Abstract

Adjuvant chemotherapy is often needed to achieve adequate breast cancer control. The increasing popularity of immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) raises concerns that this procedure may delay the time to adjuvant chemotherapy (TTC), which may negatively impact oncological outcome. The current systematic review aims to investigate this effect. During October 2014, a systematic search for clinical studies was performed in six databases with keywords related to breast reconstruction and chemotherapy. Eligible studies met the following inclusion criteria: (1) research population consisted of women receiving therapeutic mastectomy, (2) comparison of IBR with mastectomy only groups, (3) TTC was clearly presented and mentioned as outcome measure, and (4) original studies only (e.g., cohort study, randomized controlled trial, case–control). Fourteen studies were included, representing 5270 patients who had received adjuvant chemotherapy, of whom 1942 had undergone IBR and 3328 mastectomy only. One study found a significantly shorter mean TTC of 12.6 days after IBR, four studies found a significant delay after IBR averaging 6.6–16.8 days, seven studies found no significant difference in TTC between IBR and mastectomy only, and two studies did not perform statistical analyses for comparison. In studies that measured TTC from surgery, mean TTC varied from 29 to 61 days for IBR and from 21 to 60 days for mastectomy only. This systematic review of the current literature showed that IBR does not necessarily delay the start of adjuvant chemotherapy to a clinically relevant extent, suggesting that in general IBR is a valid option for non-metastatic breast cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10549-015-3539-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Immediate breast reconstruction, Chemotherapy, Mastectomy, Breast cancer, Systematic review

Introduction

One out of every eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in her lifetime, making it the most common cancer in women [1]. Over the last decades the survival rate has increased slowly, which is currently estimated to be 85 % in developed countries [2]. However, with an estimated annual number of breast cancer deaths of 537,000 worldwide, breast cancer still is the most important cause of death by cancer among women [3].

Despite advances in different treatment modalities, about 45 % of all breast cancer patients still undergoes a mastectomy for adequate local control [4, 5]. The resulting loss of a breast may have a negative effect on body image, sexuality, and sense of femininity [6]. Breast reconstruction aims to diminish the negative psychological impact of mastectomy and to improve patients’ quality of life. Currently, approximately 20–40 % of women who undergo a mastectomy receive breast reconstruction [1]. Breast reconstruction can either be performed immediately following mastectomy during the same operation or as a delayed procedure after completion of the entire oncologic treatment. Immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) has several reported advantages, such as favorable esthetic outcomes and less psychological burden, avoiding additional operations, hospitalizations, and costs [4].

A disadvantage of IBR is the increased risk of postoperative complications, which causes concerns regarding oncological safety [7]. Almost 39 % of medical oncologists and 23 % of surgical oncologists feel that breast reconstruction adversely interferes with adjuvant oncological therapy [8]. One concern is that IBR increases the time to adjuvant chemotherapy (TTC), which may have a negative impact on recurrence and survival rates. To put a possible delay in the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy into perspective, it needs to be established from which point on this delay negatively affects oncological safety and, hence, becomes clinically relevant.

Various studies aimed at identifying the cut-off point after which increased TTC has a significant negative impact on survival. In relation to relapse-free survival, disease-free survival or overall survival in non-metastatic breast cancer patients, no such cut-off point has been identified, given chemotherapy was started within 3 months after surgery [9–13]. One study, however, identified a subgroup of premenopausal patients with ER-negative node-positive tumors who showed impaired disease-free survival if chemotherapy was started 21–86 days versus within 20 days after surgery [10]. Furthermore, in patients with stage I or II breast cancer relapse-free survival and overall survival were found to significantly decrease if chemotherapy was postponed more than 3 months after surgery [12].

The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review of the current literature to investigate whether TTC is affected by IBR compared with mastectomy only.

Methods

Within the databases Embase, Medline (PubMed), Web of Science, Scopus, the Cochrane Central, and Google Scholar studies on the effect of IBR on TTC in breast cancer patients were searched on 6 October 2014. Keywords related to breast reconstruction, chemotherapy, and a clinical study design were used. The exact search string is shown in the appendix. No limitations were placed on study design, language, or otherwise. References were checked for duplicity and deleted accordingly.

Two reviewers (JXH and CAEK) independently assessed the title and abstract of all references with the following inclusion criteria: (1) the research population consists of women undergoing a mastectomy for breast cancer, (2) the study compares a cohort receiving IBR with one receiving mastectomy only, (3) timing of adjuvant chemotherapy is mentioned as outcome measure and is appropriately quantified, and (4) the publication concerns an original study (i.e., cohort study, randomized controlled trial, case–control, case study). Conference abstracts and reviews were excluded. In case of disagreement between two reviewers, a third reviewer (EB) made the final decision.

Subsequently, the full text of the selected studies was reviewed for final inclusion. If deemed necessary, authors were contacted with a request to provide additional information or clarification. Next, the reference lists of these finally included studies were searched for references to other relevant studies, which had not been included in the original search. The selection of these references was performed using the same criteria as mentioned above.

