Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress leads to activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling cascade and induction of an apoptotic cell death, autophagy, oncogenesis, metastasis, and/or resistance to cancer therapies. Mechanisms underlying regulation of ER transmembrane proteins PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6α/β, and how the balance of these activities determines outcome of the activated UPR, remain largely unclear. Here, we report a novel molecule transmembrane protein 33 (TMEM33) and its actions in UPR signaling. Immunoblotting and northern blot hybridization assays were used to determine the effects of ER stress on TMEM33 expression levels in various cell lines. Transient transfections, immunofluorescence, subcellular fractionation, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting were used to study the subcellular localization of TMEM33, the binding partners of TMEM33, and the expression of downstream effectors of PERK and IRE1α. Our data demonstrate that TMEM33 is a unique ER stress-inducible and ER transmembrane molecule, and a new binding partner of PERK. Exogenous expression of TMEM33 led to increased expression of p-eIF2α and p-IRE1α and their known downstream effectors, ATF4-CHOP and XBP1-S, respectively, in breast cancer cells. TMEM33 overexpression also correlated with increased expression of apoptotic signals including cleaved caspase-7 and cleaved PARP, and an autophagosome protein LC3II, and reduced expression of the autophagy marker p62. TMEM33 is a novel regulator of the PERK-eIE2α-ATF4 and IRE1-XBP1 axes of the UPR signaling. Therefore, TMEM33 may function as a determinant of the ER stress-responsive events in cancer cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10549-015-3536-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: TMEM33, Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response, PERK, IRE1α, Caspase-7, Autophagy, Breast cancer

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is involved in several fundamental cellular processes including synthesis and sorting of secretory and membrane proteins, detoxification, and intracellular calcium homeostasis [1]. Correct folding of proteins in the ER lumen is regulated by folding and oxidizing enzymes in the presence of chaperones and glycosylating enzymes dependent on ATP and high Ca2+ levels. Misfolded proteins are exported to the cytoplasm for proteosomal degradation by a process known as the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [2]. ER stress, as defined by the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins above the threshold levels in the ER lumen, leads to activation of an ER-to-nucleus unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling cascade. The ER transmembrane proteins protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6α/β) sense ER stress, each then regulating one of the three distinct axes of the UPR signaling cascade [3]. ER stress-activated PERK phosphorylates serine 51 of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), followed by the suppression of protein synthesis and a selective increase in ATF4 activity. Downstream effectors of PERK signaling include both pro-survival factors such as the transcription factor NRF2 and microRNA miR-211, which are associated with adaptation response, and pro-apoptotic factors including CHOP that can induce cell death [4, 5]. Stress-induced phosphorylation and activation of IRE1α results in activation of the transcription factor X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) and increased expression of ER chaperones such as GRP78/BiP which, in turn, increase protein folding capacity in the ER lumen. Activated IRE1α also reduces protein load in the ER lumen by cleaving mRNAs encoding secretory and membrane proteins through regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD). In the ATF6α/β arm of the UPR signaling, ATF6α/β is transported to the golgi where it undergoes cleavage; cleaved ATF6 (ATF6f/ATF6c) functions as a transcription factor for several ER chaperones.

Mechanisms underlying regulation of PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6α/β, and how the balance of these activities determine outcome of the activated UPR, remain largely unclear. Indeed, depending on the acute or chronic ER stress and cellular context, activation of the UPR may lead to apoptotic cell death, senescence, autophagy, oncogenesis, metastasis, and/or resistance to chemotherapeutics and endocrines [6–14]. Identification of new molecules regulating UPR signals may advance understanding of the mechanistic and functional significance of UPR in cancer biology and therapy.

Here, we report characterization of transmembrane protein 33, TMEM33 (also known as SHINC-3) as a novel ER stress-inducible and ER transmembrane molecule and regulator of two main drivers of the UPR: PERK and IRE1α. Our data show that TMEM33 is a new binding partner of PERK. TMEM33 overexpression led to increased expression levels of both p-eIF2α and p-IRE1α and of their respective downstream effectors, ATF4 and XBP1-S in breast cancer cells. TMEM33 overexpression also led to increased expression of CHOP, cleaved caspase-7, and the autophagosome marker LC3II in these cells. Collectively, this work provides new mechanistic insights into the regulation of PERK and IRE1α signaling pathways via TMEM33 in cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Antibodies, reagents, and chemicals

Rabbit polyclonal antibody was custom generated against a TMEM33-specific peptide, KKVLDARGSNSLPLLR (amino acids 127–143; Covance Research Products Inc., Denver, PA). Polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (2275-PC-1) was purchased from Trevigen (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (TU-02), monoclonal anti-Myc antibody (9E10), monoclonal horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-cMyc antibody (9E10HRP), polyclonal anti-PERK antibody (H-300), polyclonal anti-GRP78/BiP antibody (C-20), polyclonal anti-IRE1 antibody (H-190), polyclonal anti-Calnexin antibody (C-20), monoclonal anti-PARP antibody (F-2), polyclonal anti-ATF4 antibody (H-290), polyclonal anti-ATF-6α antibody (H-280), monoclonal anti-Cyclin D1 antibody (sc-20044); polyclonal anti-β-actin antibody (sc-1616) and Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose immunoprecipitation reagent were all purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Monoclonal anti-COX4 antibody (12C4) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Monoclonal anti-Myc antibody (2276), monoclonal anti-PERK antibody (5683), polyclonal anti-phospho-eIF2α (Ser51) antibody (9721), polyclonal anti-eIF2α antibody (9722), monoclonal anti-phospho-eIF2α antibody (3597), monoclonal anti-ATF4 antibody (11815), monoclonal anti-LC3II antibody (12741), monoclonal anti-CHOP antibody (2895), polyclonal anti-cleaved-caspase-7 antibody (9491), polyclonal anti-caspase-7 antibody, and polyclonal anti-cleaved PARP antibody were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). Additional antibodies and reagents used were as follows: monoclonal anti-ATF6 antibody (IMG-273, Imagnex); polyclonal anti-XBP1 antibody (GWB-BACB31, Genway); polyclonal anti-phospho-IRE1α antibody (PA1-16927, Thermoscientific); monoclonal anti-p62 antibody (610832, BD-Bioscience); FITC-conjugated monoclonal anti-Calnexin antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories); horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse and rabbit secondary antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA); Lipofectamine 2000, Lipofectamine LTX, and Lipofectin (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA); Fu Gene HD (Roche); proteinase inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA); ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences); Coomassie protein assay reagent and Surfact-Amps NP-40 (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA); Tween 20 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules,CA, USA); Re-Blot plus mild antibody stripping solution (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA, USA); Restore Western blot stripping buffer (21059, ThermoScientific), and thapsigargin, tunicamycin from Streptomyces sp., dimethyl sulphoxide Hybri-Max Sterile filtered (DMSO), and etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell lines and cultures

