal anti-RBFox2 antibody (Bethyl, A300-864A) was used to immunoprecipitate RBFox2-RNA complexes from isolated cardiomyocytes of week 9 mice hearts. For detailed analyses, see the data analysis in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to members of the Fu lab for cooperation, reagent sharing, and stimulating discussion during the course of this investigation. This work was supported by NIH grants (GM049369, HG004659, and HG007005) to X-D.F.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental information

Supplemental Information includes 5 figures, 3 tables, and Extended Experimental Procedures.

Accession Numbers

The RASL-seq, RNA-seq and CLIP-seq data presented in this report are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE57926.

References

- Aguilar F, Belmonte SL, Ram R, Noujaim SF, Dunaevsky O, Protack TL, Jalife J, Todd Massey H, Gertler FB, Blaxall BC. Mammalian enabled (Mena) is a critical regulator of cardiac function. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2011;300:H1841–1852. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01127.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienengraeber M, Olson TM, Selivanov VA, Kathmann EC, O'Cochlain F, Gao F, Karger AB, Ballew JD, Hodgson DM, Zingman LV, et al. ABCC9 mutations identified in human dilated cardiomyopathy disrupt catalytic KATP channel gating. Nature genetics. 2004;36:382–387. doi: 10.1038/ng1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kubalak SW, Chien KR. Ventricular muscle-restricted targeting of the RXRalpha gene reveals a non-cell-autonomous requirement in cardiac chamber morphogenesis. Development. 1998;125:1943–1949. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Craigen WJ, Riley DJ. Nek1 regulates cell death and mitochondrial membrane permeability through phosphorylation of VDAC1. Cell cycle. 2009;8:257–267. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.2.7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Kimura K, Peter AK, Cui L, Ouyang K, Shen T, Liu Y, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Evans SM, et al. Loss of enigma homolog protein results in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation research. 2010;107:348–356. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks. Physiological reviews. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer JM, Mao L, Rockman HA, Means AR. Pressure overload selectively up-regulates Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in vivo. Molecular endocrinology. 2003;17:183–192. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan A, Dorn GW., 2nd Decompensation of cardiac hypertrophy: cellular mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Physiology. 2007;22:56–64. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Cline MS, Osborne RJ, Tuttle DL, Clark TA, Donohue JP, Hall MP, Shiue L, Swanson MS, Thornton CA, et al. Aberrant alternative splicing and extracellular matrix gene expression in mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2010;17:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel BL, Wexler E, Wahnich A, Friedrich T, Vijayendran C, Gao F, Parikshak N, Konopka G, Geschwind DH. RBFOX1 regulates both splicing and transcriptional networks in human neuronal development. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21:4171–4186. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XD, Ares M., Jr. Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins. Nature reviews Genetics. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nrg3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumura K, Kato A, Jin Y, Ideue T, Hirose T, Kataoka N, Fujiwara T, Sakamoto H, Inoue K. Tissue-specific splicing regulator Fox-1 induces exon skipping by interfering E complex formation on the downstream intron of human F1gamma gene. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:5303–5311. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher TL, Arribere JA, Geurts PA, Exner CR, McDonald KL, Dill KK, Marr HL, Adkar SS, Garnett AT, Amacher SL, et al. Rbfox-regulated alternative splicing is critical for zebrafish cardiac and skeletal muscle functions. Developmental biology. 2011;359:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehman LT, Meera P, Stoilov P, Shiue L, O'Brien JE, Meisler MH, Ares M, Jr., Otis TS, Black DL. The splicing regulator Rbfox2 is required for both cerebellar development and mature motor function. Genes Dev. 2012;26:445–460. doi: 10.1101/gad.182477.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehman LT, Stoilov P, Maguire J, Damianov A, Lin CH, Shiue L, Ares M, Jr., Mody I, Black DL. The splicing regulator Rbfox1 (A2BP1) controls neuronal excitation in the mammalian brain. Nat Genet. 2011;43:706–711. doi: 10.1038/ng.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehmlich K, Pinotsis N, Hayess K, van der Ven PF, Milting H, El Banayosy A, Korfer R, Wilmanns M, Ehler E, Furst DO. Paxillin and ponsin interact in nascent costameres of muscle cells. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;369:665–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudice J, Xia Z, Wang ET, Scavuzzo MA, Ward AJ, Kalsotra A, Wang W, Wehrens XH, Burge CB, Li W, et al. Alternative splicing regulates vesicular trafficking genes in cardiomyocytes during postnatal heart development. Nature communications. 2014;5:3603. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A, Zhang X, Iyer VR, Chen B, Zhang C, Kutschke WJ, Weiss RM, Franzini-Armstrong C, Song LS. Overexpression of junctophilin-2 does not enhance baseline function but attenuates heart failure development after cardiac stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:12240–12245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412729111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M, Sakashita E, Ueno E, Tominaga S, Hamamoto T, Kagawa Y, Endo H. Muscle-specific exonic splicing silencer for exon exclusion in human ATP synthase gamma-subunit pre-mRNA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:6974–6984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JA, Karimi M, Kutschke W, Davisson RL, Zimmerman K, Wang Z, Kerber RE, Weiss RM. Cardiac hypertrophy is not a required compensatory response to short-term pressure overload. Circulation. 2000;101:2863–2869. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.24.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangi M, Boutz PL, Paul P, Sharp PA. Rbfox2 controls autoregulation in RNA-binding protein networks. Genes & development. 2014;28:637–651. doi: 10.1101/gad.235770.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsotra A, Cooper TA. Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011;12:715–729. doi: 10.1038/nrg3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsotra A, Xiao X, Ward AJ, Castle JC, Johnson JM, Burge CB, Cooper TA. A postnatal switch of CELF and MBNL proteins reprograms alternative splicing in the developing heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:20333–20338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809045105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaynak B, von Heydebreck A, Mebus S, Seelow D, Hennig S, Vogel J, Sperling HP, Pregla R, Alexi-Meskishvili V, Hetzer R, et al. Genome-wide array analysis of normal and malformed human hearts. Circulation. 2003;107:2467–2474. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066694.21510.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KK, Adelstein RS, Kawamoto S. Identification of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) as Fox-3, a new member of the Fox-1 gene family of splicing factors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:31052–31061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Bloch RJ. The hydrophilic domain of small ankyrin-1 interacts with the two N-terminal immunoglobulin domains of titin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:3985–3991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenz M, Robbins J. Impact of beta-myosin heavy chain expression on cardiac function during stress. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;44:2390–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroyanagi H. Fox-1 family of RNA-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3895–3907. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski AP, McGill JM. Alternative splice variant of gamma-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alters activation by calmodulin. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2000;378:377–383. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Qiu J, Fu XD. RASL-seq for massively parallel and quantitative analysis of gene expression. Current protocols in molecular biology / edited by Frederick M Ausubel [et al] 2012 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0413s98. Chapter 4, Unit 4 13 11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marber MS, Rose B, Wang Y. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway--a potential target for intervention in infarction, hypertrophy, and heart failure. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez J, Turner C, Avraham H, Steinberg SF, Schaefer E, Sussman MA. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis triggered by RAFTK/pyk2 via Src kinase is antagonized by paxillin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:53516–53523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuchamy M, Boivin GP, Grupp IL, Wieczorek DF. Beta-tropomyosin overexpression induces severe cardiac abnormalities. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 1998;30:1545–1557. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuchamy M, Pajak L, Howles P, Doetschman T, Wieczorek DF. Developmental analysis of tropomyosin gene expression in embryonic stem cells and mouse embryos. Molecular and cellular biology. 1993;13:3311–3323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponthier JL, Schluepen C, Chen W, Lersch RA, Gee SL, Hou VC, Lo AJ, Short SA, Chasis JA, Winkelmann JC, et al. Fox-2 splicing factor binds to a conserved intron motif to promote inclusion of protein 4.1R alternative exon 16. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:12468–12474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S, Zhao M, Hu DQ, Fajardo G, Hu S, Ghosh Z, Rajagopalan V, Wu JC, Bernstein D. Dynamic microRNA expression during the transition from right ventricular hypertrophy to failure. Physiological genomics. 2012;44:562–575. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00163.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig R, Bronner V, Zhang D, Fushman D, Glickman MH. Rpn1 and Rpn2 coordinate ubiquitin processing factors at proteasome. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:14659–14671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato PY, Coombs W, Lin X, Nekrasova O, Green KJ, Isom LL, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Interactions between ankyrin-G, Plakophilin-2, and Connexin43 at the cardiac intercalated disc. Circulation research. 