Study quality was assessed through an estimation of bias due to various causes [14]. Data were extracted using a predefined extraction form. Information was obtained on study design, patient characteristics (including comorbidities), outcome measures regarding TTC, and variables regarding other aspects of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Statistical analysis

If only median values were reported, authors were contacted with a request to provide mean values and standard deviations, to enable us to calculate 95 % confidence intervals of the mean differences.

Clinical and statistical heterogeneity were assessed and, if deemed sufficiently low, a meta-analysis was performed using pooled data. Statistical heterogeneity was determined using the I2 index. An I2 value smaller than 25 % was considered to indicate low heterogeneity, a value of 25–50 % moderate heterogeneity, and a value above 50 % high heterogeneity [15]. If I2 was low or moderate a fixed effects model was used, whereas we used a random effects model if the I2 index indicated high heterogeneity. Overall effect was calculated as a Z-statistic, with 95 % confidence intervals, and regarding a p value less than 0.05 as significant. Review Manager 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

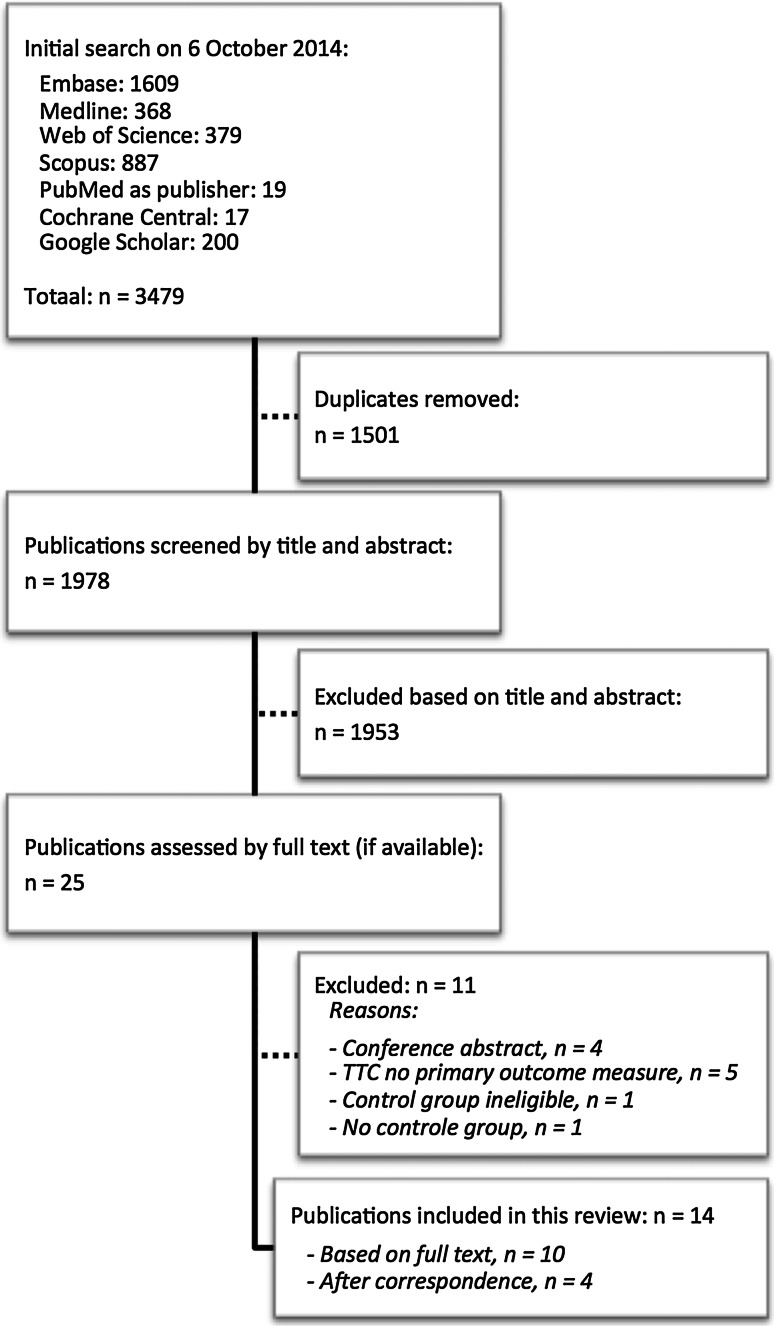

The literature search yielded 1978 unique publications and after applying the selection criteria 25 publications were read in full text, of which 14 were finally included (Fig. 1) [7, 16–28]. The initial consensus between the reviewers after screening of title and abstract was 99.4 %. Screening of the reference lists of the included papers did not result in the inclusion of additional studies. Four studies were included only after essential information was acquired through correspondence with the authors [19, 20, 25, 27]. Extra information was received for three other studies as well [7, 21, 23].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study selection procedure