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and Tissue Culture Shared Resource of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. HEK293T human embryonic kidney cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). Human prostate cancer cells (PC-3 and DU-145), breast cancer cells (MDA-MB231), HeLa, and COS-1 cells were obtained from the Tissue Culture Shared Resource of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. All cell lines were grown as monolayers in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 5 or 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Endocrine-sensitive (LCC1) and endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells (LCC9), and antiestrogen-resistant MCF-7 cells (MCF7RR) were obtained and established as reported earlier [15–17]. LCC1, LCC9, and MCF7RR cells were maintained in IMEM without phenol red and supplemented with 5 % charcoal-stripped calf serum (CCS). All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C under 95 % relative humidity and 95 % O2:5 % CO2 atmosphere.

Construction of Myc-TMEM33 expression vector

TMEM33 cDNA (741 bp) was amplified by RT-PCR using total mRNA from human testes (Ambion, Foster City, CA) and cloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen). N-terminal Myc-tagged TMEM33 ORF (771 bp) was amplified by PCR using TMEM33 in pCR2.1 as template. The forward primer sequence containing the translation initiation codon, the Myc epitope (underlined), and Bgl II primer (bold) was 5′-GAGATCTGCCATGGAGCAGAAACTCATCTCTGAAGAGGACCTGATGGCAGATACGACCCCGAAC-3′, and the reverse primer sequence containing the MulI primer (bold) was 5′-GACGCGTCTATGGAACTGTTGGTGCC -3′ as described earlier [18]. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 4 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s; annealing at 65 °C for 1 min; extension at 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The amplified product was subjected to electrophoresis in 1 % agarose gels and cloned into the pCR3.1 expression vector. TMEM33 cDNA sequence was verified by automated DNA sequencing of both strands using vector-based forward and reverse primers as detailed earlier [18, 19].

Transient cDNA transfections

COS-1, HEK-293T, and PC-3 prostate cancer cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HeLa cells were transiently transfected using FuGene HD (Roche), and MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 breast cancer cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Immunofluorescence and immunostaining

COS-1 cells were grown overnight on coverslips placed in a six well plate, one coverslip/well. Approximately, 3 × 104 cells were seeded/well. Next day, cells were transfected with 1 µg of Myc-TMEM33 or empty vector using Lipofectamine 2000. Forty eight hours post-transfection, the medium was removed and cells were immediately fixed in 3.7 % paraformaldehyde, followed by immunofluorescence and immunostaining using various antibodies as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Subcellular fractionation

Approximately, 5 × 106 MCF-7 cells were seeded per 150 mm tissue culture dish. Next day, the cells were collected by trypsinization and washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cytosolic, mitochondrial (heavy membrane), microsomal (light membrane), and nuclear fractions were isolated as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

The whole cell lysate (approximately 2 mg protein) was incubated with 25 μL of agarose-conjugated anti-Myc antibody on a rotator at 4 °C overnight. The antibody-conjugated agarose beads were washed 1x in cell lysis buffer and used for immunoblotting as reported earlier [20] and detailed in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Thapsigargin and tunicamycin treatments

Stock solutions of thapsigargin (TG, 2 mM) and tunicamycin (TU, 2 mg/mL) were made in DMSO and stored at −20 °C. Cells from approximately 80 % confluent monolayers were used. The culture medium was removed and fresh DMEM containing 10 % FBS and the desired final concentration of TG or TU was added to the cells and incubation continued for various periods, followed by cell lysis and Western blotting as described in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Results

TMEM33 is a novel endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane protein