2011;109:193–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck A, Bardoni B, Langmann C, Harden N, Mandel JL, Giangrande A. CYFIP/Sra-1 controls neuronal connectivity in Drosophila and links the Rac1 GTPase pathway to the fragile X protein. Neuron. 2003;38:887–898. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, Yamrom B, Yoon S, Krasnitz A, Kendall J, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Xia Z, Bland CS, Kalsotra A, Scavuzzo MA, Curk T, Ule J, Li W, Cooper TA. Rbfox2-Coordinated Alternative Splicing of Mef2d and Rock2 Controls Myoblast Fusion during Myogenesis. Molecular cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg MA, Carter E, Sohrabi N, Siedlecka U, Soppa GK, Mead F, Mohandas N, Taylor-Harris P, Baines A, Bennett P, et al. Cytoskeletal protein 4.1R affects repolarization and regulates calcium handling in the heart. Circulation research. 2008;103:855–863. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunnenberg BC, Deinum J, Links TP, Wilde AA, Franssen H, Drost G. Cardiac arrhythmias in hypokalemic periodic paralysis: Hypokalemia as only cause? Muscle & nerve. 2014;50:327–332. doi: 10.1002/mus.24225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Tong G, Ma N, Li J, Li X, Li S, Zhou J, Xiong L, Cao F, Yao L, et al. NDRG2: a newly identified mediator of insulin cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic research in cardiology. 2013;108:341. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berlo JH, Maillet M, Molkentin JD. Signaling effectors underlying pathologic growth and remodeling of the heart. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:37–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI62839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables JP, Klinck R, Koh C, Gervais-Bird J, Bramard A, Inkel L, Durand M, Couture S, Froehlich U, Lapointe E, et al. Cancer-associated regulation of alternative splicing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Cody NA, Jog S, Biancolella M, Wang TT, Treacy DJ, Luo S, Schroth GP, Housman DE, Reddy S, et al. Transcriptome-wide regulation of pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA localization by muscleblind proteins. Cell. 2012;150:710–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Bhattacharyya B, Rachel RA, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Householder DB, Fletcher CF, Miller RJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Synaptic defects in ataxia mice result from a mutation in Usp14, encoding a ubiquitin-specific protease. Nature genetics. 2002;32:420–425. doi: 10.1038/ng1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Fu XD. Conditional knockout mice to study alternative splicing in vivo. Methods. 2005;37:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Shirayama T, Sakatani T, Takahashi T, Tanaka H, Takamatsu T, Spitzer KW, Matsubara H. Enhanced activity of ventricular Na+-HCO3-cotransport in pressure overload hypertrophy. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2007;293:H1254–1264. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00964.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang RF, Zhao GW, Liang ST, Zhang Y, Sun LH, Chen HZ, Liu DP. Mitofilin regulates cytochrome c release during apoptosis by controlling mitochondrial cristae remodeling. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;428:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo GW, Coufal NG, Liang TY, Peng GE, Fu XD, Gage FH. An RNA code for the FOX2 splicing regulator revealed by mapping RNA-protein interactions in stem cells. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:130–137. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung CK, Halperin VL, Tomaselli GF, Winslow RL. Gene expression profiles in end-stage human idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: altered expression of apoptotic and cytoskeletal genes. Genomics. 2004;83:281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang Z, Castle J, Sun S, Johnson J, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ. Defining the regulatory network of the tissue-specific splicing factors Fox-1 and Fox-2. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2550–2563. doi: 10.1101/gad.1703108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Chow A, Powers J, Fajardo G, Bernstein D. Microarray analysis of gene expression after transverse aortic constriction in mice. Physiological genomics. 2004;19:93–105. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00040.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Cheng H, Li X, Zhang J, Cui L, Ouyang K, Han L, Zhao T, Gu Y, Dalton ND, et al. Cardiac-specific ablation of Cypher leads to a severe form of dilated cardiomyopathy with premature death. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18:701–713. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Qiu J, Liu W, Zhou Y, Plocinik RM, Li H, Hu Q, Ghosh G, Adams JA, Rosenfeld MG, et al. The Akt-SRPK-SR axis constitutes a major pathway in transducing EGF signaling to regulate alternative splicing in the nucleus. Molecular cell. 2012;47:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Ramachandran B, Gulick T. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing governs expression of a conserved acidic transactivation domain in myocyte enhancer factor 2 factors of striated muscle and brain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:28749–28760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.