Study characteristics and quality

The study characteristics are shown in Table 1. As expected, no randomized controlled trials were found on IBR and adjuvant chemotherapy. All included studies were retrospective cohort studies, of which one used matching to define a control cohort. It should be noted that Alderman et al. [16] and Vandergrift et al. [27] partly cover the same patient population for the entire year of 2003.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies on IBR and adjuvant chemotherapy

| Year of publication | Research period | Country | Typea | Center | Patient recruitment (and extra data source) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderman [16] | 2010 | 1997–2003 | USA | RCS | Multi | Prospectively maintained database |

| Allweis [17] | 2002 | 1996–2000 | USA | RCS | Single | Hospital tumor registry (and medical records) |

| Chang [18] | 2013 | 2003–2009 | Australia | RCS | Single | Prospectively maintained database |

| Eriksenb [19] | 2011 | 1990–2004 | Sweden | RMCS | Single | Prospectively maintained database |

| Hamahatab [20] | 2013 | 2006–2011 | Japan | RCS | Single | Medical records |

| Kahnb [21] | 2013 | 2008–2011 | UK | RCS | Single | Prospectively maintained database (and medical records) |

| Lee [22] | 2011 | 2008–2010 | Korea | RCS | Single | Institutional electronic patient database and medical records |

| Mortensonb [23] | 2004 | 1995–2002 | USA | RCS | Single | Medical records |

| Newman [24] | 1999 | 1990–1993 | USA | RCS | Single | Prospectively maintained database |

| Reyb [25] | 2005 | 1999–2002 | Italy | RCS | Single | ? |

| Taylor [26] | 2004 | 1999–2002 | UK | RCS | Single | Regional tumor registry |

| Vandergriftb [27] | 2013 | 2003–2009 | USA | RCS | Multi | Prospectively maintained database (and medical records) |

| Wilson [28] | 2004 | 1995–2000 | UK | RCS | Single | Database (and the case notes crosschecked with the pharmacy records) |

| Zhongb [7] | 2012 | 2007–2010 | Canada | RCS | Single | Prospectively maintained database |

IBR immediate breast reconstruction

a RCS retrospective cohort study; RMCS retrospective matched cohort study

bAdditional information about this paper was required through correspondence with the authors

The results of the quality assessment are shown in Table 2. Few studies reported information about follow-up. In most studies patients were included if they received chemotherapy and therefore patients who started chemotherapy late may have been missed if follow-up was insufficient to identify them.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies on IBR and adjuvant chemotherapy

| Study | Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients | Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment group | Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcomes | Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors | Unclear or inconsistent reported outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderman [16] | UL | UL | UL | Lf | No |

| Allweis [17] | UL | ? | UL | Lg | Yesi |

| Chang [18] | UL | ? | UL | Lg | No |

| Eriksena [19] | UL | Lc | UL | Lh | No |

| Hamahataa [20] | UL | ? | UL | Lg | Yesi |

| Kahna [21] | UL | ? | Ld | Lh | No |

| Lee [22] | UL | ? | UL | Lg | No |

| Mortensona [23] | UL | ? | UL | Lh | Yesi |

| Newman [24] | UL | UL | UL | Lh | No |

| Reya [25] | ?b | UL | UL | Lg | Yesj |

| Taylor [26] | UL | ? | UL | Lh | No |

| Vandergrifta [27] | UL | UL | ULe | Lf | No |

| Wilson [28] | ?b | ? | UL | Lh | Yesi |

| Zhonga [7] | UL | ? | UL | Lg | No |

UL unlikely; ? unclear; L likely; IBR immediate breast reconstruction; CTx adjuvant chemotherapy; TTC Time to adjuvant chemotherapy

aAdditional information about this paper was required through correspondence with the authors

bPatient selection unclear

cLost to follow-up for TTC: 15 and 24 % for IBR and mastectomy, respectively

dTTC measured from multidisciplinary decision to administer adjuvant treatments instead of final operation, allowing for other factors than type of operation to affect TTC, which is inconsistent with the study purpose

eAlternative definition for TTC, but consistent with the study purpose

fCorrected for some but not all. For example type of reconstruction and smoking behavior were omitted

gSome data on possible confounders reported, but adjusted for none

hDid not report data on possible confounders for patients receiving CTx

iDifferent values for the same outcome measure reported

jType of point estimator not stated (clarified by e-mail)