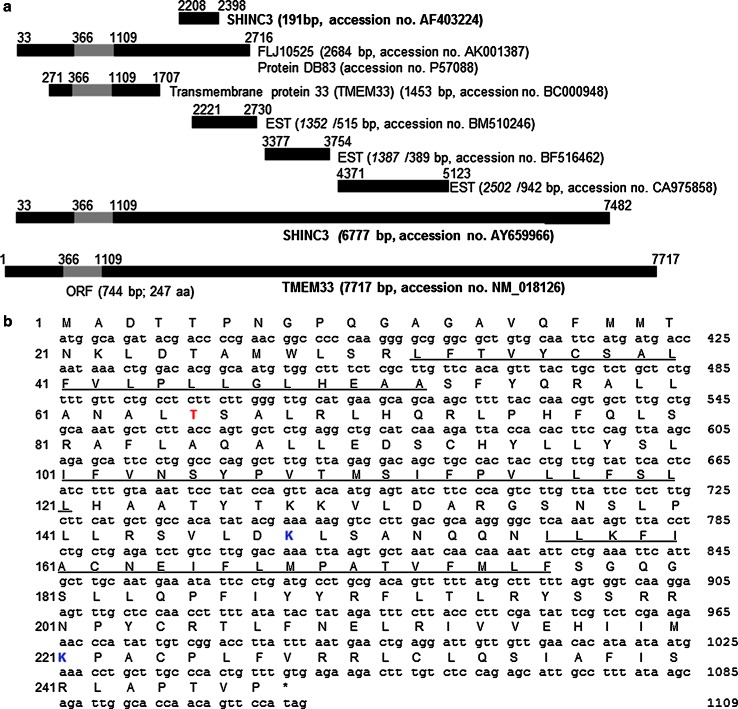

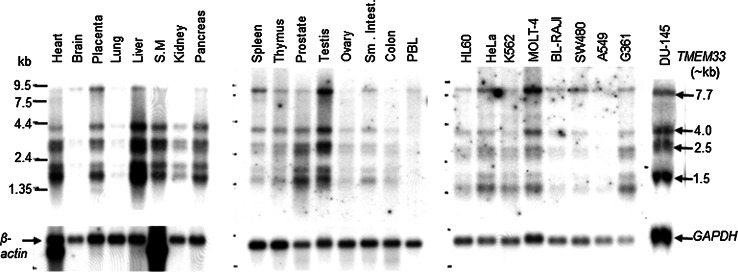

We identified TMEM33 as a novel cDNA fragment (191 bp) in a differentially displayed mRNA screen of cancer cells treated with antisense raf oligonucleotide or control mismatch oligonucleotide [GenBank accession number AF403224]. Subsequent sequential homology search of the human expressed sequence tag (EST) database [21] led to identification of the full-length TMEM33 cDNA sequence (7717 bp) as shown in Fig. 1a. The longest open reading frame of the full-length TMEM33 cDNA encodes a new 247 amino acids (aa) protein (approximately 28 kDa Mr) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1). The TMEM33 amino acid sequence revealed three transmembrane helices (32–52 aa, 101–121 aa, and 156–176 aa), at least one phosphorylation site (T65) and two ubiquitination sites (K148 and K221) [22–24] (Fig. 1b). Using northern hybridization, four major TMEM33 transcripts (7.7, 4.0, 2.5, and 1.5 kb) were detected in most normal human tissues and cancer cell lines tested (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Schematic maps of TMEM33 cDNA, and predicted open reading frame and amino acid sequence of TMEM33. a Maps of the complete human TMEM33 (alias SHINC3) cDNA and overlapping partial clones are shown. The gray box represents the coding region and the black boxes represent the 5′- and 3′- untranslated regions of the cDNA sequence. Italicized numbers represent the original lengths of the overlapping clones in the GenBank database. The NCBI BLAST program [43] was used to identify the overlapping sequences and deduce the full-length sequence of TMEM33 cDNA. b Predicted open reading frame (366–1109 bp) and amino acid sequence alignment of TMEM33 protein (247 aa). Locations of three transmembrane helices (32–52 aa, 101–121 aa, and 156–176 aa, underlined), a phosphorylation site (T65, red) and two ubiquitination sites (K148 and K221, blue) are shown

Fig. 2.

Expression analyses of TMEM33 transcripts in normal human tissues and human cancer cell lines. The mRNA blots (Clontech) were sequentially probed with a radiolabeled TMEM33 cDNA probe, followed by β-actin or GAPDH cDNA probe. S.M., smooth muscle; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes; HL-60, promyelogenous leukemia; K-562, chronic myelogenous leukemia; MOLT-4, lymphoblastic leukemia; BL-Raji, Burkitt’s lymphoma; SW480, colorectal adenocarcinoma; A549, lung carcinoma; G361, melanoma; DU-145, prostate cancer

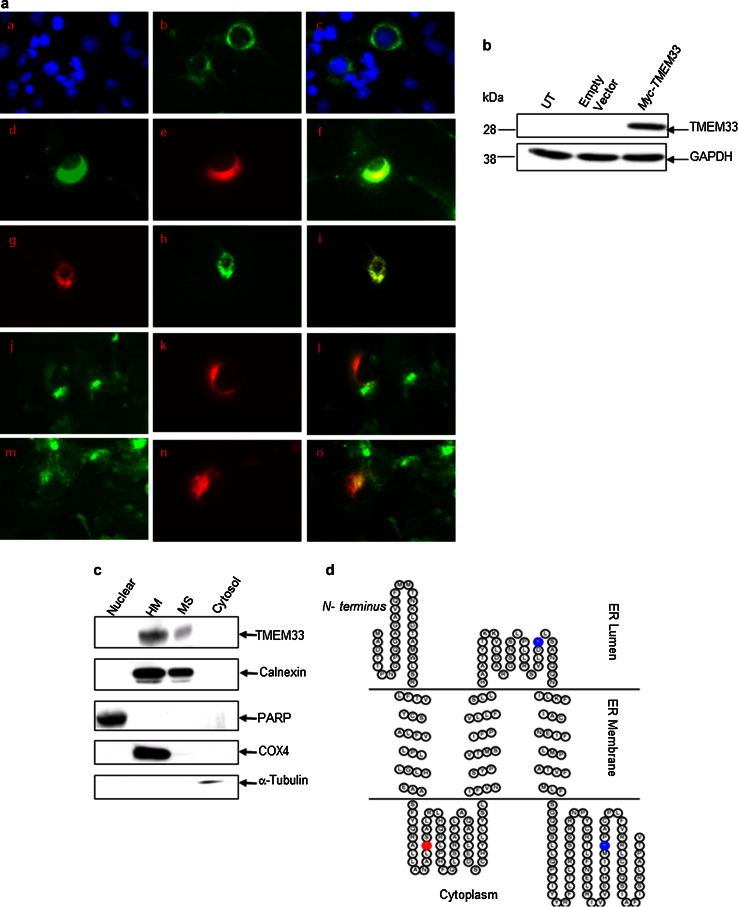

Based on prediction of its likely subcellular localization, the TMEM33 protein appeared to be localized to ER [25]. Subcellular localization of TMEM33 was demonstrated using a combination of immunofluorescence and biochemical fractionation analyses. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with either a Myc epitope-tagged TMEM33 expression vector (Myc-TMEM33) or empty vector. Immunofluorescence staining showed co-localization of Myc-TMEM33 with Calnexin and ER-tracker but not mito-tracker or WGA staining (Fig. 3a). Expression of Myc-TMEM33 in COS-1 transfectants was verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

TMEM33 is an ER transmembrane resident protein. a Immunofluorescence analysis of ER localization of TMEM33 in COS-1 transfectants. After 48 h of transfection with Myc-TMEM33 cDNA expression vector, COS-1 transfectants were fixed and immunostained as described in “Materials and methods” section. For ER-tracker or Mito-tracker staining, transfected cells were first incubated with these dyes. Right subpanels: a DAPI; d anti- Calnexin antibody; g ER-tracker; j Mito-tracker; m, WGA. Middle subpanels (b, e, h, k, n): anti-Myc antibody. Left panels (c, f, i, l, o): merge of corresponding right and middle panels. b Expression of Myc-TMEM33 protein in transiently transfected COS-1 cells was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. The blot was reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody. UT untransfected. c The subcellular localization of endogenous TMEM33. MCF-7 cells were homogenized and fractionated into nuclear, heavy membrane (HM), microsomal (MS), and cytosolic fractions, followed by sequentially immunoblotting of the cell fractions using anti-TMEM33, anti-Calnexin (ER membrane), anti-PARP (nucleus), anti-COX4 (mitochondria), and anti-tubulin (cytosol) antibodies. WCE, whole cell extract. d The ER membrane structure of TMEM33. TOPO2, transmembrane protein display software, was used to display 2D topology of TMEM33. ER lumen, N-terminus 1–31 aa; 122–155 aa; ER membrane, 32–52 aa; 101–121 aa; 156–176 aa; Cytoplasm, 53–100 aa; 177–247 aa—C terminus; Potential phosphorylation site (T65) (red) and two ubiquitination sites (K148 and K221) (blue) are shown