Table 3 shows the patient characteristics of the studies included in the current review. Few studies reported data on patient age, comorbidity, and risk factors for postoperative complications and even fewer studies reported these characteristics specifically for patients who had received chemotherapy. Therefore, it was not possible to provide an overview of these variables.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics of the included studies on IBR and adjuvant chemotherapy Patients receiving CTx/Total in cohort (%)

| Study | Patient population | Exclusion criteria | Type of reconstruction | Patients receiving CTx/Total in cohort (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous | TE/I | LD | IBR | M | |||

| Alderman [16] | Women with stage I–III unilateral breast cancer for whom guidelines recommended CTx | nCTx; nRTX; RTx before CTx; breast reconstruction >1 day after M, but after CTx | 52 %b | 48 %b | 0 %b | 499/499 (100) | 573/573 (100) |

| Allweis [17] | All breast cancer patients who were treated at institution and received CTx | nCTx | 53 % | 37 % | 10 % | 49/49 (100) | 308/308 (100) |

| Chang [18] | Patients who underwent M with or without IBR and received CTx | nCTx | 3 % | 97 % | 0 % | 107/107 (100) | 103/103 (100) |

| Eriksena [19] | Patients with invasive breast cancer and implant-based reconstruction matched for age, tumor size, nodal status, and year of operation to M only patients | Previous ipsilateral surgery | 0 % | 100 % | 0 % | 132/300 (44) | 138/300 (46) |

| Hamahataa [20] | Patients who underwent M with or without IBR and received CTx | – | 18 % | 34 % | 48 % | 50/50 (100) | 66/66 (100) |

| Kahna [21] | Patients who underwent OBCS, WLE, or M with or without IBR and received CTx | nCTx | NR | NR | NR | 16/16 (100) | 56/56 (100) |

| Lee [22] | Female breast cancer patients who underwent M with or without IBR and received CTx | nCTx; CTx delayed by patient; patients participating in other studies associated with CTx | 21 % | 47 % | 33 % | 43/43 (100) | 552/552 (100) |

| Mortensona [23] | Women who underwent M for breast cancer | Skin graft used; insufficient follow-up; different indication for CTx; nCTx | 29 % | 61 % | 10 % | 42/62 (68) | 39/66 (59) |

| Newman [24] | Patients with LABC who underwent M with IBR or without IBR, but with nCTx, CTx, and RTx. | – | 68 % | 30 % | 2 % | 48/50 (96) | 72/72 (100) |

| Reya [25] | All patients receiving high-density CTx | Flap reconstructions | 0 % | 100 % | 0 % | 23/23 (100) | 15/15 (100) |

| Taylor [26] | Newly diagnosed breast cancer patients who underwent M with or without IBR and received CTx | nCTx | 50 % | 16 % | 34 % | 44/44 (100) | 49/49 (100) |

| Vandergrifta [27] | Women with stage I-III unilateral breast cancer receiving CTx | nCTx; nRTx; Unknown type or date of definitive surgery; Follow-up < 180 days; RTx before CTx; CTx elsewhere; TTC > 32 weeks | NR | NR | NR | 784/784 (100) | 1166/1166 (100) |

| Wilson [28] | Breast cancer patients receiving CTx and BCS, M or IBR. | – | 51 % | 22 % | 27 % | 95/95 (100) | 95/95 (100) |

| Zhonga [7] | Woman who underwent M | nCTx | Yes | Yes | Maybe | 10/148 (7) | 96/243 (40) |

TE/I tissue expander and/or implants; LD latissimus dorsi with or without implant; IBR immediate breast reconstruction; M mastectomy; CTx adjuvant chemotherapy; nCTx neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nRTx neoadjuvant radiotherapy; RTx radiotherapy; OBCS oncoplastic breast conserving surgery; WLE wide local excision; BCS breast conserving surgery; NR not reported; TTC time to chemotherapy

aAdditional information about this paper was required through correspondence with the authors

bAlso concerns 90 delayed reconstructions and the autologous group possibly contains LD reconstructions

Study heterogeneity

The patient populations were compared regarding the inclusion criteria used and the available patient characteristics in order to determine the clinical heterogeneity. Due to lack of pertinent information, the legitimacy to do a meta-analysis was doubted. Moreover, an I2 of 98 % was observed, after pooling the studies that used the same definition for time to chemotherapy and reported mean values and standard deviations [7, 17, 20, 22, 23], indicating a high statistical heterogeneity. We found no obvious explanation for this high statistical heterogeneity. Consequently, no meta-analysis was performed.

Time to chemotherapy

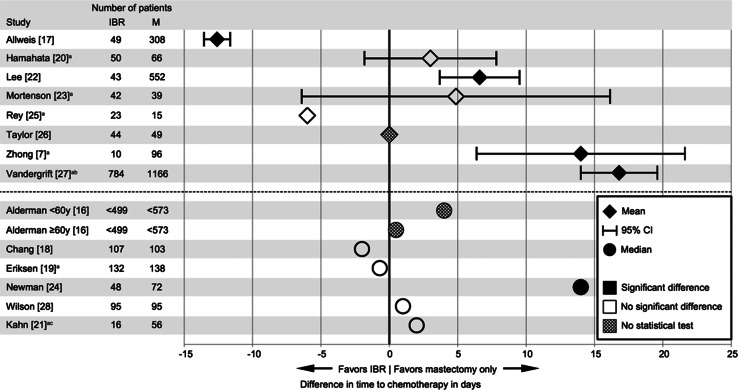

The included studies reported TTC in different formats (Table 4 and Fig. 2). Originally, seven studies reported TTC as a mean value and seven as a median value. The authors of one of the studies that reported medians provided us with means and standard deviations on request [7]. If the required information was available, the 95 % confidence interval was computed for the mean differences. Alderman et al. [16] only reported values for two separate age groups instead of the total patient group.