Subcellular localization of the endogenous TMEM33 protein was examined by cell fractionation and immunoblotting using a custom-generated rabbit polyclonal antibody against a TMEM33-specific epitope (aa 127–143). The anti-TMEM33 antibody recognized an approximately 28 kDa protein in human prostate cancer cells (PC-3 and DU-145); pre-immune serum had no immune reactivity at the corresponding location (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The anti-TMEM33 antibody was further validated by sequential immunoblotting of cell lysates from COS-1 Myc-TMEM33 transfectants with anti-Myc and anti-TMEM33 antibodies. These two antibodies recognized an overlapping band at ~28 kDa in COS-1 transfectants (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Using the custom-generated anti-TMEM33 antibody, human endogenous TMEM33 (~28 kDa) was detected in several human cancer cell lines including A549, Aspc-1, Colo-357, MDA-MB435, MCF-7, and HeLa cells (data not shown). In the combined cell fractionation and immunoblotting assay, Calnexin was detected in both the heavy membrane pellet (HM) and the ER-containing microsomal fractions (MS) of MCF-7 cells; heavy membrane pellets contain mitochondrial, lysosomal, and ER-resident proteins. Similar to Calnexin, endogenous TMEM33 expression was seen in both the HM and MS fractions of MCF-7 cells but not in the nuclear or cytosolic fractions (Fig. 3c). Together with the predicted 2D topology of TMEM33 [26, 27] (Fig. 3d) these data establish TMEM33 as a novel ER transmembrane resident protein.

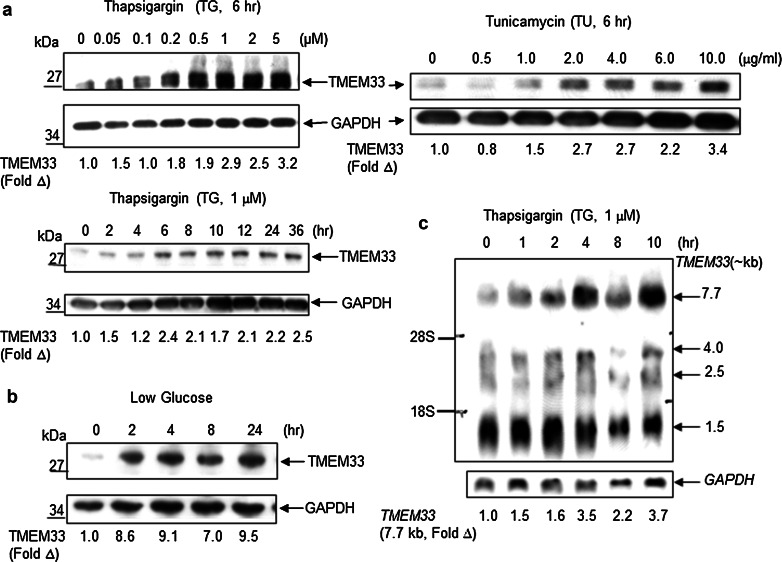

TMEM33 is an ER stress-inducible molecule

The ER localization of TMEM33 prompted us to ask whether TMEM33 expression is stimulated in response to known inducers of ER stress including thapsigargin (TG), an inhibitor of ER Ca2+ ATPase, tunicamycin (TU), an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation, and low glucose. Expression of TMEM33 was analyzed in HeLa cells exposed to TG, TU or low glucose. TMEM33 protein expression was increased in response to ER stress (Fig. 4a, b). Consistent with these observations, a significant induction of the largest TMEM33 transcript (7.7 kb) was seen in HeLa cells treated with thapsigargin (Fig. 4c). As expected, GRP78/BiP, a well-known ER stress-inducible protein chaperone in the ER lumen, was also induced in HeLa cells under similar conditions (data not shown). In addition, ER stress-inducible expression of TMEM33 and GRP78/BiP was also noted in PC-3 prostate cancer cells (data not shown). Thus, TMEM33 is a new ER stress-inducible protein.

Fig. 4.

TMEM33 is an ER stress-inducible molecule. a HeLa cells were treated with indicated doses of thapsigargin (TG) or tunicamycin (TU) for various times, followed by immunoblotting with anti-TMEM33 antibody. The blots were reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody. The expression levels of TMEM33 were quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics), and normalized against GAPDH in corresponding lanes. The fold open triangle indicates TMEM33 level at various doses or time points relative to control lane. Data shown are representative of two to three independent experiments. b HeLa cells were grown in high glucose (25 mM) DMEM containing 10 % FBS. The medium was switched to low glucose (5.5 mM) DMEM containing 10 % FBS for the times indicated, followed by sequential immunoblotting with anti-TMEM33 antibody and anti-GAPDH antibody. Normalized expression levels of TMEM33 were quantified as in panel a. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. c Northern blot analysis of TMEM33 mRNA in HeLa cells treated with thapsigargin as shown. The blot was reprobed with radiolabeled GAPDH cDNA. The normalized expression levels of 7.7 kb TMEM33 transcript at various time points were quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics)

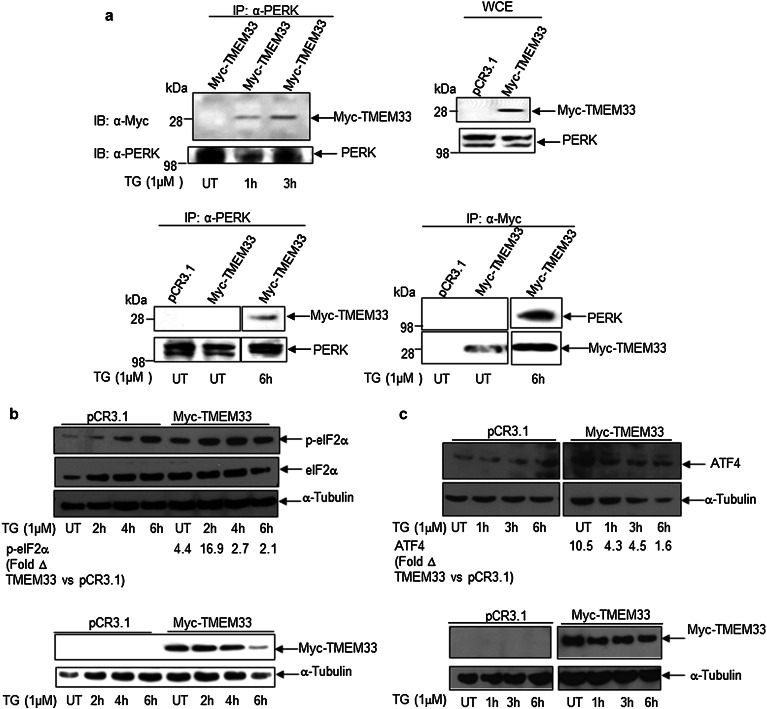

TMEM33 overexpression is associated with enhanced stimulation of the ER stress-responsive PERK/p-eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway

To determine whether TMEM33 is a component of the ER stress-inducible UPR signaling pathway, we first looked for interaction(s) between TMEM33 and the ER membrane-resident molecules PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the Myc-TMEM33 plasmid and treated with 1 µM TG for various times. Using a reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation assay, our findings show an ER stress-related interaction between TMEM33 and PERK (Fig. 5a). Myc-TMEM33 did not interact with either IRE1α or ATF6 under similar conditions (data not shown). Next, we examined the effects of TMEM33 overexpression on downstream effectors of activated PERK (p-eIF2α; ATF4). As shown in Fig. 5b and c, and Supplementary Fig. 3, overexpression of TMEM33 was associated with enhanced basal and ER stress-induced expression of p-eIF2α and ATF4 in Myc-TMEM33 transfectants, relative to empty vector control transfected HEK293T cells. These data establish TMEM33 as a novel binding partner of PERK and demonstrate that TMEM33 overexpression correlates with enhanced activation of the ER stress-inducible PERK/p-eIF2α/ATF4 signaling.

Fig. 5.

TMEM33 is a binding partner of PERK and TMEM33 overexpression correlates with increased levels of basal and ER stress- induced p-elF2α and ATF4 expression. a TMEM33 interacts with PERK in the presence of ER stress. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with Myc-TMEM33 for 48 h at 37 °C, followed by treatment with 1 µM TG for the times indicated. The whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-Myc antibody or anti-PERK antibody-conjugated Protein A/G and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting as indicated. Representative data from two independent experiments are shown. IP immunoprecipitation; IB immunoblotting; WCE whole cell extracts. UT untreated. b Increased basal and ER stress-induced expression of p-eIF2α in Myc-TMEM33 transfected HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with Myc-TMEM33 or pCR3.1 (empty vector) and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, followed by treatment with 1 μM TG as indicated. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-p-eIF2α antibody. Blots were reprobed with anti- eIF2α and anti-α-Tubulin antibodies (top panel). Cell lysates were also probed with anti-Myc and anti-α-Tubulin antibodies (bottom panel). For quantification of relative p-eIF2α levels in Myc-TMEM transfectants versus control vector at various time points, first total eIF2α levels were normalized against α-Tubulin in corresponding lanes. Expression levels of p-eIF2α were then normalized against α-Tubulin-normalized eIF2α levels in corresponding lanes. The fold Δ in p-eIF2α level was calculated by dividing normalized p-eIF2α level in Myc-TMEM transfectants by normalized p-eIF2α level in pCR3.1 transfectants in the corresponding treatment group. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. UT, untreated. c Increased expression of ATF4 in Myc-TMEM33 transfected HEK293T cells. Whole cell extracts of empty vector (pCR3.1) or Myc-TMEM33 transfected cells were prepared after thapsigargin treatment (TG) as described in Materials and methods. Cell lysates were sequentially immunoblotted with anti-ATF4 and anti-α-Tubulin antibodies (top panel). Cell lysates were also probed with anti-Myc and anti-α-Tubulin antibodies (bottom panel). For quantification of relative ATF4 levels in Myc-TMEM33 transfectants versus control vector at various time points, expression levels of ATF4 were normalized against α-Tubulin in corresponding lanes. The fold Δ in ATF4 level was calculated by dividing normalized ATF4 level in Myc-TMEM33 transfectants by normalized ATF4 level in pCR3.1 transfectants in the corresponding treatment group. Representative data from two independent experiments are shown. UT untreated

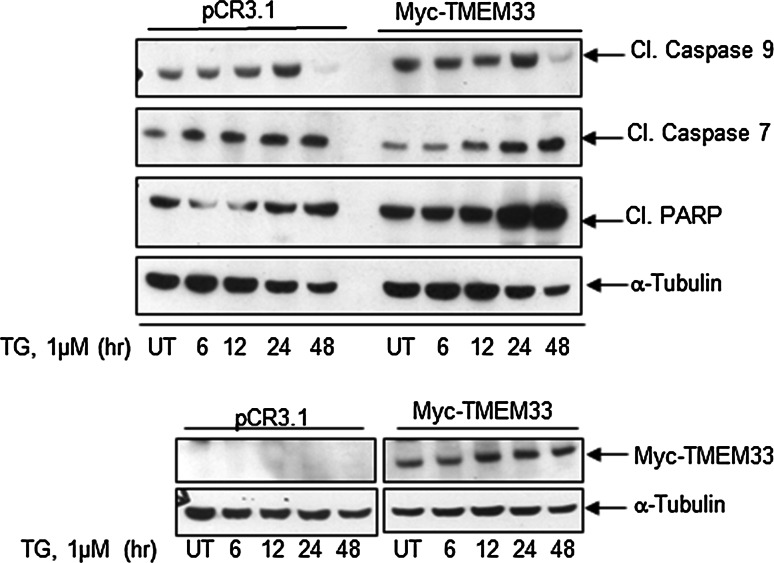

TMEM33 overexpression and increased expression of ER stress-induced cell death signals