Table 4.

Outcome measures of the included studies on IBR and adjuvant chemotherapy

| Study | Type | Starting point of interval to chemotherapy | ∆ Time to chemotherapy in days | 95 % CI of ∆Mean | P value | Immediate breast reconstruction | Mastectomy only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to chemotherapy in days | SD [Range] in days | N | Time to chemotherapy in days | SD [Range] in days | N | ||||||

| Allweis [17] | Mean | Surgery | −12.6 | −13.56; −11.64 | 0.039 | 40.6 | 3.3 [14–131] | 49 | 53.2 | 2.4 [1–215] | 308 |

| Hamahataa [20] | Mean | Surgery | 3 | −1.82; 7.82 | 0.25 | 61 | 13.7 | 50 | 58 | 12.3 | 66 |

| Lee [22] | Mean | Surgery | 6.6 | 3.68; 9.52 | <0.0001 | 31.5 | 9.6 | 43 | 24.9 | 6.5 | 552 |

| Mortensona [23] | Mean | Surgery | 4.9 | −6.41; 16.15 | 0.40 | 51.7 | 29.8 | 42 | 46.8 | 21.6 | 39 |

| Reya [25] | Mean | Surgery | −6 | – | 0.13 | 54 | – | 23 | 60 | – | 15 |

| Taylor [26] | Mean | Surgery | 0 | – | – | 38 | – | 44 | 38 | – | 49 |

| Zhonga [7] | Mean | Surgery | 14.0 | 6.4; 21.6 | 0.01 | 60.9 | 10.5 [44.1–77] | 10 | 46.9 | 23.8 [4.9–105] | 96 |

| Vandergrifta [27] | Mean | Pathological diagnosis | 16.8 | 14.0; 19.6 | – | 96.6 | 32.2 | 784 | 79.8 | 30.1 | 1166 |

| Alderman <60 year [16] | Median | Surgery | 4.0 | – | 39.0 | – | – | 35.0 | – | – | |

| Alderman > 60 year [16] | Median | Surgery | 0.5 | – | 41.5 | – | – | 41.0 | – | – | |

| Chang [18] | Median | Surgery | −2 | 0.22 | 32 | 13 [17–88]b | 107 | 34 | 14 [15–119]b | 103 | |

| Eriksena [19] | Median | Surgery | −0.7 | 0.376 | 35.0 | [14–154] | 112 | 35.7 | [14–231] | 105 | |

| Newman [24] | Median | Surgery | 14 | 0.05 | 35 | [5–91] | 48 | 21 | [8–145] | 72 | |

| Wilson [28] | Median | Surgery | 1 | 0.12c | 29 | [17–55] | 95 | 28 | [16–52] | 95 | |

| Kahna [21] | Median | Multidisciplinary decision on adjuvant treatments | 2 | 0.26 | 31 | [15–58] | 16 | 29 | [15–57] | 56 | |

aAdditional information about this paper was acquired through correspondence with the authors

bInterquartile range

c χ 2 test together with a third patient cohort

Fig. 2.

Differences between IBR and mastectomy only in time to chemotherapy in days. IBR immediate breast reconstruction; M mastectomy only. aAdditional information about this paper was required through correspondence with the authors. bTime to chemotherapy measured from pathological diagnosis. cTime to chemotherapy measured from multidisciplinary decision

In the twelve studies that measured TTC from surgery, it varied between 29 and 61 days in the IBR groups and between 21 and 60 days in the patient groups that received mastectomy only. Differences in TTC between the IBR groups and the mastectomy only groups varied widely from a 12.6 days reduction in average TTC after IBR to a delay of 11.9 days in average TTC after IBR [7, 16–20, 22–26, 28]. One study found a significantly shorter TTC after IBR [17], three studies found a statistically significant delay following IBR [7, 22, 24], six studies found no statistically significant difference in TTC between IBR and mastectomy only [18–20, 23, 25, 28], and two studies did not perform a statistical test for the comparison [16, 26].

Two studies used a different definition for TTC. Kahn et al. [21] measured TTC starting from the multidisciplinary decision to administer adjuvant treatment and reported a TTC of 31 days for IBR and of 29 days for mastectomy only, resulting in a statistically non-significant difference of 2 days. TTC was measured from pathological diagnosis by Vandergrift et al. [27], reporting 96.6 days for IBR and 79.8 days for mastectomy only, with a difference of 16.8 days. It was clarified via correspondence that this multidisciplinary decision was made after surgery (L. Romics Jr., personal communication), whereas the pathological diagnosis was made before the operation. These differences in definitions should be kept in mind when evaluating and comparing TTC published in the different studies.

Comparing the upper ranges gives insight of the TTC for the extremes in each cohort. Those maximum values were similar or lower for the IBR groups than for the mastectomy only groups. Furthermore, in 4 out of 6 studies presenting ranges, all patients started chemotherapy within 13 weeks after IBR.

Two studies performed a multivariate analysis correcting for various sociodemographic, clinical, therapeutic, and diagnostic factors. Alderman et al. [16] found a significantly shorter TTC for patients younger than 40 years after mastectomy only; at older ages no significant differences were found between IBR and mastectomy only. Vandergrift et al. [27] found a significantly shorter TTC following mastectomy only, even after multivariate correction.

Other chemotherapy-related outcomes

Six studies reported the number of patients that had received chemotherapy after a certain point in time in the comparison of IBR with mastectomy only. Different cut-off points were chosen: two studies chose 8 weeks, three studies chose 12 weeks, and one study reported the number of patients per 10 days. No statistically significant differences for this comparison were found for these cut-off points [7, 16, 18, 20, 22, 26]. In patients with IBR, the few delays beyond 12 weeks after surgery were not related to the type of surgery, but due to social reasons and delayed diagnostic test results [7, 20].

Out of eight included studies which reported the occurrence of complications, two studies found significantly more complications in the IBR group [22, 23] and six studies did not find a significant difference (in one study after adjusting for confounders) between IBR and mastectomy only [7, 18–20, 24, 25]. Three studies evaluated the effect of these complications on TTC. One study showed a significantly longer TTC for patients with complications compared to patients without complications [22]. However, for patients with complications none of these studies showed a statistically significant difference in TTC between the IBR and mastectomy only groups [20, 22, 23].

Four studies that looked at TTC after various types of breast reconstruction could not find statistically significant differences [17, 20, 22, 28]. There were also no significant differences reported between IBR and mastectomy only in delay relative to planned initiation, dose reduction, delay during cycles or incomplete regimens [18, 19, 23, 26].

Besides TTC, omission of chemotherapy may influence oncological outcome. Only one study investigated this. Patients were included if they required adjuvant chemotherapy according to treatment guidelines. No statistically significant difference in omission of chemotherapy was found between the IBR and mastectomy group [16].

Discussion

This systematic review shows that IBR does not necessarily delay the start of adjuvant chemotherapy to a clinically relevant extent [9–13]. Differences in TTC between the IBR groups and the mastectomy only groups varied widely, ranging from a 12.6-day shorter TTC for IBR to a 16.6-day shorter TTC for mastectomy only. Out of 14 studies 10 studies reported a difference in TTC of less than a week between these two groups. Two important reasons for delay of chemotherapy may equally apply to any surgery: difficulties in planning the surgery and surgical complications.

First, difficulties in planning a multidisciplinary surgery such as IBR, probably delays start of chemotherapy. This is an explanation for the average delay of 16.6 days found by Vandergrift et al. as they measured the interval from pathological diagnosis to chemotherapy [27]. In this approach factors other than the surgical procedure itself will affect the measurement. For example, planning IBR surgery most likely takes more time than planning a mastectomy only, due to additional outpatient visits of different specialists before surgery, more operation time, and extra surgeons are necessary for performing IBR compared to mastectomy. All other studies measured TTC as of the date of surgery or multidisciplinary decision and were therefore incapable of identifying possible delays due to logistical difficulties in planning IBR. Besides planning of the surgery, other factors may influence TTC, such as different local protocols and the person deciding on the actual start of chemotherapy. Delays due to difficulties planning surgery may be reduced in case adequate logistical measures are taken. For example, scheduling the availability of a combined oncologic and plastic surgery operation room for IBR at regular intervals. In case of relatively long absolute TTC, local treatment protocols should be reassessed. With the growing trend towards multidisciplinary approach in health care generally, efficient planning and adequate protocols are key to avoid unnecessary delays. Such difficulties should not reduce the usage of multidisciplinary therapies such as IBR.

Second, the studies included in this review suggest that complications after IBR do not result in longer TTC compared to complications after mastectomy only. Complications in general are considered to delay chemotherapy and this was confirmed in one study recording a longer TTC for patients with complications compared to patients without complications [22]. There was no conclusive evidence that IBR gave rise to more complications than mastectomy only. Six studies found no difference in complication rate [7, 18–20, 24, 25]. One of them reported more complications with IBR in unadjusted data, but not after correction for confounders (previous surgery, previous radiotherapy, bilateral surgery) [7]. Two studies found more complications in the IBR group, but did not collect data on these confounders or did not correct for them while there were clear differences between the treatment groups [22, 23]. One study showed bilateral breast surgery results in more complications, although not proportionally more than two unilateral breast surgeries. Since the feasibility of IBR might increase the demand on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy by women with unilateral breast cancer, as a consequence the absolute number of complications may increase compared to unilateral breast surgery [29]. None of these studies showed a statistically significant difference in TTC between the IBR and mastectomy only groups for patients with complications [20, 22, 23].