We next determined the effects of TMEM33 overexpression on various cell death signals. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with a Myc-TMEM33 or control vector and exposed to TG (1 µM) for indicated times, followed by immunoblotting of whole cell lysates with various antibodies (Fig. 6). For quantification of relative levels of cleaved caspase 9, cleaved caspase 7 and cleaved PARP in Myc-TMEM33 transfectants versus control vector, expression levels were first normalized against α-Tubulin in corresponding lanes. The fold Δ in relative expression level in Myc-TMEM33 cells was calculated by dividing normalized value in Myc-TMEM 33 transfectants by normalized value in pCR3.1 transfectants in the corresponding treatment group. Basal levels of cleaved caspase 9 were found to be higher in Myc-TMEM33 transfected HeLa cells relative to control vector transfectants (Myc-TMEM33 versus pCR3.1, Cl. Caspase 9, untreated (UT), 1.8 fold). Increased expression levels of cleaved caspase 7 and cleaved PARP were observed in Myc-TMEM33 transfectant HeLa cells following TG treatment relative to control vector transfectants (Myc-TMEM33 versus pCR3.1: Cl. Caspase 7, TG (1 µM, 48 h), 5.0 fold; Cl. PARP, TG (1 µM, 48 h), 3.0 fold). Increased expression levels of cleaved Caspase 7 and cleaved PARP were also observed following TG treatment of COS-1 cells transiently transfected with Myc-TMEM33 versus control vector transfectants (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In addition, Caspase 2 expression was found to be increased in Myc-TMEM33 transfectant COS-1 cells versus control transfectants (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Interestingly, expression of cleaved caspase 3 did not seem to change in these cells (data not shown). Furthermore, constitutive expression of cleaved caspase 7 was also seen in TMEM33-transfected MCF-7 breast cancer cells but not in control pCR3.1-transfected cells (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Fig. 6.

TMEM33 overexpression is associated with increased ER stress-inducible expression of cleaved caspase 7 and cleaved PARP. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with Myc-TMEM33 or pCR3.1 (empty vector) and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, followed by treatment with 1 μM TG for indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting for expression of pro-apoptotic signals. Blots were reprobed with anti-α-Tubulin antibody (top panel). Cell lysates were also probed with anti-Myc and anti-α-Tubulin antibodies (bottom panel). UT untreated

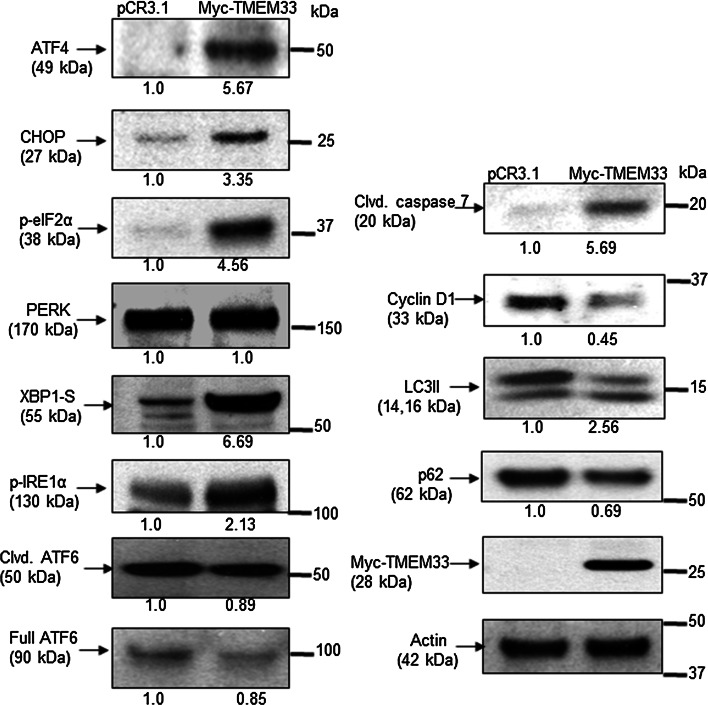

Fig. 7.

Exogenous expression of TMEM33 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells is associated with constitutive activation of the PERK and IRE1α axes of the UPR signaling. MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with Myc-TMEM33 or pCR3.1 control vector. Adherent and floating cells were collected 24 h post-transfection. Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor (Roche), 10 mM glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM pyrophosphate, and 1 mM PMSF. Cell lysates (10 μg protein) were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies (all 1:1000 dilution)

TMEM33 overexpression and constitutive activation of the PERK-p-elF1α-ATF4 and IRE1α-XBP1 axes of the UPR signaling and autophagy in breast cancer cells

To address the consequences of TMEM33 overexpression in human cancer cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells were transiently transfected with either the Myc-TMEM33 or pCR3.1 vector, followed by immunoblotting of the cell lysates with antibodies against various components of the UPR signaling pathways. Figure 7 shows that exogenous expression of TMEM33 was sufficient to increase basal levels of p-eIF2α, ATF4, CHOP, cleaved caspase 7, p-IRE1α, and XBP1-S but not cleaved ATF6. In addition, cyclin D1 expression, a marker of cell cycle progression and oncogenesis, was decreased in Myc-TMEM33 transfectant MCF-7 cells. The latter observations seem to be inconsistent with data showing high TMEM33 expression in several tumor tissues including breast cancer (Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, TMEM33 is reported to be amplified in approximately 10 % of breast cancer patient xenografts [28–30]. During autophagy, microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3 (LC3I) is converted to its membrane-bound form (LC3II). We have previously reported that overexpression of XBP1 can regulate autophagy through its control of BCL2 [31–33]. Increased expression of LC3II and decreased expression of p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1), ubiquitin-binding protein and promoter of apoptosis, was detected in Myc-TMEM33 transfected MCF-7 cells relative to controls (Fig. 7). Similar observations were made in hormone refractory MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). Hence, TMEM33 overexpression is associated with constitutive activation of PERK-p-elF1α-ATF4 and IRE1α-XBP1-S signaling and autophagy in breast cancer cells.