The clinical relevance of a delay must be assessed in relation to absolute findings of TTC. No study reported an average interval from surgery to start of chemotherapy longer than the clinically relevant limit of 12 weeks after surgery [12]. As mentioned before, variation in commencement date of chemotherapy within 3 months maximum after surgery does not seem to have a significant effect on survival rates [9–13]. Consequently, no major impact on oncological safety is to be expected due to the reported average delays in TTC.

There are a few limitations to this review. Our quality assessment showed that most studies were potentially subject to bias. However, this was not to such an extent that a specific study had to be excluded from the review. It proved difficult to specifically examine the effect of IBR on TTC, because the majority of the studies reported general patient characteristics only without possible confounders or correcting for them. Some studies showed considerable differences in patient characteristics between the IBR and mastectomy only group. Furthermore, it is plausible that different types of breast reconstruction may have different effects on TTC, but only four studies investigated this issue. These studies did not find statistically significant differences, which may be due to small patient numbers [17, 20, 22, 28]. In two studies that corrected for various possible confounders, a statistically significant delay in TTC associated with IBR was found [16, 27]. In one study this finding was restricted to patients under 40 years of age [16]. Many studies used the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy as an inclusion criterion. It is possible that certain patients were missed out, in which case they received chemotherapy at another institution or at a later point in time than the follow-up period. Unfortunately, follow-up was not specifically reported in most studies. One study explicitly recorded that patients whose chemotherapy started more than 32 weeks after diagnosis were excluded [27]. As a result there may be bias, because patients with chemotherapy delayed beyond that period are taken out of the equation.

Since most studies report only on TTC as an average, they do not provide a basis for identifying outliers. Increased oncological risk may impact the few patients subject to the longest delays. Regardless, there was no significant difference in the number of patients with a TTC longer than 8 between IBR and mastectomy only [16, 18]. The same goes for patients with a TTC longer than 12 weeks [7, 20, 22]. The reasons given for the limited number of delays beyond 12 weeks after surgery were unrelated to the type of surgery, but due to social reasons and delayed diagnostic test results. The upper ranges of TTC were favorable for IBR.

Patients most susceptible for negative effects of delay may be those with the most aggressive tumors and metastatic disease. However, it is not really clear what the effect of delay in TTC is for those patients. Consequently, any delay due to IBR is of greater concern in this particular patient population. This systematic review did not include an analysis of the effect of IBR on TTC for specific subgroups potentially at risk [10], because the included studies did not provide data for such subgroups.

Beside the effect of IBR on TTC, there are concerns about postoperative morbidity resulting from the combination of IBR with radiotherapy or chemotherapy. First, a meta-analysis showed a negative effect on postoperative morbidity in patients receiving immediate breast reconstruction in case of adjuvant radiotherapy. However, delaying breast reconstruction until radiotherapy is finished did not improve postoperative morbidity. Autologous reconstruction resulted in less postoperative morbidity than implant-based reconstructions [30]. Second, IBR seems safe in patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, as this did not increase the complication rate [31]. The marginal delay in delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy could be an argument to support the growing popularity of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Third, one review suggested that the combination of IBR and adjuvant chemotherapy does not have a negative effect on surgical complications, postoperative wound healing, chance of reconstructive failure, or esthetic outcomes [32]. Finally, the effect of IBR on the oncological outcome in terms of recurrences is an issue. However, a meta-analysis comparing local and systemic recurrence rates after IBR and mastectomy only in locally advanced breast cancer patients did not show statistically significant differences [33].

Presently available evidence shows that IBR is safe with regard to the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy. Nevertheless, future developments in breast cancer treatment may require a reassessment. Future studies should identify and report possible confounders and adjust for them. In addition, inclusion and analysis of local protocols on the planning of adjuvant chemotherapy will be helpful to put the findings into perspective. Most studies included in this review had risk of bias, which further research should try to avoid, in order to allow for more reliable conclusions. It would seem important to further analyze the effect of IBR on other chemotherapy-related outcomes, such as dose reduction, delay during cycles, incomplete regimens or omission, as these also represent aspects of oncological safety. Finally, a systematic evaluation of the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on breast reconstruction in terms of complication rates, esthetic outcome, and patient satisfaction would be required for more detailed and conclusive findings outside the scope of this review.

In conclusion, after critical appraisal of the current literature, we found that IBR does not necessarily delay chemotherapy to a clinically relevant extent. With efficient logistics and adequate treatment protocols the risk of crossing the described 12-week barrier can be avoided. This would suggest that in general IBR is a valid option for non-metastatic breast cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. B.S. Niël-Weise, M.D., epidemiologist, from the Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten for her assistance with the study design and statistical analysis and Mr W.M. Bramer, biomedical information specialist, for help with the literature search.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Breast cancer facts & figures 2013–2014. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer . World cancer report 2008. France: Lyon; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Global health estimates 2014 summary tables: deaths by cause, age and sex, 2000–2012. Geneva: Global Health Estimates; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry MG, Gomez KF. Surgical techniques in breast cancer: an overview. Surgery (Oxford) 2013;31(1):32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mpsur.2012.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragun AE, Huang B, Tucker TC, Spanos WJ. Increasing mastectomy rates among all age groups for early stage breast cancer: a 10-year study of surgical choice. Breast J. 2012;18(4):318–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopie JP, Hilhorst MT, Kleijne A, Timman R, Menke-Pluymers MB, Hofer SO, et al. Women’s motives to opt for either implant or DIEP-flap breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(8):1062–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong T, Hofer SOP, McCready DR, Jacks LM, Cook FE, Baxter N. A comparison of surgical complications between immediate breast reconstruction and mastectomy: the impact on delivery of chemotherapy-an analysis of 391 procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:560–566. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanzel KR, Brown MH, Anastakis DJ, Regehr G. Reconstructive breast surgery: referring physician knowledge and learning needs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(6):1441–1450. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cold S, During M, Ewertz M, Knoop A, Moller S. Does timing of adjuvant chemotherapy influence the prognosis after early breast cancer? Results of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) Br J Cancer. 2005;93(6):627–632. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colleoni M, Bonetti M, Coates AS, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Price K, et al. Early start of adjuvant chemotherapy may improve treatment outcome for premenopausal breast cancer patients with tumors not expressing estrogen receptors. The International Breast Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(3):584–690. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jara Sanchez C, Ruiz A, Martin M, Anton A, Munarriz B, Plazaola A, et al. Influence of timing of initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy over survival in breast cancer: a negative outcome study by the Spanish Breast Cancer Research Group (GEICAM) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101(2):215–223. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lohrisch C, Paltiel C, Gelmon K, Speers C, Taylor S, Barnett J, et al. Impact on survival of time from definitive surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4888–4894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon C, Ashley S, Smith IE. Does timing of adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer influence survival? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3792–3797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatala R, Keitz S, Wyer P, Guyatt G, Evidence-Based Medicine Teaching Tips Working G (2005) Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 4. Assessing heterogeneity of primary studies in systematic reviews and whether to combine their results. CMAJ 172 (5):661–665. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Alderman AK, Collins ED, Schott A, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Theriault RL, et al. The impact of breast reconstruction on the delivery of chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:1791–1800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allweis TM, Boisvert ME, Otero SE, Perry DJ, Dubin NH, Priebat DA. Immediate reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer does not prolong the time to starting adjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:218–221. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang RJC, Kirkpatrick K, De Boer RH, Bruce Mann G. Does immediate breast reconstruction compromise the delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy? Breast. 2013;22:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksen C, Frisell J, Wickman M, Lidbrink E, Krawiec K, Sandelin K. Immediate reconstruction with implants in women with invasive breast cancer does not affect oncological safety in a matched cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:439–446. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1437-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamahata A, Kubo K, Takei H, Saitou T, Hayashi Y, Matsumoto H, et al. Impact of immediate breast reconstruction on postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy: a single center study. Breast Cancer. 2013;22:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn J, Barrett S, Forte C, Stallard S, Weiler-Mithoff E, Doughty JC, et al. Oncoplastic breast conservation does not lead to a delay in the commencement of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(8):887–891. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Lee SK, Kim S, Koo MY, Choi MY, Bae SY, et al. Does immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy affect the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy? J Breast Cancer. 2011;14:322–327. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2011.14.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortenson MM, Schneider PD, Khatri VP, Stevenson TR, Whetzel TP, Sommerhaug EJ, et al. Immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy increases wound complications: however, initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy is not delayed. Arch Surg. 2004;139:988–991. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.9.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman LA, Kuerer HM, Hunt KK, Ames FC, Ross MI, Theriault R, et al. Feasibility of immediate breast reconstruction for locally advanced breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:671–675. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rey P, Martinelli G, Petit JY, Youssef O, De Lorenzi F, Rietjens M, et al. Immediate breast reconstruction and high-dose chemotherapy. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:250–254. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000174762.36678.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor CW, Kumar S. The effect of immediate breast reconstruction on adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast. 2005;14:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandergrift JL, Niland JC, Theriault RL, Edge SB, Wong YN, Loftus LS, et al. Time to adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer in National Comprehensive Cancer Network institutions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:104–112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson CR, Brown IM, Weiller-Mithoff E, George WD, Doughty JC. Immediate breast reconstruction does not lead to a delay in the delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:624–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller ME, Czechura T, Martz B, Hall ME, Pesce C, Jaskowiak N, et al. Operative risks associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a single institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(13):4113–4120. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barry M, Kell MR. Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song J, Zhang X, Liu Q, Peng J, Liang X, Shen Y, et al. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on immediate breast reconstruction: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh E, Chim H, Soltanian HT. The effects of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy on the surgical outcomes of breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(10):e267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gieni M, Avram R, Dickson L, Farrokhyar F, Lovrics P, Faidi S, et al. Local breast cancer recurrence after mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction for invasive cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast. 2012;21(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.