Discussion

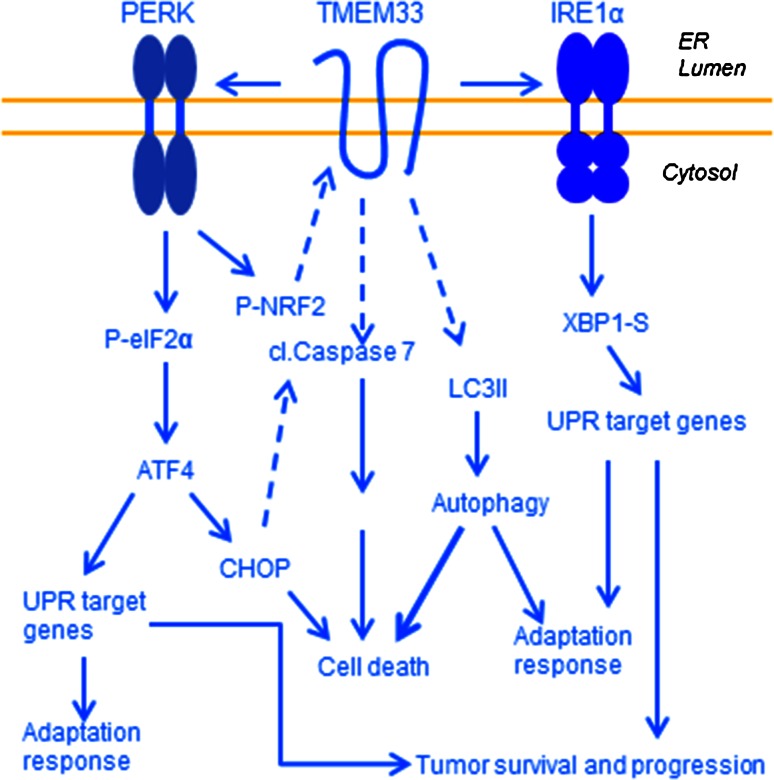

This study is the first report of TMEM33 as a new ER stress-inducible and ER transmembrane resident molecule. PERK and IRE1α axes of the UPR play prominent roles in regulation of adaptation and cell death signals, yet how these two receptors are regulated remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate: (1) TMEM33 is a novel binding partner of PERK and that TMEM33 overexpression correlates with increased expression of downstream effectors of PERK, p-eIF2α, and ATF4, and cleaved caspase 7 in cells challenged with thapsigargin, (2) association of enhanced expression of TMEM33 with increases in components of the activated PERK and IRE1α signaling pathways (p-eIF2α, ATF4, CHOP, cleaved caspase 7, XBP1-S) in breast cancer cells, and (3) association of enhanced expression of TMEM33 with increased autophagy in breast cancer cells. Autophagy has been associated with tumor cell resistance to various therapies. In pilot studies, we also tested whether TMEM33 may serve as a new prognostic marker in certain estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Gene expression microarrays were used to measure TMEM33 expression in endocrine-resistant (LCC9, MCF7RR) and sensitive breast cancer cells (LCC1 and MCF7) [15–17], and in clinical specimens [34–37]. TMEM33 mRNA expression was found to be higher in endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells as compared with their matched sensitive control cells. In addition, early recurrent breast cancer specimens showed high TMEM33 expression when compared with non-recurrent breast tumors (Supplementary Fig. 7). Taken together, our current observations suggest a working model where TMEM33 may function as a critical determinant of the balance between PERK and IRE1α-mediated apoptotic, adaptive and neoplastic transformation events in cancer cells (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Proposed model of a role of TMEM33 in regulation of the PERK and IRE1α axes of the unfolded protein response signaling. ER stress leads to increased expression of TMEM33 and activation of PERK resulting in enhanced levels of p-eIF2α and ATF4. Depending of the cell type, overexpression of TMEM33 may also increase expression of p-IRE1α and its effector XBP1-S. Additional downstream effectors include increased expression of CHOP, cleaved caspase-7, cleaved PARP, and autophagosome marker LC3II, and reduced expression of p62. Dashed arrows indicate as yet unknown pathways

How TMEM33 expression is regulated remains unknown. The proximal promoter region of the TMEM33 gene shows putative binding site for NRF-2, a prosurvival transcription factor downstream of the activated PERK (Supplementary Fig. 1c). It is tempting to speculate that an as yet unknown combination of feedback and cross-talk exists. For example, where ER stress activates PERK and increases TMEM33 expression via NRF-2, and increased TMEM33 overexpression, depending on the cell type, promotes PERK and IRE-1α activated signaling. TMEM33 may also interact with other proteins. At least one phosphorylation site (Thr 65) and two ubiquitination sites (Lys 148 and Lys 221) are predicted within the open reading frame of TMEM33 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). TMEM33 may be a member of the family of ubiquitin-modified proteins [38–40]. The STRING database [41] also predicts potential interaction of TMEM33 with ubiquitin C (UBC), and ubiquitin specific peptidase 19 (USP19), associated with ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (Supplementary Fig. 8). TMEM33 may also interact with the retention in endoplasmic reticulum 1 protein (RER1), which is involved in the retrieval of ER membrane proteins from the early golgi compartment (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Present report supports the hypothesis that TMEM33 may function as a multi-faceted molecule in cancer cells. While our data suggest that TMEM33 overexpression correlates with enhanced expression of apoptotic signals (CHOP and cleaved caspase7), constitutive expression of TMEM33 was found to be high in a limited number of endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells and in early recurrent breast cancer specimens tested. The latter observations are consistent with the roles of PERK and ATF4 in tumor cell survival [42]. Moreover, autophagy may increase survival of tumor cells [8, 9]. We observed increased expression of autophagosome marker LC3II and downregulation of p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) in breast cancer cells overexpressing TMEM33, suggesting induction and completion of autophagy. In conclusion, TMEM33 offers a new regulatory mechanism of the UPR and may serve as a determinant of the outcome of activated UPR signaling cascade.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sona Vasudevan for analysis of TMEM33 profiles in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and cBioPortal databases. This work was funded by NIH Grants CA68322, CA74175, CA149147, and CA184902 and NeoPharm, Inc. Several cell lines were obtained from the Tissue Culture Shared Resource of the Georgetown Lombardi Cancer Center. The RNA array expression profiling was performed at the Genomics and Epigenomics Shared Resource and the immunofluorescence imaging was performed at the Microscopy & Imaging Shared Resource of the Georgetown Lombardi Cancer Center. All shared resources were supported by the NIH Grant P30-CA51008.

Abbreviations

- ATF4

Activating transcription factor 4

- ATF6

Activating transcription factor 6

- ATF6f/c

Cytosolic domain of ATF6

- CHOP

C/EBP(CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein) homologous protein

- eIF2α

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- GRP78/BiP

Glucose-regulated protein 78

- IRE1α

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α

- LC3II

Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

- PERK

Protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase

- TG

Thapsigargin

- TMEM33

Transmembrane protein 33

- TN

Tunicamycin

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- XBP1

X-box binding protein 1

- XBP1-S

Active (spliced) XBP1

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

TMEM33 (alias SHINC-3) is a Georgetown University patented technology, “Gene SHINC-3 and Diagnostic and Therapeutic Uses Thereof,” US Patent # 7244565. IS and UK are co-inventors of this technology. RH, LJ and RC declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors declare that all experiments reported in this manuscript were performed in compliance with all current laws and regulations of the United States of America.

References

- 1.Braakman I, Bulleid NJ. Protein folding and modification in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Ann Rev Biochem. 2011;80:71–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062209-093836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodsky JL. ERAD-cleaning up: ER-associated degradation to the rescue. Cell. 2012;151:1163–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hetz C, Chevet E, Harding HP. Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:703–719. doi: 10.1038/nrd3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villeneuve NF, Tian W, Wu T, Sun Z, Lau A, Chapman E, et al. USP15 negatively regulates Nrf2 through deubiquitination of Keap1. Mol Cell. 2013;51:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitnis NS, Pytel D, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Pant D, Zheng H, Maas NL, et al. miR-211 is a prosurvival microRNA that regulates Chop expression in a PERK-dependent manner. Mol Cell. 2012;48:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao RV, Hermel E, Castro-Obregon S, del Rio G, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, et al. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. Mechanism of caspase activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33869–33874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lépine S, Allegood JC, Park M, Dent P, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase-1 regulates ER stress-induced autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:350–361. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gewirtz DA. The four faces of autophagy: implications for cancer therapy. Can Res. 2014;74:647–651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamb CA, Yoshimori T, Tooze SA. The autophagosome: origins unknown, biogenesis complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:759–774. doi: 10.1038/nrm3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denoyelle C, Abou-Rjaily G, Bezrookove V, Verhaegen M, Johnson TM, Fullen DR, et al. Anti-oncogenic role of the endoplasmic reticulum differentially activated by mutations in the MAPK pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1053–1063. doi: 10.1038/ncb1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avivar-Valderas A, Wen HC, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Stress signaling and the shaping of the mammary tissue in development and cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:5483–5490. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart LS, Cunningham JT, Datta T, Dey S, Tameire F, Lehman SL, et al. ER stress-mediated autophagy promotes Myc-dependent transformation and tumor growth. J Clin Investig. 2012;122:4621–4634. doi: 10.1172/JCI62973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shajahan-Haq AN, Cook KL, Schwartz-Roberts JL, Eltayeb AE, Demas DM , Warri AM, et al. MYC regulates the unfolded protein response and glucose and glutamine uptake in endocrine resistant breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brünner N, Boulay V, Fojo A, Freter CE, Lippman ME, Clarke R. Acquisition of hormone-independent growth in MCF-7 cells is accompanied by increased expression of estrogen-regulated genes but without detectable DNA amplifications. Cancer Res. 1993;53:283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brünner N, Boysen B, Jirus S, Skaar TC, Holst-Hansen C, Lippman J, et al. MCF7/LCC9: an antiestrogen-resistant MCF-7 variant in which acquired resistance to the steroidal antiestrogen ICI 182,780 confers an early cross-resistance to the nonsteroidal antiestrogen tamoxifen. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3486–3493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler WB, Fontana JA. Responses to retinoic acid of tamoxifen-sensitive and—resistant sublines of human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6164–6167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boudreau HE, Broustas CG, Gokhale PC, Kumar D, Mewani RR, Rone JD, et al. Expression of BRCC3, a novel cell cycle regulated molecule, is associated with increased phospho-ERK and cell proliferation. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broustas CG, Ross JS, Yang Q, Sheehan CE, Riggins R, Noone AM, et al. The proapoptotic molecule BLID interacts with Bcl-XL and its downregulation in breast cancer correlates with poor disease-free and overall survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2939–2948. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broustas CG, Grammatikakis N, Eto M, Dent P, Brautigan DL, Kasid U. Phosphorylation of the myosin-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase by Raf-1 and inhibition of phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3053–3059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The National Center for Biotechnology Information Database (2015) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 22.The SIB Bioinformatics Resource Portal (2015) http://web.ExPASy.org. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 23.The UniProt Datasbase (2015) http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P57088. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 24.The PhosphoSitePlus Database (2015) http://www.phosphosite.org. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 25.The PSORT WWW-Server (2007) http://psort.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Accessed 26 July 2007

- 26.TOPO2 Transmembrane Protein Image Display Form (2015) http://www.sacs.ucsf.edu/cgi-bin/open-topo2.py. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 27.Phobius A Combined Transmembrane Topology and Signal Peptide Predictor (2015) http://www.phobius.sbc.su.se/cgi-bin/predict.pl. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 28.The cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (2015) http://www.cbioportal.org/cross_cancer.do?tab_index=tab_visualize&cancer_study_id=all&gene_list=TMEM33&data_priority=0&Action=Submit#crosscancer/overview/0/TMEM33. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 29.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez BP, Riggins RB, Shajahan AN, Klimach U, Wang A, Crawford AC, et al. Human X-box binding protein-1 confers both estrogen independence and antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer cell lines. FASEB J. 2007;21:4013–4027. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7990com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke R, Shajahan AN, Riggins RB, Cho Y, Crawford A, Xuan J, et al. Gene network signaling in hormone responsiveness modifies apoptosis and autophagy in breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke R, Cook KL, Hu R, Facey CO, Tavassoly I, Schwartz JL, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, the unfolded protein response, autophagy, and the integrated regulation of breast cancer cell fate. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1321–1331. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2012-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loi S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, Lallemand F, Tutt AM, Gillet C, et al. Definition of clinically distinct molecular subtypes in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas through genomic grade. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1239–1246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loi S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, Wirapati P, Lallemand F, Tutt AM, et al. Predicting prognosis using molecular profiling in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. BMC Genom. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loi S, Haibe-Kains B, Majjaj S, Lallemand F, Durbecq V, Larsimont D, et al. PIK3CA mutations associated with gene signature of low mTORC1 signaling and better outcomes in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10208–10213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907011107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, McGreevy M, Casey G, Cufer T, Paradiso A, et al. The 76-gene signature defines high-risk patients that benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:303–309. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigbolt KT, Prokhorova TA, Akimov V, Henningsen J, Johansen PT, Kratchmarova I, et al. System-wide temporal characterization of the proteome and phosphoproteome of human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Sci Signal. 2011;4:rs3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, et al. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell. 2011;44:325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner SA, Beli P, Weinert BT, Nielsen ML, Cox J, Mann M, et al. A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M111. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.STRING: Functional Protein Association Networks (2015) http://string905.embl.de/newstring_cgi/show_network_section.pl?taskId=ICWNuYf_Ewcx&interactive=no&advanced_menu=yes&network_flavor=evidence. Accessed 21 April 2015

- 42.Avivar-Valderas A, Salas E, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Nagi C, Debnath J, et al. PERK integrates autophagy and oxidative stress responses to promote survival during extracellular matrix detachment. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3616–3629. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05164-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (2015) http://www.blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi. Accessed 21 April 2015

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.